Fish Welfare in the Ornamental Trade: Stress Factors, Legislation, and Emerging Initiatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

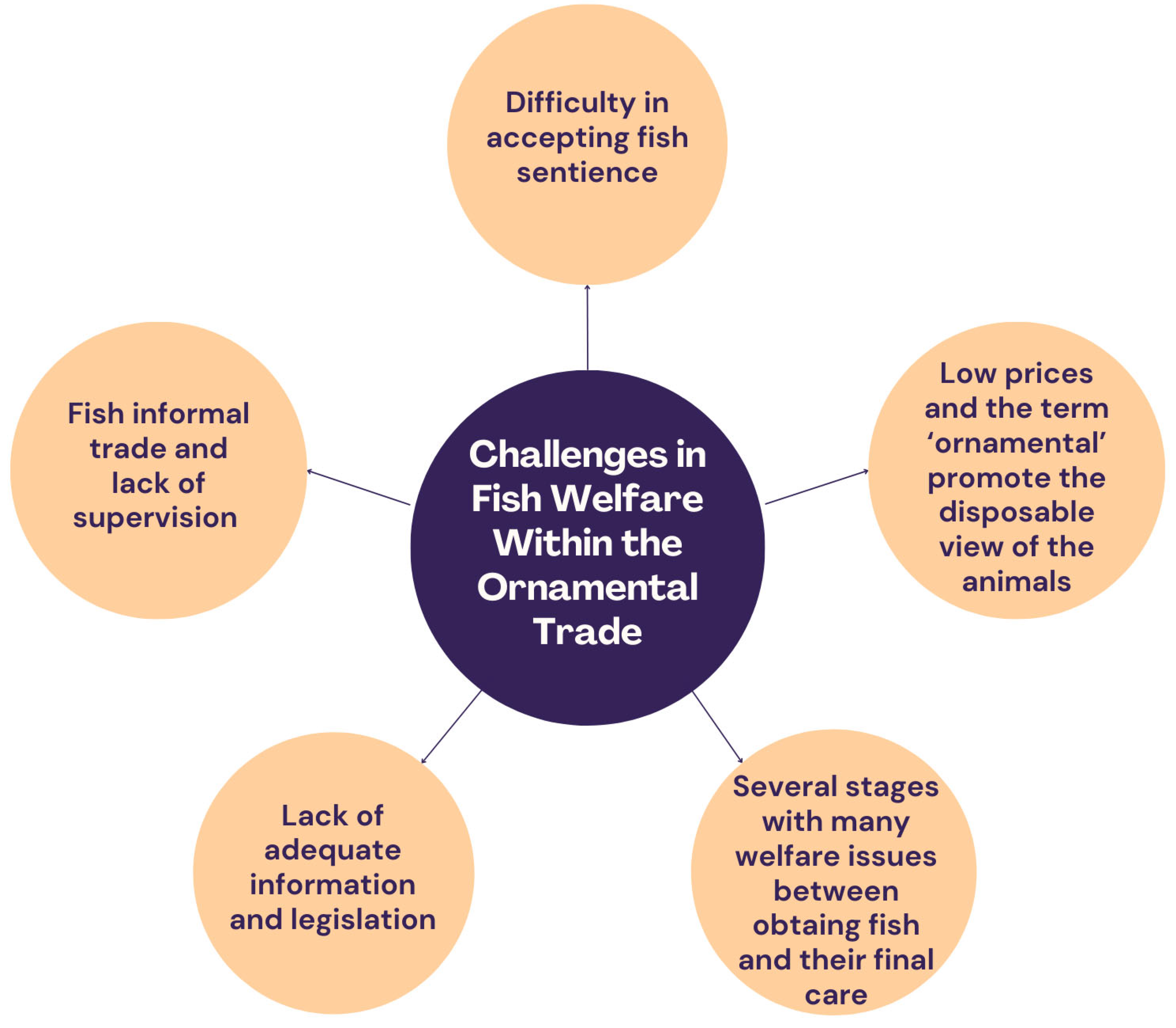

2. Fish Welfare in the Ornamental Trade

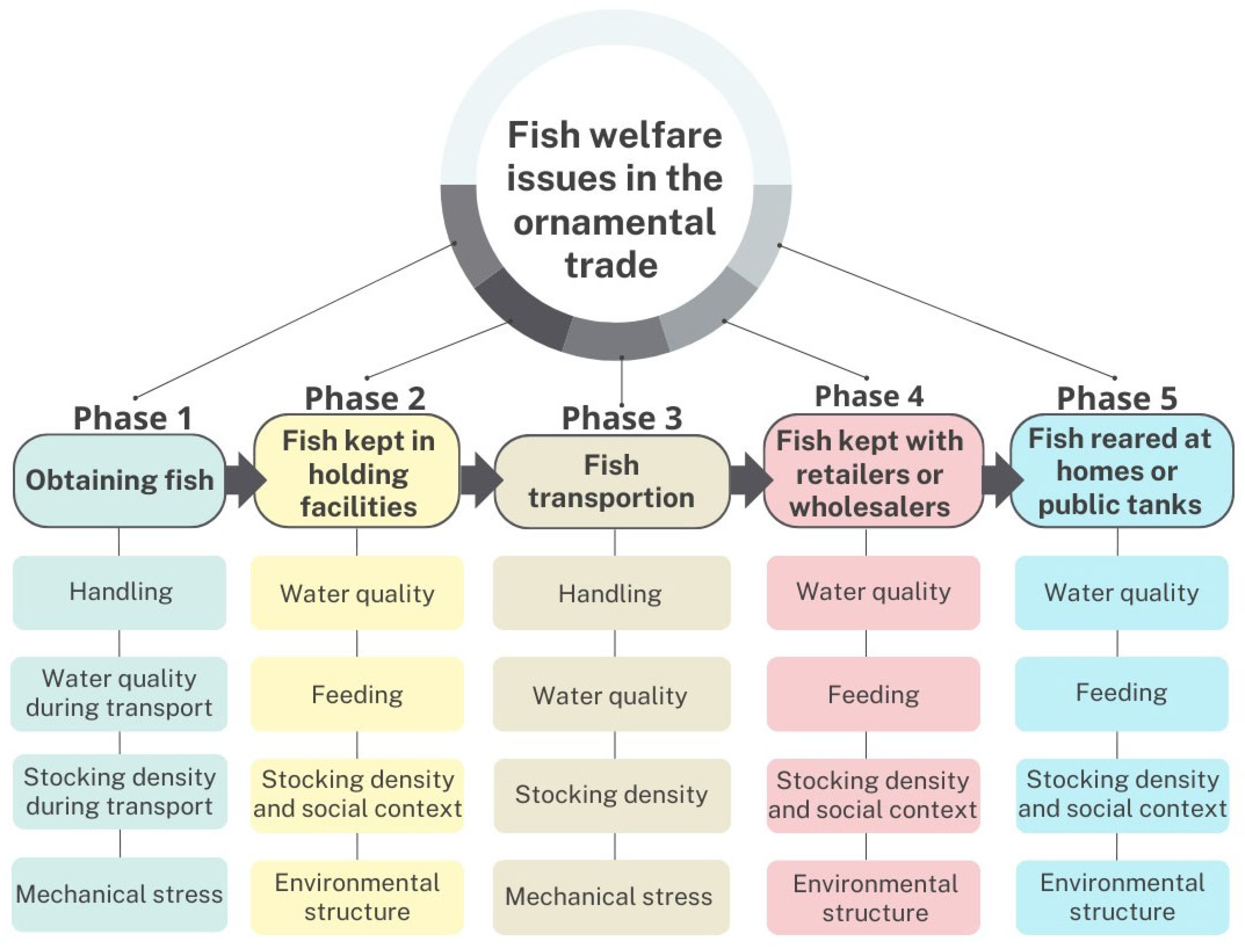

2.1. Fish Welfare Issues in the Ornamental Trade Phases

2.2. Ornamental Fish Fairs

3. Fish Welfare Indicators

4. Lack of Scientific Information

5. Lack of Legislation

6. Initiatives Promoting Fish Welfare in the Ornamental Trade

7. Rethinking Terminology: From “Ornamental” to “Pet” Fish

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saraiva, J.L.; Arechavala-Lopez, P. Welfare of fish—No longer the elephant in the room. Fishes 2019, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggles, B.K.; Arlinghaus, R.; Browman, H.I.; Cooke, S.J.; Cooper, R.L.; Cowx, I.G.; Derby, C.D.; Derbyshire, S.W.; Hart, P.J.; Jones, B.; et al. Reasons to be skeptical about sentience and pain in fishes and aquatic invertebrates. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2024, 32, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L.U.; Braithwaite, V.A.; Gentle, M.J. Do fishes have nociceptors? Evidence for the evolution of a vertebrate sensory system. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, R.; Laming, P. Mechanoreceptive and nociceptive responses in the central nervous system of goldfish (Carassius auratus) and trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Pain 2005, 6, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, V.A.; Boulcott, P. Pain perception, aversion and fear in fish. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2007, 75, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L.U. Pain in aquatic animals. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgreen, J.; Horsbergt, R.; Ranheim, B.; Chen, A.C.N. Somatosensory evoked potentials in the telencephalon of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) following galvanic stimulation of the tail. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 2007, 193, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L.U. Evolution of nociception and pain: Evidence from fish models. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20190290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L.U.; Brown, C. Mental capacities of fishes. In Neuroethics and Nonhuman Animals; Johnson, L., Fenton, A., Shriver, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon, L.U.; Braithwaite, V.A.; Gentle, M.J. Novel object test: Examining nociception and fear in the rainbow trout. J. Pain 2003, 4, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L.U. Do painful sensations and fear exist in fish? In Proceedings of the Animal Suffering: From Science to Law International Symposium, Paris, France, 18–19 October 2012; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, F.V.; Rosa, L.V.; Quadros, V.A.; de Abreu, M.S.; Santos, A.R.S.; Sneddon, L.U.; Kalueff, A.V.; Rosemberg, D.B. The use of zebrafish as a non-traditional model organism in translational pain research. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximino, C.; de Brito, T.M.; da Silva Batista, A.W.; Herculano, A.M.; Morato, S.; Gouveia, A. Measuring anxiety in zebrafish: A critical review. