1. Introduction

This will be an account of women looking. It will linger with sight for some time. In the name of some corporeal feminine, women are often aligned with the other senses besides sight (and some align themselves). Feeling, hearing and tasting: if women look under the sign of an embodied feminine, then that glance is often attached—sensuously, synaesthetically—to the hand, the ear or the mouth. As important as this has been for a feminist approach to art, film and literature, I am not interested in a multisensorial mode of vision here. I am writing about women looking—with an emphasis on what we can see.

I am not mounting a manifesto for a female gaze to combat the male one of 1970s psychoanalytic theory. This will be an account of looking that is invested in feminist thought of what is sometimes known as ‘the long 1970s’ (that much is true), but little about sight as it is outlined here is essential to women. It is shared by women, but not exclusively. While I consider women who search specifically for other women in the following pages, they do so out of a sense of isolation, finding themselves in filmic and writerly histories where they struggle to see even a hint of other women for all the many men.

This will most of all be an account of women looking at the world, and doing so with art, film and literature—for the world need not come at the expense of the aesthetic. One of these woman is a contemporary of Luce Irigaray, and the others are readers of her, but none shares with late Irigaray the following sentiment: ‘What nature offers us to experience is so beautiful, multiple, and speaking to all our senses that more often than not I prefer to spend a moment in it, instead of going to the cinema or an exhibition’ [

1] (p. 43). Hélène Cixous comes differently to the world, with eyes full of art (and painting in particular). No either-or economy for her separates the two. Art can indeed be an inadequate imitation of the world—and writing, for her, an even poorer one—but mediation is not fundamentally an obstacle to nature. Rather, art, reading and writing can offer a pleasurable passage to it.

As it is for the filmmaker Laida Lertxundi and the theorist Kaja Silverman, the self is also involved in looking for Cixous: to look towards the world is not to martyr or to transcend the self. Similarly, a language of desire intermingles with a language of things: erotics, with an ethical imperative to attend to nature. Turning from introspection to respond to the wider world too, each of these three women does decentre the self (a result of deconstructive beginnings or borrowings in each instance) but she does not efface it. Writing from the ‘I’ in the case of Cixous, not opting for an objective language of long-distance shots and long-enduring takes in the case of Lertxundi: subjectivity and positionality is a part of an approach to the world for these women. Neither one undergoes, in the manner of Iris Murdoch, a process of ‘unselfing’ as she observes the things of the world—a process in which the ‘brooding self is disappeared’ and there ‘is nothing now but kestrel’ [

2] (p.82). Were Cixous or Lertxundi to regard such a bird, the look would not exist in a vacuum: it is possible to look, and to look well, without negating or vanishing the self.

Were Cixous or Lertxundi to look at a bird, the chances are that they would, tirelessly, look at it again and again, each time from a different angle, with both woman and bird changed with each regard. If there is, to quote Jane Bennett, a ‘vagabond’ quality here, ‘a propensity for continuous variation’, then these mutations are not the agency of non-human materiality alone, and nor are they the activity of one human alone [

3] (p. 50). After Silverman, I argue for our collective look at the world, in which one ‘pair of eyes make good where some other pair fails’: some find beauty where others’ eyes were not able to see it, where others’ words were not able to name it [

4] (p. 26). Across repeated images of oranges in Cixous and of lemons in Lertxundi, one image-spectator or image-reader encounter is able to illuminate what is beautiful or ‘good’ in the fruit where another fails. This will be an account of women looking, then: with writing and filmmaking, again and again.

2. Thinking Women with Fruit

Fruit is visible across various instances of women’s art, film and literature. In a short story by Claire-Louise Bennett—‘Morning, Noon & Night’ (2015)—her narrator looks to a windowsill where light might fall. Here, ‘a bowl especially for fruit can be placed’ [

5] (p. 3). In the aesthete mind of this narrator, a bowl especially for fruit is full of writerly and painterly potential. Looking at fruit contains the seeds of a creative act. Put in the hands of another woman writer or filmmaker, however, fruit resonates more with feminine corporeality and sexuality than with the possibility for artistry in the everyday. Consider Lucile Hadžihalilović’s eighteen-minute film

Nectar (2014) as an example: a woman in a post-innocent garden smears half a lemon with honey, flirtatiously licks and sucks it, then passes it via a hole in a wall to a man who does the same. In

Nectar, even the sharpest, sourest fruit is plentiful in erotic potential.

Whether fruit for women is erotic, painterly or writerly, thinking women with fruit can be disturbing and vexing—especially in a contemporary feminist context. When it comes to women and nature, accusations of determinism abound [

6]

1. Some women, as we have seen and will continue to see, take fruit for the page or the screen nonetheless. In

Nectar, a piece of fruit is suggestive of a vulva; the licking and sucking, of a sexual act. In ‘Morning, Noon & Night’, meanwhile, fruit is imagined next to a window and in relation to light. Between the two, the first approach to fruit was more common of women filmmakers in the mid-twentieth century. As women ruminated on fruit to embrace or to experiment with an historical resonance between fruit and the feminine, so the flesh of one often mirrored the other; juiciness paralleled jouissance [

7]

2. Take, as an example, Agnès Varda’s

L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958). Framed across three shots to be headless, only swollen body, a pregnant woman is juxtaposed across a cut with a similarly spherical pumpkin. Through this formal arrangement, close-ups of pumpkin pulp and seeds come to rhyme with close-ups of the gravid stomach. In another short film by a woman, corporeality is connected with fruit not by way of montage but by way of suggestion. In Karen Johnson’s

Orange (1970), the titular citrus fruit is fingered, peeled and segmented, bulging across a series of extreme close-up that are set, as if with a wink, to the soundtrack of a striptease. In Barbara Hammer’s

Women I Love (1976), meanwhile, the oscillating, pulsating zoom used in shots of an artichoke and of a cauliflower is identical to the oscillating, pulsating zoom used in shots of a woman’s pubis—and citrus slices also come into the frame from time to time. As in

L’Opéra-Mouffe, echoes in the formal composition of things in

Women I Love invite comparison between those things: edible, organic matter on one hand and the female body on the other.

Hadžihalilović’s honeyed lemon accords with the eroticism of Hammer and Johnson, who link or liken either fruit or vegetables to female genitalia, indifferent to charges of essentialism. By contrast, Bennett bypasses this entirely, and she is also uninterested in implications of fertility in either fruit or vegetables (dissimilarly to the Varda of

L’Opéra-Mouffe). Neither curves to caress nor child-bearing hips are envisioned in the fruit bowl of ‘Morning, Noon & Night’—only inspiration for painting and writing. Bennett’s artful narrator states that ‘it’s no surprise at all that anyone would experience a sudden urge at any time during the day to sit down at once and attempt with a palette and brush to convey the exotic patina of such an irrepressible gathering’ as the things collected in a fruit bowl on a ‘nice cool windowsill’ [

5] (p.4). Often in a room without a nice cool windowsill during the lockdowns of 2020, I had something of the same urge while watching Chantal Akerman’s

La chambre (1972) online. As Babette Mangolte’s pivoting camera pans across a circular table on which oranges or grapefruit are arranged alongside tableware and pastries, I pressed ‘command’, ‘shift’ and ‘3′ on my keyboard to take a screenshot of the image, bathed beautifully in natural light falling through the window of the eponymous room. I looked at the image again and again.

