1. Introduction

“Wisdom is of the soul, Is not susceptible of proof, Is its own proof.”

There is an important distinction to be made between knowing something and, more simply, knowing about that thing—the difference involving both ‘experience’ and ‘skill’, two attributes essential to the former but unnecessary regarding the latter. For example, people tend to know about clay, what it is, but only an expert potter, from experience and skill acquired through learning about and actually working it, can properly be said to ‘know’ clay and so be able to use it like living matter, as an extension of the personality, to create a distinctive object—a simple bowl perhaps, both utilitarian and beautiful.

Bearing this in mind, consider Beatrice and Benedick, the characters in Shakespeare’s play, Much Ado about Nothing, who seem initially to harbor a degree of indifference approaching antipathy towards one other, the two nevertheless being revealed eventually as a perfectly matched couple. So might it be with the academic disciplines of philosophy and psychology, should they come not only to teach about their respective subjects but also to educate students to become fully knowledgeable, skilled and experienced in their particular arts, preparing them to become citizens, making full and generous individual and collective contributions towards a safe, harmonious and healthy society. In this regard, the proposal suggested by this paper is born of the conviction that, with such a fruitful aim, the two disciplines have much to offer one another, giving rise to the possibility of future cohorts of experienced psychologically-minded philosophers and skillful philosophically-minded psychologists, pioneers set to influence a wider culture and future generations of health and social care professionals, schoolteachers, and leaders throughout the world in other spheres of activity—political, religious, commercial, artistic and military included [

2].

2. Developmental Psychology

Although numerous branches of human psychology are relevant—notable among them ‘positive psychology [

3]—the most persuasive regarding this proposal for psycho-philosophical engagement is the field of that aspect of psychology known as ‘developmental psychology’. The health of any living organism demands more than general well-being; it also implies a pattern of growth and evolution in the direction of becoming a functioning whole, both intrinsically and in relation to its surroundings, in relation in particular to other living creatures with which it is or may be in contact and communication through a shared habitat or environment.

Seventy years ago, Erik Erikson (1902–1994) made clear that developmental psychology is in essence about the healthy growth of individual people towards a consistent sense of identity and resilient personal integrity, characterized by notions of maturity and wisdom, enabling fruitful and harmonious interactions with others and positive, fulfilling and meaningful engagement at the levels of both local community and global society [

4,

5]. According to Erikson, the stage or ‘crisis’ of identity arrives with adolescence. As educated school leavers prepare for young adulthood and its many associated challenges, faced with choices regarding further study, it is gratifying yet not surprising that they are attracted to university courses in both psychology and philosophy. If Erikson is right, these young people naturally want to find out about themselves, about each other, and about people in general in order to prepare for a fulfilling and meaningful life. Arguably, however, the courses in these disciplines hitherto on offer for undergraduates fall short of providing what they desire and truly need in this regard.

The concept of ‘wisdom’ in this context not only provides a useful bridge between the disciplines of psychology and philosophy, but may also be invoked to ensure that they each avoid the pitfall of becoming ‘academic’ only in the sense of being “abstract, merely theoretical, or, unpractical” [

6] (p. 11). In his book ‘Philosophy as a Way of Life’, reappraising what it means to engage in his subject, philosophy professor Pierre Hadot (1922–2010) using inclusive language, wrote, “A philo-sopher is in love with wisdom… He knows that the normal natural state of men should be wisdom, for wisdom is nothing more than the vision of things as they are, the vision of the cosmos as it is in the light of reason, and wisdom is also nothing more than the mode of being and living that should correspond to this vision” [

7] (pp. 57–59). For clarification, Hadot also wrote, “In antiquity, the philosopher regards himself as a philosopher, not because he develops a philosophical discourse, but because he lives philosophically” [

7] (p. 27), which is to say ever-increasingly wisely.

How might this join philosophy and psychology together? As Hadot puts it, “All (Hellenic) schools believed in the freedom of the will, thanks to which man has the possibility to modify, improve, and realize himself” [

7] (p. 102). Teachers of philosophy will be better placed to address the needs of students then by paying earnest attention to the findings of developmental psychology. Teachers of psychology will likewise do well to bear constantly in mind that their students represent examples of people undergoing such development. It would therefore seem that both sets of teachers have a responsibility to ensure that their courses genuinely foster growth towards wisdom. Neither, in this regard, as dedicated mentors, teaching by both precept and example, will wise educators neglect to give priority, time and close attention to their own personal development. How may growth towards wisdom be encouraged? As will be discussed later, and in keeping with earlier statements, it will depend on gaining experience and developing skills, more therefore on practice than intellect. Equally, it will involve ‘education’, on teachers ‘leading out’ from within their charges the wisdom that sages have described through the ages as innate and ultimately accessible to all.

Wisdom

What is wisdom? In response to this question, it helps to distinguish between two complementary kinds of knowledge under separate headings: science and wisdom. To put it simply for orientation purposes, science is the knowledge of facts; of things, and how they work. Wisdom, qualitatively different, is the knowledge of how to live well—both for yourself and other people. The meaning of the word ‘wisdom’ is likely to become clearer the wiser a person becomes, reaching towards a high degree of psychological maturity and integrity, in ways to be explained later. However, a provisional, working definition is offered for the purposes of this paper:

“Wisdom is the knowledge of how to be and behave for the best, for all concerned, in any given situation”

Unlike the knowledge of well-established facts, wisdom varies; what works in one situation, at this particular time, and for one person, may fail in other circumstances, at a different time, or for another person. Additionally, rather than being deduced using the methods of science—that is by reasoned, binary thinking about a necessarily fragmented appreciation of circumstances obtained through the senses, often involving the use of measuring instruments—wisdom can be described as holistic, intuitive, and immeasurable, grasping the matter in hand unerringly in the full context and immensity of the whole. An incontrovertible form of knowledge, wisdom may thus be considered sacred, therefore both powerful and inviolable, beyond personal opinions and preferences. The search for wisdom is about a person—and, collectively, a community or society—ever growing in psychological maturity, thus becoming increasingly experienced in life’s problems and how most skillfully to resolve them. For budding psychologists and philosophers to make progress in that regard, some form of deeply personal search seems a primary necessity. Guidance will obviously be helpful.

Several thinkers have provided useful outlines, models, maps, or guides to this maturation process by devising developmental schemes or systems. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987), for example, outlined a course towards moral maturity describing three levels of moral development, with two stages at each level. To give an idea of the range, Stage 1 (Level 1a) is driven by obedience and punishment-avoidance. According to this, actions are considered by young children as wrong if they are punished, not otherwise. The more severe the punishment, the worse the child considers the act to be. By contrast, Kohlberg’s Stage 5 (Level 3a) recognizes that people come to hold different opinions and values, requiring moral dilemmas to be resolved according to majority decisions and compromise. Stage 6 (Level 3b) goes even further, and depends on abstract reasoning about what is right, considering ethical problems in terms of justice rather than law. The role of consensus may also be challenged. An individual who has reached Kohlberg’s Stage 6 may feel bound to act in a certain way, even against the decisions of others, guided by some inner moral compass, true self, or soul [

9].

Erikson’s plan, already mentioned, involves a ‘life cycle’ of eight stages, each a ‘crisis’ resulting in a balance between favorable and unfavorable outcomes, each stage preparing a person cumulatively for the next. Carl Jung (1875–1961) referred to the same process as ‘individuation’, according to which the ego—the knowing, willing ‘I’, the center of consciousness [

10] (p. 21)—makes use of a public mask or persona that shields the individual from conscious awareness of that which it does not like or deems socially unacceptable. This material, threatening unwanted and uncomfortable thoughts, emotions and impulses, Jung refers to collectively as the personal unconscious or shadow.

