Essential Oils and Their Use as Anesthetics and Sedatives for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

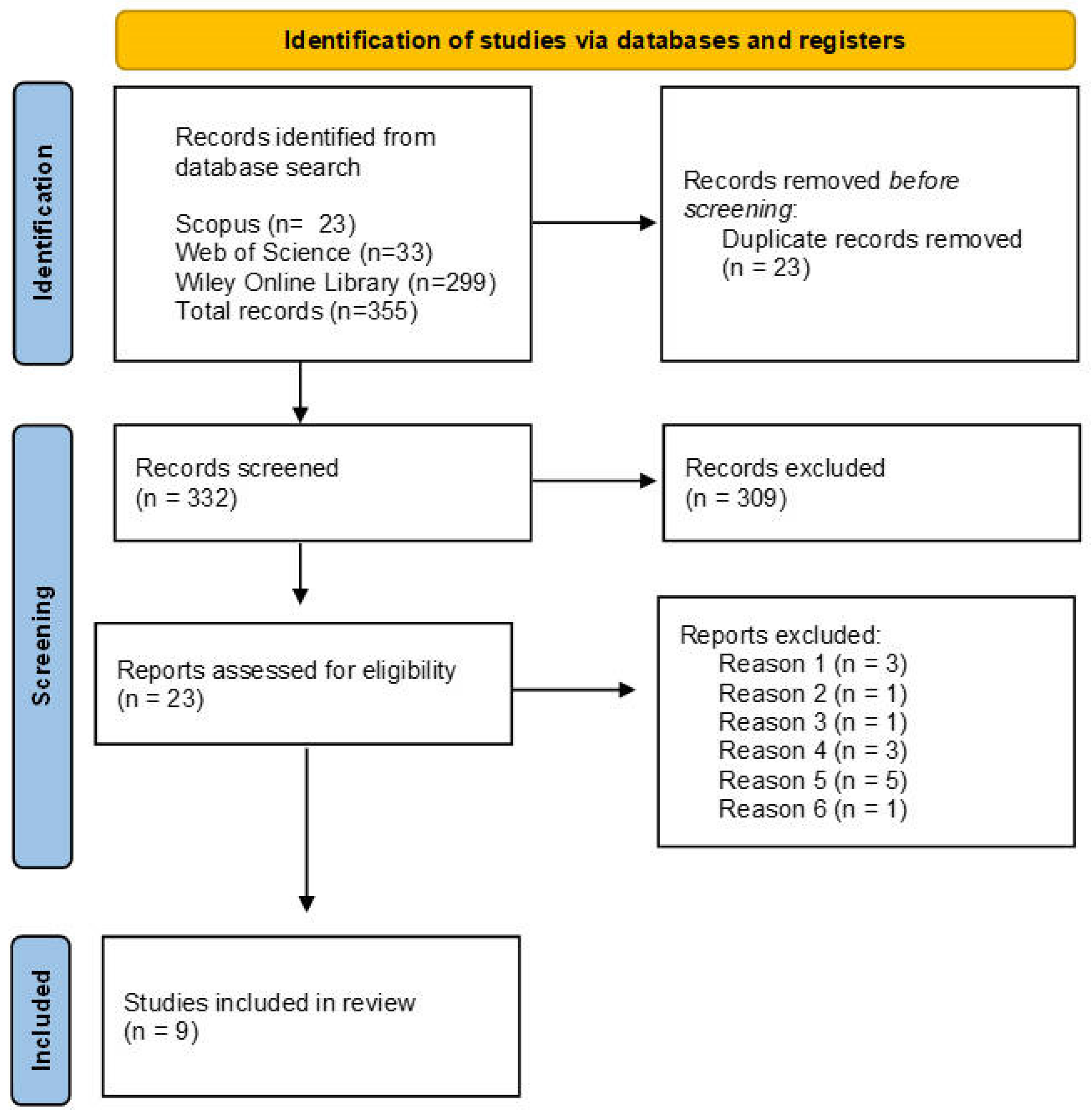

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Simulation of Concentration Versus Induction and Recovery Time

