De Novo Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Primary Metabolic Capacity of the Sponge Xestospongia sp. from Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Total DNA Extraction

2.2. RNA Extraction, cDNA Library Construction, and Sequencing

2.3. De Novo Transcriptome Assembly and Annotation

2.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

2.5. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Validation

3. Results

3.1. Morphological and Molecular Identification of Xestospongia Species

3.2. Illumina Sequencing and De Novo Assembly

3.3. Gene Functional Annotation and Classification

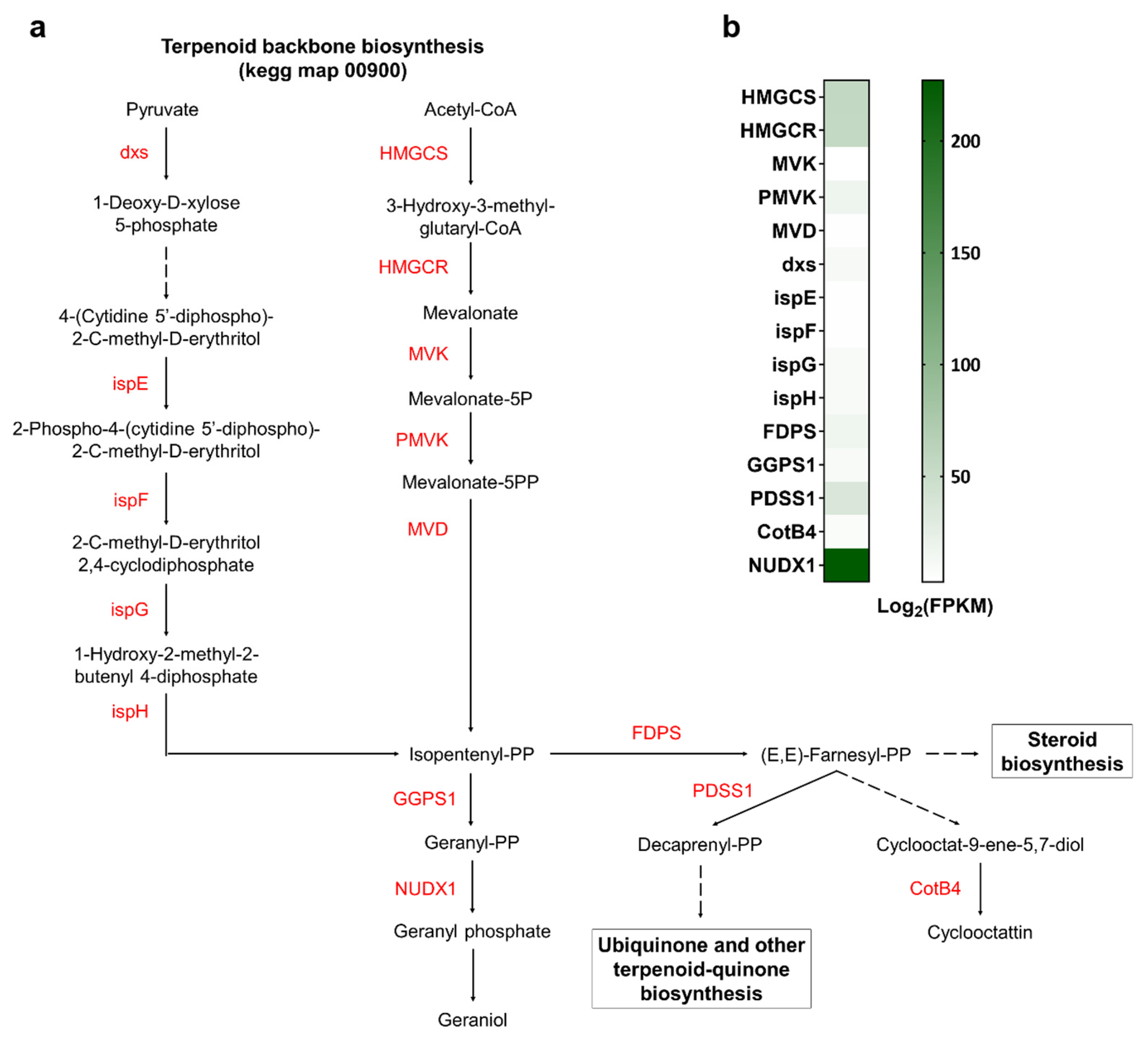

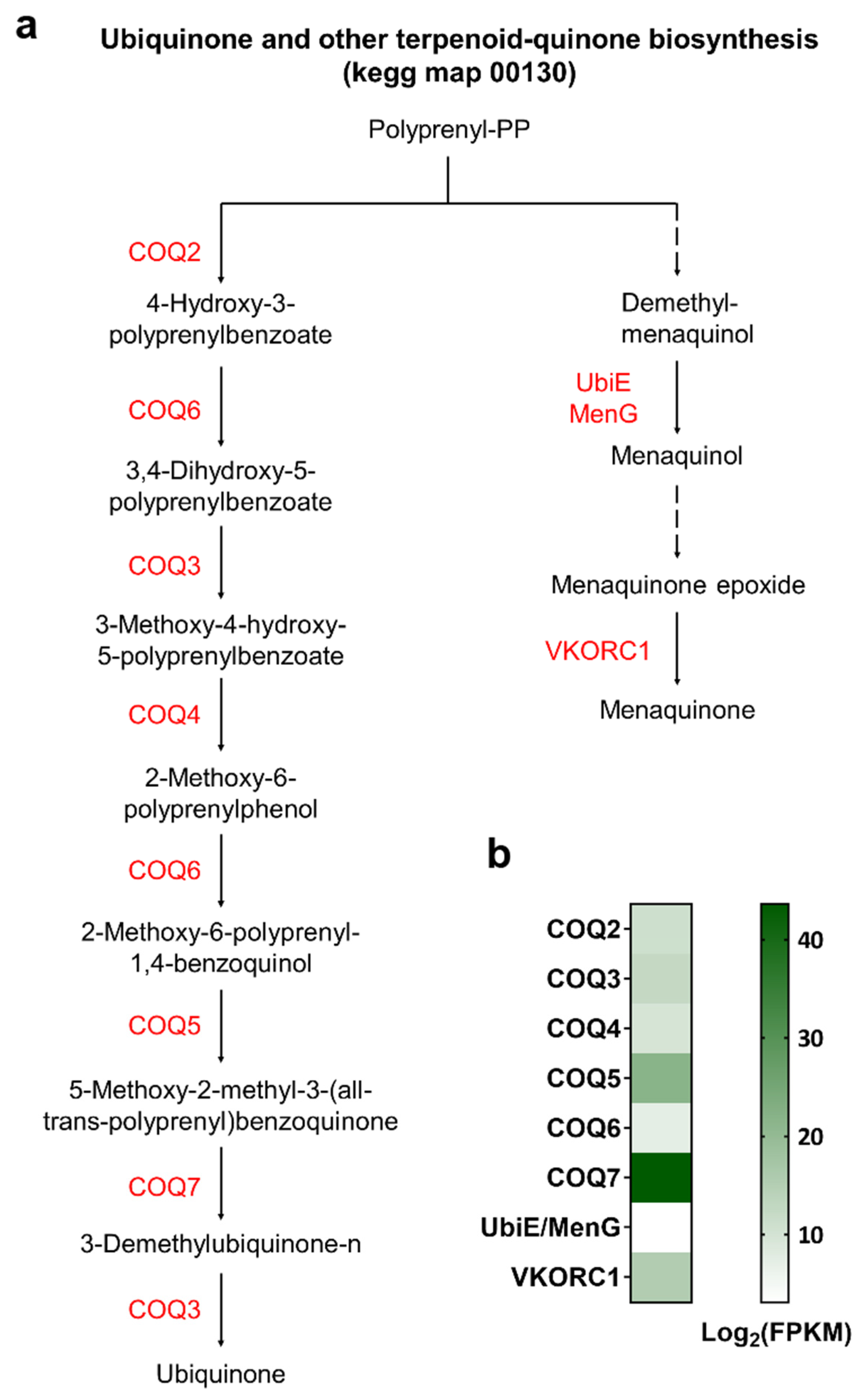

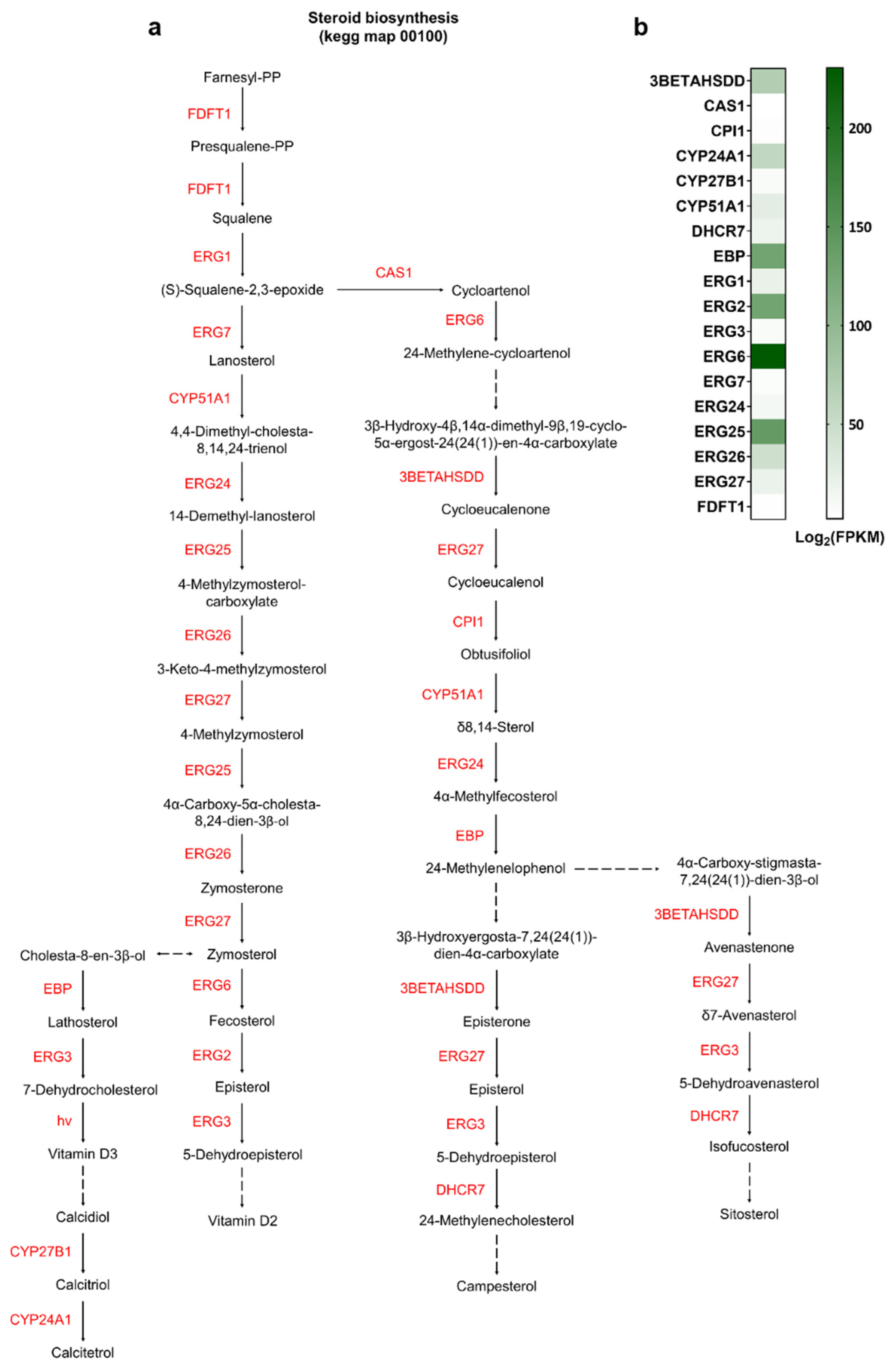

3.4. Identification of Genes Involved in Various Biosynthetic Pathways

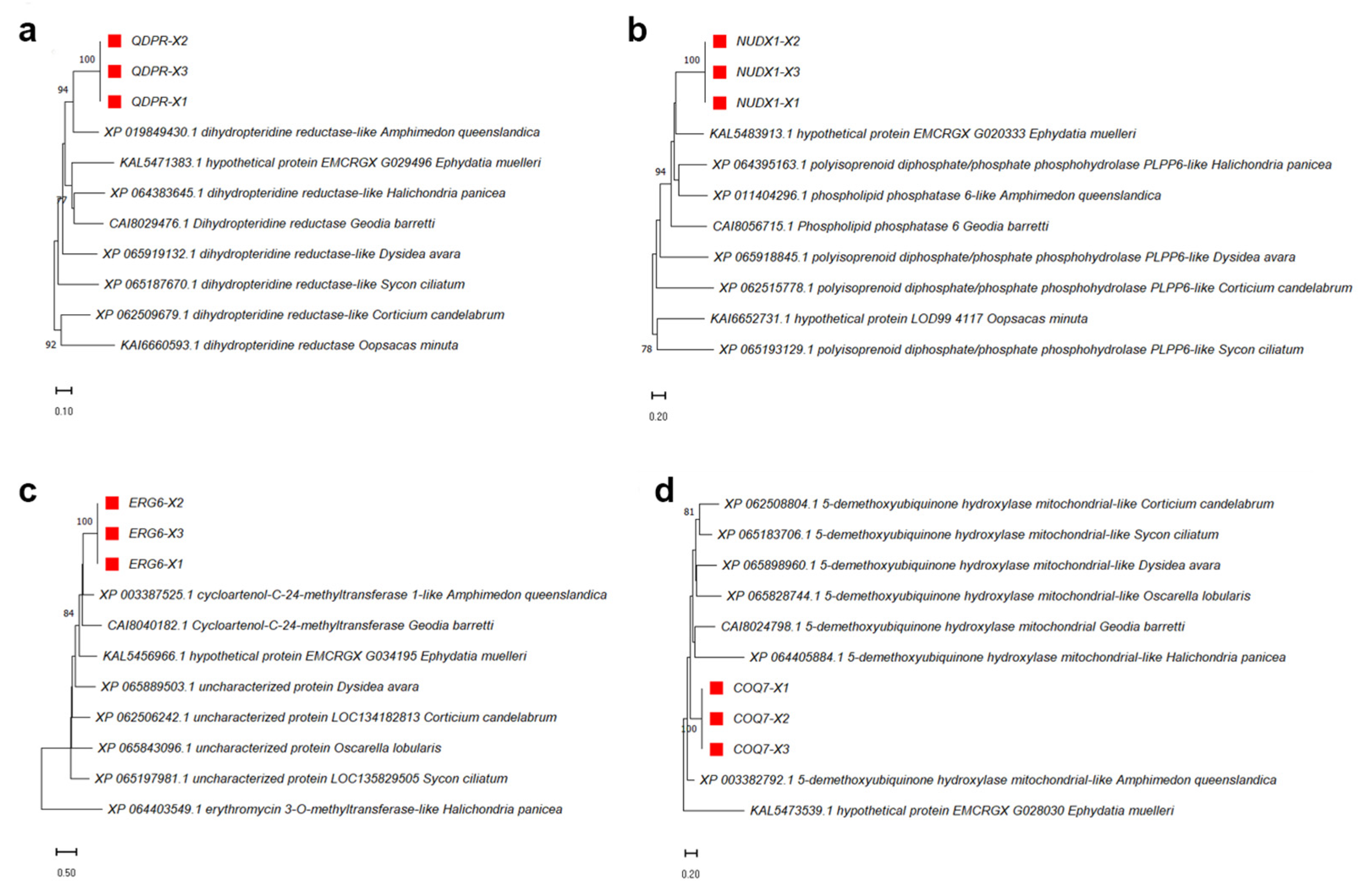

3.5. Phylogenetic Tree Analysis of Several High Expressed Proteins

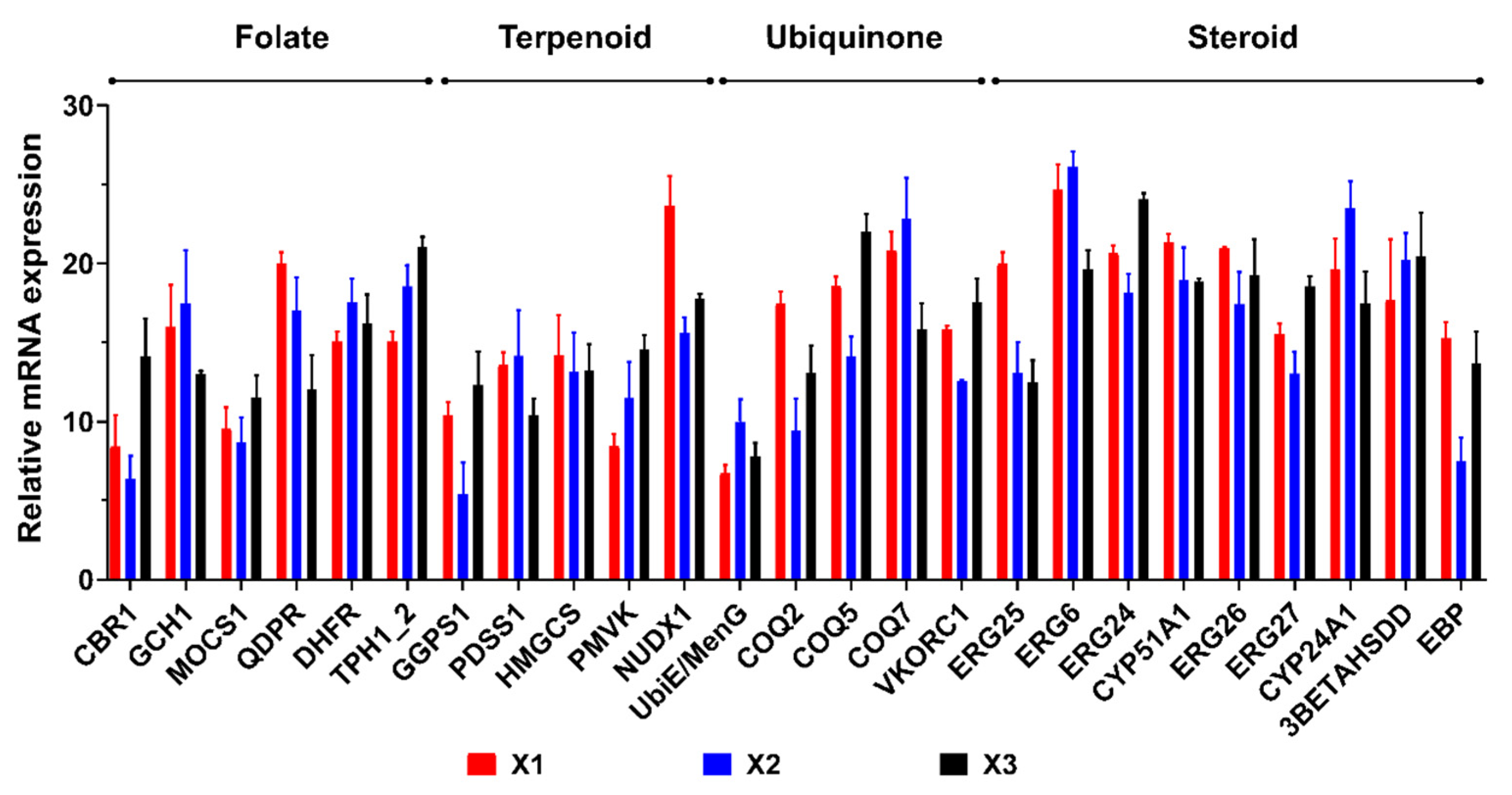

3.6. qRT-PCR Validation

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterization of the Host-Derived Transcriptomic Landscape

4.2. Sterol Metabolism: Elucidating the Host’s Biosynthetic Capacity

4.3. Cofactor Recycling and Host-Driven Signaling Mechanisms

4.4. Validating the “Host” Status via Metabolic Partitioning

