Biological Validation of Cortisol in Zebrafish Trunk, Skin Mucus, and Water as a Biomarker of Acute or Chronic Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Note

2.2. Animals and Housing

2.3. Experimental Set-Up

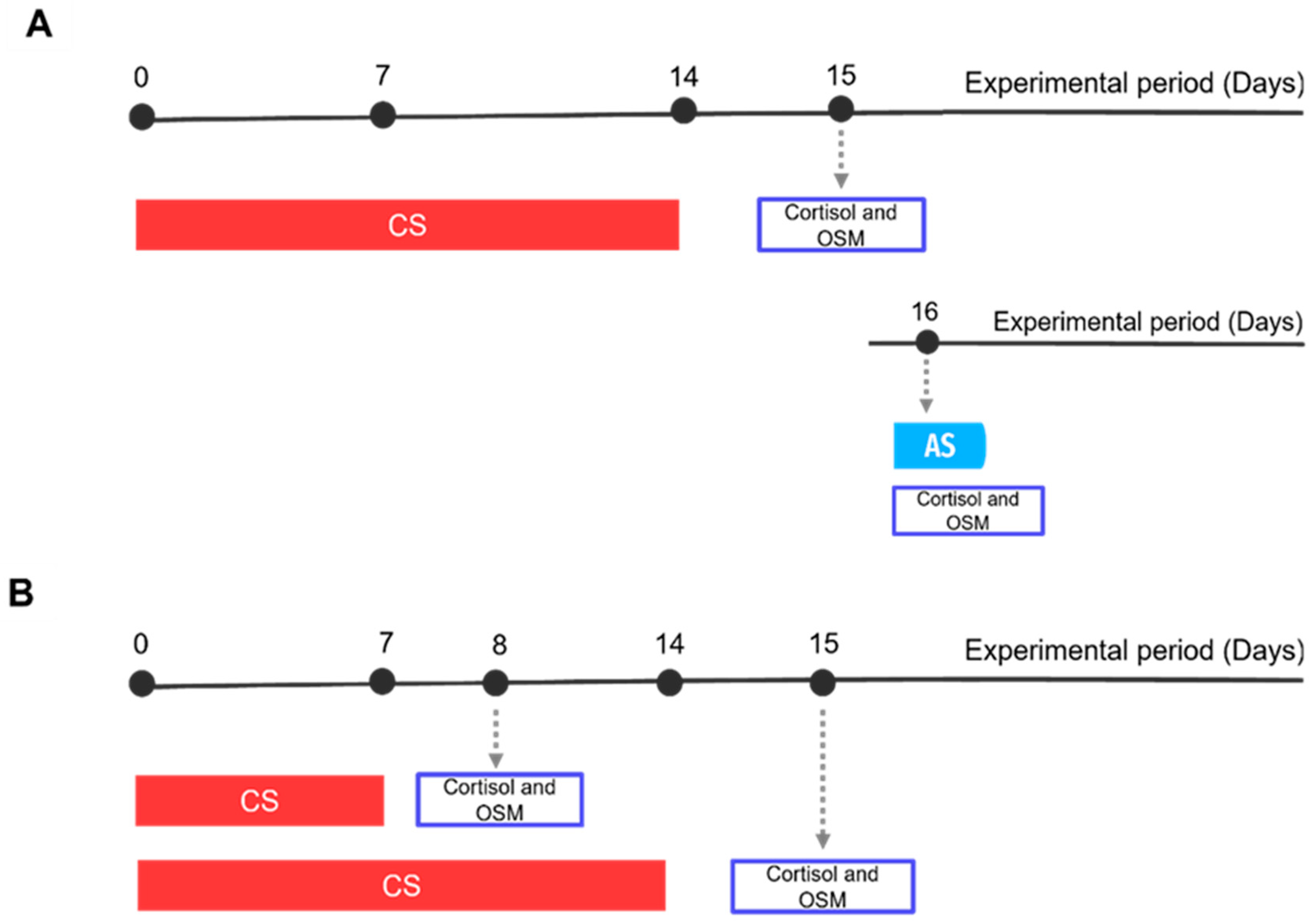

2.3.1. Experiment A: Biological Validation

2.3.2. Experiment B: Skin Mucus and Water Cortisol for Chronic Stress