3.2. Deep Anesthesia Within 3 Min and Recovery: Comparisons Between EOs

3.3. Plasmatic Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Oliveira, I.C.; Oliveira, R.S.M.; Lemos, C.H.d.P.; de Oliveira, C.P.B.; Felix e Silva, A.; Lorenzo, V.P.; Lima, A.O.; da Cruz, A.L.; Copatti, C.E. Essential Oils from Cymbopogon citratus and Lippia sidoides in the Anesthetic Induction and Transport of Ornamental Fish Pterophyllum scalare. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 48, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shall, N.A.; Shewita, R.S.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; AlKahtane, A.; Alarifi, S.; Alkahtani, S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Sedeik, M.E. Effect of Essential Oils on the Immune Response to Some Viral Vaccines in Broiler Chickens, with Special Reference to Newcastle Disease Virus. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucinque, D.S.; Ferreira, P.F.; Leme, P.R.P.; Lapa-Guimarães, J.; Viegas, E.M.M. Ocimum americanum and Lippia alba Essential Oils as Anaesthetics for Nile Tilapia: Induction, Recovery of Apparent Unconsciousness and Sensory Analysis of Fillets. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttiarporn, P.; Taithaisong, T.; Namkhot, S.; Luangkamin, S. Enhanced Eugenol Composition in Clove Essential Oil by Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Ultrasonic Extraction and Microwave-Assisted Hydrodistillation. Molecules 2025, 30, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodur, T.; Oktavia, I.S.; Sulmartiwi, L. Effective Concentration of Herbal Anaesthetics Origanum vulgare L. Oil and Its Effects on Stress Parameters in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.; Deschamps, G.T.; Matter, F.d.L.; Bertoldi, F.C.; Aldegunde, M.; da Silva, D.F.; Lopes, C.; Jatobá, A.; Weber, R.A. The Anaesthetic Efficacy of Eucalyptus globulus Essential Oil on Silver Catfish (Rhamdia quelen). Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 5190–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elechosa, M.A.; Di Leo Lira, P.; Juárez, M.A.; Viturro, C.I.; Heit, C.I.; Molina, A.C.; Martínez, A.J.; López, S.; Molina, A.M.; van Baren, C.M.; et al. Essential Oil Chemotypes of Aloysia citrodora (Verbenaceae) in Northwestern Argentina. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2017, 74, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, C.F.S.; Ventura, A.S.; Jerônimo, G.T.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; de Matos, L.V.; da Silva, G.S.; Gonçalves, L.U.; Povh, J.A.; Martins, M.L. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Basil (Ocimum basilicum) Essential Oil as an Anesthetic for Tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum). Aqua. Intern. 2024, 32, 2923–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.M.; Ventura, A.S.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; da Silva, A.V.; Farias, C.F.S.; Costa, D.S.; de Souza, A.P.; Batista, D.V.V.; Fontes, S.T.; Jerônimo, G.T.; et al. Tissue Distribution of Ocimum basilicum Essential Oil in Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus after Anesthesia. Vet. Res. Commun. 2025, 49, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbice Bianchini, A.; Garlet, Q.I.; Rodrigues, P.; de Freitas Souza, C.; de Lima Silva, L.; Casale dos Santos, A.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B. Pharmacokinetics of S-(+)-Linalool in Silver Catfish (Rhamdia quelen) after Immersion Bath: An Anesthetic for Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2019, 506, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B.; Barbas, L.A.L. Sedative and Anesthetic Properties of Essential Oils and Their Active Compounds in Fish: A Review. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, G.B.; de Abreu, M.S.; dos Santos da Rosa, J.G.; Pinheiro, C.G.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Caron, B.O.; Baldisserotto, B.; Barcellos, L.J.G. Lippia alba and Aloysia triphylla Essential Oils Are Anxiolytic without Inducing Aversiveness in Fish. Aquaculture 2018, 482, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirghaed, A.T.; Yasari, M.; Mirzargar, S.S.; Hoseini, S.M. Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Anesthesia with Myrcene: Efficacy and Physiological Responses in Comparison with Eugenol. