“You’re getting old and your children don’t follow your example. Give us a king to rule over us like all the other nations”. Samuel was

bored1 at being asked for a king to rule over them, so he went to talk to the Lord. And the Lord answered Samuel: “Accept what the people propose to you. It’s not you they reject, but me, because they don’t want me to be their king” [

2].

2 1. Introduction

One day, Aristotle pronounced: “The totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something besides the parts; there is a cause” [

3]. He arrived at this conclusion by reviewing and critiquing all the available knowledge that preceded him. Here, in this reflection presented to you, I seek to adopt a similar attitude to Aristotle, almost 2.5 millennia later, and also to review and reconsider, in the style of narrative reflection and theorising, the knowledge available up to the present day. These introductory examples are not intended as historical claims but as illustrative frames that highlight the longstanding human attempt to interpret experiences of estrangement, thereby preparing the conceptual ground for the existential-phenomenological analysis that follows.

Boredom is a common experience in the lives of many people, often considered merely as a passing emotion or a temporary state of dissatisfaction. However, this study proposes an innovative approach by addressing boredom as a deeper and more significant phenomenon: the Theory of Boredom as a Sign of Existential Disconnection.

This theory suggests that boredom goes beyond a simple emotional reaction, being instead an indicator of a deeper disconnection between the individual and the world around them. Rather than being just a momentary mental state, boredom is interpreted as a warning sign, a call to attention for a lack of authentic engagement with one’s own existence.

In this context, the Theory of Boredom as a Sign of Existential Disconnection seeks to understand boredom as a symptom of a broader existential disconnection. It challenges the traditional view of boredom as something trivial, highlighting it as an important indicator of the need for deeper reflection on the relationship between the individual and the world around them.

This article does not aim merely to compile philosophical and psychological contributions on boredom, but to critically articulate how such perspectives converge to ground the Theory of Boredom as a Sign of Existential Disconnection. Rather than treating these traditions as parallel lines of thought, the present work proposes a conceptual synthesis in which existential, phenomenological, and psychological dimensions operate together in shaping a unified theoretical framework.

By exploring this theory, we can not only expand our understanding of boredom but also shed light on broader issues related to the search for meaning, authenticity, and connection in human life. This reflective and narrative study aims, therefore, to open new avenues for investigation and reflection on the human experience, offering a unique perspective on boredom and its role in each individual’s existential journey. The central research question guiding this article is: to what extent can boredom function as a phenomenological indicator of existential disconnection? I argue that a specific form of boredom—distinct from ordinary situational boredom—emerges when the subject loses access to a meaningful horizon of possibilities.

The epistemic scope of this article is primarily phenomenological and conceptual. It does not aim to provide a causal model of boredom, nor to identify universal psychological mechanisms. Rather, it offers a descriptive-analytic framework for understanding how certain experiential structures—temporal articulation, evaluative resonance, embodied attunement, and imaginative projection—can weaken in ways that yield a distinctive form of existential disconnection. The claims advanced here are therefore interpretative and phenomenological in nature, and should not be taken as asserting empirical generalisability.

1.1. Distinguishing Existential Boredom from Adjacent Concepts

“We don’t know almost nothing about boredom” [

4]. A clear conceptual distinction between existential boredom

3 and neighbouring phenomena is essential for avoiding category errors and for situating the present theory within a coherent philosophical and psychological landscape. The following subsections outline how existential boredom differs from ordinary situational boredom, cognitive under-stimulation, Heidegger’s analyses of boredom and Unheimlichkeit, Frankl’s existential vacuum, and clinical apathy or anhedonia.

1.1.1. Ordinary/Situational Boredom

Ordinary or situational boredom refers to transient states of disengagement that arise when the environment is monotonous, predictable, or insufficiently stimulating. These episodes typically occur during routine or repetitive tasks and do not carry substantial existential weight. They involve mild frustration or restlessness but do not fundamentally alter the individual’s relationship with meaning or world-disclosure. Such states are commonly understood as short-lived and context-dependent, lacking depth and ontological significance [

5]. Boredom is “the aversive experience of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity” [

5].

1.1.2. Psychological Under-Stimulation

Psychological accounts of boredom frequently conceptualise it as a failure of attentional engagement. Eastwood et al. characterise boredom as “the aversive experience of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity” ([

5] p. 482). This model emphasises cognitive under-stimulation and diminished attentional control, wherein the mind becomes unanchored and unengaged. Subsequent work expands this view by linking boredom proneness to impaired self-regulation, reduced perceived agency, and difficulties in sustaining meaningful attention towards tasks [

6,

7]. While such states can be distressing, their structure is primarily cognitive and motivational rather than existential. Ros Velasco highlights that boredom varies across intensity, duration, and context, making it a multidimensional rather than uniform experience [

4].

1.1.3. Heideggerian Profound Boredom

Heidegger’s analysis of profound boredom (tiefe Langeweile) describes a mood in which the world as a whole recedes into indifference. In this state, “all things and men and oneself … are removed into a remarkable indifference” [

8,

9]. Profound boredom discloses the temporal structure of Dasein by stripping everyday significance from phenomena, thereby revealing the ontological background against which meaning ordinarily arises [

10]. In profound boredom, “time becomes long … we do not want to have a long time, but we have it nevertheless” [

8]. Slaby describes profound boredom as a “fundamental attunement” that reveals “the nothingness at the heart of being” [

11]. Although there is thematic overlap with existential boredom, Heidegger’s account aims at unveiling fundamental structures of being, whereas the present theory concerns a more modest phenomenological suspension of meaningful possibilities.

1.1.4. Heideggerian Unheimlichkeit

Unheimlichkeit, often translated as “uncanniness” or “not-being-at-home”, is distinct from boredom. As Slaby notes, Heideggerian uncanniness exposes the groundlessness of existence, rather than a loss of meaning linked to agency [

11]. It denotes an existential exposure to the groundlessness of human existence, revealed most clearly through anxiety (Angst) [

12]. Whereas profound boredom dissolves the significance of beings, Unheimlichkeit reveals the ontological condition of being thrown into a world without ultimate foundations. It exposes the nothingness underlying Dasein and evokes a destabilising sense of estrangement. As such, Unheimlichkeit is more radical and metaphysically charged than the form of existential boredom treated in this article.

1.1.5. Frankl’s Existential Vacuum

Frankl’s notion of the “existential vacuum” describes an inner emptiness resulting from a blockage or loss of meaning. It manifests as apathy, feelings of futility, or a pervasive sense of purposelessness [

13]. For Frankl, this vacuum reflects a disruption in the will-to-meaning, which can generate what he termed “noogenic neuroses” [

13]. Although existential boredom may coincide with or signal aspects of this vacuum, Frankl’s notion emphasises an overarching deficiency in existential direction, whereas the present account is concerned with phenomenological shifts in meaningful attunement rather than with a global collapse of purpose. Frankl describes the existential vacuum as “an inner emptiness” resulting from a blockage of the will-to-meaning [

13].

Unlike Frankl’s existential vacuum, which describes a persistent loss of direction rooted in a blockage of the will-to-meaning, the form of existential boredom developed here concerns a temporary phenomenological suspension of meaningful attunement rather than a structural or enduring collapse of purpose.