2.4. Trunk and Skin Mucus Cortisol Analysis

2.5. Water Cortisol Analysis

2.6. Biochemical Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

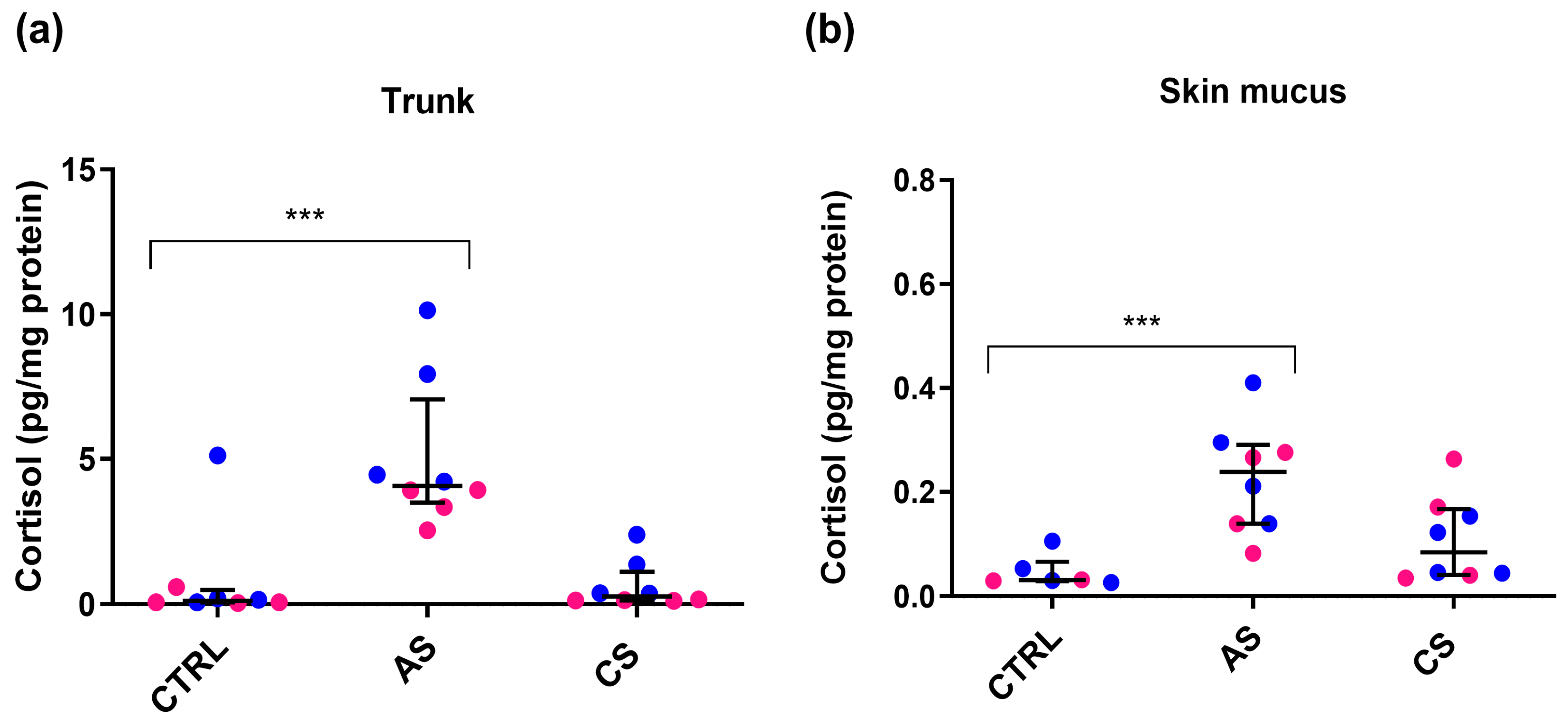

3.1. Experiment A: Cortisol

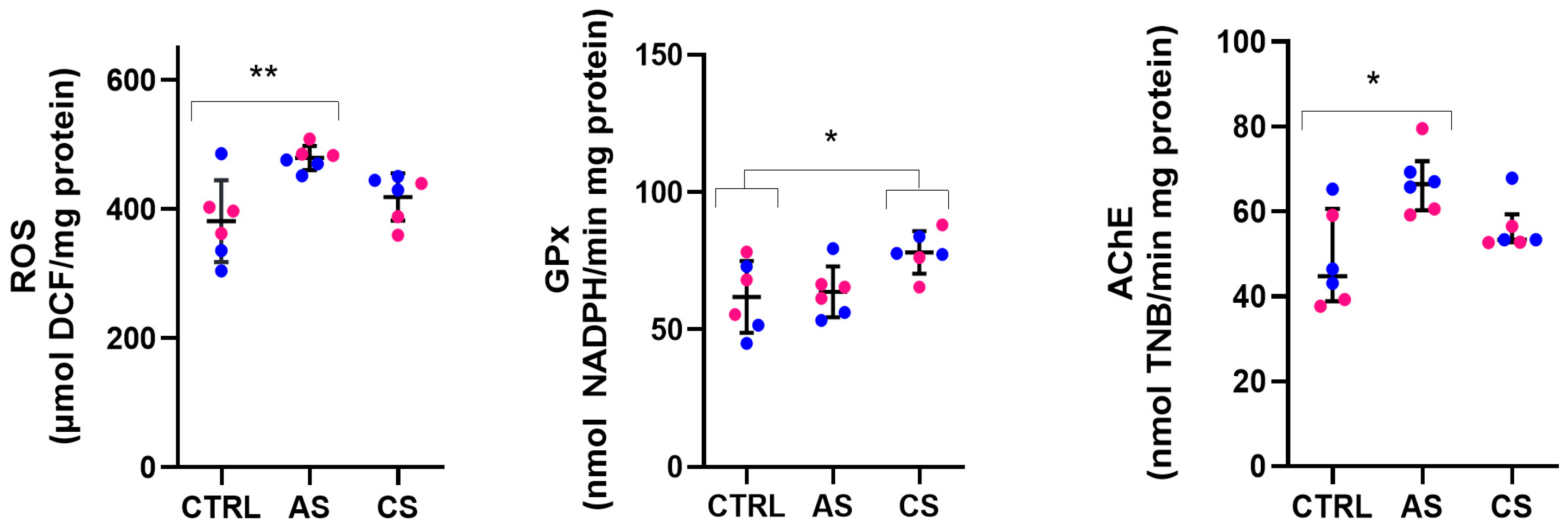

3.2. Experiment A: Oxidative Stress Markers

