Biomarker Responses and Trophic Dynamics of Metal(loid)s in Prussian Carp and Great Cormorant: Mercury Biomagnifies; Arsenic and Selenium Biodilute

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (I)

- biomarkers of enzymatic activity and oxidative stress would display tissue- and fraction-specific changes in response to exposure to metal(loid)s.

- (II)

- Hg would exhibit elevated tissue-specific metal concentration ratios as a proxy for recent trophic exposure (i.e., higher concentrations in Great Cormorant nestlings compared to Prussian carp);

- (III)

- As and Se would exhibit decreased tissue-specific metal concentration ratios as a proxy for recent trophic exposure (i.e., lower levels in Great Cormorant nestlings relative to the Prussian carp).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Species

2.3. Sampling Procedure

2.4. Chemicals

2.5. Metalloid and Heavy Metal Analyses

2.6. Enzymatic Biomarker Assays

2.7. Non-Enzymatic Biomarker Assays

2.8. Data Analysis

2.8.1. Modelling Biomarker Responses Across Tissues, Fractions, and Years

2.8.2. Modelling Within-Species Exposure–Response Interactions

2.8.3. Tissue-Specific Metal Concentration Ratio (TSMCR) Estimation

3. Results

3.1. Biomarker Responses Across Tissues, Fractions, and Years

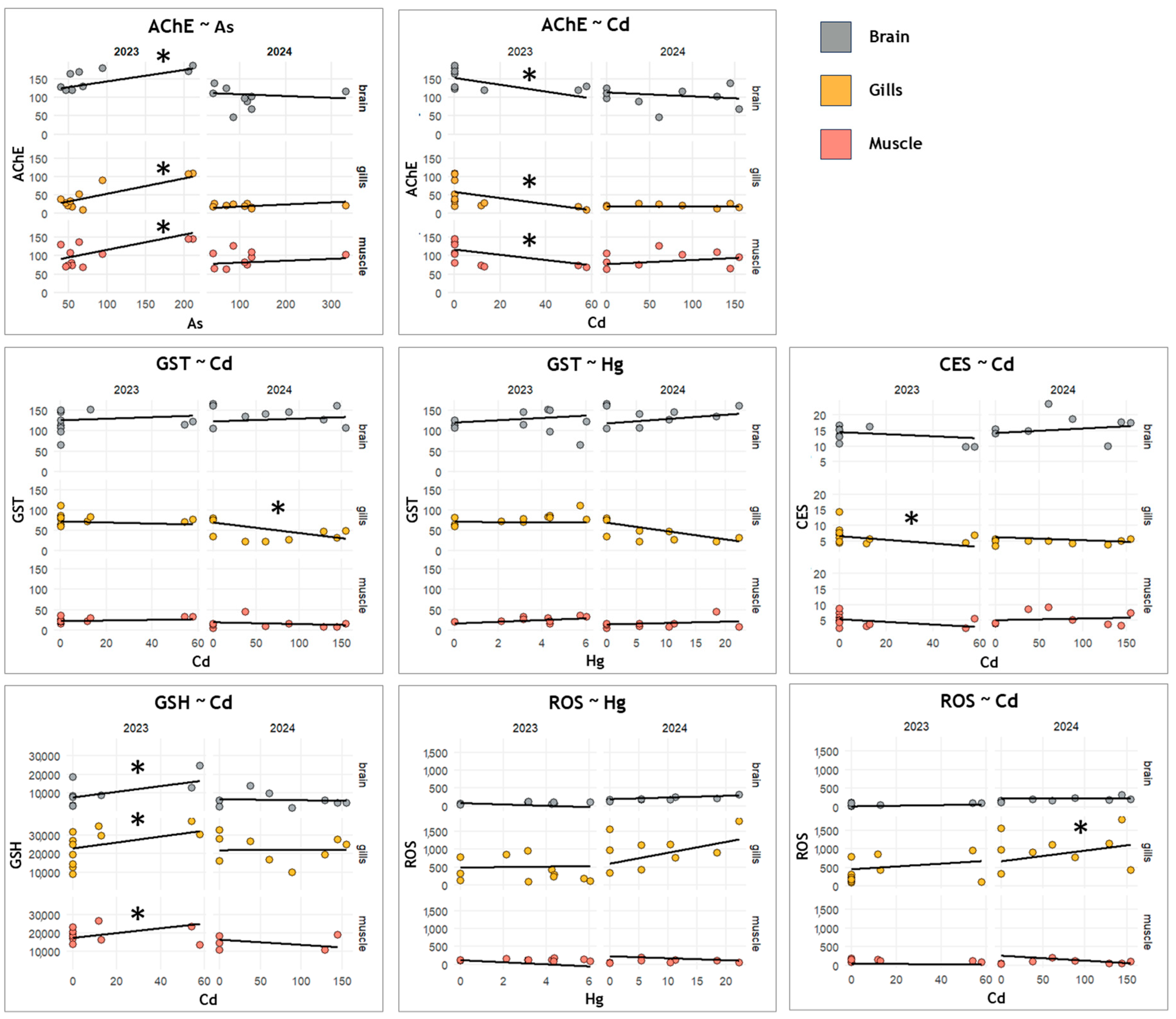

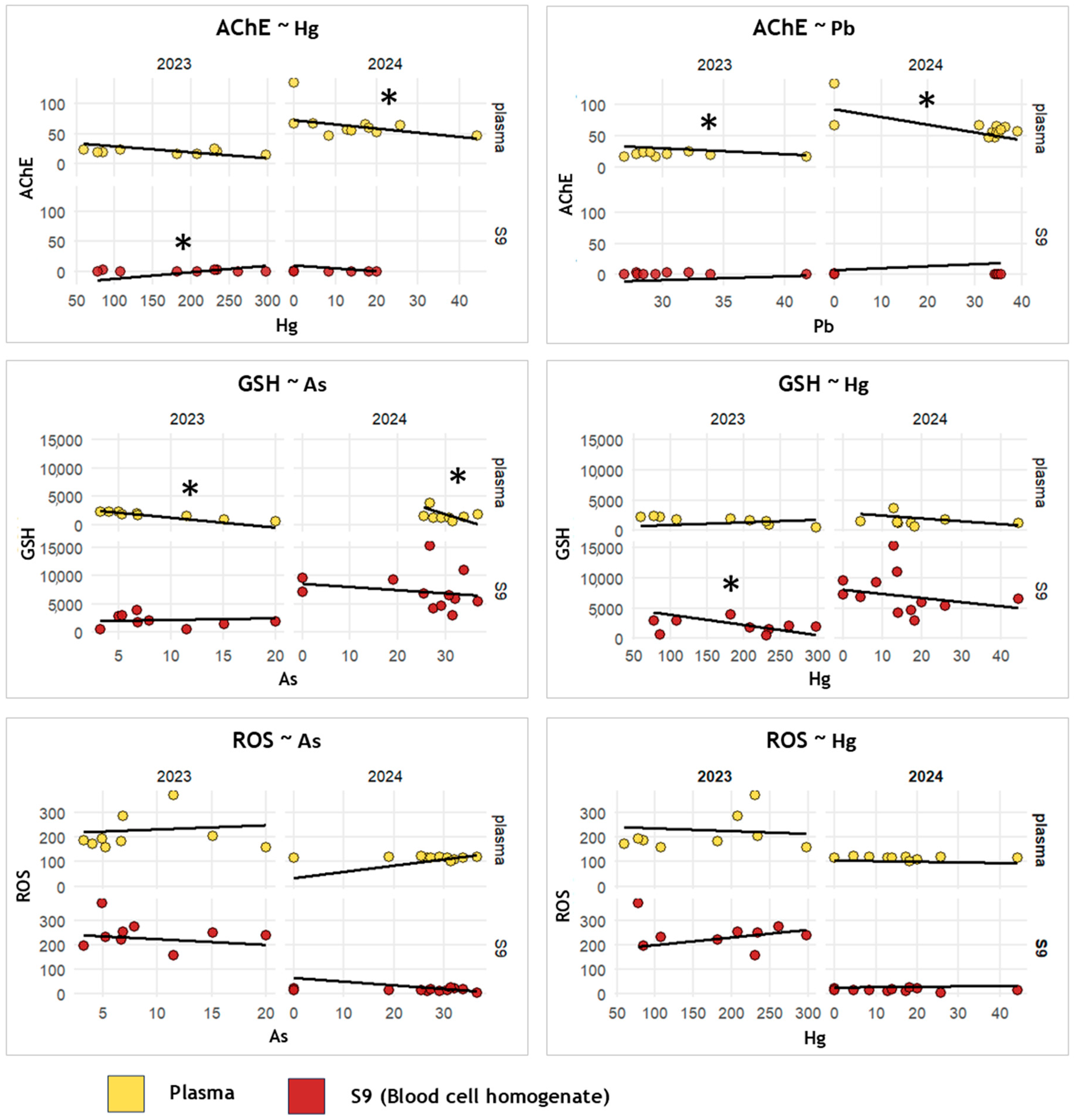

3.2. Within-Species Exposure–Response Interactions

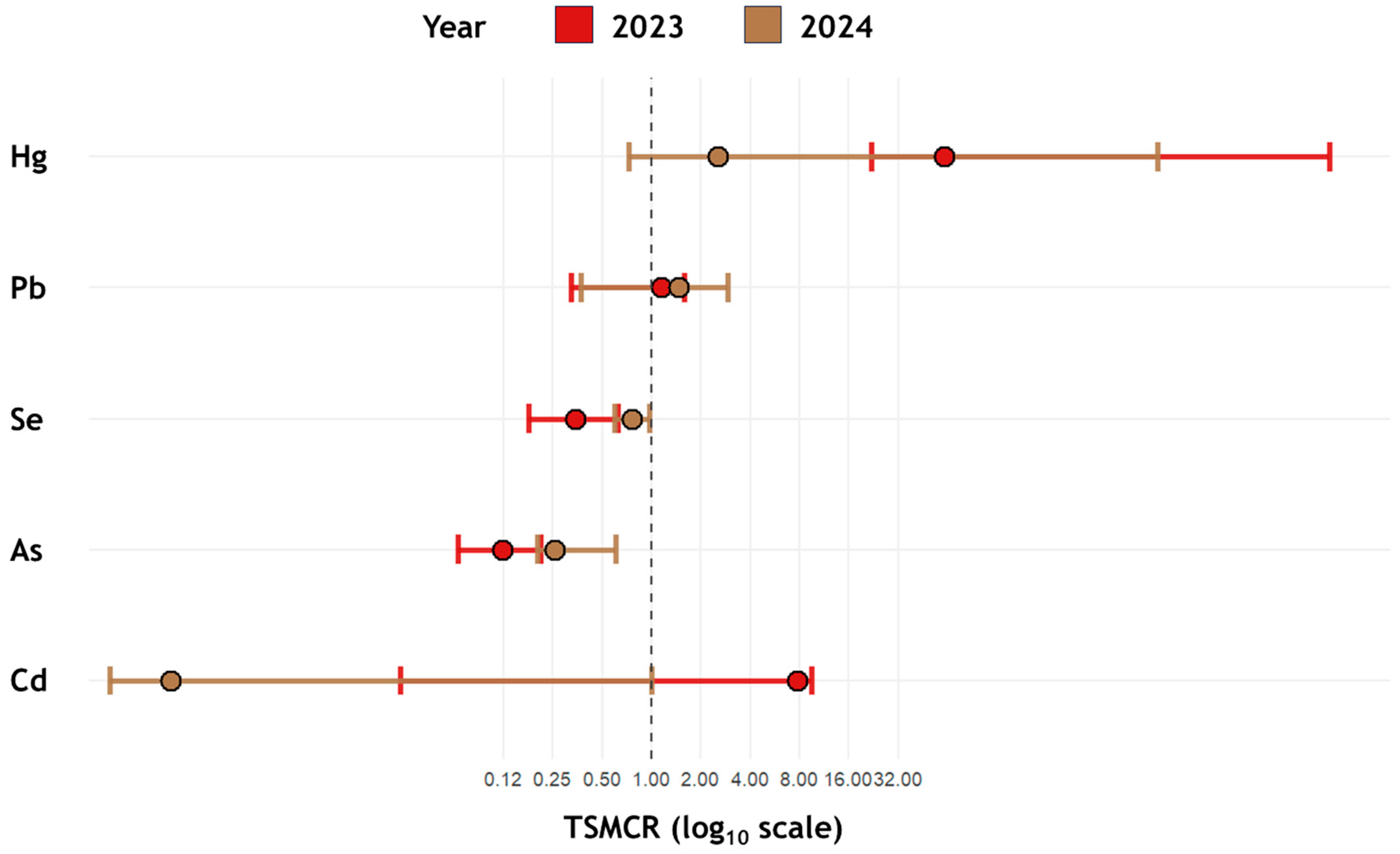

3.3. Trophic Transfer and Bioaccumulation Dynamics

4. Discussion

4.1. Species-, Tissue- and Fraction-Specific Biomarker Response

4.2. Metal(loid) Exposure–Response Patterns

4.3. Trophic Transfer and Bioaccumulation Dynamics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A.H.; Gessner, M.O.; Kawabata, Z.; Knowler, D.J.; Lévêque, C.; Naiman, R.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M.L.J.; et al. Freshwater Biodiversity: Importance, Threats, Status and Conservation Challenges. Biol. Rev. 2006, 81, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangloff, M.M.; Edgar, G.J.; Wilson, B. Imperilled Species in Aquatic Ecosystems: Emerging Threats, Management and Future Prognoses. Aquat. Conserv. 2016, 26, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Turić, N.; Mikuška, A.; Vignjević, G.; Kovačić, L.S.; Pavičić, A.M.; Toth Jakeljić, L.; Velki, M. The Diving Beetle, Cybister lateralimarginalis (De Geer, 1774), as a Bioindicator for Subcellular Changes Affected by Heavy Metal(loid) Pollution in Freshwater Ecosystems. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 279, 107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogidi, O.I.; Akpan, U.M. Aquatic Biodiversity Loss: Impacts of Pollution and Anthropogenic Activities and Strategies for Conservation; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Kant, R.; Sharma, A.K.; Sharma, A.K. Exploring the Impact of Heavy Metals Toxicity in the Aquatic Ecosystem. Int. J. Energy Water Resour. 2025, 9, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Ilahi, I. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology of Hazardous Heavy Metals: Environmental Persistence, Toxicity, and Bioaccumulation. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 6730305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.I.; Samuel, P.O.; Oloni, G.O.; Ezekiel, G.O.; Ikpekoro, V.O.; Obasohan, P.; Ongulu, J.; Otunuya, C.F.; Opiti, A.R.; Ajakaye, R.S.; et al. Environmental Persistence, Bioaccumulation, and Ecotoxicology of Heavy Metals. Chem. Ecol. 2024, 40, 322–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E. Trophic Transfer, Bioaccumulation, and Biomagnification of Non-Essential Hazardous Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Food Chains/Webs—Concepts and Implications for Wildlife and Human Health. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2018, 25, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, U.; Kafeel, U.; Naikoo, M.I.; Kaifiyan, M.; Hasan, M.; Khan, F.A. Trophic Transfer, Bioaccumulation, and Detoxification of Lead and Zinc via Sewage Sludge Applied Soil-Barley-Aphid-Ladybird Food Chain. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2023, 234, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, A. Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer of Heavy Metals in Marine Fish: Ecological and Ecosystem-Level Impacts. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidon, N.B.; Szabó, R.; Budai, P.; Lehel, J. Trophic Transfer and Biomagnification Potential of Environmental Contaminants (Heavy Metals) in Aquatic Ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 340, 122815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja-Echevarría, L.M.; Marmolejo-Rodríguez, A.J.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R.; Tripp-Valdéz, A.; Tamburin, E.; Lara, A.; Jonathan, M.P.; Sujitha, S.B.; Delgado-Huertas, A.; et al. Trophic Structure and Biomagnification of Cadmium, Mercury and Selenium in Brown Smooth Hound Shark (Mustelus henlei) within a Trophic Web. Food Webs 2023, 34, e00263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiard, J.C.; Amiard-Triquet, C.; Berthet, B.; Metayer, C. Comparative Study of the Patterns of Bioaccumulation of Essential (Cu, Zn) and Non-Essential (Cd, Pb) Trace Metals in Various Estuarine and Coastal Organisms. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1987, 106, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, M.S.; Venkatraman, S.K.; Vijayakumar, N.; Kanimozhi, V.; Arbaaz, S.M.; Stacey, R.G.S.; Anusha, J.; Choudhary, R.; Lvov, V.; Tovar, G.I.; et al. Bioaccumulation of Lead (Pb) and Its Effects on Human: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczyńska, J.; Paszczyk, B.; Łuczyński, M.J. Fish as a Bioindicator of Heavy Metals Pollution in Aquatic Ecosystem of Pluszne Lake, Poland, and Risk Assessment for Consumer’s Health. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 153, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, I.; Mariottini, M.; Sensini, C.; Lancini, L.; Focardi, S. Fish as Bioindicators of Brackish Ecosystem Health: Integrating Biomarker Responses and Target Pollutant Concentrations. Oceanol. Acta 2003, 26, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Domínguez, C.; Bjedov, D.; Buelvas-Soto, J.; Córdoba-Tovar, L.; Bernal-Alviz, J.; Marrugo-Negrete, J. Factors Affecting Arsenic and Mercury Accumulation in Fish from the Colombian Caribbean: A Multifactorial Approach Using Machine Learning. Environ. Res. 2025, 268, 120761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal-Alviz, J.; Córdoba-Tovar, L.; Pastrana-Durango, D.; Molina-Polo, C.; Buelvas-Soto, J.; Cruz-Esquivel, Á.; Marrugo-Negrete, J.; Díez, S. Influence of Environmental and Biological Factors on Mercury Accumulation in Fish from the Atrato River Basin, Colombia. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Mikuška, A.; Velki, M.; Lončarić, Z.; Mikuška, T. The First Analysis of Heavy Metals in the Grey Heron Ardea cinerea Feathers from the Croatian Colonies. Larus Godišnjak Zavoda Za Ornitol. Hrvat. Akad. Znan. I Umjet. 2020, 55, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Mikuska, A.; Begović, L.; Bollinger, E.; Bustnes, J.O.; Deme, T.; Mikuška, T.; Morocz, A.; Schulz, R.; Søndergaard, J.; et al. Effects of White-Tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) Nestling Diet on Mercury Exposure Dynamics in Kopački Rit Nature Park, Croatia. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehel, J.; Grúz, A.; Bartha, A.; Menyhárt, L.; Szabó, R.; Tibor, K.; Budai, P. Potentially Toxic Elements in Different Tissues of Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) at a Wetland Area. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 120540–120551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, R.K.; Eulaers, I.; Laaksonen, T.; Vasko, V.; Jormalainen, V. White-Tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) and Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) Nestlings as Spatial Sentinels of Baltic Acidic Sulphate Soil Associated Metal Contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opačak, A.; Florijančić, T.; Horvat, D.; Ozimec, S.; Bodakoš, D. Diet Spectrum of Great Cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis L.) at the Donji Miholjac Carp Fishponds in Eastern Croatia. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2004, 50, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoric, S.; Visnjić-Jeftic, Z.; Jaric, I.; Djikanovic, V.; Mickovic, B.; Nikcevic, M.; Lenhardt, M. Accumulation of 20 Elements in Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) and Its Main Prey, Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) and Prussian Carp (Carassius gibelio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 80, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošković, A.; Stojković Piperac, M.; Kojadinović, N.; Radenković, M.; Đuretanović, S.; Čerba, D.; Milošević, Đ.; Simić, V. Potentially Toxic Elements in Invasive Fish Species Prussian Carp (Carassius gibelio) from Different Freshwater Ecosystems and Human Exposure Assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 29152–29164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opačak, A.; Jelkić, D. Seasonal Changes in the Condition Factor and Gonado-Somatic Index of Carassius gibelio from