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 214, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozi, B.; Rodrigues, J.; Lima-Maximino, M.; de Siqueira-Silva, D.H.; Soares, M.C.; Maximino, C. Social stress increases anxiety-like behavior equally in male and female zebrafish. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 785656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.F.; McGregor, P.K.; Latruffe, C. Know thine enemy: Fighting fish gather information from observing conspecific interactions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohda, M.; Sogawa, S.; Jordan, A.L.; Kubo, N.; Awata, S.; Satoh, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Fujita, A.; Bshary, R. Further evidence for the capacity of mirror self-recognition in cleaner fish and the significance of ecologically relevant marks. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Kohda, M.; Awata, S.; Bshary, R.; Sogawa, S. Cleaner fish with mirror self-recognition capacity precisely realize their body size based on their mental image. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfman, G.; Collette, B.B.; Facey, D.E.; Bowen, B.W. The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva, J.L.; Castanheira, M.F.; Arechavala-Lopez, P.; Volstorf, J.; Studer, B.H. Domestication and welfare in farmed fish. In Animal Domestication; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, P.J. Fish welfare: Current issues in aquaculture. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 104, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntingford, F.A.; Kadri, S. Taking account of fish welfare: Lessons from aquaculture. J. Fish Biol. 2009, 75, 2862–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.H.; Croft, D.P.; Paull, G.C.; Tyler, C.R. Stress and welfare in ornamental fishes: What can be learned from aquaculture? J. Fish Biol. 2017, 91, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, H. Improving welfare assessment in aquaculture. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1060720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, C.M.; Saraiva, J.L.; Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E. Fish welfare in farms: Potential, knowledge gaps and other insights from the fair-fish database. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1450087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Morgan, T. A brief overview of the ornamental fish trade and hobby. In Fundamentals of Ornamental Fish Health; Roberts, H.E., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- King, T. Wild caught ornamental fish: A perspective from the UK ornamental aquatic industry on the sustainability of aquatic organisms and livelihoods. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 94, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novák, J.; Kalous, L.; Patoka, J. Modern ornamental aquaculture in Europe: Early history of freshwater fish imports. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2042–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares-Dias, M. Espécies de Peixes Ornamentais Capturados Pela Pesca no Estado do Amapá; Embrapa Amapá: Macapá, Brazil, 2020; Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1127796/1/CPAF-AP-2020-DOC-105-Peixes-ornamentais.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Brandão, M.L.; Dorigão-Guimarães, F.; Bolognesi, M.C.; Gauy, A.C.S.; Pereira, A.V.S.; Vian, L.; Carvalho, T.B.; Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E. Understanding behaviour to improve the welfare of ornamental fish. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 99, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Alexander, M.E.; Snellgrove, D.; Smith, P.; Bramhall, S.; Carey, P.; Henriquez, F.L.; McLellan, I.; Sloman, K.A. How should we monitor welfare in the ornamental fish trade? Rev. Aquac. 2021, 14, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Alexander, M.E.; Lightbody, S.; Snellgrove, D.; Smith, P.; Bramhall, S.; Henriquez, F.L.; McLellan, I.; Sloman, K.A. Influence of social enrichment on transport stress in fish: A behavioral approach. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 262, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Martin, K.; Christian, H.; Nathan, A.; Lauritsen, C.; Houghton, S.; Kawachi, I.; McCune, S. The pet factor—Companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouil, S.; Tlusty, M.F.; Rhyne, A.L.; Metian, M. Aquaculture of marine ornamental fish: Overview of the production trends and the role of academia in research progress. Rev. Aquac. 2019, 12, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Trade and Market News. 3rd International Ornamental Fish Trade and Technical Conference—25–26 February 2021. FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/globefish/news-events/news/news-detail/3rd-International-Ornamental-Fish-Trade-and-Technical-Conference---25-26-February-/en (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Raja, K.; Aanand, P.; Padmavathy, S.; Sampathkumar, J.S. Present and future market trends of Indian ornamental fish sector. Int. J. Fish Aquat. Stud. 2019, 7, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Maceda-Veiga, A.; Domínguez, O.; Escribano-Alacid, J.; Lyons, J. The aquarium hobby: Can sinners become saints in freshwater fish conservation? Fish Fish. 2016, 17, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metar, S.; Chogale, N.; Shinde, K.; Satam, S.; Sadawarte, V.; Sawant, A.; Nirmale, V.; Pagarkar, A.; Singh, H. Transportation of live marine ornamental fish. J. Adv. Agric. Technol. 2018, 2, 206–208. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderzwalmen, M.; Eaton, L.; Mullen, C.; Henriquez, F.; Carey, P.; Snellgrove, D.; Sloman, K.A. The use of feed and water additives for live fish transport. Rev. Aquac. 2019, 11, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderzwalmen, M.; Carey, P.; Snellgrove, D.; Sloman, K.A. Benefits of enrichment on the behaviour of ornamental fishes during commercial transport. Aquaculture 2020, 526, 735360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Aquiloni, L.; Inghilesi, A.F.; Giuliani, C.; Lazzaro, L.; Ferretti, G.; Lastrucci, L.; Foggi, B.; Tricarico, E. Aliens just a click away: The online aquarium trade in Italy. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2015, 6, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.K.M.; Oliveira, T.P.R.; Rosa, I.L.; Braga-Pereira, F.; Ramos, H.A.C.; Rocha, L.A.; Alves, R.R.N. Caught in the (inter)net: Online trade of ornamental fish in Brazil. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 263, 109344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Carvalho, F.A.C. Global invasion and biosecurity risk from the online trade in ornamental crayfish. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 38, e14359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntingford, F.A.; Adams, C.; Braithwaite, V.A.; Kadri, S.; Pottinger, T.G.; Sandøe, P.; Turnbull, J.F. Current issues in fish welfare. J. Fish Biol. 2006, 68, 332–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, J.H.; Azra, M.N. A global review of ornamental fish and shellfish research. Aquaculture 2024, 741719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portz, D.E.; Woodley, C.M.; Cech, J.J., Jr. Stress-associated impacts of short-term holding on fishes. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2006, 16, 125–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, J.L.; Rachinas-Lopes, P.; Arechavala-Lopez, P. Finding the “golden stocking density”: A balance between fish welfare and farmers’ perspectives. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 930221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J.M.; Feist, G.W.; Varga, Z.M.; Westerfield, M.; Kent, M.L.; Schreck, C.B. Whole-body cortisol is an indicator of crowding stress in adult zebrafish, Danio rerio. Aquaculture 2006, 258, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, F.D.F.; Freire, C.A. An overview of stress physiology of fish transport: Changes in water quality as a function of transport duration. Fish Fish. 2016, 17, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ye, Z.; Qi, M.; Cai, W.; Saraiva, J.L.; Wen, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, J. Water quality impact on fish behavior: A review from an aquaculture perspective. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e12985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, N.; Ellison, A.; Cable, J. A neglected fish stressor: Mechanical disturbance during transportation impacts susceptibility to disease in a globally important ornamental fish. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2019, 134, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, D.R.; Arvigo, A.L.; Giaquinto, P.C.; Delicio, H.C.; Barcellos, L.J.G.; Barreto, R.E. Effects of clove oil on behavioral reactivity and motivation in Nile tilapia. Aquaculture 2021, 532, 736045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintuprom, C.; Nuchchanart, W.; Dokkaew, S.; Aranyakanont, C.; Ploypan, R.; Shinn, A.P.; Wongwaradechkul, R.; Dinh-Hung, N.; Dong, H.T.; Chatchaiphan, S. Effects of clove oil concentrations on blood chemistry and stress-related gene expression in Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens) during transportation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1392413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, M.; Oliveira, M.; Jerez-Cepa, I.; Franco-Martínez, L.