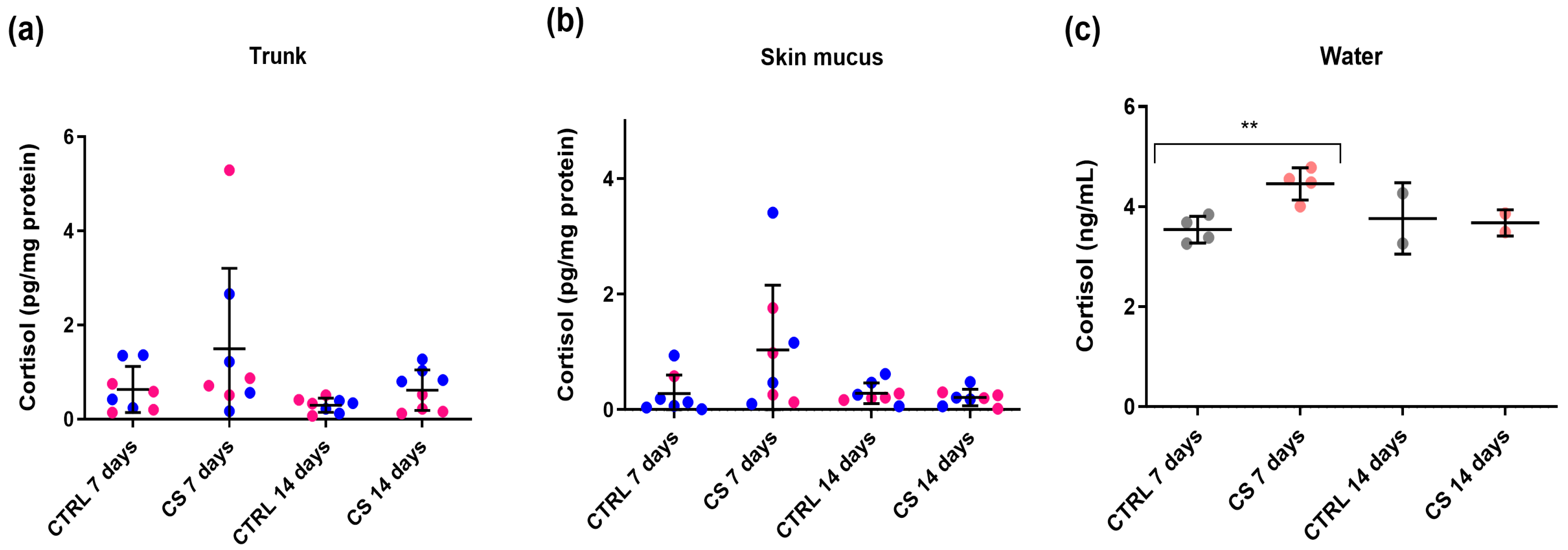

3.3. Experiment B: Cortisol

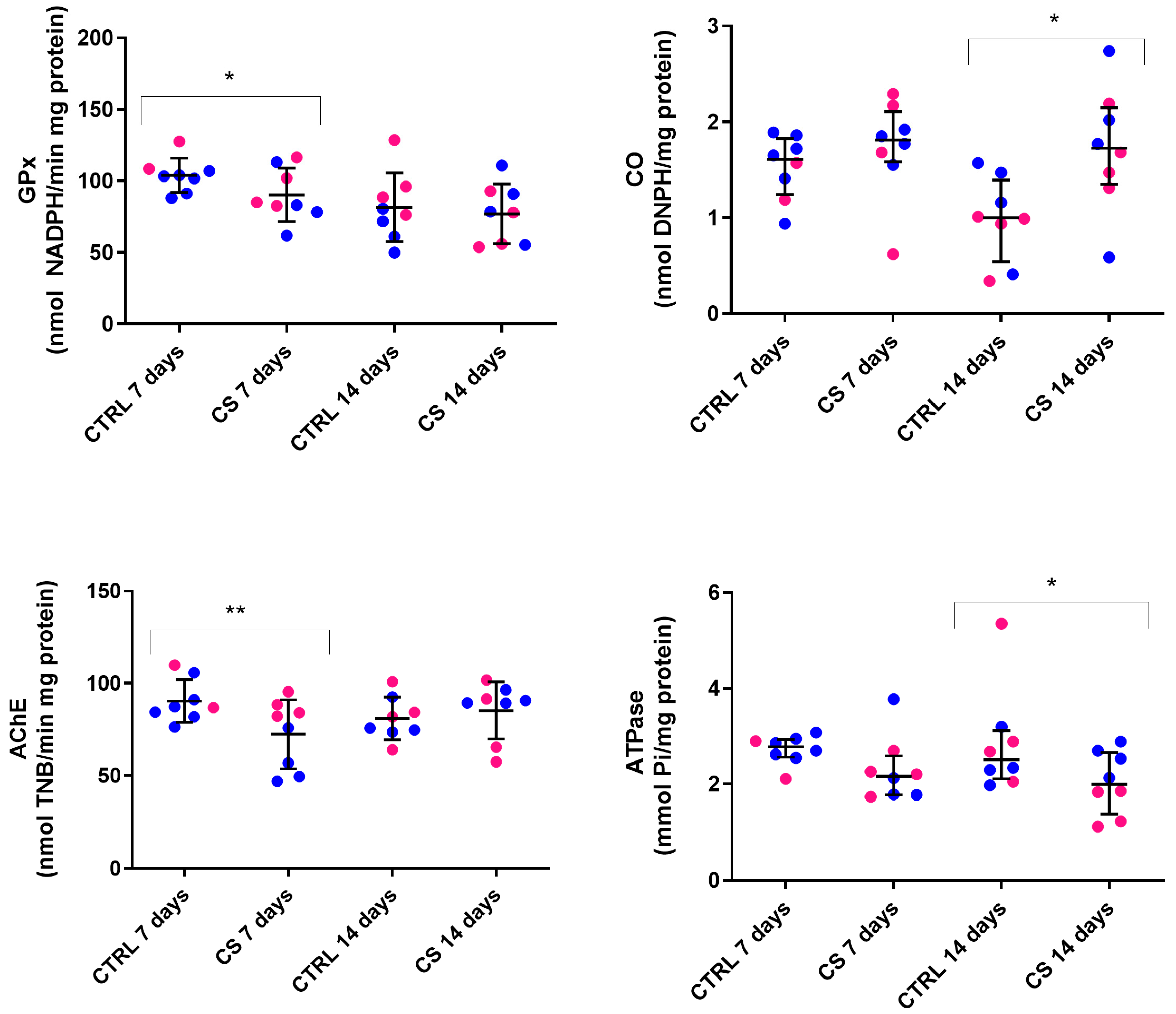

3.4. Experiment B: Oxidative Stress Markers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AE | Air exposure |

| AS | Acute stress |

| ATPase | Adenosine triphosphatase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CO | Carbonyls |

| CS | Chronic stress |

| CTRL | Control |

| DNAds | Double-stranded DNA |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| GSSG | Glutathione oxidized |

| GSH | Glutathione reduced |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| LD | Light/dark changes |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LW | Low water level |

