Neurotransmitter and Gut–Brain Metabolic Signatures Underlying Individual Differences in Sociability in Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Social Preference Tests

2.3. Neurotransmitter-Targeted Metabolomics Analysis

2.4. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

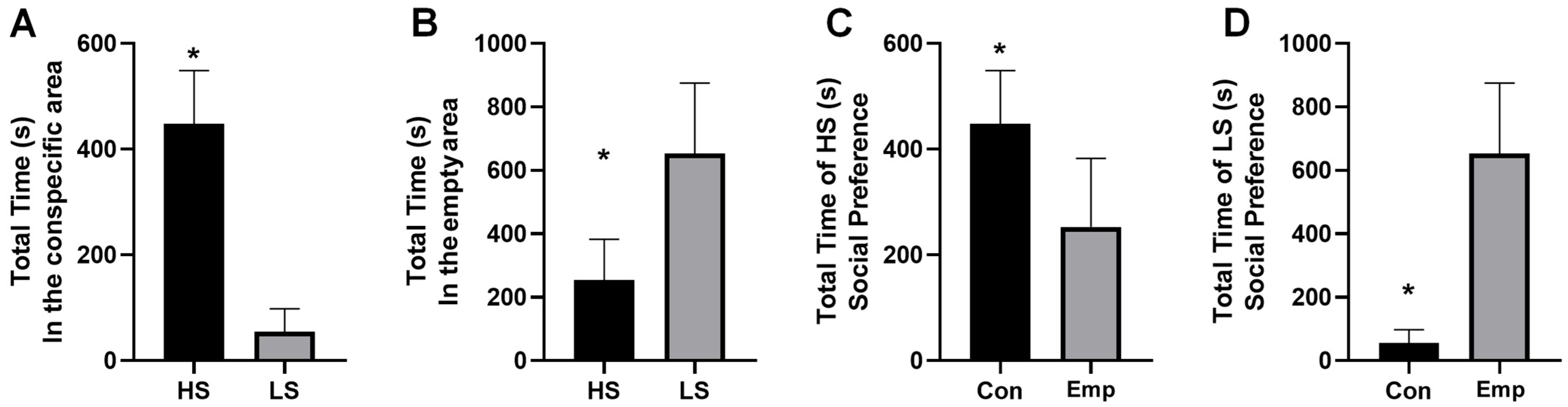

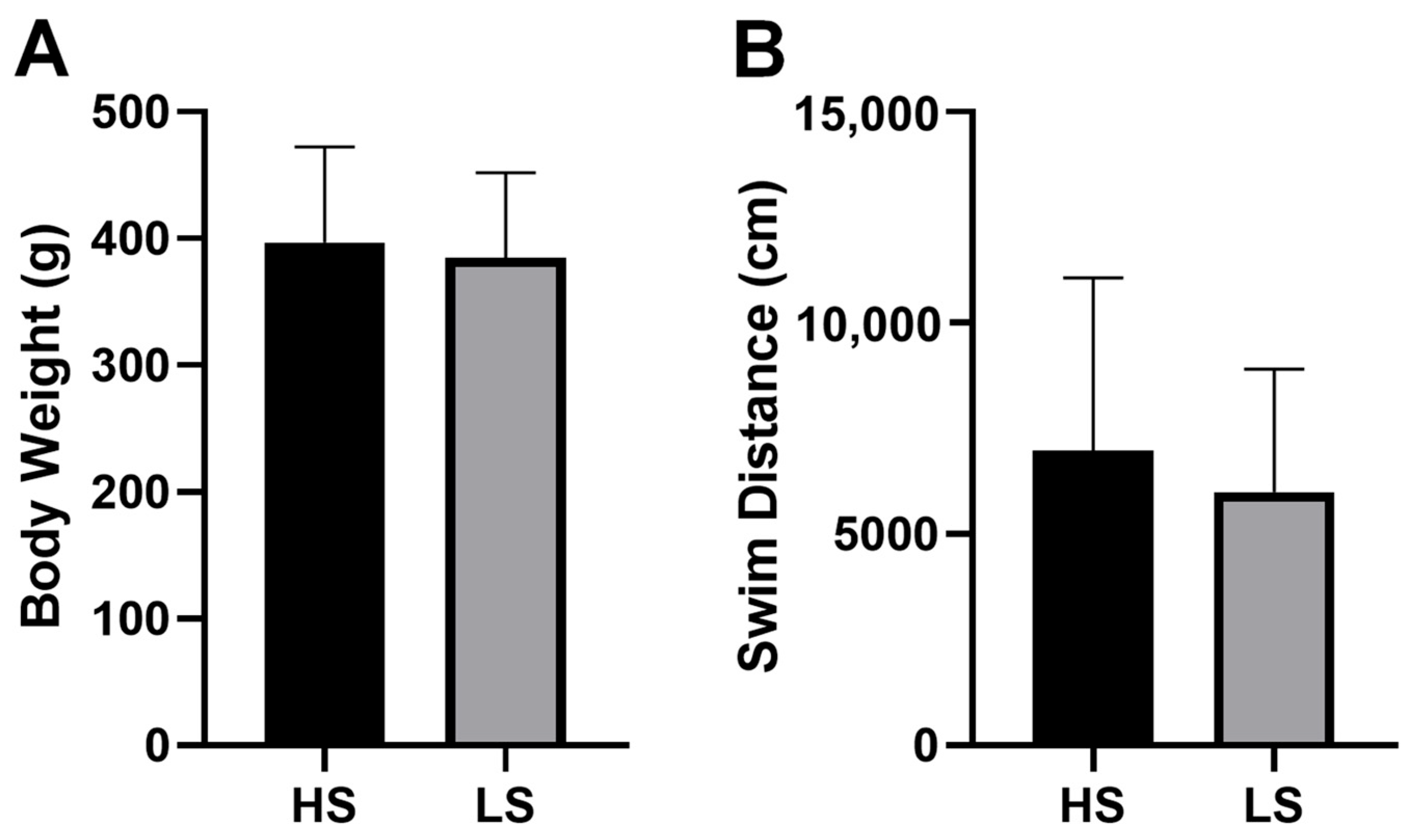

3.1. Social Preference Test

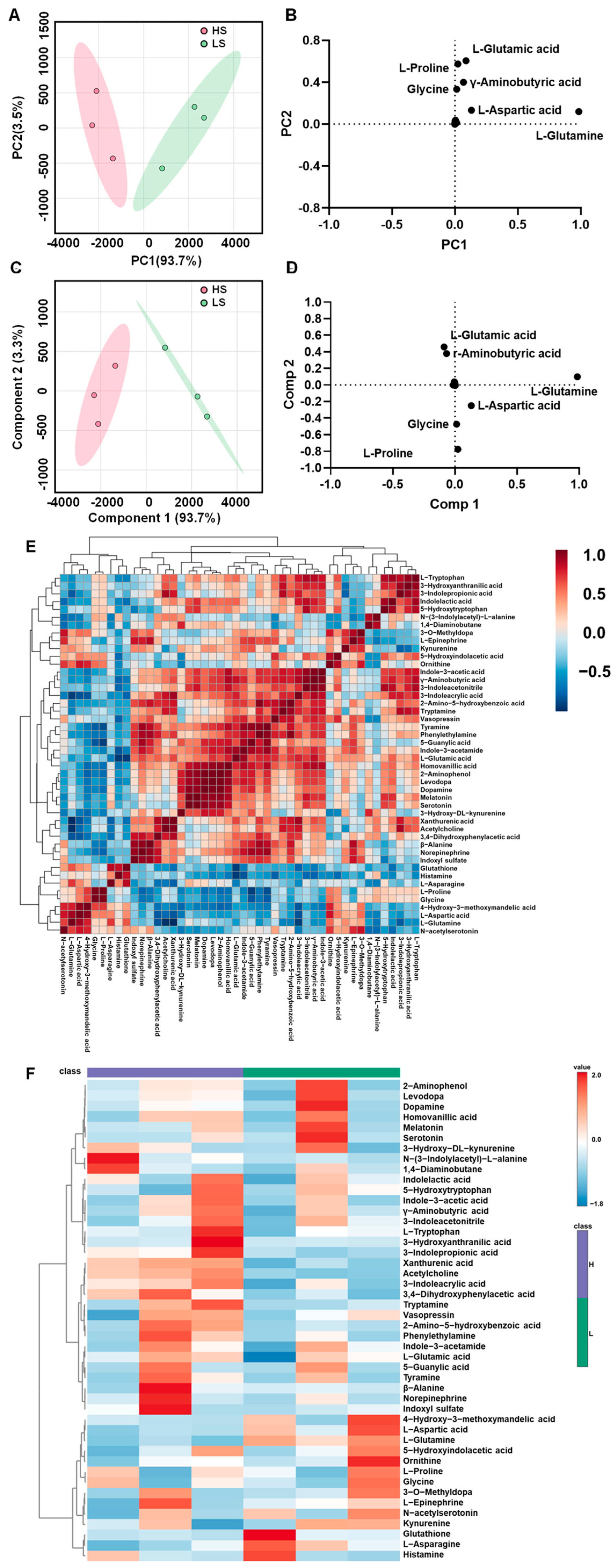

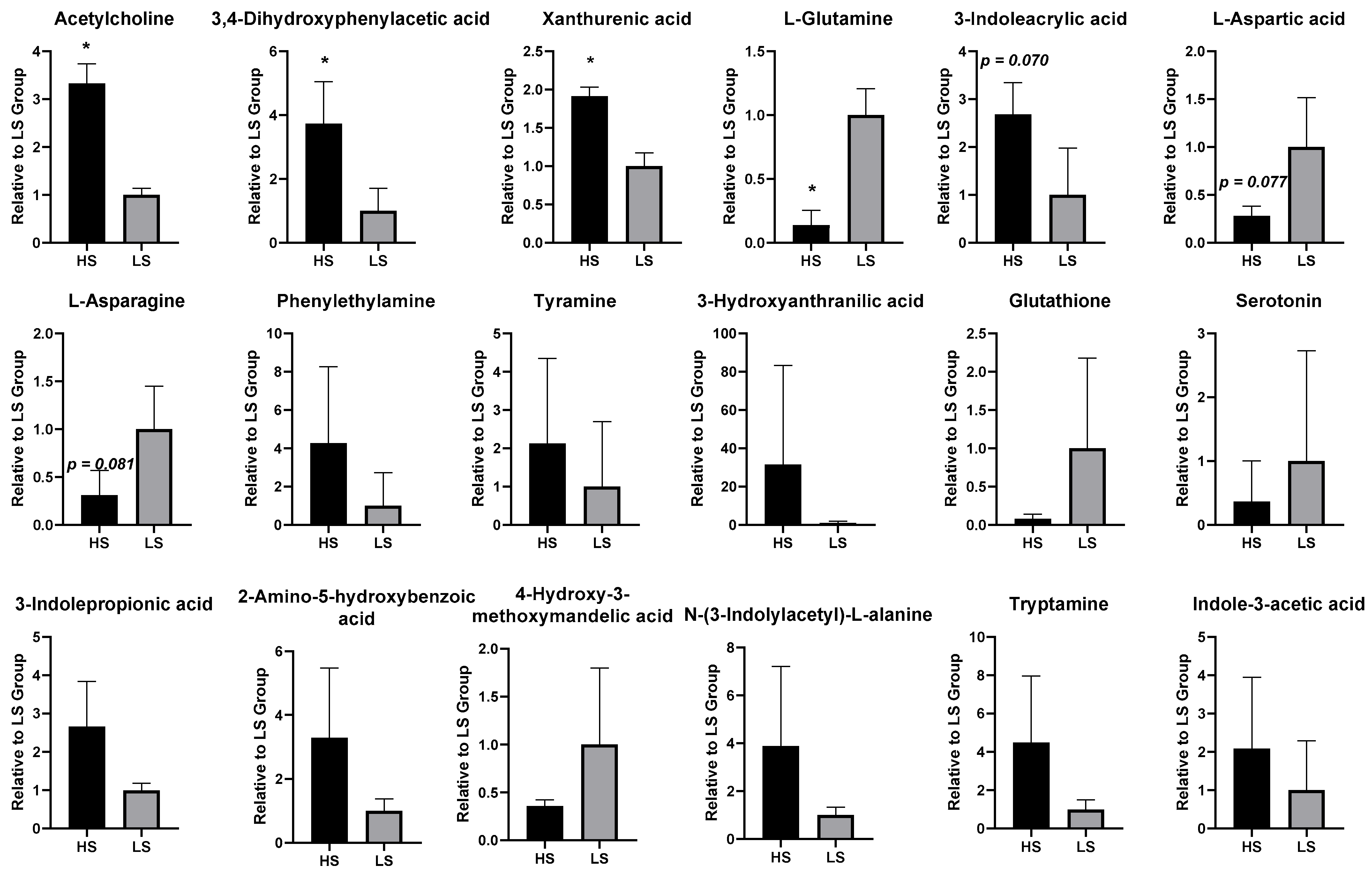

3.2. Brain Targeted Neurotransmitter Metabolomic Profiling Between the HS and LS Groups

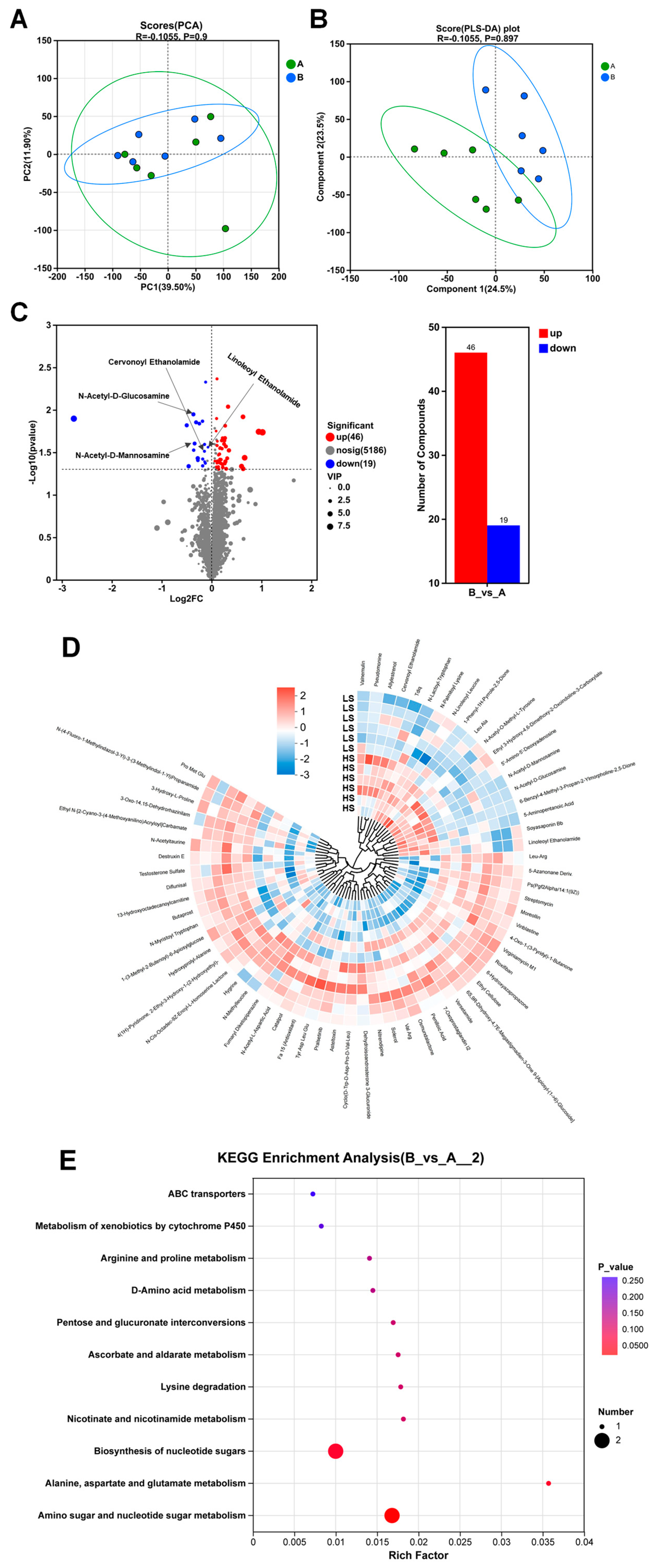

3.3. Intestine Metabolomic Profiling Between the HS and LS Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krause, J.; Ruxton, G.D. Living in Groups; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Peichel, C.L. Social behavior: How do fish find their shoal mate? Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R503–R504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdahl, A.M.; Kao, A.B.; Flack, A.; Westley, P.A.H.; Codling, E.A.; Couzin, I.D.; Dell, A.I.; Biro, D. Collective animal navigation and migratory culture: From theoretical models to empirical evidence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.W.; Volkoff, H.; Narnaware, Y.; Bernier, N.J.; Peyon, P.; Peter, R.E. Brain regulation of feeding behavior and food intake in fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A-Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2000, 126, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.W.; Horng, J.L.; Chou, M.Y. Fish Behavior as a Neural Proxy to Reveal Physiological States. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Lopez, A.; Bloch, N.I.; van der Bijl, W.; Cortazar-Chinarro, M.; Szorkovszky, A.; Kotrschal, A.; Darolti, I.; Buechel, S.D.; Romenskyy, M.; Kolm, N.; et al. Functional convergence of genomic and transcriptomic architecture underlies schooling behaviour in a live-bearing fish. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Réale, D.; Reader, S.M.; Sol, D.; McDougall, P.T.; Dingemanse, N.J. Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol. Rev. 2007, 82, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartland, L.A.; Firth, J.A.; Laskowski, K.L.; Jeanson, R.; Ioannou, C.C. Sociability as a personality trait in animals: Methods, causes and consequences. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougnon, G.; Matsui, H. Environmental context modulates sociability in ube3a zebrafish mutants via alterations in sensory pathways. Mol. Psychiatr. 2025, 31, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.Q.; Tian, Y.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Han, J.; Tai, F.D.; Jia, R. Social environment enrichment alleviates anxiety-like behavior in mice: Involvement of the dopamine system. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 456, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, D.J.T.; Szorkovszky, A.; Kotrschal, A.; Kolm, N.; Herbert-Read, J.E. Using activity and sociability to characterize collective motion. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panula, P.; Sallinen, V.; Sundvik, M.; Kolehmainen, J.; Torkko, V.; Tiittula, A.; Moshnyakov, M.; Podlasz, P. Modulatory Neurotransmitter Systems and Behavior: Towards Zebrafish Models of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Zebrafish 2006, 3, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.S.; Li, D.; Lei, H.J.; Wei, X.R.; Schlenk, D.; Mu, J.L.; Chen, H.X.; Yan, B.; Xie, L.T. Dietary Seleno-L-Methionine Causes Alterations in Neurotransmitters, Ultrastructure of the Brain, and Behaviors in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 11894–11905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, D.; Popic, J.; Enns, J.P.; Inserra, A.; Skalecka, A.; Markopoulos, A.; Posa, L.; Lopez-Canul, M.; Qianzi, H.; Lafferty, C.K.; et al. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) promotes social behavior through mTORC1 in the excitatory neurotransmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stettler, P.R.; Antunes, D.F.; Taborsky, B. The serotonin 1A receptor modulates the social behaviour within groups of a cooperatively-breeding cichlid. Horm. Behav. 2021, 129, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, L.A.D.; Pyterson, M.P.; Pimentel, A.F.N.; Araujo, F.; Souza, L.; Mendes, C.H.M.; Costa, B.P.D.; Siqueira-Silva, D.H.D.; Maximino, M.L.; Maximino, C. Roles of the 5-HT2C receptor on zebrafish sociality. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 125, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L.; Oliveira, L.N.; Costa, B.P.D.; Lima-Maximino, M.; Veloso, V.; Maximino, C. Roles of the 5-HT1A receptor in zebrafish responses to potential threat and in sociality. J. Psychopharmacol. 2025, 39, 1476–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.L.; Wang, X.F.; Feng, J.C.; Su, X.; Liang, J.P.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.X. Impact of chronic exposure to trichlorfon on intestinal barrier, oxidative stress, inflammatory response and intestinal microbiome in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Sandhu, K.; Peterson, V.; Dinan, T.G. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.Q.; Liu, S.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.X.; Gu, C.; Ren, H.Q.; Wu, B. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Size-Dependent Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics on Immune and Secretory Cell Populations from Zebrafish Intestines. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3417–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maares, M.; Haase, H. A Guide to Human Zinc Absorption: General Overview and Recent Advances of In Vitro Intestinal Models. Nutrients 2020, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallino, L.; Rincón, L.; Scaia, M.F. Social behaviors as welfare indicators in teleost fish. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; McKay, G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In Handbook of Psychology and Health, Volume IV; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, J.C.; Jing, Y. Larimichthys crocea (large yellow croaker): A bibliometric study. Heliyon 2024, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics—Yearbook 2023; FAO Yearbook of Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Cachat, J.M. Zebrafish Neurobehavioral Protocols; Allan, V., Kalueff, J.M.C., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Stewart, A.M. Zebrafish Protocols for Neurobehavioral Research; Allan, V., Kalueff, A.M.S., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Laland, K. Social enhancement and social inhibition of foraging behaviour in hatchery-reared