In the early stages of individuation, the shadow aspects are often ‘projected’ outwards, people see and experience falsely or exaggerated in others, ideas, attitudes and behaviors that they have difficulty tolerating in themselves, hence the biblical recommendation to, “First take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbour’s eye” [

11] (p. 6). With maturity, the shadow is re-integrated, as the ego—communicating with and increasingly influenced by what Jung calls archetypes of the collective unconscious—evolves into the self. Of the latter, Frieda Fordham writes, “The term ‘self’ is not used by Jung as in everyday speech, but in the Eastern manner… In Hindu thought the self is the supreme principle, the supreme oneness of being” [

10] (p. 62, footnote 1). Jung’s ‘self’ may thus be compared with a person’s ‘wisdom mind’, their ‘true’, ‘higher’, or ‘spiritual’ self, and equates for many with the idea of a human ‘soul’.

3. Dimensions of Human Experience and Understanding

Jung does not hesitate to link personal growth towards wisdom and maturity with a spiritual dimension. But a question immediately arises: a spiritual dimension of what? Before returning to a discussion of developmental psychology, a brief digression is required.

For Jung, or any author, to express ideas about a spiritual dimension of ‘existence’ or of ‘reality’ presents difficulties of interpretation and provides troublesome grounds for disagreement. Less contentious, however, is the idea of a spiritual dimension of ‘human experience and understanding’. Those who claim no experiences of a spiritual nature, and who may therefore feel uncomfortable with the notion of a spiritual dimension, will nevertheless be obliged to admit that some credible experiences described by other people -characterized, for example, by a sense of wonder and cosmic wholeness—could usefully be categorized, at least provisionally, as ‘spiritual’ or perhaps ‘holistic’.

This will make more sense when the spiritual dimension is described as seamlessly inter-connected with four co-terminous similarly linked and overlapping others, to encapsulate the entirety of human experience and understanding. These other four dimensions are: physical (concerning energy and matter), biological (organs and organisms), psychological (mental activity), and social (relationships and communities). Any aspect of human existence—including the entire plethora of subjects addressed by science—may wisely be investigated and understood through the binocular lenses associated with all five dimensions—the twin lenses, that is, firstly of personal subjective experience and secondly of shared understanding.

Health, for example, is a concept etymologically linked to wholeness, such that ‘healing’ essentially means ‘to make whole’, and can be regarded in terms of bodily (physical, biological), mental (psychological), communal (social) and holistic (spiritual) health, an idea that is reflected in the so-called ‘bio-psycho-socio-spiritual’ formulations of mental disorder recommended in contemporary psychiatric practice [

12] (p. 32) The importance of the spiritual dimension to mental health has been recognized, for example, by the formation in 1999 of the influential ‘Spirituality and Psychiatry’ special interest group of the UK’s Royal College of Psychiatrists, of which there are now over 3000 psychiatrist members. According to the special interest group website, “Spirituality can be as broad as the essentially human, personal and interpersonal dimension, which integrates and transcends the cultural, religious, psychological, social and emotional aspects of the person, or more specifically concerned with ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’. Spirituality is a universal human quality that every person can experience independently of religion. It therefore brings together all those involved in mental health care, regardless of creed or culture” [

13].

There is a paradox regarding health, for it is possible to be unwell either physically, psychologically, or both, while remaining spiritually healthy. Indeed, ‘post-traumatic growth’ [

14]—according to which a person achieves renewed inner harmony and expanded horizons, while undergoing spontaneous revision of former tendencies towards self-seeking and self-indulgent values, ambitions and priorities—may be triggered by an episode of serious illness like cancer [

15], or be associated with a period of mental instability indistinguishable from a bout of psychosis [

16].

The first four dimensions form the province of the natural and social sciences, amenable to examination through scientific methods of sense-based observation and verification, with results of investigations presented on the balance of statistical probabilities. However convincing the evidence may be, scientific knowledge is always open to the correction of new observations and experiences. A kind of uncertainty principle must be presumed always to apply. In his book ‘The Logos of the Soul’, the Jungian analytical psychologist and psychotherapist, Evangelos Christou (1922–1956), for example, has written that scientists, “Are never observing an objective event but only an objective event insofar as it has been modified by experimental interference and subjective presuppositions… The world is never seen as what it is but only as what it becomes once we decide to observe it and hence modify it”. “If these conditions are true for microphysics”, he adds rhetorically, “How true they must (also) be in the sciences of biology and psychology” [

17] (p. 38).

Thus, at each level, an unexplained element, a degree of mystery, necessarily remains. It may seem to some like heresy to say so, but science has no absolute knowledge. There is no certainty, for example, about the primal genesis of energy and matter, the origin of the physical dimension of the universe. Scientists can offer only theories and speculation regarding conditions contributing to the singularity of time and space that gave rise to what is referred to as the ‘big bang’. Similarly, theories and speculations about the biological dimension, about the origin of living organisms, of life in the universe, cannot hitherto be substantiated, only noted, accepted provisionally and investigated further. Such assumptions as are currently held, those which form the very basis of science, are increasingly coming under scrutiny and question by scientists themselves [

18]. Among these are the 90 advisers, representing 30 universities worldwide involved with the Galileo Commission, which has as its remit, “ To open public discourse and to find ways to expand science so that it can accommodate and explore important human experiences and questions that science, in its present form, is unable to integrate” [

19].

The called-for paradigm shift has already begun. Regarding perhaps the most central and vital aspect of the psychological dimension, human consciousness, for example, points 2, 3 and 4 of the Galileo Commission’s 14-point ‘Summary of Argument’ state: “The prevalent underlying assumptions, or world model, of the majority of modern scientists are narrowly naturalist in metaphysics, materialist in ontology and reductionist-empiricist in methodology. This results in the belief that consciousness is nothing but a consequence of complex arrangement of matter, or an emergent phenomenon of brain activity. This belief is neither proven, nor warranted” [

19].

A way forward, both conceptually, and practically in terms of methods of investigation, involves the completion of the dimensional scheme by a fifth, hierarchically superior, ‘spiritual’ or ‘holistic’ dimension, which many champion as an originating principle, seamlessly creating, linking and shaping the other four. Following a different logic, this dimension requires alternative, complementary methods of enquiry and verification to ascertain whether it truly and usefully reflects an aspect of human existence or ‘reality’. These methods come under the heading of spiritual exercises or wisdom practices and necessitate the acquisition of certain associated ‘holistic’ or ‘spiritual’ skills.

On this basis, the search for and attainment of wisdom can be considered in terms of developing an improving degree of spiritual awareness, which has nothing necessarily to do with religious beliefs or practices. This idea is further validated by Hadot’s descriptions of ancient Hellenic philosophy where, regarding methods of self-improvement, he writes, “Above all, every school practices exercises designed to ensure spiritual progress toward the ideal state of wisdom” [

7] (p. 59). Echoing Jung’s notion of ‘self’, Hadot elaborates as follows, “All spiritual exercises are, fundamentally, a return to the self, in which the self is liberated from the state of alienation into which it has been plunged by worries, passions and desires… With the help of these exercises, we should be able to attain to wisdom.” [

7] (p. 103).

Hadot adds, furthermore, that, “The practice of spiritual exercises implied a complete reversal of received ideas: one was to renounce the false values of wealth, honors, and pleasures, and turn towards the true values of virtue, contemplation, a simple life-style, and the simple happiness of existing” [

7] (p. 104).

Explaining his chosen term, Hadot wrote, “The word ‘spiritual’ is quite apt to make us understand that these exercises are the result, not merely of thought, but of the individual’s entire psychism (i.e., psycho-spiritual existence). Above all, the word ‘spiritual’ reveals the true dimensions of these exercises. By means of them, the individual raises himself up to the life of the objective Spirit; that is to say, he re-places himself within the perspective of the Whole” [

7] (p. 82). Time-honored, not only by ancient Greek philosophers but also by mystics and sages of all faith traditions, Eastern and Western, consideration of these exercises will nevertheless benefit from being updated in order to find greater acceptance in the relatively secular climate of contemporary world culture.