What to make of a sudden urge of a woman to capture colours, shapes and textures of fruit as seen in the light of day, without going on to equate fruit with her own flesh and skin? What remains between fruit and the feminine then? Cixous and Lertxundi gather images of fruit over and again: apples, oranges and lemons. While Cixous and Lertxundi are well-known for seeking something of the feminine for writing and filmmaking, fruit in these texts and these films tends not to be equivalent to female anatomy, and the juiciness of fruit is not a mere shorthand for feminine jouissance. If Cixous and Lertxundi recognise an historical relation of women to nature in art, literature and philosophy—especially in images of apples—then an essentialist equation of one to the other is loosened, as the texts and the films situate apples, oranges and lemons first of all as things in the world. Cixous and Lertxundi do not eradicate the distance between the human and the non-human on the ground of some mystical feminine: fruit and women are not intrinsically entwined. Yet, women do look at fruit and with fruit.

Taken with the beauty and the light of fruit, both Cixous and Lertxundi turn not only from the female body but also from the feminine self towards the world. Crucially, as aforementioned, both turn towards the world via art, film and literature. For Cixous, reading the literature of Clarice Lispector is a path to ‘reading’ the world, and doing so with fruit. ‘Read Clarice as she reads the world to us,’ Cixous instructs us. ‘Clarice’ reads the world by ‘the light of the fruit’ [

8]. For Cixous, reading for colour, fruit and light allows us to approach difficult or oblique experimental writing, such as that of Lispector, and also allows writers to illuminate the world to us, even if in the slightest of fragments or in the darkest of rooms. Something as simple as an apple in a bowl or an orange on a table is able to flood the mind of the reader with red, with orange—thus vivifying the world of the book and bringing book closer to world.

After Cixous, I suggest that reading for colour, fruit and light also allows us to approach difficult or oblique experimental filmmaking, such as that of Lertxundi. I hope not to make too much here of a passing comment in a recent festival report—but there is something exciting about an experienced film critic confessing he does not ‘feel very much like a “film critic” while watching and writing about Lertxundi’s films’, continually finding himself reading ‘for meaningful things to say’ [

9]. If the old words and ways are ineffectual, then let us find new ones. Cixous is not often called upon to approach film (and nor indeed is fruit). Affinities that circle around femininity and fruit, however, open up a space to read her writing in conversation with Lertxundi’s films. Cixous and Lertxundi remake the relation between fruit and the feminine. For the most part, the relation of women to fruit is one in which women are no more and no less than creatively appreciative of fruit—and fruit belongs, in the beginning, not mythically to women, but instead to the world.

3. Allowing Us This and That Apple

Some of the oldest stories of beginnings bind feminine figures to fruit. Against interdictions on eating in the Garden of Eden and in the underworld, Eve bites an apple and Persephone consumes arils from a pomegranate. Cixous is taken with both of these feminine figures, these disobedient daughters flying in the face of the law with the act of eating—but not necessarily with the next part of each story, traditionally told. For Cixous, feminine appetite and curiosity, symbolised by fruit, need not lead to the fall of humanity or to absence, missing and mourning (had Persephone not eaten in the underworld, she would not be forever sentenced to spend part of every year there, taking the fructuous springtime with her when she does) [

10]

3. Cixous is interested in the innocence from which feminine appetite and curiosity arises, rather than the fateful knowledge to which it apparently leads. After her encounter in the mid- to late 1970s with the literature of Lispector, in particular, she is interested in regaining an antediluvian innocence for writing. ‘How does the poet become self-strange to the point of the absolute innocence?” she asks [

11]

4. This is not to cast the point after having eaten forbidden fruit in shame—caught in a state of regret, wishing to reverse time and the rebellious act—but to assert that some sort of innocence is still possible in the wake of eating an apple or pomegranate arils.

Lertxundi is just as sanguine about apples as Cixous is. In The Room Called Heaven (2012), a naked woman walks into the frame to lie in repose on the wooden floor of a living room. In the foreground, there is a rug as well as a mussed sheet, but she dismisses these minor comforts to recline instead in an oblong of warm sunlight on the wooden floor. In a matter-of-fact shot that is uninterrupted by, say, a seductive close-up to imply sinful eating, she holds out an apple before her and goes on to bite it, to chew it, to contemplate it some more, to take another bite and another—all of this, not unlike Akerman in La chambre, toying with an apple while lying in bed. After eating an apple in Akerman’s and Lertxundi’s films, there is no fall. In The Room Called Heaven, an ascent in fact follows the scene: skies superimposed onto an image of slatted doors that open and close, open and close. Akerman’s Eve and Lertxundi’s Eve go unpunished.

Although the appeal of Eve and Persephone to Cixous has been discussed in critical discourse on the writer, the importance of the apple to Cixous beyond the Book of Genesis is little considered. Turning to the apple in painting, Cixous recalls Eve and Persephone as she forgoes abstinence for the pleasure of eating. For all that she admires in Paul Cézanne, for instance, she feels differently about apples to him and other painters.

In what way do I feel differently to these painters I love? In my way of loving an interior apple as much as an exterior apple. […] Myself, I would have eaten it. In this way, I am different from those I would like to resemble. […] In my need to share with you the food […] the words, the painted food and also the not-painted food.

‘Myself, I would have eaten it.’ Cixous likes pleasure by way of the tongue as well as pleasure by way of the eye: one does not substitute the other. She wants an apple, an actual apple to taste and to share, the food, not-painted, ‘and also’ an image of an apple, painted or in words. She expresses a similar desire in the same essay for an experience of the sea that is simultaneously unmediated and mediated. ‘I would like to be in the sea and render it in words,’ she writes—before deeming it ‘impossible’ [

12] (p. 105). All she can do, she concludes, is tell us of the desire.

Cixous is not naïve, then: she suspects, I think, that she cannot have an apple and eat it too. Yet, she wants more than ‘an exterior apple’. She likes, in this regard, the apple as she sees it in the literature of Lispector. Referring to her debut novel

The Apple in the Dark (1956), Cixous writes that Lispector ‘calls the apple with such intelligence’ that ‘everything the apple signifies, contains for us’, is there at the same time as there is ‘in the apple the promised sustenance’. Cixous concludes, ‘And so there is

this apple’ [

13] (p. 67). Altering the definite article to a deictic and emphatic ‘

this’, she shifts from an assumption of common knowledge (‘everything’, ‘for us’) to an identification of an object that is specific, at hand. Lispector for Cixous enfleshes ‘the apple’ as symbol by pointing to ‘

this apple’ ‘in’ which there is nourishment. Cixous and Lertxundi similarly realise oranges and lemons as objects that ‘contain’, intimately, as well as ‘signify’ on the surface.

When we think of the apple, we might think of forbidden fruit—better left uneaten or untouched. For Cixous, this is no fun, not to mention unrealistic. In place of archaic prohibition or drastic damnation, she wants to permit us this apple, an apple in the world, and that apple, the one of art’s eye. When we think of apples after Cixous, we might think about eating them and also painting them. As I progress later to consider Cixous’ oranges and Lertxundi’s lemons, looking at fruit supersedes eating it. I underline a taste for fruit here not only to reframe fruit, contrary to myth, as accessible and vital, but also as a reminder that neither Cixous nor Lertxundi is ascetic in looking: looking is not a form of absolute distance and reserve. Although not sexual or visceral, looking remains connected, for both writer and filmmaker, to other kinds of feminine jouissance: at once an artful form of jouissance and that of being in the world, enjoying the gift of fruit.

