Fertilization Effects on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Budgets in Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) Pond Grow-Out Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pond Water Quality

2.2. Harvest

2.3. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Budget

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boyd, C.E.; D’Abramo, L.R.; Glencross, B.D.; Huyben, D.C.; Juarez, L.M.; Lockwood, G.S.; McNevin, A.A.; Tacon, A.G.J.; Teletchea, F.; Tomasso, J.R.; et al. Achieving Sustainable Aquaculture: Historical and Current Perspectives and Future Needs and Challenges. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 578–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flickinger, D.L.; Dantas, D.P.; Proença, D.C.; David, F.S.; Valenti, W.C. Phosphorus in the Culture of the Amazon River Prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum) and Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) Farmed in Monoculture and in Integrated Multitrophic Systems. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 1002–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flickinger, D.L.; Costa, G.A.; Dantas, D.P.; Moraes-Valenti, P.; Valenti, W.C. The Budget of Nitrogen in the Grow-out of the Amazon River Prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum Heller) and Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum Cuvier) Farmed in Monoculture and in Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture Systems. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 3444–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, F.S.; Proença, D.C.; Valenti, W.C. Nitrogen Budget in Integrated Aquaculture Systems with Nile Tilapia and Amazon River Prawn. Aquac. Int. 2017, 25, 1733–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, F.S.; Proença, D.C.; Valenti, W.C. Phosphorus Budget in Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture Systems with Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, and Amazon River Prawn, Macrobrachium amazonicum. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2017, 48, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Zou, T.; Lassaletta, L.; Quan, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, W. Quantifying Nutrient Budgets for Sustainable Nutrient Management. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2020, 34, e2018GB006060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Sahu, B.C.; Mahapatra, A.S.; Dey, L. Nutrient Budgets and Effluent Characteristics in Giant Freshwater Prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) Culture Ponds. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 92, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcios, A.E.; Papenbrock, J. Sustainable Treatment of Aquaculture Effluents-What Can We Learn from the Past for the Future? Sustainability 2014, 6, 836–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E. Comparison of 5 Fertilization Programs for Fish Ponds. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1981, 110, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knud-Hansen, C.F.; Batterson, T.R.; McNabb, C.D.; Harahat, I.S.; Sumantadinata, K.; Eidman, H.M. Nitrogen Input, Primary Productivity and Fish Yield in Fertilized Freshwater Ponds in Indonesia. Aquaculture 1991, 94, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.K.; Bhatnagar, A. Effect of Fertilization Frequency on Pond Productivity and Fish Biomass in Still Water Ponds Stocked with Cirrhinus mrigala (Ham.). Aquac. Res. 2000, 31, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.K.; Bhatnagar, A. Effect of Different Doses of Organic Fertilizer (Cow Dung) on Pond Productivity and Fish Biomass in Stillwater Ponds. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 1999, 15, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.C.; Adhikari, S.; Mahapatra, A.S.; Dey, L. Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Carbon Budgets in Polyculture Ponds of Indian Major Carps and Giant Freshwater Prawn in Orissa State, India. J. Appl. Aquac. 2015, 27, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.C.; Adhikari, S.; Mahapatra, A.S.; Dey, L. Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Budget in Scampi (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) Culture Ponds. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 10157–10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, D.P.; Lin, C.K. Water Quality and Nutrient Budget in Closed Shrimp (Penaeus monodon) Culture Systems. Aquac. Eng. 2003, 27, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duodu, C.; Boateng, D.; Edziyie, R. Effect of Pond Fertilization on Productivity of Tilapia Pond Culture in Ghana. J. Fish. Coast. Manag. 2020, 2, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.C.; Silva, C.R. Impact of Pond Management on Tambaqui, Colossoma macropomum (Cuvier), Production during Growth-out Phase. Aquac. Res. 2009, 40, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.D.; Gomes, L.C.; Roubach, R. Growth, Yield, Water and Effluent Quality in Ponds with Different Management during Tambaqui Juvenile Production. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2007, 42, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouil, S.; Samsudin, R.; Slembrouck, J.; Sihabuddin, A.; Sundari, G.; Khazaidan, K.; Kristanto, A.H.; Pantjara, B.; Caruso, D. Nutrient Budgets in a Small-Scale Freshwater Fish Pond System in Indonesia. Aquaculture 2019, 504, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixe BR (Associação Brasileira da Piscicultura). Anuário Peixe BR da Piscicultura 2025: Mapa da Piscicultura No Brasil; Associação Brasileira da Piscicultura—Peixe BR: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Valenti, W.C.; Barros, H.P.; Moraes-Valenti, P.; Bueno, G.W.; Cavalli, R.O. Aquaculture in Brazil: Past, Present and Future. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 19, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilsdorf, A.W.S.; Hallerman, E.; Valladão, G.M.R.; Zaminhan-Hassemer, M.; Hashimoto, D.T.; Dairiki, J.K.; Takahashi, L.S.; Albergaria, F.C.; Gomes, M.E.d.S.; Venturieri, R.L.L.; et al. The Farming and Husbandry of Colossoma macropomum: From Amazonian Waters to Sustainable Production. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 993–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woynárovich, A.; Van Anrooy, R. Field Guide to the Culture of Tambaqui Colossoma macropomum, Cuvier, 1816; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019; Volume 624 de FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper; ISBN 978-92-5-131242-1. [Google Scholar]