Christou has also contributed to the discussion about experience, as follows: “The difference between a thinking automat or a photographic plate and a human being remains that indefinable something we call soul; this would mean that a human being is able to experience what he thinks or feels, where the concept ‘experience’ means more than just perceive or think the content in question” [

17] (p. 23). He argued that the spiritual dimension is important not merely to investigate intellectually, but to experience through one’s spiritual self or soul, because, as he cautioned before his unfortunate early death, this dimension can no longer be safely excluded from consideration, either by scientists (including social scientists, therefore psychologists) or by philosophers: “Refusal to confront reality for what it is comes often from the trust in science to heal all ills and to bring about a human Utopia on this earth… On the contrary, it is now clear that this attitude has led us to the possibilities of complete and horrific self-destruction” [

17] (p. 22). Fortunately, this stark warning (issued in the 1950s with particular regard to thermo-nuclear weapons) is tempered by Christou’s more hopeful remark concerning a pathway of recovery: “The human personality… (contains) within itself the principle of its unification and the meaning of its life and its redemption” [

17] (p. 25). Further consideration of developmental psychology and wisdom practices will show how this principle of unification may fruitfully become manifest in a person’s life to everybody’s advantage.

4. The Path to Wisdom: Stages of Spiritual Development

Psychology professor, A Reza Arasteh (1927–1992), grounded in Western psychology, yet also influenced by the Sufism of his native cultural background and other Eastern religious traditions (but without referring specifically to spirituality or a spiritual dimension), published his masterly book, ‘Toward Final Personality Integration’, in 1975 [

20]. In an earlier paper, based on subjective personal experience that he called ‘visionary’, on objectivization of that experience, on clinical case studies from two cultures, and an analysis of final integration in autonomous individuals, Arasteh developed a universal theory of personality development, an integrated theory taking into account a universal understanding of both humankind and culture. He described final integration as, “A universal state regardless of time, place and the degree of culture”, adding, “The fully integrated person… becomes aware of the duality of thinking: that which is made by the mind and that which is achieved by sudden awareness, insight and intuition”. As a result, “Behavior becomes spontaneous”, and, “The function of insight-sudden awareness-is rooted in the creative force which man’s essence shares with the cosmic essence… Like flashes of lightning a succession of insights illuminates one’s mind and increases one’s vision… It is through these intuitive flashes that separation of subject and object ceases to exist” [

21] (pp. 61–73).

Those either skeptical of, or unduly daunted by, such descriptions of the goal of human psychological development can be reassured that attainment of highly advanced personal and spiritual maturity is relatively rare among the current world population, and usually develops gradually in stages. It often takes the greater part of a lifetime—or many lifetimes according to some traditions—to acquire the necessary experience and develop the requisite skills to enter the final phase. These points, however, present no effective argument against anyone setting out to make a sincere attempt at progress on the path towards wisdom. They do, though, indicate a need for commitment, patience and perseverance.

Arasteh’s description is consistent with similar accounts of the final stage in other schemes of developmental psychology that culminate in ‘individuation’, or ‘self-actualization’, the latter term being introduced by Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) as part of his influential theory of human motivation, at the pinnacle of what he refers to as a ‘hierarchy of needs’ [

22]. These various approaches are presented in the main wearing scientific, therefore secular, garb. Without neglecting the invaluable early contribution of William James (1842–1910) [

23], it was psychologist James Fowler (1940–2015), with the publication of his book Stages of Faith [

24], who first presented a developmental scheme centered firmly on the spiritual dimension.

Drawing on the work of Jean Piaget (1896–1980) focused on cognitive development [

25], Erikson’s life cycle studies, and Kohlberg’s contribution on moral development, based primarily on semi-structured interviews with over 600 people, Fowler outlined six stages of human development. Following infancy and a period of what he called ‘undifferentiated faith’, Fowler’s stages in sequence are called: 1. intuitive-projective, 2. mythic-literal, 3. synthetic-conventional, 4. individuative-reflective, 5. conjunctive, and 6. universalizing. Underlying his scheme was Fowler’s conviction that faith, not always religious in its content or context, is a universal feature of human living, an orientation of the total person, giving purpose and goal to one’s hopes and strivings, thoughts and actions. “Faith”, wrote Fowler, “Is a way of finding coherence in and giving meaning to the multiple forces and relations that make up our lives. Faith is a person’s way of seeing him- or herself in relation to others against a background of shared meaning and purpose” [

24] (p. 4).

The universalizing stage, corresponding to Arasteh’s final personality integration, is the least developed in Fowler’s scheme, partly because only one person (0.3% of the total sample) was deemed to have reached it, and Fowler was obliged to resort to considering public representatives embodying Stage 6 qualities in order to illustrate them. In describing people he calls ‘Universalizers’, he wrote, “Their felt sense of an ultimate environment is inclusive of all being. They have become incarnators and actualizers of the spirit of an inclusive and fulfilled human community. They are ‘contagious’ in the sense that they create zones of liberation from the social, political, economic and ideological shackles we place and endure on human futurity. Living with felt participation in a power that unifies and transforms the world, Universalizers are often experienced as subversive of the structures (including religious structures) by which we sustain our individual and corporate survival, security and significance” [

25] (pp. 200–201). As a result, Fowler suggests, such people are often killed, that is martyred, a fate attributable to possibly five of his seven listed exemplars, Gandhi, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King Jr., Dag Hammarskjold, and Thomas Merton, although the deaths of the last two have been reported officially so far as due to unfortunate accidents [

26].

But there are different ways of laying down one’s life for others, through lifelong service, for example. Fowler describes people in Stage 6 as, “Having a special grace that makes them seem more lucid, simpler, and yet somehow more fully human than the rest of us. Their community is universal in extent... Life is both loved and held loosely. Such persons are ready for fellowship with persons at any of the other stages and from any other faith tradition” [

25] (p. 201). They are humble, do not draw attention to themselves or their actions on behalf of others, and so slip easily below the radar. Their selfless contributions are often unrecognized and therefore under-reported.

To restore balance and include such people, also to enhance Fowler’s scheme in certain ways, the present author has revised it, renaming the six stages while taking particular care to examine the psychological processes involved in making progress from one stage to the next, and clarifying the different tasks, attitudes and priorities at each stage [

27]. The authority attributable to this revised scheme is derived from shared human experience of the following six recognizable (re-named) stages that follow infancy, presented here with a brief description in each case:

Egocentric (immature, self-referenced existence);

Conditioning (learning by absorption from strong family, communal and cultural traditions);

Conformist (seeking to belong, either coerced or choosing freely to follow social trends and conventions);

Individual (choosing, in preference, to think, speak and act independently);

Integration (shifting values and behavior towards altruism, through recognizing one’s deep kinship with fellow human beings, with nature and everything else, mediated through a growing intuition regarding a cosmic spirit or life-force, the sacred unity of existence, or divine purpose);

Universal (achieving an advanced state of maturity and wisdom, becoming a natural teacher and compassionate healer of the broken bodies, minds and spirits of other people, and of society at large).

The changing priorities, attitudes and tasks at each stage can be broadly and briefly summarized as follows [

27] (pp. 34–37):

In Stage 1, attitudes and priorities are concerned with safety, survival and comfort, seeking to fulfil natural likes and dislikes, with limited recognition of differences between spiritual (or ‘cosmic’) and everyday awareness.

Stage 2 involves learning about the world in general, and especially about traditions, rules and conventions, with diminishing attention to spiritual awareness as time passes. It is a stage during which a culturally determined, secular, scientific, materialist worldview tends to emerge as dominant.

In Stage 3, strong attachments and aversions are made and consolidated, reflecting a natural desire to further one’s ambitions towards personal gratification and social integration. This is achieved through acquisition of prized allegiances, status and possessions, and the denial or rejection of whatever seems uncomfortable, alien and contradictory.

In Stage 4, priorities involve discovering, accepting and developing oneself as an independent and responsible observer-participant in one’s own life, relinquishing some former attachments and adjusting to the resulting uncertainty and relative isolation. Strong self-interest gradually weakens but is not yet fully relinquished.

In Stage 5, the emphasis shifts towards re-evaluation of one’s priorities, values and behavior from a universal perspective, loosening the strength of former attachments and aversions, shedding partisan adherences, bringing one’s life increasingly into line with the highest altruistic ideals devoted to the service of others.

In Stage 6, compassion, humility, patience and other beneficial attributes develop alongside, and contributing to, wisdom. Life’s intrinsic meaning is revealed, understood and fully accepted. Being, rather than doing or achieving, is given priority, with the result of living freely in the moment. This is a stage associated with neither anxiety over threats, nor fear at the prospect of further losses, not even the eventual loss of every material thing occasioned by death.