1.1.6. Apathy and Anhedonia (Clinical)

Apathy and anhedonia are clinical constructs distinct from boredom. Apathy involves a persistent reduction in motivation, initiative, and emotional responsiveness, often linked to neurological or psychiatric conditions. Anhedonia refers to a diminished capacity to experience pleasure [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Importantly, boredom typically involves a desire for meaningful engagement—one wants to act but cannot find significance—whereas apathy reflects an absence of desire altogether. Goldberg et al. argue that boredom remains distinct from apathy because the bored individual “wants to engage but cannot,” whereas the apathetic individual “does not want to engage at all.” [

15]. Empirical work in disorders such as Parkinson’s disease demonstrates that apathy and anhedonia are measurable clinical syndromes with specific neuropsychological correlates [

20]. These conditions therefore differ fundamentally from existential boredom, which retains an orientation towards meaning even as meaningful possibilities withdraw.

1.1.7. Concluding

Existential boredom is a phenomenological condition in which the subject undergoes a temporary suspension of access to a meaningful horizon of lived possibilities, expressed through disruptions in temporal directedness, embodied intentionality, and evaluative attunement.

1.2. Why Existential Boredom Is Still Boredom: A Phenomenological Justification

A central conceptual concern may arise regarding whether what is here termed existential boredom should properly be classified as a form of boredom at all. This concern stems from the apparent difference between the causes of ordinary boredom (e.g., monotony, low stimulation, task under-engagement) and the conditions in which existential boredom emerges (e.g., suspension of meaning, loss of evaluative grip, contraction of lived possibilities). To address this, it is necessary to clarify the phenomenological criterion according to which both states can be considered modalities of the same affective genus.

Across psychological and philosophical accounts, boredom is characterised not primarily by its external causes but by its affective structure: a tension between (a) a desire for meaningful engagement and (b) the inability of the present situation—or one’s orientation toward it—to afford such engagement. This structure is preserved in both ordinary and existential boredom.

A potential concern is that the phenomenon described as existential boredom might overlap with other affective conditions such as apathy, depression, or certain anxiety states. This overlap is only superficial. Clinical apathy typically involves a reduction in motivational drive, and depression is often marked by pervasive affective flattening. In existential boredom, by contrast, the desire to engage meaningfully is preserved; what fails is the subject’s access to meaningful affordances. The subject still wants significance but is temporarily unable to locate it within their horizon of possibilities. This difference in motivational structure distinguishes existential boredom from clinical affective disorders without denying that, in some cases, existential boredom may coexist with or precipitate them.

A phenomenological illustration helps clarify the relationship between ordinary and existential boredom. A person may feel bored during a repetitive meeting because the task provides insufficient affordances for meaningful engagement—this is ordinary boredom. Another person, after a major disruption in their life narrative, may find that no available project, activity, or future possibility presents itself as meaningful—this is existential boredom. In both cases, the subject experiences a felt gap between the desire to engage and the inability to find significance. What differs is the locus of the blockage: situational in the first case, horizon-wide in the second. This continuity of affective structure justifies the use of the common term boredom while acknowledging the profound qualitative difference between its modalities.

What differentiates them, therefore, is not the core affective configuration but the level at which the blockage occurs. In ordinary boredom, the blockage lies at the level of situational affordances. In existential boredom, the blockage lies at the level of the subject–world relation itself. Thus, existential boredom extends—but does not break with—the essential structure of boredom. It represents a deepening of the same affective form, not a departure from it.

The use of the common term boredom remains justified because the experience retains the defining phenomenological core: a felt gap between wanting to engage and being unable to find significance in available possibilities. The shared affective structure ensures that existential boredom belongs to the broader family of boredom phenomena while constituting a distinct and higher-order modality.

2. The Boredom as a Sign of Existential Disconnection Theory—The Genesis

Methodologically, this article employs a comparative phenomenological analysis, integrating insights from existential philosophy, existential psychology, and contemporary phenomenology to clarify the lived structures through which boredom manifests as a suspension of meaningful attunement.

The theory of boredom as a sign of existential disconnection arises in response to an incessant personal quest for truth and the true reason for existence, as well as to an increasingly evident restlessness in the contemporary human experience (see

Supplementary Material S1). In a world saturated with external stimuli and marked by the superficiality of interactions and experiences, a sense of emptiness, a lack of meaning permeates people’s lives. It is in this context that the theory takes shape, as an attempt to understand and give voice to this diffuse feeling of discontent.

Boredom is a discrete emotion associated with feeling dissatisfied, restless, and unchallenged when one interprets actions and situations at the present time as purposeless [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Boredom, often seen as a mere passing disturbance, reveals itself as a symptom of a deeper disconnect between the individual and the world around them. The constant bombardment of information and superficial stimuli contributes to a sense of alienation, where experiences seem devoid of genuine meaning.

The theory arises from the need to name and make sense of this experience, to shed light on the underlying roots of boredom and its implications for human life. It emerges as an invitation to reflect on how we live and relate to the world, urging us to question the validity of an existence guided by the relentless pursuit of entertainment and instant gratification.

The birth of the theory is motivated by the search for a deeper understanding of the human condition and the aspiration for a more authentic and meaningful life. It emerges as a call to action, an invitation to reconnect with our deepest values, authentic relationships, and the pursuit of a broader meaning in life.

The definition and chosen name for the Theory of Boredom as a Sign of Existential Disconnection is “Theory of Subjective Anomie”. This is because “anomie” refers to a state of disorder or lack of norms, and “subjective” emphasises the individual experience of this disconnection. Thus, this name suggests the idea that boredom arises when individuals feel disconnected from the world around them, leading to a sense of internal disorder and lack of direction.

Although the term “anomie” originates in sociological accounts of normlessness, the usage adopted here is explicitly phenomenological. “Subjective anomie” refers not to the breakdown of social norms but to the lived experience of a weakened grip on meaning and possibility. This reconceptualization retains the original term’s connotation of disorientation while shifting its explanatory locus from societal structures to first-person experiential conditions. In this sense, subjective anomie describes a mode of existential disconnection rather than a sociological state.

Ultimately, the theory of boredom as a sign of existential disconnection emerges as a philosophical response to the crisis of meaning that permeates contemporary society. It challenges us to look beyond superficial distractions and to seek a life rooted in authenticity, reflection, and the pursuit of a higher purpose. It is essential to emphasise that not all forms of boredom arise from existential causes; the theory developed here concerns only a specific modality associated with a loss of meaning, and does not claim to replace broader psychological, cognitive, or social explanations.

For a more critical engagement with the foundational authors (see

Supplementary Material S1), the following table (

Table 1) offers an analytical comparison that highlights theoretical tensions, limitations, and their specific relevance to the proposed model.

3. Theoretical Foundations: Existential and Phenomenological Approaches to Boredom

3.1. Analytical Elaboration of Supplementary Material S1: Conceptual Contributions and Limitations

Heidegger identifies profound boredom (tiefe Langeweile) as a mood that reveals the temporal structure of Dasein by dissolving the world’s ordinary significance (Bedeutsamkeit). While his analysis emphasises the displacement of everyday involvement and the emergence of an ontological uncanniness (Unheimlichkeit), it does not equate boredom with existential disconnection as formulated in this article. The present theory aligns with Heidegger in treating boredom as a disclosure of meaning’s withdrawal but departs from him by framing existential boredom as a phenomenological indicator of a contracted horizon of possibilities rather than a displacement of being in the world as such. This allows for a more fine-grained distinction between ontological groundlessness and the more specific experience of motivational and axiological collapse discussed here.