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Tort, L.; Mancera, J.M. Transport and recovery of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.) sedated with clove oil and MS222: Effects on oxidative stress status. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, V.A. Do Fish Feel Pain? Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gumilar, I.; Rizal, A.; Sriati Putra, R.S. Analysis of consumer behavior in decision making of purchasing ornamental freshwater fish (case of study at ornamental freshwater fish market at Peta Street, Bandung). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 137, p. 012081. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, C.I.M.; Galhardo, L.; Noble, C.; Damsgård, B.; Spedicato, M.T.; Zupa, W.; Beauchaud, M.; Kulczykowska, E.; Massabuau, J.C.; Carter, T.; et al. Behavioural indicators of welfare in farmed fish. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segner, H.; Sundh, H.; Buchmann, K.; Douxfils, J.; Sundell, K.S.; Mathieu, C.; Ruane, N.; Jutfelt, F.; Toften, H.; Vaughan, L. Health of farmed fish: Its relation to fish welfare and its utility as welfare indicator. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Føre, M.; Frank, K.; Norton, T. Precision fish farming: A new framework to improve production in aquaculture. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 173, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, J.L.; Arechavala-Lopez, P.; Castanheira, M.F.; Volstorf, J.; Studer, B.H. A global assessment of welfare in farmed fishes: The fishethobase. Fishes 2019, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sink, T.D.; Lochmann, R.T.; Fecteau, K.A. Validation, use, and disadvantages of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for detection of cortisol in channel catfish, largemouth bass, red pacu and golden shiners. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2007, 75, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesto, M.; Hernández, J.; López-Patiño, M.A.; Soengas, J.L.; Míguez, J.M. Is gill cortisol concentration a good acute stress indicator in fish? A study in rainbow trout and zebrafish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 188, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoul, B.; Geffroy, B. Measuring cortisol, the major stress hormone in fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 94, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, B.A.; Ribas, L.; Acerete, L.; Tort, L. Effects of chronic confinement on physiological responses of juvenile gilthead sea bream, Sparus aurata L.; to acute handling. Aquac. Res. 2005, 36, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M.O.; Rey Planellas, S.; Yang, Y.; Phillips, C.; Descovich, K. Emerging indicators of fish welfare in aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.R. Angelfish: A Complete Pet Owner’s Manual. Barron’s Educational Series, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gauy, A.C.S.; Boscolo, C.N.P.; Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E. Less water renewal reduces effects on social aggression of the cichlid Pterophyllum scalare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 198, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. All About Aquariums. 