Richness and Distribution of Mexican Pacific Cephalopods (Mollusca, Cephalopoda)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

Systematic Section

- 1 Remarks. The position of this clade is uncertain. According to [1], it is part of the Oegopsida. Based on molecular analysis, Lindgren et al. [27] and Allcock et al. [28] mention that there is enough evidence supporting the classification scheme of Young et al. [29], which we have followed herein.

- 3 Remarks. This material represents the first record for the species in the Pacific Ocean.

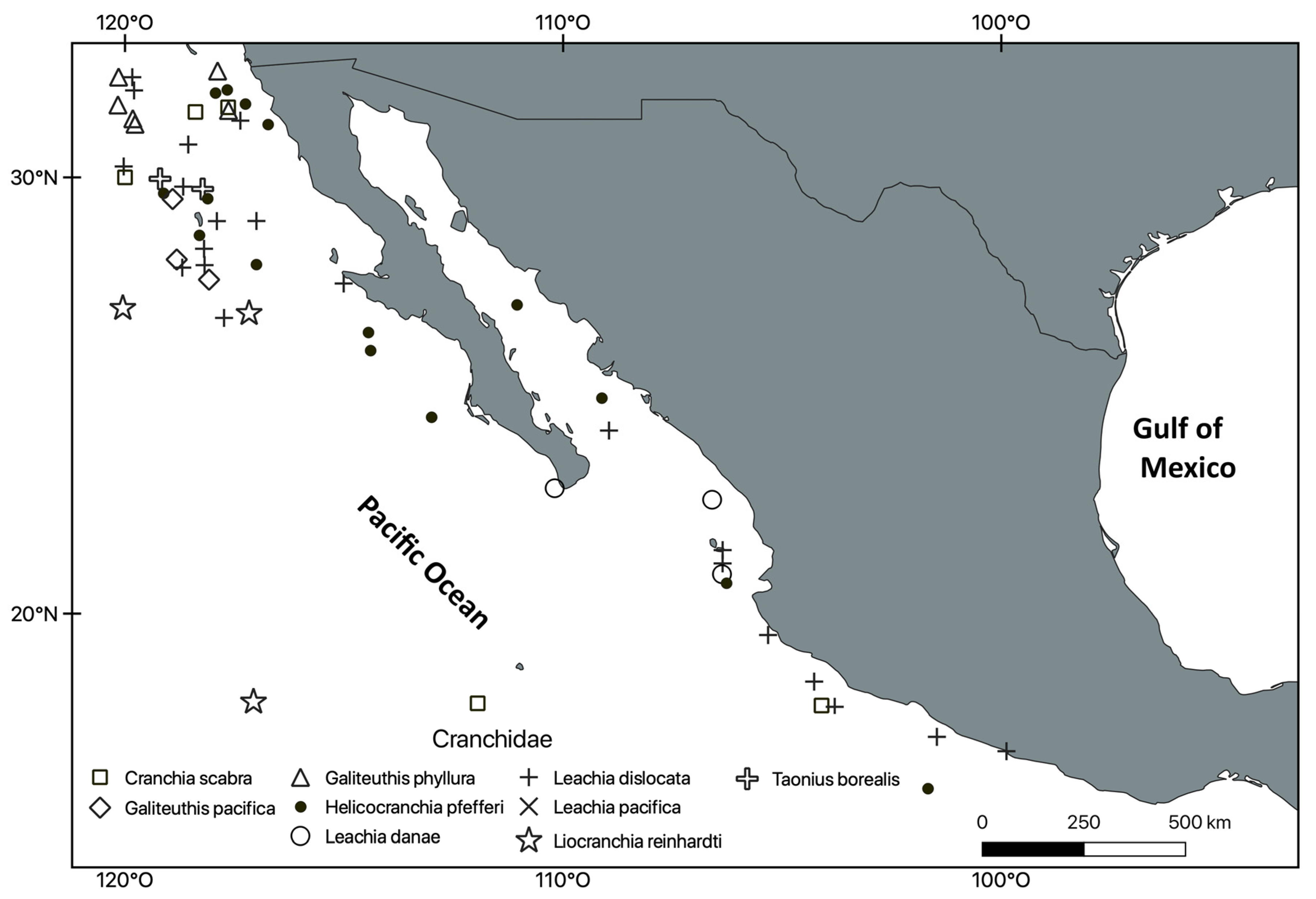

- 4 Remarks. Two specimens of T. borealis from Pacific Mexico were found in the SBNHM (9899-64 and 10842-65), both collected in the sixties. It would be useful, however, to more closely examine this material, particularly considering that Jorgensen [33] reported a third species, T. pavo (Lesueur, 1821), for the northern Pacific but its southernmost distribution limit is undefined.