For Sartre, the confrontation with contingency produces an affective shock akin to metaphysical boredom, where the world appears heavy, meaningless, or overwhelming in its arbitrariness. However, Sartre focuses primarily on nausea as a mode of ontological revelation rather than boredom as such. This article draws on Sartre’s insights into the destabilising confrontation with freedom but reframes boredom not as the result of radical contingency, but as the experiential signal of a breakdown in one’s teleological orientation. Sartre’s contribution clarifies how meaning’s collapse can generate affective distancing, yet the present theory emphasises a more practical, lived horizon of disengagement rather than a metaphysical revelation.

Nietzsche interprets modern nihilism as a condition in which inherited values lose their binding force, generating a form of existential fatigue akin to deep boredom. His diagnosis illuminates how the erosion of meaning produces motivational paralysis. However, Nietzsche frames this primarily as a cultural–historical condition rather than a phenomenology of boredom. In adopting his insights, this article treats existential boredom as a micro-phenomenological instance of nihilistic contraction: a moment in which values fail to animate action. Unlike Nietzsche, the present theory avoids grounding the phenomenon in a grand narrative of decadence and instead focuses on the immediate experiential structure of diminished possibility.

Camus’s absurd hero confronts a world that no longer offers intrinsic meaning or rational order. The resulting estrangement resembles existential boredom in that both involve an inability to project oneself meaningfully into the future. Camus, however, understands the absurd primarily as a conflict between rational expectation and indifferent reality. The present analysis is more phenomenological: it describes boredom as an affective constriction of the field of possible actions rather than a metaphysical judgement about the world’s lack of meaning. Camus helps clarify the experiential texture of disconnection, but the theory developed here remains more focused on the lived dynamics of motivational collapse.

Husserl’s notion of horizonality emphasises that consciousness is always oriented toward not-yet-actualised possibilities. Existential boredom closely relates to a temporary breakdown of this horizonal structure. While Husserl does not analyse boredom directly, his work underpins the interpretation developed here: existential boredom is conceptualised as a suspension of forward-directed intentionality. The limitation, however, lies in Husserl’s lack of attention to affective life; thus, his framework requires supplementation by phenomenologists who foreground mood and embodiment. The present theory integrates Husserlian horizonality with affective phenomenology to produce a richer account.

Merleau-Ponty’s insights into embodied intentionality illuminate how the body anchors the world’s practical significance. Existential boredom can be described as a disturbance in the habitual structures that ordinarily confer meaning on our actions. When habitual engagement falters, the world appears flat or inert. Merleau-Ponty does not theorise boredom directly, but his account of bodily intentionality helps explain why existential boredom feels like a loss of attunement to meaningful action. The limitation is that he focuses less on existential disruption and more on perceptual and motor structures; the present theory extends his framework into the existential domain.

Frankl explicitly identifies a modern “existential vacuum,” marked by a chronic sense of emptiness and lack of direction, which closely resembles the phenomenon addressed here. However, Frankl interprets this primarily in therapeutic and moral terms, emphasising the need for purpose-oriented responsibility. The present theory adopts Frankl’s intuition that loss of meaning generates affective disconnection but refrains from prescribing normative solutions. Instead, existential boredom is treated descriptively as a phenomenological state that reveals disorientation without assuming a specific moral or therapeutic programme. Frankl is thus a conceptual ally, though the present account remains analytically rather than normatively oriented.

In summary, existential boredom marks a transient and experiential narrowing of lived possibilities, whereas the existential vacuum refers to a more pervasive and long-standing deprivation of meaning.

Rollo May analyses existential crises through the lens of anxiety and the confrontation with freedom. His work helps clarify the conditions that make existential boredom possible: when the individual cannot actualise meaningful possibilities, a paralysing affective state emerges. However, May tends to fold boredom into broader categories of existential anxiety, thereby losing the specificity of boredom as a distinct mood. This article diverges by treating boredom not as a variant of anxiety, but as its own kind of affective signal—one that marks the collapse of meaningful engagement rather than the threat of overwhelming freedom.

3.2. Towards an Integrated Conceptual Framework of Existential Disconnection

The theoretical corpus presented in

Supplementary Material S1 does not merely provide a genealogical backdrop to the proposed Theory of Boredom as a Sign of Existential Disconnection; rather, it constitutes a dense conceptual foundation that enables a deeper understanding of boredom as a distinct mode of human estrangement. Across existential philosophy, existential psychology, and phenomenology, there emerge convergent modes of describing a fundamental condition in which the subject becomes unable to inhabit a meaningful world. This section seeks to articulate these lines of thought into a coherent conceptual framework. To avoid conceptual redundancy, the following synthesis integrates the preceding contributions into a unified framework that clarifies the distinct phenomenological dimensions of existential boredom.

3.2.1. Boredom Beyond Emotional Categorization

Accordingly, I distinguish between situational boredom, psychologically driven boredom linked to low stimulation, and existential boredom, which constitutes the focus of this work. Traditional psychological models often construe boredom as a deficit of stimulation or cognitive engagement [

21,

22]. Existential thought, however, interprets boredom not merely as a quantitative absence of interests, but as a qualitative disruption in the subject–world nexus. In this register, boredom is not what happens when there is nothing to do, but when nothing that can be done discloses meaning.

This shift is central: boredom becomes a manner of being-in-the-world, not an episodic mental interruption. Thus, existential boredom signals an ontological discontinuity—an interruption in what Heidegger terms Bedeutsamkeit, the meaningful disclosedness of the world [

9].

3.2.2. Existentialist Grounds: Nihilation, Contingency, and Value Creation

In Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, the subject is confronted with the nothingness at the heart of being. Boredom is linked to mauvaise foi, the flight from one’s own freedom [

30]. In Nausea, boredom becomes an affective disclosure of contingency—things exist “too much,” and their excess of presence dissolves stable meaning. The experience is not neutral; it is metaphysically unsettling, destabilising the symbolic scaffolding that holds reality intelligible [

27].

Nietzsche’s contributions in Thus Spoke Zarathustra [

31] and Beyond Good and Evil [

32] shift emphasis from metaphysical to axiological disconnection. Here boredom signals a collapse of inherited values and the absence of self-legislated meaning. Nothing compels the subject, not because nothing matters, but because meaning has not yet been created. Boredom is an invitation to value-creation, not resignation.

Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus [

34], radicalises this by positing the absurd: the contradiction between the human desire for coherence and an indifferent universe. Boredom becomes a cousin of the absurd condition—an affect that reveals the dissonance between longing and world. Yet, Camus affirms revolt: meaning is not found, but forged.

3.2.3. Existential Psychology: Emptiness, Meaning, and Authenticity

Rollo May interprets boredom as a crisis of authenticity—a distancing from one’s own daimonic forces, the passions and drives that constitute selfhood. The self anaesthetised becomes a self estranged [

35,

36].