2009. Available online: https://en.aqua-fish.net/feb_ebook_full.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Larcombe, E.; Alexander, M.E.; Snellgrove, D.; Henriquez, F.L.; Sloman, K.A. Current disease treatments for the ornamental pet fish trade and their associated problems. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 17, e12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maceda-Veiga, A.; Cable, J. Efficacy of sea salt, metronidazole and formalin-malachite green baths in treating Icthyophthirius multifiliis infections of mollies (Poecilia sphenops). Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 2014, 34, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M.A.A.; Nasren, S.; Srinivasa, K.H.; Rathore, S.S.; Abhiman, P.B.; Rakesh, K. Heavy infection of Ichthyophthirius multifiliis in striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus, Sauvage 1878) and its treatment trial by different therapeutic agents in a control environment. J. Appl. Aquac. 2020, 32, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, W.V.; Ziemniczak, H.M.; Bacha, F.B.; Fernandes, R.B.S.; Fujimoto, R.Y.; Sousa, R.M.; Saturnino, K.C.; Honorato, C.A. Respiratory profile and gill histopathology of Carassius auratus exposed to different salinity concentrations. Semin. Ciências Agrárias 2021, 42, 2993–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintuprom, C.; Nuchchanart, W.; Dokkaew, S.; Aranyakanont, C.; Ploypan, R.; Shinn, A.P.; Wongwaradechkul, R.; Dinh-Hung, N.; Dong, H.T.; Chatchaiphan, S. Effects of confinement rearing and sodium chloride treatment on stress hormones and gene expression in Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens). J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2025, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galhardo, L. My Fish and I: Human-Fish Interactions in the 21st Century. J. Appl. Anim. Ethics Res. 2021, 3, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maia, C.M.; Gauy, A.C.d.S.; Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E. Fish Welfare in the Ornamental Trade: Stress Factors, Legislation, and Emerging Initiatives. Fishes 2025, 10, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10050224

Maia CM, Gauy ACdS, Gonçalves-de-Freitas E. Fish Welfare in the Ornamental Trade: Stress Factors, Legislation, and Emerging Initiatives. Fishes. 2025; 10(5):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10050224

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaia, Caroline Marques, Ana Carolina dos Santos Gauy, and Eliane Gonçalves-de-Freitas. 2025. "Fish Welfare in the Ornamental Trade: Stress Factors, Legislation, and Emerging Initiatives" Fishes 10, no. 5: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10050224

APA StyleMaia, C. M., Gauy, A. C. d. S., & Gonçalves-de-Freitas, E. (2025). Fish Welfare in the Ornamental Trade: Stress Factors, Legislation, and Emerging Initiatives. Fishes, 10(5), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10050224