- 5 Remarks. These taxa have been reviewed a couple of times since the eighties. Subgenera were not considered by Jereb et al. [6], while WoRMS, It is, and Tree of Life Web Project include the subgenera in an inconsistent way.

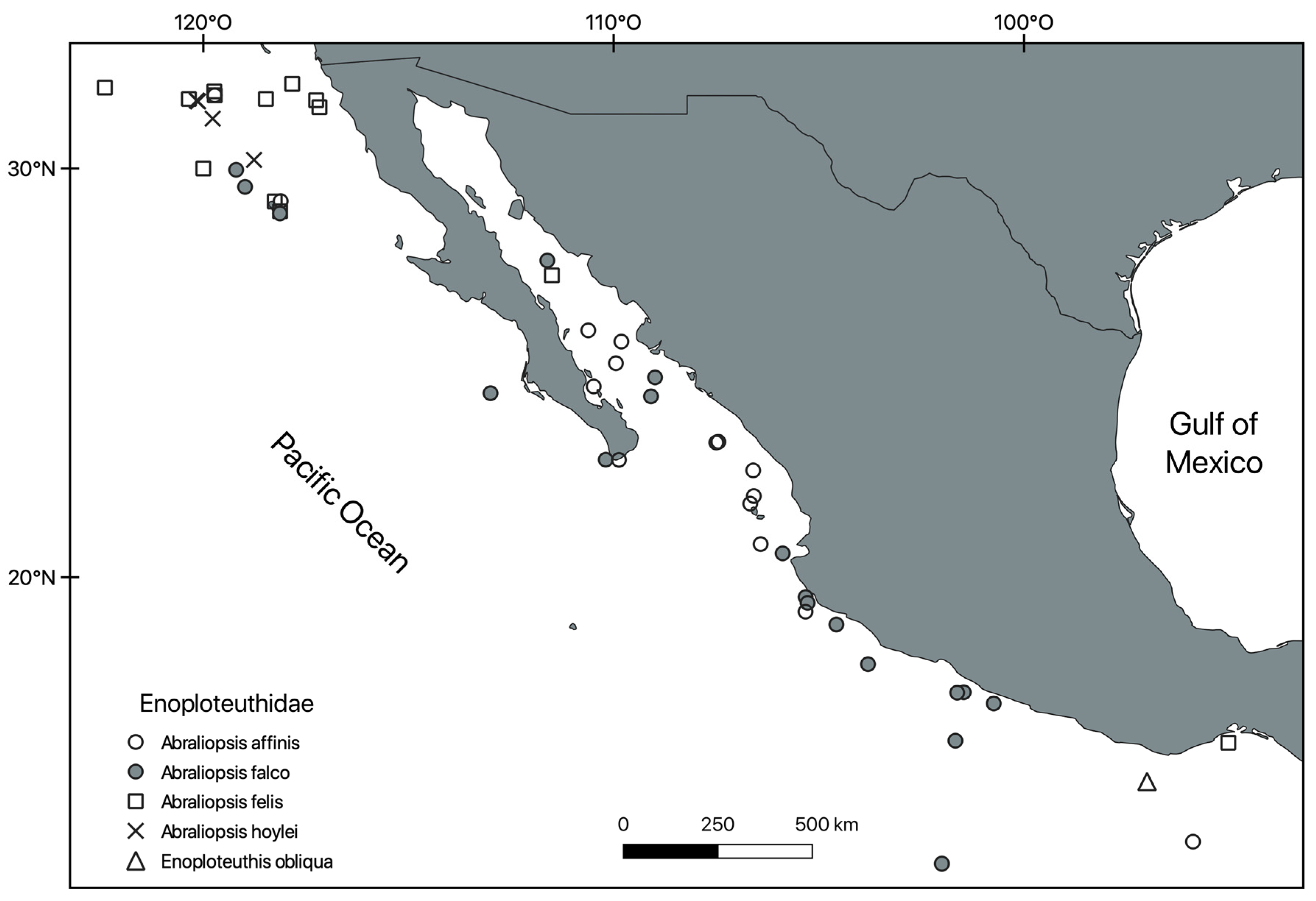

- 6 Remarks. Only one record of E. obliqua was located in the NMNH collection catalogue (Id. L.A. Burgess) and was apparently never published. This represents the first record for the Mexican Pacific.