Frankl introduces the existential vacuum, where boredom is a diagnostic expression of meaning deprivation [

38]. Crucially, Frankl introduces a teleological dimension: boredom reflects not a collapse of reason, but the interruption of purpose. The subject could endure suffering, he argues, but cannot bear meaninglessness.

Yalom reframes boredom as a symptom of unexamined existence, pointing clinicians to engage not with distraction techniques but with ultimate concerns—freedom, isolation, death, and meaning [

40].

3.2.4. Phenomenology: Worldhood, Embodiment, and Perceptual Attunement

Husserl’s phenomenology makes a pivotal methodological contribution: boredom is not an external object of study, but a structure of intentional consciousness [

41,

42]. Boredom is part of how the world is given to us.

Heidegger, in his famous 1929–1930 lecture on profound boredom [

8], shows that Langeweile discloses time itself as emptied of significance. In boredom, time drags, not because the clock slows, but because temporality loses direction. It is important to note that, unlike Heidegger’s notion of Unheimlichkeit—a fundamental ontological uncanniness—the form of boredom analysed here concerns a loss of resonance with the world. While the two phenomena may intersect, they are not equivalent.

Merleau-Ponty adds embodiment. Boredom is not solely cognitive; it is felt in posture, breath, and movement. The body becomes heavy, the world opaque. The lived body loses its grip (prise) on reality. Thus, existential boredom includes a corporeal phenomenology of disconnection [

43,

44].

Sartre’s The Imaginary and The Transcendence of the Ego contribute the insight that imagination is a mode of world-transcendence. When imagination collapses, boredom is intensified: a shrinking of possibility-space [

28,

29].

3.2.5. Synthesis: Toward a Unified Definition

From the above, boredom in its existential form can be defined as:

a suspension of meaningful attunement to the world, wherein the subject’s temporal, axiological, and embodied engagement collapses into a horizon of diminished possibility.

Existential Boredom (EB) = df a phenomenological state characterised by (a) a contraction or stagnation of lived temporality; (b) a weakening of evaluative grip or meaningful resonance; (c) a diminished embodied readiness-to-act; and (d) a reduced capacity for imaginative projection, resulting in a temporary sense of existential disconnection.

For instance, an individual may experience a moment in which everyday activities lose their sense of relevance, future possibilities appear muted, and the surrounding world feels affectively distant. Nothing seems explicitly wrong, yet the lived horizon appears flattened. This is not fatigue, sadness, or indifference, but a suspension of meaningful attunement that exemplifies the structure of existential boredom.

The concept of existential boredom is not intended as a metaphorical embellishment of ordinary mood-states. Instead, it designates a specific phenomenological configuration in which the subject’s temporal, axiological, and embodied orientation becomes suspended or thinned. This configuration has structural features that can be described and analysed with precision, distinguishing it from metaphorical or literary uses of “boredom” that lack an articulated phenomenological profile.

Thus, existential boredom is not simply displeasure, restlessness, or dissatisfaction. It is a phenomenological thinning of the subject’s capacity to inhabit significance, disrupting:

Table 2 dimensions jointly generate a horizon in which the world appears accessible but inert, available but uninviting. The individual does not lack options but lacks meaningful orientation.

Supplementary Material S1 therefore functions not merely as an inventory of influences, but as a conceptual matrix from which the core elements of the theory emerge: suspended temporality [

8,

9], contingency [

27,

28,

29,

30] axiological collapse [

31,

32], and teleological emptiness [

37,

38].

3.2.6. Theoretical Implications for the Proposed Theory

The synthesis developed above allows for a more precise articulation of the Theory of Boredom as a Sign of Existential Disconnection. First, it becomes clear that boredom, in its existential form, operates not merely as a psychological state but as a diagnostic phenomenon capable of revealing fractures in the individual’s integration with the world, with time, with values, and with the embodied dimension of existence. Existential boredom therefore appears as a privileged affective mode through which the subject encounters the limits of their capacity to inhabit meaning, exposing a momentary suspension of significance rather than a simple absence of external stimulation.

Second, the theoretical constellation examined demonstrates that not all boredom is existential, and that the phenomenon must not be reduced to a single explanatory framework. Ordinary boredom can arise from monotony, low stimulation, or task under-engagement; these are disruptions at the level of situational affordances. Existential boredom, by contrast, arises when the subject loses access to a horizon of possibilities through which life could become meaningful—a disruption at the level of the subject–world relation. Crucially, this distinction is made on the basis of a shared affective structure (a desire for meaningful engagement accompanied by an inability to find it) combined with a different locus of blockage (situational vs horizon-wide). This combinatory criterion explains why the same term boredom remains appropriate while justifying a distinct conceptual status for existential boredom. (

See Section 1.2 for a phenomenological justification and illustrative examples).

Importantly, both forms share the same core affective configuration—an inability to find meaningful grip—but differ in the level at which this blockage occurs. Ordinary boredom concerns the failure of particular tasks or contexts to solicit involvement, whereas existential boredom concerns a disruption in the subject–world relation itself, rendering meaningful engagement in general affectively inaccessible. Thus, existential boredom is not a metaphorical extension of ordinary boredom, nor a different emotion altogether, but a structurally deeper modality of the same basic affective phenomenon.

What differentiates them (see

Table 3), therefore, is not the core affective configuration but the level at which the blockage occurs:

Third, these theoretical distinctions carry practical and methodological implications. Because existential boredom reflects a contraction of evaluative, temporal, and embodied structures, it cannot reliably be resolved by merely increasing external stimulation or behavioural activation. Interventions aimed only at enhancing arousal or novelty may alleviate ordinary boredom but will typically fail to restore horizon-wide meaningful engagement. Instead, overcoming existential boredom requires practices that re-expand the subject’s horizon of possibilities: therapeutic and existential reorientation (e.g., value-reconstruction, narrative re-authoring, practices that restore embodied attunement and imaginative projection). These recommendations are in keeping with the insights of Nietzsche and Frankl (value-creation and purpose recovery), May and Yalom (authenticity and confrontation with ultimate concerns), and phenomenologists such as Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty (re-attunement to temporality and embodiment).

Fourth, and methodologically, the theory invites a plural but disciplined research agenda: (a) phenomenological descriptions that map the micro-structure of existential episodes; (b) clinical and psychometric studies that operationalise the proposed dimensions (temporal stagnation, evaluative thinning, embodied withdrawal, imaginative constriction) to test boundary conditions; and (c) intervention studies that compare reorientation-focused strategies with stimulus-based approaches. Such empirical work would clarify when existential boredom overlaps clinically with apathy or depression and when it is a distinct, reversible threshold affect.

In sum, the theoretical implications of the model position boredom as a liminal phenomenon—situated between disengagement and transformation. It is a moment in which the subject is confronted with the collapse of inherited meanings and invited (though not compelled) to reconstitute a way of belonging to the world. Far from being merely an obstacle to well-being, existential boredom can function as a catalyst for existential reconfiguration, prompting renewed commitments and a rearticulation of one’s practical horizon.

