Investigation of SNPs at NKCC Gene of Scylla paramamosain to Unveil the Low-Salinity Tolerance Phenotype

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. DNA and RNA Extraction

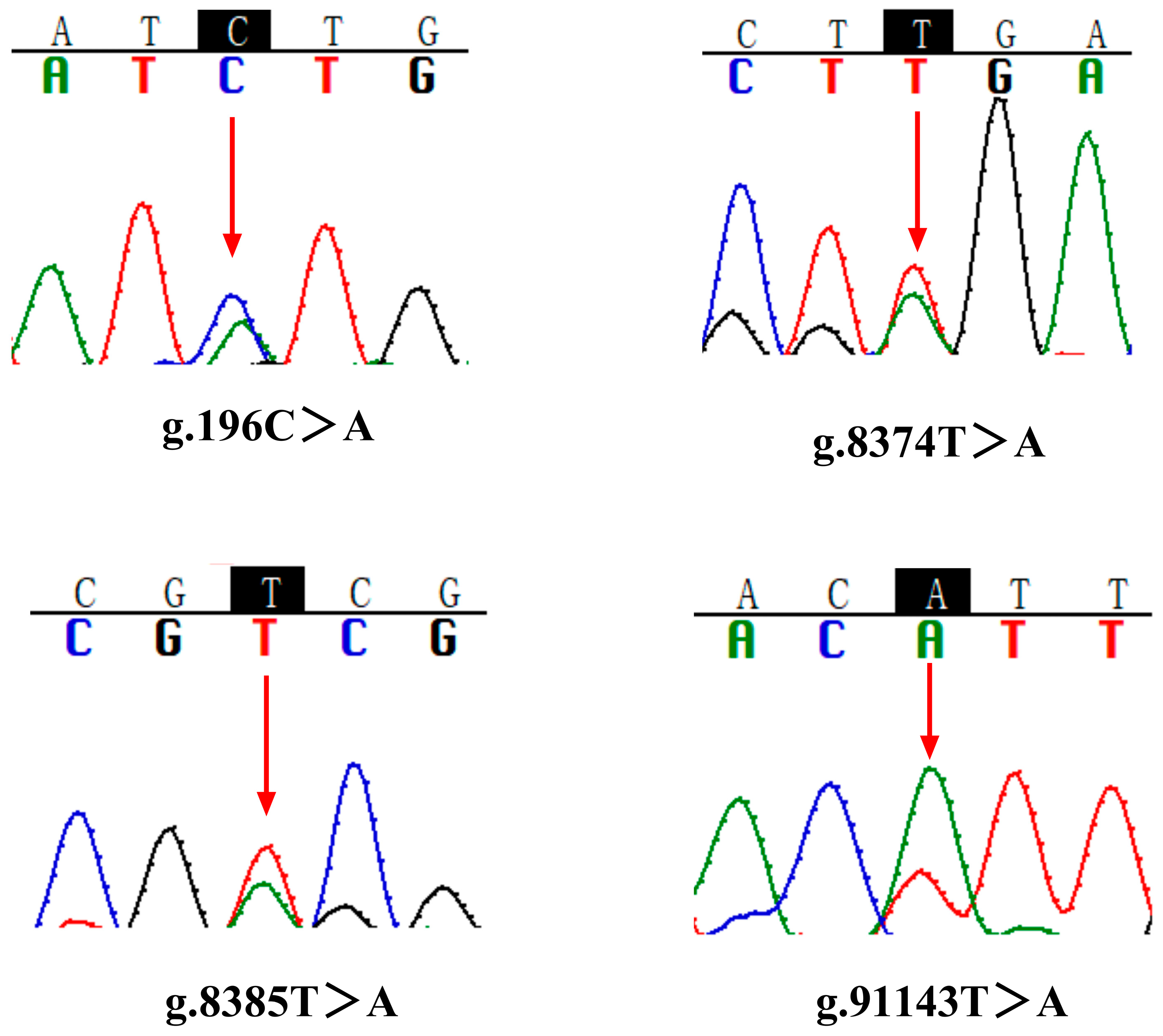

2.2.2. SNP Screening and Genotyping

2.2.3. Quantitative Expression Analysis of Different Genotypes at Mutation Sites

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. NKCC Gene Structure and SNPs Screening

