1. Introducing the Standard View of Deserved Penalties

Roughly, according to the desert theory of legal punishment, a political organization, such as a state, ought to intentionally harm or subordinate people because they have done something in the past with a negative valence, such as broken a just law that merits a similar response, i.e., one of a negative kind with a comparable degree. It is one instance of a family of what may be broadly called ‘retributive theories’, which base the justification of legal punishment principally on facts about the past as opposed to its expected consequences in the future. The idea that it is right to punish someone because he deserves it differs from the idea that it is right because he unfairly took an extra liberty, relative to law-abiding citizens, that state punishment would remove [

1,

2] (hence we use the term 'desert' more narrowly than, e.g., George Sher, who discusses the fairness theory in the context of his book titled

Desert [

1] (pp. 69–90)) or because the state must use punishment to treat offenders as responsible and stand up for the victims [

3] (pp. 95–118) and [

4]. The correction of unfairness and the expression of disapproval have a retributive or backward-looking logic, but we set these theories aside and focus strictly on the imposition of desert.

A complete specification of a desert theory of legal punishment would tell us why the state should punish people, which people it should punish, how it should punish them, and how much punishment they should receive. In this article, we principally seek to answer the last question about the right quantity of punishment, which is distinct from the quality it should take. Thus, we do not address whether punishment should take the form of death, corporal penalties, imprisonment, fines, labour, or public humiliation, instead supposing (with the overwhelming majority of the field) that these kinds of penalties can be compared in terms of their amounts of harm or subordination and addressing the question of how much is just for a given crime.

Unquestionably, there has been a standard account of how much harm/subordination is deserved for a crime, namely, a proportionate degree. Harking back at least to Aristotle [

5] (pp. 1131a–1131b) and, somewhat more recently, Kant [

6] (Ak. pp. 331–337), the dominant view has been that a person deserves a penalty that is proportionate to the crime that he committed, i.e., that in some way matches or fits the nature of his crime. Below, we acknowledge that there have been different ways of understanding what proportionality involves, but we maintain that proportionality has been the determinative concept. Indeed, it is not infrequent to encounter those who

define the ‘desert theory’ and cognate terms as including a proportionality requirement (clear instances of those who define ‘desert theory’ or related terms such as ‘retributivism’ (meant to connote desert) in terms of proportionality include [

7] (pp. 457, 459, 489n100) and [

8] (p. 61)). According to this approach, it is a conceptual truth that deserved penalties are proportionate, such that it would be logically contradictory to posit non-proportionate penalties as deserved.

In this article, we argue in effect that this conceptual analysis is flawed; there is in fact logical space for something to count as a deserved penalty that is not proportionate. However, our aims go beyond simply getting the meanings of terms (or analyses of concepts) right, and instead, they center on broadening the field’s awareness of the options available to a desert theorist in respect of how much to punish. We articulate two new desert-based alternatives to the proportionality account and, moreover, provide strong reasons to favor them over it.

In the following, we begin by recounting the basics of how desert theorists have typically answered the question of how much to punish in terms of proportionality (

Section 2). Then, we argue that the heart of the amount of a deserved penalty is not one that is proportionate but rather that tracks proportionality (

Section 3). We articulate two alternatives to the standard view, and we show that they are comparably motivated by the considerations that move philosophers to reject forward-looking theories of sentencing in favor of proportionality. In the following section, we show that non-proportional approaches to deserved penalties have important advantages relative to proportionality, including that they can uniquely entail that all deserved penalties are possible, avoid counterintuitive implications about barbarism, and cohere with intuitions about positive desert (

Section 4). We conclude by addressing one natural objection that adherents to the standard view would be sure to make and by suggesting some topics for further reflection, supposing that non-proportionate desert is to be taken seriously (

Section 5).

2. Proportionality as Central to Desert in the Philosophy of Punishment

In this section, we recount the main respects in which desert theorists have analyzed the just amount of punishment in terms of proportionality and reasons why they have found proportionality compelling. The points will be familiar to those who know the literature that addresses how to make the severity of punishment match the gravity of the offense, but we must spell them out to make our target clear and, most importantly, to show that non-proportionate accounts of desert can capture what motivates most people to hold the standard, proportionality account.

Among laypeople, deserved penalties are frequently conceived in terms of lex talionis, the law of retaliation that is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and the Qur’an. Summed up with ‘an eye for an eye’, the principle states that deserved penalties are precisely those harms that offenders have inflicted on victims.

Even if Kant expresses support for

lex talionis [

6] (Ak. pp. 332–333), relatively few contemporary philosophers of punishment work with it, whether they hold the desert theory or are criticizing it in a charitable way. There are well-known problems with

lex talionis, particularly concerning the fact that some misbehavior simply cannot be done to the guilty. How is one to adhere to this account of how much punishment is deserved for taking someone’s eye when the offender is already blind? How is one to punish drunk driving that harmed no one by appeal to

lex talionis? Someone who counterfeits? Someone who failed to register his car? A necrophiliac?

The point is not that these actions do not deserve to be punished (although that sort of case has been made for some of them); it is rather that they might well deserve to be punished but that lex talionis appears indeterminate in respect of how we are to do so. It provides no guidance when a criminal act has not caused a specific harm to a living individual or when that specific harm cannot be inflicted on the criminal.

Another well-known problem with lex talionis is that, on the face of it, it does not take into account the offender’s state of mind. Most believe that intentionally trying to run over an innocent pedestrian is a worse crime and deserves a greater penalty than running over an innocent pedestrian because one forgot to have one’s brakes checked. A plain reading of the principle, though, suggests that death would be a just penalty in both cases by virtue of the actus reus, regardless of the nature of the mens rea.