4. Approaching World Spectatorship

Lertxundi’s image of opening and closing doors is an apt one for exploring Cixous’ and Silverman’s turns towards a post-deconstructive perspective in which opening and closing, presence and absence, coexist. Cixous in an anglophone sphere and Silverman in the field of film studies are most well-known as deconstructive writers of the feminine who move away from vision, for its implications of masculinity and mastery, and towards the body that is traditionally overlooked or dismissed. Cixous is famous, for instance, for her call for women to write the body and make it heard in ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’ (1975) [

14] (p. 880). Silverman is best known as the feminist theorist of

The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema (1988). Yet, both women return from bodies, sounds and voices to vision after these texts. Cixous does so sooner, after her encounter with Lispector in the mid- to late 1970s; Silverman, in

The Threshold of the Visible World (1996) and

World Spectators (2000). Where both deconstructive writers were influenced by Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis in the first instance, their turns to vision take them towards philosophy too (towards that of Martin Heidegger, for example). Ultimately, Cixous and Silverman arrive at a position of world spectatorship without forgetting the absences and withdrawals, the darkness and deferrals written throughout deconstruction—to use the image from

The Room Called Heaven again, the doors onto the world close as well as open. Cixous and Silverman nonetheless put a new emphasis on light and presence so as to attend to the world.

Across

The Threshold of the Visible World and

World Spectators, Silverman tries to wrest vision from influential theories of a narcissistic gaze in order to explore an alternative erotics and ethics of looking: perhaps it is possible, she suggests, to look with love and with care. Silverman moves on from ego, gaze and mirror reflections to cast light instead on forms of looking that are affirmative, collective and productive. In

World Spectators, she focuses after Heidegger on appearance as ‘a coming forward into view or becoming visible’ and ‘a stepping forth’ [

4] (p. 3). Referring to the image of the clearing in Heidegger, she speaks of ‘the open space’ within which things can emerge [

4] (p.30). Silverman also states that it is we who ‘bring things into the light by looking’ and we who ‘conceal them when we fail to look’ [

4] (p. 7). While Silverman, curiously, does not address film in

World Spectators, I am interested in an emphasis on looking from a woman once closely associated with feminist film theory.

Cixous writes similarly in ‘Clarice Lispector: The Approach’ (1979) of an ‘invisible aura [that] forms around beings who are looked at well’ [

13] (p. 66). Clarice—as Cixous sometimes calls Lispector, presumably for the resonance of that name with clarity and luminosity—teaches Cixous how to see what is plain to see and what calls out to be seen. ‘Clarice gives us to see,’ she states in a seminar on Lispector from the early 1980s [

15] (p. 97). ‘Clarice looks,’ she elucidates in ‘The Approach’, ‘and the world comes into presence’ [

13] (p. 61). Lispector, to recall Silverman, brings things into the light by looking. In ‘The Approach’, Cixous offers as an example a bouquet of flowers that is given to a character in one of Lispector’s short stories, ‘The Imitation of the Rose’ (1960). When not given and therefore unseen, these flowers would be ‘blurred, almost not flowers in [the] field of unvision’. Yet, because given and seen, these flowers—‘all wet with looking’—‘rose up looked-at’ and ‘shone’ so lustrously as to facilitate ‘reading by the light of flowers’ (a sentiment recalled by Cixous when she writes of reading by the light of fruit) [

13] (p. 72). For Cixous and Silverman, taking time to look, and to look well, is vital: the world is concealed, blurred, almost not world without us.

Appearance for Silverman is dependent on a meeting of absence, connected to a language of desire, and presence, connected to a language of things. When Cixous tells us of an impossible longing to be in the sea and to render it in words, she reaches towards a language of things while using a language of desire, attempting to make ‘the rose-colored beach and the pearly ocean’ present to the reader through description while underlining that these words are in fact ‘colorless’ and barely ‘sonorous’ [

12] (p. 105). She echoes a meditation on adjectives and description from

The Book of Promethea (1983) here, in which her anxious narrator worries that ‘calling a white egg white risks causing the egg to seem to disappear along with the one calling it white and the whole visible world’ [

16] (p. 183). For Silverman, the risk of such disappearance is circumvented ‘when the perceiving subject is ‘open’ to the perceptual object’:

To be ‘open’ in this way means to renounce all claim to be the master of one’s own language of desire. It means, indeed, to surrender one’s signifying repository in the world, to become the space within which the world itself speaks. To abdicate enunciatory control in this way is, however, not to lose, but to find one’s language of desire.

Silverman affirms the importance of vision, but it is not allied to a stance of transcendence. For her, world spectatorship is in part a process of abdicating, renouncing or surrendering sovereignty and accepting, without mastering, an absence in the self. Cixous’ inclusion of moments of doubt as she reaches towards the world from writing in effect creates an open space—one which is not always already known—within which things can emerge.

According to Silverman, nature addresses us formally—in colours and movements, in patterns and shapes—and asks from us ‘that very particular passion of the signifier’ [

4] (p. 144). Nature seeks from us naming and calling, our words and our images: world spectatorship is not just looking at the world, but responding to it in language. Silverman argues that ‘the human imperative is to engage in ceaseless signification’: it is in the end ‘this never-ending symbolization that the world wants from us’. And the world wants it from us, plural. Silverman asserts that it is only ‘as a collectivity [that we can] be equal to the demand not only to find beauty in all the world’s forms, but to sing forever and in a constantly new way the jubilant song of that beauty’ [

4] (p. 146). As I come across the last sections to discuss oranges in Cixous’ writing and lemons in Lertxundi’s films, I enumerate various forms of orange and various forms of lemon. Both appreciating fruit as it exists in the world—in a bowl on a table, on a branch in a tree—and also responding to it with aesthetic experimentation, Cixous and Lertxundi engage in something like the ceaseless signification and never-ending symbolisation of Silverman’s world spectator. As Cixous and Lertxundi long for something in common with other women in writing and filmmaking, furthermore, I take these repetitions of oranges and lemons as amounting to invitations to a collective look, equal to the demand to find beauty in these forms of the world.

5. The Gift of Sight: Hélène Cixous’ Oranges

‘Sometimes the repeated word becomes the dry orange-skin of itself,’ writes Lispector, ‘and no longer glows with even a sound’[

12]

5 (p. 127). Cixous reads this and rallies nonetheless for ‘the right to repeat the word until it becomes dry orange-skin, or until it becomes fragrance’ [

12] (p. 128). If the repeated word for Lispector sometimes ‘becomes a hollow and redundant thing’, then Cixous sees repetition differently. In an essay after her encounter with Lispector, and very much in the mode of a world spectator, Cixous writes the word ‘orange’ repeatedly as she recounts a sudden ability to see other women and the world beyond writing. Any resonance of fruit with something of the feminine unravels from a connection or a comparison of an orange with genitalia (as occurs in the films

Orange and

Women I Love). As we will see, Cixous reframes oranges as aesthetic material and also resituates oranges as things that exist in the light of the world: oranges are painted and also not-painted. While we are able to write with the first kind of orange, women share with the second kind a state of being in the world.