the Kopački Rit Nature Park, Croatia. Poljoprivreda 2023, 29, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peršić, V.; Čerba, D.; Bogut, I.; Horvatić, J. Trophic State and Water Quality in the Danube Floodplain Lake (Kopački Rit Nature Park, Croatia) in Relation to Hydrological Connectivity. In Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Stojković Piperac, M.; Milošević, D.; Čerba, D.; Simić, V. Fish Communities Over the Danube Wetlands in Serbia and Croatia. In Small Water Bodies of the Western Balkans; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, W.P.; Mutti, A. Role of Biomarkers in Monitoring Exposures to Chemicals: Present Position, Future Prospects. Biomarkers 2004, 9, 211–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, F.; Pla, A. Biomarkers as Biological Indicators of Xenobiotic Exposure. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2001, 21, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Velki, M.; Toth, L.; Filipović Marijić, V.; Mikuška, T.; Jurinović, L.; Ečimović, S.; Turić, N.; Lončarić, Z.; Šariri, S.; et al. Heavy Metal(loid) Effect on Multi-Biomarker Responses in Apex Predator: Novel Assays in the Monitoring of White Stork Nestlings. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 324, 121398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Cao, J.; Qin, X.; Qiu, W.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Toxic Effects on Bioaccumulation, Hematological Parameters, Oxidative Stress, Immune Responses and Tissue Structure in Fish Exposed to Ammonia Nitrogen: A Review. Animals 2021, 11, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Z.-H. Neurotoxicity and Physiological Stress in Brain of Zebrafish Chronically Exposed to Tributyltin. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2021, 84, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukharenko, E.V.; Samoylova, I.V.; Nedzvetsky, V.S. Molecular Mechanisms of Aluminium Ions Neurotoxicity in Brain Cells of Fish from Various Pelagic Areas. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2017, 8, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.H.; Piermarini, P.M.; Choe, K.P. The Multifunctional Fish Gill: Dominant Site of Gas Exchange, Osmoregulation, Acid-Base Regulation, and Excretion of Nitrogenous Waste. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 97–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Boman, J. Biomonitoring of Trace Elements in Muscle and Liver Tissue of Freshwater Fish. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2003, 58, 2215–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, S.; Andevski, J.; Duke, G.; Eulaers, I.; Gómez-Ramírez, P.; Hallgrimsson, G.T.; Helander, B.; Herzke, D.; Jaspers, V.L.B.; Krone, O.; et al. A Schematic Sampling Protocol for Contaminant Monitoring in Raptors. Ambio 2021, 50, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javna ustanova “Park prirode Kopački rit”. Plan Upravljanja Parkom Prirode Kopački Rit i Pridruženim Zaštićenim Područjem Te Područjima Ekološke Mreže; Javna ustanova “Park prirode Kopački rit”: Kopačevo, Croatia, 2023.