Most contemporary interpreters of desert theory have found another way to analyze proportionate penalties that plausibly avoids the two problems of indeterminateness and the failure to take mens rea into consideration. It involves positing degrees of wrongdoing and degrees of culpability (or blameworthiness or responsibility), where the right amount of punishment (P) is equal to the product of however wrong (W) the offender’s act was multiplied by however culpable (C) he was for the act. Wrongness centrally consists of the sort of harm produced by the token or type of the act, but it could include violations of rights and disrespectful treatments that have not caused or even risked harm. Culpability is centrally understood to be the respect in which the crime was part of the offender’s plan (e.g., intended versus negligent) and the extent to which it was within the agent’s control, but several desert theorists also include the agent’s motives for performing the act. In principle, one could rank all these elements with cardinal numbers, where the deserved penalty is a product of how wrong the crime was multiplied by how culpable the criminal was for it.

Note that this approach prescribes an amount of punishment, but it says nothing about the type, not requiring the imposition of the same sort of harm the offender had inflicted on his victim. Hence, it can easily prescribe a penalty for a blind person who has blinded someone else, as well as for crimes that do not involve specifiable harms, such as drunk driving, counterfeiting, and failing to register one’s car, so long as these are all wrongful acts (as they intuitively are).

One encounters this broad understanding of how much to punish repeatedly among those sympathetic towards desert theory over the past 50 years (e.g., in [

7] (pp. 483–488), [

8] (pp. 3, 61), [

9] (pp. 127–128), [

10] (pp. 60–63), [

11] (pp. 45, 64–74), [

12] (pp. 206, 226), [

13] (pp. 80–84, 173–174), [

14] (pp. 75–77), and [

15] (pp. 24, 29, 33, 42). In the following, we take a ‘W x C = P’ formula to be the most promising instance of a proportionality principle (tweaking Robert Nozick’s formula of ‘r × H = R’ (responsibility multiplied by harm equals retribution owed) in [

10] (pp. 60–63)), although our criticisms of it will apply with comparable force to

lex talionis or any other plausible specification of it. (There is a third kind of proportionality that is familiar to retributivist thinkers, but it is a function of how much the offender gained from the crime, not of how much (roughly) the victim lost from it. Such an approach is more apt for the fairness theory, according to which the point of punishment is to remove an unfair advantage taken by the offender in the course of breaking a just law. See [

2].)

Note that the W × C = P conception of how much punishment is deserved, and in fact any specification of proportionality, is neutral among the different moral frameworks that might prescribe giving people what they deserve. Thus, for example, some believe that deserved penalties are good for their own sake and should be maximized in a consequentialist fashion. In that case, the state should do whatever it would take to see that penalties equivalent in magnitude to W × C are meted out as much as possible in the long run. In contrast, others hold that there is a deontological obligation to impose deserved penalties, perhaps as a Rossian prima facie duty or as a way of expressing respect for persons à la Kant. In that case, the state has some moral obligation when it comes to a given offender to mete out a penalty equivalent in magnitude to W × C, which might or might not be outweighed by another obligation. Parallel remarks apply to virtue-based views, according to which meting out desert is appropriate since it would make one a better person to do so. An account of proportionality is an analysis of what is deserved, not of why it is morally appropriate to impose what is deserved, which is a separate debate.

On the face of it, some kind of proportionality principle seems unavoidable if one wants both to avoid and to explain four stock objections to utilitarianism, self-defense theory, moral education theory, and other forward-looking views that justify punishment based on its expected consequences for crime control. For one, it would be wrong to punish morally innocent people at all, even if doing so would deter other people from committing crime. It might seem (as it does to one scholar [

8] (p. 3)) that only a proportionality principle can make sense of why: it would be disproportionate to inflict a penalty on someone who has not broken a just law.

For another, it would be wrong not to punish someone guilty of a crime; although there can be conclusive reasons not to do so, say, in cases of double jeopardy, there is always some injustice in the acquittal of a person who has broken a just law. Proportionality naturally explains why: there is no response of the same (negative) kind (let alone degree) as the offender’s misbehavior.

For a third, it would be wrong to punish a trivial crime with a harsh penalty; failing to use one’s turn signal to indicate when switching lanes merits a penalty but not 20 years in prison, even if that would deter crime and serve to prevent collisions. A natural account of why such a penalty would be wrong is that it would be disproportionate to the crime.

For a fourth, it would be wrong to punish a serious crime with a light penalty; a small fine for murder would be unjust, even if the killer would not commit the crime again and no greater penalty is essential to deter others from killing. Again, disproportionality is a powerful explanation of the injustice.

These are four well-known and compelling objections to forward-looking theories, which are, in effect, four arguments for a proportionality principle. In the light of such considerations, one theorist remarks that ‘the question is not whether or not a theory of punishment ought to provide an account of proportional punishment. Rather, the question is which analysis of proportional punishment is most plausible and why?’ [

8] (p. 3). In the following section, we provide a different explanation for these four objections to forward-looking theories and, by implication, a response to four arguments for a proportionality principle. We demonstrate that there are other ways to account for the above intuitions about just and unjust penalties in terms of desert but apart from proportionality.

3. Two Alternatives to Proportionality

In this section, we begin by raising, only to set aside, one possible alternative to the standard, proportionality account of how much punishment is deserved, after which we advance two proposals that are more promising. At the end of this section, we show that our non-proportionate views capture the motivations for proportionality sketched in the previous section, saving additional argumentation in their favor for the following section.