As Verena Andermatt Conley ascertains, an earlier image of the orange in Cixous’

Portrait du soleil (1974) stands as ‘a simulacrum of the sun, god, father and capital’ [

10] (p. 104). Later, however, the orange is less heliocentric and phallocentric for Cixous. After Lispector, it is instead consonant with a more diffuse, diverse light, with the gift of sight and women. In a bilingual essay entitled ‘To Live the Orange/Vivre l’orange’ (1979), Cixous reflects on writing B.C., before Clarice. She laments,

[…] my writing was grieving for being so lonely, sending sadder and sadder unaddressed letters: “I’ve wandered ten years in the desert of books—without encountering an answer”, its letters shorter and shorter “but where are the amies?” more and more forbidden “where the poetry”, “the truth”, almost unreadable, messages of fear with no subject “doubt, cold; blindness?”.

Cixous narrates an impoverished version of écriture féminine: for some time, writing the feminine was writing in doubtful, cold and blind solitude, with other women nowhere to be seen. (Note that Marguerite Duras and Colette, the two lonely examples of women who practice écriture féminine according to Cixous in ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’, are mentioned only in a footnote to the text and only briefly [

14] (p. 879). Cixous asks herself and her writing, ‘

What have you in common with women? When your hand no longer even knows anymore how to find a near and patient and realizable orange, at rest in the bowl?’ [

11] (p. 10) From here, Cixous continues to parallel that near but unseen orange with women.

Starting from a single orange, ‘a given orange’, Cixous offers her reader ‘an open, bottomless species of orange’ in the ceaseless, never-ending mode of a world spectator [

11] (p. 16 & 18). Forms of orange include variations of fruit such as ‘a blood orange’ Elsewhere, orange becomes colour and light: ‘an orange beam’ [

11] (p. 88). Cixous adds

ange, the French for ‘angel’, to the end of ‘Lispector’ to grow an orange from her name: the seraphic arrival of the woman writer is signalled in

Lispectorange [

11] (p. 113). Although a near and patient and realisable orange is in the end found, furthermore, the orange is a gift rather than a given. Access occurs but is not guaranteed: it might come and go. In an instance of unusual reserve, Cixous writes, ‘I leave the orange to herself, in her climate’ [

11] (p. 22). Here, the orange observes Persephone’s seasons: it is not forever ripe for taking, and absence is balanced with presence. I have listed only a handful of permutations here, yet over the course of ‘To Live the Orange’, the word ‘orange’ becomes an incantation of sorts, a word with which to call out to other women and the world from the desiring space of writing.

After wandering for a decade in a desert of books, Cixous writes of Lispector: ‘She put the orange back into the deserted hands of my writing, and with her orange-colored accents she rubbed the eyes of my writing which were arid and covered with white films’ [

11] (p. 14). Where the desolate eyes of Cixous’ writing are covered with white films in the English translation, ‘une taie de papier’ covers them in the French—

une taie is either a leucoma, an opaque spot in the cornea of the eye, or a pillowcase. Lertxundi’s

Footnotes to a House of Love (2007) opens as if covered with white films, on a white screen. Soon it becomes clear that the white screen is a white sheet—proximate to

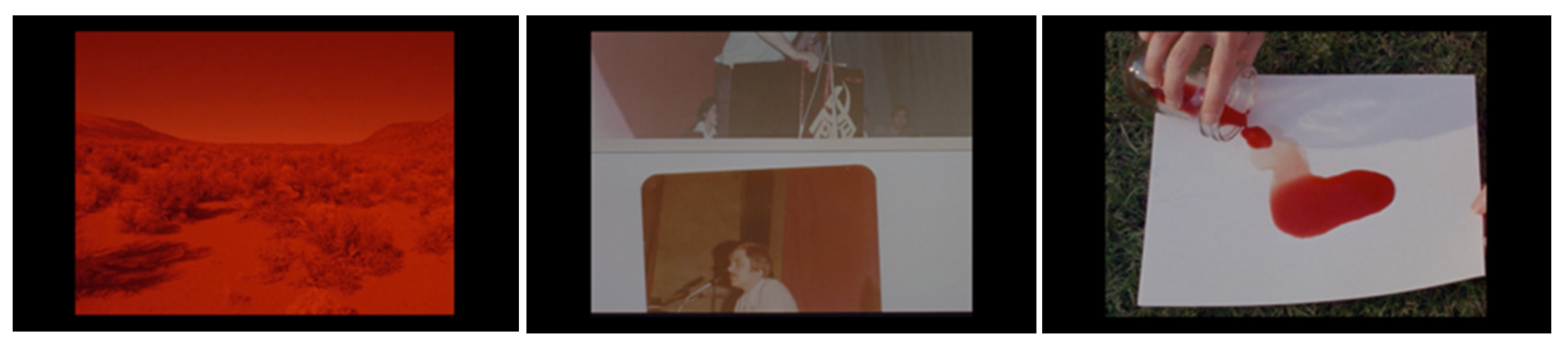

une taie, a pillowcase—and one that is held at the edges by two pairs of hands in a dry, dusty Southern Californian desert. It creases and folds. It is then suffused with some orange-coloured accents, in effect rubbing the eyes of the film that was arid and white (

Figure 1).

Cixous rejoices at Lispector’s orange-coloured accents, re-juicing her arid eyes. Lertxundi seems similarly allergic to desiccation in her work:

Here’s the making of something—that’s very dry, right? But I’m also interested in pleasure. […] Talking about process is a kind of deconstruction, and pleasure constructs, makes new worlds. I am interested in feminine jouissance.

Following the orange-coloured accents of

Footnotes to a House of Love, we glimpse little else of the orange native to Southern California. In an interview, Lertxundi acknowledges that there is an ‘idea of utopia’ ascribed to the landscape, as ‘a place with oranges growing everywhere’ [

18] (p. 39). Her new worlds are filled, however, with another citrus fruit. Her films live more in the light of the bittersweet sister of the orange: the lemon. As Cixous’ discoveries of other women are accompanied by oranges, so Lertxundi’s discoveries are accompanied by lemons.

6. Lemons According to Laida Lertxundi

Handfuls of bananas, here and there. One bunch has been placed in the foreground of a mountain in

Footnotes to a House of Love. Another, in

Utskor (2013), is placed on a nice cool windowsill in Northern Norway, beside three lemons on a table

6. Someone in

Utskor removes the bananas from the frame, but the lemons remain. Of all fruits, yellow or otherwise, Lertxundi’s filmography is replete with so many lemons. After

Utskor, there is for instance a lemon in a tree—left to itself—in

025 Sunset Red (2016) and there is more than one lemon in the hands of

Words, Planets (2018). Yet, to speak of lemons in Lertxundi’s films is not only to speak of lemons with peel, pith and pips, with citric juice that drips, but also to speak to the colour of lemon and the light of lemon. Lertxundi gives us ‘

this’ lemon, an actual lemon, as well as variations on that lemon. Sometimes pale, other times vibrant, lemon is visible in other flowering and fruitful forms, in material worn and torn, and in the lettering of titles, subtitles and intertitles. What to make of so much lemon? Lertxundi’s husband, who often appears in her films, has suggested that there is ‘a sort of riddle with the lemons’ [

17]. When I had an occasion to ask whether the lemons scattered across her films bore a meaning or a metaphor, however, she smiled, ‘No, the lemons are not symbolic’. If we are to take her at her word (not believing her to be a sphinx), then we will not take the lemons as signs. Although the lemons are not signs, Lertxundi engages in ceaseless signification with lemons. In other words, the lemons are not representative of something else—a lemon for a vulva, as in

Nectar—but lemons are a part of this artist’s palette. Lertxundi films with lemons. Adopting and adapting Cixous’ advice to read Lispector as she reads the world to us, by the light of fruit, we might read Lertxundi as she reads the world to us: by the light of lemons.

