Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Acute Phase Response Related Molecules in Micropterus salmoides During Streptococcus Agalactiae Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish and Pathogens

2.2. Infection and Sampling

2.3. Primer Design

2.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.5. Total RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription and qPCR

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sequences and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Acute Phase Response Related Molecules

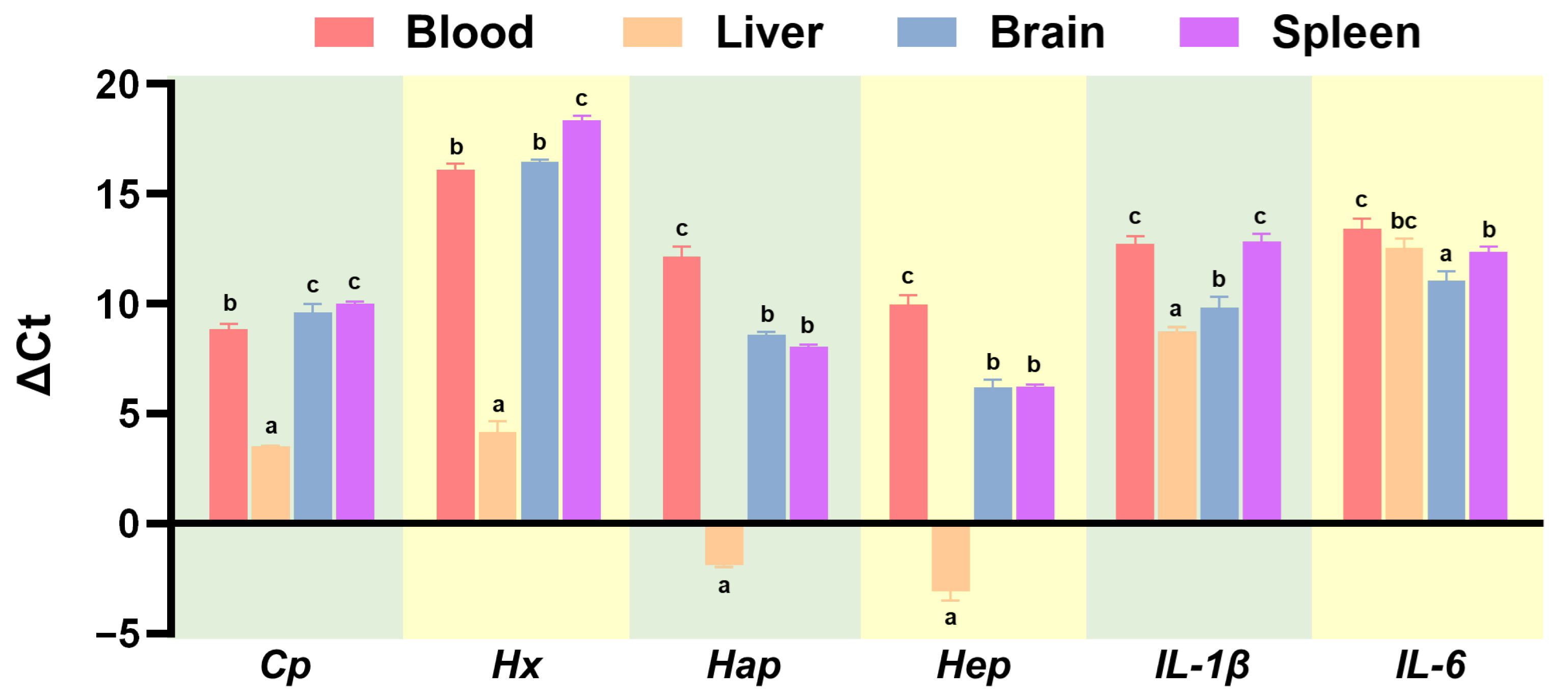

3.2. Gene Expression Profiles in Healthy Largemouth Bass Tissues

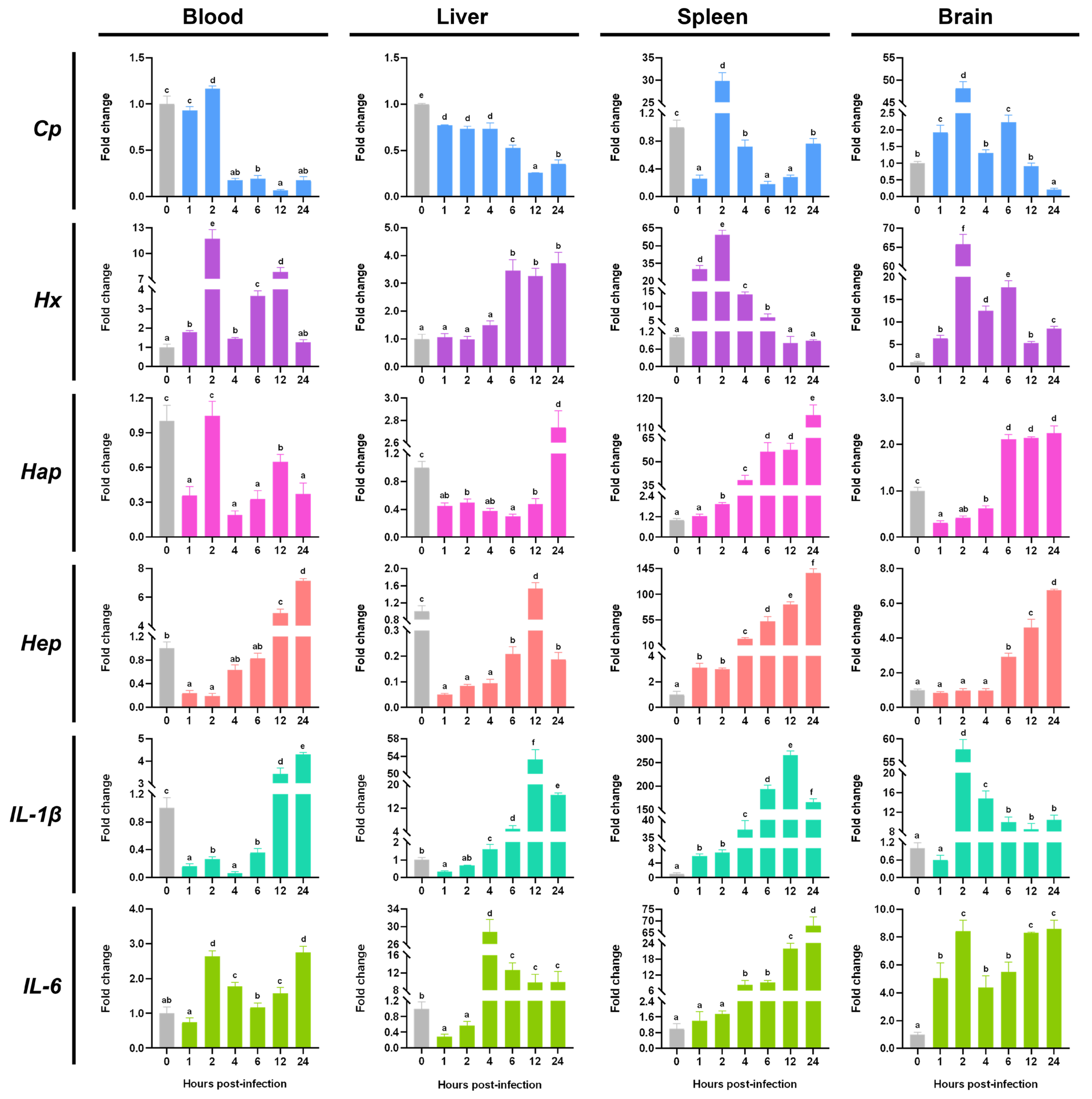

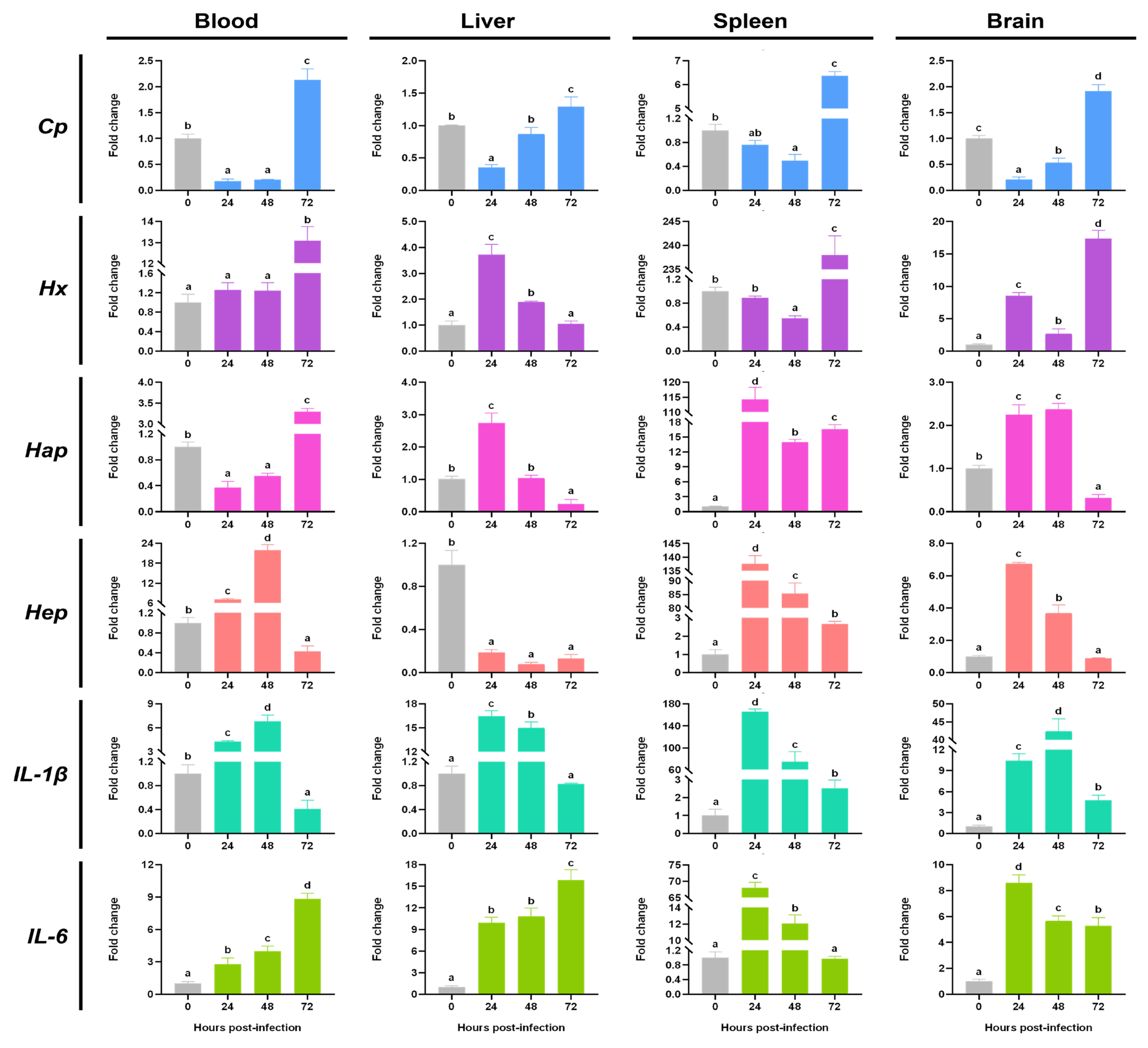

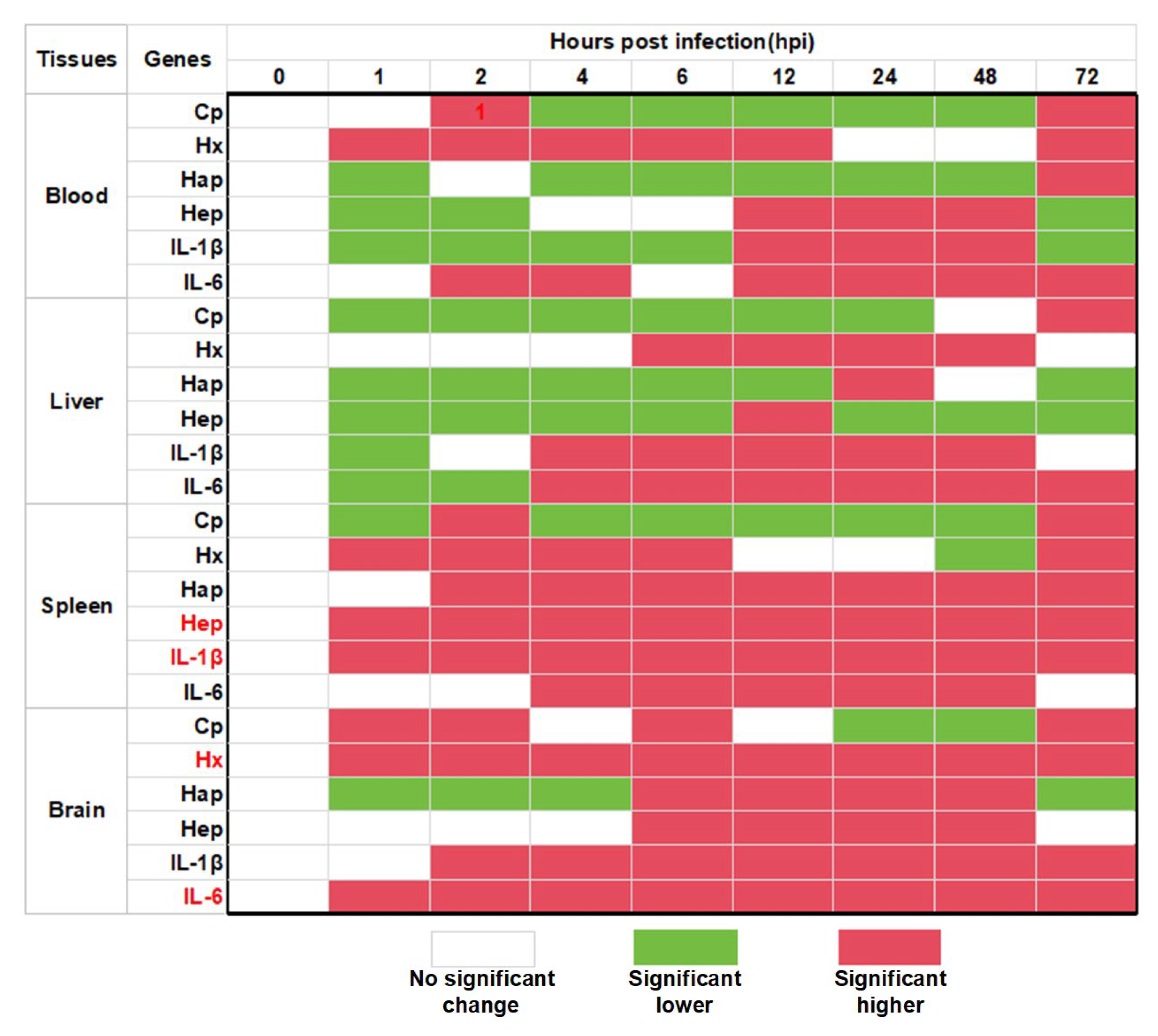

3.3. The Expression Changes of Acute Phase Response Related Molecules During the S. agalactiae Infection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gordon, A.H.; Koj, A. (Eds.) The Acute Phase Response to Injury and Infection; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bayne, C.J.; Gerwick, L. The acute phase response and innate immunity of fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2001, 25, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slauson, D.O.; Cooper, B.J. Mechanisms of Disease: A Textbook of Comparative General Pathology; Mosby Inc.: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, V.; Behera, B. Acute phase proteins and their potential role as an indicator for fish health and in diagnosis of fish diseases. Protein Pept. Lett. 2017, 24, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tothova, C.; Nagy, O.; Kovac, G. Acute phase proteins and their use in the diagnosis of diseases in ruminants: A review. Vet. Med. 2014, 59, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersall, P.; Bell, R. Acute phase proteins: Biomarkers of infection and inflammation in veterinary medicine. Vet. J. 2010, 185, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyhs, U.; Kulkas, L.; Katholm, J.; Waller, K.P.; Saha, K.; Tomusk, R.J.; Zadoks, R.N. Streptococcus agalactiae serotype IV in humans and cattle, northern Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochet, M.; Couvé, E.; Zouine, M.; Vallaeys, T.; Rusniok, C.; Lamy, M.-C.; Buchrieser, C.; Trieu-Cuot, P.; Kunst, F.; Poyart, C. Genomic diversity and evolution within the species Streptococcus agalactiae. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8, 1227–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, E.J.; Shilton, C.; Benedict, S.; Kong, F.; Gilbert, G.; Gal, D.; Godoy, D.; Spratt, B.; Currie, B.J. Necrotizing fasciitis in captive juvenile Crocodylus porosus caused by Streptococcus agalactiae: An outbreak and review of the animal and human literature. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007, 135, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phares, C.R.; Lynfield, R.; Farley, M.M.; Mohle-Boetani, J.; Harrison, L.H.; Petit, S.; Craig, A.S.; Schaffner, W.; Zansky, S.M.; Gershman, K. Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999–2005. JAMA 2008, 299, 2056–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.D.; Springman, A.C.; Lehotzky, E.; Lewis, M.A.; Whittam, T.S.; Davies, H.D. Multilocus sequence types associated with neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis and meningitis in Canada. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Li, L.-P.; Wang, R.; Liang, W.-W.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Lei, A.-Y.; Huang, W.-Y.; Gan, X. PCR detection and PFGE genotype analyses of streptococcal clinical isolates from tilapia in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 159, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondad-Reantaso, M.G.; Subasinghe, R.P.; Arthur, J.R.; Ogawa, K.; Chinabut, S.; Adlard, R.; Tan, Z.; Shariff, M. Disease and health management in Asian aquaculture. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 132, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanyuk, N.; Kong, F.; Ko, D.; Gilbert, G.L.; Supamattaya, K. Occurrence of rare genotypes of Streptococcus agalactiae in cultured red tilapia Oreochromis sp. and Nile tilapia O. niloticus in Thailand—Relationship to human isolates? Aquaculture 2008, 284, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pionnier, N.; Adamek, M.; Miest, J.J.; Harris, S.J.; Matras, M.; Rakus, K.; Irnazarow, I.; Hoole, D. C-reactive protein and complement as acute phase reactants in common carp Cyprinus carpio during CyHV-3 infection. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2014, 109, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Hayes, M.; Simko, E.; Lumsden, J. Plasma proteomic analysis of the acute phase response of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to intraperitoneal inflammation and LPS injection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2006, 30, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwick, L.; Steinhauer, R.; Lapatra, S.; Sandell, T.; Ortuno, J.; Hajiseyedjavadi, N.; Bayne, C. The acute phase response of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) plasma proteins to viral, bacterial and fungal inflammatory agents. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2002, 12, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayne, C.; Gerwick, L.; Fujiki, K.; Nakao, M.; Yano, T. Immune-relevant (including acute phase) genes identified in the livers of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, by means of suppression subtractive hybridization. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2001, 25, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Chen, S.; Cao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Mo, D.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Dong, M.; Liu, Z.; Xu, A. Acute phase response in zebrafish upon Aeromonas salmonicida and Staphylococcus aureus infection: Striking similarities and obvious differences with mammals. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peatman, E.; Baoprasertkul, P.; Terhune, J.; Xu, P.; Nandi, S.; Kucuktas, H.; Li, P.; Wang, S.; Somridhivej, B.; Dunham, R. Expression analysis of the acute phase response in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) after infection with a Gram-negative bacterium. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2007, 31, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlie-Silva, I.; Klein, A.; Gomes, J.M.; Prado, E.J.; Moraes, A.C.; Eto, S.F.; Fernandes, D.C.; Fagliari, J.J.; Junior, J.D.C.; Lima, C. Acute-phase proteins during inflammatory reaction by bacterial infection: Fish-model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Li, X.; Chen, N.; Mu, L.; Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; Han, K.; Huang, Y.; Wang, B.; Jian, J.; et al. Hemopexin as an acute phase protein regulates the inflammatory response against bacterial infection of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 187, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleç, A.K.; Cengizler, I. Determination of acute phase proteins after experimental Streptococcus iniae infection in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2012, 36, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Y.; Wang, K.Y.; Xiao, D.; Chen, D.F.; Geng, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Wang, E.L.; Huang, J.L.; Xiao, G.Y. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral DNA vaccine encoding Sip of Streptococcus agalactiae from Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus delivered by live attenuated Salmonella typhimurium. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 38, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, F.M.; Elshopakey, G.E.; Aziza, A.E. Ameliorative effects of dietary Chlorella vulgaris and β-glucan against diazinon-induced toxicity in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 96, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piamsomboon, P.; Thanasaksiri, K.; Murakami, A.; Fukuda, K.; Takano, R.; Jantrakajorn, S.; Wongtavatchai, J. Streptococcosis in freshwater farmed seabass Lates calcarifer and its virulence in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture 2020, 523, 735189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Zhong, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, C.; et al. Current status and application of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) germplasm resources. Reprod. Breed. 2024, 4, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltrinieri, S. The feline acute phase reaction. Vet. J. 2008, 177, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsch, T.; Triebel, J.; Bollheimer, C.; Christ, M.; Sieber, C.; Fassbender, K.; Heppner, H.J. C-reaktives Protein und die Akute-Phase-Reaktion bei geriatrischen Patienten. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 48, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, C. Contribution of acute-phase reaction proteins to the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Das, S.; Mahapatra, K.D.; Saha, J.N.; Baranski, M.; Ødegård, J.; Robinson, N. Characterization of the ceruloplasmin gene and its potential role as an indirect marker for selection to Aeromonas hydrophila resistance in rohu, Labeo rohita. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, H.; Li, C.H.; Chaves-Pozo, E.; Esteban, M.Á.; Cuesta, A. Molecular identification and characterization of haptoglobin in teleosts revealed an important role on fish viral infections. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 76, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; Cao, M.; Wu, M. Expression and Functional Analysis of Hepcidin from Mandarin Fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, M.D.; Johnson, S.C.; Jones, S.R.M. Differential expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β-1, TNFα-1 and IL-8 in vaccinated pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and chum (Oncorhynchus keta) salmon juveniles. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007, 22, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.-M.; Huang, H.-Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Fu, H.-C.; Li, Z.; Fu, X.-Z.; Li, N.-Q. Characterization of mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) IL-6 and IL-6 signal transducer and the association between their SNPs and resistance to ISKNV disease. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 113, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, H.B.; Weeks, L.S.; Stratton, C.W. Evaluation of spot CAMP test for identification of group B streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1986, 24, 296–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, B.R.; Bercovier, H.; Frelier, P.F. Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus difficile 16S–23S intergenic rDNA: Genetic homogeneity and species-specific PCR. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 78, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Tibatá, V.; Junca, H.; Ariza, F.; Verjan, N.; Iregui, C. Evaluating a nested-PCR assay for detecting Streptococcus agalactiae in red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) tissue. Aquaculture 2011, 321, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Xiao, D.; Huang, J.; Fu, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, D.; Geng, Y.; Yang, T. Development of double PCR for rapid detection of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from tilapia. Chinese Vet. Sci. 2011, 41, 496–502. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Wang, K.; Xiao, D.; Liu, B.; Wan, J.; Huang, L.; Fu, X.; Wang, H. The development and application of a triple PCR method for rapid detection of Streptococcus agalactiae. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2012, 43, 254–261. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, X.; Huo, H.; Lu, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Gao, F. Development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for the rapid detection of Streptococcus agalactiae in Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2014, 45, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | GenBank Accession Number | Primer Sequence | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cp | XM_038715213.1 | F: CTACGGCGCCTATTGATGGT R: CTCTCAGCACAGGACCCATA | 174 |