It is tempting to suggest that the ‘heart’ of a desert-based account of how much to punish is not proportionality but rather the principle that the worse the crime, the greater the penalty should be. Although proportionality implies the latter, ordinal principle, the ordinal principle does not imply proportionality.

However, ordinality is insufficient to capture what motivates desert theory, such that some kind of (quasi-)cardinality is necessary. To see the concern, suppose that the crime of murder receives the highest score with 2000 (where this is the product of wrongness times culpability), a home burglary with a toy gun receives 350, and failing to register one’s car receives a 1. Now, imagine that the state meted out the following penalties for each of these crimes: 30 years in prison for murder, 29 years in prison for the burglary, and a fine of $50 for the failure to register one’s car. Here, the penalties conform to the principle that the worse the crime, the greater the penalty should be, but they are not intuitively just, plausibly because they are not deserved. In particular, if the very worst crime receives 30 years in prison, then a crime that is about a sixth as serious should not receive 29 years, but presumably something more on the order of five years, so the adherent of the standard account of deserved punishment would powerfully suggest.

Another way to see that ordinality is insufficient to ground something sensibly called ‘desert theory’ is that it would allow one guilty of murder to be punished lightly in absolute terms, even if severely on a relative scale. For instance, suppose that the state’s highest penalty for a crime is four years in prison, which is what is meted out to those guilty of murder, while home burglary with a toy gun receives about a year in prison, and failure to register one’s car is fined at

$10 or so. Then, again, we find that the worse the crime, the greater the penalty that is meted out, but this is far from enough to capture what desert theorists characteristically and plausibly have in mind. One scholar strives to show that desert theory is compatible with abolishing the death penalty, since ‘all that it requires is that if murder is the most serious crime, then murder should be punished by the most severe punishment on the scale. The principle does not tell us what this punishment should be, however’ [

14] (p. 77). Our point is that this conception of the proper amount of punishment is not enough to capture the motivation for a desert orientation, where some kind of cardinal fit between the seriousness of the crime and amount of punishment does so much better.

We maintain that these criticisms of a merely ordinal principle are sound but that they do not require us to accept proportionality. We hold that a deserved amount of punishment needs to refer to proportionality and moreover to track it but that it need not be proportionate itself to count as ‘deserved’. Here are two conceptions of amounts of deserved punishment that are more robust than mere ordinality but are not instances of proportionality, even though they do logically depend on it.

The first approach we call the ‘(lower) range view’. According to it, one starts by considering which penalty would be proportionate and then reduces it, prescribing lower and upper limits for a penalty, which are all less than what would be proportionate. Concretely, one might divide the proportionate penalty by 1.33 to 2 and pick within the resultant range of penalties that are three-quarters to a half of what would be proportionate. Although an upper range view is conceivable, we find no substantial motivation for it. (One of us does however think that it should be taken seriously for trivial crimes).

For example, suppose the proportionate penalty for murder has a severity of 2000, while that for a home burglary with a toy gun measures 350. Then, instead of punishing the former with a penalty weighted 2000, the appropriate penalty would be in the range of 1500–1000, while the burglary would be punished with something between 262.5 and 175 instead of 350.

How should a judge choose within the (lower) range? Note that it would not make sense to appeal to aggravating or mitigating factors, since those have already been considered when ascertaining the proportionate penalty in the form of C.

Instead, a judge might pick toward the higher or bottom end of the scale, taking into account the effects of the penalty on the desert of other innocent parties, such as the offender’s family or the victim. If a certain penalty within the range would avoid causing harm to those who do not deserve it or would compensate for harm done to those who did not deserve it, then the approach to sentencing need not be a hybrid model that appeals to, say, crime control considerations.

Andrew von Hirsch discusses two views somewhat similar to the (lower) range view in his influential book

Past or Future Crimes [

11]. There, he addresses a principle from Norval Morris, according to which ‘the concept of desert defines relationships between crimes and punishments on a continuum between the unduly lenient and the excessively punitive, within which the just sentence may be determined on other grounds’ [

11] (p. 39 quoting Morris). Ruling out only what one can clearly ascertain an undeserved penalty to be, a judge is then to use crime control considerations to specify the right penalty within the range. Contra Morris, von Hirsch objects that this principle would permit a less severe crime to end up with a greater penalty than a more severe crime [

11] (pp. 39–43). To avoid this problem, von Hirsch presents an alternative to Morris’ principle, according to which convention [

11] (pp. 43–44) and crime control factors [

11] (pp. 94–95) determine how to begin matching penalties to crimes, although it is afterward not a matter of convention or crime control to determine the proportionate degrees of punishment for other crimes relative to the initial match. For instance, upon having figured out which amount of prison expresses adequate disapproval for burglary and would deter effectively, one can then set proportionate penalties for other crimes relative to that specification. What Morris’ and von Hirsch’s principles have in common is that they are presented as conceptions of how much punishment is deserved, and yet they avoid the strict cardinal proportionality of the W × C = P formula (and also include forward-looking elements, such as crime control).

