Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Multi-Scale Fishing Effort of Squid Jigging Fleets in the Southeast Pacific Ocean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Data Preprocessing

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Identification of Fishing Vessel Operational Status

2.4. Spatiotemporal Patterns

2.5. Spatial Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Global Moran’s Index Parameter Calculation

2.5.2. Hotspot Analysis Parameter Calculation

3. Results and Analysis

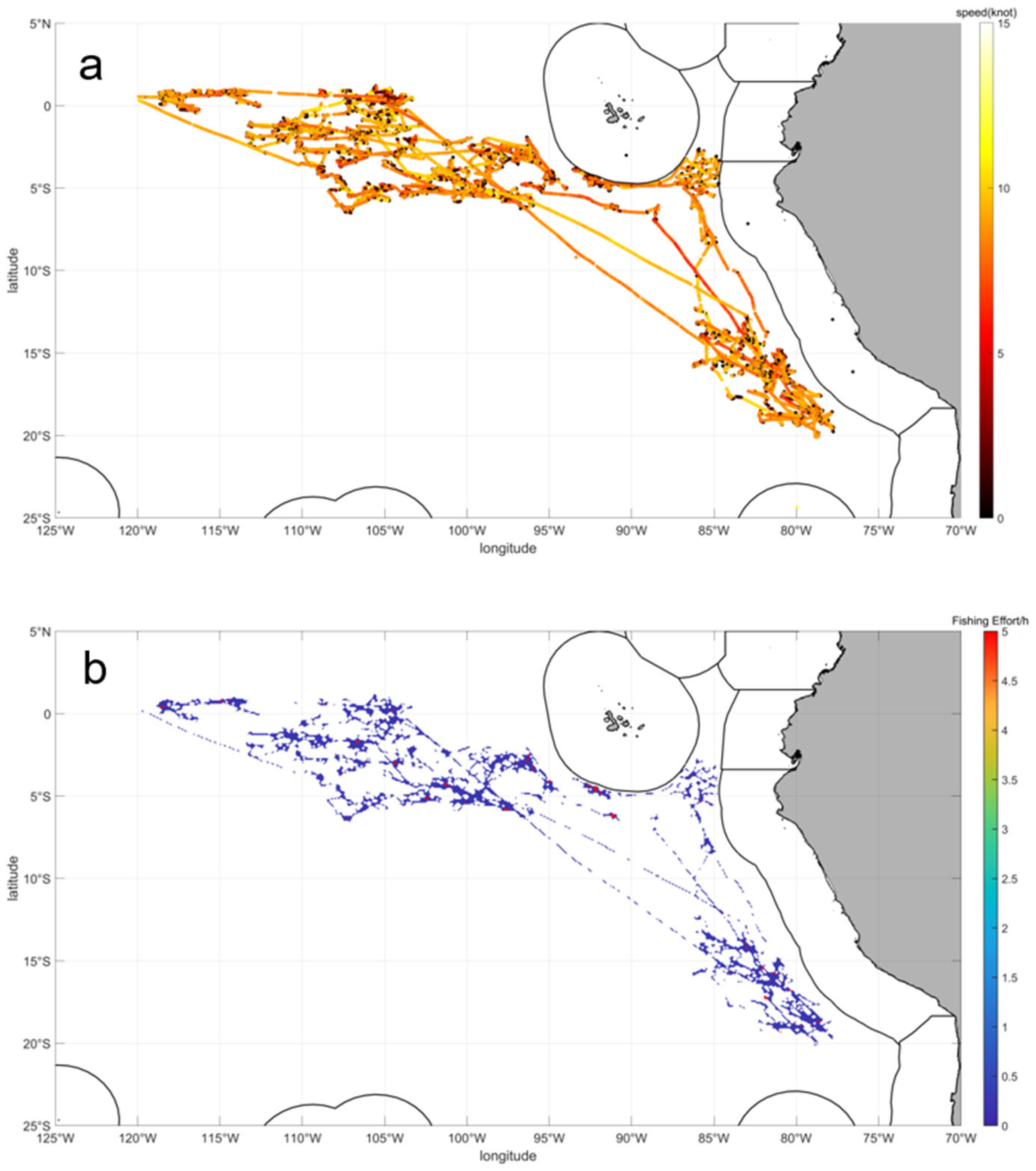