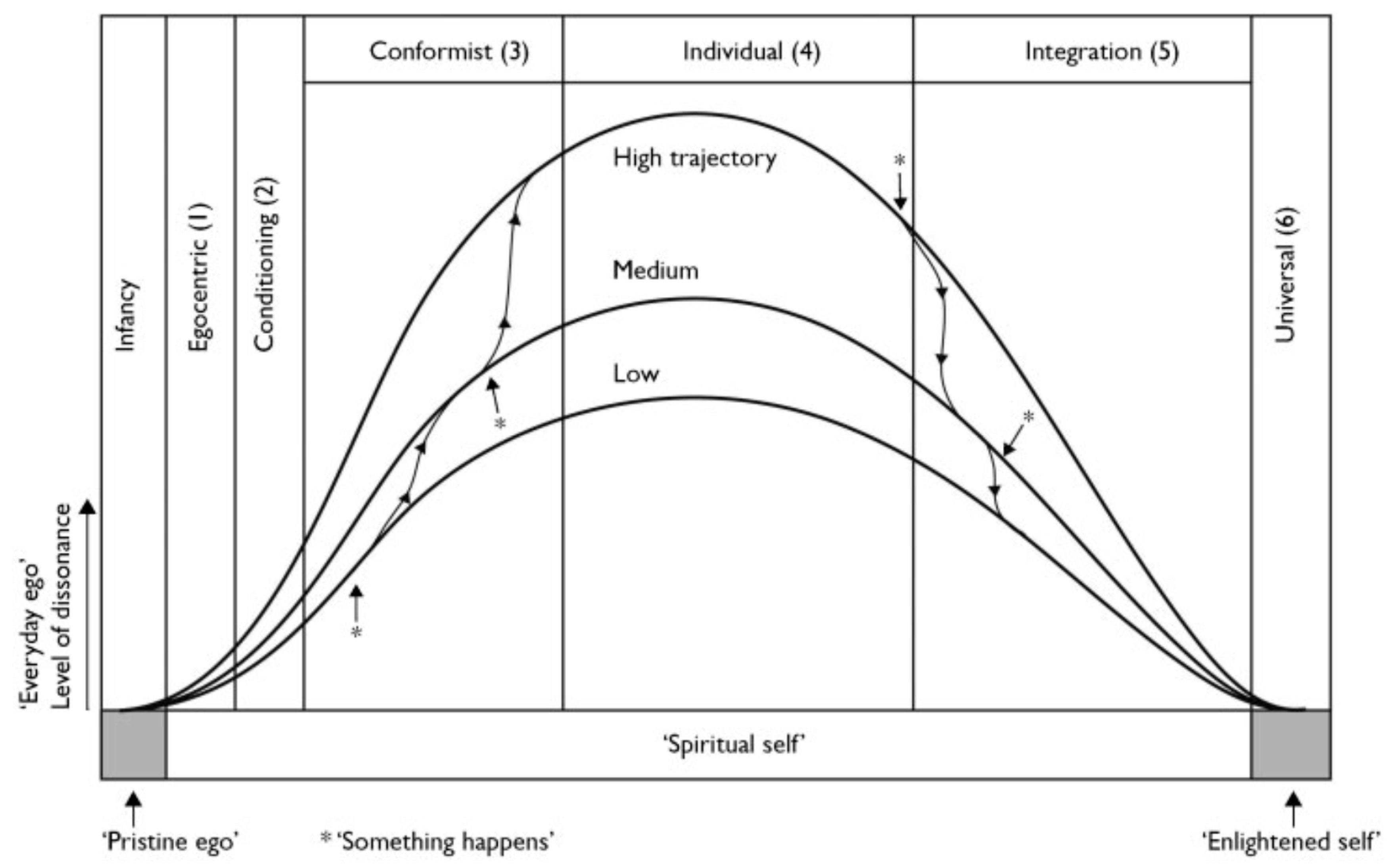

This scheme can be further elucidated by means of the so-called ‘meaning of life’ diagram (

Figure 1), which shows across the six stages the developmental path of the ‘everyday ego’ along three trajectories, first rising then falling, showing the split or dissonance between the ego and the constantly, if subliminally, present ‘spiritual self’.

The three trajectories, depicted stylistically here as high, medium and low, indicate that, as life proceeds, some people experience less inner psychological conflict than others, making progress and transition through the stages more smoothly, as indicated by the patterns of their life histories. Innate factors regarding temperament, together with aspects of personal conditioning through the family and social environment, determine the general trend for each individual. Life events and experiences play an important role, too, as the arrows in

Figure 1 indicate. Whenever ‘something happens’, resulting in some form of meaningful experience, something deeply significant and personal, a person may shift to greater or lesser degree from a lower towards a higher trajectory or vice versa. Spiritual exercises are effective by limiting increasing dissonance during the earlier stages, and by promoting progress towards re-integration of ego and self later.

5. Transition: Emotional Healing and Personal Growth

According to Fowler’s research, reinforced by general observation, most people from the teen years onwards occupy Conformist Stage 3, Individual Stage 4, or some halfway-house between the two. This situation is indicative of two powerful but contrasting drives: (i) to conform within family and society and (ii) to think, speak and act independently.

In Stage 3, people tend to adhere, whether rigidly or flexibly, to the culture, authority, values and belief systems (including religious/secular belief systems and political ideologies), also to the laws, customs, allegiances, rituals and other ingrained behavioral practices of the family, communal groups and society at large. There is comfort and safety in belonging, with the risk of being ostracized and ridiculed, and of feeling threatened when showing signs of being different. Nevertheless, horizons broaden during late adolescence; for example, on leaving home, perhaps taking a gap year, and when going to university; bringing new contact and eventual familiarity with different people, cultures, conventions, belief systems and so on. As a result, pressure grows to re-think priorities and take increasing responsibility for thoughts, feelings and intentions; for one’s words and actions; and, equally and importantly, for what one does not say and avoids doing.

This is to enter Stage 4, a key step towards personal maturity, but a stage in which—in a relatively immature, secular, materialist global culture, wherein goals of fame, wealth, property, possessions, position, and power over others are heavily, often subliminally, promoted—where people strive, aiming for success and to avoid failure, seeking to be winners rather than losers; sensitive guidance and enlightened leadership is required, essential not only for the well-being of such students and young people, but also more broadly for social health and equality, and for optimum husbandry of the planet.

Educational experiences are likely to play a significant part in this process. Transition from Stage 3 into Stage 4 is largely a matter of broadening one’s horizons, gaining knowledge, and increasing both one’s worldly and spiritual experiences of life, promoting an extensive review and revision of one’s previous allegiances, attachments and aversions. It becomes a period, often prolonged, of uncertainty, of shifting desires and antipathies, the formation and subsequent relinquishing of multiple new attachments and aversions, some fleeting, others more entrenched, arising in respect of people, places, possessions, activities, ideas and ideologies, dreams, expectations and more.

Desires and attachments throughout the life cycle instantly set up the psychological conditions for painful emotional responses to both threats and losses. However, comfort can be taken in that close examination of these conditions and their consequences reveals an agreeable logic to the processes of emotional healing and personal growth, as described by Whiteside [

29]. Both painful and pain-free emotions, such as those listed in

Table 1, are vital aspects of human experience, contributing significantly, moment by moment, day by day, to a person’s healthy sense of meaning and purpose, or its absence. In the development of wisdom, emotional sensitivity and self-awareness are of great value. The emotions are valuable indicators of spiritual experience, such as when people are, for example, ‘filled with awe and wonder’, ‘racked with tears and grief’, ‘paralyzed with fear’, ‘overflowing with a sense of peace and tranquility’, or ‘ecstatic with joy’. Understanding their logic helps the promotion of wisdom.