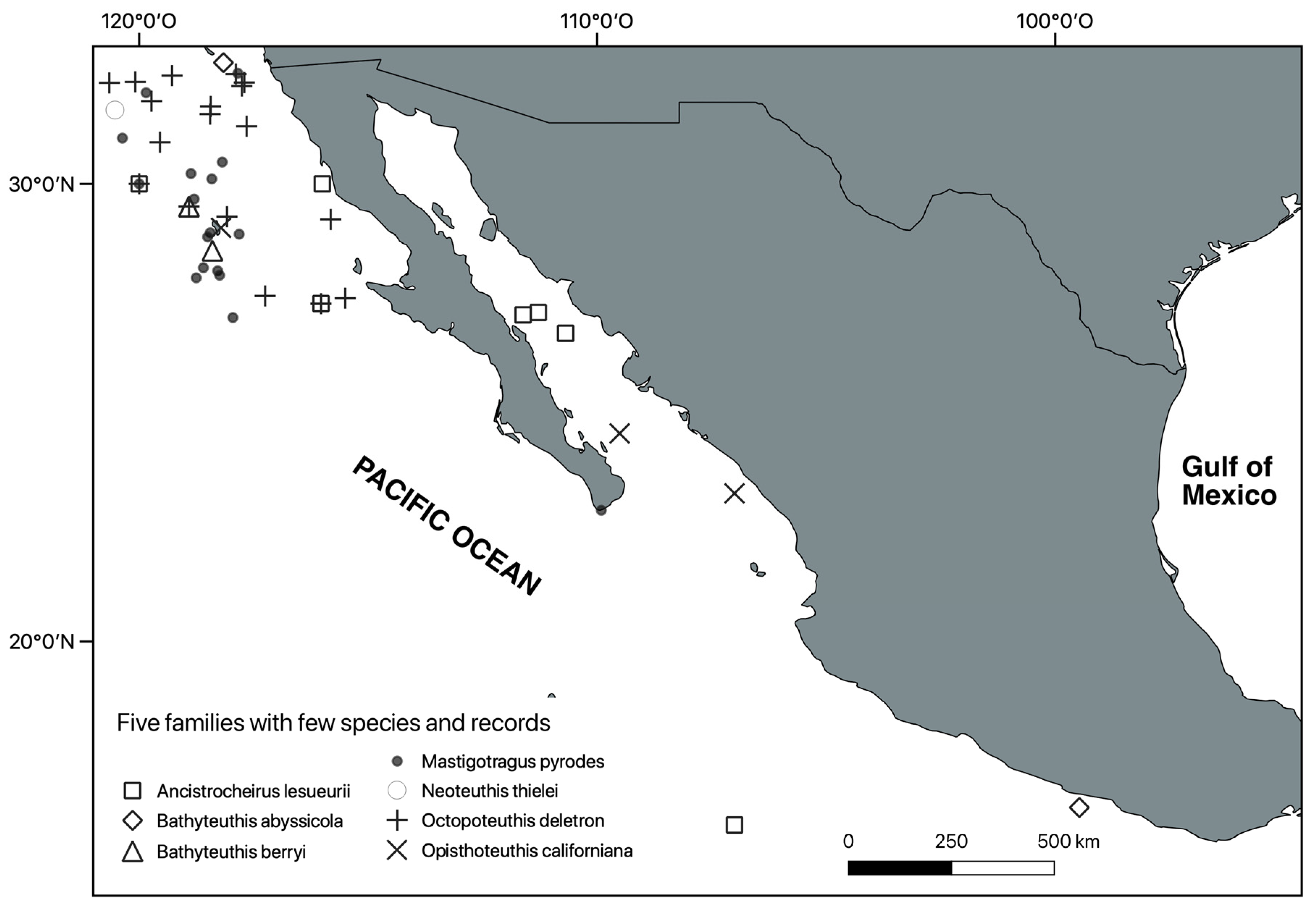

- 9 Remarks. Magnapinna pacifica is an uncommon species. In a general distribution map of a FAO document, Jereb and Roper [1] included it in the west coast of Mexico. We were not able to locate any precise records of this species for Mexico in the literature or in any collection. Young et al. [29] consider only three localities in the eastern Pacific, one just on the border between the USA and Mexico.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jereb, P.; Roper, C.F.E. Cephalopods of the World. An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Cephalopod Species Known to Date. Volume 3. Octopods and Vampire Squids; Jereb, P., Roper, C.F., Eds.; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, F.E. Cephalopoda. The Molluscan Literature: Geographic and Taxonomic Works. In The Mollusks: A Guide to their Study, Collection and Preservation; Sturm, C.F., Pearce, T.A., Valdés, Á., Eds.; Universal Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, G.L. Cephalopod Resources of the World. FAO Fish. Circ. 1973, 149, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, C.F.E.; Sweeney, M.J.; Nauen, C.E. FAO Species Catalogue. Cephalopods of the World. An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Species of Interest to Fisheries; FAO: Roma, Italy, 1984; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Jereb, P.; Roper, C.F.E. An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Cephalopods; Jereb, P., Roper, C.F.E., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jereb, P.; Roper, C.F.E.; Norman, M.D.; Finn, J. Cephalopods of the World. An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Cephalopod Species Known to Date. Volume 3. Octopods and Vampire Squids; Jereb, P., Roper, C.F.E., Norman, M.D., Finn, J., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arkhipkin, A.I.; Rodhouse, P.G.K.; Pierce, G.J.; Sauer, W.; Sakai, M.; Allcock, L.; Arguelles, J.; Bower, J.R.; Castillo, G.; Ceriola, L.; et al. World Squid Fisheries. