Abstract

Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846 (Placodermi: Petalichthyida), type species of Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen, 1846, was based on a single cranial roof from the Devonian of southeastern Indiana. Poor preservation, and later destruction, of the holotype has complicated subsequent studies. J.S. Newberry (1873) redefined Macropetalichthys using remains from the Devonian of Ohio. A neotype for M. rapheidolabis, from the Delaware Limestone (Middle Devonian, Eifelian) of Columbus, Ohio, is designated from Newberry’s studied specimens. The genus Agassichthys Newberry, 1857 was erected to receive two species: A. sullivanti Newberry, 1857 and A. manni Newberry, 1857. Newberry (1889) designated a lectotype for A. sullivanti from the Columbus Limestone (Middle Devonian, Eifelian) of Columbus, Ohio; once thought lost, it has been rediscovered. Agassichthys sullivanti is designated as the type species of the genus. A lectotype for A. manni Newberry, 1857, is selected from among the syntypes collected from the Delaware Limestone (Middle Devonian, Eifelian) of Delaware, Ohio. Agassichthys is a junior subjective synonym of Macropetalichthys. With a neotype of M. rapheidolabis on which to directly base taxonomic comparisons, A. sullivanti and A. manni are considered junior subjective synonyms.

Keywords:

Macropetalichthys; Agassichthys; placoderm; petalichthyid; Devonian; Ohio; Indiana; Delaware Limestone; Columbus Limestone; John Strong Newberry Key Contribution:

Difficult and confusing problems of nomenclature and stratigraphic provenance have surrounded the Devonian placoderm Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis; and they have been exacerbated by destruction of the holotype. Both nomenclatural and stratigraphic issues are resolved by designation of a neotype, one of the specimens J.S. Newberry used to redescribe the genus.

1. Introduction

Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846, a Devonian-age placoderm, or armored fish, is among the earliest described Paleozoic fishes from North America [1]. Placoderms, which evolved in the Silurian (Llandovery) and became extinct in the Late Devonian (Famennian) [2] are an early group of gnathostomes, or jawed vertebrates. They include some of the most iconic marine predators of the Devonian Period [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], the time commonly referred to as the “Age of Fishes” [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Macropetalichthys was an important component of Devonian ecosystems; it was widely distributed in shallow shelf seas of the paleocontinent Laurussia. The genus includes species recognized from North America [19,20,21] and Europe (Germany) [19,21,22,23]. Macropetalichthys is one of the most commonly cited placoderms and is a crucial reference point for understanding early gnathostome evolution. It appears not only in numerous technical publications [1,14,19,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], but also in compilations, catalogs, and general works [2,5,20,21,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], and in textbooks [16,47,48].

Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis was named from a single incomplete cranial roof (Figure 1) collected from limestone near Madison, in southeastern Indiana [1] (Figure 2). Subsequently this species, or others synonymized with it [20,21,26,28], has been reported from carbonate and mixed carbonate–fine siliciclastic lithofacies across central and eastern North America, including Ohio, Iowa, New York, and Ontario [5,15,19,20,21,24,25,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,43,44].

Fossils of Macropetalichthys have been collected from Devonian strata of the American Midwest since at least 1836 [15,25], although the earliest published records [1,24,25,26] appeared a decade or more later. Despite the frequency with which M. rapheidolabis has appeared in the literature since that time [5,15,19,20,21,24,25,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,38,43,44,45,46], central issues concerning the nomenclature, type locality, and stratigraphic occurrence of the species have remained unresolved since at least the time of Eastman [32], who in 1897 stated (p. 493): “it would not be exaggerated to assert that none of our Devonian fishes have been so completely misapprehended and erroneously described as Macropetalichthys.” The key unresolved matters can be summarized as follows:

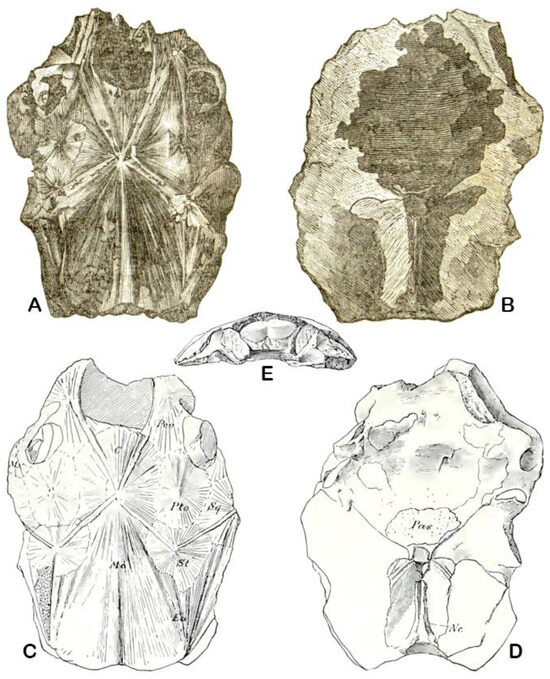

- The holotype (Figure 1), which was fragmentary and poorly preserved, was destroyed by fire [19,32] a few months after it was last studied in the 19th century [31]. Direct comparison with other species included in the genus (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) has not been possible for more than 130 years, leaving a range of nomenclatural issues, and potentially other paleobiological matters, as open questions. Although the need for a replacement name-bearing specimen has been acknowledged [49], one has not been validly designated.

- The type locality in Indiana has been uncertain. Although clues to the original site were published [1], citations of the geographic location have been imprecise. In at least one report, the type material was stated to be from the Corniferous limestone of Ohio [20].

- The lithostratigraphic and chronostratigraphic positions of the holotype have been subject to varying interpretation [19,20,23,24,33,49], and topotype specimens have never been reported. Which formation the holotype was collected from, and whether it was Lower or Middle Devonian (Emsian, Eifelian, or Givetian), has been speculative.

Two species originally assigned to Agassichthys [25] and later reassigned to Macropetalichthys [26,28] (Figure 3) were described from Devonian limestones of Ohio, and afterward illustrated material from Ohio became the primary basis for most published studies on the genus [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,32,33,35,36,37], including landmark work on the cranial anatomy [34]. However, the type specimens of Agassichthys sullivanti Newberry, 1857 and A. manni Newberry, 1857 have remained obscure, and were assumed to be lost. Without having access to the name-bearing specimens of any North American species assigned to Macropetalichthys, the nomenclature of this noteworthy fish, one of the earliest described placoderms and a model for comparison with many other placoderm taxa, has been problematic since the 1800s.

Figure 1.

Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846; illustrations of the holotype, an incomplete cranial roof, probably from the Deputy Limestone (Devonian, Eifelian) in a quarry along Lewis Creek, near Deputy, Jefferson County, Indiana (Figure 2); length about 25 cm; specimen was destroyed c. 1891 [19]. (A,B) Original woodcuts [1] (figs. 1, 2); in dorsal (A) and ventral (B) views. (C–E) Interpretive illustrations from Cope [31] (pl. 29, figs. 4,1–4,3) in dorsal (C), ventral (D), and posterior (E) views. Key to Cope’s [31] interpretation of cranial bones: C, central; Eo, exoccipital; Mo, median occipital; Mx, maxillary or malar; Nc, nuchal canal; Pas, parasphenoid; Peo, preorbital; Pto, postorbital; Sq, squamosal; St, supratemporal.