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 44, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.G.S.; Ferreira, A.L.; Acunha, R.M.G.; Oliveira, N.S.; Pompiani, N.; Oliveira, K.K.C.; Costa, D.C.; Chaves, F.C.M.; Campos, C.M. Essential Oil of Lippia origanoides as an Anesthetic for Piaractus mesopotamicus: Implications for Induction and Recovery Times, Ventilatory Frequency and Blood Responses after Biometric Management. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e286209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boaventura, T.P.; Souza, C.F.; Ferreira, A.L.; Favero, G.C.; Baldissera, M.D.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B.; Luz, R.K. Essential Oil of Ocimum gratissimum (Linnaeus, 1753) as Anesthetic for Lophiosilurus alexandri: Induction, Recovery, Hematology, Biochemistry and Oxidative Stress. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, M.E.; Martínez-Castellanos, G.; López-Méndez, M.C.; Reyes-Gonzalez, D.; González-Moreno, H.R. Production Costs and Growth Performance of Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Intensive Production Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Nader, M.M.; Salem, H.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Khafaga, A.F. Effect of Environmental Factors on Growth Performance of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer, Version 5. Available online: https://automeris.io/posts/version_5/ (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Drevon, D.; Fursa, S.R.; Malcolm, A.L. Intercoder Reliability and Validity of WebPlotDigitizer in Extracting Graphed Data. Behav. Modif. 2017, 41, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampke, E.H.; de Souza Barroso, M.E.; Marques, F.M.; Fronza, M.; Scherer, R.; Lemos, M.F.; Campagnaro, B.P.; Gomes, L.C. Genotoxic Effect of Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Brown Essential Oil on Fish (Oreochromis niloticus) and Mammal (Mus musculus). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 59, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; et al. Reporting Animal Research: Explanation and Elaboration for the ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekercioglu, N.; Al-Khalifah, R.; Ewusie, J.E.; Elias, R.M.; Thabane, L.; Busse, J.W.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Iorio, A.; Isayama, T.; Martínez, J.P.D.; et al. A Critical Appraisal of Chronic Kidney Disease Mineral and Bone Disorders Clinical Practice Guidelines Using the AGREE II Instrument. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, R.R.; de Souza, R.C.; Sena, A.C.; Baldisserotto, B.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Couto, R.D.; Copatti, C.E. Essential Oil of Aloysia triphylla in Nile Tilapia: Anaesthesia, Stress Parameters and Sensory Evaluation of Fillets. Aquac. Res. 2017, 48, 3383–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netto, J.D.L.; Oliveira, R.S.M.; Copatti, C.E. Efficiency of Essential Oils of Ocimum basilicum and Cymbopogum flexuosus in the Sedation and Anaesthesia of Nile Tilapia Juveniles. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017, 89, 2971–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.L.; dos Santos, F.A.C.; de Sena Souza, A.; Favero, G.C.; Pinheiro, C.G.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B.; Luz, R.K. Anesthetic and Sedative Efficacy of Essential Oil of Hesperozygis ringens and the Physiological Responses of Oreochromis niloticus after Biometric Handling and Simulated Transport. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 48, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohlenwerger, J.C.; Eduardo Copatti, C.; Cedraz Sena, A.; David Couto, R.; Baldisserotto, B.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Caron, B.O.; Schmidt, D. Could the Essential Oil of Lippia alba Provide a Readily Available and Cost-Effective Anaesthetic for Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)? Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 2016, 49, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Ferrari, F.T.; Barbosa, L.B.; Righi, A.; Laporta, L.; Garlet, Q.I.; Baldisserotto, B.; Heinzmann, B.M. Nanoemulsion Boosts Anesthetic Activity and Reduces the Side Effects of Nectandra grandiflora Nees Essential Oil in Fish. Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, P.C.; Lopes, E.M.; Ventura, A.S.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; da Silva, A.V.; Costa, D.S.; Tedesco, M.; Jerônimo, G.T.; Martins, M.L. Temperature-Induced Changes in the Hematological and Biochemical Parameters of Nile Tilapia Anesthetized with Ocimum basilicum. Aquac. Intern. 