- Horvatić, S.; Zanella, D.; Mustafić, P.; Marčić, Z.; Ćaleta, M.; Buj, I.; Karlović, R.; Ivić, L.; Onorato, L.; Tvrdinić, G.; et al. The Fish Fauna of Nature Park Kopački Rit. In Proceedings of the 11th Symposium with International Participation Kopački Rit: Past, Present, Future 2022, Osijek, Croatia, 29–30 September 2022; Ozimec, S., Bogut, I., Bašić, I., Rožac, V., Stević, F., Popović, Ž., Eds.; Public Institution Nature Park Kopački rit: Kopačevo, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Emmrich, M.; Düttmann, H. Seasonal Shifts in Diet Composition of Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis Foraging at a Shallow Eutrophic Inland Lake. Ardea 2011, 99, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čech, M.; Vejřík, L. Winter Diet of Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) on the River Vltava: Estimate of Size and Species Composition and Potential for Fish Stock Losses. Folia Zool. 2011, 60, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eerden, M.; van Rijn, S.; Volponi, S.; Paquet, J.-Y.; Carss, D. Cormorants and the European Environment: Exploring Cormorant Status and Distribution on a Continental Scale; INTERCAFE COST Action 635 Final Report I; NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology: Gwynedd, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mikuska, T.; Tomik, A.; Ledinšćak, J. Projekt NATURAVITA—Monitoring Staništa, Flore i Faune—Ponovljeni Postupak—Grupa 5: Monitoring Ptica; Fakultet agrobiotehničkih znanosti Osijek: Osijek, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mikuska, T.; Rožac, V.; Šetina, N.; Hima, V. Status of the Breeding Population of Great Cormorants in Croatia in 2012; Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag; DCE–Danish Centre for Environment and Energy: Roskilde, Denmark, 2013; ISBN 978-87-7156-018-3. [Google Scholar]