In an interview from 2012, Lertxundi makes explicit mention of Cixous while discussing previous participation in a reading group focused on writing the feminine. ‘I reread and found texts that spoke to me,’ she says, going on to list Cixous, Irigaray and Julia Kristeva as writers who ‘propose the idea of creating a feminine form through writing’. With reference to these three women, Lertxundi says she is ‘interested in [the] possibility of a feminine space’ for film [

18] (p. 40). Then, in an essay from 2019 entitled ‘Form and Feeling’, Lertxundi wonders whether feminine formalism in film is possible without the influence or the knowledge of other women filmmakers who might be aligned with such a practice. Lertxundi asks herself whether she momentarily assumes a masculine subjectivity when her camera approaches a hand as she thinks of minimalism in the manner of Robert Bresson or when her camera approaches a space and she thinks of structuralism in the style of Michael Snow [

19] (p. 2). Reading Carolee Schneemann’s ‘Interior Scroll’ text from the mid-1970s, which voices a riposte to structuralist filmmaking from a feminist standpoint, Lertxundi is concerned that ‘structuralism and a feminist praxis seem irreconcilable’ [

19] (p. 3). I do not intend here to resolve an ostensible paradox of feminine or feminist structuralism; all of this is rather to underline that Lertxundi shares with Cixous a wish to correspond with other women while attempting to create a feminine space for film.

While we are in the realm of film structuralism, however, we might attend to a work with special relevance for speaking about lemons. Hollis Frampton’s

Lemon (1969) is sometimes shown together with Lertxundi’s work [

20]. In the film, the eponymous citrus fruit is plucked from the earth and set against a black background, illuminated by an orbiting light. With its thick, cratered skin, it seems—even though it is static and the substitute sun here is mobile—as if it traverses a lunar cycle: new, crescent, gibbous, full. ‘When life gives you lemons, make lemonade,’ goes the proverbial phrase. Frampton’s film more or less alters the phrase to be: ‘When life gives you lemons, make a celestial body.’ Lertxundi’s lemons are not, by contrast, transformed into satellites. One essay on Lertxundi’s work uses Eileen Myles’ poem ‘Movie’ (2007) as an epigraph; in it, we read, ‘you’re like/a moon I want/to hold/I said lemon’ [

21]

7 (p. 8). In accordance with Myles’ ‘Movie’, Lertxundi wants to hold the lemon that, in Frampton’s film, is transformed into distant moon. She wants an actual lemon as much as an aestheticised one. She wants

this lemon. In line with Cixous’ desire for the painted and the not-painted fruit, Lertxundi adds the living world to artful abstraction and allusion.

Before we come to lemons both living and artful, it is worth noting that red is prominent in Lertxundi’s films as the colour of the self.

025 Sunset Red is, she says, ‘an abstract autobiography’ [

22]. Should we seek to link Lertxundi to a community of other women, then connecting red to autobiography is reminiscent of Anne Carson’s

Autobiography of Red (1998) and Maggie Nelson’s

The Red Parts: Autobiography of a Trial (2007). Carson’s red is volcanic, Nelson’s red is violent—and Lertxundi’s red is different still. Starting with the title: 025 Sunset Red is the name of the filter used intermittently in the film. It is also a nod to Lertxundi’s ‘red’ communist upbringing. In an image of a hand pouring blood from a jam-jar onto a white page, red is also fruitful and menstrual (

Figure 2).

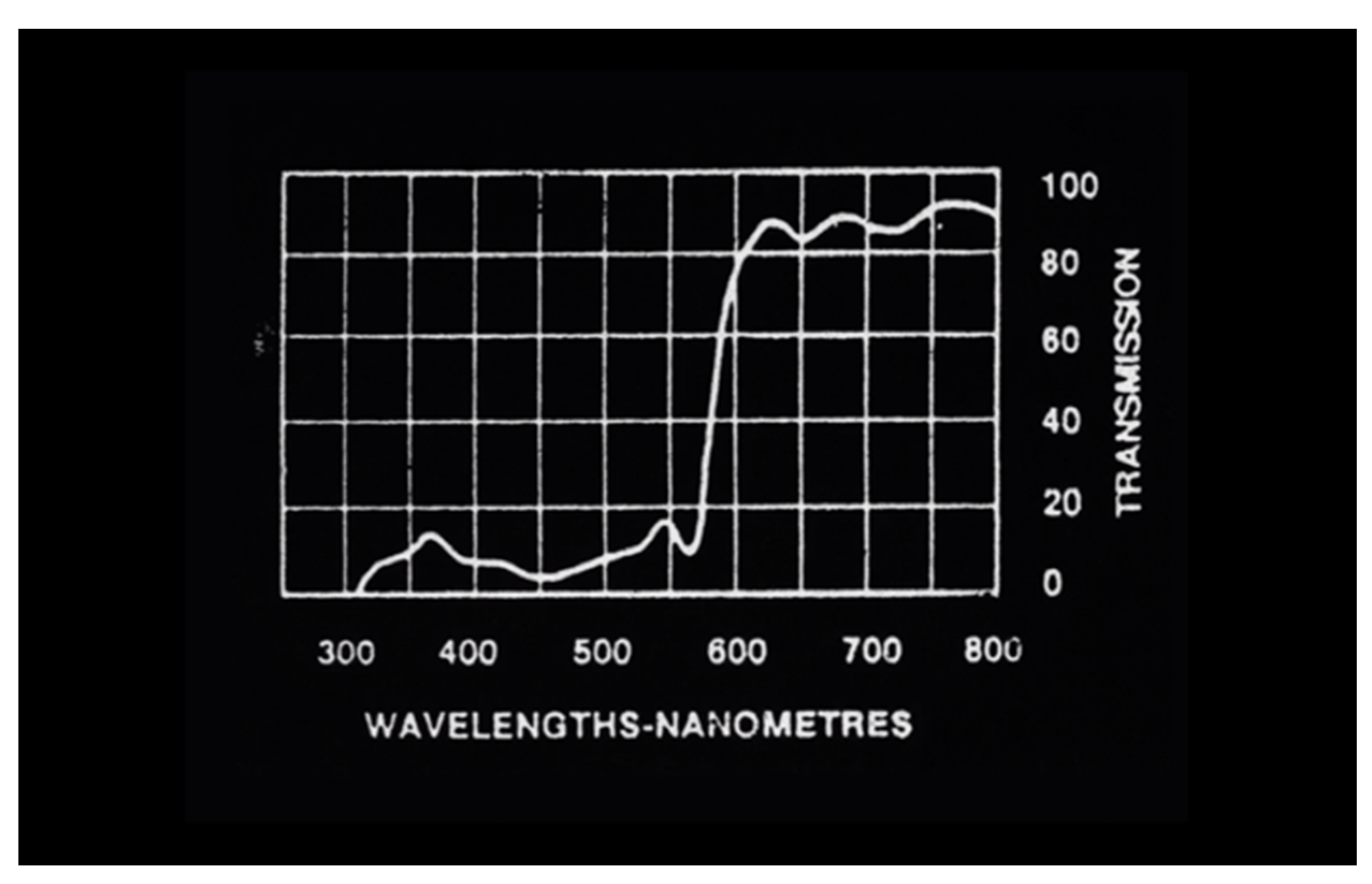

Yet, Lertxundi’s abstract autobiography indicates, in a spectrographic graph measuring electromagnetic radiation at the start of the film, an importance to yellow too. (

