In this section, I show that axiological retributivism faces the desert-neutrality paradox. In terms of structure, this paradox is like the neutrality paradox, and the possible responses to the desert-neutrality paradox for retributivists parallel the possible responses to the neutrality paradox. However, there are two differences between these paradoxes. First, whereas the neutrality paradox concerns the goodness of an outcome with respect to its wellbeing distribution, the desert-neutrality paradox concerns the goodness of an outcome with respect to desert. I will, however, continue to assume that the betterness relation has the formal properties Broome claims it has, as well as Broome’s definitions of ‘equally as good as’ and ‘worse than’. In what follows, I will mostly dispense with the cumbersome locution ‘better than with respect to desert’ and will instead simply use ‘better than’. However, readers should interpret instances of the latter as having the meaning of the former. The same goes for instances of ‘worse than’ and ‘equally as good as’. Thus, readers should keep in mind that my claims in this section are about desert value, not all-things-considered value.

The second difference between the neutrality and desert-neutrality paradoxes is that the latter poses a bigger problem for retributivism than the former poses for population axiology. The neutrality paradox is not so paradoxical that it should lead to skepticism about population axiology or to the conclusion that there can be no adequate general population axiology. But I assume that the theoretical cost of abandoning population axiology altogether is much greater than that of simply rejecting the intuition of neutrality. However, I think, the desert-neutrality paradox does support skepticism about axiological retributivism. Indeed, it seems to put significant pressure on axiologists to reject retributivism and retreat to a weaker position concerning the axiological significance of desert.