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2015, 23, 92–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P. Cephalopods from off the Pacific Coast of Mexico: Biological Aspects of the Most Abundant Species. Sci. Mar. 2003, 67, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilly, W.F.; Zeidberg, L.D.; Booth, J.A.T.; Stewart, J.S.; Marshall, G.; Abernathy, K.; Bell, L.E. Locomotion and Behavior of Humboldt Squid, Dosidicus gigas, in Relation to Natural Hypoxia in the Gulf of California, Mexico. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 3175–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R.; Yamashiro, C.; Markaida, U.; Rodhouse, P.G.K.; Waluda, C.M.; Salinas-Zavala, C.A.; Keyl, F.; O’Dor, R.; Stewart, J.S.; Gilly, W.F. Dosidicus gigas, Humboldt Squid. In Advances in Squid Biology, Ecology and Fisheries. Part II—Oegopsid Squids; Rosa, R., Pierce, G.J., O’Dor, R.K., Eds.; Nova Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 169–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo-Plata, M.C.; Herrera-Alejo, S. First Description of Eggs and Paralarvae of Green Cctopus Octopus hubbsorum (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae) under Laboratory Conditions. Am. Malacol. Bull. 2014, 32, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliego-Cárdenas, R.; Hochberg, F.G.; De León, F.J.G.; Barriga-Sosa, I.D.L.A. Close Genetic Relationships between Two American Octopuses: Octopus hubbsorum Berry, 1953, and Octopus mimus Gould, 1852. J. Shellfish Res. 2014, 33, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva-Dávila, R.; Hochberg, F.G.; Lindgren, A.R.; del C. Franco-Gordo, M. Paralarval Development, Abundance, and Distribution of Pterygioteuthis hoylei (Cephalopoda: Oegopsida: Pyroteuthidae) in the Gulf of California, México. Molluscan Res. 2013, 33, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