Table 1 offers a theoretical spectrum of eight pairs of painful and pain-free emotions, which appear as polar opposites but can also be understood paradoxically as complementary to one another. According to this scheme, for example, happiness is paired with its opposite, sadness; likewise, clarity with bewilderment. Each of the two members of each pair are fully inter-related and complement each other because, when one is present, by definition, the other is absent. Sometimes they alternate, often rapidly, and so appear to mingle; and any or all of the other eight pairs may be in play simultaneously. The following scheme may serve as a guide through, for example, a troubling episode of loss and grieving.

The dyads are referred to as ‘cognitive-emotional’ pairs to reflect that cognition (i.e., conscious reflection) is required to name the feeling sensations associated with each emotion. The ability to identify and name such feelings (lexithymia) is a skill beneficial to the pursuit of wisdom. The eight pairs form a spectrum of emotions, a basic palette for the playing out of desires and antipathies, responses to losses and threats. Thus, from the outset, not having what one desires occasions a measure of suffering. Equally, achieving one’s desire, securing an object of attachment (a person or possession, etc.) immediately sets up the condition of threat, the threat of absence, harm or damage, the threat therefore of some form of loss, response to which might involve the whole range of emotions.

To explain briefly, threats provoke the painful emotions of bewilderment, anxiety and doubt. Actual or imagined attacks (on one’s person, possessions, opinions or beliefs, for example) threaten impending loss and may provoke anger. Impending loss may also engender feelings of shame and guilt through feeling responsible for inadequate safeguarding. Actual and irretrievable losses give rise finally and naturally to sadness, allowing tension release (catharsis), for example through tears, allowing the cycles of emotional pain eventually to diminish.

Sadness therefore provides an important key to healthy grieving. It involves ‘letting go’, the freeing up and relinquishing of energy invested in attachments. The cleansing psychological effect of weeping, wailing and other accompaniments of grief, permit the loosening (‘lysis’) of emotional bonds to the object of loss, commencing the process of healing. As painful feelings lose energy, each is transformed into its pain-free complementary opposite. Bewilderment, anxiety and doubt shift towards clarity, calm and certainty. Anger diminishes into acceptance. Shame and guilt give way to purity, self-worth and innocence. Sadness is transformed into joy.

That wisdom may be approached through the pain of loss, that people grow through suffering rather than by avoiding it, is evidenced through the experience and understanding that calm, joy and acceptance are among the principle emotions and rewards of wisdom, which is characterized by greater degrees of equanimity and resilience than is usual during the earlier stages of personal development. It is noteworthy, too, that giving up the strong antipathy associated with powerfully entrenched aversions can also precipitate the cycle of emotional pain, to be followed eventually by relief and personal growth. This explains why tolerance and, especially, forgiveness are found to have such healing powers.

In Stages 3 and 4, it is entirely natural for people to resist change. Even the threat of change can arouse anger, an emotion which is often accompanied by a strong sense both of being right and of being ‘in the right’. This is destructive, and an ultimately self-destructive trap to avoid. Those who feel right, but are in fact mistaken about something, do well to pause before acting in anger. Those who are correct also do well to remain patient in the face of threats and challenges while anger subsides, remaining confident that their point of view will be upheld by events as they unfold, knowing too that a calmer frame of mind will be more persuasive than an aggressive one. The self-control required to pause and defer an emotion-driven response in such a situation represents another mark of wisdom.

Why does not all human emotional pain and suffering lead to personal growth? An answer to this question arises with the suggestion that nature provides a psychological mechanism for emotional healing comparable to the biological healing process of cuts and abrasions; and that, just as certain conditions must be met for flesh wounds to heal, so it is with emotional pain and trauma. Skin is weak and heals poorly in people who are undernourished, lacking essential proteins and vitamins. It is well known, too, that wounds do not heal if they are repetitive, extensive, badly soiled, or become infected. Doctors and nurses are obliged therefore to ensure the proper conditions for healing, through change of environment (hospitalization for example), with debridement and wound hygiene, by administering antiseptics and antibiotic medication, and also by applying sutures and bandaging. Nature can be relied upon to do the rest.

Emotional healing similarly proceeds best when certain advantageous conditions are met. It goes more smoothly when the affected person feels safe from further psychological threats and losses. Protection comes from feeling secure, valued and loved, from living in an environment of affection, trust and hope for the future. Healing is therefore promoted by healthy family relationships, and similarly by prevailing, conflict-free community and cultural interactions. In addition, emotional healing carries a valuable bonus because, as a direct natural consequence, personal growth is assured.

When the conditions for emotional healing are met, after successfully surviving and grieving a loss, people tend to become less regretful of what has happened in the past, less fearful of what might happen in the future, and less anxious concerning the present. They become more spontaneous, better able to live in the moment, better equipped to capture emerging opportunities; to engage anew with people and places, and with fresh activities; also better able to sit still and calmly appreciate beauty, to contemplate life’s path and ponder its values. In this way, experiencing and enduring suffering through to the culmination of the healing process contributes towards wisdom and personal maturity.

Throughout Stage 4 and well into Stage 5, people continue to experience attachments, desires and aversions, and so be susceptible to painful emotions like those listed. Nevertheless, experiencing and enduring adversity usually helps people develop increasing emotional resilience and stability, such that they grow incrementally wiser, calmer, happier, clearer in mind and more confident, while becoming less self-conscious, angry, guilty and ashamed. Losses, when encountered, are increasingly likely to result in the emotional release mechanism of wry, and later full-blown, humor, thus of laughter rather than tears. In addition, less frequently sorrowful, such people may nevertheless come to value tolerable sadness when it arises as a sign of growth; for example, when feeling sad in congruence with the misfortunes of others. Compare this also with the spontaneous experience of ‘sympathetic joy’, another marker of wisdom according to which a more mature person, rather than feeling envy, takes delight in the achievements and good fortune of others.

In addition, people who have satisfactorily weathered significant losses tend naturally to become more outward looking, increasingly aware of the plight and suffering of human beings everywhere who are all similarly susceptible to attachments, aversions, losses, accidents, injuries, mental afflictions, false expectations, ill health, ageing and death. Awakening to a new awareness that everyone suffers brings vital energy to one’s natural tendencies towards empathy and compassion, and this dawning insight ensures that people become increasingly unneighborly, more useful and valuable to others in their suffering. These are attributes particularly associated with Integration Stage 5.

6. Wholeness: Sacred Unity

Many have noted how the findings of science provide strong evidence that all people everywhere, past, present and future, are intimately connected to one another, and equally to everything else in the universe. Physics and chemistry teach that matter and energy once formed an infinitesimal totality, a ‘singularity’, which began expanding billions of years ago; that the first stars, formed of hydrogen and helium atoms, eventually collapsed and then blew apart with such tremendous force as to create and spread wide all the elements of the periodic table, which in turn led to the creation of a multitude of galaxies, including the milky way, the earth’s solar system and planets, all parts and particles universally connected still by a mysterious force known as ‘quantum entanglement’. Biology, in turn, shows that the same stardust atoms contributed to carbon-based life-forms that share a genetic heritage and evolutionary pathway towards the astonishing diversity and sophistication of life on earth today. Vital oxygen is produced in green plants by photosynthesis, a process entrapping light energy from the sun. The same oxygen, combined with carbon, is taken back up by plants and re-used in a continuous cycle; those same plants forming essential components of the food chain on which human life depends.

Such observations make clear that the life of every person on earth is inextricably tied to nature. Psychology reveals, in addition, that human beings share universal faculties, including the five senses; being able to learn, think, calculate and reason; the ability to speak and act; and the spectrum of painful and pain-free emotions. Sociology and anthropology in turn reveal significant commonalities of social groupings and behavior. Scientific knowledge like this across the dimensions, when contemplated with due dispassionate care, will encourage a person’s transitional development from Individual Stage 4 to Integration Stage 5. Something more, though, may be necessary. Knowing about wholeness and cosmic unity from an intellectual standpoint is not the same as realizing it, knowing it, making it real as a deeply held personal truth. Compare, for example, how a candle must first be fashioned over time before a single brief spark of ignition lights its flame in just an instant. Similarly, breakthrough insights or ‘epiphanies’, visionary personal experiences, “Like flashes of lightning”, as Arasteh described, offer indelible glimpses of a seamless and sacred unity throughout all five dimensions of the universe, but depend on appropriate preparation.