Atlantic salmon. J. Fish Biol. 2002, 61, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Qian, M.Z.; Li, Z.; Feng, Z.H.; Luo, S.Y.; Gao, Q.F.; Hou, Z.S. Low light intensity dysregulated growth and behavior of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) via microbiota-gut-brain axis. Aquaculture 2025, 603, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, J.D.; Zhou, G.Y.; Lu, Y.; Kolic, J.; Ellis, C.; Johnson, J.D.; Macdonald, P.E.; Xia, J.G. Web-based multi-omics integration using the Analyst software suite. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.Y.; Hui, F.A.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; Macdonald, P.E.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S.Z.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W398–W406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocha, G.D.; Floden, A.M.; Miller, N.M.; Smith, A.J.; Nagamoto-Combs, K.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Combs, C.K. Temporal progression of Alzheimer’s disease in brains and intestines of transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging 2019, 81, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, L.H.; Schreiber, H.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Hou, Z.S.; Luo, H.R.; Cui, X.F.; Xiao, J.; Kim, Y.B.; Li, J.L.; Feng, W.R.; Tang, Y.K.; Li, H.X.; et al. Zinc alters behavioral phenotypes, neurotransmitter signatures, and immune homeostasis in male zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Hou, Z.-S.; Luo, H.-R.; Li, H.-X.; Cui, X.-F.; Li, J.-L.; Feng, W.-R.; Tang, Y.-K.; Su, S.-Y.; Gao, Q.-F.; et al. Neurobehavioral disorders induced by environmental zinc in female zebrafish (Danio rerio): Insights from brain and intestine transcriptional and metabolic signatures. Chemosphere 2023, 335, 138962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. The adaptive significance of schooling as an antipredator defense in fish. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 1990, 27, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz, R.; Schneidman, E. Social interactions drive efficient foraging and income equality in groups of fish. eLife 2020, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpato, G.L.; Fernandes, M.O. SOCIAL-CONTROL OF GROWTH IN FISH. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1994, 27, 797–810. [Google Scholar]