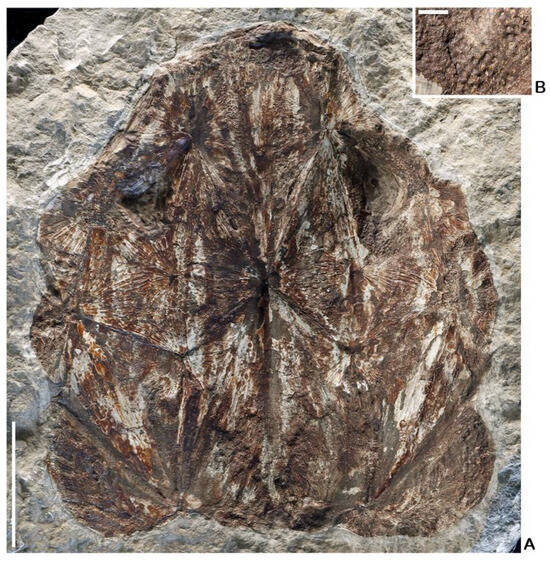

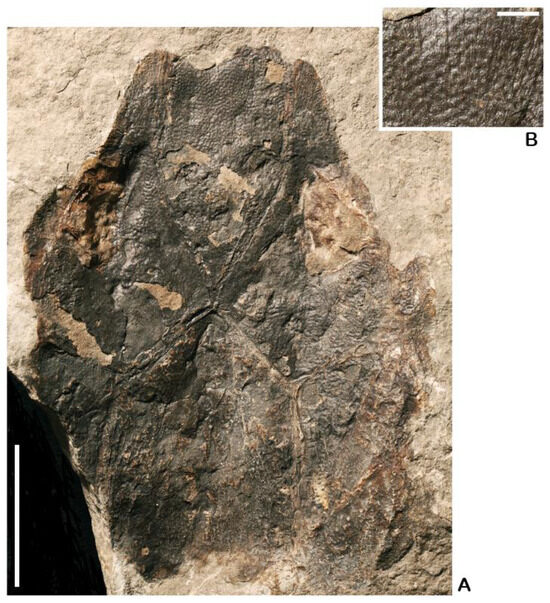

To clarify and stabilize the nomenclature of Macropetalichthys, and to clarify the type locality of the type species, a neotype for M. rapheidolabis (Figure 4) is designated here. The need for an accessible name-bearing type specimen, one preserving details sufficient for recognizing the species, is exceptional. Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis is the type species of the genus-group taxon Macropetalichthys, and Macropetalichthys is in turn the type genus of the family-group taxon Macropetalichthyidae [21]. Multiple species have been referred at one time or another to Macropetalichthys [19,21,22,23,33], and differentiating them from the type species of the genus necessitates having an unambiguous basis for comparison, meaning a name-bearing type showing characters useful for diagnosis. Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis is one of the most often cited placoderms [1,2,5,14,15,16,19,20,21,24,25,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]; its cranial anatomy [34,37] is one of several models central to phylogenetic studies of the group. The single specimen used in the original description of M. rapheidolabis [1] no longer exists; it was destroyed by fire at the University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, c. 1891 [19]. Topotype specimens of M. rapheidolabis are not known, and neither the original type locality nor horizon are known with certainty, although as discussed herein, a likely location and stratigraphic position have been identified (Figure 2). The now-destroyed holotype was derived from what was once termed the “Cliff Limestone” [24], and more specifically the “Corniferous limestone” [26,28] of southeastern Indiana, in strata deemed equivalent to the “Corniferous limestone” of Ohio [24,26]. Designation of a neotype from among the earliest specimens collected from the “Corniferous” of central Ohio represents a choice as close as practicable to the original horizon and lithofacies. Moreover, this specimen derives from the hypodigm used in diagnosis of the species Agassichthys sullivanti [25], a junior synonym of M. rapheidolabis (as first suggested by Newberry [28]), and applied in Newberry’s rediagnosis of the genus Macropetalichthys [28]. Once A. sullivanti became broadly recognized as a junior synonym of M. rapheidolabis [19,20,21,33,43,44], Newberry’s descriptions of the species [25,28] formed the taxonomic basis of M. rapheidolabis that most subsequent authors have followed. Based on available woodcut and line-drawing illustrations (reproduced here in Figure 1), the neotype (Figure 4) agrees in general proportions, and in the configurations of observable cranial plates, with the holotype. Importantly for species identification, both the holotype and the neotype share double rows of large sensory canal pores. The dermal bones of the neotype are ornamented with densely spaced, stellate tubercles, which help to diagnose the species. The neotype is reposited in the Orton Geological Museum at The Ohio State University (OSU 14189).

The neotype of M. rapheidolabis is derived from the original set of specimens leading to Newberry’s [28] redescription of the genus Macropetalichthys, which has been the basis for most subsequent systematic and other paleobiologic work on this taxon. All of Newberry’s specimens were collected from either the Columbus Limestone or the Delaware Limestone (Devonian) of Ohio (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). In accordance with Articles 23 and 75.6 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature [50] (hereinafter referred to as the “Code”), this act conserves the species-group name M. rapheidolabis, which has priority over the synonyms Agassichthys sullivanti and A. manni, in its prevailing usage. Any reversal of precedence or change in meaning, if an issue of taxonomic discord were to be discovered, would risk introducing serious confusion to the literature. The genus-group name Macropetalichthys, which is also in prevailing usage following Newberry [26,28], and has priority over Agassichthys, is also conserved.

Germane to the stabilization of the Macropetalichthys nomenclature, the rediscovered lectotype of A. sullivanti (Figure 5) is reported here, and a lectotype for A. manni (Figure 6), selected from the original syntypic suite, is designated. The name-bearing specimens of M. rapheidolabis, A. sullivanti, and A. manni are illustrated photographically for the first time. Agassichthys sullivanti is designated as the type species of Agassichthys, and the genus is treated as a junior subjective synonym of Macropetalichthys.

By designating a neotype for M. rapheidolabis, the most important nomenclatural issue pertaining to Macropetalichthys is resolved, as the definition of the type species is now fixed, and direct comparisons with other named species are possible. Designating a neotype for the species from an unambiguous and well-known locality and stratigraphic horizon also resolves the issue of type locality, as the type locality is determined by the neotype (Article 76.3 of the Code [50]).

2. Materials and Methods

The specimens illustrated in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 are reposited in the Orton Geological Museum at The Ohio State University (OSU), Columbus, Ohio. One specimen (OSU 14189; Figure 4), from the J.S. Newberry collection [51], has been in the OSU collection since the 1870s. Another specimen (OSU 54765; Figure 6) was originally from the R.P. Mann cabinet of minerals, rocks, and fossils [38,52] and had been reposited in the geological collection of Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU), Delaware, Ohio, around 1860, until its transfer to the OSU collection in 2024. Another specimen (OSU 1816; Figure 5) apparently was originally placed in the collection of Marietta College (MC) in 1836 [15] and transferred to the OSU collection in approximately 1874.

The specimens were photographed with a Canon EOS R6 Mark II camera (Tokyo, Japan). The images were assembled in Adobe Photoshop.

3. Nomenclatural and Stratigraphic History of Macropetalichthys

3.1. Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis from Indiana

Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846 was described from a single incomplete head shield (Figure 1) collected from Devonian limestone in a quarry in the proximity of Lewis Creek, a branch of the Muscatatac (alternatively spelled “Muskatatac” [1]) River, approximately 24 km northwest of Madison, Jefferson County, Indiana [1] (p. 367). The stratigraphic position of the specimen is somewhat ambiguous and has been the subject of various interpretations. Newberry [24] stated that it was derived from the “Cliff Limestone.” Norwood and Owen noted that they relocated a natural mold of the fossil in outcrop. It was in a light grey limestone layer, which on Lewis Creek was “not four feet” (1.3 m) below a black shale (referred to as “black slate”) [1] (p. 370). They stated that the limestone contained brachiopods, bivalves, corals, trilobites, tentaculitids, and other fossils that they correlated with the Onondaga and Hamilton groups (Devonian) of New York. It is uncertain whether all these fossils were from the same layer as the fish or, more likely, were representative of the ~8.5 m limestone succession, comprising four formations, at the inferred site.

Ludlum [49] provided a cogent discussion of the likely provenance of Norwood and Owen’s specimen [1]. The quarry from which it was collected may be the same one that Campbell [53] described on Lewis Creek, along a secondary road (W. Blake Road), 0.8 km east of the intersection with Highway 3, about 1.4 km south of the center of Deputy, Jefferson County, Indiana, 38.78′ N, 85.64′ W (Figure 2). At this site, the New Albany Shale (Devonian–Carboniferous), a black shale, overlies a Devonian limestone succession that includes, in ascending order, the Jeffersonville Limestone (at least 3.1 m thick), Speeds Limestone (3.3 m thick), Deputy Limestone (2 m thick; the type section), and Swanville Limestone (17 cm thick) [53]. If this is the correct site, the placoderm fossil was probably found near the middle of the Deputy Limestone. Campbell [53] reported the brachiopods Muscrospirifer mucronatus (as “Spirifer” mucronatus) and Cyrtina hamiltonensis from the Deputy Limestone, which suggests a correlation with the Hamilton Group of New York and a Givetian age.