4.1. Retributivism and Comparisons of Existence and Non-Existence: Setting up the Paradox

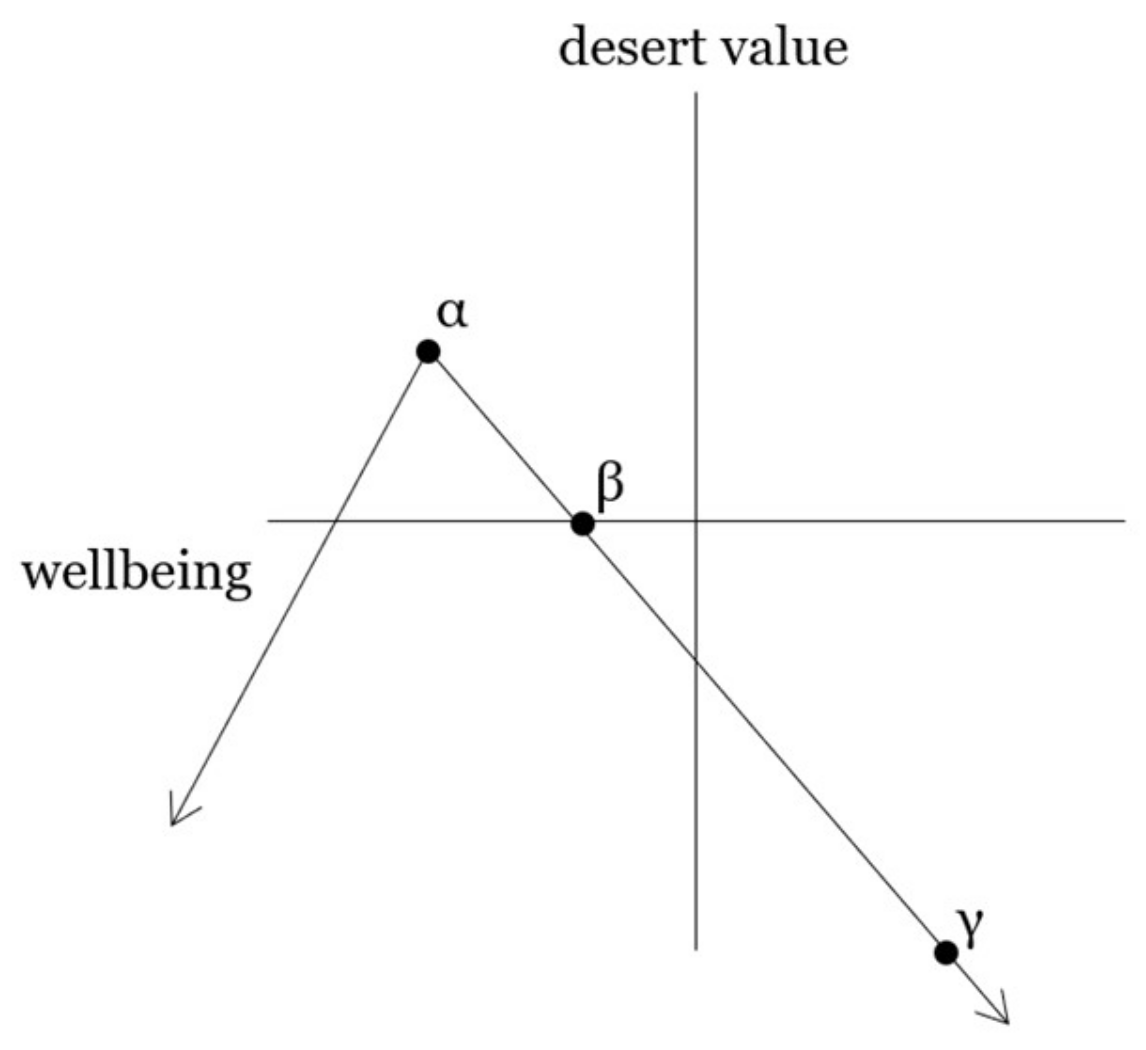

In

Section 1, we took Hitler as our example of an evil person who deserves what is bad for him (suffering), and we assumed a hypothetical desert function for Hitler, illustrated in

Figure 1. The peak of the desert function is the negative wellbeing level α. This is what Hitler perfectly deserves. Although Hitler’s existence at level α is bad for him it is good. Also represented in the desert graph is something that is good for Hitler but bad, namely existence at the very high positive wellbeing level γ, as well as something that is bad for Hitler but neutral, namely existence at the negative wellbeing level β, which is in between level α and level γ.

Our question is whether the desert graph in

Figure 1 can plausibly represent evaluative comparisons of outcomes in which Hitler exists and those in which he does not exist. Let us first assign neutral desert value to a person’s non-existence; that is, assume that the non-existence of a person by itself is neither good nor bad but neutral. (For now, we will refrain from any specific interpretation of the relevant sense of neutrality.)

Next, let us consider some comparisons. Suppose we compare outcome A, in which Hitler never exists, with outcome A-, in which Hitler exists at the very high positive wellbeing level γ. Suppose that apart from Hitler’s existence, A and A- are equally good. This might be difficult to imagine. An outcome such as A, in which Hitler does not exist, would not have any of Hitler’s evil deeds. That would seem to make A much better than A- in many respects, including desert. However, we can imagine that A has other evil deeds that do not occur in A-, and that the evil deeds in A and A- are equally bad, so that the only relevant difference between A and A- with respect to desert value is Hitler’s existence in A- at level γ, and his non-existence in A. It seems Hitler’s existence at level γ in A- is a bad-making feature of A- and that, since A and A- are otherwise equally good, A- is worse than A. More generally, if we are axiological retributivists, we should accept

The badness of additional undeserved good lives. The addition of an evil person with a level of wellbeing that is much higher than what he perfectly deserves makes an outcome worse, other things being equal.

If we accept this claim, we should think that desert graphs as in

Figure 1 plausibly represent at least some comparisons of a deserving agent’s existence with his non-existence.

Next, compare A with a different outcome, A+, in which Hitler exists at the negative wellbeing level β. This is the level at which Hitler’s existence has neutral desert value; he gets a lot of the suffering he deserves, but less than what he perfectly deserves. According to the graph, this is neither good nor bad but neutral. Again, we assume that apart from Hitler’s non-existence in A and his existence at level β in A+, A and A+ are equally good. We should conclude that Hitler’s existence at level β in A+ makes A+ neither better nor worse than A. With respect to desert, it is a neutral addition. This conclusion makes sense given our assumptions that Hitler’s non-existence has neutral desert value and that his existence at level β also has neutral desert value.