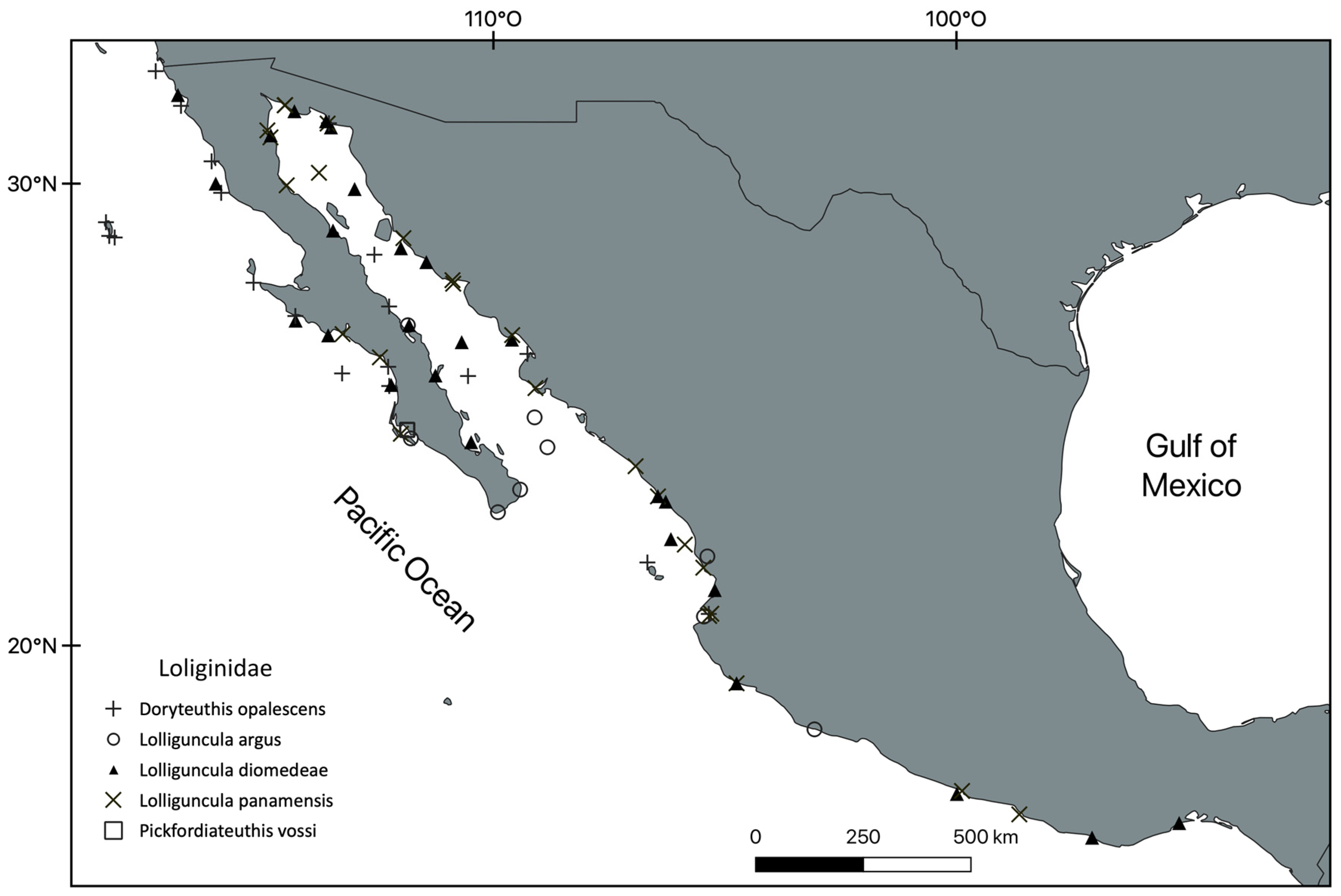

- Granados-Amores, J.; García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Hochberg, F.G.; Salinas-Zavala, C.A. The Taxonomy and Morphometry of Squids in the Family Loliginidae (Cephalopoda: Myopsida) from the Pacific Coast of Mexico. Am. Malacol. Bull. 2014, 32, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario Oficial de La Federación. Acuerdo por el Que Se da a Conocer la Actualización de la Carta Nacional Pesquera; Secretaria De Agricultura, Ganaderia, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación: Anáhuac, México, 2012; pp. 21–128. [Google Scholar]

- López-Uriarte, E.; Ríos-Jara, E. Reproductive Biology of Octopus hubbsorum (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) along the Central Mexican Pacific Coast. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2009, 84, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- López-Uriarte, E.; Ríos-Jara, E.; Pérez-Peña, M. Range Extension for Octopus hubbsorum (Mollusca: Octopodidae) in the Mexican Pacific. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2005, 77, 171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchione, M.; Jorgensen, E.M.; Sakurai, Y. Editorial: Recent Advances in the Knowledge of Cephalopod Biodiversity. Mar. Biodivers. 2017, 47, 619–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Young, R.E. The Systematics and Areal Distribution of Pelagic Cephalopods from the Seas off Southern California. Smithson. Contrib. Zool. 1972, 97, 1–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, C.F.E.; Sweeney, M.J.; Hochberg, F.G. Cefalopodos. In Guia FAO Para la Identificación de Especies Para los Fines de la Pesca. Pacifico Centro Oriental; Fischer, W., Kreep, F., Schneider, W., Sommer, C., Caspenter, K., Niem, V., Eds.; FAO: Roma, Italy, 1995; Volume I, pp. 306–353. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, M.D.; Lu, C.C. Preliminary Checklist of the Cephalopds of the South China Sea. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2000, 8, 539–567. [Google Scholar]