- Valladão, G.M.R.; Gallani, S.U.; Pilarski, F. South American Fish for Continental Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.F.; dos Reis, A.G.P.; Costa, V.E.; Valenti, W.C. Natural Food Intake and Its Contribution to Tambaqui Growth in Fertilized and Unfertilized Ponds. Fishes 2024, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, J.A.S.; Moraes, M.A.B.; Carmo, C.F.; Mercante, C.T.J. Fluxo de Nitrogênio e Fósforo Na Produção de Tilápia-Do-Nilo (Oreochromis Niloticus) a Partir Da Aplicação de Indicadores Ambientais. Braz. J. Biol. 2018, 78, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.C.B.; Miranda, E.C.; Correia, R. Exigências Nutricionais e Alimentação Do Tambaqui. In Nutriaqua: Nutrição e Alimentação de Especies de Interesse Para a Aquicultura Brasileira; Fracalossi, D., Cyrino, J.E.P., Eds.; Sociedade Brasileira de Aquicultura e Biologia Aquática: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2013; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Waste Water, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.F.; Maciel-Honda, P.O. Implications of Pond Fertilization on Fish Performance, Health, Effluent, and Sediment Quality in Tambaqui Aquaculture. Aquat. Living Resour. 2025, 38, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E. Water Quality: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; ISBN 9783030233341. [Google Scholar]

- INMET—Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia Mapa de Estações Meteorológicas e Dados Pluviométricos. Available online: https://mapas.inmet.gov.br/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists). Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, C.E.; Lichtkoppler, F. Water Quality Management in Pond Fish Culture (Research and Development Series), 1st ed.; Boyd, C.E., Lichtkoppler, F., Eds.; Auburn University: Auburn, AL, USA, 1979; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- van Raij, B.; Cantarella, H.; Quaggio, J.A.; Andrade, J.C. Análise Química Para Avaliação Da Fertilidade de Solos Tropicais; Instituto Agronômico: Campinas, Brazil, 2001; ISBN 85-85564-05-9. [Google Scholar]

- Munsiri, P.; Boyd, C.E.; Hajek, B.F. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Bottom Soil Profiles in Ponds at Auburn, Alabama, USA and a Proposed System for Describing Pond Soil Horizons. J. World Aquac. Soc. 1995, 26, 346–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Cox, D.R. An Analysis of Transformation. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1964, 26, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Belmudes, D.; Boaratti, A.Z.; Mantoan, P.V.L.; Marques, A.M.; Ferreira, J.R.C.; Moraes-Valenti, P.; Flickinger, D.L.; Valenti, W.C. Nitrogen Budget in Yellow-Tail Lambari Monoculture and Integrated Aquaculture. Fishes 2025, 10, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhan, D.K.; Verdegem, M.C.J.; Milstein, A.; Verreth, J.A.V. Water and Nutrient Budgets of Ponds in Integrated Agriculture-Aquaculture Systems in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Aquac. Res. 2008, 39, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pedologia Do Estado Do Tocantins. Available online: https://geoftp.ibge.gov.br/informacoes_ambientais/pedologia/mapas/unidades_da_federacao/to_pedologia.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Campos, D.S.d.; Brizzi, R.R.; Almeida, R.E.M.; Vidal-Torrado, P. Plintossolos Pétricos Do Tocantins. In Compêndio de Solos do Brasil; Fontana, A., Loss, A., Pedron, F.d.A., Eds.; Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo: Santa Maria, CA, USA, 2025; Volume 2, pp. 146–170. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, S.; Gustafson, A.; Joelsson, A.; Pansar, J.; Stibe, L. Nitrogen Removal in Created Ponds. Ambio 1994, 23, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Joyni, M.J.; Kurup, B.M.; Avnimelech, Y. Bioturbation as a Possible Means for Increasing Production and Improving Pond Soil Characteristics in Shrimp-Fish Brackish Water Ponds. Aquaculture 2011, 318, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Junior, E.S.; Temmink, R.J.M.; Buhler, B.F.; Souza, R.M.; Resende, N.; Spanings, T.; Muniz, C.C.; Lamers, L.P.M.; Kosten, S. Benthivorous Fish Bioturbation Reduces Methane Emissions, but Increases Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Freshw. Biol. 2019, 64, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E. Guidelines for Aquaculture Effluent Management at the Farm-Level. Aquaculture 2003, 226, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.F.; Aubin, J.; Valenti, W.C. Reducing Environmental Impacts in Tambaqui Aquaculture: A Life Cycle Assessment of Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture with Curimba. Aquaculture 2026, 612, 743144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacout, D.M.M.; Soliman, N.F.; Yacout, M.M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Tilapia in Two Production Systems: Semi-Intensive and Intensive. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, G.F. Characteristics of Denitrification and Anammox in the Sediment of an Aquaculture Pond. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1023835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.P.D.; Kosten, S.; Muniz, C.C.; Oliveira-Junior, E.S. From Feed to Fish—Nutrients’ Fate in Aquaculture Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fish Weight (g) | Crude Protein (%) | Pellet Size (mm) | Feed Rate (% Body Weight Day−1) | Number of Daily Meals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–200 | 32 | 4 | 4.5 | 2 |