The necessary conditions tend to accrue gradually, almost imperceptibly over time, through reflecting on science as described, on contemplating wisdom literature, also through the processes described of emotional healing of losses and threats accompanied by natural psychological growth and development. In some cases, such an awakening may come with similar great force when a relatively unprepared person suddenly and unexpectedly experiences her- or himself as intimately linked to everyone else, living, deceased and to come, to nature and the greater cosmos, and to the divine realm of a supreme overarching spirit or universal life force. Such episodes of ‘spiritual emergence’ can prove highly destabilizing, to the extent of being considered spiritual crises or emergencies, with characteristics resembling those of manic episodes or other forms of psychotic mental illness. When this occurs, a person will assuredly benefit from contact with people already advanced on the journey towards spiritual maturity, people who can recognize what is happening to them and so provide protection, reassurance and guidance.

For the majority, less harmfully affected, having experienced a glimpse of such a vision of indivisible wholeness, the major task becomes to incorporate it centrally into one’s life. To enter and move forward through Stage 5 ideally involves actively pursuing wisdom, which can perhaps best be achieved through developing spiritual skills and so by engaging in a regular routine of spiritual exercises or wisdom practices.

7. Spiritual Skills

Two of the most useful wisdom practices are ‘contemplation’ and ‘meditation’, through which regular, disciplined practitioners will become increasingly skilled in these key activities. The two words are sometimes used interchangeably but are intended here as having different meanings.

Contemplation involves studied, dispassionate (ego-free) reflection aimed at both exploring and expanding one’s personal experience and understanding in relation to human existence. Reflective practice of this type is increasingly being taught and encouraged, for example in pastoral and health and social care training schemes [

30] (pp. 127–139).

Meditation, together with similar activities such as ‘mindfulness practice’, ‘silent prayer’, and ‘stilling’ aims at concentrating the mind. It involves remaining still and silent, usually kneeling or seated, for set periods of time, typically twenty to thirty minutes once or twice daily, while bringing conscious awareness to focus throughout on a still point, such as a word or short spiritually meaningful phrase (called a ‘mantra’), or on a regularly repeating phenomenon such as the passage of breath inwards and outwards through the nostrils. It is likely that ‘meditation’ and ‘medicine’ share the same Sanskrit root, ‘med-’, which can be extended to refer equally to ‘healing’ and ‘making whole again’. The process allows the contents of mental activity—principally thoughts, emotions, sense perceptions and impulses—to be observed but not pursued or acted upon, allowing the mind to settle and achieve a concentrated state of tranquility.

Meditation works well as an aide to contemplation. Other benefits of the practice have been established over many centuries and according to several faith traditions, including Buddhism [

31], Hinduism [

32], and Christianity [

33]. None of these, however, because of the mind-emptying nature of meditation, affix any specific religious doctrine or content to the practice. Secular forms of meditation, essentially the same in nature according to which a person sits in silence, quietening the mind, have also more recently been developed and are widely practiced as an aid to general well-being. Secular-style ‘mindfulness’ has also been successfully introduced as a therapeutic component of medical and psychiatric care, effective particularly in the treatment of chronic pain, psycho-somatic disorders and depression [

34,

35]. Meditation practice (typically involving shorter periods) is also increasingly being recommended for teaching in schools [

36]. Meditation can also be undertaken effectively while moving, such as while walking in a circle, and by ‘whirling’ to music, as in the Sufi dervish tradition.

Neuropsychologists have clarified what happens at the physical and biological levels during meditation. Electro-encephalographic recordings show an increase in alpha-wave activity associated with a state of relaxed wakefulness, and with greater synchronization of such activity occurring between the two brain hemispheres. Advanced meditators also demonstrate an increase in lower frequency theta-wave activity, associated with the creative subconscious mind [

37] (pp. 96–100). Imaging studies also show consistent changes during meditation, with typically an increase in activity recorded in the attention association area of the frontal lobe, and a corresponding decrease in activity in the orientation association and visual association areas of the parietal lobe. With sustained attention, communication between the hemispheres is found to be increasingly coordinated, with both left and right orientation and verbal-conceptual association areas being switched off. A quiescent right orientation association area gives rise to a sense of unity and wholeness, while lack of activity in the left orientation association area results in the dissolving of the self/non-self-boundary [

37] (pp. 80–93). The importance of integrating left and right brain functioning into whole-brain harmony, in the interests of wisdom and healthy cultural development, has been extensively explored by Iain McGilchrist [

38].

Additional spiritual skills associated with contemplation and meditation include

Discernment, wise judgement that is enabled through emotional tranquility. In the absence of anxiety, bewilderment and doubt, thought content appears calm, lucid and assured.

Objectivization of subjective experience, as described by Arasteh [

21] (p. 61), depends on the calm, clear-minded ability of the meditator to observe dispassionately the thoughts, sense perceptions, emotions and impulses that arise during periods of contemplation and in meditation sessions in a way that allows subsequent recall and lucid description of the contents of the mind.

Lexithymia, a specific example of objectivization of subjective experience, is the ability to identify emotional experiences by name. This is of value because naming emotions when they arise affords a strong measure of control regarding the effect of such feelings on a person’s thoughts, words and actions.

Self-control, including the ability both to ‘release’ (to swiftly capture an emerging opportunity) and to ‘restrain’ (to pause, defer and consider a response). In some instances, the latter involves ‘lexithymia’ because the ability to identify, for example, “I am angry”, or, “I am sad”, serves to short circuit the experience and reduce its intensity. Meditation practice aids self-control by producing firstly the sense of having an additional split-second of time to decide about a course of action, and secondly unqualified confidence about whether or not to proceed.

Empathy, the ability to experience by direct transmission the emotional state and feelings of another person.

The word ‘empathy’ is often used inter-changeably with ‘sympathy’, but the two are better differentiated as follows. Sympathy can occur at a distance; empathy is more intimate, arising only when people are in close contact, based on the contagious nature of emotions. Sympathy occurs when someone reads, hears about or sees others in a predicament of suffering and feels regret, standing in the other’s shoes and imagining what it would be like, then responding appropriately, perhaps with anger, sorrow, guilt or any combination of painful emotions. These are personal feelings ‘on behalf of’ another. Empathy, on the other hand, can be considered a developed form of a natural human ability that requires a higher degree of self-awareness, such as attends advanced skill in meditation practice. Accordingly, when encountering someone, either at close quarters or perhaps on screen, who is experiencing emotions, whether strong or subtle, painful or pain-free, there is direct transmission between the two, such that the skilled practitioner can identify within him- or herself the emotion state experienced by the other. This will obviously be helpful in the practice of psychiatry, clinical psychology and psychotherapy, enabling the professional to name for them the feelings of patients and clients who may be relatively alexithymic, which is to say unable to name emotions for themselves. It is beneficial to be able to identify for someone that, for example, they seem to be angry, afraid or ashamed, as it opens up fruitful lines of enquiry, and—by giving tacit permission—provides the encouragement necessary for further cathartic unburdening.

Two additional benefits follow in this setting—aside from new information arising about the painful emotions and their causative antecedents, and the therapeutic release of emotional energy: firstly, improved trust felt by the patient regarding the therapist, frequently accompanied by improved co-operation with treatment; secondly, the effect of flow in the other direction of feelings related to the presence and resilient good humor of a well-integrated therapist. Such calm, confident, accepting feelings, resonant with an underlying capacity for joy, contribute highly effectively to the lift in spirits, the psychological support that the other seeks and needs.

8. Wisdom Practices (Spiritual Exercises)

Being skilled at both contemplation and meditation will also significantly enhance fruitful engagement with the various other wisdom practices, those activities which equate with the spiritual exercises of ancient Greek philosophers. According to Hadot, all of these, “Consist, above all, of self-control and meditation” [

7] (p. 59). By ‘meditation’, he is referring to, “The exercise of reason... a rational, imaginative, or intuitive exercise that can take extremely varied forms”, a definition which surpasses intellectualization, approaching more closely what is referred to in this paper as contemplation.