- Nateewathana, A.; Siriraksophon, S.; Munprasit, A. The Systematics and Distribution of Oceanic Cephalopods in the South China Sea, Area IV: Vietnamese Waters. In Proceedings of the SEAFDEC Seminar on Fisheries Resources in the South, Bangkok, Thailand, 18–20 September 2001; Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center: Bangkok, Thailand, 2001; pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Amor, M.D.; Norman, M.D.; Cameron, H.E.; Strugnell, J.M. Allopatric Speciation within a Cryptic Species Complex of Australasian Octopuses. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, G.C.B.; Avery, L.; Magda, B.; Browne, J.; Staples, D.; Syme, A.; Taylor, J.; Walker-smith, G.; Warne, M. Invertebrate Diversity of the Unexplored Marine Western Margin of Australia: Taxonomy and Implications for Global Biodiversity. Mar. Biodivers. 2014, 45, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, M.; Roper, C.F.E.; Sweeney, M.J. Marine Flora and Fauna of the Eastern United States Mollusca: Cephalopoda; NOAA Technical Report 73; National Marine Fisheries Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1989; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ponder, W.F.; Lindberg, D.R. The Cephalopoda. In Biology and Evolution of the Mollusca; Ponder, W.F., Lindberg, D.R., Ponder, J.M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; p. 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, A.R.; Pankey, M.S.; Hochberg, F.G.; Oakley, T.H. A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Cephalopoda Supports Convergent Morphological Evolution in Association with Multiple Habitat Shifts in the Marine Environment. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, A.L.; Lindgren, A.; Strugnell, J.M. The Contribution of Molecular Data to Our Understanding of Cephalopod Evolution and Systematics: A Review. J. Nat. Hist. 2015, 49, 1373–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.E. Cephalopoda Cuvier. 1797. Available online: http://tolweb.org/Cephalopoda/19386/2016.02.27 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Young, R.E.; Roper, C.F.E. A Monograph of the Cephalopoda of the North Atlantic: The Family Cycloteuthidae. Smithson. Contrib. Zool. 1969, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, Y.; Nishihara, H.; Akasaki, T.; Nikaido, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Segawa, S.; Okada, N. The Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Deep-Sea Squid (Bathyteuthis abyssicola), Bob-Tail Squid (Semirossia patagonica) and Four Giant Cuttlefish (Sepia apama, S. latimanus, S. lycidas and S. pharaonis), and Their Application To. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2013, 69, 980–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strugnell, J.; Nishiguchi, M.K. Molecular Phylogeny of Coleoid Cephalopods (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) Inferred from Three Mitochondrial and Six Nuclear Loci: A Comparison of Alignment, Implied Alignment and Analysis Methods. J. Molluscan Stud. 2007, 73, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, E.M. Field Guide to Squids and Octopuses of the Eastern North Pacific and Bearing Sea; NOAA-Sea Grant: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva-Dávila, R.; Franco-Gordo, C.; Hochberg, F.F.G.; Godínez-Domínguez, E.; Avendaño-Ibarra, R.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.; Robinson, C.J.; De Silva-Dávila, R.; Franco-Gordo, C.; Hochberg, F.F.G.; et al. Cephalopod Paralarval Assemblages in the Gulf of California during 2004–2007. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015, 520, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markaida, U.; Sosa-Nishizaki, O. Food and Feeding Habits of the Blue Shark Prionace Glauca Caught off Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico, with a Review on Its Feeding. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 2010, 90, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markaida, U.; Hochberg, F.G. Cephalopods in the Diet of Swordfish (Xiphias gladius) Caught off the West Coast of Baja California, Mexico. Pac. Sci. 2005, 59, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, R.L.; Walker, W.A.; Everett, W.T.; Pablo, J.; Reynoso, G. Population Status, Foods and Foraging of Laysan Albatrosses Phoebastria Immutabilis Nesting on Guadalupe Island, Mexico. Mar. Ornithol. 2004, 32, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J.; Bouchet, P. Histioteuthidae Verril, 1881. World Register of Marine Species. 2016. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=11749 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Castillo-Rodríguez, Z.G. Biodiversidad de Moluscos Marinos En México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2014, 85, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, M.D.; Hochberg, F.G. The Current State of Octopus Taxonomy. Phuket Mar. Biol. Cent. Res. Bull. 2005, 66, 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, G.A. Identification and Estimation of Size from the Beaks of 18 Species of Cephalopods from the Pacific Ocean; NOAA Technical Report 17; National Marine Fisheries Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Okutani, T.; McGowan, J.A. Systematics, Distribution, and Abundance of the Epiplanktonic Squid (Cephalopoda, Decapoda) Larvae of the California Current, April, 1954–March, 1957. Bull. Scripps Inst. Oceanogr. 1969, 14, 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hedgepeth, J.B. Annotated References to Technlques Capable of Assessing the Roles of Cephalopods in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean, with Emphasis on Pelagic Squids; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisherie: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg, F.G. Preliminary Key to the Benthic Cephalopods of the Eastern Pacific; Santa Barbara Natural History Museum: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo-Rodríguez, N.; Aurioles-Gamboa, D.; Montero-Muñoz, J.L. Niche Overlap and Habitat Use at Distinct Temporal Scales among the California Sea Lions (Zalophus Californianus) and Guadalupe Fur Seals (Arctocephalus Philippii Townsendi). Mar. Mammal Sci. 2016, 32, 466–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, M.; Young, R.E. Magnapinna pacifica Vecchione and Young, 1998. Pacific Bigfin Squid. Available online: http://tolweb.org/Magnapinna_pacifica/19449/2007.02.08 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Soberón, J.; Peterson, T. Biodiversity Informatics: Managing and Applying Primary Biodiversity Data. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.H.; Ferrier, S.; Huettman, F.; Moritz, C.; Peterson, A.T. New Developments in Museum-Based Informatics and Applications in Biodiversity Analysis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Vargas, M.A.; Jaime-Rivera, M. The Octopod Euaxoctopus panamensis (Octopodidae: Cephatopoda) in Mexican Waters. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1999, 47, 1139. [Google Scholar]