3.1. Analysis of Individual Vessel Fishing Behavior

3.2. Vessel Speed Analysis

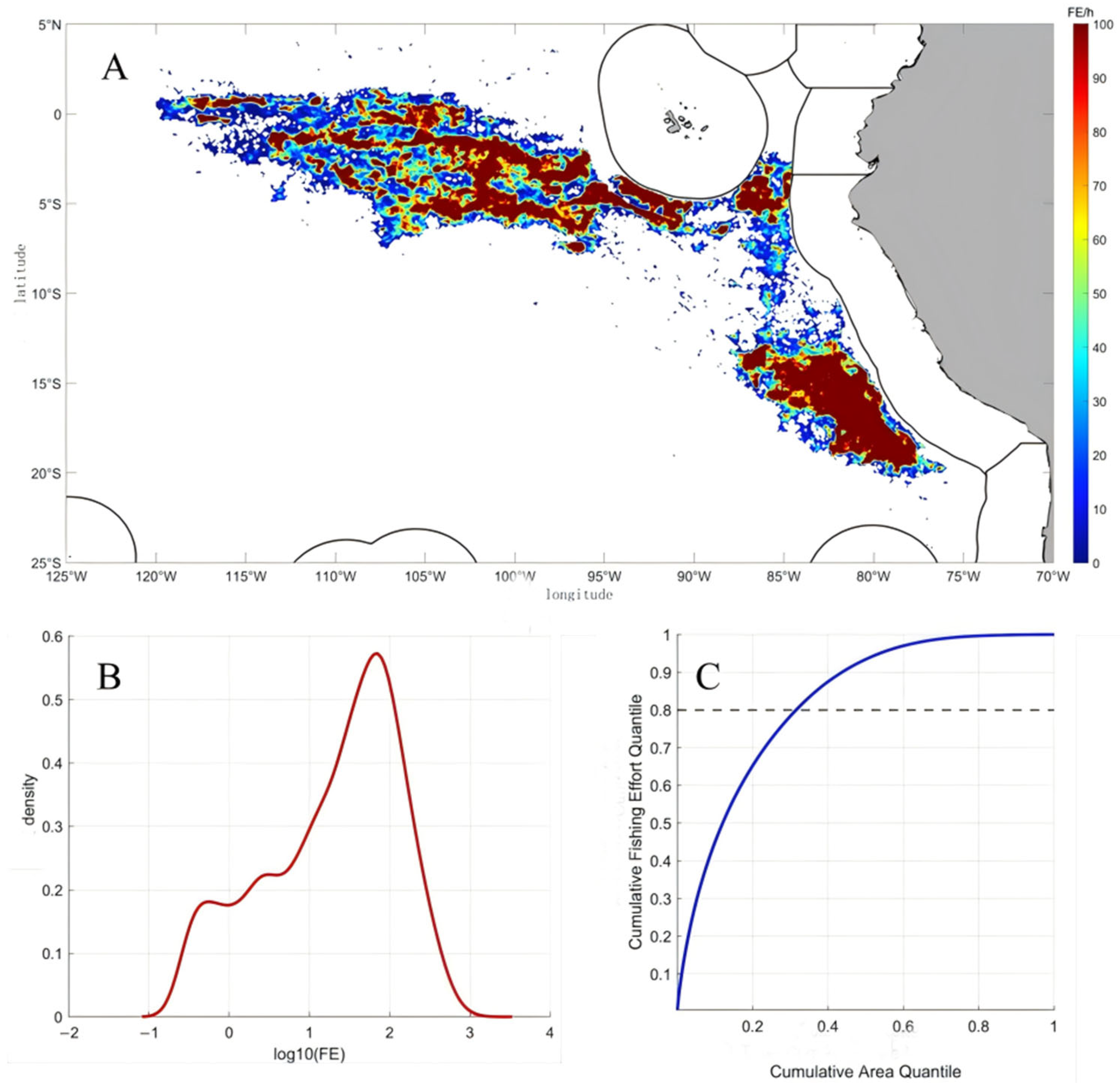

3.3. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Fishing Effort

3.4. Monthly Distribution of Fishing Effort

3.5. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

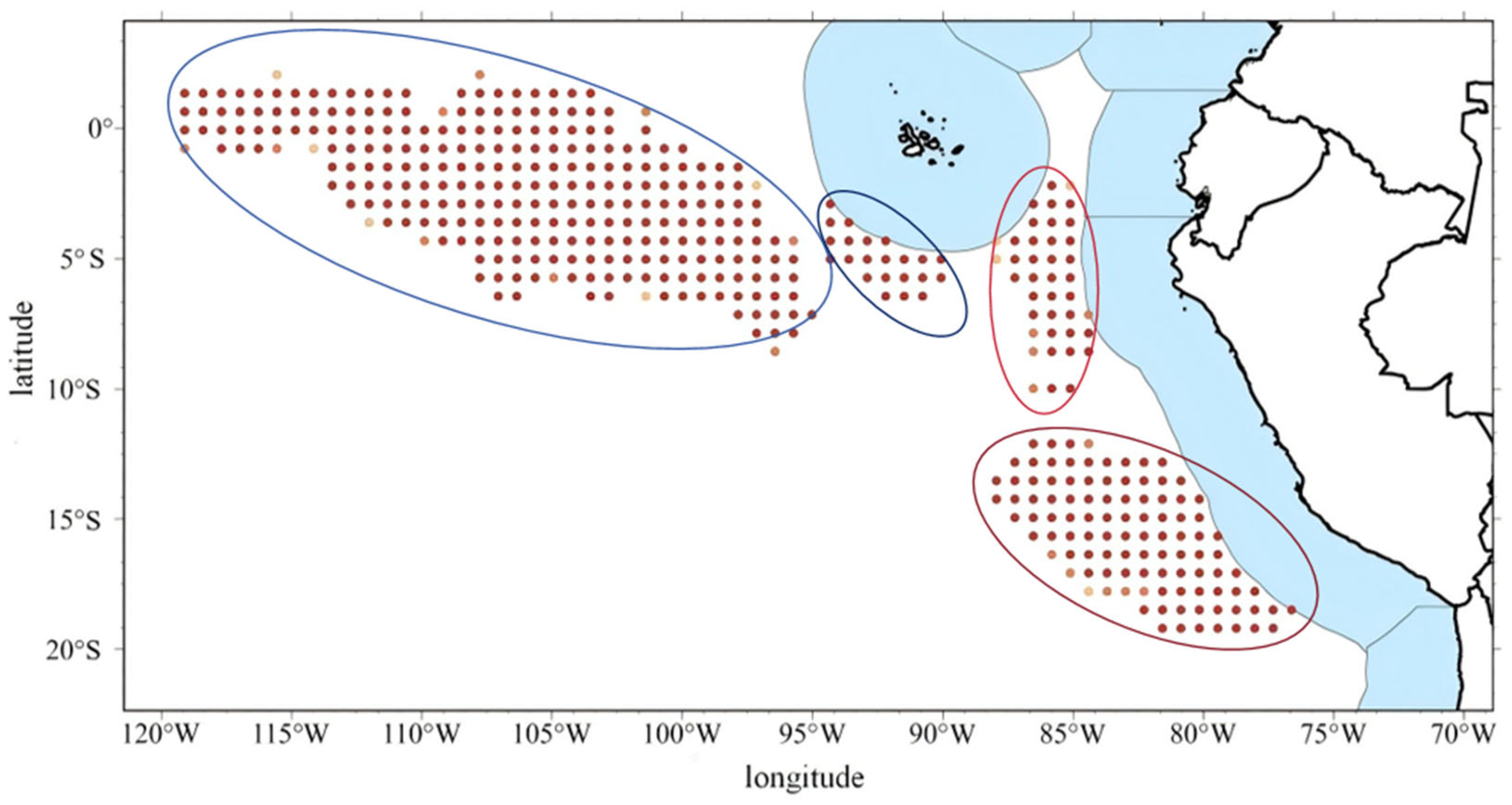

3.5.1. Hotspot Analysis

3.5.2. Hotspot Analysis Global Moran’s Index Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. AIS Data Transmission for Fishing Vessels

4.2. Identification of Fishing Vessel Operational Status

4.3. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Fishing Effort

4.4. Implications for Fishery Management

4.5. Shortcomings and Outlook

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The fleet’s operations showed strong spatiotemporal aggregation, with a small proportion of core fishing grounds (30%) and key fishing days (20%) contributing to the majority (80%) of the total fishing effort. A stable pattern of seasonal cyclic migration between the equatorial fishing grounds and the offshore waters of Peru was observed.