2025, 33, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.L.; Favero, G.C.; Boaventura, T.P.; de Freitas Souza, C.; Ferreira, N.S.; Descovi, S.N.; Baldisserotto, B.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Luz, R.K. Essential Oil of Ocimum gratissimum (Linnaeus, 1753): Efficacy for Anesthesia and Transport of Oreochromis niloticus. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinjogunla, V.F.; Usman, M.D.; Muazu, T.A.; Ajeigbe, S.O.; Musa, Z.A.; Ijoh, B.B.; Muhammad, Y.U.; Usman, B.I. Comparative Efficacy of Anesthetic Agents (Clove Oil and Sodium Bicarbonate) on Cultured African Catfish, Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) and Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758). Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 7, 3800–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.; Valentim, A.; Pereira, N.; Antunes, L.M. Anaesthetics and Analgesics Used in Adult Fish for Research: A Review. Lab. Anim. 2019, 53, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Pu, D.; Zheng, J.; Li, P.; Lü, H.; Wei, X.; Li, M.; Li, D.; Gao, L. Hypoxia-Induced Physiological Responses in Fish: From Organism to Tissue to Molecular Levels. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 267, 115609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilderhus, P.A.; Marking, L.L. Comparative Efficacy of 16 Anesthetic Chemicals on Rainbow Trout. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 1987, 7, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, S.M.; Taheri Mirghaed, A.; Yousefi, M. Application of Herbal Anaesthetics in Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2019, 11, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B.; Orhan, N. Effects of Thymol and Carvacrol Anesthesia on the Electrocardiographic and Behavioral Responses of the Doctor Fish Garra rufa. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, A.E.; Garlet, Q.I.; Da Cunha, J.A.; Bandeira Junior, G.; Brusque, I.C.M.; Salbego, J.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B. Monoterpenoids (Thymol, Carvacrol and S-(+)-Linalool) with Anesthetic Activity in Silver Catfish (Rhamdia quelen): Evaluation of Acetylcholinesterase and GABaergic Activity. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 50, e6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joca, H.C.; Cruz-Mendes, Y.; Oliveira-Abreu, K.; Maia-Joca, R.P.M.; Barbosa, R.; Lemos, T.L.; Lacerda Beirão, P.S.; Leal-Cardoso, J.H. Carvacrol Decreases Neuronal Excitability by Inhibition of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, N.N.; Liswaniso, G.M.; Haihambo, W.; Abasubong, K.P. The Effects of Origanum vulgare L. Essential Oils on Anaesthesia and Haemato-Biochemical Parameters in Mozambique Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) Post-Juveniles. Aquac. J. 2022, 2, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppenfeld, C.C.; Brasil, M.T.d.B.; Cavalcante, G.; da Silva, L.V.F.; Mourão, R.H.; da Cunha, M.A.; Baldisserotto, B. Anesthetic Induction of Juveniles of Rhamdia quelen and Ctenopharyngodon idella with Ocimum micranthum Essential Oil. Cienc. Rur. 2019, 49, e20180218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.C.S.; Denadai, Â.M.L.; Araújo, A.L.S.d.M.; Sousa, O.V.d. Methyl Chavicol: Chemical Aspects and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Health Sci. 2024, 4, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zheng, X.; Wu, J.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J. Assessment of the Molecular Mechanism in Fish Using Eugenol as Anesthesia Based on Network Pharmacology. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 50, 2191–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Paz, C.A.; da Costa, B.M.P.A.; Hamoy, M.K.O.; dos Santos, M.F.; da Rocha, L.L.; da Silva Deiga, Y.; de Sousa Barbosa, A.; do Amaral, A.L.G.; Câmara, T.M.; Barbosa, G.B.; et al. Establishing a Safe Anesthesia Concentration Window for Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) (Linnaeus 1758) by Monitoring Cardiac Activity in Eugenol Immersion Baths. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 278, 109839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, L.N.; Paiva, G.; de Carvalho Gomes, L. Óleo de Cravo Como Anestésico Em Adultos de Tilápia-Do-Nilo. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2010, 45, 1472–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, H.d.S.; Crispim, B.d.A.; Francisco, L.F.V.; Merey, F.M.; Kummrow, F.; Viana, L.F.; Inoue, L.A.K.A.; Barufatti, A. Genotoxicity Evaluation of Three Anesthetics Commonly Employed in Aquaculture Using Oreochromis niloticus and Astyanax lacustris. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 17, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, E.; Risha, E.; Rizk, A. Comparison Propofol and Eugenol Anesthetics Efficacy and Effects on General Health in Nile Tilapia. Aquaculture 2021, 534, 736251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.C.; Junior, G.B.; Zago, D.C.; Zeppenfeld, C.C.; da Silva, D.T.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B.; da Cunha, M.A. Anesthesia and Anesthetic Action Mechanism of Essential Oils of Aloysia triphylla and Cymbopogon flexuosus in Silver Catfish (Rhamdia quelen). Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2017, 44, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.C.; Bianchini, A.E.; Bandeira Junior, G.; Garlet, Q.I.; Brasil, M.T.d.B.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B.; Caron, B.O.; da Cunha, M.A. Essential Oil of Aloysia citriodora Paláu and Citral: Sedative and Anesthetic Efficacy and Safety in Rhamdia quelen and Ctenopharyngodon idella. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2022, 49, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D.G.; Sousa, S.D.G.; Silva, R.E.R.; Silva-Alves, K.S.; Ferreira-Da-Silva, F.W.; Kerntopf, M.R.; Menezes, I.R.A.; Leal-Cardoso, J.H.; Barbosa, R. Essential Oil of Lippia alba and Its Main Constituent Citral Block the Excitability of Rat Sciatic Nerves. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2015, 48, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Batista, E.; Brandão, F.R.; Majolo, C.; Inoue, L.A.K.A.; Maciel, P.O.; de Oliveira, M.R.; Chaves, F.C.M.; Chagas, E.C. Lippia Alba Essential Oil as Anesthetic for Tambaqui. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisabetsky, E.; Marschner, J.; Onofre Souza, D. Effects of Linalool on Glutamatergic System in the Rat Cerebral Cortex. Neurochem. Res. 1995, 20, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhang, N.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Sun, L. Beta-Myrcene as a Sedative–Hypnotic Component from Lavender Essential Oil in DL-4-Chlorophenylalanine-Induced-Insomnia Mice. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva e Silva, J.d.; Tryers, E.G.; da Silva, A.N.C.; da Costa, B.M.P.A.; da Silva, T.V.N.; Torres, M.F.; Hamoy, M.; Barbas, L.A.L. Implications of Eucalyptol Anaesthesia on Juvenile Tambaqui Colossoma macropomum: Examining Behavioural, Muscular, Cardiac, and Haematological Responses. Aquaculture 2025, 594, 741397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, H.; Mizuta, K.; Fujita, T.; Kumamoto, E. Inhibition by Menthol and Its Related Chemicals of Compound Action Potentials in Frog Sciatic Nerves. Life Sci. 2013, 92, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.L.; Souza, A.d.S.; Santos, F.A.C.d.; Pinheiro, C.G.; Favero, G.C.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B.; Luz, R.K. Hesperozygis ringens Essential Oil as an Anesthetic for Colossoma macropomum during Biometric Handling. Ciênc. Rur. 2023, 53, e20220264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlet, Q.I.; Souza, C.F.; Rodrigues, P.; Descovi, S.N.; Martinez-Rodríguez, G.; Baldisserotto, B.; Heinzmann, B.M. GABAa Receptor Subunits Expression in Silver Catfish (Rhamdia quelen) Brain and Its Modulation by Nectandra grandiflora Nees Essential Oil and Isolated Compounds. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 376, 112178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlet, Q.I.; Pires, L.C.; Silva, D.T.; Spall, S.; Gressler, L.T.; Bürger, M.E.; Baldisserotto, B.; Heinzmann, B.M. Effect of (+)-Dehydrofukinone on GABAA Receptors and Stress Response in Fish Model. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, e4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Eligibility Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| (1) studies on EOs in tilapia, (2) university theses, literature reviews, book chapters, and technical articles were not considered, (3) only articles in English, (4) presented induction and recovery times, and (5) studies found in the databases described above. | (1) studies on transport, (2) EO nanoparticles, (3) isolated EO compounds, (4) non-alcohol diluent, (5) less than three concentrations, and (6) non-immersion induction. |

