Permacinema

Abstract

It is only in plants by virtue of the sun’s energy caught up by the green leaves and operating in the sap, that inert matter can find its way upward against the law of gravity.Simone Weil, “Human Personality” ([1] p. 81)

1. Introduction

2. The Gleaning Eye

interweaves the experiential and alimentary dimensions of gleaning in an aesthetic medium especially propitious to what the filmmaker herself designates as the gleaning of images…. the beings (both human and nonhuman) are let be without being framed in a formal narrative, while Varda exposes herself (for example, her aging hands and hair) before the lens of the camera, refusing to make sense of the images she had gleaned.([28] p.35)

more often than not, have no other choice but to procure food by seeking what remains after the harvest or in the aftermath of wasteful consumption in urban centres. Not so with the aesthetic gleaners, such as Varda herself, who engage in this activity not out of necessity but out of the freedom afforded by art. This divide is telling and troublesome to the nth degree.([28] p.35)

3. The Good Enough (Mother) Earth

The world is not enough.But it is such a perfect place to start, my love.And if you’re strong enough.Together we can take the world apart, my love.(“The World is Not Enough,” Garbage)

A gift comes to you through no action of your own, free, having moved toward you without your beckoning. It is not a reward; you cannot earn it, or call it to you, or even deserve it. And yet it appears. Your only role is to be open-eyed and present. Gifts exist in a realm of humility and mystery—as with random acts of kindness, we do not know their source.([3] pp. 23–24)

4. Permacinema in Action

Instead of a dualistic point of view of animator animating “the dead,” the human, the objects, the technical apparatuses, all become important in the process of an entangled and inseparable phenomenon—creating the animation.Alisi Telengut [31]

(t)he meaning of this agreement was the idea that Creation is here for the benefit of all humankind, and there should be no war, conflict, or fear of being able to enjoy the gifts of the Creator. That if we consider the dish being Creation, we must share and take care of all the benefits of Creation for all the generations to come.([32] p. 90)

(o)f particular importance in this age of environmental degradation is the fact that the dish with one spoon is also a covenant with nature. “Nature says, ‘Here’s the great dish and inside the dish are all the plants, the animals, the birds, the fish, the bushes, the trees, everything you need to be healthy and therefore, happy. . . .’” “The three basic rules are: only take what you need, second, you always leave something in the dish for everybody else, including the dish, and third, you keep the dish clean . . . that was the treaty between us and nature, and then the treaty between us and everybody else.([32] p. 91)

learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing, and to using both these eyes together, for the benefit of all.([36] p. 335; emphasis in the original)

an “a-colonial” approach to building cross-cultural relations based on odeimin teachings. Odeimin means “heartberry”—or “strawberry”—and it grows and thrives by sending out runners, thereby creating a networked lattice of relations between individual plants. These plants are a metaphor for individuals and communities—one cannot survive disconnected from relations with each other.… The odeimin contains within it the idea of nourishment as physically and spiritually essential to the body, incorporating an understanding of connected communities as part of the self.([13] p. 49; emphasis in the original)

(o)ne of the common threads, I think, was that connection to land, for all of us. That deep connection that we all have to land.… In Octavia’s book, she always talked about creating a whole new religion that looked to the stars, took us outside what was. But for me, for my cosmology, from my point of view, everything is right here.[37]

humans are considered deeply imbricated with the soil, water, and the environment. Animism is in fact a relational ontology [instructing us] to act respectfully to non-human others and the more-than-human world, rejecting the dualistic and anthropocentric perspectives of modernity.[31]