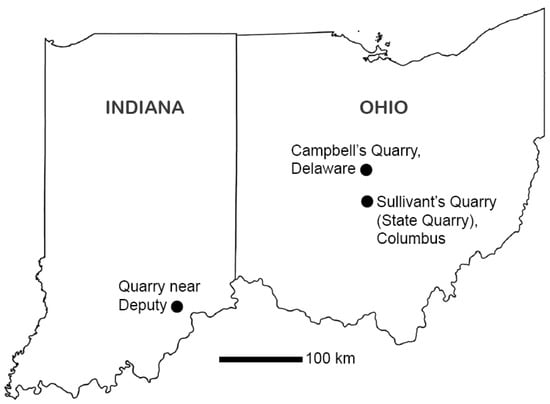

Figure 2.

Map of Ohio and Indiana, USA, showing locations of Devonian limestone quarries yielding type specimens of Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis, including junior synonyms. The holotype, which was destroyed, may have been collected from the Deputy Limestone in a quarry near Deputy, Indiana (inferred to be 38.78′ N, 85.64′ W). The neotype of M. rapheidolabis was collected from the lower Delaware Limestone in Sullivant’s Quarry (State Quarry), Columbus, Ohio (39.96′ N, 83.05′ W); and the lectotype of Agassichthys sullivanti was collected from the Columbus Limestone in the same quarry. The holotype of A. manni was collected from the lower Delaware Limestone in Campbell’s Quarry, Delaware, Ohio (40.30′ N, 83.08′ W). Base map from https://gisgeography.com/.

The holotype of M. rapheidolabis (Figure 1) has been described in starkly different terms by different authors [1,15,31]. Norwood and Owen [1] (p. 367) remarked that the fossil “had suffered greatly from thoughtless mutilation, while in the hands of the quarryman, which renders it difficult to give a satisfactory description …” Later, Newberry [26] indicated that he had examined a plaster cast of the specimen. In an 1889 paper, Newberry [15] (p. 41) stated that the “The generic description given by Drs. Norwood and Owen was very defective from the imperfections of the specimen which served as the type.” In contrast, Cope [31] (p. 449), who was the last person to report studying the holotype of M. rapheidolabis, stated that the specimen “remains one of the best for the elucidation of the type of fishes which it represents, although it is imperfect. It has the advantage of having lost most of the surface of the cranial ossification, so that its true structure is the more easily determined.” Cope [31] described the specimen in detail over the space of several published pages.

3.2. Macropetalichthys manni and M. sullivanti from Ohio

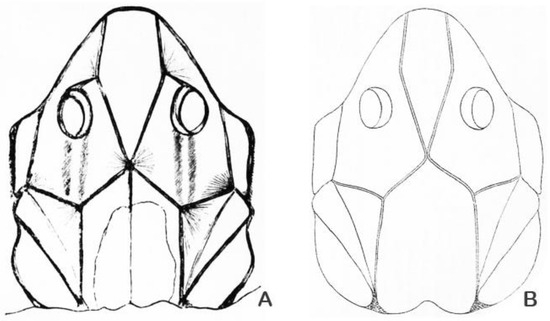

In 1853, J.S. Newberry illustrated remains of two genera of “ganoid” fishes collected from the “Cliff limestone” of Ohio (Devonian) [24]. One woodcut was a composite illustration of the cranial roof of a placoderm [24] (fig. 1), reproduced here as Figure 3A. The other woodcut, also a composite figure, illustrated two parasymphysial teeth of a sarcopterygian later named Onychodus sigmoides Newberry, 1857 [25,38]. Newberry [25] hinted that the cranial elements and the teeth belonged to the same species of fish, but by 1857 described these phosphatic elements under different, and new, genus-group names: Onychodus for the teeth [38], and Agassichthys for the cranial roofs [25]. Agassichthys, the placoderm, received two new species: A. manni and A. sullivanti. A new reconstruction, similar to that published in 1853 but with some different details, accompanied the description of A. manni [25] (text fig. p. 123); it is reproduced here as Figure 3B. Agassichthys sullivanti was not illustrated, nor was a type specimen specifically identified. A principal distinction between the two species was size: The crania of A. manni ranged in length from about 15 to 23 cm, whereas the crania of A. sullivanti ranged from about 25 to 30 cm. The shorter crania, which were referred to A. manni, were also narrower in absolute width than the longer crania, which were referred to A. sullivanti.

Figure 3.

Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846. (A) Original woodcut of a “ganoid fish,” a composite based on specimens from the “Cliff Limestone” (Devonian) of Ohio; from Newberry [24] (fig. 1). (B) Original illustration of Agassichthys manni Newberry, 1857 [25] (text fig. p. 123); a composite based on specimens from the “Cliff Limestone” (Devonian) of Ohio.

Newberry described Agassichthys manni and other Devonian fishes from specimens apparently in or subsequently reposited with Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware, Ohio [25]. He stated (p. 120) “… Prof. F. Merrick has had the kindness to send me for examination a collection of unusually fine ichthyolites, from the Cliff limestone of Delaware, Ohio; and I am indebted for similar favors to … Dr. R.P. Mann, of Milford, Ohio.” Frederick Merrick at the time was president of Ohio Wesleyan, and Reuben P. Mann later deposited much of his geological collection with the university [38,52]. The best indication of specimens examined by Newberry leading to later description as A. manni comes from Newberry’s 1853 paper: at least two specimens were used to draft the composite illustration [24] (fig. 1; reproduced herein as Figure 3A). According to Newberry [24] (p. 12), the lengths of those two examined crania were 9 inches (23 cm) and 6 inches (15 cm), and they retained some of the dermal armor, which had stellate tubercles. The composite figure was redrafted and published in 1857, possibly with the addition of information from other specimens, as the illustration accompanying the original description of A. manni [25] (text fig. p. 123; reproduced herein as Figure 3B). It was published again in 1873 [28] (text fig. p. 294) and 1874 [29], with notation on interpretation of the cranial plates, as Macropetalichthys.

In 1889, Newberry [15] (p. 27) identified one specimen from the original suite referred to A. sullivanti as a “type,” stating: “The remains of fishes in the Corniferous limestone early attracted attention. Mr. Joseph Sullivant, of Columbus, Ohio, was probably the first to notice and collect them, but he did not attempt to describe them. As early as 1836 he presented a cranium, which he obtained in his quarries at Columbus, to Marietta College, Ohio, and I subsequently made this the type of Macropetalichthys Sullivanti as a recognition of the value of his contributions to geology.” The cranium that Sullivant presented to Marietta College must be considered the lectotype of A. sullivanti, in accordance with Article 74 of the Code [50]. Joseph Sullivant’s Devonian fish material from limestones in the quarry that his brother William S. Sullivant owned (later called the State Quarry [54]) along the Scioto River near (now within) Columbus, Ohio [15,26], is one of the earliest recognized paleontological collections from Ohio. The whereabouts of the lectotype of A. sullivanti has remained unknown since the late 1800s.

By 1862, Newberry [26] recognized that Agassichthys was synonymous with Macropetalichthys, and he recombined the two 1857 species as M. manni and M. sullivanti. In his 1862 paper, Newberry [26] recognized a total of four Devonian species in Macropetalichthys: M. manni and M. sullivanti from Ohio, M. rapheidolabis from Indiana, and M. agassizii from Germany.