Note, though, that these principles are not equivalent to the (lower) range view, for the (lower) range view is defined in reference to cardinal proportionality; one starts with W × C = P and then works down. Both Morris and von Hirsch deny that anything like W × C = P is available to the desert theorist, holding that one has to ‘anchor’ the punishment scale without any specific conception of proportionality and, instead, anchor it on ‘non-desert’ factors. (One might want to know why one should favor a conception of desert that is tied to proportionality in the way the (lower) range view is, compared to the principles from Morris and von Hirsch. That is a large question that merits separate treatment. For now, we will say that some reference to proportionality appears to best explain various judgments of lenient or excessive penalties that are more likely to be prescribed, the more that crime control were to figure into ‘anchoring’. In addition, the (lower) range view is simpler and more coherent, appealing only to the avoidance of undeserved conditions, as opposed to bringing in crime control considerations.)

The second non-proportionate approach to understanding a deserved punishment we call the ‘asymptotic view’. According to it, a judge should impose proportionate penalties for a large majority of crimes up until a certain point of seriousness, after which the amount of punishment that should be received should get smaller for each additional relevant unit and diminish asymptotically toward zero.

Thus, supposing the proportionate penalty for serious assault has a severity of 1000, while that for a home burglary with a toy gun measures 350, penalties measuring 1000 and 350 should be meted out, respectively. However, suppose that an offender engages in substantial torture. Then, he should receive a penalty greater than 1000, but not 1750, even supposing the torture were markedly worse than the horrific beating. Instead, the torture would receive not very much on top of the penalty for the beating, say, another 200. Suppose further that another offender engages in murder, which is even worse than torture. Then, he should receive a penalty greater than 1000 and also greater than 1200, but the extra penalty for murder should be less than that given out for the torture, say, 175, for a total of 1375 and so on.

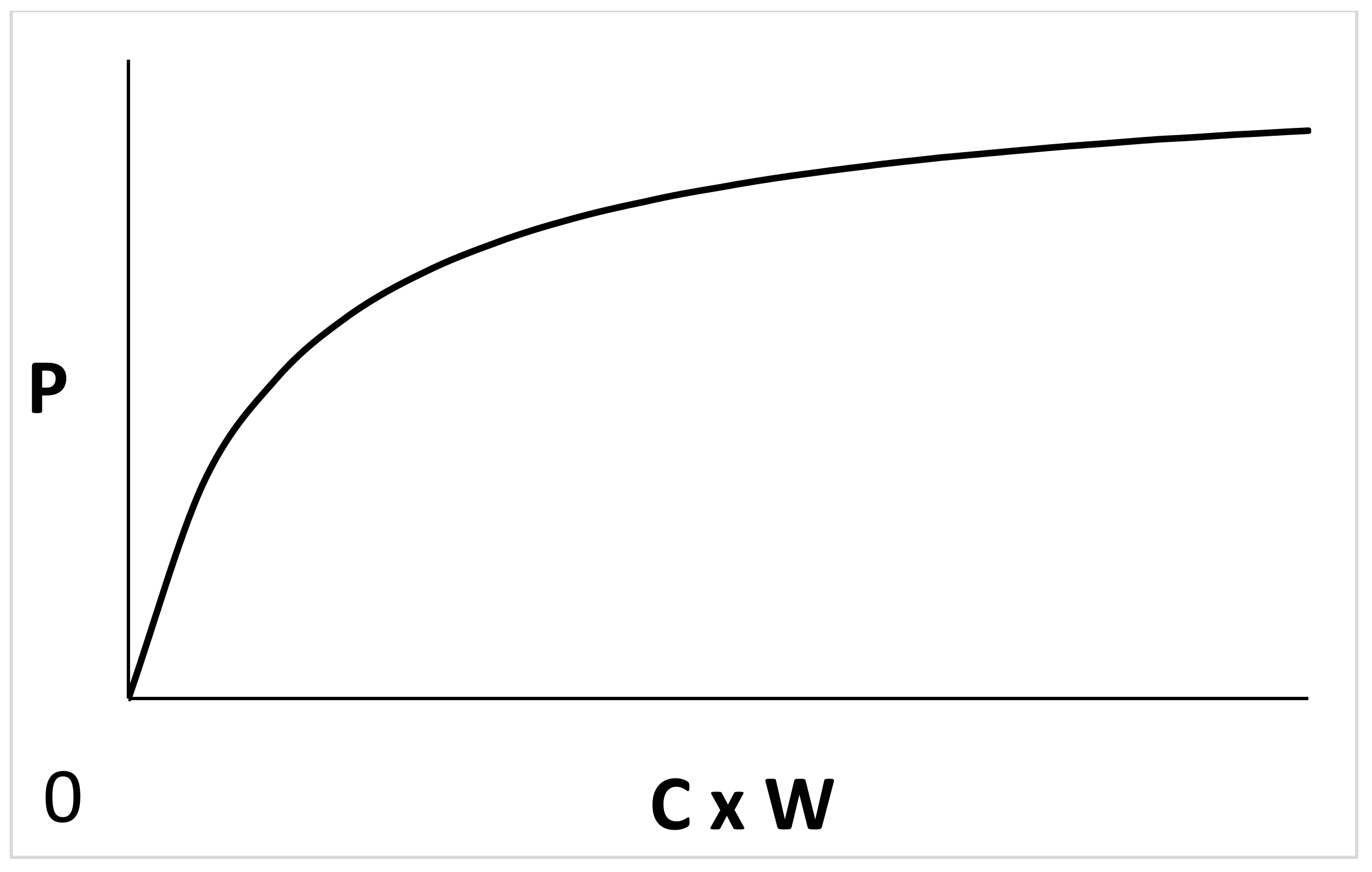

Geometrically speaking, this view could be represented with something like a logarithmic curve on a graph. Consider

Figure 1, where ‘P’ represents amount of punishment and ‘C × W’ the seriousness of the crime.