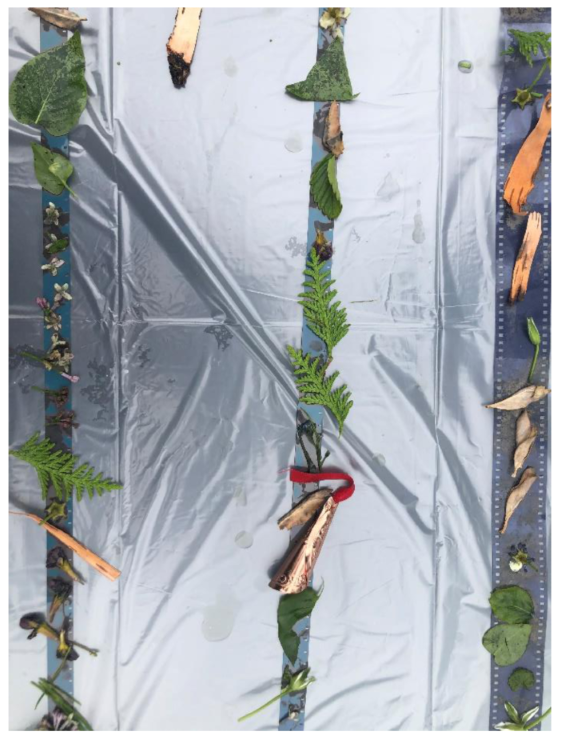

The communities’ stories and relationalities are weaved and crafted into the fabrics and materials with unique patterns, designs and techniques. In this sense, I see under-camera animation as a similar process that not only reveals aspects of materiality and tangibility, but also indicates the animation process as a phenomenon where humans, non-humans and the technical other are entangled in the co-creation.[31]

it is my attempt to develop a form of perception or sensitivity to expand my own as well as the viewer’s bond with nature.… This gesture allows the animation process and my body to be in a co-creating and even a symbiotic relationship with the plants, stones and particles. They become active agents and voices in the creation process which deconstruct the human-centred perspective.[31]

a seasonal migratory way of living by following one’s food source. This lifeway was practised for thousands of years by indigenous Americans in the Great Basin…. It was a lifeway that worked with the seasons, leaving plenty of the Earth’s resources untouched for future generations…. As they travelled the hoop, they deliberately put the seeds of the plants that they harvested back into the ground in order to keep the cycle intact.(71) [46]

5. Postscript. Cinema in Perpetuity?

A narrow Fellow in the GrassOccasionally rides—You may have met Him—did you notHis notice sudden is—The Grass divides as with a Comb—A spotted shaft is seen—And then it closes at your feetAnd opens further on—(Emily Dickinson)[48]

I think first of a meeting space where there is a collective experience that effects each individual differently but maintains a common thread that reaches us all… That said, if cinema needs to be sacrificed in order for there to be a “two hundred years from now,” I am okay with that too. I think if we can collectively watch the sun rise and fall and learn to appreciate that more, then a direct relationship with the world might be a better way to go.[50]

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | On the animal turn in film see Jonathan Burt’s Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002), Akira Mizuta Lippit’s Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), Nicole Shukin’s Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010) [17], Anat Pick’s Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), and Laura McMahon’s Animal Worlds: Film, Philosophy and Time (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2019). Shukin’s discussion is particularly relevant in the present context since she views cinema as implicated in the violent “rendering” of nonhuman life. On the vegetal turn in film see for example Chris Dymond, “New Growth: To Film Like a Plant,” Ecocene 2.1 (2021), pp. 32–50 [38], and Terea Castro, Perig Pitrou, and Marie Rebecchi’s Puissance du végétal et cinéma animiste: La vitalité révélée par la technique. Paris: Presses du reel, 2020. |

| 2. | On the return to realism, see Herve Joubert-Laurencin and Dudley Andrew’s seminal edited volume Opening Bazin: Postwar Film Theory and Its Afterlife (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), Richard Allen, “‘There Is Not One Realism, But Several Realisms’: A Review of Opening Bazin,” October 148 (2014), pp. 63–78, and Lourdes Esqueda Verano, “There is No Such Thing as One Realism: Systematising André Bazin’s Film Theory,” New Review of Film and Television Studies, 20.3 (2022), pp. 401–423. On the link between Bazin and animals see Jennifer Fay’s “Seeing/Loving Animals: André Bazin’s Posthumanism,” The Journal of Visual Culture 7.1 (2008), pp. 41–64. See also Fay’s Inhospitable World: Cinema in the time of the Anthropocene. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018, on the interlacing of cinema and the Anthropocene. |

| 3. | In De Anima, Aristotle distinguished between the different faculties of soul in plants and animals. He says: “The faculties we spoke of were the nutritive, perceptive, desiderative, locomotive and intellective, plants having only the nutritive, other living things [414b] both this and the perceptive.” Plants lack perception (that all animals enjoy), and reason (which only human animals enjoy). Aristotle, De Anima (On the Soul). Hugh Lawson-Tancred, trans. London: Penguin, 1986. |