| Stage | Description | Behavior Displayed |

|---|---|---|

| I | Light Sedation | Decreased reactivity to visual and vibrational stimuli. Opercular and locomotor activity slightly reduced. Darker color. |

| II | Deep Sedation | Partial loss of equilibrium—loss of balance in the water. Tactile response only to pressure on the caudal fin or peduncle. Increased opercular rate. |

| III | Light Anesthesia | Total loss of equilibrium—locomotion stops. Decreased opercular rate. Fish turned over. |

| IV | Deep Anesthesia | Loss of reflex activity—lack of response to external stimuli, even pressure on the caudal fin or peduncle. Minimum opercular rate, nearing cessation. |

| Recovery | Recovery of equilibrium and active swimming |

| EOs | Main Compounds (%) | Score (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aloysia citriodora (A. triphylla) | geranial (28.97), neral (16.12), β-caryophyllene (8.50) | 85 | [25] |

| Cymbopogon flexuosus | geranial (50.13), neral (40.32) | 85 | [26] |

| Hesperozygis ringens | pulegone (98.15) | 85 | [27] |

| Lippia alba | linalool (47.66), β-myrcene (11.02), eucalyptol (9.77) | 90 | [28] |

| Nectandra grandiflora | dehydrofukinone (28.32), eremophilene (11.53), eremophil-11-en-10ol (7.51) | 75 | [29] |

| Ocimum basilicum | linalool (53.35) | 85 | [26] |

| Ocimum basilicum2 | methyl-chavicol (70.04), linalool (24.59) | 80 | [30] |

| Ocimum gratissimum | eugenol (73.6) | 85 | [31] |

| Origanum vulgare | carvacrol (78.16) | 90 | [5] |

| Syzygium aromaticum | eugenol (67.0) | 70 | [32] |

| EOs\Concentration (μL/L) | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage IV | Time (s) | |||||

| Aloysia citriodora | 423 | 333 | 243 | 63 | [25] | |

| Cymbopogon flexuosus | 1405 | 1279 | 1027 | 775 | 271 | [26] |

| Hesperozygis ringens | ND | ND | ND | 202 | 154 | [27] |

| Lippia alba | ND | ND | 823 | 571 | 69 | [28] |

| Nectandra grandiflora | 1699 | 1565 | 1299 | 1032 | ND | [29] |

| Ocimum basilicum | 682 | 622 | 502 | 382 | 142 | [26] |

| Ocimum basilicum2 | 183 | 151 | 100 | 66 | 54 | [30] |

| Ocimum gratissimum | 311 | 171 | 41 | 111 | ND | [31] |

| Origanum vulgare | 76 | 53 | ND | ND | ND | [5] |

| Syzygium aromaticum | 702 | 349 | ND | ND | ND | [32] |

| Recovery | ||||||

| Aloysia citriodora | ND | 153 | 166 | 179 | 205 | [25] |

| Cymbopogon flexuosus | 255 | 269 | 297 | 325 | 380 | [26] |

| Hesperozygis ringens | ND | ND | ND | 152 | 151 | [27] |

| Lippia alba | ND | 127 | 247 | 187 | [28] | |

| Nectandra grandiflora | 1423 | 1786 | 1806 | 1807 | 1807 | [29] |

| Ocimum basilicum | 282 | 274 | 258 | 241 | 210 | [26] |

| Ocimum basilicum2 | 238 | 282 | 372 | 467 | 669 | [30] |

| Ocimum gratissimum | 568 | 345 | 138 | 249 | ND | [31] |

| Origanum vulgare | 223 | 215 | ND | ND | ND | [5] |

| Syzygium aromaticum | 443 | 714 | ND | ND | ND | [32] |

| EOS | Conc (μL/L) | RTime (s) | Equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloysia citriodora | 370 | 188 | (i) y = 512.79 − 0.90x; r2 = 0.80 | [25] |

| (r) y = 140.29 + 0.13x; r2 = 0.97 | ||||

| Cymbopogon flexuosus | 536 | 351 | (i) y = 1531.42 − 2.52x; r2 = 0.82 | [26] |

| (r) y= 410.03 − 0.11x; r2 = 0.86 | ||||

| Hesperozygis ringens | 402 | 151 | (i) y = 2911.8e − 0.011x; r2 = 1 | [27] |

| (r) y = 150,495 + (153,055 − 150,495)/(1 + (x/396,709)12,106); r2 = 0.94 | ||||