Newberry published the first illustrations of M. sullivanti in 1873 [28] (pl. 24, pl. 25, figs. 1, 1a), but the lectotype was not among the illustrated specimens. At that time, he also indicated the possibility that M. manni may be a synonym of M. sullivanti but did not include M. manni in the synonymy list of M. sullivanti. Rather, he stated in text that he was “disposed to consider the differences which they exhibit as probably due to age or sex. Further observation may prove these forms to be specifically distinct; for the present it is perhaps wiser to consider all of our specimens as varieties of M. sullivanti.” Eastman [32] noted that the holotype of M. rapheidolabis had been destroyed years earlier but also indicated (p. 498) a “marked difference” between M. rapheidolabis and M. sullivanti in the outline of the maxillary plate, assuming the shape was correctly interpreted. Later, Eastman [33] synonymized all described species of Macropetalichthys from North America, stating (p. 168): “This genus … was first described under the name of M. rapheidolabis. Subsequently, two new specific titles, M. sullivanti and M. manni, were proposed by Newberry for cranial shields that presented no important differences from the type, and it was afterwards proved that no constant distinctive features exist.”.

From the 1920s, authors have consistently interpreted M. rapheidolabis and M. sullivanti to be synonyms [20,34,35,45], without the benefit of any known name-bearing specimens on which to base comparisons, and only vague knowledge of the stratigraphic occurrences of the type specimens. This contrasts with E.D. Cope’s 1891 assessment [31]. Cope was the last person to have studied both the holotype of M. rapheidolabis and at least one specimen of M. sullivanti from the Newberry collection. The specimen from Newberry’s collection was loaned by Edward Orton. Cope [31] relied largely on cranial dimensions to distinguish M. sullivanti from M. rapheidolabis. The specimen designated herein as the neotype of M. rapheidolabis (Figure 4) corresponds closely to Cope’s concept of this species, and serves as the basis for the comparative analysis here in the Systematic Paleontology section (Section 4). Designation of a neotype will facilitate future comparative studies.

3.3. The “Cliff Limestone”

Originally, North American fossils of Macropetalichthys [1,24] and Agassichthys [24,25] were assigned stratigraphically to what was described in the 1830s–1850s as the “Cliff limestone” (alternatively, “Cliff Limestone”). The term, as explained by Newberry [14] (pp. 142–145), owes its origin to the first Geological Survey of Ohio, which operated in 1837–1838 under the direction of William W. Mather [55]. Surficially exposed rocks of western Ohio, on the eastern side of the Cincinnati Arch, were divided into two “limestone groups”: the “Blue limestone series” and the superjacent “Cliff limestone.” The “Blue limestone series” was termed the “Cincinnati Group” in publications of the second Geological Survey of Ohio, under the direction of John Strong Newberry, 1869–1882, and then Edward Orton, 1882–1888. According to Newberry [13,14], the Cincinnati Group was originally assigned to the Lower Silurian stratigraphically, as it was not until 1879 that Lapworth [56] defined the Ordovician System, to which it is now assigned. The “Cliff limestone” included units termed Clinton, Niagara, Waterlime, Corniferous, and Hamilton, ranging from what was considered “Upper Silurian” to Devonian in publications of the second Geological Survey of Ohio. By current standards, these units range from mid-Silurian (Wenlock) to Middle Devonian (Givetian) [57].

In 1862, Newberry [26] identified the Corniferous as the unit from which Agassichthys (=Macropetalichthys) material was collected in Ohio. In central and northern Ohio, Newberry [14] divided the Corniferous into two units, which he termed “Columbus limestone” (lower) and “Sandusky limestone” (above). Stewart [58] summarized the evolution of stratigraphic nomenclature for the Middle Devonian of Ohio up to the 1950s. Newberry’s “Sandusky limestone” included what Orton [30] termed the Delaware Limestone plus the upper part of the Columbus Limestone (as restricted). As usually recognized, the upper limit of the Columbus Limestone is considered to be at the top of the second bone bed [58,59,60] in the “Corniferous” sequence of earlier usage, and most of the former “Sandusky limestone” is now considered to be Delaware Limestone [30,38,58,61,62,63,64,65]. In places, the Tioga B K-bentonite layer overlies the second bone bed and helps mark the contact between the Columbus and Delaware limestones [38,66]. The bentonite has yielded a radiometric age of 390 ± 0.05 Ma [66].

The term “Cliff limestone” was also applied on the western side of the Cincinnati Arch [24]. In Indiana, the part corresponding to the “Corniferous” included at least six formations, Jeffersonville through Beechwood [53].

3.4. Rediscovery and Designation of Type Specimens

The holotype of Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846 is known to have been destroyed [19,32], and to date a replacement name-bearing specimen has not been designated. In the interest of stabilizing the nomenclature of this placoderm genus, a neotype of M. rapheidolabis (Figure 4) is designated here, in accordance with Article 75 of the Code [50]. A name-bearing type is necessary to define the type species of the genus objectively and to distinguish it from other species included in Macropetalichthys, either currently [19,20,21,22,23] or previously [67,68]. By providing a solution to competing interpretations of M. rapheidolabis [15,31,33], this act provides a solution to the complex nomenclatural problems surrounding Macropetalichthys and Agassichthys, and M. rapheidolabis, A. sullivanti, and A. manni. The best available option for selection of a neotype is a specimen from Newberry’s material from Ohio, a specimen which Newberry used in redefining Macropetalichthys.

Newberry did not designate a type specimen for A. manni, nor did he designate a type species for Agassizichthys. He did, however, select a lectotype for A. sullivanti [15]. Much of the Macropetalichthys (including Agassichthys) material that Newberry examined between about 1853 and 1873, and used for his formulation of species and generic descriptions, was reposited in the OSU and OWU collections. Specimens quarried from Columbus, Ohio, predominate among the early additions to the OSU collection, and ones quarried from Delaware, Ohio, predominate in the original OWU collection. One specimen from Columbus was originally deposited in the MC collection. Three of Newberry’s studied specimens are either recognized here as type material after rediscovery, or designated here as name-bearing:

- OSU 14189 (Figure 4), designated here as the neotype of Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846. This is an essentially complete cranial roof, 22.2 cm in length, and appearing relatively wide due to moderate taphonomic compaction, on a large block of limestone. The specimen is viewed from the inside of the cranial roof, so it is concave. The basal layer of bone is mostly broken away, revealing the middle layer over much of the specimen. The middle bone layer contains coarse vascular canals separated from each other by slender bony trabeculae. The trabeculae radiate from the centers of individual bones toward their margins. A weak medial ridge is present on the nuchal bone. Small patches of the outer layer of bone, showing densely spaced, stellate tubercles, are exposed near both orbits, with the larger patch surrounding the left orbit, especially on the postorbital, marginal, and medianorbital bones (Figure 4A, right side, Figure 4B). The specimen was highlighted with brown paint at some point in the past. Where bone shows through the paint, it is blue-grey in color.

The neotype was collected from William S. Sullivant’s quarry, along the west bank of the Scioto River in Columbus, Franklin County, Ohio (39.96′ N, 83.05′ W). This quarry was sold to the State of Ohio in 1845 and became known as the State Quarry [54]. The specimen clearly derives from the interval termed “Sandusky limestone” by Newberry [14]. Relatively fresh broken surfaces on the underside of the slab show the matrix to be a slightly bluish, medium-grey limestone, weathering tan. A white spot, possibly a cross-section of a Planolites trace fossil, and an incomplete spiriferid brachiopod, probably Mucrospirifer mucronatus, are on the back of the slab. The lithology and associated brachiopod are consistent with the lower part of the Delaware Limestone (Middle Devonian, Eifelian). This horizon corresponds to the Delaware Limestone “fish bed” Lagerstätte [38], a concentration-type fossil deposit, or Konzentrat-Lagerstätte [69,70].

Figure 4.

Neotype (designated here) of Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846; from the “Sandusky limestone” of Newberry [14], lower Delaware Limestone (Devonian, Eifelian), Sullivant’s Quarry, Columbus, Ohio (Figure 2); interior view of cranial roof showing moderate relief (expressed as concavity); in most places the middle layer of bone, with radiating trabeculae on the plates, is evident; OSU 14189. (A) View of entire specimen; bar scale = 5 cm; (B) magnified view of area behind left orbit (upper right side of photograph (A)), showing densely spaced, stellate tubercles; bar scale = 5 mm.

- 2.