| 4. | In response to Marder, one could point out that not only plants photosynthesise, nor were they the first to do so. It is generally believed that the chloroplasts in contemporary plants derive from an event of ancient endosymbiosis, when a free-living cyanobacterium was engulfed by another organism. See, for example John A. Raven and John F. Allen, “Genomics and chloroplast evolution: what did cyanobacteria do for plants?” Genome Biology 4.3 (2003), article 209. https://genomebiology.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-209.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2022). |

| 5. | The OECD’s own report, Beyond Growth: Towards A New Economic Approach, acknowledges that while “[e]conomic growth continues to generate the benefits of higher national income… the dominant patterns of growth in OECD countries over recent decades have also generated significant harms” (12 September, 2019, https://www.oecd.org/naec/averting-systemic-collapse/SG-NAEC(2019)3_Beyond%20Growth.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2022). |

| 6. | Degrowth remains hotly debated. For the case for degrowth, see Giorgos Kallis, Degrowth. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018, and Drew Pendergrass and Troy Vettese’s Half-Earth Socialism: A Plan to Save the Future from Extinction, Climate Change and Pandemics. London: Verso, 2022. For a critique of degrowth see for example, Leigh Phillips, “The Degrowth Delusion,” Open Democracy 30 August, 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/degrowth-delusion/ (accessed on 29 August 2022). |

| 7. | Watson’s article originally appeared in Permaculture Design Magazine (formerly Permaculture Activist) 98, Winter 2015. |

| 8. | The Odeimin Runners Club collective prefers the term “a-colonial” to indicate a resistance to “oppressive capitalist systems while taking a different path: one outside of colonialism’s hegemonic frameworks” (Schlums, et al. 49). [13] |

| 9. | Knowles describes Film Farm as a “utopic endeavour” (144), at once inside and outside the world. This is significant when considering Film Farm as a site of resistance. Knowles is open and honest about her own experience at Film Farm: “[w]e were about to close ourselves off from one kind of world, where the contentious politics of Trump and Brexit (still too fresh in my mind) were raging, in order to immerse our bodies and minds in a kind of physically engaged art-making that might be considered by some as escapist, frivolous even. I grappled with these thoughts throughout the journey, trying to make sense of the relationship between art and politics” (150). [11] |

| 10. | The 2019 programme of Saugeen Takes on Film was screened at the Fabulous Festival of Fringe Film (18-27 July, 2019), a long-running festival of experimental film that brought together Philip Hoffman, Debbie Ebanks Schlums, and Adrian Kahgee. The programme included Natalka Pucan’s The Ancestors’ Gift (2019), Sharon Isaac and Kelsey Diamond’s Thunder Rolling Home (2019), and Tiffany Kewageshig and Cassidey Ritchie’s Tune In (2019). The 2018 festival programme featured Pulcan’s Mii Yaawag (2018), Emily Kewageshig and Taylor Cameron, Zgaabiignigan (2018), and Jennifer Kewageshig ‘s How Far We’ve Come (2018). For information on the 2018 and 2019 STOF workshops at Film Farm, see https://philiphoffman.ca/process-cinema/ (accessed on 29 August 2022). See also the Archive/Counter-Archive open house event, during which the STOF films were enjoyed alongside wild edibles and traditional food, https://counterarchive.ca/saugeen-takes-film-open-house (accessed on 29 August 2022). |

| 11. | The use of plants in film processing is an established practice. Our selection of case studies demonstrates the correspondence between plant processing and Indigenous studies. Other recent examples of plant processing of film include Jacquelyn Mills’ documentary Geographies of Solitude (2022), Karel Doing’s feature In Vivo (2021), and Dagie Brundert’s short i am a (2022). The Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative (AFCOOP), for instance, runs eco-processing workshops, https://afcoop.ca/2017/09/eco-processing-film/ (accessed on 29 August 2022). |

| 12. | In the chapter titled “Energy,” Bozak describes a truly carbon-neutral cinema as “a cinema that does not leave a residue; a cinema, therefore, without a permanent infrastructure or, perhaps, any physicality at all” (17). Our conclusion suggests that such a cinema already exists. [14] |

| 13. | Varda explored similar themes far more bleakly in Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond, 1985). The film takes place in rural France and follows the life of its itinerant character Mona (played by Sandrine Bonnaire), whose death opens the film. Mona exists on the margins of society, without shelter or law, a complete outsider. In the later film, Varda returns to the question of the law, which gleaning as a liminal practice continuously challenges. For a reading of both films, see for example Allan Stoekl, “Agnès Varda and the Limits of Gleaning,” World Picture Journal 5 (Spring 2011), http://www.worldpicturejournal.com/WP_5/PDFs/Stoekl.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2022). |