Figure 3.) From 300 to 380 nanometres, wavelengths are invisible, ultraviolet. From 380 to 450 nanometres, wavelengths are visible as violet. From 450 to 500, blue. From 500 to 565, green. From 565 to 590, yellow; 590 to 625, orange; 625 to 740, red. From 740 to 800 nanometres, wavelengths are again invisible, albeit felt as infrared. Where wavelengths are visible as yellow, the line on the chart leaps from a transmission rate of approximately 10 to one of approximately 60, then continues to oscillate at a transmission rate of 60 to 90 through a sunset spectrum of orange, red and infrared. If we take red to be the colour of introspection and yellow to be the colour that illuminates the world, both transmit at a high rate here. In the mode of a world spectator, Lertxundi does not efface the self as she looks at the things of the world.

Nor does she erase the body. From

Footnotes to a House of Love to

The Room Called Heaven to

025 Sunset Red, people often rest naked and horizontal in Lertxundi’s films. When there is a mountain in the frame, it is not to be conquered: in the mode of a world spectator, people surrender sovereignty in relation to the landscape. This is not however to lose a language of desire. In

025 Sunset Red, Lertxundi kisses her husband in an image saturated in amorous red. Though Lertxundi also lies naked and prone on the floor of a warehouse in the film, she is nowhere near as explicit as Hammer in her films. Unlike Hadžihalilović and Hammer, Lertxundi never mixes fruit into these lightly corporeal, gently erotic images When Lertxundi starts from

Words, Planets onwards to address motherhood, she does not give a gourd as a visual simile for pregnancy as did Varda. In

The Room Called Heaven, a hand holds a lemon in the foreground of the image, obscuring the face of a woman in the background, as if to ask, ‘What if a woman were a lemon?’ Yet, the gesture is so blunt as to be comical, and so far from the realm of the sexual, that the image is set apart from the feminine fruits of Hadžihalilović, Hammer, Johnson and Varda. In Lertxundi’s films, the feminine imaginary is not hungry for fruit as a way to represent bodies [

23]

8. Lemons coexist with bodies under the Southern Californian sun, then, but do not blend with bodies by way of montage or any other method of suggestion.

If lemons do not become a metaphor or a synecdoche for women (do not become, that is, a stand-in for them or a part of them), then women are nonetheless surrounded by colours, fruits, and the light of lemons in Lertxundi’s films. Connected yet distinct, lemons and women coexist. In

My Tears Are Dry (2009), a woman’s arm rests on a pillowcase that is the colour of etiolated lemon. In

The Room Called Heaven, a woman wears a raincoat—and the colour is lemon (

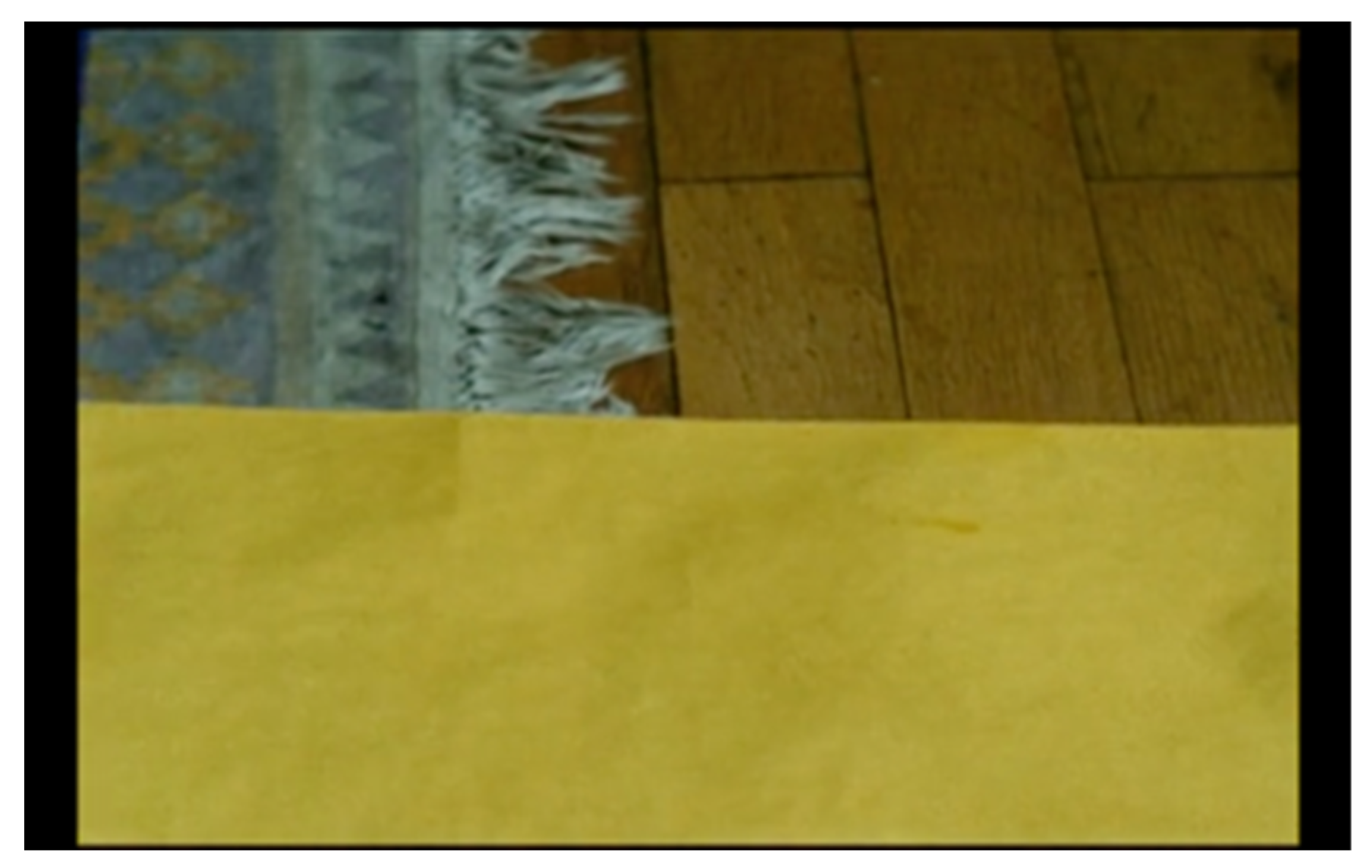

Figure 4). Some of the lemon colours across Lertxundi’s films are no more than minor details or coincidences; other interventions of lemon, however, are more deliberate, with commonalities that are difficult to ignore. On the wooden floor of