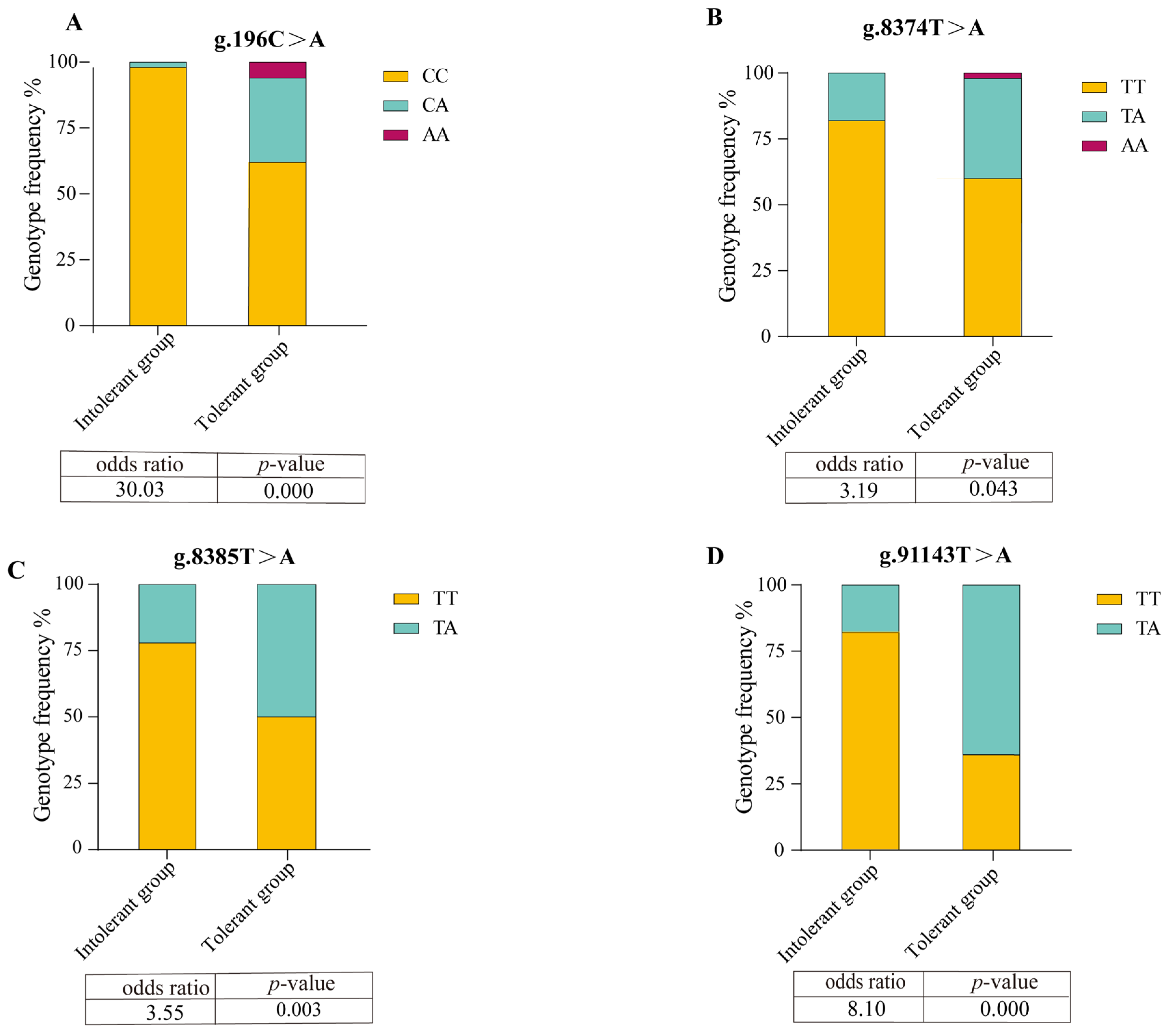

3.2. Association Analysis Between SNP Loci of NKCC Gene and Phenotype of Low-Salinity Tolerance

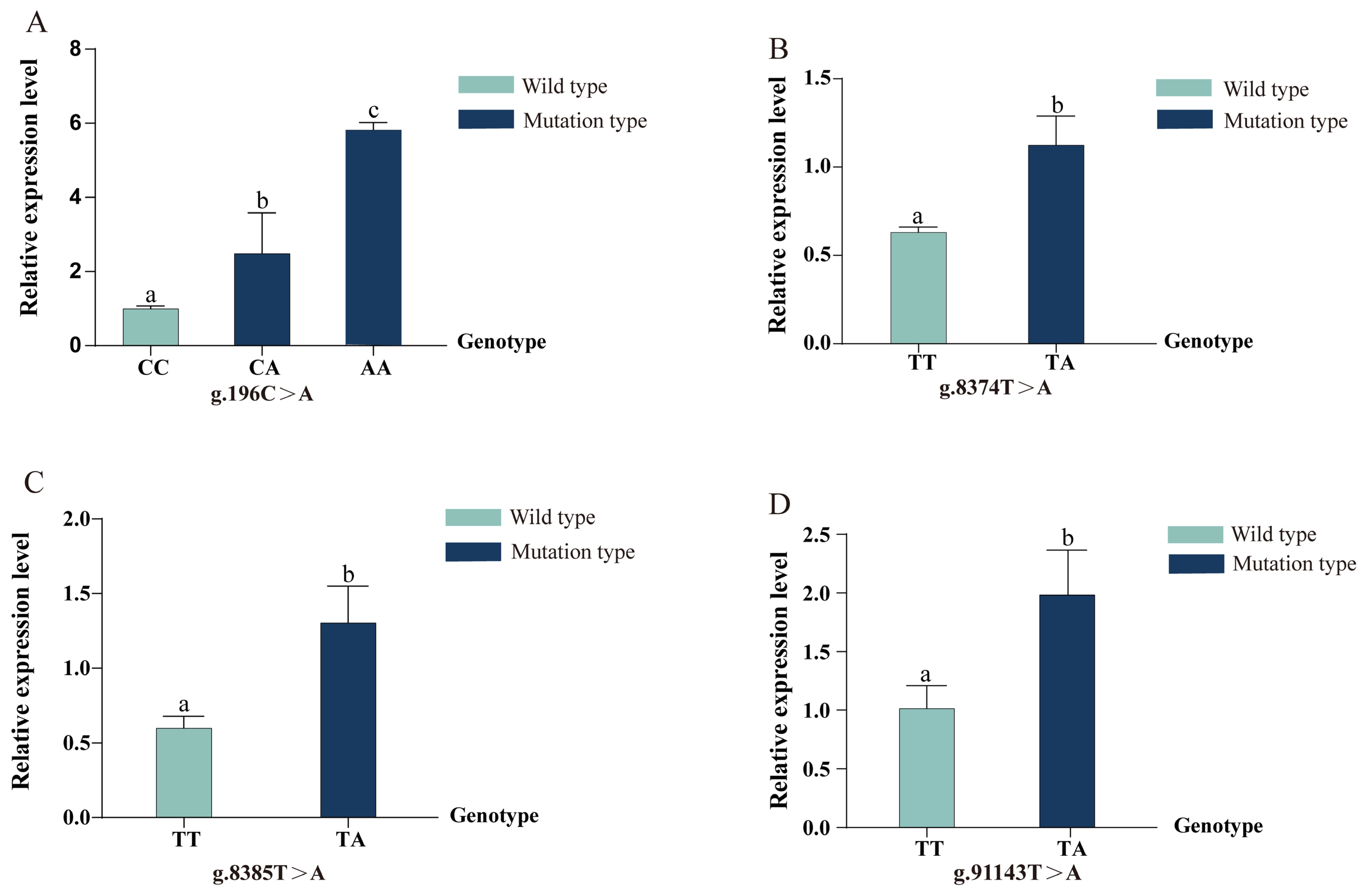

3.3. Expression Analysis of Different Genotypes at Mutation Sites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phat, L.T.; Huy, N.V.; Son, N.K.H.; Thuy, N.T.T.; Chat, T.T. Effects of salinity and substrates on the growth performance and survival rates of juvenile mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2024, 17, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, R.; Ayadi, H.; Koken, M.; Leignel, V. Homeostatic responses of crustaceans to salinity changes. Hydrobiologia 2017, 799, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, D.M.; Lei, X.Y.; Wang, S.; Wan, J.; Liu, H.J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Wang, G.; et al. Effects of acute salinity stress on osmoregulation, antioxidant capacity and physiological metabolism of female Chinese mitten crabs (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquaculture 2022, 552, 737989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Peng, Y.; Li, R.; Ji, Z.; Bekaert, M.; Mu, C.; Migaud, H.; Weiwei, S.; Shi, C.; Wang, C. Effects of long-term low-salinity on haemolymph osmolality, gill structure and transcriptome in mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Aquac. Rep. 2024, 38, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, L.; Wei, H.; Lu, J.; Mu, C.; Wang, C. Transcriptomic analysis of adaptive mechanisms in response to sudden salinity drop in the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Fang, S.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H. mRNA profile provides novel insights into stress adaptation in mud crab megalopa, Scylla paramamosain after salinity stress. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, G.; Gao, G.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Mu, C. Metabolic Changes in Scylla paramamosain During Adaptation to an Acute Decrease in Salinity. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 734519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.; Yang, P.; Qin, K.; Li, Y.; Fan, Z.; Li, W.; Gao, S.; Wang, C.; Mu, C.; Wang, H. Based on metabolomics analysis: Metabolic mechanism of intestinal tract of Scylla paramamosain under low-salt saline-alkali water aquaculture environment. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraschi, A.C.; Faria, S.C.; McNamara, J.C. Salt transport by the gill Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl(−) symporter in palaemonid shrimps: Exploring physiological, molecular and evolutionary landscapes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2021, 257, 110968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, P.; Li, J. Effects of salinity acclimation and eyestalk ablation on Na(+), K(+), 2Cl(−) cotransporter gene expression in the gill of Portunus trituberculatus: A molecular correlate for salt-tolerant trait. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsanit, P.; Chanchao, C.; Pairohakul, S. Effects of hypo-osmotic shock on osmoregulatory responses and expression levels of selected ion transport-related genes in the sesarmid crab Episesarma mederi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2024, 288, 111541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, E.L.; Fitzgibbon, Q.P.; Glendinning, S.; Lewis, C.L.; Banks, T.M.; Trotter, A.J.; Ventura, T.; Smith, G.G. Assessing Molecular Mechanisms of Stress Induced Salinity Adaptation in the Juvenile Ornate Spiny Lobster, Panulirus ornatus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Ruan, Z.; Lu, Z.-Q.; Li, Y.-F.; Luo, Y.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Liu, W.