- (2)

- The bimodal distribution of vessel speeds allowed for a clear differentiation between fishing and navigation states, providing methodological support for precise monitoring. The analysis confirmed that during the seasonal fishing moratorium, the Chinese fleet strictly complied with the fishing ban regulations, with no fishing activities detected within the prohibited zones.

- (3)

- The clearly defined fishing hotspots indicate priority areas for implementing spatially differentiated management and protecting critical habitats. Meanwhile, the intensive activities observed near Exclusive Economic Zone boundaries highlight the need for ongoing strengthened surveillance to mitigate potential transboundary risks, providing direct evidence for refined management and risk prevention.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Chen, X. Geographical distribution variations of humboldt squid habitat in the eastern pacific ocean. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2023, 9, 0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wu, Z.; Cui, X.; Fan, W.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, G.; Tang, F. Spatial temporal patterns of chub mackerel fishing ground in the northwest pacific based on spatial autocorrelation model. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2022, 44, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, K.L.; Miller, N.A.; Kroodsma, D.; Hanich, Q.; Miyahara, M.; Saito, R.; Boerder, K.; Tsuda, M.; Oozeki, Y.; Urrutia, S.O. Fishing through the cracks: The unregulated nature of global squid fisheries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, X. Spatial distribution of fishing ground of jumbo flying squid dosidicus gigas in the equator in eastern pacific ocean. Fish. Sci. 2022, 41, 475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, L.; Chen, F.Z. Wb analysis on the fishery status of squid fishing in the high seas of southeast pacific ocean. J. Zhejiang Ocean Univ. 2022, 41, 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Feng, X.; Wen, J.; Wu, X.; Fang, X.; Cui, J.; Feng, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, B.; et al. The potential impacts of climate change on the life history and habitat of jumbo flying squid in the southeast Pacific Ocean: Overview and implications for fisheries management. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2025, 35, 707–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovici, M.; dos Santos, R.A.; Bainy, M.C.; Fischer, L.G.; Cardoso, L.G. Abundance, distribution and population dynamics of the short fin squid Illex argentinus in Southeastern and Southern Brazil. Fish. Res. 2014, 152, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroodsma, D.; Miller, N.A.; Hochberg, T.; Park, J.; Clavelle, T. Ais-based methods for estimating fishing vessel activity and operations. Glob. Atlas AIS-Based Fish. Act. 2019, 13. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca7012en/ca7012en.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Natale, F.; Gibin, M.; Alessandrini, A.; Vespe, M.; Paulrud, A. Mapping fishing effort through AIS data. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taconet, M.; Kroodsma, D.; Fernandes, J. Global Atlas of Ais-Based Fishing Activity; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mirelis, G.; Lindegarth, M.; Sköld, M. Using vessel monitoring system data to improve systematic conservation planning of a multiple-use marine protected area, the kosterhavet national park (Sweden). Ambio 2014, 43, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Zuo, G.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, J. Exploring nighttime fishing and its impact factors in the northwestern south China sea for sustainable fisheries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Gao, Z. Identifying the key factors influencing spatial and temporal variations of regional coastal fishing activities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 248, 106940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Yang, S.; Fan, W.; Shi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, S. Relationship between the spatial and temporal distribution of squid-jigging vessels operations and marine environment in the north pacific ocean. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fei, Y.; Yu, L.; Tang, F.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, T.; Fan, W.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, K. The environmental niche of the squid-jigging fleet in the North Pacific Ocean based on automatic identification system data. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, W. Modeling the potential distribution of Argentine shortfin squid in the southwest Atlantic Ocean. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 43, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Li, Y.; Jiang, K.; Han, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y. Environmental influences on Illex argentinus trawling grounds in the southwest Atlantic high seas. Fishes 2024, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, W.; Yu, L.; Wang, F.; Wu, Z.; Shi, J.; Cui, X.; Cheng, T.; Jin, W.; Wang, G.; et al. Analysis of multi-scale effects and spatial heterogeneity of environmental factors influencing purse seine tuna fishing activities in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Fei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, W.; et al. Spatio-temporal variability of fishing habitat suitability to tuna purse seine fleet in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 70, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, W.; Cui, X.; Zhang, B.; Fan, W. Calculating the fishing effort of longline fishing vessel in the western and central pacific ocean using ais. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kroodsma, D.A.; Mayorga, J.; Hochberg, T.; Miller, N.A.; Boerder, K.; Ferretti, F.; Wilson, A.; Bergman, B.; White, T.D.; Block, B.A.; et al. Tracking the global footprint of fisheries. Science 2018, 359, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Cui, G.; Li, Z.; Wei, Q.; Tao, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, F.; Chen, X.; Zhu, W. Distribution and environmental dependency of small schools of squid dosidicus gigas and in the equator of eastern pacific ocean. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2022, 53, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, B.; Chen, Y. A review of the development of Chinese distant-water squid jigging fisheries. Fish. Res. 2008, 89, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’aNa, R.; Kinas, P.G.; de Miranda, L.V.; Schwingel, P.R.; Castello, J.P.; Vieira, J.P. Bayesian state-space models with multiple CPUE data: The case of a mullet fishery. Sci. Mar. 2017, 81, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, G.; Brown, J.; Soule, B.; Boluda, P.T.; Rogers, A.D. Satellite surveillance of fishing vessel activity in the Ascension Island Exclusive Economic Zone and Marine Protected Area. Mar. Policy 2019, 101, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robards, M.D.; Silber, G.; Adams, J.; Arroyo, J.; Lorenzini, D.; Schwehr, K.; Amos, J. Conservation science and policy applications of the marine vessel Automatic Identification System (AIS)—A review. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2016, 92, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawruch, R. Study reliability of the information about the CPA and TCPA indicated by the ship’s AIS. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2016, 10, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, T.; Kalikoski, D.; Pramod, G.; Short, K. Not honouring the code. Nature 2009, 457, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.M.; McClean, C.J.; Veron, J.E.N.; Hawkins, J.P.; Allen, G.R.; McAllister, D.E.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Schueler, F.W.; Spalding, M.; Wells, F.; et al. Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 2002, 295, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.B.; Close, C. Local knowledge assessment for a small-scale fishery using geographic information systems. Fish. Res. 2007, 83, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | Mean | Stdev | CV | Var | SKEW | KURT | Global Moran’s I | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.757 | 1.618 | 2.137 | 2.619 | 31.413 | 1620.878 | 0.144 | 21.444 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.678 | 1.439 | 2.122 | 2.069 | 23.559 | 926.036 | 0.074 | 10.356 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.604 | 0.910 | 1.506 | 0.827 | 10.143 | 180.706 | 0.134 | 17.116 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.599 | 1.138 | 1.899 | 1.295 | 18.745 | 684.172 | 0.132 | 17.548 | 0 |