| Hap | XM_038701550.1 | F: GGTCGCTGTAGAGAAGGTTGTT R: CAAGGTGTCTGCCAGGTCTT | 160 |

| Hep | XM_038710826.1 | F: CACTCGTGCTCGCCTTTATT R: TGATGTGATTTGGCATCATCCACG | 150 |

| Hx | XM_038721065.1 | F: GATGCTCCAAGTTTGGTGAGG R: TGAAGGCGTTCTCGATGGTT | 180 |

| IL-1β | XM_038733429.1 | F: TTGACATGACGGAAGTTCA R: GCTCTTCACCACTGAGCT | 168 |

| IL-6 | XM_038725465.1 | F: GGAACCCTGAACAGGTAACG R: TGTGCGGTCATCTTTCTGTGG | 100 |

| EF1α | XM_038724777.1 | F: TGCTGCTGGTGTTGGTGAGTT R: TTCTGGCTGTAAGGGGGCTC | 147 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, H.; Gao, L.; Kong, C.; Luo, S.; Zhang, S.; Ran, J.; Liu, T.; He, Y.; Wang, E. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Acute Phase Response Related Molecules in Micropterus salmoides During Streptococcus Agalactiae Infection. Fishes 2026, 11, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010012

Du H, Gao L, Kong C, Luo S, Zhang S, Ran J, Liu T, He Y, Wang E. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Acute Phase Response Related Molecules in Micropterus salmoides During Streptococcus Agalactiae Infection. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Hui, Longkun Gao, Chuizheng Kong, Siyu Luo, Shupeng Zhang, Jingjing Ran, Tianqiang Liu, Yang He, and Erlong Wang. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Acute Phase Response Related Molecules in Micropterus salmoides During Streptococcus Agalactiae Infection" Fishes 11, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010012

APA StyleDu, H., Gao, L., Kong, C., Luo, S., Zhang, S., Ran, J., Liu, T., He, Y., & Wang, E. (2026). Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Acute Phase Response Related Molecules in Micropterus salmoides During Streptococcus Agalactiae Infection. Fishes, 11(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010012