| 14. | The potato (Solanum tuberosum) was cultivated in the Andes and transported to Europe by colonists around 1562, thirty years after Francisco Pizarro reportedly encountered potatoes in Peru. See J.G. Hawkes and J. Francisco-Ortega, “The Early History of the Potato in Europe,” Euphytica: International Journal of Plant Breeding 70 (1993), pp. 1–7. |

| 15. | At the opening of her art exhibition Patatutopia at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003, Varda appeared dressed in a potato suit. |

| 16. | By some delightful coincidence, the film’s theme song was performed by the band Garbage. Indeed, the by-products of a never-enough psychology and economics of growth are surplus and waste. The proposed solutions of the “green economy” (Kothari et al., 2014) and “green capitalism” (Buller 2022) have so far failed to tackle the world’s ever-increasing tonnages of trash. See Ashish Kothari, Federico Demaria and Alberto Acosta, “Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy,” Development 57.3–4 (2015), pp. 362–375, and Adrienne Buller, The Value of a Whale: On the Illusions of Green Capitalism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022. |

| 17. | On plants’ indifference to power-possessing and enhancing modes of being see Michael Marder’s “Resist like a plant! On the Vegetal Life of Political Movements,” Peace Studies Journal 5.1 (2012), pp. 24–32. |

| 18. | Weil was interested in modes of reflective detachment, what she called “attention,” that have existed for centuries across east and west. They include Meister Eckhart’s idea of “gelassenheit” (letting be), and the Indian “aparigraha” (the virtue of non-possessing or non-grasping in Jainism). |

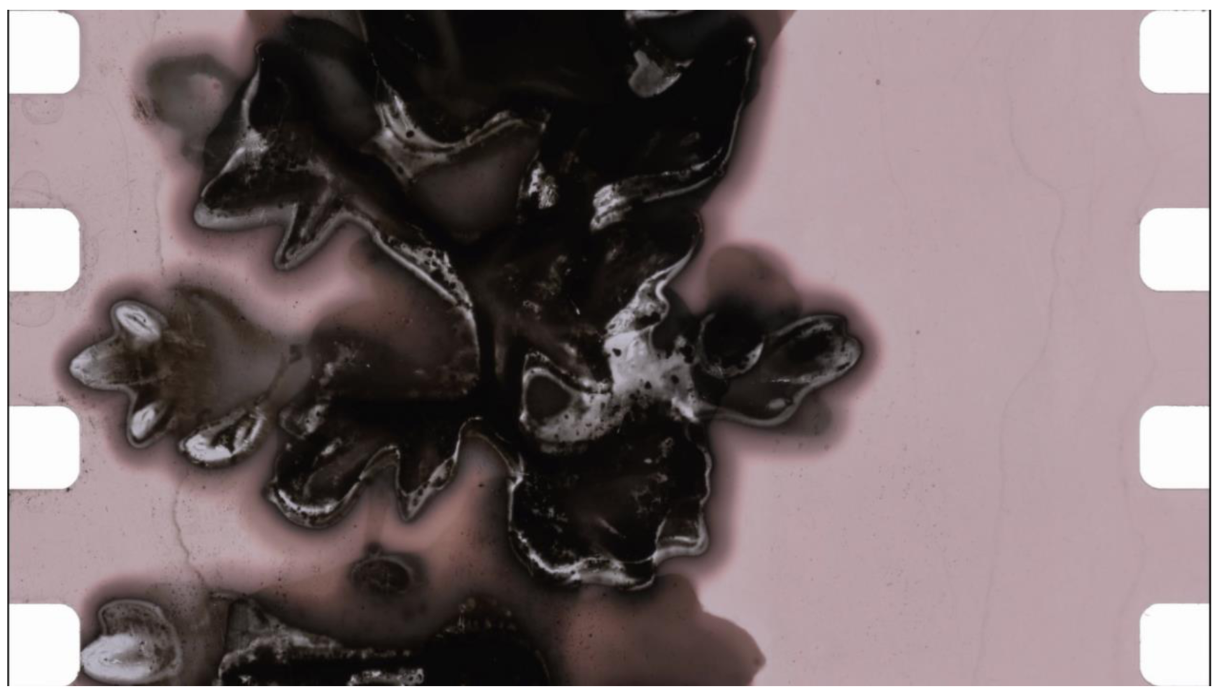

| 19. | Hoffman introduced us to thinking about the synchronicity of plants and films’ gestation periods, when processed with flowers. In our interview, he said: “My statement ‘the film will bloom when it is ready’ relates to the gestation time of an artwork, when the unconscious is aligned with the creative process, and a work is ready to be born” (Hoffman 2022). [35] |