Hadot’s list of spiritual exercises—which, to repeat, he describes as, “Fundamentally, a return to the self, in which the self is liberated from the state of alienation into which it has been plunged by worries, passions and desires” [

7] (p. 103)—includes the following: ‘research’, ‘thorough investigation’ (skepsis), ‘reading’, ‘listening’, ‘attention’, ‘self-mastery’, and ‘indifference to indifferent things’ [

7] (p. 84). Attention (prosoche), for example, means, ‘Attentive concentration on the present moment’, and is a skill strongly associated with freedom from the passions, thus from both attachments and aversions that provoke intensities of emotion. Such attentiveness, he says, “Allows us to accede to cosmic consciousness, by making us attentive to the infinite value of each instant, (and) causing us to accept each moment of existence from the viewpoint of the universal law of the cosmos [

7] (p. 85)”. This universal law includes the laws of nature that are the focus of, and may be elucidated by, scientific enquiry. It is equally the law that underpins wisdom, serving to emphasize the mutuality of science and wisdom, two sides of the same precious coin, inseparable aspects of humankind’s relentless searching for ultimate knowledge.

Hadot expresses the view that, “In order to recognize wisdom, we must, so to speak, go into training for wisdom” [

7] (p. 261). There may be no better time for this in a person’s life than late adolescence when embarking on a university course, and no better courses in which to include such training than those of philosophy and psychology. Students will doubtless have been selected in part by demonstrating some facility regarding contemplative practice, for example by being able to concentrate sufficiently well as to study for and succeed on courses in school and college requiring imaginative autonomous thinking. Meditation practice, requiring only simple instructions, is also relatively easy to teach.

From the beginning of any course of study, in the fields of both philosophy and psychology, an expectation for students to adopt some form of daily wisdom practice routine is recommended as part of what might be called (depending on preference) a Personal Growth Program (PGP) or Spiritual Development Plan (SDP), the simplest of which might consist of five parts:

- (a)

Regular quiet time (for meditation and contemplation);

- (b)

Appropriate study (of material from philosophy and developmental psychology; from science; from wisdom literature, scripture and other spiritually inspiring matter);

- (c)

Seeking and maintaining supportive friendships with others sharing similar humanitarian aims and spiritual values;

- (d)

Regular acts of service to others, actions prompted by kindness and compassion;

- (e)

Time spent engaging with nature.

These activities tend to be mutually beneficial. A daily walk, for example, could involve a fruitful combination of quiet time that is spent in the contemplation of nature. To give another example, group meditation practice often promotes the formation of supportive friendships. The benefits are cumulative as practitioners persist. The skills acquired grow to extend well beyond the actual daily sessions.

Meditation involves more than simply employing a reliable technique. It is a mysterious process that occurs spontaneously as a gap opens up when the mind becomes engaged purely with itself, a time during which it is more likely that ‘something happens’ to promote spiritual growth than during everyday waking consciousness. People may need continuing guidance and sympathetic encouragement to persist; and to be told that the only way genuinely to assess the benefits of meditation, and to harvest its considerable rewards, is to engage in and persevere with the practice, undertaking it as rigorously and purposefully as any scientific experiment. It may help those unfamiliar with the practice to know that neuroscience research has shown that even short periods of regular meditation can reshape the brain’s neural pathways, increasing those areas associated with kindness, compassion and rationality, while decreasing those involved with anxiety, worry and impulsivity.

In the prevailing secular, materialist global culture of today, rigidly dogmatic religions and fundamentalist belief systems are considered at best with suspicion, often as wholly destructive. In terms of promoting wisdom, however, the value of some religious practices bears re-examination, particularly—as with meditation and silent prayer—they can be seen to have secular equivalents. Folk traditions and rituals, for example, compare with religious worship and other forms of sacred rite; contemplative reading of poetry, philosophy and literature may validly be compared with reading works of wisdom and scripture.

Other religious practices include listening to, singing and playing sacred music; undertaking spiritual retreats, and going on pilgrimages to sacred sites; also doing vocational and charitable work. Their secular equivalents include engaging with uplifting or ‘soulful’ music, through listening, singing, chanting, playing and dancing; visiting places of outstanding natural beauty; and regular acts of kindness and compassion.

Furthermore, whether religious or not, people utilize additional similar methods in aid of deeply personal refreshment and renewal, including keeping a journal in which to record personal reflections; maintaining stable and loving family relationships and friendships; engaging with and enjoying nature by making use of the sea, mountains and countryside, spending time outdoors in wilderness places, conservation reserves, parklands and gardens; undertaking regular physical activity and keeping healthy; indulging in an appreciation of the arts; and, engaging in creative activities.

These practices, too, can be combined in mutually beneficial ways. Gardening, for example, offers opportunities for contemplation, also ways of taking exercise while engaging with nature. Such a list also provides a rough guide for people to carry out a form of personal inventory and establish what they may already be doing, consciously and deliberately or otherwise, to further progress in life through the six stages towards wisdom. Such a list may also provide a person with new options to consider incorporating into their wisdom practice routine, PGP or SDP.

Just as people come together in churches, synagogues, mosques, temples and gurdwaras, not only to cement their faith and worship but also to engage in community activities and communal life, so do secular groupings arise to engage in co-operative activities of a sporting, educational, recreational, and charitable nature, together with other types of group work and play, all in ways that involve a special quality of non-partisan bonding and friendship. When spiritual values are adopted and adhered to, harm and suffering are avoided. Great psychological and social benefits naturally follow.

9. Timeliness

The ancient Greek schools of philosophy, in addition to attentive concentration on the present moment, “In order to enjoy it or live it in full consciousness” [

7] (p. 59), uniformly also recommended the spiritual exercise of contemplating one’s own death, not morbidly but as a certain eventual fact. They did so on the grounds that, “The secret of joy and serenity is to live each instant as if it were the last, but also the first” [

7] (p. 225). The way matters have been developing in recent human history, this could be the ‘Kairos’ moment, the decisive and most favorable period, to go further; to contemplate in addition to personal non-existence the decimation or full extinction of our species, the wiping out of sentient humanity from the planet.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that thermo-nuclear catastrophe, global warming, and illness pandemics like COVID-19, whether alone or in combination, could present genuine threats to human life and welfare on an immense scale, even to the point of complete annihilation, either soon or within the next few generations. Climate change, and the resulting increase in number and intensity of natural disasters, is already responsible for multiple human deaths and immeasurable human suffering through tragic losses, homelessness and displacement. Widespread human belligerence, and the deployment of exceptionally destructive weaponry, are causing death, suffering and migration on a similarly huge scale. The barely manageable refugee situation is impinging on almost everyone else. Through media reporting, even those living in comparative safety become personally involved with human suffering everywhere.

Similarly, the coronavirus pandemic is bringing the immediacy of threats and losses into every home. People are encouraged and expected to behave responsibly towards each other (by wearing face coverings, maintaining social distancing, self-isolating when necessary, getting tested when symptoms arise, accepting vaccination, and so on) in ways that are at times and in some places having to be legally imposed because of resistance and a natural tendency towards non-compliance. This virus offers strong evidence of seamless human inter-connectivity, that what one does affects others, that human beings are deeply similar: chemically, biologically, emotionally and socially. Despite all obvious outer differences and diversity, without exception, human beings are therefore wisely regarded as essentially kin—an important observation for young people to be given the opportunity to make for themselves in the interests of the wider community.

Rather than responding with pessimism and despair, reflective practice reveals this overall predicament—one that involves multiple threats and associated losses—as offering people a precious and timely opportunity to grieve collectively and grow in consequence; much as at times of significant public funerals of royal figures and service personnel killed on active duty; and also to recognize the destructive absurdity of rivalry and conflict, and the universal advantages of co-operation and kindness.

10. Additional Considerations

Unfortunately, COVID-19 is not the only disorder causing havoc throughout the world today. For some time, psychiatrists, psychologists and psychotherapists have been dealing with epidemic levels of anxiety, depression, insomnia, eating disorders (including obesity) and addiction disorders, tackling them necessarily on a case-by-case basis. An overview of the situation suggests, though, that social and cultural factors are contributing, and a broader remedial strategy is therefore required.