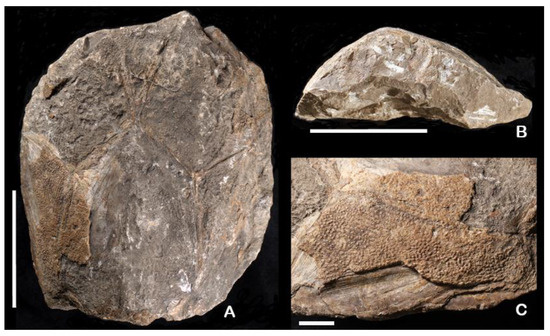

- OSU 1816 (Figure 5), the lectotype of Agassichthys sullivanti Newberry, 1857, by subsequent designation [15] (p. 27). This is an incomplete cranial roof viewed from the internal side, compacted but still moderately concave, missing pieces around the margins, and deeply weathered in places, 19.8 cm in length, preserved on a large block of limestone. Some of the outer layer of bone remains, especially in the anterior part, where densely arranged, stellate tubercles are evident and seemingly relatively unweathered (Figure 5B). Elsewhere, portions of the middle layer of bone are showing. The specimen was highlighted with brown or black paint and apparently coated with a thin layer of shellac, which has further darkened the specimen. Examination under shortwave ultraviolet light reveals glue spots where two labels apparently were once attached to the surface of the specimen. Newberry commonly glued large labels to his type specimens of fishes, indicating his identification and type status. OSU 1816 seems to be the specimen that Joseph Sullivant presented to Marietta College in 1836. It has been part of the OSU collection since about 1874.

Figure 5.

Lectotype of Agassichthys sullivanti Newberry, 1857, designated by Newberry [15] (p. 27), a junior subjective synonym of Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846; from the “Sandusky limestone” of Newberry [14], upper Columbus Limestone (Devonian, Eifelian), Sullivant’s Quarry, Columbus, Ohio (Figure 2); interior view of compacted cranial roof, incomplete at the margins; OSU 1816. (A) View of entire specimen; bar scale = 5 cm; (B) magnified view near anterior end, showing densely spaced, stellate tubercles; bar scale = 5 mm.

The specimen was collected from William S. Sullivant’s quarry, along the Scioto River in Columbus, Ohio, the same quarry that yielded the neotype (OSU 14189). The specimen probably derives from the interval termed “Sandusky limestone” by Newberry [14]. Relatively fresh broken surfaces on the underside of the slab show the matrix to be a light grey limestone. The lithology and associated fauna are consistent with the uppermost part of the Columbus Limestone (Middle Devonian, Eifelian). A strophomenid brachiopod, Stropheodonta perplana, which is characteristic of the Columbus Limestone [64] is on the upper surface of the slab, close to the fish. Numerous pelmatozoan echinoderm ossicles, probably comprising blastoids and crinoids, are present on the undersurface of the slab. Ausich [71] documented the blastoids Eleacrinus verneuili and Heteroschisma pyramidatus, and the crinoid Dolatocrinus lacus, from the Columbus Limestone but they cannot be identified from separated ossicles.

- 3.

- OSU 54765 (Figure 6), a syntype of Agassichthys manni Newberry, 1857, is designated here as the lectotype, in accordance with Article 74 of the Code [50]. It is a convex, incomplete cranial roof specimen, missing much of the anterior and lateral areas, highly weathered and largely exfoliated, 14.5 cm in length, and free of limestone matrix except on the underside. A small patch of the outer layer of bone remains on the left paranuchal (Figure 6C); although weathered, it shows densely arranged, stellate tubercles. OSU 54765 is broken at the cranial–thoracic joint, roughly along bone surfaces (Figure 6A,B). The break closely resembles the break indicated at the posterior of the cranium in Newberry’s 1853 figure [24] (fig. 1; herein Figure 3A). In addition, Newberry’s figure shows an irregular weathered area on what he [15] termed the supra-occipital bone (nuchal bone and adjacent, paired posterior paranuchal bones). An exfoliated, weathered area of similar outline and location is present on OSU 54765. This specimen, which was previously in the OWU collection, appears to be one of the models for the composite figure of a “ganoid fish” [24] (fig. 1; herein, Figure 3A) and A. manni [25] (text fig. p. 123; herein, Figure 3B). The upper surface of the specimen (Figure 6A) was darkened using dark brown or black paint or ink.

Figure 6.

Lectotype (designated here) of Agassichthys manni Newberry, 1857, a junior subjective synonym of Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846; from the lower Delaware Limestone (Devonian), Campbell’s Quarry, Delaware, Ohio (Figure 2); OSU 54765. (A) Dorsal view of incomplete, weathered, and largely exfoliated cranial roof, missing much of the anterior and lateral parts; bar scale = 5 cm; (B) posterior view showing strong convexity of the cranial roof and bones at the cranial–thoracic joint; bar scale = 5 cm; (C) outer surface of left paranuchal bone showing densely spaced tubercles; although weathered, some tubercles retain a stellate appearance; bar scale = 5 mm.

As discussed by Babcock [38], many of Newberry’s type specimens of Devonian fishes that were reposited in the OWU collection were collected from the “fish beds,” a Fossil-Lagerstätte in the lower part of the Delaware Limestone (Devonian, Eifelian) at Campbell’s Quarry, now Blue Limestone Park, in Delaware, Delaware County, Ohio. This interval corresponds to part of the “Sandusky limestone” of Newberry [14]. OSU 54765 is inferred to have been collected from this horizon and locality. On the relatively fresh broken surface at the posterior of the cranium, the limestone matrix is brownish grey, similar to the color of limestone enclosing the lectotype of Onychodus sigmoides [38], which is from the same locality. On the weathered underside of the specimen the limestone matrix is tan. The underside of this specimen shows numerous pelmatozoan ossicles, and this is characteristic of the “Sandusky limestone” interval of Newberry [14]. Together, these sedimentary indicators are consistent with the interval in the lower Delaware Limestone that DeSantis et al. [72] informally referred to as the “Stratford member”.

4. Systematic Paleontology (Following [21])

Class Placodermi M’Coy, 1848 [73]

Order Petalichthyida Jaekel, 1911 [74]

Family Macropetalichthyidae Eastman, 1898 [75]

Genus: Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen, 1846

- 1846

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen, p. 371 (original description).

- 1857

- Agassichthys–Newberry, pp. 120–122 (original description).

- 1862

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Newberry, pp. 75–76.

- 1873a

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Newberry, p. 145.

- 1873b

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Newberry, pp. 264–265, 290–294, text fig. p. 294.

- 1874

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Newberry, pp. 288–292, text fig. p. 292.

- 1891

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Cope, pp. 449–456.

- 1889

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Newberry, pp. 41–44, text fig. 2.

- 1889

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Miller, p. 601.

- 1907

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Eastman, pp. 100–103.

- 1908

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Eastman, p. 168.

- 1978

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Denison, pp. 39–40 (see for additional synonymy).

- 1963

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Van Valen, pp. 257–261.

- 2015

- Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen–Pan, Zhu, Zhu, and Jia, pp. 130, 133, fig. 9.

Type species: Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846 (by monotypy [1]).

Diagnosis: Petalichthyid fish with cranial roof that is widest just behind orbits, narrowing slightly posteriorly and narrowing rapidly anteriorly to a broad, blunt snout. Rostral and pineal fused, forming a rostro-pineal bone, meeting the nuchal at posterior; preorbitals separated. Orbits small, located behind inferred position of pineal organ. Sensory canals broad, with single or double row of pores; supraorbital canals meet the posterior pit lines, forming a distinct angle in midline of the nuchal. Neurocranium is a single perichondral ossification except for unossified nasal capsules; supravagal processes prominent, located at posterior end of occipital region, in front of craniospinal processes. Dermal bones ornamented with tubercles, arranged irregularly or concentrically. Presence of trunk shield implied by longitudinally arranged glenoid fossae on ventral faces of posterior paranuchals.

Remarks: The diagnosis is modified slightly from Denison [21], who also listed included species from the Devonian of North America and Germany and listed presumed synonymous genus-group names. The term “supravagal process” is used here in the sense of Stensiö [76], Denison [21], and Pan et al. [77]. The large supravagal processes of Macropetalichthys lie anterior to the craniospinal processes [77] (fig. 7E).