-S. Novel SNPs in the 3′UTR Region of GHRb Gene Associated with Growth Traits in Striped Catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus), a Valuable Aquaculture Species. Fishes 2022, 7, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasal, K.D.; Kumar, P.V.; Asgolkar, P.; Shinde, S.; Dhere, S.; Siriyappagouder, P.; Sonwane, A.; Brahmane, M.; Sundaray, J.K.; Goswami, M.; et al. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) array: An array of hope for genetic improvement of aquatic species and fisheries management. Blue Biotechnol. 2024, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, J.; Li, F. Identification of Growth-Associated Genes by Genome-Wide Association Study and Their Potential Application in the Breeding of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 611570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Kang, T.; Wan, H.; Mu, S.; Guan, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Ren, Y.; et al. Characterization of Myf6 and association with growth traits in swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xie, Y.; Gao, Z.; Niu, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, Y.; Qiao, H.; Fu, H. Studies on the Relationships between Growth and Gonad Development during First Sexual Maturation of Macrobrachium nipponense and Associated SNPs Screening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhong, P.; Wu, X.; Peng, K.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; et al. Construction of a genetic linkage map, QTLs mapping for low salinity and growth-related traits and identification of the candidate genes in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquac. Rep. 2022, 22, 100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, M.R.; Li, Y.D.; Jiang, S.G.; Yang, Q.B.; Jiang, S.; Yang, L.S.; Huang, J.H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, F.L. Identification of multifunctionality of the PmE74 gene and development of SNPs associated with low salt tolerance in Penaeus monodon. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 128, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.P.; Tu, D.D.; Yan, M.C.; Shu, M.A.; Shao, Q.J. Molecular characterization of a cDNA encoding Na(+)/K(+)/2Cl(−) cotransporter in the gill of mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) during the molt cycle: Implication of its function in osmoregulation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2017, 203, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Ma, Q.; Ma, C.-Y.; Ma, L. Isolation and characterization of gene-derived single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers in Scylla paramamosain. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2011, 39, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Ma, H.; Ma, C.; Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L. Characterization of 40 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) via Tm-shift assay in the mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 5467–5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Li, H.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Teng, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Ren, J. IBS 2.0: An upgraded illustrator for the visualization of biological sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W420–W426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Jiang, K.; Song, W.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y.; Wei, H.; Chen, K.; Qiao, Z.; Zhang, F.; et al. Two transcripts of HMG-CoA reductase related with developmental regulation from Scylla paramamosain: Evidences from cDNA cloning and expression analysis. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xiao, W.; Zou, Z.Y.; Zhu, J.-L.; Li, D.; Yu, J.; Yang, H. Correlation analysis of polymorphisms in promoter region and coding region of GHR and IGF-I genes with growth traits of two varieties of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 28, 2032–2047. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=2yANmoQUOTPK3FoJd55CkvWYUCS_tjY7WJix15G0DV6RkJHI6jAeu6ns0VQp5NRgQdP5Qok2AZmKvyQc6xyVKIe5ffLa1Mh6_efZjkdDKCqOWupN_GLR1aVCs3fkhEknZ0lzyHBsfI__8j6Y0YOzf_R_mSte7Zb9j5e9wuutk34l6owlcy2Jji605pziEAgm&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Gao, F.; Tong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cao, J.; Wang, M.; Yi, M.; Ke, X.; Yan, M.; Zhu, H. Screening of SNP of MYF6 Gene in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and Its Association Analysis with Growth Traits. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.M.; Anderson, C.A.; Pettersson, F.H.; Cardon, L.R.; Morris, A.P.; Zondervan, K.T. Basic statistical analysis in genetic case-control studies. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Muse, S.V. PowerMarker: An integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2128–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.Y.; He, L. Publisher Correction: SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.P.; Kahle, K.T.; Gamba, G. The SLC12 family of electroneutral cation-coupled chloride cotransporters. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, K.B.; Delpire, E. Physiology of SLC12 transporters: Lessons from inherited human genetic mutations and genetically engineered mouse knockouts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C693–C714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, C.A.; Onken, H.; McNamara, J.C. A structure-function analysis of ion transport in crustacean gills and excretory organs. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2008, 151, 272–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, J.C.; Faria, S.C. Evolution of osmoregulatory patterns and gill ion transport mechanisms in the decapod Crustacea: A review. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2012, 182, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, C.M.; Sternberg, M.J. The effects of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (nsSNPs) on protein-protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 3949–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.F.; Alonso Morales, L.A.; Kassen, R. Effects of Synonymous Mutations beyond Codon Bias: The Evidence for Adaptive Synonymous Substitutions from Microbial Evolution Experiments. Genome Biol Evol. 2021, 13, evab141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelschlaeger, P. Molecular Mechanisms and the Significance of Synonymous Mutations. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, J. Gene set based association analyses for the WSSV resistance of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Yang, H.; Hou, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Effects of synonymous mutation on transcription and translation efficiency of the Es-MSTN gene in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). J. Fish. China 2021, 45, 497−504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, C.; Roumeliotis, S.; Tripepi, G.; Spoto, B. Sample Size Calculation in Genetic Association Studies: A Practical Approach. Life 2023, 13, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Three lectures on case-control genetic association analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 2008, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, J.A.; Yu, D.; Bohra, A.; Ganie, S.A.; Varshney, R.K. Features and applications of haplotypes in crop breeding. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, D.; Dreisigacker, S. Haplotypes-based genetic analysis: Benefits and challenges. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2019, 23, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Lutz-Carrillo, D.; Quan, Y.; Liang, S. Taxonomic status and genetic diversity of cultured largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides in China. Aquaculture 2008, 278, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Bai, J. Comparative assessment of genomic SSR, EST–SSR and EST–SNP markers for evaluation of the genetic diversity of wild and cultured Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas Thunberg. Aquaculture 2014, 420–421, S85–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dildar, T.; Cui, W.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H. Aquatic Organisms in Response to Salinity Stress: Ecological Impacts, Adaptive Mechanisms, and Resilience Strategies. Biology 2025, 14, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Han, F. Integrative GWAS and eQTL analysis identifies genes associated with resistance to Vibrio harveyi infection in yellow drum (Nibea albiflora). Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1435469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peng, M.; Yang, C.; Li, Q.; Feng, P.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, D.; Zhao, Y. Genome-wide QTL and eQTL mapping reveal genes associated with growth rate trait of the Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchler, J.A.; Veitia, R.A. The gene balance hypothesis: Implications for gene regulation, quantitative traits and evolution. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joehanes, R.; Zhang, X.; Huan, T.; Yao, C.; Ying, S.X.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Demirkale, C.Y.; Feolo, M.L.; Sharopova, N.R.; Sturcke, A.; et al. Integrated genome-wide analysis of expression quantitative trait loci aids interpretation of genomic association studies. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.J.; Wagner, T.; Lee, H.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Oh, S. Enhancer–promoter specificity in gene transcription: Molecular mechanisms and disease associations. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 772–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okude, G.; Yamasaki, Y.Y.; Toyoda, A.; Mori, S.; Kitano, J. Genome-wide analysis of histone modifications can contribute to the identification of candidate cis-regulatory regions in the threespine stickleback fish. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamary, J.V.; Hurst, L.D. Evidence for selection on synonymous mutations affecting stability of mRNA secondary structure in mammals. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, R75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, K.I.; Meyer, D.; Holcomb, D.D.; Kames, J.; Hamasaki-Katagiri, N.; Katneni, U.K.; Hunt, R.C.; Ibla, J.C.; Kimchi-Sarfaty, C. Synonymous ADAMTS13 variants impact molecular characteristics and contribute to variability in active protein abundance. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 5364–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelamraju, Y.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Bhat-Nakshatri, P.; Nakshatri, H.; Janga, S.C. Mutational landscape of RNA-binding proteins in human cancers. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wen, H.; Qi, X.; Sun, D.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y. Integrated miRNA and mRNA analysis in gills of spotted sea bass reveals novel insights into the molecular regulatory mechanism of salinity acclimation. Aquaculture 2022, 575, 739778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, N.; Harshini, V.; Raval, I.; Patel, A.; Joshi, C. lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network in kidney transcriptome of Labeo rohita under hypersaline environment. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Sequence (5′~3′) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sp-NKCC-F1 | AGTCGCCAGTCGCAACAA | SNP screening |