3.3. Critical Discussion of the Theoretical Foundations

The critical examination of the foundational authors (see

Table 1) reveals that the theory of boredom as a sign of existential disconnection emerges not from a single intellectual lineage but from the convergence of several distinct yet complementary traditions. These include existential philosophy, existential psychology, and phenomenology, each offering conceptual resources that illuminate different dimensions of the phenomenon. When analysed comparatively, these perspectives disclose both points of alignment and areas of tension, which together contribute to a more precise and theoretically robust formulation of existential boredom.

The existential philosophers provide the ontological groundwork for understanding boredom as more than a transient emotional state. Sartre’s analyses of contingency and the dissolution of meaning in Being and Nothingness and Nausea highlight how human consciousness can encounter a world stripped of intelligibility [

27,

30]. Nietzsche’s emphasis on the collapse of inherited values and the imperative of self-legislated meaning shifts attention to the axiological dimension of disconnection, pointing to boredom not as passivity but as a crisis of value. Camus further expands this terrain by framing the human condition as fundamentally absurd, revealing how the search for coherence can fail within an indifferent universe. Although these thinkers do not treat boredom as a central concept, their work collectively delineates a landscape in which meaning becomes unstable, fractured, or suspended—conditions under which existential boredom is likely to arise.

Heidegger’s contributions sharpen this picture by addressing the phenomenological experience of a world that ceases to disclose significance. The notion of a suspension of Bedeutsamkeit and the temporal stagnation that emerges in profound boredom provide a framework for understanding how the subject becomes estranged from possibilities that ordinarily constitute meaningful existence. It is important to distinguish this from Unheimlichkeit, which concerns a more ontological sense of uncanniness; nonetheless, both concepts clarify how existential disconnection disrupts the fabric of everyday engagement. Phenomenology more broadly, particularly in Husserl and Merleau-Ponty, adds methodological precision by describing boredom as a modification of intentionality and as a bodily, perceptual attenuation of one’s grip upon the world.

Existential psychology complements these philosophical insights by demonstrating how existential disconnection manifests in lived experience. Rollo May’s accounts of inauthenticity, Frankl’s notion of the existential vacuum, and Yalom’s analysis of ultimate concerns all underscore the psychological reality of individuals who feel detached from purpose, value, or selfhood. These perspectives show that existential boredom is not merely a theoretical abstraction but a recognisable experiential and clinical phenomenon. They also help situate existential boredom within a broader spectrum of human affect, distinguishing it from forms of boredom associated with simple under-stimulation or monotony.

Taken together, these diverse traditions point to existential boredom as a multidimensional phenomenon (

Figure 1) involving:

The synthesis of these elements establishes existential boredom as a distinct mode of disconnection in which the subject’s world loses its meaningful contours, not due to external monotony but due to a disruption in the subject–world relation itself. This integrated understanding avoids reducing boredom to a single causal mechanism and instead situates it at the intersection of ontology, psychology, and phenomenology.

By recognising the interplay between these dimensions, the theory gains conceptual clarity and specificity. Existential boredom is neither a mere emotional fluctuation nor a universal explanation for all forms of boredom. Rather, it constitutes a particular structure of lived experience characterised by a temporary suspension of meaningful attunement. The theoretical pluralism that underpins the framework is therefore not a weakness but a reflection of the phenomenon’s complexity. Through this critical synthesis, the theory is positioned as a coherent and rigorous account of a unique form of existential disconnection with implications for philosophical anthropology, clinical practice, and the understanding of meaning in human life.

The distinctions established above allow for a more precise engagement with Heidegger’s analysis, particularly regarding the relationship between profound boredom and Unheimlichkeit.

3.4. Heidegger, Unheimlichkeit, and Existential Boredom

As previously distinguished, although existential boredom shares certain structural affinities with Heidegger’s analyses of Langeweile and Unheimlichkeit, it is important to delineate clearly the differences between these phenomena in order to avoid conceptual conflation. Heidegger’s treatment of boredom, especially in the 1929–1930 lectures (The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics), describes a progressive deepening of the mood in which the world loses its capacity to hold us in meaningful involvement. In the first and second forms of boredom, this withdrawal is situational and contingent (“being bored by…” or “being bored with…”). Only in the third and deepest form does boredom reveal a fundamental suspension of Bedeutsamkeit—the meaningfulness that ordinarily structures our being-in-the-world. In this condition, time itself becomes distended; the present loses its grip, and the world’s usual networks of significance fade into a grey indifference. Heidegger emphasises that this profound boredom is not primarily a psychological discomfort but an ontological disclosure: it momentarily unveils the temporal structure of Dasein. Unheimlichkeit, in contrast, is not a mood of withdrawal but a fundamental condition of existential uncanniness. It describes the experience in which Dasein discovers that it is “not-being-at-home” in the familiar world, recognising itself as thrown, finite, and lacking any ultimate ground. While boredom can disclose this uncanniness indirectly by dismantling everyday involvement, Unheimlichkeit is the deeper ontological structure that underlies anxiety, resoluteness, and the call of conscience. It exposes Dasein’s existential groundlessness rather than the temporary loss of worldly appeal. Thus, although deep boredom and uncanniness can overlap, they are not identical. The concept of existential boredom developed in this article intersects with Heidegger’s account insofar as both involve a suspension of significance and a contraction of the meaningful horizon. However, existential boredom, as formulated here, is deliberately more modest in scope: it is not an ontological disclosure but a phenomenological and axiological condition in which one’s field of lived possibilities collapses or becomes inert. Its defining features are affective constriction, impaired teleological projection, and the sense that meaningful action is temporarily out of reach. Unlike Unheimlichkeit, it does not reveal the metaphysical structure of existence; unlike Heideggerian profound boredom, it does not claim to expose temporality in its essence. Rather, it describes a lived disruption in the motivational architecture that ordinarily animates engagement with the world. This distinction is crucial for two reasons. First, it avoids reducing boredom to a mere echo of Heidegger’s ontology, thereby preserving the autonomy of boredom as a mood with its own structure and phenomenological texture. Yet distancing existential boredom from Heideggerian ontological disclosure does not imply that the state lacks any revelatory dimension. What it does not reveal metaphysically, it often reveals experientially: the erosion of meaningful attunement becomes affectively explicit. This is not an unveiling of Being, but a phenomenological awareness of the collapse of one’s lived orientation. Such awareness exposes the fragility of one’s existential footing and can therefore open a space—however minimal—for reorientation. In this more modest sense, existential boredom retains a transformative potential that does not depend on Heidegger’s more radical account of Unheimlichkeit. Second, it clarifies that existential boredom is not a metaphysical verdict on the world’s meaninglessness, but a situated experience that arises when one’s interpretative horizon and practical orientation lose coherence. While Heidegger’s analyses provide a conceptual scaffold for understanding the withdrawal of significance, the theory advanced here reframes this withdrawal in terms of lived value and possibility rather than ontological homelessness. Existential boredom thus occupies a middle ground: it is deeper than ordinary situational boredom but less radical than Unheimlichkeit or the fully ontological disruptions Heidegger analyses.

The present theory therefore diverges from Heidegger by reframing the suspension of significance not as an ontological disclosure but as a situated, affective, and axiological disturbance within everyday existence. What this approach contributes beyond Heidegger is a more fine-grained account of how temporal, embodied, and evaluative structures can weaken without necessarily revealing the metaphysical groundlessness of Dasein, thereby allowing existential boredom to be analysed as a distinct and autonomous phenomenon.