Agassizichthys sullivanti Newberry, 1857 [25] is here designated as the type species of Agassizichthys Newberry, 1857 [25]. Agassizichthys is regarded as a junior subjective synonym of Macropetalichthys Norwood and Owen, 1846.

Denison [21] noted that spinals referred to as Acanthaspis, and other plates of the dermal shield of the trunk, probably belong to Macropetalichthys. This possible synonymy of genus-group names, however, does not affect the family-group nomenclature, according to Article 35.5 of the Code [50], even though the family name Acanthaspidae Woodward, 1871 [78] has priority over the family name Macropetalichthyidae Eastman, 1898 [75]. Macropetalichthyidae is the genus-group name in prevailing usage [19,20,21,33], so it should be conserved. Spinals referrable to Acanthaspis in direct association with a cranial roof referrable to Macropetalichthys are not known at present, and resolution of the family-group matter awaits further, more informative discoveries.

- 1846

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis–Norwood and Owen, pp. 367–371, figs. 1, 2 (original description).

- 1846

- Pterichthys norwoodensis–Owen in Norwood and Owen, p. 371 (original description).

- 1853

- Ganoid fish–Newberry, pp. 12–13, fig. 1.

- 1853

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Newberry, p. 13.

- 1857

- Agassichthys manni–Newberry, pp. 122–123, text fig. p. 123 (original description).

- 1857

- Agassichthys sullivanti–Newberry, pp. 123–124 (original description).

- 1862

- Macropetalichthys manni (Newberry)–Newberry, p. 76, text fig. p. 75.

- 1862

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Newberry, p. 76.

- 1862

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Newberry, p. 76.

- 1871b

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Newberry, p. 18.

- 1873a

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Newberry, pp. 142–143.

- 1873b

- Macropetalichthys manni (Newberry)–Newberry, p. 265.

- 1873b

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Newberry, pp. 265, 267, 294–296, pl. 24, pl. 25, figs. 1, 1a.

- 1873b

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Newberry, p. 267.

- 1874

- Macropetalichthys manni (Newberry)–Newberry, p. 265.

- 1874

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Newberry, pp. 264, 267, 292–294, pl. 24, pl. 25, figs. 1, 1a.

- 1874

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Newberry, p. 267.

- 1878

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Orton, pp. 625, 628.

- 1889

- Macropetalichthys manni (Newberry)–Newberry, pp. 27, 44, pl. 38, figs. 1, 2, 2a.

- 1889

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Lesley, p. 376, fig.

- 1889

- Macropetalichthys manni (Newberry)–Miller, p. 601.

- 1889

- Pterichthys norwoodensis Owen in Norwood and Owen–Miller, p. 610.

- 1889

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Miller, p. 601, fig. 1146.

- 1889

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Miller, p. 601.

- 1891

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Cope, pp. 449–456, pl. 29, fig. 4,1–3.

- 1891

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Cope, p. 453–456, p. 30, fig. 5,1–3.

- 1892

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Lesley, fig. p. 1160.

- 1897

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Eastman, pp. 493, 499, pl. 12.

- 1897

- Macropetalichthys sullivanti (Newberry)–Eastman, pp. 493, 499, pl. 12.

- 1902

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Hay, p. 349.

- 1907

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Eastman, pp. 14, 103–112, pl. 9, fig. 5, pl. 11, text figs. 19–21.

- 1907

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Hennig, p. 587.

- 1908

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Eastman, pp. 168–175, text-fig. 24.

- 1908

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Hussakof, p. 16.

- 1918

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Hussakof and Bryant, pp. 25–26.

- 1925

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Stensiö, p. 89, pls. 19–28, 30, figs. 1–13, 15.

- 1926

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Jaekel, pp. 161–184, figs. 1–3.

- 1929

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Hay, p. 644.

- 1957

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Ørvig, p. 294, figs. 5A, 7B.

- 1963

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Van Valen, text-fig. 1E.

- 1966

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Gardiner, pp. 36–38 (see for additional synonymy).

- 1996

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Hansen, p. 289, fig. 21-1.4, 21-1.5.

- 2015

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Pan, Zhu, Zhu, and Jia, p. 128, fig. 7E.

- 2025a

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Babcock, pp. 4, 6.

- 2025

- Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen–Babcock et al., fig. 3B.

Neotype (designated here): Articulated bones of the cranial roof, OSU 14189 (Figure 4), from the lower Delaware Limestone (Middle Devonian, Eifelian), Sullivant’s Quarry (later called the State Quarry), west bank of the Scioto River, Columbus, Franklin County, Ohio, USA (now the type locality of M. rapheidolabis, according to Article 76.3 of the Code [50]).

Types of junior subjective synonyms: Lectotype of Agassichthys sullivanti Newberry, 1857, designated by Newberry [15], incomplete cranial roof, OSU 1816 (Figure 5); from the Columbus Limestone, probably the upper part (Middle Devonian, Eifelian), Sullivant’s Quarry, along the west bank of the Scioto River, Columbus, OH, USA. Lectotype of Agassichthys manni Newberry, 1857 (designated here), incomplete cranial roof, originally from the OWU collection, OSU 54765 (Figure 6); from the Delaware Limestone (Middle Devonian, Eifelian), Campbell’s Quarry (now Blue Limestone Park), Delaware, Delaware County, OH, USA.

Diagnosis: Macropetalichthys reaching large size; having rostro-pineal with spatulate outline, widest behind midpoint, narrowing anteriorly, angulate at posterior; sensory canal pores large for the genus, forming double rows; weak medial ridge on nuchal; dermal bones ornamented with stellate tubercles, densely spaced.

Remarks: As rediagnosed here, only one valid species of Macropetalichthys, M. rapheidolabis Norwood and Owen, 1846, is recognized from North America at the present time. This opinion hinges on stabilization of the species definition with a neotype, OSU 14189, from the Delaware Limestone “fish bed” Lagerstätte of Columbus, Ohio. Whether Norwood and Owen’s [1] petalichthyid specimen from the Deputy Limestone (presumably) of southeastern Indiana is truly conspecific is an untested assumption. The holotype cranial roof, which has been destroyed, was poorly preserved, but based on Cope’s [31] description and interpretative drawing (reproduced herein, Figure 1C), the specimen designated as the neotype resembles it in general proportions and dermal bone configurations. Both the destroyed holotype and the neotype have a double row of large sensory pores. It is not known whether the holotype had stellate tubercles on the dermal bones similar to those shown on the neotype. In any case, designation of a neotype stabilizes the species-group name M. rapheidolabis with one of the specimens on which Newberry’s [28] redescription of the species was based, and in line with prevailing usage. Perceived differences in cranial length among the type specimens of M. rapheidolabis, M. sullivanti, and M. manni (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) are attributed to intraspecific variation, including age and possible sexual dimorphism. Differences in proportional width of specimens, as preserved, seem to be largely taphonomic in origin, related to the amount of compression of cranial elements. The shapes and configurations of cranial dermal plates, to the extent that they can be discerned from specimens variously revealing the upper and middle bony layers, seem consistent across specimens representative of the three named species. Significant differences in the pattern of tuberculation on the dermal armor among Newberry’s examined specimens and the numerous published examples are not apparent.

In a note added to the paper by Norwood and Owen [1] (p. 371), D.D. Owen unintentionally introduced a second name for the holotype of M. rapheidolabis. An indication that the term, Pterichthys norwoodensis, applies to the same specimen described in the main text means that it satisfies the requirement for publication according to Article 12 of the Code [50]. The name was not clearly indicated as a junior synonym upon first publication, and Miller [40] used the name in a later publication as an available name. The name is a junior objective synonym of M. rapheidolabis.

Two species assigned to Macropetalichthys are known from the Middle Devonian of Germany and were discussed by both Eastman [33] and Denison [21]. Macropetalichthys agassizi von Meyer, 1846 [79] is a medium-size species that has sensory canals in a single row, in contrast to the double row present in M. rapheidolabis. It also has a distinct, sharp medial ridge. extending the length of the rostro-pineal bone on the external surface [79] (pl. 12, fig. 1.a, 1.b), a character that is unknown in M. rapheidolabis. Macropetalichthys pelmensis Hennig, 1907 [23] is based on a fragmentary, medium-size cranial roof. It shows small sensory canals arranged in double rows. Based on what is known of the species, it differs from M. rapheidolabis in having smaller sensory canals.