| 5 | 0.645 | 1.025 | 1.589 | 1.051 | 6.989 | 78.125 | 0.204 | 25.691 | 0 |

| 6 | 0.572 | 0.802 | 1.403 | 0.643 | 5.352 | 44.328 | 0.289 | 31.606 | 0 |

| 7 | 0.556 | 0.844 | 1.518 | 0.712 | 9.343 | 153.875 | 0.205 | 21.425 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.530 | 0.738 | 1.393 | 0.545 | 9.341 | 161.095 | 0.163 | 15.492 | 0 |

| 9 | 0.622 | 1.142 | 1.837 | 1.303 | 8.672 | 115.104 | 0.183 | 19.085 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.545 | 1.169 | 2.147 | 1.367 | 14.293 | 323.269 | 0.162 | 14.931 | 0 |

| 11 | 0.600 | 0.937 | 1.563 | 0.879 | 7.797 | 92.764 | 0.198 | 22.136 | 0 |

| 12 | 0.565 | 0.930 | 1.645 | 0.864 | 8.527 | 114.369 | 0.179 | 23.060 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, W.; Yang, S. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Multi-Scale Fishing Effort of Squid Jigging Fleets in the Southeast Pacific Ocean. Fishes 2025, 10, 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120637

Shi J, Zhang Y, Shi Y, Li G, Wang W, Yang S. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Multi-Scale Fishing Effort of Squid Jigging Fleets in the Southeast Pacific Ocean. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):637. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120637

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Jiashu, Yu Zhang, Yongchuang Shi, Guangyao Li, Wei Wang, and Shenglong Yang. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Multi-Scale Fishing Effort of Squid Jigging Fleets in the Southeast Pacific Ocean" Fishes 10, no. 12: 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120637

APA StyleShi, J., Zhang, Y., Shi, Y., Li, G., Wang, W., & Yang, S. (2025). Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Multi-Scale Fishing Effort of Squid Jigging Fleets in the Southeast Pacific Ocean. Fishes, 10(12), 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120637