| NBT | Nitroblue tetrazolium |

| NC | Net chasing |

| OSI | Oxidative stress index |

| OSM | Oxidative stress markers |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SI | Social isolation |

| SOD | Superoxidase dismutase |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TC | Tank change |

| TR | Tube restrain |

References

- Philippe, C.; Vergauwen, L.; Huyghe, K.; De Boeck, G.; Knapen, D. Chronic handling stress in zebrafish Danio rerio husbandry. J. Fish Biol. 2023, 103, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishis, S.; Tsang, B.; Ren, G.J.; Gerlai, R. Effects of different handling methods on the behavior of adult zebrafish. Physiol. Behav. 2023, 262, 114106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, M.; Digka, N.; Theodoridi, A.; Campo, A.; Barsakis, K.; Skouradakis, G.; Samaras, A.; Tsalafouta, A. Husbandry of zebrafish, Danio rerio, and the cortisol stress response. Zebrafish 2013, 10, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, J.M.; Feist, G.W.; Varga, Z.M.; Westerfield, M.; Kent, M.L.; Schreck, C.B. Whole-body cortisol is an indicator of crowding stress in adult zebrafish, Danio rerio. Aquaculture 2006, 258, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, Y.Y.; Parie, L.; Bakker, F.; Snelderwaard, P.; Tudorache, C.; Schaaf, M.; Slabbekoorn, H. Behavioral changes in response to sound exposure and no spatial avoidance of noisy conditions in captive zebrafish. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piato, Â.L.; Capiotti, K.M.; Tamborski, A.R.; Oses, J.P.; Barcellos, L.J.; Bogo, M.R.; Lara, D.R.; Vianna, M.R.; Bonan, C.D. Unpredictable chronic stress model in zebrafish (Danio rerio): Behavioral and physiological responses. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Shams, S.; Khan, A.; Gerlai, R. Early social deprivation does not affect cortisol response to acute and chronic stress in zebrafish. Stress 2021, 24, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoei, A.J. Evaluation of potential immunotoxic effects of iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) on antioxidant capacity, immune responses and tissue bioaccumulation in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 244, 109005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal, A.; Reyes-López, F.E.; Tallo-Parra, O.; Lopez-Bejar, M.; Tort, L. Comparative assessment of cortisol in plasma, skin mucus and scales as a measure of the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal axis activity in fish. Aquaculture 2019, 506, 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Alacid, L.; Sanahuja, I.; Ordóñez-Grande, B.; Sánchez-Nuño, S.; Herrera, M.; Ibarz, A. Skin mucus metabolites and cortisol in meagre fed acute stress-attenuating diets: Correlations between plasma and mucus. Aquaculture 2019, 499, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alacid, L.; Sanahuja, I.; Ordóñez-Grande, B.; Sánchez-Nuño, S.; Viscor, G.; Gisbert, E.; Herrera, M.; Ibarz, A. Skin mucus metabolites in response to physiological challenges: A valuable non-invasive method to study teleost marine species. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Montero, A.; Torrecillas, S.; Tort, L.; Ginés, R.; Acosta, F.; Izquierdo, M.; Montero, D. Stress response and skin mucus production of greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili) under different rearing conditions. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 735005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, F.A.; Cuesta, A.; Esteban, M.Á. Using skin mucus to evaluate stress in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 59, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parma, L.; Pelusio, N.F.; Gisbert, E.; Esteban, M.A.; D’Amico, F.; Soverini, M.; Candela, M.; Dondi, F.; Gatta, P.P.; Bonaldo, A. Effects of rearing density on growth, digestive conditions, welfare indicators and gut bacterial community of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata, L. 1758) fed different fishmeal and fish oil dietary levels. Aquaculture 2020, 518, 734854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fæste, C.; Tartor, H.; Moen, A.; Kristoffersen, A.; Dhanasiri, A.; Anonsen, J.; Furmanek, T.; Grove, S. Proteomic profiling of salmon skin mucus for the comparison of sampling methods. J. Chromatogr. B 2020, 1138, 121965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordelmondo, E.; Magi, G.E.; Friedl, A.; El-Matbouli, M.; Roncarati, A.; Saleh, M. Effects of stress conditions on plasma parameters and gene expression in the skin mucus of farmed rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1183246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, S.; Félix, L.; Costas, B.; Valentim, A.M. Housing conditions affect adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) behavior but not their physiological status. Animals 2023, 13, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartor, H.; Luis Monjane, A.; Grove, S. Quantification of defensive proteins in skin mucus of Atlantic salmon using minimally invasive sampling and high-sensitivity ELISA. Animals 2020, 10, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanahuja, I.; Guerreiro, P.M.; Girons, A.; Fernandez-Alacid, L.; Ibarz, A. Evaluating the repetitive mucus extraction effects on mucus biomarkers, mucous cells, and the skin-barrier status in a marine fish model. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1095246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertotto, D.; Poltronieri, C.; Negrato, E.; Majolini, D.; Radaelli, G.; Simontacchi, C. Alternative matrices for cortisol measurement in fish. Aquac. Res. 2010, 41, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez-Grande, B.; Guerreiro, P.M.; Sanahuja, I.; Fernández-Alacid, L.; Ibarz, A. Environmental salinity modifies mucus exudation and energy use in European sea bass juveniles. Animals 2021, 11, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Liu, B.-L.; Feng, W.-R.; Han, C.; Huang, B.; Lei, J.-L. Stress and immune responses in skin of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) under different stocking densities. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 55, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Brydges, N.M.; Boulcott, P.; Ellis, T.; Braithwaite, V.A. Quantifying stress responses induced by different handling methods in three species of fish. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 116, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caipang, C.M.A.; Fatira, E.; Lazado, C.C.; Pavlidis, M. Short-term handling stress affects the humoral immune responses of juvenile Atlantic cod, Gadus Morhua. Aquac. Int. 2014, 22, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.; López-Olmeda, J.; Garayzar, A.; Sánchez-Vázquez, F. Synchronization of daily rhythms of locomotor activity and plasma glucose, cortisol and thyroid hormones to feeding in Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) under a light–dark cycle. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 101, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto, A.; Peixoto, D.; Machado, M.; Costas, B.; Murta, D.; Valente, L.M. Physiological response of European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) juveniles to an acute stress challenge: The impact of partial and total Dietary Fishmeal replacement by an insect meal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fatima Pereira de Faria, C.; dos Reis Martinez, C.B.; Takahashi, L.S.; de Mello, M.M.M.; Martins, T.P.; Urbinati, E.C. Modulation of the innate immune response, antioxidant system and oxidative stress during acute and chronic stress in pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcon, M.; Mocelin, R.; Sachett, A.; Siebel, A.M.; Herrmann, A.P.; Piato, A. Enriched environment prevents oxidative stress in zebrafish submitted to unpredictable chronic stress. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Sert, N.P.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000411. [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield, M. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio), 4th ed.; University of Oregon Press: Eugene, OR, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis, M.; Theodoridi, A.; Tsalafouta, A. Neuroendocrine regulation of the stress response in adult zebrafish, Danio rerio. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, J.M.; Feist, G.W.; Varga, Z.M.; Westerfield, M.; Kent, M.L.; Schreck, C.B. Whole-body cortisol response of zebrafish to acute net handling stress. Aquaculture 2009, 297, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, S.; Félix, L.; Costas, B.; Valentim, A.M. Advancing cortisol measurements in zebrafish: Analytical validation of a commercial ELISA kit for skin mucus cortisol analysis. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H.; Higgins, M.; Marcato, M.; Galvin, P.; Teixeira, S.R. Immunosensor for assessing the welfare of trainee guide dogs. Biosensors 2021, 11, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Yu, L.; Liu, C.; Yu, K.; Shi, X.; Yeung, L.W.; Lam, P.K.; Wu, R.S.; Zhou, B. Hexabromocyclododecane-induced developmental toxicity and apoptosis in zebrafish embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2009, 93, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capriello, T.; Félix, L.M.; Monteiro, S.M.; Santos, D.; Cofone, R.; Ferrandino, I. Exposure to aluminium causes behavioural alterations and oxidative stress in the brain of adult zebrafish. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 85, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, L.; Carreira, P.; Peixoto, F. Effects of chronic exposure of naturally weathered microplastics on oxidative stress level, behaviour, and mitochondrial function of adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136895. [Google Scholar]