Denison [21] stated that plates representing the trunk shield, including spinals, referred to Acanthaspis armata Newberry, 1875 [80], probably belong to this species. At present, there are no known remains referred to A. armata in direct association with remains referred to M. rapheidolabis, so this is not a certainty.

5. Conclusions

Macropetalichthys occupies an important place in our base of knowledge about early gnathostome evolution and paleoecology. Even as new discoveries expand our information about the timing of the jawed condition in vertebrates [2,11,77,81,82,83,84,85], add character states that inform phylogenetic analyses [2,12,21,34,35,36,37,81,82,83], and add details about habitat and life habits [2,9,81], many studies reference Macropetalichthys, one of the earliest described armored fishes [1,24,25,26]. In particular, this genus is among those central to the longstanding discussions of the monophyly or polyphyly of placoderms [2,81,82,83].

A variety of species have been referred to Macropetalichthys [19,20,21,22,23,33] but there has been a lack of clarity about the systematics and stratigraphic occurrence of some of them, partly because of the destruction of the holotype of the type species, M. rapheidolabis, in the 19th century, and partly because of the presumed loss of type specimens of other species. Designation of a neotype for M. rapheidolabis from the Delaware Limestone (Devonian, Eifelian) of Columbus, Ohio, helps resolve key nomenclatural and stratigraphic issues. The species, as recognized at present, occurs in marine carbonate and mixed carbonate–fine siliciclastic lithofacies, suggesting that it preferred relatively shallow, marine shelf habitats.

Rediscovery of the lectotype of Agassichthys sullivanti and designation of a lectotype for A. manni from the syntypic suite help stabilize the nomenclature of these two species. Both A. sullivanti and A. manni are treated as junior subjective synonyms of M. rapheidolabis. One other available species-group name, Pterichthys norwoodensis, is a junior objective synonym of M. rapheidolabis.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Battelle Engineering, Technology and Human Affairs (BETHA) Endowment, GF600375.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not available.

Informed Consent Statement

Not available.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to J.B. Krygier for his extraordinary efforts to provide for the long-term preservation of Devonian fishes in the OWU collection. I thank L.J. Anderson, W.I. Ausich, C.E. Brett, C.A. Ciampaglio, D. Dunn, D.M. Gnidovec, C. Hopps, D.M. Jones, A. Knight, J. Kube, H. Martin, H.L. McCoy, E. Mumper, J. Spina, J. Sullivan, L.M. Tabak, C.A. Ver Straeten, A.J. Wendruff, and C. Wright for assistance with some combination of locating specimens, locating reference sources, discussing stratigraphy or systematics, and arranging and moving specimens for study. In addition, I thank D.J. Jeffery and J.D. Schiffbauer for their efforts to help locate type specimens of Macropetalichthys in legacy collections Three anonymous reviewers and editors provided helpful comments leading to a substantially improved manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following institutional abbreviations, all in the USA, are used in this paper:

| MC | Marietta College, Marietta, Ohio |

| OSU | Orton Geological Museum, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio |

| OWU | Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware, Ohio |

References

- Norwood, J.G.; Owen, D.D. Description of a new fossil fish, from the Palaeozoic rocks of Indiana. Am. J. Sci. Arts 1846, 1, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Janvier, P. Early Vertebrates; Oxford Monographs on Geology and Geophysics 33; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, R.S. Features of placoderm diversification and the evolution of the arthrodire feeding mechanism. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1969, 68, 123–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.A. Arthrodire predation by Onychodus (Pisces, Crossopterygii) from the Late Devonian Gogo Formation, Western Australia. West. Austral. Mus. Rec. 1991, 15, 479–481. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.C. Phylum Chordata–vertebrate fossils. Foss. Ohio Ohio Div. Geol. Surv. Bull. 1996, 70, 288–369. [Google Scholar]

- Maisey, J.G. Discovering Fossil Fishes; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.S.L.; Westneat, M.W. Feeding mechanics and bite force modelling of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, an ancient apex predator. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.S.L.; Westneat, M.W. A biomechanical model of feeding kinematics for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi). Paleobiology 2009, 35, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, R.K. Paleoecology of Dunkleosteus terrelli. Kirtlandia 2010, 57, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.A. The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution, 2nd ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Ahlberg, P.E.; Pan, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Qiao, T.; Zhao, W.; Jia, L.; Lu, J. A Silurian maxillate placoderm illuminates jaw evolution. Science 2016, 354, 334–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, R.K. A Devonian fish tale: A new method of body length estimation suggests much smaller sizes for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira). Diversity 2023, 15, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, J.S. Chart of geological history [accompanying Report of Progress in 1869]. Geol. Surv. Ohio 1871, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. Geological structure of Ohio. In Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio Vol. 1 Geology and Paleontology. Part I. Palaeontology; Nevins & Myers: Columbus, OH, USA, 1873; pp. 140–167. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. The Paleozoic Fishes of North America; Monographs of the United States Geological Survey; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1889; Volume 16, 340p.

- Romer, A.S. Vertebrate Paleontology, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, L.E. Visualizing Earth History; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prothero, D.R.; Dott, R.H., Jr. Evolution of the Earth, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, C.R. Devonic fishes of the New York formations. In Memoirs of the New York State Museum; New York State Education Department: Albany, NY, USA, 1907; Volume 10, p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, B.G. Catalogue of Canadian fossil fishes. In Royal Ontario Museum and University of Toronto Life Sciences Contributions; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1966; Volume 68, p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, R.H. Handbook of Paleoichthyology. Volume 2. Placodermi; Gustav Fischer Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Von Meyer, H. Devonische Fisch-Reste im Eifeler Kalkstein. (Mittheilungen an Professor Bronn.). Neues Jahrb. Mineral Geogn. Geol. Petrefak.-Kunde 1846, 1846, 596–599. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig, W. Macropetalichthys pelmensis, n. sp. Zbl. Miner. Geol. Paläont. 1907, 1907, 584–591. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. Fossil fishes of the Cliff Limestone. Ann. Sci. 1853, 1, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. Fossil fishes from the Devonian rocks of Ohio. Proc. Nat. Inst. 1857, 1, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. Notes on American fossil fishes. Am. J. Sci. Arts 1862, 34, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, J.S. Report of Progress in 1869; Ohio Geological Survey: Columbus, OH, USA, 1871; pp. 3–53.

- Newberry, J.S. Descriptions of fossil fishes. In Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio. Vol. I. Geology and Palaeontology. Part II. Palaeontology; Nevins & Myers: Columbus, OH, USA, 1873; pp. 247–355. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. Beschreibung der fossilen Fische. In Bericht über die Geologische Aufnahme von Ohio. I. Band: Geologie und Paläontologie. II. Theil: Paläontologie; Louis Heinmiller: Columbus, OH, USA, 1874; pp. 247–350. [Google Scholar]

- Orton, E. Geology of Franklin County. In Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio, Vol. III. Geology and Palaeontology. Part I. Geology; Nevins & Myers: Columbus, OH, USA, 1878; pp. 596–646. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, E.D. On the characters of some Paleozoic fishes. Proc. United States Natl. Mus. 1891, 14, 449–463. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, C.R. On the characters of Macropetalichthys. Am. Nat. 1897, 31, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.R. Devonian fishes of Iowa. Iowa Geol. Surv. 1908, 18, 29–366. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Stensiö, E.A. On the head of the macropetalichthyids. Publs. Field Mus. Nat. Hist. Geol. Ser. 1925, 4, 89–197. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Jaekel, O. Neue Forschungen über das Primordial-Cranium und Gehirn Paläozoischer Fische. Paläont. Z. 1926, 8, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørvig, T. Notes on some Palaeozoic lower vertebrates from Spitsbergen and North America. Norsk Geol. Tidsskr. 1957, 37, 285–353. [Google Scholar]

- Van Valen, L. The head shield of Macropetalichthys (Arthrodira). J. Paleontol. 1963, 37, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, L.E. Rediscovery of the type specimens of the sarcopterygian fishes Onychodus sigmoides and Onychodus hopkinsi from the Devonian of Ohio, USA. Diversity 2025, 17, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesley, J.P. A Dictionary of the Fossils of Pennsylvania and Neighboring States Named in the Reports and Catalogues of the Survey; Report of Progress (Geological Survey of Pennsylvania); Board of Commissioners for the Geological Survey: Harrisburg, PA, USA, 1889; pp. 1–438.