4. The Depth of Boredom: A Phenomenological Analysis

As clarified earlier, existential boredom is distinct from apathy or anhedonia: the affective withdrawal described here does not signify a loss of desire, but a disruption in meaningful attunement. Existential boredom is not a simple emotional disturbance but a distinct mode of disclosure in which the meaningful organisation of experience becomes suspended. While situational boredom arises from monotony or insufficient stimulation, existential boredom reflects a deeper disconnection: the world continues to appear, yet it no longer resonates with the subject. In this state, objects, tasks, and relationships lose their familiar significance, revealing a thinning of Bedeutsamkeit, the background meaningfulness that ordinarily structures being-in-the-world. What characterises this form of boredom is not merely a lack of interest but an affective withdrawal of relevance, as if the world were present yet affectively inaccessible.

This suspension of significance is intimately tied to an alteration in temporal experience. Instead of the ordinary temporal flow, in which the future unfolds as a horizon of possibilities, existential boredom produces a sense of temporal stagnation. Time does not simply slow down; it loses direction. The present becomes heavy and inert, the future seems closed or unreachable, and the past detaches from ongoing concerns. The subject finds themselves unable to project meaningfully toward possibilities, revealing that existential boredom is less a reaction to external circumstances than a failure of temporal intentionality. It discloses the extent to which one’s engagement with the world depends on an underlying, often unnoticed, sense of purpose.

A parallel collapse occurs in the axiological domain. In existential boredom, the values that ordinarily motivate action momentarily lose their force. Activities that once carried meaning appear indifferent; projects that once guided behaviour no longer exert their authority. This is not a form of nihilism but a temporary flattening of the evaluative landscape. The individual retains the capacity to act but lacks the ability to care. In this way, existential boredom exposes the fragility of value-commitments and the degree to which human life depends on their continuous vitality.

The experience also manifests bodily. Drawing on Merleau-Ponty’s notion of the body as the centre of practical engagement, existential boredom can be understood as a weakening of embodied intentionality. Movements feel heavy, gestures lose spontaneity, and the body no longer “reaches out” to the world with its usual readiness-to-act. Perceptual experience becomes flattened and affectively neutral, as though the body were no longer attuned to the solicitations of the environment. This bodily attenuation reinforces the sense of disconnection, revealing that existential boredom is not merely cognitive or emotional but an embodied phenomenon.

Imagination, too, is affected. Under ordinary conditions, imagination opens a space of possibilities, allowing the individual to project themselves beyond the present. In existential boredom, this projective dimension contracts. The subject struggles to envisage meaningful futures or alternative courses of action; possibilities appear muted, distant, or inaccessible. This constriction of the imaginative horizon intensifies the stagnation of temporal experience and the collapse of value, contributing to the pervasive sense of being unable to “move” in an existential sense.

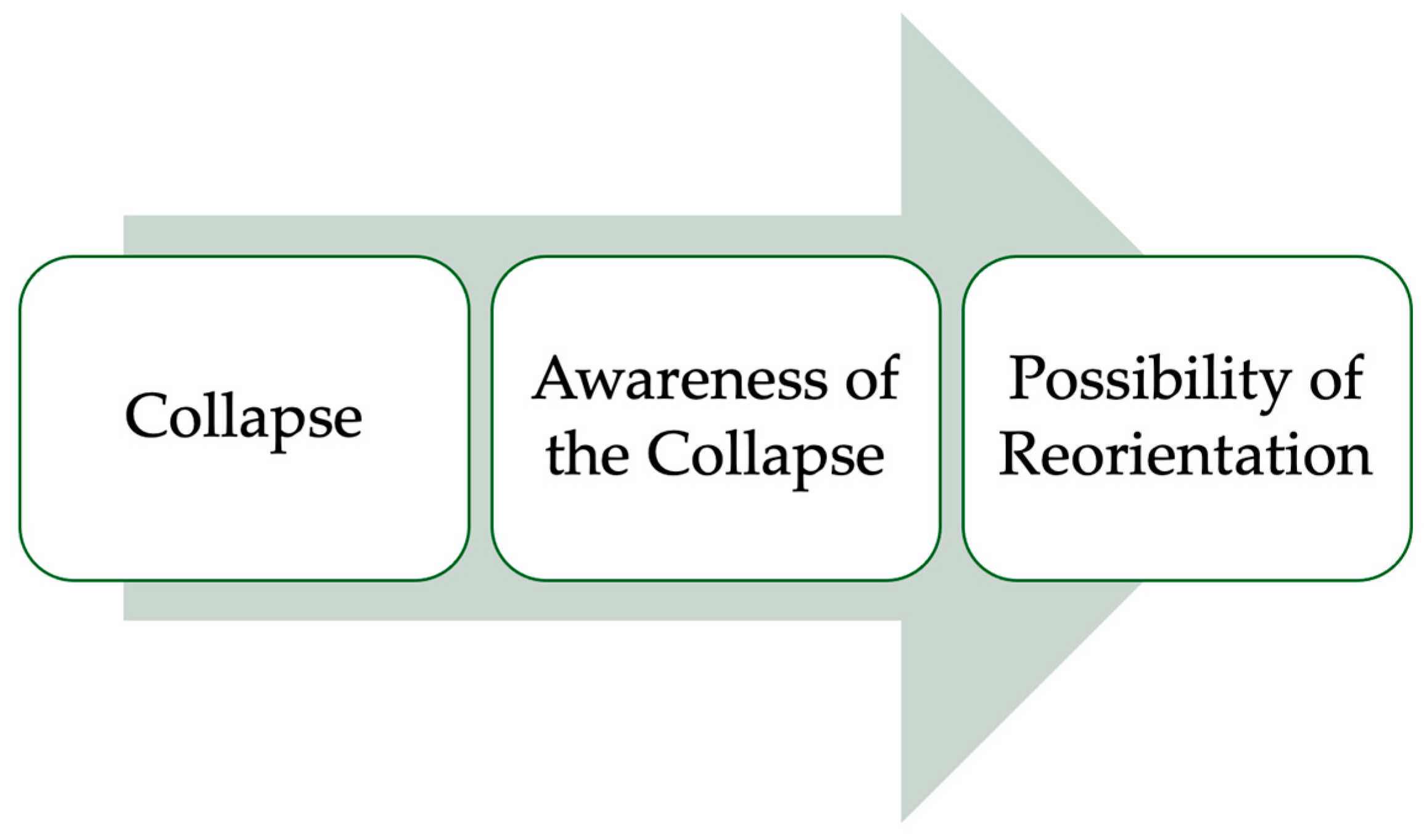

Yet this collapse does not conclude the analysis; it initiates it (

Figure 2). What is first lived as stagnation can become experientially available as stagnation. In other words, the withdrawal of temporal direction, embodied attunement, and axiological grip can give rise to a second-order awareness of their suspension. This shift—from suffering the collapse to recognising the collapse—constitutes the phenomenological hinge through which existential boredom becomes more than a deficit. Once the subject becomes aware of the disturbance itself, boredom may function as a threshold for reflection, a moment in which the erosion of meaning is no longer merely endured but apprehended. This emergent awareness prepares the ground for reorientation by disclosing the need for renewed existential grounding.