Finally, compare A with yet another outcome, A++, in which Hitler exists at the negative wellbeing level α. An existence at level α is what Hitler perfectly deserves. Apart from Hitler’s existence in A++ and his non-existence in A, these outcomes are equally good. How do A and A++ compare with respect to desert? We stipulated that Hitler’s non-existence is neutral, and the desert graph in

Figure 1 tells us that it is good if Hitler gets what he perfectly deserves. From these claims, we should conclude that A++ is better than A. An outcome in which Hitler exists and experiences all of the suffering he perfectly deserves is better than an outcome in which Hitler never exists, other things being equal.

But this conclusion is very counterintuitive. When I wear my retributivist hat, I find that A++ is not better than A.

3 If we are retributivists, we might think that if Hitler exists and commits certain evil deeds, then it is good if he experiences the suffering he perfectly deserves. But is it really better in any respect if Hitler comes into existence and experiences that suffering? Would it really be worse if Hitler simply never existed?

In answering this question, we should not focus on the intrinsic badness of Hitler’s atrocities. Our question is about the value of Hitler getting what he deserves. To focus your intuitions, consider a world in which Hitler gets all of the suffering he perfectly deserves. Suppose that in this world we also have a machine that can perfectly replicate Hitler as he was toward the end of his life. The replica would be just as evil as the original and would wholeheartedly endorse the original’s wrongdoing. It would also be true of the replica that if he were, or had been, in Hitler’s position, he would have committed all of the same atrocities. After creating the replica, we could ensure that it gets all of the suffering it perfectly deserves. Would it make things better in any respect to create the replica and punish it? I think not. This is not the case just due to the fact that the replica would (technically) be innocent of Hitler’s actual crimes. Perhaps being extremely evil and wholeheartedly endorsing Hitler’s crimes by itself warrants some form of punishment, such as (at least) a hard slap on the wrist. Still, I would not think that creating and punishing the replica would be, in any respect, an improvement. A retributivism that implies that it is better in some respect that an evil suffering person exists seems unpalatably sadistic. It goes too far.

But retributivists must also say that the addition of an evil person who gets the suffering he perfectly deserves does not make the outcome worse. For there is no retributivist rationale for the claim that the addition of such a person diminishes overall desert value. Hence, if we are axiological retributivists, we should want to accept

The neutrality of additional perfectly deserved bad lives. The addition of an evil person with the negative wellbeing that he perfectly deserves makes an outcome neither better nor worse, other things being equal.

Unfortunately, retributivists cannot easily accommodate this claim. This is because they believe that some perfectly deserved lives with negative wellbeing have positive desert value. Accepting the claim stated above therefore puts retributivists in the difficult position of explaining how lives with positive desert value can be desert-neutral additions (i.e., additions that make the outcome neither better nor worse with respect to desert). This is exactly like the problem at the heart of the neutrality paradox considered in

Section 2.

4.3. Desert Neutrality as Incommensurateness

Suppose one rejects desert-neutrality as equal goodness. One can still claim that the addition of an evil person who gets what he perfectly deserves is neutral—that it makes things neither better nor worse. Ruth Chang, for example, has argued for the existence of a value relation that cannot be identified as one of the three standard relations, ‘better than’, ‘worse than’, and ‘equally as good as’ [

15]. Retributivists might interpret desert-neutrality in terms of such a fourth value relation.

There are many alleged examples of a thing being neither better than, worse than, nor equally as good as another with respect to some evaluative dimension. Who was a better composer, Mozart or Debussy?

4 Some music lovers might favor one over the other. Yet, a reasonable person might, after careful reflection, decide that neither is better than the other, but also that the two are not

equally good. When one considers the specific music-related values that make each composer great, for example Mozart’s technical precision and Debussy’s creative rebelliousness, one might be unable to make precise tradeoffs between these values, even if one were to somehow know all of the relevant facts about them. Following Broome, let us define ‘x is incommensurate with y’ (with respect to some value) to mean that x is neither better nor worse than y, nor equally as good as y (with respect to that value) [

8] (p. 165).

5 Mozart and Debussy are incommensurate (with respect to their values as composers) just in case Mozart is neither better, nor worse, nor equally as good (a composer) as Debussy.