- EN 14011:2003; Water Quality—Sampling of Fish with Electricity. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- EN 14757:2005; Water quality—Sampling of Fish with Multi-mesh Gillnets. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Dragun, Z.; Krasnići, N.; Ivanković, D.; Filipović Marijić, V.; Mijošek, T.; Redžović, Z.; Erk, M. Comparison of Intracellular Trace Element Distributions in the Liver and Gills of the Invasive Freshwater Fish Species, Prussian Carp (Carassius gibelio Bloch, 1782). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 138923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović Marijić, V.; Krasnići, N.; Valić, D.; Kapetanović, D.; Vardić Smrzlić, I.; Jordanova, M.; Rebok, K.; Ramani, S.; Kostov, V.; Nastova, R.; et al. Pollution Impact on Metal and Biomarker Responses in Intestinal Cytosol of Freshwater Fish. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 63510–63521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijošek, T.; Filipović Marijić, V.; Dragun, Z.; Ivanković, D.; Krasnići, N.; Redžović, Z.; Erk, M. Intestine of Invasive Fish Prussian Carp as a Target Organ in Metal Exposure Assessment of the Wastewater Impacted Freshwater Ecosystem. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Velki, M.; Lackmann, C.; Begović, L.; Mikuška, T.; Jurinović, L.; Mikuška, A. Blood Biomarkers in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings Show Different Responses in Several Areas of Croatia. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 2022, 337, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Velki, M.; Kovačić, L.S.; Begović, L.; Lešić, I.; Jurinović, L.; Mikuska, T.; Sudarić Bogojević, M.; Ečimović, S.; Mikuška, A. White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings Affected by Agricultural Practices? Assessment of Integrated Biomarker Responses. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, D.; Mikuška, A.; Lackmann, C.; Begović, L.; Mikuška, T.; Velki, M. Application of Non-Destructive Methods: Biomarker Assays in Blood of White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Nestlings. Animals 2021, 11, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuška, A.; Alić, S.; Levak, I.; Bernal-Alviz, J.; Velki, M.; Nekić, R.; Ečimović, S.; Bjedov, D. Bayesian Structure Learning Reveals Disconnected Correlation Patterns Between Morphometric Traits and Blood Biomarkers in White Stork Nestlings. Birds 2025, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerzak, L.; Sparks, T.H.; Kasprzak, M.; Bochenski, M.; Kaminski, P.; Wiśniewska, E.; Mroczkowski, S.; Tryjanowski, P. Blood Chemistry in White Stork Ciconia ciconia Chicks Varies by Sex and Age. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 156, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, Å.M.M. Evaluating Blood and Excrement as Bioindicators for Metal Accumulation in Birds. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 233, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, P.-Y.; Le Bayon, N.; Masbou, J.; Delcourt, N.; Chastel, O. Mercury and Other Heavy Metals in Blood and Feathers as Indicators of Tissue Burdens in Songbirds. Ecotoxicology 2015, 24, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Coeurdassier, M.; Fritsch, C.; Faivre, B.; Crini, N.; Scheifler, R. Partitioning of Cd and Pb in the Blood of European Blackbirds (Turdus merula) from a Smelter Contaminated Site and Use for Biomonitoring. Chemosphere 2012, 87, 1368–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V.; Featherstone, R.M. A New and Rapid Colorimetric Determination of Acetylcholinesterase Activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, M.; Satoh, T. Measurement of Carboxylesterase (CES) Activities. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2001, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, W.H.; Jakoby, W.B. Assays for Differentiation of Glutathione S-Transferases. Methods Enzymol. 1981, 77, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrends, R.; Ellis, S.R.; Verhelst, S.H.L.; Kreutz, M.R. Synaptoneurolipidomics: Lipidomics in the Study of Synaptic Function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2025, 50, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, G.; Soreq, H. Termination and beyond: Acetylcholinesterase as a Modulator of Synaptic Transmission. Cell Tissue Res. 2006, 326, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.C. Brain Regional Heterogeneity and Toxicological Mechanisms of Organophosphates and Carbamates. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2004, 14, 103–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.E.; Schönenberger, R.; Hollender, J.; Schirmer, K. Organ-Specific Biotransformation in Salmonids: Insight into Intrinsic Enzyme Activity and Biotransformation of Three Micropollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 925, 171769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.P.M.; Franco, M.E.; Schirmer, K. Comparative Characterization of Organ-Specific Phase I and II Biotransformation Enzyme Kinetics in Salmonid S9 Sub-Cellular Fractions and Cell Lines. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2025, 41, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierbach, A.; Groh, K.J.; Schönenberger, R.; Schirmer, K.; Suter, M.J.-F. Glutathione S-Transferase Protein Expression in Different Life Stages of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 162, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellou, J.; Ross, N.W.; Moon, T.W. Glutathione, Glutathione S-Transferase, and Glutathione Conjugates, Complementary Markers of Oxidative Stress in Aquatic Biota. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2012, 19, 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.H. The Fish Gill: Site of Action and Model for Toxic Effects of Environmental Pollutants. Environ. Health Perspect. 1987, 71, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, R.W.M. Trace Metals in the Teleost Fish Gill: Biological Roles, Uptake Regulation, and Detoxification Mechanisms. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2024, 194, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehrer, J.P. The Haber–Weiss Reaction and Mechanisms of Toxicity. Toxicology 2000, 149, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.M.; Somero, G.N. Enzyme Activities of Fish Skeletal Muscle and Brain as Influenced by Depth of Occurrence and Habits of Feeding and Locomotion. Mar. Biol. 1980, 60, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoruš, D.; Kapelj, S.; Zavrtnik, S.; Leskovar, K. Suspended Sediment Metal and Metalloid Composition in the Danube River Basin, Croatia. Water 2022, 14, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el-Mekawi, S.; Yagil, R.; Meyerstein, N. Effect of Oxidative Stress on Avian Erythrocytes. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1993, 4, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandravanshi, L.P.; Gupta, R.; Shukla, R.K. Arsenic-Induced Neurotoxicity by Dysfunctioning Cholinergic and Dopaminergic System in Brain of Developing Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 189, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medda, N.; Patra, R.; Ghosh, T.K.; Maiti, S. Neurotoxic Mechanism of Arsenic: Synergistic Effect of Mitochondrial Instability, Oxidative Stress, and Hormonal-Neurotransmitter Impairment. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 198, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, D.; Roque, G.M.; de Almeida, E.A. In Vitro and in Vivo Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase and Carboxylesterase by Metals in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Mar. Environ. Res. 2013, 91, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulis, J.