- Alejo-Plata, M.C.; Salgado-Ugarte, I.; Herrera-Galindo, J.; Meraz-Hernando, J. Cephalopod Biodiversity at Gulf of Tehuantepec, Mexico, Determinate from Direct Sampling and Diet Analysis on Large Pelagic-Fishes Predators. Hidrobiología 2014, 24, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Judkins, H.L.; Vecchione, M.; Roper, C.F.E.; Torres, J. Cephalopod Species Richness in the Wider Caribbean Region. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2010, 67, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Vargas, M.A. Checklist of the Cephalopods from the Gulf of Mexico. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1991, 49, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, G.L. The Cephalopods Collected by the R/V Atlantis during the West Indian Cruise of 1954. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1956, 8, 369–389. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, G.L. Biological Results of the University of Miami Deep-Sea Expeditions. 115. Euaxoctopus pillsburyae New Species Mollusca Cephalopoda from the Southern Caribbean and Surinam. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1975, 25, 346–352. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva-Dávila, R.; Avendaño-Ibarra, A.; Franco-Gordo, M.C. Calamares y Pulpos de La Costa Sur de Jalisco y Colima. In Inventario de Biodiversidad de la Costa sur de Jalisco y Colima. Volumen 1; Franco-Gordo, C., Ed.; Universidad de Guadalajara: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2013; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

| Institution | Collection Name (Acronym)/Curator | Action/Year | % Reviewed (Records in Database/Records Added) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instituto de Biología, UNAM | Colección Nacional de Moluscos (CNMO)/Edna Naranjo | Physical/2013 | 100 (0/38) |

| Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, UNAM | Colección Malacológica “Antonio García-Cubas” (COMA)/Martha Reguero | Physical/2013 | 100 (0/13) |

| Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Unidad Mazatlán, UNAM | Colección Regional de Invertebrados Marinos (EMU)/Michel E. Hendrickx | Physical/2012–2015 | 100 (29/108) |

| Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas | Colección “Maria Guadalupe López Magallón” (CLEMGLM) | Physical/2013 | 25 (ND/34) |

| Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias (CUCBA) | Colección de Invertebrados del CUCBA (CUCBA)/Eduardo Ríos Jara | Verbal consultation | No formal cephalopod collection |

| Universidad del Mar | Colección de Cefalópodos de la Universidad del Mar (UdM)/Carmen Alejo Plata. | Verbal consultation | Collection in process. Most specimens belong to Octopus hubbsorum |

| Natural History Museum of Los Angeles | Malacology Section (LACM)/Lyndsey T. Groves | Physical/2013 | 100 (0/112) |