| 200–500 | 32 | 6 | 3.5 | 2 |

| 500–700 | 32 | 6 | 2.5 | 2 |

| 700– | 28 | 10 | 2.5 | 2 |

| Water Parameters | Fert | NoFert | p-Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treat | Time | Treat × Time | |||

| Total Nitrogen (mg L−1) | 5.72 ± 2.99 | 5.83 ± 3.32 | 0.9481 | <0.0001 | 0.0241 |

| Total Phosphorus (µg L−1) | 390 ± 230 a | 330 ± 220 b | 0.0424 | 0.0001 | 0.7673 |

| Chlorophyll-a (µg L−1) | 17.06 ± 16.48 a | 10.71 ± 8.29 b | 0.0023 | 0.0001 | 0.0396 |

| Ecological Compartments | Nitrogen (kg ha−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fert | NoFert | p-Value | |

| TNin | |||

| Commercial diet | 700 ± 25 b | 752 ± 12 a | 0.010 |

| Inlet water (fill ponds) | 0.07 | 0.07 | - |

| Inlet water (renovation) | 732 | 732 | - |

| Stocked fish | 14 | 14 | - |

| Fertilizers | 349 | - | - |

| Total inputs | 1795 ± 25 a | 1498 ± 12 b | <0.001 |

| TNout | |||

| Outlet water (drain pond) | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.705 |