-M. Cellular Mechanisms of Cadmium Toxicity Related to the Homeostasis of Essential Metals. BioMetals 2010, 23, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H.; Cha, H.-J.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.-H.; Park, C.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, G.-Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Hwang, H.-J.; et al. Protective Effect of Glutathione against Oxidative Stress-Induced Cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 Macrophages through Activating the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2/Heme Oxygenase-1 Pathway. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballatori, N.; Clarkson, T.W. Biliary Secretion of Glutathione and of Glutathione-Metal Complexes. Toxicol. Sci. 1985, 5, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, K.; Pereira, E.; Duarte, A.C.; Ahmad, I. Glutathione and Its Dependent Enzymes’ Modulatory Responses to Toxic Metals and Metalloids in Fish—A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Carvalho, C.; Bernusso, V.A.; de Araújo, H.S.S.; Espíndola, E.L.G.; Fernandes, M.N. Biomarker Responses as Indication of Contaminant Effects in Oreochromis niloticus. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Kang, J.C. Oxidative Stress, Neurotoxicity, and Non-Specific Immune Responses in Juvenile Red Sea Bream, Pagrus major, Exposed to Different Waterborne Selenium Concentrations. Chemosphere 2015, 135, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, Q.; Abdullah, S.; Naz, H.; Abbas, K.; Shafique, L. Changes in Glutathione S-Transferase Activity and Total Protein Contents of Labeo rohita. Punjab Univ. J. Zool. 2020, 35, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, S.A.; Patwary, M.A.M.; Matin, M.M.; Ghann, W.E.; Uddin, J.; Kazi, M. Interaction of Mercury Species with Proteins: Towards Possible Mechanism of Mercurial Toxicology. Toxicol. Res. 2023, 12, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Imura, N.; Clarkson, T.W. Mechanism of Methylmercury Cytotoxicity. CRC Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1987, 18, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, A.-M.; Taban, J.; Varghese, E.; Alost, B.T.; Moreno, S.; Büsselberg, D. Lead (Pb2+) Neurotoxicity: Ion-Mimicry with Calcium (Ca2+) Impairs Synaptic Transmission. A Review with Animated Illustrations of the Pre- and Post-Synaptic Effects of Lead. J. Local. Glob. Health Sci. 2013, 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suszkiw, J.; Toth, G.; Murawsky, M.; Cooper, G.P. Effects of Pb2+ and Cd2+ on Acetylcholine Release and Ca2+ Movements in Synaptosomes and Subcellular Fractions from Rat Brain and Torpedo Electric Organ. Brain Res. 1984, 323, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, Y.; Sperling, R. The Chemical Identification of S-Hg-S Bonds in Mercury Protein Derivatives. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Protein Struct. 1970, 221, 410–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Virosta, P.; Espín, S.; Ruiz, S.; Panda, B.; Ilmonen, P.; Schultz, S.L.; Karouna-Renier, N.; García-Fernández, A.J.; Eeva, T. Arsenic-Related Oxidative Stress in Experimentally-Dosed Wild Great Tit Nestlings. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, C.C.; Miller, E.K.; McFarland, K.P.; Taylor, R.J.; Faccio, S.D. Mercury Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer in the Terrestrial Food Web of a Montane Forest. Ecotoxicology 2009, 19, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjedov, D.; Bernal-Alviz, J.; Buelvas-Soto, J.A.; Jurman, L.A.; Marrugo-Negrete, J.L. Elevated Heavy Metal(loid) Blood and Feather Concentrations in Wetland Birds from Different Trophic Levels Indicate Exposure to Environmental Pollutants. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 87, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.A.; Roden, E.E.; Bonzongo, J.-C. Microbial Mercury Transformation in Anoxic Freshwater Sediments under Iron-Reducing and Other Electron-Accepting Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, J.T.; Peterson, S.H.; Herzog, M.P.; Yee, J.L. Methylmercury Effects on Birds: A Review, Meta-Analysis, and Development of Toxicity Reference Values for Injury Assessment Based on Tissue Residues and Diet. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 43, 1195–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anne Albert, C. Uptake, Elimination and Toxicity of an Arsenic-Based Pesticide in an Avian System. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada, June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, M.; Verhagen, I.; Viitaniemi, H.M.; Laine, V.N.; Visser, M.E.; Husby, A.; van Oers, K. Temporal Changes in DNA Methylation and RNA Expression in a Small Song Bird: Within- and between-Tissue Comparisons. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luvonga, C.; Rimmer, C.A.; Yu, L.L.; Lee, S.B. Organoarsenicals in Seafood: Occurrence, Dietary Exposure, Toxicity, and Risk Assessment Considerations—A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Yang, Z. The Dynamic Effects of Different Inorganic Arsenic Species in Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus) Liver during Chronic Dietborne Exposure: Bioaccumulation, Biotransformation and Oxidative Stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Roh, Y.J.; Han, S.-J.; Park, I.; Lee, H.M.; Ok, Y.S.; Lee, B.C.; Lee, S.-R. Role of Selenoproteins in Redox Regulation of Signaling and the Antioxidant System: A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.K.; Wang, F. Mercury-Selenium Compounds and Their Toxicological Significance: Toward a Molecular Understanding of the Mercury-Selenium Antagonism. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, C.D.; Liu, J.; Choudhuri, S. Metallothionein: An Intracellular Protein to Protect against Cadmium Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999, 39, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.-E.; Larsson, Å.; Maage, A.; Haux, C.; Bonham, K.; Zafarullah, M.; Gedamu, L. Induction of Metallothionein Synthesis in Rainbow Trout, Salmo gairdneri, during Long-Term Exposure to Waterborne Cadmium. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1989, 6, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włostowski, T.; Dmowski, K.; Bonda-Ostaszewska, E. Cadmium Accumulation, Metallothionein and Glutathione Levels, and Histopathological Changes in the Kidneys and Liver of Magpie (Pica pica) from a Zinc Smelter Area. Ecotoxicology 2010, 19, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneda, S.; Suzuki, K.T. Detoxification of Mercury by Selenium by Binding of Equimolar Hg–Se Complex to a Specific Plasma Protein. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997, 143, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, D.A.; Welbourn, P.M. Cadmium in the Aquatic Environment: A Review of Ecological, Physiological, and Toxicological Effects on Biota. Environ. Rev. 1994, 2, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciosek, Ż.; Kot, K.; Kosik-Bogacka, D.; Łanocha-Arendarczyk, N.; Rotter, I. The Effects of Calcium, Magnesium, Phosphorus, Fluoride, and Lead on Bone Tissue. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bjedov, D.; Lončarić, Ž.; Ečimović, S.; Mikuška, A.; Alić, S.; Bernal-Alviz, J.; Turić, N.; Marčić, Z.; Nekić, R.; Kovačić, L.S.; et al. Biomarker Responses and Trophic Dynamics of Metal(loid)s in Prussian Carp and Great Cormorant: Mercury Biomagnifies; Arsenic and Selenium Biodilute. Fishes 2025, 10, 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120635