| Santa Barbara Natural History Museum | Malacology Collection (SBMNH)/Richard Hochberg & Daniel Geiger | Electronic and physical/2013 | About 65 (166/2518) |

| California Academy of Sciences | Malacology Collection (CAS)/Christina Piotrowski | Physical and electronic/2013 | 100 (187/0) 12 new identifications |

| Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) | Pelagic Invertebrate Collections (SIO-PIC)/Mark D. Ohman | Physical and electronic/2013 | ND (423/333) |

| Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) | Benthonic Invertebrate Collection (SIO-BIC)/Greg Rouse | Physical and electronic/2013 | 85 (ND/193) |

| University of California, Museum of Paleontology | USGS Invertebrate Collections (USGS)/Erica Clites | Physical (most of the collection moved to CAS)/2013 | 100 (1/1) |

| Smithsonian Natural History Museum | Malacology Collection (USNM)/Michael Veccione | Electronic/2015 | 100 (354/0) |

| Chicago Field Museum | Department of Zoology, Invertebrate Collection (FMNH)/Janeen Jones | Electronic/2013 | 100 (5/0) |

| Harvard University, Museum of Comparative Zoology | Zoological Collection (MCZ)/Gonzalo Giribet | Electronic/2012 | 100 (12/0) |

| Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum | Gulf of California Invertebrate database/Richard C Brusca & Michel E Hendrickx | Electronic/2014 | 100 (20/0) |

| Species | Habitat | Geographic Distribution | Recorded by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enteroctopus dofleini (Wülker, 1910) | Neritic to oceanic | Panboreal in Pacific, from Japan to Baja California, Mexico. In Mexico only a marginal part of Baja California | Wolff [41]; Young [19] |

| Rossia pacifica pacifica S.S. Berry, 1911 | Neritic, mesopelagic to epipelagic | From Japan to Baja California, Mexico | Okutani and McGowan [42]; Young [19]; Hedgepeth [43], Hochberg [44], Pablo-Rodríguez et al. [45] |

| Taningia danae Joubin, 1931 | Epipelagic, oceanic | Circumglobal except poles | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Octopoteuthis sicula Rüppell, 1844 | Meso to bathypelagic | Circumglobal, antiboreal | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Octopoteuthis nielseni G. C. Robson, 1948 | Meso to bathypelagic | Tropical and subtropical Pacific | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Octopoteuthis megaptera (A. E. Verrill, 1885) | Meso to bathypelagic | Cosmopolitan | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Magnapinna pacifica Vecchione & R. E. Young, 1998 | Pelagic | Oregon, USA, to Guatemala and westwards to middle western Pacific | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Joubiniteuthis portieri (Joubin, 1916) | Meso to bathypelagic | Circumglobal, except boreal | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Abralia astrosticta S. S. Berry, 1909 | Mesopelagic | Central and western Pacific Ocean | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Abralia andamanica E. S. Goodrich, 1896 | Mesopelagic | Indian and western Pacific | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Sandalops melancholicus Chun, 1906 | Epi to bathypelagic | Circumglobal except poles | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Liguriella podophthalma Issel, 1908 | Epi to bathypelagic | Circumglobal, except boreal and equatorial | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Helicocranchia joubini (G. L. Voss, 1962) | Meso to bathypelagic | Tropical and subtropical Atlantic, SW Pacific | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Egea inermis Joubin, 1933 | Epi to bathypelagic | Circumglobal, except poles | Jereb and Roper [1] |

| Brachioteuthis picta Chun, 1910 | Epi to mesopelagic | Circumglobal, tropical and subtropical | Jereb and Roper [1] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urbano, B.; Arroyo-Lambaer, D. Richness and Distribution of Mexican Pacific Cephalopods (Mollusca, Cephalopoda). Fishes 2025, 10, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060281

Urbano B, Arroyo-Lambaer D. Richness and Distribution of Mexican Pacific Cephalopods (Mollusca, Cephalopoda). Fishes. 2025; 10(6):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060281

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrbano, Brian, and Denise Arroyo-Lambaer. 2025. "Richness and Distribution of Mexican Pacific Cephalopods (Mollusca, Cephalopoda)" Fishes 10, no. 6: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060281

APA StyleUrbano, B., & Arroyo-Lambaer, D. (2025). Richness and Distribution of Mexican Pacific Cephalopods (Mollusca, Cephalopoda). Fishes, 10(6), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060281