The Room Called Heaven, a sheet of lemony paper is unfurled, complementing lemon-coloured accents in the rug that remains half-visible beneath it (

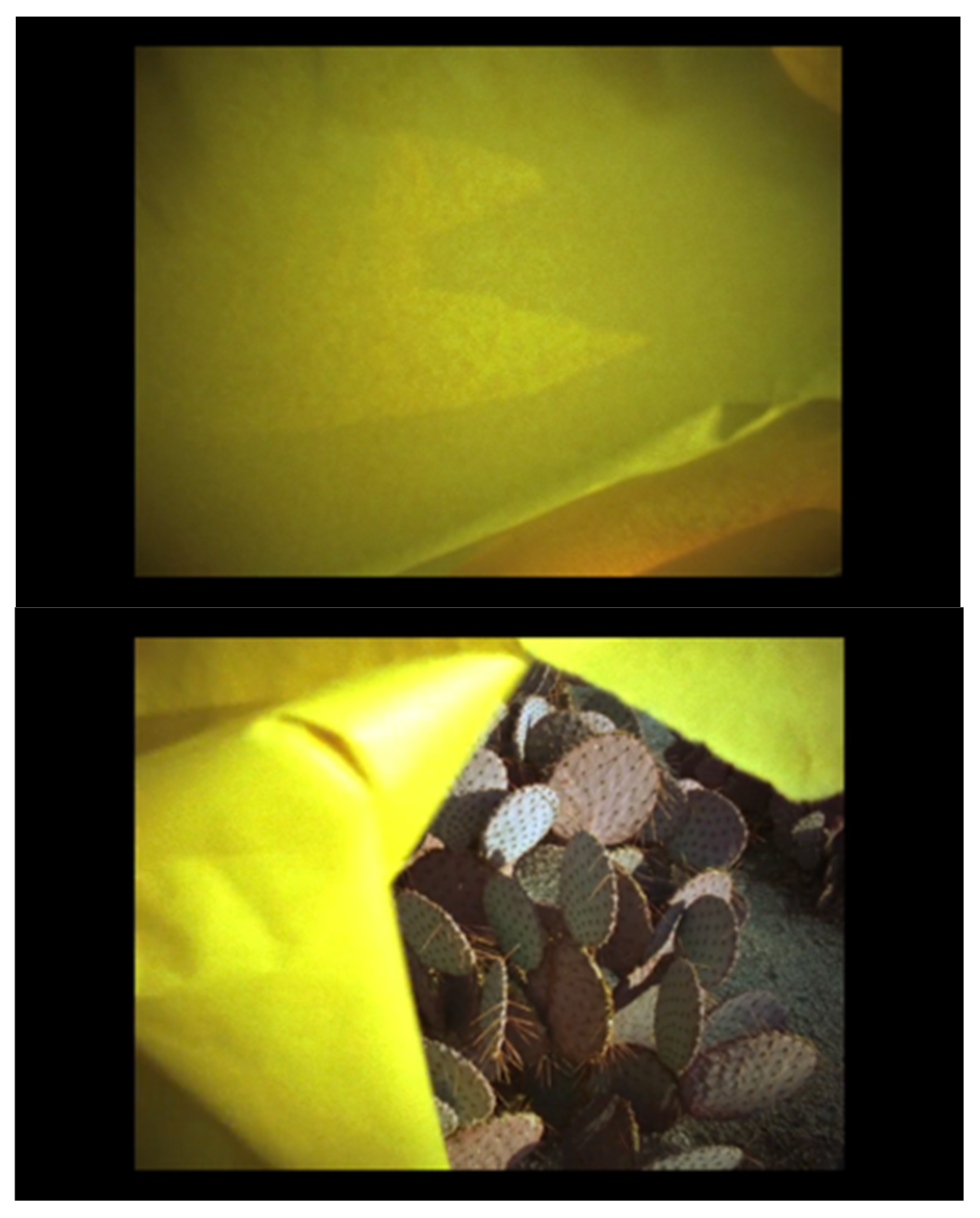

Figure 5). In

Live to Live (2015), a similar sheet of lemony paper is torn to unveil prickly plants behind it (

Figure 6). In

Words, Planets, we will see a series of similar cacti—some with lemon-coloured flowers. After the spectrographic graph in

025 Sunset Red suggests there is an increase, an importance to yellow, lemons proliferate across

Words, Planets and crop up again in

Autofiction (2020). Where red was the colour of autobiography in

025 Sunset Red, it subsides in

Words, Planets to make space for lemon, the colour that draws Lertxundi further towards other women and the world.

Against a landscape with a canopy of clouds and a faint rainbow, a hand in the foreground of the frame holds something that looks like little lemons stuffed inside a larger one. In the same setting later on, a hand holds something that looks like a lemon wishing it were instead a banana (