- Wallin, B.; Rosengren, B.; Shertzer, H.G.; Camejo, G. Lipoprotein oxidation and measurement of thiobarbituric acid reacting substances formation in a single microtiter plate: Its use for evaluation of antioxidants. Anal. Biochem. 1993, 208, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, C.S.; Oliveira, R.; Bento, F.; Geraldo, D.; Rodrigues, J.V.; Marcos, J.C. Simplified 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine spectrophotometric assay for quantification of carbonyls in oxidized proteins. Anal. Biochem. 2014, 458, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Olive, P.L. DNA precipitation assay: A rapid and simple method for detecting DNA damage in mammalian cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1988, 11, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lança, M.J.; Machado, M.; Ferreira, A.F.; Quintella, B.R.; de Almeida, P.R. Structural lipid changes and Na+/K+-ATPase activity of gill cells’ basolateral membranes during saltwater acclimation in sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus, L.) juveniles. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 189, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V., Jr.; Featherstone, R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, I.; Oliveira, R.; Lourenço, J.; Grisolia, C.K.; Mendo, S.; Soares, A. Biomarkers as a tool to assess effects of chromium (VI): Comparison of responses in zebrafish early life stages and adults. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 152, 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Balmuș, I.-M.; Lefter, R.M.; Robea, M.-A.; Lungu, F.; Săvucă, A.; Ciobîcă, A.; Gorgan, L.; Hurjui, I.A.; Nicușor, M. Study on some behavioral and oxidative changes observed in zebrafish exposed to chronic stress. Bull. Integr. Psychiatry 2024, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Saikia, S.K. Use of zebrafish as a model organism to study oxidative stress: A review. Zebrafish 2022, 19, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Santo, G.; Conterato, G.M.; Barcellos, L.J.; Rosemberg, D.B.; Piato, A.L. Acute restraint stress induces an imbalance in the oxidative status of the zebrafish brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 558, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Félix, A.S.; Faustino, A.I.; Cabral, E.M.; Oliveira, R.F. Noninvasive measurement of steroid hormones in zebrafish holding-water. Zebrafish 2013, 10, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midttun, H.; Øverli, Ø.; Tudorache, C.; Mayer, I.; Johansen, I. Non-invasive sampling of water-borne hormones demonstrates individual consistency of the cortisol response to stress in laboratory zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mercado, E.; Larrán, A.M.; Pinedo, J.; Tomás-Almenar, C. Skin mucous: A new approach to assess stress in rainbow trout. Aquaculture 2018, 484, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Martinez, L.; Brandts, I.; Reyes-López, F.; Tort, L.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Teles, M. Skin mucus as a relevant low-invasive biological matrix for the measurement of an acute stress response in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Water 2022, 14, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsos, I.; Kotzamanis, Y.; Henry, M.; Angelidis, P.; Alexis, M. Monitoring stress in fish by applying image analysis to their skin mucous cells. Eur. J. Histochem. EJH 2010, 54, e22. [Google Scholar]