4.5. Methodological Considerations and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Renard, E.; Gazave, E.; Fierro-Constain, L.; Schenkelaars, Q.; Ereskovsky, A.; Vacelet, J.; Borchiellini, C. Porifera (Sponges): Recent knowledge and new perspectives. In eLS; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swierts, T.; Peijnenburg, K.T.; de Leeuw, C.; Cleary, D.F.; Hornlein, C.; Setiawan, E.; Worheide, G.; Erpenbeck, D.; de Voogd, N.J. Lock, stock and two different barrels: Comparing the genetic composition of morphotypes of the indo-pacific sponge Xestospongia testudinaria. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberg, C.H.L. No taxonomy needed: Sponge functional morphologies inform about environmental conditions. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, C.L.; Labrie, M.; Jarett, J.K.; Lesser, M.P. Transcriptional activity of the giant barrel sponge, Xestospongia muta Holobiont: Molecular evidence for metabolic interchange. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodzori, F.A.; Mazlan, N.B.; Chong, W.S.; Ong, K.H.; Palaniveloo, K.; Shah, M.D. Metabolites and bioactivity of the marine Xestospongia sponges (Porifera, Demospongiae, Haplosclerida) of Southeast Asian waters. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.W.; Radax, R.; Steger, D.; Wagner, M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: Evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 295–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, U.; Piel, J.; Degnan, S.M.; Taylor, M.W. Genomic insights into the marine sponge microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swierts, T.; Cleary, D.F.R.; de Voogd, N.J. Prokaryotic communities of Indo-Pacific giant barrel sponges are more strongly influenced by geography than host phylogeny. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, D.A.; Grabenstatter, J.; de Mendoza, A.; Riesgo, A.; Ruiz-Trillo, I.; Summons, R.E. Sterol and genomic analyses validate the sponge biomarker hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2684–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riesgo, A.; Farrar, N.; Windsor, P.J.; Giribet, G.; Leys, S.P. The analysis of eight transcriptomes from all poriferan classes reveals surprising genetic complexity in sponges. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 1102–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, N.M.; Vinh, V.D.; Ouillon, S.; Lan, T.D.; Duong, N.T. Modelling impacts of climate change and anthropogenic activities on ecosystem state variables of water quality in the Cat Ba–Ha Long coastal area (Vietnam). Water 