| Sp-NKCC-R1 | GGTTAGGTTAGGTTAAGGTCGC | |

| Sp-NKCC-F2 | TCGTCTGCCACCAGTAGGA | SNP screening |

| Sp-NKCC-R2 | CTCACCTGGTTCTCCCTCAG | |

| Sp-NKCC-F3 | TACAAGACACAGCATCAGACAC | SNP screening |

| Sp-NKCC-R3 | GGTGAGGATGCAAGTCAATGA | |

| Sp-NKCC-F4 | GTTCTTCTACTTTGATGGTGCT | SNP screening |

| Sp-NKCC-R4 | AGCTAAGGCCAATGAAGCC | |

| Sp-NKCC-F5 | CCGGATTATCGAGAGTTTGAGA | SNP screening |

| Sp-NKCC-R5 | CACCTGTGGCATCTCTCAG | |

| Sp-NKCC-F6 | ACAGGTGACAAAGATGTGTATG | SNP screening |

| Sp-NKCC-R6 | CAGACAAAGGAGATGACGAAGA | |

| Sp-NKCC-F7 | ACCTCTCCCCGGATACAACTTA | SNP genotyping |

| Sp-NKCC-R7 | TCTGGTGCAGCTCGTCGAT | |

| Sp-NKCC-F8 | GCTGACCAGAGGGATTTTGTG | SNP genotyping |

| Sp-NKCC-R8 | TCCCTTGAATTATGGAGCAAAGGAA | |

| Sp-NKCC-F9 | CCCAGTCACCTGAAGATAAGCC | SNP genotyping |

| Sp-NKCC-R9 | TGAGGATGCAAGTCAATGACAAT | |

| Sp-NKCC-qRT-F | ATGGCATGGACAGCCATCTC | qRT-PCR |

| Sp-NKCC-qRT-R | CTATCCCCTGTTGTCGCTGG | |

| Sp-18S-qRT-F | GGGGTTTGCAATTGTCTCCC | qRT-PCR |

| Sp-18S-qRT-R | GGTGTGTACAAAGGGCAGGG |

| Locus | Allele | Amino Acid | Mutation Type | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g.196C>A | C-A | L-M | Nonsynonymous mutation | Exon |