- Madaro, A.; Nilsson, J.; Whatmore, P.; Roh, H.; Grove, S.; Stien, L.H.; Olsen, R.E. Acute stress response on Atlantic salmon: A time-course study of the effects on plasma metabolites, mucus cortisol levels, and head kidney transcriptome profile. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 49, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.-h.; Fu, C.; Tan, X.-t.; Fu, S.-j. Responses of zebrafish to chronic environmental stressors: Anxiety-like behavior and its persistence. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1551595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, A.P.; Mourad, M.M.; Power, D.M. Skin damage caused by scale loss modifies the intestine of chronically stressed gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata, L.). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 118, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.M.; Brinchmann, M.F.; Hanssen, A.; Iversen, M.H. Changes in the skin proteome and signs of allostatic overload type 2, chronic stress, in response to repeated overcrowding of lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus L.). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 891451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopinka, N.M.; Donaldson, M.R.; O’Connor, C.M.; Suski, C.D.; Cooke, S.J. Stress Indicators in Fish. In Fish Physiology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 405–462. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, C.L.; Mocelin, R.; Marcon, M.; Villanova, D.; Koakoski, G.; de Abreu, M.S.; Oliveira, T.A.; Barcellos, L.J.; Piato, A.L.; Bonan, C.D. Gender differences in aggression and cortisol levels in zebrafish subjected to unpredictable chronic stress. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 171, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faught, E.; Aluru, N.; Vijayan, M.M. The molecular stress response. In Fish Physiology; Elsevier Inc.: London, UK, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 113–166. [Google Scholar]