Bjedov D, Lončarić Ž, Ečimović S, Mikuška A, Alić S, Bernal-Alviz J, Turić N, Marčić Z, Nekić R, Kovačić LS, et al. Biomarker Responses and Trophic Dynamics of Metal(loid)s in Prussian Carp and Great Cormorant: Mercury Biomagnifies; Arsenic and Selenium Biodilute. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):635. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120635

Chicago/Turabian StyleBjedov, Dora, Željka Lončarić, Sandra Ečimović, Alma Mikuška, Sabina Alić, Jorge Bernal-Alviz, Nataša Turić, Zoran Marčić, Rocco Nekić, Lucija Sara Kovačić, and et al. 2025. "Biomarker Responses and Trophic Dynamics of Metal(loid)s in Prussian Carp and Great Cormorant: Mercury Biomagnifies; Arsenic and Selenium Biodilute" Fishes 10, no. 12: 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120635

APA StyleBjedov, D., Lončarić, Ž., Ečimović, S., Mikuška, A., Alić, S., Bernal-Alviz, J., Turić, N., Marčić, Z., Nekić, R., Kovačić, L. S., Marković, T., & Velki, M. (2025). Biomarker Responses and Trophic Dynamics of Metal(loid)s in Prussian Carp and Great Cormorant: Mercury Biomagnifies; Arsenic and Selenium Biodilute. Fishes, 10(12), 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120635