| Lippia alba | 456 | 234 | (i) y = 1325,624 − 2514x; r2 = 0.930 | [28] |

| (r) y = −413.22 + 3.70x − 0.005x2; r2 = 1 | ||||

| Nectandra grandiflora | 602 | 1807 | (i) y = 667.06 − 0.3588x; r2 = 0.9930 | [29] |

| (r) y = 71.46 + (1807.68 − 71.46)/(1 + (x/37.72)−4.47); r2 = 0.96 | ||||

| Ocimum gratissimum | 96 | 226 | (i) y = 501.04 − 4.30x + 0.01 x2 | [31] |

| (r) y = 73.04 + 1.59x; r2 = 0.9732 | ||||

| Ocimum basilicum | 468 | 215 | (i) y = 741.83 − 1.20x; r2 = 0.83 | [26] |

| (r) y = 289.87 − 0.16x; r2 = 0.640 | ||||

| Ocimum basilicum2 | 55 | 242 | (i) y = 0.0009x2 − 0.782x + 220.26 | [30] |

| (r) y = 0.0002x2 + 0.85x + 194.67; r2 = 0.9732 | ||||

| Origanum vulgare | 20 * | 148 | (i)—no significant relationship | [5] |

| (r) y =234.26 (1 − e(−0.05x)); r2 = 0.8664 | ||||

| Syzygium aromaticum | 118 | 812 | (i) y =142.1 − 0.13x; r2 = 0.9169 | [32] |

| (r) y = 171 + 5.43x; r2 = 0.9708 |

| Time After Exposure (h) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter/EOs | Concentration (µL/L) | 0 (vc%) | 1 (vc%) | 2 (vc%) | 4 (vc%) | 6 (vc%) | 12 (vc%) | 24 (vc%) | Reference |

| Glucose | |||||||||

| Aloysia citriodora | 300 | - | ↑ 66 | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | [25] |

| Hesperozygis ringens | 600 | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | ND | - | [27] |

| Lippia alba | 500 | - | ↑ 156 | ND | ↑ 140 | ND | ND | ND | [28] |

| Origanum vulgare | 60 | ↑ 399 | ND | ↑ 343 | ND | ↑ 176 | ↑ 196 | ↑ 191 | [5] |

| Ocimum gratissimum | 90 | - | - | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [31] |

| Ocimum gratissimum | 150 | - | - | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [31] |

| Cortisol | |||||||||

| Aloysia citriodora | 300 | - | ↓ 367 | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | [25] |

| Lippia alba | 500 | - | - | ND | ↓ 145 | ND | ND | ND | [28] |

| Origanum vulgare | 60 | ↑ 161 | ND | ↓ 39 | ND | ↓ 45 | ↓ 71 | ↓ 58 | [5] |

| Paraoxionase | |||||||||

| Aloysia citriodora | 300 | - | - | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | [25] |

| Lippia alba | 500 | - | - | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | [28] |

| Lactate | |||||||||

| Aloysia citriodora | 300 | ↑ 268 | - | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | [25] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Visoni, B.M.; de Melo, T.P.; Descovi, S.N.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Baldisserotto, B. Essential Oils and Their Use as Anesthetics and Sedatives for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): A Systematic Review. Fishes 2026, 11, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010019

Visoni BM, de Melo TP, Descovi SN, Heinzmann BM, Baldisserotto B. Essential Oils and Their Use as Anesthetics and Sedatives for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): A Systematic Review. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleVisoni, Bruno Mendes, Thaise Pinto de Melo, Sharine Nunes Descovi, Berta Maria Heinzmann, and Bernardo Baldisserotto. 2026. "Essential Oils and Their Use as Anesthetics and Sedatives for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): A Systematic Review" Fishes 11, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010019

APA StyleVisoni, B. M., de Melo, T. P., Descovi, S. N., Heinzmann, B. M., & Baldisserotto, B. (2026). Essential Oils and Their Use as Anesthetics and Sedatives for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): A Systematic Review. Fishes, 11(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010019