Taken together, these dimensions show that existential boredom is a liminal state situated between disengagement and potential transformation. This dynamic can be understood as a form of negative revelation: the structures of meaning become visible precisely at the moment of their suspension. Rather than revealing a positive content, existential boredom exposes an insufficiency—an affective insight that one’s current orientation no longer sustains a viable horizon of significance. This “insight of insufficiency” is not yet a transformation, but it renders transformation thinkable by making the limits of one’s existential position experientially explicit. It is deeper than ordinary boredom but does not amount to a full existential breakdown. Instead, it reveals, through their suspension, the structures that ordinarily sustain meaning: temporal direction, value-commitment, embodied attunement, and imaginative projection. By making these structures visible through their temporary collapse, existential boredom serves as a phenomenological indicator of existential disconnection. It marks a threshold at which the subject becomes aware—however vaguely—of an interruption in their capacity to inhabit the world meaningfully, thereby preparing the ground for examining the socio-cultural conditions that contribute to the emergence of this phenomenon.

In this sense, existential boredom yields an emergent insight: the felt recognition that one’s habitual structures of meaning have lost their orienting power. This does not impose a new direction but opens the threshold of reorientation by rendering the need for renewed engagement affectively palpable. The reflective potential of this state lies precisely in its capacity to disclose the gap between mere activity and meaningful involvement, inviting the subject to reconsider how they inhabit their world.

5. Contemporary Context and the Phenomenological Emergence of Existential Boredom

Contemporary society is marked by an unprecedented saturation of stimuli. The continuous flow of digital information, the acceleration of communication, and the cultural premium placed on constant availability create a mode of life in which attention is fragmented and experiential depth is increasingly rare. Although this environment appears to offer limitless engagement, it often produces a paradoxical effect: the erosion of the very conditions that make meaningful involvement possible. In such a context, existential boredom arises not as a lack of activity, but as a disruption of one’s capacity to inhabit experience with significance.

This socio-cultural landscape fosters a form of experiential superficiality in which individuals remain constantly connected yet existentially unanchored. The proliferation of fast gratification—scrolling, notifications, on-demand entertainment—stimulates without grounding, offering continual occupation but rarely resonance. The result is a diminished capacity for sustained reflection, a weakening of existential orientation, and a subtle but pervasive sense of estrangement from one’s own lived experience. Phenomenologically, this manifests as an attenuation of world-disclosure: the world appears available, yet resistant to meaningful attunement.

Within this broader condition, existential boredom emerges as an affective signal of disconnection. Unlike situational boredom, which arises from monotony or under-stimulation, existential boredom surfaces when the frameworks through which the subject interprets experience lose their motivational force. The individual perceives a growing gap between the intensity of external stimuli and the diminishing ability to find depth, coherence, or purpose within them. This widening discrepancy often generates an emergent insight into the inadequacy of one’s current existential orientation, subtly marking a threshold of possible reorientation. This produces an affective state marked by restlessness, dissatisfaction, and a sense of “inner stagnation,” even amidst external activity.

Such boredom is experienced as a discomfort that cannot be resolved by additional stimulation. It functions instead as a phenomenological awakening: a moment in which the superficiality of habitual routines becomes perceptible, and the absence of authentic engagement is affectively disclosed. Far from being merely unpleasant, this form of boredom carries diagnostic value. It reveals that one’s existential orientation—toward values, relationships, projects, or forms of self-understanding—has become weakened or obscured.

In this sense, existential boredom is not an epiphenomenon of modern distraction but a structural response to it. It surfaces when the subject recognises, however vaguely, that their current mode of life no longer affords a meaningful horizon of possibilities. Thus, the contemporary social context not only amplifies this phenomenon but also provides the very conditions under which existential boredom becomes both more prevalent and more perceptible.

Emerging at the intersection between socio-cultural acceleration and the phenomenological recession of meaning, existential boredom operates as a summons to reorientation. It invites the subject to confront the discrepancy between surface-level engagement and deeper existential needs. As such, it is best understood not purely as an affective deficiency but as a reflective threshold—an opening through which the individual becomes capable of recognising the need for renewed authenticity, purpose, and existential grounding.

Given these distinctions, the existential form of boredom addressed here requires a different mode of reorientation.

6. Overcoming Boredom

Given the conceptual distinctions previously drawn, overcoming existential boredom cannot be reduced to increasing stimulation but requires a reorientation within a contracted horizon of meaning. To overcome boredom, it is fundamental for individuals to seek to reconnect with the elements that truly give meaning to their lives. This involves a journey of self-discovery and reconnection with essential values, genuine relationships, passions, and spiritual pursuits that resonate with their deepest essence. The aim of this section is not to prescribe normative guidance but to illustrate how various philosophical and contemplative traditions conceptualise reorientation when existential disconnection occurs.

One of the first steps to overcoming boredom is the practice of deceleration. In a world dominated by a culture of haste and immediacy, it is crucial to carve out moments to slow down and appreciate the small details of life. This can involve simple activities such as walking in nature, praying, reflecting, meditating, practicing physical exercises, or simply dedicating time to being present in the moment.

Furthermore, cultivating mindfulness is essential for overcoming boredom. Mindfulness involves being consciously aware and attentive to the present moment, without judgments or distractions. Practicing mindfulness allows individuals to be more present in their daily experiences, finding beauty and meaning even in the simplest activities.

Seeking moments of deep reflection and contemplation, individuals can embark on a journey of self-exploration and personal growth. These moments of introspection allow them to connect with their true needs, desires, and aspirations, helping them find a deeper sense of purpose and meaning in life.

The original concepts of mindfulness can be found in Buddhist psychology, especially in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta [

45], and the subsequently created Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta [

46,

47,

48]. In this context, many refer to mindfulness as “the heart of Buddhist meditation”. And indeed, Buddhism, perhaps more than other traditions, has extensive literature on the state of mindfulness, which is a fundamental part of the teachings of that religion. But does this somehow mean that mindfulness is a Buddhist concept? No! Quite the contrary… The essence of mindfulness is also at the core of other ancient religions:

- (1)

In Hinduism and Rāja Yoga, the branches of practice called Dhāraṇā [

49,

50], dhyāna [

51,

52,

53] and Samādhi [

54];

- (2)

In Islam and Sufism, in Dhikr [

55], also a state of high concentration;

- (3)

In Christianity, in the “prayer of silence” or hesychasm [

56,

57] (Hesychia, in Greek);

- (4)

Perhaps even in altered states of consciousness induced by the consumption of ayahuasca, ayuasca or daime from religious rites based on traditional ceremonies of peoples in countries such as Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, and Brazil, and still by at least 72 different indigenous tribes of the Amazon [

58,

59];

- (5)

In Judaism, in Kavaná [

60].

By reconnecting with their authentic values, meaningful relationships, passions, and spiritual quests, individuals can transcend boredom and find a renewed sense of vitality and fulfilment. This journey of reconnecting with oneself and with the world around them is essential for a more authentic, meaningful, and rewarding life. Such practices are not presented as mere techniques of distraction, but as existential reorientations in the Franklian sense of rediscovering meaning [

38] and in the Mayan sense of reclaiming authentic selfhood [

35]. In this regard, overcoming boredom is not primarily a clinical objective, but an ethical-existential task.