- Maruska, K.P. Social regulation of reproduction in male cichlid fishes. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2014, 207, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, A.; Inahata, M.; Shimomura, Y.; Kagawa, N. Physiological changes in response to social isolation in male medaka fish. Fish. Sci. 2020, 86, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, D.F.; Soares, M.C.; Taborsky, M. Dopamine modulates social behaviour in cooperatively breeding fish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 550, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, F.; Yin, L.F.; Shi, S.N.; Hu, B.; Qu, H.; Zheng, L. Dopamine Level Affects Social Interaction and Color Preference Possibly Through Intestinal Microbiota in Zebrafish. Zebrafish 2022, 19, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvat, G.; Kimchi, T. Acetylcholine Elevation Relieves Cognitive Rigidity and Social Deficiency in a Mouse Model of Autism. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, R.; Fung, B.; Sturm, R.; De Biasi, M. Abnormal Social Behavior in Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor β4 Subunit-Null Mice. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomini, A.; Bueno, B.W.; Marcon, L.; Scolari, N.; Genario, R.; Demin, K.A.; Kolesnikova, T.O.; Kalueff, A.; de Abreu, M.S. An acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, donepezil, increases anxiety and cortisol levels in adult zebrafish. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitre, M.; Taleb, O.; Jeltsch-David, H.; Klein, C.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G. Xanthurenic acid: A role in brain intercellular signaling. J. Neurochem. 2024, 168, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Koitabashi, T.; Koshiro, A. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of l-dopa in rats. II. effect of l-dopa on dopamine and dopamine metabolite concentration in rat striatum. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1994, 17, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megaw, P.; Morgan, I.; Boelen, M. Vitreal dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) as an index of retinal dopamine release. J. Neurochem. 