- Miller, S.A. North American Geology and Palaeontology for the Use of Amateurs, Students, and Scientists; Western Methodist Book Concern: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1889. [Google Scholar]

- Lesley, J.P. A Summary Description of the Geology of Pennsylvania, Vol. II. Describing Upper Silurian and Devonian Formations; Geological Survey of Pennsylvania: New Cumberland, PA, USA, 1892; pp. 721–1628.

- Hay, O.P. Bibliography and catalogue of the fossil Vertebrata of North America. Bull. U.S. Geol. Surv. 1902, 179, 868. [Google Scholar]

- Hussakof, W. Catalogue of the type and figured specimens of fossil vertebrates in the American Museum of Natural History. Part I.–Fishes. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1908, 25, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Hussakof, W.; Bryant, W.L. Catalog of the fossil fishes in the Museum of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences. Bull. Buffalo Soc. Nat Sci. 1918, 12, 346. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, O.P. Second Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrates of North America; Carnegie Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1929; Volume 1, No. 390; 916p. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, L.E.; Kelley, D.F.; Krygier, J.B.; Ausich, W.I.; Dyer, D.L.; Gnidovec, D.M.; Grunow, A.M.; Jones, D.M.; Maletic, E.; Querin, C.; et al. Collections for the public good: A case study from Ohio. Diversity 2025, 17, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, E.H. Evolution of the Vertebrates; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, R.L. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlum, N.B. The Head Shield of Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis and the Shoulder Girdle of an Unknown Euarthrodire. Master’s Thesis, Miami University, Oxford, OH, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, 4th ed.; Ride, W.D.L., Cogger, H.G., Dupuis, C., Kraus, O., Minelli, A., Thompson, F.C., Tubbs, P.K., Eds.; International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature: London, UK, 2000; Available online: https://www.iczn.org/the-code/the-international-code-of-zoological-nomenclature/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Babcock, L.E. Some vertebrate types (Chondrichthys, Actinopterygii, Sarcopterygii, and Tetrapoda) from two Paleozoic Lagerstätten of Ohio, U.S.A. J. Vert. Paleont. 2024, 44, e2308621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowl, G.H. History of the Geology and Geography Department, Ohio Wesleyan University. Ohio J. Sci. 1979, 79, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, G. Middle Devonian Stratigraphy of Indiana. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1942, 52, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M.E. Building stones of the Ohio capitols. Ohio Div. Geol. Surv. Educ. Leafl. 2011, 19, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.C.; Collins, H.R. A brief history of the Ohio Geological Survey. Ohio J. Sci. 1979, 79, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lapworth, C. On the tripartite classification of the Lower Paleozoic rocks. Geol. Mag. 1879, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradstein, F.M.; Ogg, J.G.; Schmitz, M.D.; Ogg, G.M. Geologic Time Scale 2020; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, G.A. Age relations of the Middle Devonian limestones in Ohio. Ohio J. Sci. 1955, 55, 147–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.W. Middle Devonian bone beds of Ohio. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1944, 55, 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.W. Fish remains from the Middle Devonian bone beds of the Cincinnati Arch region. Palaeontogr. Am. 1944, 3, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, C.S. The Delaware Limestone. J. Geol. 1905, 13, 413–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.W. Provisional paleoecological analysis of the of the Devonian rocks of the Columbus region. Ohio J. Sci. 1947, 47, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, C.R. The Middle Devonian of Ohio; Geological Survey of Ohio: Fourth Series, Bulletin; Geological Survey of Ohio: Columbus, OH, USA, 1909; Volume 10, p. 204.

- Stauffer, C.R.; Hubbard, G.D.; Bownocker, J.A. Geology of the Columbus Quadrangle; Geological Survey of Ohio: Fourth Series, Bulletin; Geological Survey of Ohio: Columbus, OH, USA, 1911; Volume 14, p. 133.

- Westgate, L.G. Geology of Delaware County; Geological Survey of Ohio: Fourth Series, Bulletin; Geological Survey of Ohio: Columbus, OH, USA, 1926; Volume 30, p. 147.

- Ver Straeten, C.A. Basinwide stratigraphic synthesis and sequence stratigraphy, upper Pragian, Emsian and Eifelian stages (Lower to Middle Devonian), Appalachian Basin. In Devonian Events and Correlations; Becker, R.T., Kirchgasser, W.T., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Special Publications: London, UK, 2007; Volume 278, pp. 39–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kiaer, J. Upper Devonian fish remains from Ellesmere Land, with remarks on Drepanaspis. Norsk Vidensk. Akad. 2nd Norw. Art. Exp. Fram Rept. 1915, 33, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ørvig, T. Histologic studies of placoderms and fossil elasmobranchs. 1. The endoskeleton, with remarks on the hard tissues of lower vertebrates in general. Ark. Zool. 1951, 2, 321–454. [Google Scholar]

- Seilacher, A.; Reif, W.-E.; Westphal, F. Sedimentological, ecological and temporal patterns of fossil Lagerstätten. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1985, 311, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, L.E. Marine arthropod Fossil-Lagerstätten. J. Paleo. 2025, 99, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausich, W.I. Phylum Echinodermata. Ohio Div. Geol. Surv. Bull. 1996, 70, 242–261. [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis, M.K.; Brett, C.E.; Ver Straeten, C.A. Persistent depositional sequences and bioevents in the Eifelian (early Middle Devonian) of eastern Laurentia: North American evidence of the Kačák events? In Devonian Events and Correlations; Becker, R.T., Kirchgasser, W.T., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Special Publications: London, UK, 2007; Volume 278, pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- M’Coy, F. On some new fossil fish of the Carboniferous Period. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1848, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaekel, O. Die Wirbelttiere; Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, C.R. Dentition of Devonian Ptychodontidae. Am. Nat. 1898, 32, 473–488, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensiö, E. Elasmobranchiomorphi Placodermata Arthrodires. In Traité de Paléontologie; Piveteau, J., Ed.; Masson: Paris, France, 1969; pp. 71–692. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, L. A new petalichthyid placoderm from the Early Devonian of Yunnan, China. Compt. Rond. Paleovol. 2015, 14, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.S. Catalogue of the Fossil Fishes in the British Museum (Natural History, Cromwell Road., N.W.), Part II; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- von Meyer, H. Placothorax agassizi und Typodus glaber, zwei Fische im Uebergangskalke der Eifel. In Palaeontographica. Beiträge zur Naturgeschicte der Vorwelt. Erster Band; Dunker, W., von Meyer, H., Eds.; Theodor Fischer: Cassel, Germany, 1847; pp. 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. Descriptions of fossil fishes. In Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio. Volume II. Geology and Palaeontology. Part II. Palaeontology; Nevins & Myers: Columbus, OH, USA, 1875; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Young, G.C. Placoderms (armored fish): Dominant vertebrates of the Devonian Period. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2010, 38, 523–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazeau, M.; Friedman, M. The characters of Palaeozoic jawed vertebrates. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2014, 170, 779–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazeau, M.D.; Friedman, M. The origin and early phylogenetic history of jawed vertebrates. Nature 2015, 520, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupret, V.; Sanchez, S.; Goujet, D.; Tafforeau, P.; Ahlberg, P.E. A primitive placoderm sheds light on the origin of the jawed vertebrate face. Nature 2014, 507, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Q.; Lu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Gai, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wei, G.; Yu, Y.; Ahlberg, P.E.; et al. The oldest complete jawed vertebrates from the early Silurian of China. Nature 2022, 609, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).