2025, 17, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, V.D.; Hai, N.M.; Purayil, S.P.; Lacroix, G.; Duong, N.T. Seasonal variation of coastal currents and residual currents in the Cat Ba—Ha Long coastal area (Vietnam): Results of coherens model. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 80, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, A.; Madrigal, P.; Tarazona, S.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Cervera, A.; McPherson, A.; Szcześniak, M.W.; Gaffney, D.J.; Elo, L.L.; Zhang, X.; et al. A survey of best practices for RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y. Integrated NR database in protein annotation system and its localization. Comput. Eng. 2006, 32, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairoch, A.; Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Mistry, J.; Mitchell, A.L.; Potter, S.C.; Punta, M.; Qureshi, M.; Sangrador-Vegas, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database: Towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D279–D285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Plaza, A.; Szklarczyk, D.; Botas, J.; Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Giner-Lamia, J.; Mende, D.R.; Kirsch, R.; Rattei, T.; Letunic, I.; Jensen, L.J.; et al. eggNOG 6.0: Enabling comparative genomics across 12 535 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D389–D394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Okuno, Y.; Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D277–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, D.; Luo, H.; Huo, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Guo, J.; et al. KOBAS-i: Intelligent prioritization and exploratory visualization of biological functions for gene enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W317–W325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Steinegger, M.; Breitwieser, F.; Söding, J.; Levy Karin, E. Fast and sensitive taxonomic assignment to metagenomic contigs. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 3029–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Zhu, Y.; Song, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; He, L.; Sun, W.; Xu, H.; et al. Transcriptional data mining of Salvia miltiorrhiza in response to methyl jasmonate to examine the mechanism of bioactive compound biosynthesis and regulation. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 152, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Poli, D.; Degnan, B.M.; Degnan, S.M. Ribosomal RNA-depletion provides an efficient method for successful dual RNA-seq expression profiling of a marine sponge holobiont. Mar. Biotechnol. 