| 20. | See Karel Doing’s blog on phytography, https://phytogram.blog/ (accessed on 29 August 2022). See also Doing’s 2020 article, “Phytograms: Rebuilding Human-Plant Affiliations.” [42] |

| 21. | The impact of plant juices on photographic emulsion was verified in William Henry Fox Talbot’s early photograms, although he ignored plants’ agency. On this, see: Dymond (2022) “How to Look at Plants?” [21] |

| 22. | In their article, the Odeimin Runners Club resist conflating their relational approach with Bruno Latour’s Actor Network Theory (ANT): “odeimin teachings extend beyond ANT by acknowledging spiritual and cultural forms of knowing and relating beyond that which can be explained by senses and deductive reasoning alone” (Schlums et al., 54). [13] |

| 23. | Many of Telengut’s artworks can be seen on her website: http://alisitelengut.com/ (accessed on 29 August 2022), which also includes links to many interviews. In May 2021, Telengut conducted a particularly informative interview with Haliç University, available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ep8AW8IhNjE (accessed on 29 August 2022). |

| 24. | Biosemiotics, the pre-linguistic biological production and reception of meaningful signs, operates in two dimensions: movement and time. As Eduardo Kohn explains, “all life is semiotic and all semiosis is alive.… the locus… of a living dynamic by which signs come to represent the world around them to a ‘someone’ who emerges as such a result of this process. The world is thus ‘animate.’ ‘We’ are not the only kind of we.” (16) Biosemiosis is the primary meridian through which “multispecies relations are possible . . . and also analytically comprehensible” (9). We verify others’ possession of a unique lifeworld and an internal point of view by their ability to relay meaning by moving in time. Kohn’s conception of life is strikingly cinematic. Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2013, p. 16. |

| 25. | The end of cinema has been repeatedly proclaimed. See for example, André Gaudreault and Philippe Marion, The End of Cinema? A Medium in Crisis in the Digital Age. Timothy Barnard, trans. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015, or Paolo Cherchi Usai, The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age. London: BFI, 2019. |

References

- Weil, S. Human Personality. In Simone Weil: An Anthology; Miles, S., Ed.; Penguin: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marder, M. For a Phytocentrism to Come. Environ. Philos. 2014, 11, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmerer, R.W. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mollison, B. Introduction to Permaculture; Tagari Publications: Sisters Creek, TAS, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy, T. The Politics of Permaculture; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J.; Decolonizing Permaculture. Midcoast Permaculture. 19 January 2016. Available online: http://midcoastpermaculture.com/decolonizing-permaculture/. (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Spangler, K.; McCann, R.B.; Ferguson, R.S. (Re-)Defining Permaculture: Perspectives of Permaculture Teachers and Practitioners across the United States. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, K.; Leger, F.; Ferguson, R.S. Permaculture. In Encyclopedia of Ecology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2019; Volume 4, pp. 559–567. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01742154/document (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Salmón, E. Iwígara: American Indian Ethnobotanical Traditions and Science; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependece; Clear Light: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, K. Experimental Film and Photochemical Practices; Palgrave: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, P. Our Mandate. Available online: https://philiphoffman.ca/film-farm/our-mandate/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Schlums, D.E.; Kahgee, A.; Tabobondung, R. Indigenous and Migrant Embodied Cartographies: Mapping Inter-relations of the Odeimin Runners Club. Interact. Film. Media J. 2022, 2, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozak, N. Lights, Camera, Resources: The Cinematic Footprint; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cubitt, S. Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, L.U.; Clark, J.L.; Oleksijczuk, D.; Hilderbrand, L. Streaming Media’s Environmental Impact. States Media Environ. 2020, 2, 17242. Available online: https://mediaenviron.org/article/17242-streaming-media-s-environmental-impact (accessed on 20 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Shukin. N. Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parikka, J. Geology of Media; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Litvintseva, S. Geological Filmmaking: Seeing Geology Through Film and Film Through Geology. Transformations 2018, 32, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenblume, K.t. The Failures of Farming and the Necessity of Wildtending; Macska Moksha Press: Clif, NM, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond, C. How to Look at Plants? In Expanded Nature: Ecologies of Experimental Cinema; Della Noce, E., Murari, L., Eds.; Light Cone: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pick, A. ‘Nothing now but kestrel’: Simone Weil, Iris Murdoch and the Cinema of Letting Be. Iris Murdoch Rev. 2017, 8, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pick, A. Vegan Cinema. In Thinking Veganism in Literature and Culture; Quinn, E., Westwood, B., Eds.; Palgrave: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Pick, A. Cinema as Metaxu. The Jugaad Project. 8 September 2020. Available online: https://www.thejugaadproject.pub/home/cinema-as-metaxu (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Salmón, E. Kincentric Ecology: Indigenous Perceptions of the Human–Nature Relationship. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Trash and Treasure: The Gleaners and I. Senses of Cinema. December 2002. Available online: https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2002/feature-articles/gleaners/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- King, H. Matter, Time, and the Digital: Varda’s The Gleaners and I. Q. Rev. Film. Video 2007, 24, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, M. Is It Ethical to Eat Plants? Parallax 2013, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, A.; Demaria, F.; Acosta, A. Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy. Development 2015, 57, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussy, F.D. L’image chlorophyllienne ce la grâce chez Simone Weil [The Chlorophyllic Image of Grace in Simone Weil]. Spaz. Filos. 2016, 17, 337–349. Available online: https://www.spaziofilosofico.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/de-Lussy1.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Telengut, A. Personal communication, 12 August 2022.