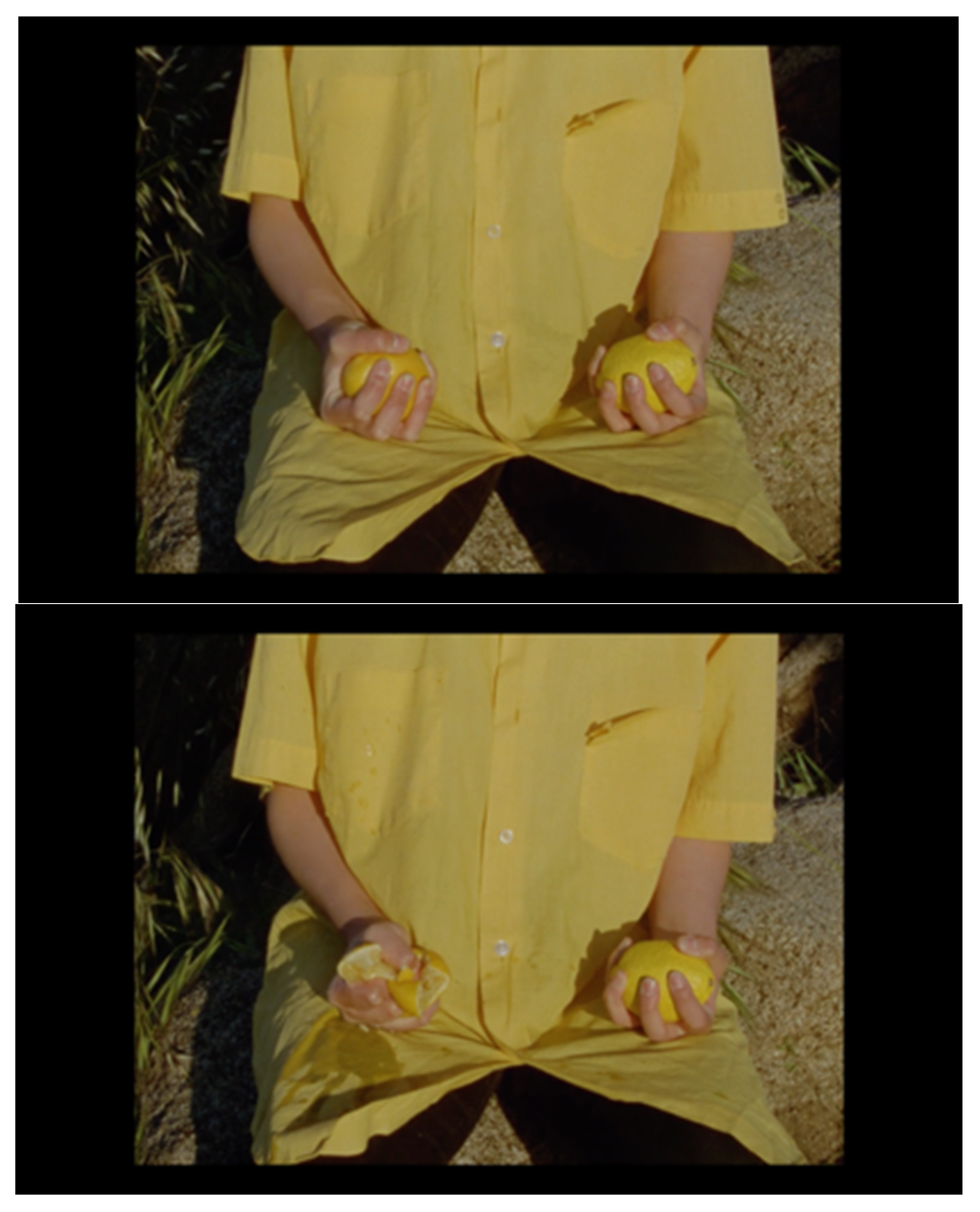

Figure 7). If lemons figure as things seen in the world, then lemon is repeatedly used as a way in which to talk about the world too. Lertxundi sees lemons and responds in lemons: in, for instance, lemon-coloured subtitles. Writing and reading, a woman wears a lemon-coloured shirt. Wearing the same shirt later on, she squeezes two lemons or objects resembling lemons (

Figure 8). One is real, the other is fake: the real one bursts and the fake one remains intact. Between lemons fake, real and rare (the banana-like lemon and the involuted-looking lemon are examples of an unusual citrus fruit called a Buddha’s hand), Lertxundi collects images of lemons in such a way that spectators may find beauty in many of the world’s lemony forms. In a post-deconstructive meeting of absence and presence, some of these lemon-filled scenes that see lemons in the light of the world later withdraw from that light. Projected into a darkened room, a frame nested in a frame, these scenes from before become lemons in the dark, lemons of their own reflexive light (

Figure 9). As much as lemons are pleasurably of the world, lemons are deconstructively of an abstracted cinematic space too: again, the world need not come at the expense of the aesthetic.

At no point is any lemon a sour-sweet symbol for the body, incorporated into it; we might wear or luminously be layered, immersed in lemon, but no methods of montage or suggestion take the flesh of one for the other. If lemon is the colour of jouissance, then that jouissance is consonant with artistic experiment (subtitles, sheets of paper, projections) or otherwise with living among the things of the world (cacti, flowers, lemons).

Inspired by Rachel Cusk’s

Outline trilogy (2014–2018),

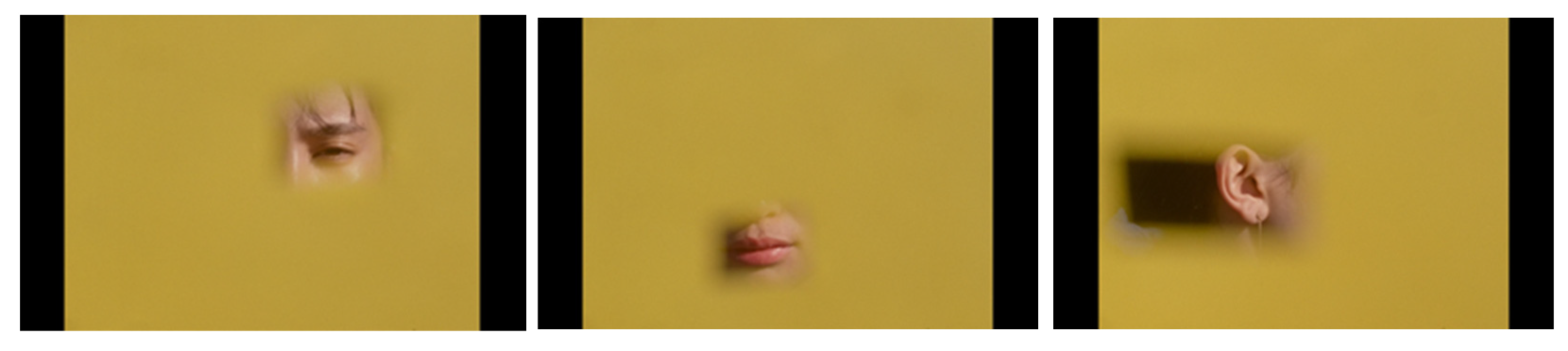

Autofiction is a conscious turn towards correspondence with other women. In a studio with rolls of coloured paper stood against the walls, women share stories related to their gender in a small group. One of these rolls is later held in front of the lens of the camera: a hole is cut into the sheet to frame the mouth of a woman, the ear of a woman, the eye of a woman. Looking, listening and speaking is therefore mediated by this sheet—and its colour, of course, is lemon (

Figure 10). Where a lemon sheet previously underlined the domestic world and revealed the natural world in

The Room Called Heaven and

Live to Live, a lemon sheet focuses attention on women’s stories in

Autofiction, just as orange is attendant to Cixous’ renewed attention towards women writers in ‘To Live the Orange’.

Anne Carson writes that a quotation is ‘a cut, a section, a slice of someone else’s orange’: ‘suck the slice, toss the rind, skate away’ [

24] (p. 75). Taking fruit as a crude image for the female body time and again, without much difference between one image and another, might desiccate and do away with fruit similarly. Cixous and Lertxundi take a cut of the world’s oranges and lemons, and linger with whatever dry orange-skin or lemon-skin that remains. Cixous repeats the word ‘orange’ and tries to rehydrate it, to revivify it, in the way of a world spectator: not taking to ice to skate away, she keeps the world’s oranges wet with looking. Lertxundi also shows us lemons as fruit belonging to the world and, like Cixous, recreates lemons in other colourful and luminous forms. In

Autofiction, she uses these forms—grown over almost a decade, from a pillowcase the colour of pale lemon—to create a new world that highlights a correspondence between women. Just as the colour and the light, the fruit and the writing of orange accompanied Cixous’ wandering out of a desert of books in which she saw no women, so lemon in these multifarious forms accompanies Lertxundi’s search for kindred women filmmakers. Rather than using associative montage or suggestion to link women, fruit and art, Lertxundi’s films function as containers in which she gathers things, things that together create a new world.

Cixous tells us Lispector looks by the light of fruit. ‘Hers, apple. Mine, orange.’ Cixous continues to ask, ‘And yours? Which colour?’ [

8]. Lertxundi’s, lemon. This is, for her, the colour of the aura that surrounds beings who are looked at well. Between fruit and the feminine, the gift of this look is what now remains.