Two outcomes might be incommensurate with respect to desert. Is it better with respect to desert that a hundred evil people experience all of the suffering that they perfectly deserve or that one good person experiences most, but not quite all, of the joy and life satisfaction that she deserves? The comparison might be difficult to determine since the two outcomes differ both with respect to the number of deserving agents and with respect to the amounts of wellbeing that they deserve. Even if one were to know all of the relevant facts about the people in these two possible outcomes, the nature of their deeds, their specific vices and virtues, and so forth, one might find that neither outcome is better than the other with respect to desert and yet that the two outcomes are not equally good with respect to desert [

2] (pp. 600–609). One might think that in this case there are two different desert values, the value of evil people getting what they deserve and the value of good people getting what they deserve, and that these values cannot always be precisely compared.

There is an important feature of incommensurateness that is crucial to the success of any solution to the desert-neutrality paradox that interprets desert-neutrality in terms of incommensurateness. This is that, unlike equal goodness, incommensurateness is not transitive. That is, it is not the case that if x and y are incommensurate and y and z are incommensurate, then x and z are also incommensurate. (We will see why this matters shortly.) Notice that whenever it seems that one thing x is incommensurate with another thing y, it also seems that x is incommensurate with some third thing y+ that is clearly better than y. Suppose we think that a certain outcome O1, in which a hundred evil people experience all of the suffering they perfectly deserve, is incommensurate with an outcome O2, in which a single person gets most, but not all, of the good things that she perfectly deserves. Then we will probably also think that O1 is incommensurate with another outcome, O3, that is exactly like O2 except that the single good person in O3 has all of what she perfectly deserves in virtue of having slightly more of the good things she deserves than she has in O2. Clearly, O3 is better than O2. Yet O3 may still seem incommensurate with O1. A slight improvement in one of two incommensurate outcomes does not necessarily render the former better than the latter. But now we seem to have the following result: O2 and O1 are incommensurate, and O1 and O3 are incommensurate, but O3 is better than, and hence, not incommensurate with, O2.

We are now in a position to see how an appeal to incommensurateness might help retributivists avoid the desert-neutrality paradox. Suppose retributivists interpret the desert-neutrality claim in terms of incommensurateness. That is, suppose they say that the addition of a deserving person at a wellbeing level within the desert-neutral range results in an outcome that is incommensurate with an outcome in which this person does not exist, other things being equal. They can now avoid the problem described in

Section 4.2. Recall that if we interpret desert-neutrality in terms of equal goodness, we must accept (6) A+ is equally as good as A, and (7) A++ is equally as good as A. These two claims, together with the transitivity of ‘equally as good as’ entail (8) A+ is equally as good as A++, which implies (9) A++ is not better than A+, which is inconsistent with retributivism. But if we interpret desert-neutrality in terms of incommensurateness, then we will reject (6) and (7) and replace them with

- (6′)

A+ and A are incommensurate

and

- (7′)

A++ and A are incommensurate.

The conjunction of (6′) and (7′) does not imply (9). One cannot infer from (6′) and (7′) that A++ and A+ are incommensurate, since, as we just saw, unlike ‘equally as good as’, ‘is incommensurate with’ is not transitive.

However, this is not the end of the story. As Broome has shown, interpreting the neutrality of a person’s existence as incommensurateness has problems. Broome illustrates these problems in the context of comparing different outcomes in terms of their different distributions of wellbeing [

8] (pp. 169–170). But the same problems arise in the context of comparing different outcomes in terms of their desert values, as I shall now demonstrate.

One problem is that the appeal to incommensurateness is ad hoc. All of the examples that support the existence of incommensurateness involve comparisons in which one thing is better than another in some respect R1 but worse in some different respect R2. (Think of the legal and academic careers considered above.) It is because the tradeoff between R1 and R2 cannot be made with precision that we cannot say that either thing is better or that they are equally good. But comparisons of existence and non-existence are not like this. There is no reason to think that the addition of Hitler by itself leads to incommensurateness, apart from the fact that if this were true, we would avoid the problem in

Section 4.2.

The second problem that Broome raises for treating the neutrality of personal existence as incommensurateness is that it fails to adequately capture our intuitive idea of neutrality:

Suppose two things happen together. One is bad, and the other neutral. Intuitively, the net effect of the two things should be bad. A bad thing combined with a neutral thing should be bad. Intuitively, neutrality cannot act against badness to cancel it out, so the net effect should not be neutral [

8] (p. 169).