It can readily be understood that people experiencing psychological disorders, like those mentioned, are responding to the high levels of threat and loss that are impinging on their lives. Western, secular, materialist culture leaves those in the earlier stages of personal development vulnerable to a daily onslaught of painful emotion, doubts about self-worth, and a vicious cycle of diminishing ability to cope with the demands of daily life, usually coupled with troubled and troubling interpersonal relationships. This has hitherto been ‘medicalized’ with the application of diagnoses and the intensive use of potentially addictive pharmaceutical treatments, as well as some psychotherapy. For the sake of brief episodes of relief from feeling bad, people also self-medicate with harmful substances including nicotine, alcohol, ‘recreational’ drugs and other habit-forming intoxicants. For similar reasons, people engage in unhealthy, also potentially-addictive, behaviors including excessive work habits, unnecessary spending, incautious thrill seeking, unhealthy over-eating, compulsive sexual activity, obsessive gaming and gambling.

More successful than prescribed medicines for these problems are healing processes that involve being transformed rather than overwhelmed, through experiencing, rather than avoiding, painful emotions. Methods that allow this to happen gradually, with the affected person feeling supported throughout, include mindfulness-based programs, already mentioned, and newer forms of spirituality-orientated psychotherapy, for example ‘Inner View’ therapy [

39], according to which, “Symptoms are viewed as harbingers of growth”, and that, “(What) appears to be a psychiatric disorder… does not have the last word on the true nature of the person” [

39] (p. 50). A spiritual approach is also central to the successful twelve-step method for addictions pioneered by Alcoholics Anonymous, which includes, “Making a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understand Him” (Step 3), “Making a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves” (Step 4), “Admitting the exact nature of our wrongs” (Step 5) and, “Humbly asking God to remove our shortcomings” (Step 7) [

40] (p. 59). To follow a daily routine of wisdom practices, acquiring and developing spiritual skills, will reliably have protective and preventive, as well as remedial effects against anxiety, depression and addiction behavior.

Protection comes from feeling secure, valued and loved, from living in an environment of affection, trust and hope for the future, and depends therefore on healthy family relationships, and similarly on prevailing, conflict-free community and cultural interactions. Worldly aims, ambitions, values and priorities, typically associated with the prevailing Western, secular, materialist, economic and political culture, focusing competitively on the acquisition of wealth, possessions and power, can be said to underpin the many stark problems facing humanity, going as far back as the industrial revolution and the colonial era of human history: territorialism, racial and religious intolerance, growth economics and consumerism, technological progress and the associated demand for fossil fuels with consequent ecological destruction and global warming, all included. Holistic or ‘spiritual’ priorities and values, in contrast, focus on liberty, equality, kinship, humility, simplicity, frugality, honesty, courage, hope, love, compassion, and wisdom.

While there is always the possibility of tension between the two, worldly ambitions can be said to dominate the lives of people at the earlier psychological development Stages, 3 and 4, while holistic or spiritual values emerge as increasingly influential during the more mature Stages, 5 and 6. Wisdom involves taking responsibility. Time used for wise reflection offers a precious opportunity to make a corrective uplift to hitherto spiraling-down trajectories of intolerant attitudes and mercenary values, resulting in the confused and shambolic situation the world’s population now seems to be in. The opportunity is available, and seems increasingly urgent, for many to learn better to defend and protect themselves and each other from harm, not only from viral and other forms of sickness, but from global warming and everything else that is threatening.

11. Consequences for Academic Departments

Many schools already include meditation practice (also known as ‘mindfulness’ or ‘stilling’) as part of their pupils’ routine [

36,

41,

42]. In Scotland, the non-profit ‘Association for Character Education’ [

43], a community for schools, organizations and individuals, runs the ‘Inspiring Purpose: Global Citizens In The Making’ program, a well-established character discovery activity for young people aged 10–16. In over ten years, more than 300,000 young people have taken part in this educational process, which has been designed to “Help them to define their purpose and their goals” and has been “Proven to enhance their self-knowledge and self-awareness, as well as encouraging them to search for inspiration and define their aspirations for the future” [

44].

In addition, in some schools, the entire curriculum is centered on a program of ‘character education’, based on positive psychology, particularly the work of Martin Seligman and colleagues [

3]. According to one English state-maintained school, for example, “Student (examination) results—although important—are not the only area in which we want students to be their best. We believe the development of character strengths is equally important if our students are to flourish both at school and in their ongoing lives”. The model used, “Focuses on the eight character strengths that most strongly underpin progression towards happy, engaged, meaningful and successful lives” [

45]. These strengths start with a ‘growth mindset’ coupled with ‘understanding others’, and include curiosity, zest (enthusiasm), gratitude, grit (determination), self-control with learning, and self-control with others.

School leavers educated according to such programs will assuredly seek similar and more advanced opportunities for continuing personal development. Those responsible for teaching philosophy and psychology in university departments are wise, therefore, to consider making appropriate adjustments to undergraduate courses. Some guidance is available, for example in a report on teaching spirituality and health care to medical students [

46] (pp. 22–27). Despite the apparent urgency associated with global warming and the COVID-19 pandemic, personal development and changes in social attitudes both take time. Patience and perseverance, coupled with confidence in a positive long-term outcome, are required. An evolutionary approach is therefore likely to prove more successful than a revolutionary one. Everyone concerned may therefore be reassured that no drastic or dramatic changes are required to existing curricula, with two exceptions. Firstly, subject matter pertaining to schemes of psychological development throughout life should be included to help students understand why there should also, secondly, be the gradual introduction of wisdom exercises, including the regular practice of both contemplation and meditation.

Teachers remaining hesitant to take even this first double step are advised at least to consider discussing its possible merits with prospective and current students, canvassing their views too on other points raised here; for example, on taking a personal, self-administered and confidential wisdom assessment or spiritual inventory, and on also preparing a regular personal routine, PGP or SDP. There is no need for concern about how to assess and examine students, as this may proceed largely as before, based on the existing syllabus, with essays, question papers and questionnaires covering the same topics. Only some additional questions about personal development may be needed.

More adventurous teachers—especially later, when students have become reasonably adept at contemplation and meditation—may consider encouraging reflective practice by fostering further skills development regarding, in particular, ‘objectivization of subjective experience’, and ‘empathy’, following this up by suggesting and supervising small-scale research projects based on these skills. Some course leaders may even find themselves taking delight in discovering that, initially, they are learning interesting new material and developing new skills alongside those they are teaching, learning in turn from them all the while.

With growing confidence, teachers might include regular group meditation sessions for their students several times weekly, as well as short periods of reverential silence at the beginning and end of classes and lectures. In the interests of broadening experience, bringing to the fore of consciousness matters that previously only impinged subliminally on students’ minds, teachers might also introduce ‘experience experiments’ that involve thought

and feeling, rather than the more traditional ‘thought experiments’, like Philippa Foot’s influential 1967 ‘Trolley Problem’, for example, which may be less helpful because they are both hypothetical and concerned with highly improbable circumstances unlikely to be encountered in everyday situations by classroom students. Foot describes the trolley problem situation as follows: “A man is the driver of a runaway tram, which he can only steer from one narrow track on to another; five men are working on one track and one man on the other; anyone on the track he enters is bound to be killed” [

47] (pp. 1–5). The driver’s actions decide which will be lost: one man’s life, or the lives of five. Foot herself accepted that, “

In real life (my italics) it would hardly ever be certain (even when steered at) that the man on the narrow track would be killed” [

47] (p. 2); in other words, that such a thought experiment would accurately reflect reality. In contrast, ‘experience experiments’ benefit from being more lifelike and could, for example, include roleplay sessions in which, with some observing, other students act out an improvised scene. This, for example, might involve a refugee family confronting sympathetic but intransigent border guards, or small retail or manufacturing business employers meeting members of their workforce who are facing either furlough or possible redundancy during the hard times of a COVID-19 pandemic. Each short roleplay session will provide material for further reflection and discussion. Even the propensity of some students to over-indulge in sexual behavior, alcohol and illegal substance use, thrill seeking, and other self-destructive or antisocial antics can be put to good use by taking them as the deliberate focus of subsequent reflective practice.