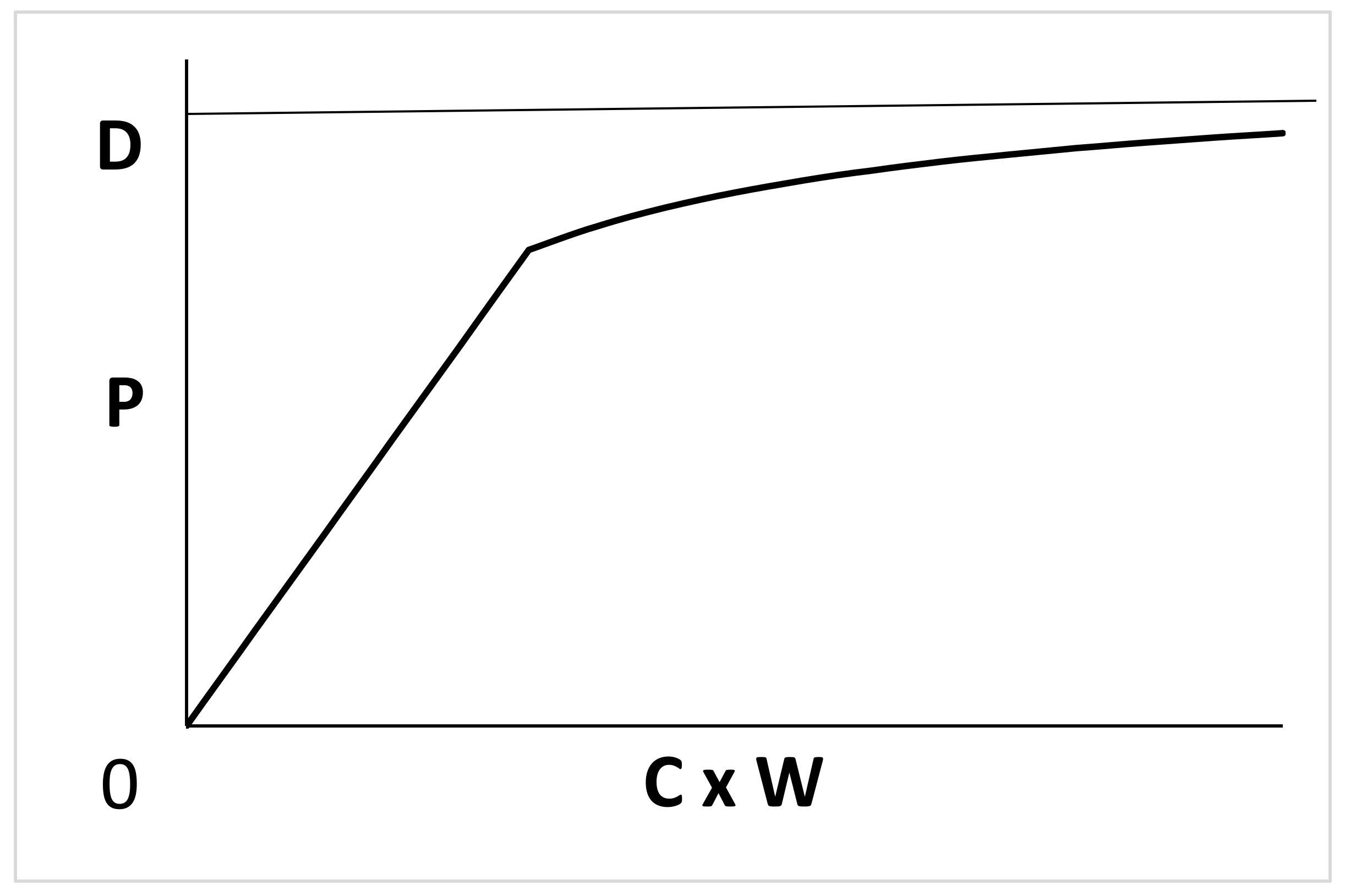

Figure 1 is familiar from geometry (even if not so much from desert theory), but we do not work with it, and, instead, we prefer what is represented by

Figure 2:

The key difference between the two graphs is that

Figure 2 accepts proportionality up to a certain point, after which each unit of severity of penalty diminishes with the unit of the seriousness of crime, never reaching some penalty, D (perhaps death).

A view reminiscent of the asymptotic view has been mentioned by Shelly Kagan in his magisterial

The Geometry of Desert. A large majority of that book uses algorithms and graphs to think about how much moral value is produced in lives when people are given (some of) what they deserve, which is distinct from the topic of this article, which is how to understand what counts as a deserved penalty in the first place. However, in the sixth chapter, Kagan does address the latter issue, and there he discusses the principle that ‘as your level of vice increases, still further increases in vice result in ever smaller reductions in absolute desert’ [

16] (p. 270).

There are some important differences between Kagan’s non-linear principle and ours that should be noted. One is that his principle indeed differs from the asymptotic principle. For example, the latter accepts proportionality, with non-linearity kicking in only at a certain late stage, whereas Kagan’s is non-linear through and through, with disproportionality entering in early on. For another example, the asymptotic principle is about how much punishment to impose for particular actions, and, so, it is potentially relevant to public policy in respect to sentencing criminals, whereas Kagan’s project is in the first instance about the desert of a person for vices and also virtues throughout his whole life, relevant particularly from a God’s-eye point of view.