| g.8374T>A | T-A | L | synonymous mutation | Exon |

| g.8385T>A | T-A | V-D | Nonsynonymous mutation | Exon |

| g.91143T>A | T-A | F-I | Nonsynonymous mutation | Exon |

| Group | Locus | Observed Heterozygosity | Expected Heterozygosity | Number of Effective Alleles | Polymorphic Information Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intolerant group | g.196C>A | 0.0200 | 0.0198 | 1.0202 | 0.0196 |

| g.8374T>A | 0.1800 | 0.1638 | 1.1959 | 0.1504 | |

| g.8385T>A | 0.2200 | 0.1958 | 1.2435 | 0.1766 | |

| g.91143T>A | 0.1800 | 0.1638 | 1.1959 | 0.1504 | |

| Tolerant group | g.196C>A | 0.3200 | 0.3432 | 1.5225 | 0.2843 |

| g.8374T>A | 0.3800 | 0.3318 | 1.4966 | 0.2768 | |

| g.8385T>A | 0.5000 | 0.3750 | 1.6000 | 0.3047 | |

| g.91143T>A | 0.6400 | 0.4352 | 1.7705 | 0.3405 |

| Haplotype | Tolerant Group (Freq.) | Intolerant Group (Freq.) | Chi2 | Fisher’s p | Pearson’s p | Odds Ratio [95%CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTTT | 52.18 (0.522) | 79.15 (0.792) | 16.826 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.266 [0.139~0.510] |

| ATTT | 4.04 (0.040) | 1.00 (0.010) | 1.894 | 0.1688 | 0.1687 | 4.188 [0.461~38.091 |

| CAAA | 8.38 (0.084) | 1.44 (0.014) | 5.191 | 0.0227 | 0.0227 | 6.290 [1.050~37.671] |

| CAAT | 5.47 (0.055) | 5.47 (0.055) | 0.000 | 0.9933 | 0.9933 | 1.005 [0.297~3.405] |

| CTTA | 9.62 (0.096) | 6.76 (0.068) | 0.559 | 0.4545 | 0.4545 | 1.477 [0.529~4.124] |

| AAAT | 5.07 (0.051) | 0.00 (0.000) | 5.230 | 0.0222 | 0.0222 | NA |

| ATAA | 4.96 (0.050) | 0.00 (0.000) | 5.113 | 0.0238 | 0.0238 | NA |

| ATTA | 7.09 (0.071) | 0.00 (0.000) | 7.389 | 0.0066 | 0.0066 | NA |

| Other | 3.18 (0.032) | 6.18 (0.062) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, C.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, K.; Wang, W.; Ma, C.; Zhang, F. Investigation of SNPs at NKCC Gene of Scylla paramamosain to Unveil the Low-Salinity Tolerance Phenotype. Fishes 2026, 11, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010031

Yin C, Ma Y, Liu Z, Wang X, Ma K, Wang W, Ma C, Zhang F. Investigation of SNPs at NKCC Gene of Scylla paramamosain to Unveil the Low-Salinity Tolerance Phenotype. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Chunyan, Yanqing Ma, Zhiqiang Liu, Xueyang Wang, Keyi Ma, Wei Wang, Chunyan Ma, and Fengying Zhang. 2026. "Investigation of SNPs at NKCC Gene of Scylla paramamosain to Unveil the Low-Salinity Tolerance Phenotype" Fishes 11, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010031

APA StyleYin, C., Ma, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Ma, K., Wang, W., Ma, C., & Zhang, F. (2026). Investigation of SNPs at NKCC Gene of Scylla paramamosain to Unveil the Low-Salinity Tolerance Phenotype. Fishes, 11(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010031