Assuming that Broome would say the same thing about the combination of a good thing and a neutral thing, the general idea to which he appeals here is what I will call

The spirit of neutrality: A bad thing plus a neutral thing is a bad thing. Similarly, a good thing plus a neutral thing is a good thing.

According to Broome, an interpretation of the neutrality of a person’s existence in terms of incommensurateness violates the spirit of neutrality, and hence, must be rejected.

To illustrate this violation in the context of desert value, consider the four outcomes represented in

Figure 4:

This is similar to the previous example, except for the following difference. There is another evil character, Stalin, who exists in all four of the designated outcomes, B, C, D, and E. Stalin gets what he perfectly deserves in B and C; but in D and E, he exists at a wellbeing level, level β, that is slightly higher than what he perfectly deserves. Therefore, with respect to Stalin’s desert, D and E are slightly worse than B and C. However, Hitler gets what he perfectly deserves in D, an existence at level α, so with respect to Hitler’s desert, D is better than C. Let us stipulate that the welfare difference for Hitler between C and D has a greater impact on desert value than the welfare difference for Stalin, and that therefore with respect to desert,

- (11)

D is better than C

and hence, by definition,

- (12)

C is worse than D.

Retributivism clearly entails

- (13)

B is better than E.

(The only relevant difference between B and E is that Stalin gets what he perfectly deserves in B but not in E.)

The proposal we are considering is that desert-neutrality is incommensurateness. On this proposal, since wellbeing levels α and β are both within the desert-neutral range,

- (14)

C and B are incommensurate

and

- (15)

D and E are incommensurate.

Here is where things get troublesome. Could D be worse than B? Apparently not. If D were worse than B, then from (12) and the transitivity of ‘worse than’ we could infer

- (16)

C is worse than B.

But then C and B couldn’t be incommensurate as (14) states. Hence, we must instead accept

- (17)

D is not worse than B.

Similarly, we must accept

- (18)

D is not better than B.

Why? Because the claim that D is better than B, as well as (13) and the transitivity of ‘better than’ jointly entail

- (19)

D is better than E.

But then D and E couldn’t be incommensurate as (15) states. We cannot say that D is equally as good as B either, since from this claim and (13), and our definition of ‘equally as good as’, we get (19), which, as we just saw, contradicts (15). Hence, we must accept

- (20)

D is not equally as good as B.

Notice that (17), (18), and (20) together rule out the possibility of B and D standing in the relations ‘better than’, ‘worse than’, or ‘equally as good as’. So, it seems we must accept

- (21)

B and D are incommensurate.

But (21) is inconsistent with the spirit of neutrality. D is worse than B with respect to Stalin’s desert. We are assuming that the existence of Hitler in D makes D neither better nor worse than B. But these are the only two relevant differences between B and D. Hence, overall, D should be worse than B. A bad thing plus a neutral thing should amount to a bad thing. If D is incommensurate with B, despite being worse in one respect and neither better nor worse in another respect, then incommensurateness is, to use Broome’s phrase, “greedy”. It is a kind of neutrality that can “swallow up” bad things, or losses of good things.

One could respond to this objection to desert-neutrality as incommensurateness by rejecting the spirit of neutrality. For example, one might doubt Broome’s claim that the spirit of neutrality captures our intuitive idea of neutrality. One reason to doubt Broome’s claim is that our intuitive idea of neutrality seems logically compatible with the existence of organic unities, i.e., entities that possess a kind of holistic value that depends not only on the values of its parts but also the relations between these values. If there are organic unities, then presumably some are incompatible with the spirit of neutrality. Here is a putative example. If a certain person is in a Zen-like state and exhibits no emotional response whatsoever to what he observes, then this might be a neutral thing (neither good nor bad). If a certain child takes its very first steps, then this might be a good thing. But if a certain person exhibits no emotional response whatsoever to his child taking its first steps, then this may not be a good thing. It may instead be a bad thing, or perhaps a neutral thing. In this case, a certain neutral thing and a certain good thing might combine to yield something that is not good. The spirit of neutrality rules out the existence of such organic unities; it implies that a neutral thing and a bad (or good) thing cannot combine to yield anything other than a bad (or good) thing.