For another kind of difference between our approaches, Kagan, in fact, favors proportionality and rejects the non-linear principle that he articulates as ‘unattractive’ and ‘implausible’ [

16] (pp. 271, 275). He is unable to see any motivation for it and provides an argument against it, which we address below when aiming to defend the asymptotic view. (The motivations for the asymptotic view that we advance in this article might provide some support for the principle that Kagan rejects, but the above differences would be important to keep in mind when trying to make the application.)

Principles akin to the asymptotic view have also been invoked in the context of multiple offenses, whether they are many done at the same time by a given offender or many done over time by him. Of particular interest, it has been suggested in the context of multiple offenses that ‘each new crime should contribute less to the overall punishment’ [

17] (p. 6).

However, the asymptotic view is meant to apply to single crimes, comparing deserved penalties for, say, assault and burglary (as above) and not merely to multiple crimes committed by the same person. Although we are naturally sympathetic to the idea of applying the asymptotic view to multiple crimes, that would involve complications that do not bear on the single case, which is our primary concern. For example, there is discussion of whether multiple sentences should be discounted by time intervals between crimes [

17] (p. 7), which obviously does not apply to the single case.

Both the (lower) range view and the asymptotic view of which penalty is deserved for a given crime broadly adhere to the backward-looking, ordinal principle that the worse the crime, the more severe the penalty should be. However, they also include cardinal tracking of a kind that we submit renders them good candidates for being accounts of how much punishment is deserved, despite not prescribing proportionality (even if essentially referring to it). If one is disinclined to call these accounts of ‘deserved punishment’, what is one to call them? If the reader elects to call them ‘the Metz views’, that would be fine with us, but they seem to us more aptly characterized as under-appreciated versions of the desert theory. Their articulation at least demonstrates that it is inappropriate to define the phrase ‘desert theory’ and cognate words (such as ‘retributivism’) in terms of proportionate sentences.

Return, now, to the four objections to the forward-looking theories, which are often taken to be positive support for proportionality. Proportionality, the range view, and the asymptotic view all comparably avoid and explain the force of these objections, so that the objections are plausibly viewed as supporting desert theory in general but not any particular version of it, such as proportionality. All three accounts of how much punishment is deserved clearly entail that it would be pro tanto unjust either to inflict a penalty on someone who has not culpably broken a just law or to acquit a person who has culpably broken a just law. In addition, all three accounts of how much punishment is deserved entail that it would be pro tanto unjust either to punish a trivial crime with a harsh penalty or to punish a serious crime with a light penalty.

To be sure, some adherents to a proportionality principle will criticize the non-proportionate alternatives for being unable to ground sufficiently harsh penalties. However, that point is not relevant at this point in the dialectic, which instead concerns the implications of standard objections to forward-looking theories, such as that these theories can incorrectly prescribe 20 years in prison for failing to indicate when switching lanes and a small fine for murder. Proportionality, the range view, and the asymptotic view all avoid entailing that such penalties are just, and they also provide plausible explanations of why they would be unjust. Proportionality gains no unique support from the stock reasons to reject forward-looking theories; the range view and asymptotic view receive comparable support. It is reasonable to suppose that, in order to avoid the objections to forward-looking theories, there must be reference to and even alignment with proportionality, but what the range and asymptotic views reveal is that it is not necessary for prescribed penalties to be proportionate.

4. Advantages of Non-Proportionate Desert

In the previous section, we articulated two non-proportionate conceptions of how much punishment is deserved and began to argue in favor of them by showing that they receive no less support from the reasons to reject forward-looking theories than the standard, proportionality principle does. In this section, we provide additional argumentation in favor of the non-proportionate approaches, by showing that they avoid three problems facing proportionality. One of the problems with proportionality is familiar, with us indicating how our non-proportionality can avoid it, but the other two problems are, for all we know, new.

4.1. Impossible Penalties

Our first objection to proportionality is one that we have not encountered before in the literature. It is that if desert is to ground justice, then it must be physically possible to impose deserved penalties but that, in some cases, it is impossible for us to mete out proportionate penalties. This objection does not depend on the lex talionis variant, as one might have supposed. Instead, working squarely with W × C = P, we note that some proportionate penalties are beyond human powers to impose, making proportionality an implausible ground of just institutions. Some people commit crimes on such a massive scale that they would not live long enough for us to give them a proportionate response.

Consider, for instance, a person responsible for an act that is intended to cause, and indeed succeeds in causing, the deaths of tens of thousands of other people. On a straightforward understanding of proportionality, simply executing this person would be disproportionately light. Even subjecting the person to torturous conditions for the rest of his life, making his fate worse than death, would be disproportionately light, at least if this person had himself caused substantial misery to those tens of thousands in the run up to having them killed.

Supposing that justice prescribes reasons for action to us and supposing reasons for action imply that agents can do what they ought to do, a just penalty is one that is possible for us to carry out. However, it is not possible for us to mete out proportionate penalties in response to certain crimes, meaning that such penalties are not just. If desert is going to ground justice of the sort that human beings institutionally enforce, then we must be able to distribute the penalties that desert prescribes. However, in some cases, we simply

cannot treat a person ‘

as badly….as he himself chooses to treat others’ [

18] (p. 140).

In reply, one might suggest that this is an instance of multiple offenses, and so it is not of much relevance. Perhaps it is a case of thousands of murders. However, we point out that there is a single act involved, such as the detonation of a bomb, and that the natural way to describe the case is as a ‘crime against humanity’ (not ‘crimes against human beings’). Simply having negative effects on lots of people does not in itself mean that there are multiple crimes. Counterfeiting, for example, exploits everyone who uses the money, but surely the right charge would be a single crime (at least if done on one occasion).