The purpose of this brief comparative overview is not to offer an exhaustive survey of contemplative traditions but merely to contextualise mindfulness as a cross-cultural mode of existential reorientation rather than a culturally isolated technique.

7. Implications for Philosophy, Today’s Psychology and Psychiatry, and Contemporary Life

Understanding existential boredom as a form of experiential disconnection yields significant implications for philosophy, contemporary psychology, and modern psychiatric thought. Philosophically, this framework emphasises boredom as an affective disclosure of the structures that enable meaningful existence. By making visible the suspension of temporal direction, value-commitment, embodied attunement, and imaginative projection, existential boredom becomes a privileged site for examining the fragility of human meaning-making and the conditions under which authentic self-realisation becomes possible.

Within today’s psychological and psychiatric discourse, this conceptualisation challenges approaches that treat boredom primarily as a behavioural deficit, an attentional failure, or a symptom reducible to cognitive under-stimulation (

Figure 3). Instead, existential boredom reveals a deeper form of disorientation in which individuals lose access to the evaluative and projective structures that ordinarily orient their lives. This perspective resonates with existential therapeutic approaches and complements contemporary psychiatric interest in disturbances of meaning, agency, and selfhood. It suggests that the mere addition of stimulation or behavioural activation fails to address the underlying issue: the collapse of lived significance. As such, existential boredom may serve as a clinically meaningful indicator of disruptions in purpose, coherence, and identity, expanding the scope of how boredom is understood within mental health contexts. It is important to emphasise that existential boredom is not presented here as a pathological entity or clinical construct. Rather, it is understood as a normative, though significant, form of experiential disruption that may occur independently of psychiatric conditions or mood disorders.

Culturally, the theory illuminates the paradox of contemporary life: a world characterised by hyper-stimulation, accelerated communication, and continuous availability that nonetheless fosters pervasive experiences of inner emptiness and purposelessness. Existential boredom exposes the mismatch between the rapid pace of modern environments and the slower, integrative processes through which meaning is constituted. It therefore provides a powerful conceptual tool for analysing phenomena such as digital saturation, attention fragmentation, the rise of mood disorders linked to disconnection, and the contemporary sense of existential drift reported across sociological and psychiatric studies.

Finally, existential boredom can be understood as a threshold experience. Although affectively unsettling, it opens a reflective space in which individuals may recognise that their current orientations no longer adequately sustain a meaningful life. In this sense, boredom possesses a transformative potential: it may catalyse a re-evaluation of priorities, a reorganisation of values, or a deeper engagement with questions of authenticity, purpose, and self-understanding. Rather than interpreting boredom merely as a psychological nuisance or psychiatric symptom, this framework reframes it as an affective invitation to reorient one’s existence toward greater coherence and existential depth.

The Boredom Theory as a Sign of Existential Disconnection not only offers a profound understanding of the human experience but also holds significant practical implications across various fields (

Figure 4), from social to existential. Some of these implications are:

In summary, the Boredom Theory as a Sign of Existential Disconnection transcends disciplinary boundaries and offers a holistic approach to understanding the complexity of the human experience. Its practical implications have the potential to inspire significant changes in our individual lives and in society as a whole.

8. Conclusions

The originality of this work lies in articulating existential boredom as a distinct phenomenological structure—one that integrates temporal, axiological, embodied, and imaginative dimensions—thereby offering a unified conceptual framework that neither collapses into Heidegger’s ontology nor into Frankl’s therapeutic existentialism.

This article has examined existential boredom as a distinctive mode of disclosure in which the structures that ordinarily sustain meaningful engagement become suspended. By synthesising contributions from existential philosophy, phenomenology, and contemporary perspectives from today’s psychology and psychiatry, the study argued that boredom is not merely a response to monotony but a revealing affect that exposes disruptions in temporal projection, value orientation, embodied intentionality, and imaginative openness. Through this lens, existential boredom emerges as a diagnostic marker of diminished attunement to the world rather than a superficial emotional fluctuation.

Situating this phenomenon within the dynamics of contemporary life further emphasised its relevance. Hyper-stimulation, accelerated communication, and fragmented attention create conditions in which individuals may remain ceaselessly occupied yet existentially unanchored. Against this backdrop, existential boredom acquires both explanatory and critical power: it highlights a structural mismatch between the rhythms of modern environments and the deeper processes by which meaning is constituted, maintained, and renewed. This insight supports recent developments in psychological and psychiatric research that recognise disturbances of meaning, coherence, and self-orientation as central components of mental suffering.

At the same time, existential boredom possesses a transformative dimension. Although often experienced as discomfort or stagnation, it also marks a threshold where the inadequacy of one’s current existential orientation becomes affectively perceptible. By making visible the suspension of meaningful possibilities, boredom invites a re-evaluation of commitments, priorities, and interpretive frameworks. It therefore offers an opportunity for renewed authenticity and existential recalibration.

Understanding boredom in this way deepens philosophical inquiry, enriches today’s psychological and psychiatric approaches to human distress, and provides a conceptual tool for interpreting the challenges of contemporary existence. Recognising its diagnostic and transformative potential allows us to appreciate boredom not as a trivial inconvenience but as an affective signal pointing toward the need for renewed engagement with self, world, and value.

In direct response to the research question, this article argues that boredom can function as a phenomenological indicator of existential disconnection precisely when a temporary suspension of temporal direction, axiological orientation, embodied attunement, and imaginative projection becomes experientially manifest.

This indicator is not universal, nor does it imply an ontological diagnosis; its significance emerges only under conditions in which the subject’s lived horizon of possibilities contracts in a manner that can be affectively recognised.

This article also clarified why the term boredom remains appropriate for this phenomenon. Although existential boredom differs from ordinary boredom in depth and locus, both share the core affective structure that defines the boredom genus, ensuring terminological coherence.

Importantly, this suspended condition is not merely privative. By rendering the withdrawal of meaning experientially explicit, existential boredom generates an emergent insight into the inadequacy of one’s current manner of inhabiting the world. This does not constitute transformation in itself, but it marks the threshold of possible reorientation, where renewed commitments or forms of authenticity can begin to take shape. The reflective potential of existential boredom therefore lies not in any intrinsic function or productivity but in its capacity to expose the need for existential recalibration. In this respect, the phenomenon serves as both a diagnostic marker of diminished attunement and a liminal space from which renewed forms of meaning-making can emerge.

9. Limitations and Future Directions

This study is primarily conceptual and phenomenological, and therefore does not claim empirical generalisability across all forms of boredom. Existential boredom, as defined here, concerns only a specific configuration of experiential disconnection and should not be conflated with cognitive under-stimulation, psychiatric syndromes, or culturally mediated expressions of dissatisfaction. Future research could explore whether the core dimensions identified—temporal contraction, loss of evaluative grip, diminished embodied attunement, and reduced imaginative projection—can be operationalised and examined empirically in clinical, psychological, or sociological settings.

Future empirical studies could examine whether the phenomenological markers identified here—such as temporal stagnation, diminished evaluative resonance, and reduced embodied readiness-to-act—can be measured in laboratory or clinical settings, potentially clarifying the boundary between existential boredom and related affective states.