However, in the context of evaluating desert-neutrality as incommensurateness, this response is a red herring. Although Broome appeals to the spirit of neutrality, one need not appeal to this general claim to find fault with the interpretation of desert-neutrality as incommensurateness. One needs only the weaker claim that in the comparison of B and D, if the existence of Hitler in D is a neutral addition, and if D is worse than B with respect to Stalin’s desert, and if other things are equal, then D is worse than B. This claim is only about two specific outcomes, B and D, so it does not rule out the existence of organic unities. Moreover, it is hard to see how the two differences just mentioned could fail to make D worse than B. Even if a bad (or good) thing and a neutral thing can sometimes amount to a neutral thing, we require an explanation of this wherever it happens. For example, in the case of the emotionless person observing his child taking its first steps, the explanation of how the neutral emotionless response and the good taking of first steps together amount to something neutral might be that there is some badness in failing to have the appropriate joyful response to the good event of one’s child taking its first steps, and that this badness is equal in degree to the goodness of that event, such that the conjunctive state of affairs is neutral overall. But in the comparison of B and D, there is no explanation of this kind. Proponents of desert-neutrality as incommensurateness lack a principled explanation of desert-neutrality’s greediness.

4.4. The Conditional Goodness of Deserved Suffering

Another option for retributivists is to try to explain the desert-neutrality claim in terms of the conditional goodness of deserved suffering. Conditional goodness is different from overall goodness. That x is good conditional on y entails that (y and x) is better than (y and not x) but (not y and x) is equally as good as (not y and not x), and moreover, (y and x) is equally as good as (not y and not x); in other words, the goodness of x is neutral with respect to whether the condition, y, obtains. As we saw earlier, this is how some philosophers, such as Narveson, think of a person’s wellbeing [

10]. They think that if a person exists, it is better if she has more wellbeing; but they also think that it is not better if she exists in the first place and has positive wellbeing. The goodness of her wellbeing is conditional on her existence, and hence, is neutral with respect to whether she exists.

Retributivists can say something similar about the goodness of an evil person’s suffering. They can say that this goodness is neutral with respect to whether the evil person exists. This avoids the uncomfortable result that it is better, other things being equal, if an evil suffering person comes into existence. Moreover, unlike the appeal to incommensurateness, the appeal to conditional goodness is not ad hoc.

However, there is a problem with understanding the goodness of deserved suffering as being conditional on an evil person’s existence. It is basically the same problem that Broome raises for understanding the value of a person’s wellbeing as conditional that person’s existence [

8] (pp. 152–157). It is hard to see how to fit the conditional goodness of deserved suffering into a coherent ordering of outcomes with respect to their overall desert value. To see this, consider the outcomes represented in

Figure 5.

In

Figure 5, as in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, level α and level β are denoted.

Figure 5 also represents two of the outcomes featured in the previous case, C and D. B′ is similar to the outcome B featured in the previous case, except that in B′ Stalin is slightly better off than he is in B, hence, in B′ what Stalin gets is slightly better for him than what he perfectly deserves. As in the previous case, Stalin gets what he perfectly deserves in C and Hitler gets what he perfectly deserves in D. Moreover, as in the previous case, although D is worse than C with respect to Stalin’s desert, it is better than C with respect to Hitler’s desert, and we stipulate that the latter consideration outweighs the former, and hence,

- (11)

D is better than C.

The conditional goodness of deserved suffering implies

- (22)

D is equally as good as B′.

The only difference between D and B′ is that Hitler exists in D and gets the suffering he perfectly deserves, but he does not exist in B′. The conditional goodness of Hitler’s perfectly deserved suffering is neutral with respect to whether Hitler exists.

Since Hitler’s deserved suffering is only a conditional good, with respect to Hitler’s deserved suffering, C is equally as good as B′. But with respect to Stalin’s deserved suffering, C is better than B′. It therefore seems that overall, with respect to desert

- (23)

C is better than B′.

But (23) and (11), and the transitivity of ‘better than’ imply

- (24)

D is better than B′.

This contradicts (22), which follows from the conditional goodness of deserved suffering.

If ‘better than’ is transitive, then the pursuit of the conditional goodness of deserved suffering leads to a dead end. That is bad news for axiological retributivists, for it is plausible that if deserved suffering can be intrinsically good, then its intrinsic goodness is conditional on the existence of the deserving person.