It is open to the friend of proportionality to maintain that it would be good for an offender to receive a certain severe punishment that we cannot impose (cf. [

16]), but that is different from the claim that we

should give it to him, where justice is commonly taken to ground prescriptions for action and not mere value judgments. In addition, it is open to the friend of proportionality to maintain that it would be

just for God to give an offender certain severe punishment, but we presume that desert theory is being advocated to serve as a guide, not for an inhuman agent such as a perfect being, but rather for a state’s sentencing policy.

Although the range view can avoid this objection to a large extent, we accept that there are likely going to be some extreme cases where even halving the proportionate penalty would still constitute a punishment too great for humans to be able to impose. In contrast, we suspect the asymptotic view in principle can neatly avoid the objection. If after, say, the penalty for a severe beating, penalties increased, but only marginally (and also to an even lesser extent) for each additional serious crime, then judges in principle could always mete out just deserts to human beings.

4.2. Forbidden Penalties

Whereas the first objection to proportionality is that it prescribes some penalties that only God could impose (or at least that we could not), the second is that it prescribes some penalties that are in one’s power to mete out but that would be intuitively unjust. This second objection is common to encounter in the literature. It is said that some proportionate penalties are ‘barbaric’, ‘uncivilized’, ‘inhumane’, and the like. Here, one

could treat a person ‘

as badly….as he himself chooses to treat others’ [

18] (p. 140), but one

should not, as it would do him an injustice.

There are some adherents to proportionality who bite the bullet by accepting that the state ought to be in the business of meting out exceptionally harsh treatment [

8] (esp. pp. 61–97), [

13]. Stephen Kershnar has done the most to support the view that the state should under certain conditions impose punishments such as ‘drilling in an unanesthetized tooth, branding with a hot iron, car-battery shocks to the genitalia, rape by dogs, anal penetration by toilet plungers, or jaw breaking by an expanding mechanical instrument’ [

19] (p. 60). Much of his reasoning over the years has turned on the idea that it is possible to waive one’s rights not to be treated in these ways that could be proportionate to one’s crimes, whether by virtue of forfeiting these rights upon having committed the crimes or making a free and informed choice to bear the treatment (say, in lieu of prison).

We do not use space here to rebut Kershnar’s position and other defenses of exceptionally harsh treatment, instead looking for a way to make good sense of deserved penalties for those who reject it. (At least one of us would appeal to a non-Kantian moral foundation, according to which a person has a dignity in virtue of her capacity, not to make autonomous choices, but rather to be party to harmonious relationships that include care for others’ good. The relational ethic forbids agents from attending merely to people’s decisions when determining whether to impose harms on them; respect requires consideration of their good, too. See [

20] (pp. 186–188).) We have (in

Section 3) noted that one strategy is unavailable, which is that of invoking a merely ordinal scale, according to which the worse the crime, the harsher the penalty should be, without requiring any sort of cardinal comparability between the crime and the penalty. The (lower) range view is more plausibly viewed as an instance of desert theory while also doing a reasonable job of avoiding the prescription of exceptionally harsh treatment. If a penalty for murder must be halved, for instance, then

often the (lower) range view will not prescribe something as harsh as murder.

However, there will be extreme cases, of a crime against humanity, in which even halving the proportionate penalty would be extremely severe. We therefore ultimately think that the asymptotic view is essential to avoid the concern fully, supposing, of course, that the point at which diminishing marginal penalties for crimes kicks in is one that is not extremely harsh (on which one can see

Section 5 below).

4.3. Coherence with Positive Desert

A third reason to favor the non-proportionate accounts of how much punishment is deserved relative to proportionality is that proportionality does not fit (so to speak) intuitions about key cases of positive desert. To be sure, an ordinal principle broadly holds for positive desert, such that, roughly speaking, those who are more positively deserving deserve more good. However, proportionality strikes us as a poor candidate for how to mete out positive desert, a point we do not think has been adequately appreciated.

For an initial example, when we consider how much praise or reward we ought to give to heroes who have risked life and limb to save those of others, it would be unusual to insist that someone who rescued five people from a burning building should receive a quarter more of what is desirable relative to someone who rescued four people. Something like the range view would make good sense of why non-proportionality is not merely permissible but also deserved. According to it, two people who have made different degrees of contributions could deserve the same reward, due to overlap in the ranges. For instance, if intentionally saving five people is worth 500 while saving four is 400, then, applying the discount formula above from the context of negative desert (we note that different discount formulas might be apt for different desert contexts, but lack any account of how to specify them, with one point of this article instead being that developing one would be a worthwhile project), one would conclude that the former should receive a reward between 375–250, while the latter should receive a reward between 300–200.

For another example, think about how much to pay someone for her labor on the job, a context in which talk of ‘proportionality’ and the like is admittedly more common than in that of heroism. For instance, one encounters the claim that, as a matter of ‘just deserts’, ‘I should focus not on the marginal utility of different individuals but on the congruence between their contributions and their compensation’ [

21] (p. 295); see also [

22]. Here, too, though, we deny that proportionality is intuitively required for a desert. Using a case similar to the above, does a nurse who has over the course of a year saved five lives that are worth living necessarily deserve a quarter more financial compensation than a nurse who has saved only four? We think not, with the range view providing a plausible explanation of why. (Here, we appeal to ‘objective’ contributions to people’s quality of life as opposed to the ‘subjective’ satisfaction of demand on a market. We simply do not think that those who sell cigarettes or gadgets planned to become obsolete deserve their riches.)