- Marcon, M.; Mocelin, R.; Benvenutti, R.; Costa, T.; Herrmann, A.P.; de Oliveira, D.L.; Koakoski, G.; Barcellos, L.J.; Piato, A. Environmental enrichment modulates the response to chronic stress in zebrafish. J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 221, jeb176735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, L.S.; Angarica, L.M.; Hauser-Davis, R.A.; Quinete, N. Cortisol as a stress indicator in fish: Sampling methods, analytical techniques, and organic pollutant exposure assessments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6237. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, T.; Sanders, M.; Scott, A. Non-invasive monitoring of steroids in fishes. Vet. Med. Austria 2013, 100, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ruane, N.M.; Komen, H. Measuring cortisol in the water as an indicator of stress caused by increased loading density in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Aquaculture 2003, 218, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, H.N.; Said, U.Z.; Mahdy, E.M.; Elmezayen, H.E.; Shedid, S.M. Fish oil omega-3 fatty acids reduce the severity of radiation-induced oxidative stress in the rat brain. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2014, 90, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Santa Lopes, T.; Costas, B.; Ramos-Pinto, L.; Reynolds, P.; Imsland, A.K.; Fernandes, J.M. Exploring the effects of acute stress exposure on lumpfish plasma and liver biomarkers. Animals 2023, 13, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzian, J.; Fontana, B.D.; Quadros, V.A.; Rosemberg, D.B. Conspecific alarm substance differently alters group behavior of zebrafish populations: Putative involvement of cholinergic and purinergic signaling in anxiety-and fear-like responses. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 320, 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Kapoor, K.; Sayeepriyadarshini, A.; Dikshit, M.; Palit, G.; Nath, C. Immobilization stress-induced changes in brain acetylcholinesterase activity and cognitive function in mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2000, 42, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, L.K.; Sahoo, P.K.; Chauhan, N.R.; Das, S.K. Temporal exposure to chronic unpredictable stress induces precocious neurobehavioral deficits by distorting neuromorphology and glutathione biosynthesis in zebrafish brain. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 418, 113672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedara, I.A.; Souza, T.P.; Canzian, J.; Olabiyi, A.A.; Borba, J.V.; Biasuz, E.; Sabadin, G.R.; Goncalves, F.L.; Costa, F.V.; Schetinger, M.R. Induction of aggression and anxiety-like responses by perfluorooctanoic acid is accompanied by modulation of cholinergic-and purinergic signaling-related parameters in adult zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113635. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Aceves, L.M.; Pérez-Alvarez, I.; Onofre-Camarena, D.B.; Gutiérrez-Noya, V.M.; Rosales-Pérez, K.E.; Orozco-Hernández, J.M.; Hernández-Navarro, M.D.; Flores, H.I.; Gómez-Olivan, L.M. Prolonged exposure to the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone induces brain damage via oxidative stress and apoptotic response in adult Danio rerio. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomini, A.C.; Bueno, B.W.; Marcon, L.; Scolari, N.; Genario, R.; Demin, K.A.; Kolesnikova, T.O.; Kalueff, A.V.; de Abreu, M.S. An acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, donepezil, increases anxiety and cortisol levels in adult zebrafish. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, G.L.; Subhashree, K.D.; Lite, C.; Santosh, W.; Barathi, S. Transient exposure of methylparaben to zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos altered cortisol level, acetylcholinesterase activity and induced anxiety-like behaviour. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2019, 279, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, T.O.; Prokhorenko, N.O.; Amikishiev, S.V.; Nikitin, V.S.; Shevlyakov, A.D.; Ikrin, A.N.; Mukhamadeev, R.R.; Buglinina, A.D.; Apukhtin, K.V.; Moskalenko, A.M. Differential effects of chronic unpredictable stress on behavioral and molecular (cortisol and microglia-related neurotranscriptomic) responses in adult leopard (leo) zebrafish. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 51, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jorge, S.; Félix, L.; Costas, B.; Ramos-Pinto, L.; Teixeira, S.R.; Valentim, A.M. Biological Validation of Cortisol in Zebrafish Trunk, Skin Mucus, and Water as a Biomarker of Acute or Chronic Stress. Fishes 2026, 11, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010066

Jorge S, Félix L, Costas B, Ramos-Pinto L, Teixeira SR, Valentim AM. Biological Validation of Cortisol in Zebrafish Trunk, Skin Mucus, and Water as a Biomarker of Acute or Chronic Stress. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleJorge, Sara, Luís Félix, Benjamín Costas, Lourenço Ramos-Pinto, Sofia R. Teixeira, and Ana M. Valentim. 2026. "Biological Validation of Cortisol in Zebrafish Trunk, Skin Mucus, and Water as a Biomarker of Acute or Chronic Stress" Fishes 11, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010066

APA StyleJorge, S., Félix, L., Costas, B., Ramos-Pinto, L., Teixeira, S. R., & Valentim, A. M. (2026). Biological Validation of Cortisol in Zebrafish Trunk, Skin Mucus, and Water as a Biomarker of Acute or Chronic Stress. Fishes, 11(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010066