2022, 24, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvin, A.; Smadja, J.; Aknin, M.; Gaydou, E.M. Sterol composition and chemotaxonomic considerations in relation to sponges of the genus Xestospongia. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasanti, M.; Venturini, G. Nitric oxide in invertebrates. Mol. Neurobiol. 1998, 17, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langrehr, J.M.; Stadler, J.; Billiar, T.R.; Schraut, H.; Simmons, R.L.; Hoffman, R.A. Nitric oxide synthesis in sponge matrix allografts coincides with the initiation of the allogeneic response. In Host Defense Dysfunction in Trauma, Shock and Sepsis; Faist, E., Meakins, J.L., Schildberg, F.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musser, J.M.; Schippers, K.J.; Nickel, M.; Mizzon, G.; Kohn, A.B.; Pape, C.; Ronchi, P.; Papadopoulos, N.; Tarashansky, A.J.; Hammel, J.U.; et al. Profiling cellular diversity in sponges informs animal cell type and nervous system evolution. Science 2021, 374, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pham, L.B.H.; Do, H.Q.; Nguyen, C.M.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, H.H.; Nguyen, H.H.T.; Nguyen, K.L.; Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Le, Q.T.; et al. De Novo Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Primary Metabolic Capacity of the Sponge Xestospongia sp. from Vietnam. Fishes 2026, 11, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010023

Pham LBH, Do HQ, Nguyen CM, Nguyen TV, Nguyen HH, Nguyen HHT, Nguyen KL, Pham TH, Nguyen QH, Le QT, et al. De Novo Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Primary Metabolic Capacity of the Sponge Xestospongia sp. from Vietnam. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010023

Chicago/Turabian StylePham, Le Bich Hang, Hai Quynh Do, Chi Mai Nguyen, Tuong Van Nguyen, Hai Ha Nguyen, Huu Hong Thu Nguyen, Khanh Linh Nguyen, Thi Hoe Pham, Quang Hung Nguyen, Quang Trung Le, and et al. 2026. "De Novo Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Primary Metabolic Capacity of the Sponge Xestospongia sp. from Vietnam" Fishes 11, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010023

APA StylePham, L. B. H., Do, H. Q., Nguyen, C. M., Nguyen, T. V., Nguyen, H. H., Nguyen, H. H. T., Nguyen, K. L., Pham, T. H., Nguyen, Q. H., Le, Q. T., Tran, M. L., & Le, T. T. H. (2026). De Novo Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Primary Metabolic Capacity of the Sponge Xestospongia sp. from Vietnam. Fishes, 11(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010023