2001, 76, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.J.; Yates, C.; Peterson, R.T. Social behavioral profiling by unsupervised deep learning reveals a stimulative effect of dopamine D3 agonists on zebrafish sociality. Cell Rep. Methods 2023, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, I.; Asanuma, M. Dopaminergic neuron-specific oxidative stress caused by dopamine itself. Acta Med. Okayama 2008, 62, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, G.; Liu, Z.B. Glutamine protects against oxidative stress injury through inhibiting the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in parkinsonian cell model. Environ. Health Prev. 2019, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzili, C.; Otrubova, K.; Boger, D.L. Fatty acid amide signaling molecules. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5959–5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; He, J.Q.; Chen, D.Y.; Pan, Q.L.; Yang, J.F.; Cao, H.C.; Li, L.J. Dynamic changes of key metabolites during liver fibrosis in rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, E.F.; Cardoso, P.B.; Luz, W.L.; Assad, N.; Santos-Silva, M.; Leao, L.K.R.; de Moraes, S.A.S.; Passos, A.D.; Batista, E.D.O.; Oliveira, K.; et al. Putative Activation of Cannabinoid Receptor Type 1 Prevents Brain Oxidative Stress and Inhibits Aggressive-Like Behavior in Zebrafish. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024, 9, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Arias, M.; Navarrete, F.; Blanco-Gandia, M.C.; Arenas, M.C.; Aguilar, M.A.; Bartoll-Andrés, A.; Valverde, O.; Miñarro, J.; Manzanares, J. Role of CB2 receptors in social and aggressive behavior in male mice. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 3019–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, K.A.; Wiley, J.W. The Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Brain-Gut Axis. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzian, A.L.; Drago, F.; Wotjak, C.T.; Micale, V. The dopamine and cannabinoid interaction in the modulation of emotions and cognition: Assessing the role of cannabinoid CB1 receptor in neurons expressing dopamine D1 receptors. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liang, Y.; Hempel, B.; Jordan, C.J.; Shen, H.; Bi, G.H.; Li, J.; Xi, Z.X. Cannabinoid CB1 Receptors Are Expressed in a Subset of Dopamine Neurons and Underlie Cannabinoid-Induced Aversion, Hypoactivity, and Anxiolytic Effects in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acquas, E.; Pisanu, A.; Marrocu, P.; Di Chiara, G. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonists increase rat cortical and hippocampal acetylcholine release in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 401, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathmann, M.; Weber, B.; Zimmer, A.; Schlicker, E. Enhanced acetylcholine release in the hippocampus of cannabinoid CB1 receptor-deficient mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 132, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Harty, S.; Johnson, K.V.A.; Moeller, A.H.; Carmody, R.N.; Lehto, S.M.; Erdman, S.E.; Dunbar, R.I.M.; Burnet, P.W.J. The role of the microbiome in the neurobiology of social behaviour. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1131–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, M.; Shimozawa, A.; Mogi, K.; Kikusui, T. N-Acetyl-D-Mannosamine Treatment Alleviates Age-Related Decline in Place-Learning Ability in Dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2014, 76, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. Sialic Acid Is an Essential Nutrient for Brain Development and Cognition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 29, 177–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.I.; Shin, Y.C.; Lee, J.S.; Yoon, Y.C.; Kim, J.M.; Sung, M.K. N-Acetylglucosamine and its dimer ameliorate inflammation in murine colitis by strengthening the gut barrier function. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 8533–8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.J.; Dew, W.A. Behavioural responses of fathead minnows to carbohydrates found in aquatic environments. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 99, 2040–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cheng, X.X.; Wu, X.F.; Zou, C.Z.; He, B.; Ma, W.Q. Integrated Microbiome and Metabolomics Analysis Reveals Altered Aggressive Behaviors in Broiler Chickens Showing Different Tonic Immobility. Animals 2025, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikusui, T.; Shimozawa, A.; Kitagawa, A.; Nagasawa, M.; Mogi, K.; Yagi, S.; Shiota, K. N-Acetylmannosamine Improves Object Recognition and Hippocampal Cell Proliferation in Middle-Aged Mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 2249–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.F. Mind the fish: Zebrafish as a model in cognitive social neuroscience. Front. Neural Circuits 2013, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, M.O.; Planellas, S.R.; Yang, Y.F.; Phillips, C.; Descovich, K. Emerging indicators of fish welfare in aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, G.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Chen, H.-H.; Qiu, B.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Ding, L.; Jin, P.; Chen, X.-W.-J.; Hou, Z.-S. Neurotransmitter and Gut–Brain Metabolic Signatures Underlying Individual Differences in Sociability in Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Fishes 2025, 10, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120654

Wei G-Y, Zhang Z-X, Chen H-H, Qiu B, Wang Y-Z, Ding L, Jin P, Chen X-W-J, Hou Z-S. Neurotransmitter and Gut–Brain Metabolic Signatures Underlying Individual Differences in Sociability in Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Fishes. 2025; 10(12):654. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120654

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Guan-Yuan, Zheng-Xiang Zhang, Hao-Han Chen, Bao Qiu, Yun-Zhong Wang, Lan Ding, Peng Jin, Xue-Wei-Jie Chen, and Zhi-Shuai Hou. 2025. "Neurotransmitter and Gut–Brain Metabolic Signatures Underlying Individual Differences in Sociability in Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea)" Fishes 10, no. 12: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120654

APA StyleWei, G.-Y., Zhang, Z.-X., Chen, H.-H., Qiu, B., Wang, Y.-Z., Ding, L., Jin, P., Chen, X.-W.-J., & Hou, Z.-S. (2025). Neurotransmitter and Gut–Brain Metabolic Signatures Underlying Individual Differences in Sociability in Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Fishes, 10(12), 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120654