Furthermore, many desert theorists and others are drawn toward what is these days sometimes called ‘limitarianism’ [

23], according to which there should be an upper limit on the amount of wealth one should receive. Intuitively, no one

deserves to be a billionaire. Of course, that might be because billions of dollars are not proportionate to the degree to which any human being has contributed to the well-being of others or even could (on which one can see [

24] (p. 2)). However, the asymptotic view also provides a plausible explanation of what is wrong with extreme concentrations of wealth, for, according to it, at a certain level of positive desert, the financial reward for each additional unit of contribution should diminish toward zero.

Joel Feinberg suggests another desert-based principle of economic justice that includes proportionality, but it would apportion reward to sacrifice on the job, not to the contribution made [

25] (pp. 151–152). However, it is not clear that apportioning reward to sacrifice on the job is really a matter of desert so much as a compensation for harm, something T. M. Scanlon suggests [

26] (pp. 127–128). Furthermore, even if that is properly understood as a desert context, apportioning reward to contribution to society is more analogous to apportioning punishment to crime done to society.

We have been presuming here that negative desert is analogous to positive desert, an assumption that could be questioned. However, we submit that it is the burden of the interlocutor to provide a specific reason to doubt that they are relevantly similar, in the face of many other patent similarities. Desert in both negative and positive contexts characteristically involves all the following: a person’s will being exercised in either a desirable or undesirable way as the ‘desert-base’; a response of the same quality (roughly, harm for harm, benefit for benefit); a response that is gradational in quantity, such that the more of the desert base, the more that is deserved; and a substantial ‘backward-looking’ motivation, with the response being meted out because of the past exercise of the person’s will, not so much for prospective change on the part of her or others. In the face of these commonalities, we follow others (even if not many) who have thought it right to align negative and positive desert when formulating theories of them, e.g., [

7,

22].

5. Conclusions

We conclude this article by addressing an objection that friends of proportionality are sure to make to our proposal and by indicating some projects that merit being undertaken, supposing that it is nonetheless of interest. Although we ourselves are not desert theorists, the modifications we have proposed here make that framework somewhat more attractive to us and hence inclined to put more thought into it.

The natural objection that is surely to come from adherents to the standard view of deserved penalties is that the ones prescribed by the (lower) range view, if not also the asymptotic view, are intuitively too light. With regard to the range view, halving the proportionate penalty for someone guilty of murder will seem inadequate to some. Then, an implication of the asymptotic view is, as Kagan points out in respect to bad character (as opposed to wrong acts, on which we have focused here), that ‘increased vice results in ever smaller reductions in absolute desert’ such that ‘eventually, even massive increases in vice will result in only negligible reductions in what is deserved’ [

16] (p. 271).

However, some departure from proportionality is essential, if we are going to avoid the concerns about exceptionally harsh treatments that are either impossible or forbidden for human persons to mete out. One option for the desert theorist would be to advance a hybrid account, according to which desert is one principle that is to be balanced with, and often constrained by, some other principle(s). However, we have sought to provide interpretations of deserved penalties that do not invoke additional principles, that avoid prescribing exceptionally harsh treatments, and that are independently well motivated. We therefore think desert theorists should work with our approaches, at least insofar as they want to prescribe a system of penalties that are workable and intuitively appropriate for a state. We submit that any other invocation of desert would consist either of a cosmic conception of justice, i.e., for God to apportion, or of a mere intrinsic good that, say, karma could promote.

Going forward, if the (lower) range view is prima facie attractive, then there needs to be reflection on how to specify the discount by which proportionality is reduced. We have suggested a range of three-quarters to a half for the sake of illustration, but no more than that. One natural way to proceed would be to appeal to intuitions that are widely shared among desert theorists or policymakers in the many jurisdictions that clearly aim to base penalties in large part on the nature of the crime. If judgments align in respect to the amounts of harm or subordination that are deserved for a certain crime, such as hijacking, that is some evidence that they are indeed deserved for it. It is also worth considering whether ranges differ depending on desert contexts and what might explain that (supposing that it is not ‘institutional’ factors that do the work).

If the asymptotic view is prima facie attractive, then there needs to be reflection on how to specify the penalty at which proportionality becomes ‘too much’ and diminishing marginal harm/subordination for a crime should be deemed operative. Notice that the penalty cannot sensibly be one that is in fact inhumane or even just below what is inhumane, since the asymptotic view allows for indefinite increases in penalties (even if, at a certain point, each one must be less than the one for the previous unit), such that those who commit crimes against humanity might end up deserving inhumane penalties. Instead, if a judgment of what is inhumane is going to enter in, then it must be to specify the highest penalty a human being could deserve from the state, entailing that the point at which non-linearity kicks in is for some crime noticeably below that.

It might seem that by appealing to what is inhumane (or barbaric or uncivilized, etc.), we are appealing to a principle external to desert theory, something that we just suggested above we have striven to avoid. However, there is a difference between appealing to what is inhumane in order to specify what is deserved, on the one hand, and appealing to what is inhumane in order to place limits on the meting out of what is deserved, on the other. We are advocating for the former, which we find plausible, since we doubt that desert is foundational (even if we also doubt that it is a function of convention and crime control à la von Hirsch above). Supposing that giving people what they deserve is one way, say, to treat persons with respect, then it would be natural for broader considerations of respect to inform, as opposed to constrain, our understandings of what is deserved.