| Outlet water (renovation) | 742 ± 141 | 826 ± 67 | 0.323 |

| Harvested fish | 301 ± 34 | 296 ± 19 | 0.809 |

| Sediment | −104 ± 712 | 378 ± 643 | 0.353 |

| Total outputs | 938 ± 632 | 1500 ± 684 | 0.273 |

| UN | |||

| Inputs–Outputs | 857 ± 620 | −2 ± 680 | 0.146 |

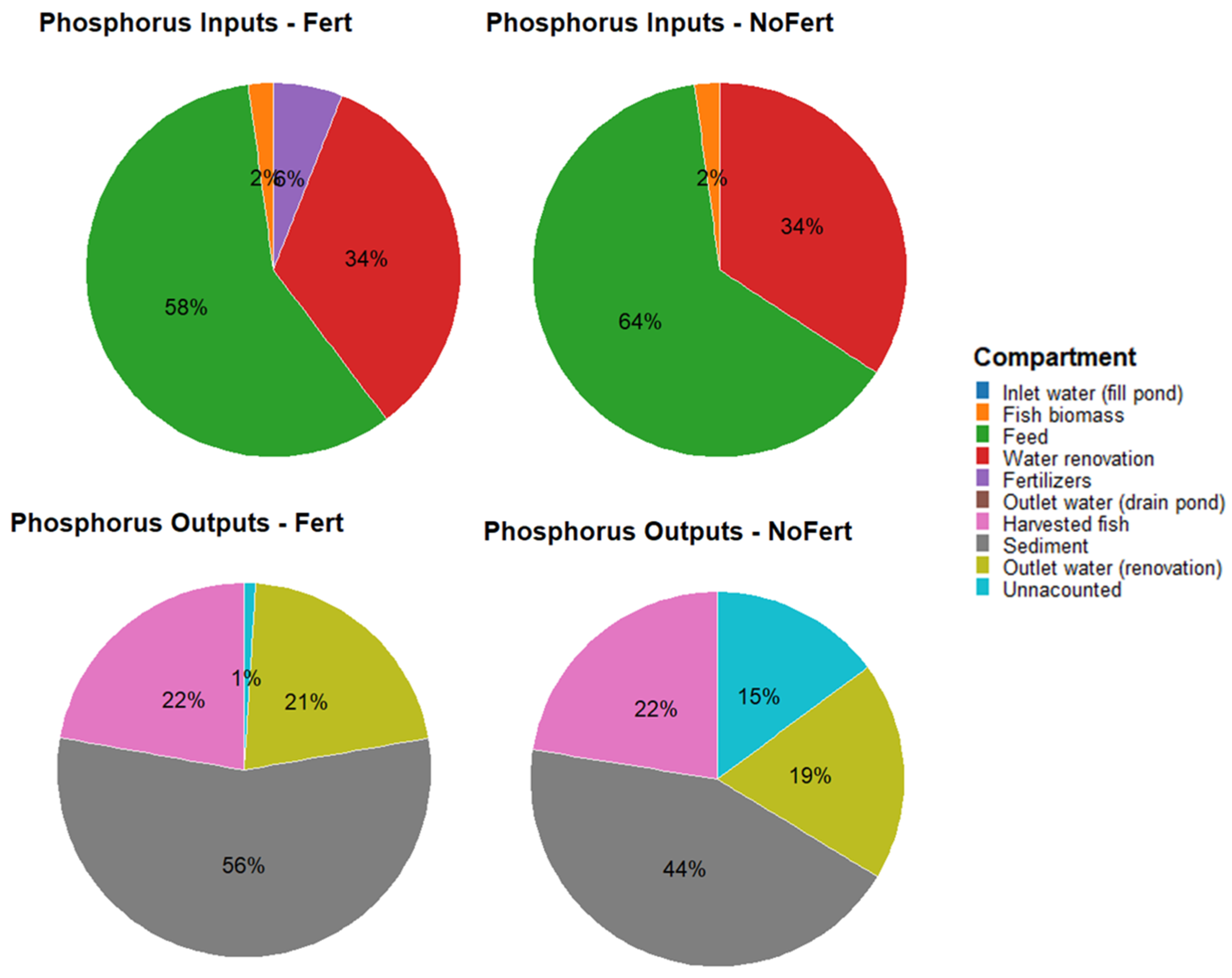

| Ecological Compartments | Phosphorus (kg ha−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fert | NoFert | p-Value | |

| TPin | |||

| Commercial diet | 144 ± 6 b | 156 ± 5 a | 0.027 |

| Inlet water (fill ponds) | 0.003 | 0.003 | - |

| Inlet water (renovation) | 52 | 52 | - |

| Stocked fish | 5 | 5 | - |

| Fertilizers | 15 | - | - |

| Total inputs | 248 ± 6 | 245 ± 5 | 0.350 |

| TPout | |||

| Outlet water (drain pond) | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.474 |

| Outlet water (renovation) | 53 ± 11 | 46 ± 5 | 0.282 |

| Harvested fish | 56 ± 6 | 55 ± 3 | 0.860 |

| Sediment | 143 ± 105 | 107 ± 79 | 0.847 |

| Total outputs | 252 ± 108 | 208 ± 79 | 0.340 |

| UN | |||

| Inputs–Outputs | −4 ± 113 | 36 ± 75 | 0.534 |

| Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fert | NoFert | p-Value | |

| Feed nitrogen conversion—FNC (%) | 43 ± 4 | 40 ± 3 | 0.3271 |

| Total nitrogen use efficiency—NUE (%) | 17 ± 2 b | 20 ± 1 a | 0.0272 |

| Feed phosphorus conversion—FPC (%) | 38 ± 4 | 35 ± 2 | 0.2043 |

| Total phosphorus use efficiency—PUE (%) | 26 ± 3 | 26 ± 1 | 0.9214 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lima, A.F.; Valenti, W.C. Fertilization Effects on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Budgets in Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) Pond Grow-Out Systems. Fishes 2026, 11, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010005

Lima AF, Valenti WC. Fertilization Effects on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Budgets in Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) Pond Grow-Out Systems. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Adriana Ferreira, and Wagner Cotroni Valenti. 2026. "Fertilization Effects on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Budgets in Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) Pond Grow-Out Systems" Fishes 11, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010005

APA StyleLima, A. F., & Valenti, W. C. (2026). Fertilization Effects on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Budgets in Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) Pond Grow-Out Systems. Fishes, 11(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010005