- Thomas, D.S. Applying One Dish, One Spoon as an Indigenous research methodology. AlterNative 2022, 18, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayuga Nation’s Official Website. Available online: https://cayuganation-nsn.gov/index.html (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Lytwyn, V.P. A Dish with One Spoon: The Shared Hunting Grounds Agreement in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Valley Region. In Papers of the 28th Algonquian Conference; Pentland, D.H., Ed.; University of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1997; pp. 210–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, P. Personal communication, 10 August 2022.

- Bartlett, C.; Marshall, M.; Marshall, A. Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned with a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 2, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahgee, A.; Schlums, D.E. Personal communication, 30 January 2022.

- Dymond, C. New Growth: To Film Like a Plant. Ecocene Cappadocia J. Environ. Humanit. 2021, 2, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krampen, M. Phytosemiotics. In Essential Readings in Biosemiotics: Anthology and Commentary; Favareau, D., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2010; pp. 257–278, 266. [Google Scholar]

- Simard, S.W. Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory. In Memory and Learning in Plants; Baluska, F., Gagliano, M., Witzany, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 191–214. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond, C. Following Plants: An Interview with Karel Doing. In Edge of Frame: A Blog about Experimental Animation; 2022, forthcoming. Available online: https://www.edgeofframe.co.uk/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Doing, K. Phytograms: Rebuilding Human-Plant Affiliations. Animat. Interdiscip. J. 2020, 15, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymond, C. Media of Devotion: Four Films by Alisi Telengut. Millenn. Film. J. 2022, 76, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Telengut, A. Solitude. Canada. 2016. Available online: https://vimeo.com/159596226?embedded=true&source=vimeo_logo&owner=3561872. (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Sarangerel. Riding Windhorses: A Journey into the Heart of Mongolian Shamanism; Destiny Books: Rochester, VT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, J. Surrender: Mid-Life in the American West; Fitzcarraldo Editions: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, J.; Death of a Radical Rewilder. Literary Hub 20 May 2020. Available online: https://lithub.com/death-of-a-radical-rewilder/. (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Dickinson, E. The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson; Johnson, T.H., Ed.; Little, Brown, and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Canudo, R. The Birth of a Sixth Art. In French Film Theory and Criticism: A History/Anthology, Volume I.; Abel, R., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, A. Personal communication, 6 August 2022.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pick, A.; Dymond, C. Permacinema. Philosophies 2022, 7, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7060122

Pick A, Dymond C. Permacinema. Philosophies. 2022; 7(6):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7060122

Chicago/Turabian StylePick, Anat, and Chris Dymond. 2022. "Permacinema" Philosophies 7, no. 6: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7060122

APA StylePick, A., & Dymond, C. (2022). Permacinema. Philosophies, 7(6), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7060122