1. Introduction

As a significant form of contemporary mass art, video games have the potential to transform the relationship between players and the real world through their unique interactivity and immersive qualities [

1]. In the context of cultural globalization, they have also attained a distinct cultural status. This raises the question: how should people perceive the relationship between games and humanity? Over two centuries ago, in

On the Aesthetic Education of Man, Schiller [

2] argued that man is only fully human when he plays. In this view, games seem to serve as a bridge to freedom. Yet, in the present day—more than two hundred years later, in an era of rapid technological advancement where the definition of “games” has become increasingly diverse—this relationship warrants reevaluation. Do video games truly make players freer, or do they, instead, subject them to manipulation by algorithms, leading them unknowingly into a frenzy of control?

In reality, every action in a video game—whether deciding when to attack, which item to pick up, or which path to take—appears to be a free choice made by the player. However, these decisions are subtly shaped and controlled by game design and algorithmic structures. From this standpoint, video games have already become instruments of biopower [

1]. Each action performed by the player is reduced to a quantifiable data point within an activity log. Rather than fostering freedom, the player is ensnared in a state of encirclement—experiencing an erosion of subjectivity under the guise of entertainment. As Shinkle [

3] has pointed out, flow, often considered the hallmark of exemplary game design, paradoxically reveals the diminishing of the player’s subjectivity.

Immersion often operates as a double-edged sword. On one hand, it enables players to engage with a world distinct from reality; on the other, it acclimates them to being controlled by covert yet sophisticated power structures within the virtual world. Through continuous reinforcement of affirmative feedback, players gradually become desensitized, ultimately reduced to “docile bodies” [

4]. However, within the seemingly impenetrable structure of immersive experience, there are moments that disrupt the virtual illusion, compelling players to re-engage with reality—specifically, the involuntary interruptions of immersion caused by experiences of suffering. These disruptions violently fracture the virtual world, opening a conduit to the real. In this abrupt disengagement, players momentarily withdraw from the virtual realm and briefly glimpse the underlying power structures that govern their experience.

This article will first explore suffering as a potential site of resistance against biopolitical control, drawing on Max Scheler’s phenomenology of emotion. In this study, “suffering” specifically refers to a profound spiritual or psychological pain arising from systemic forces (e.g., social, economic, political, or game-imposed systems). Rather than focusing on physical suffering, this paper concentrates on the experience of suffering that emerges within structures of biopower, where individuals are subjected to invisible yet pervasive forms of control. It will then examine

Black Myth: Wukong [

5] as a paradigmatic case in which both gameplay and narrative are structured around suffering. Through this analysis, the study will demonstrate how video games, by engaging players in suffering experiences, facilitate a shift from passivity to agency, fostering an emergent awareness of resistance to oppressive power structures. Video games, with their immersive and interactive nature, have transformed the way people engage with artistic works: they dissolve the aesthetic distance, enabling an unprecedented level of participation in art. In other words, video games allow players to encounter and solve problems as engaged actors, rather than passive observers [

6]. This shift aligns with Benjamin’s [

7] analysis of mass art in the age of mechanical reproduction—where art, having lost its “aura”, no longer relies on ritualistic value but increasingly assumes a political function. It is precisely for this reason that video games, through the experience of suffering, have the potential to provoke critical reflection among players, revealing their role as a medium of resistance within the biopolitical framework.

2. Suffering as an Opportunity for Resistance Against Biopolitics

For a long time, suffering has been regarded as a meaningless condition and, to some extent, a manifestation of the loss of subjectivity. The ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus [

8], in his conception of pleasure, argued that suffering is something humans should strive to avoid, as it lacks intrinsic value. According to Epicurus, suffering gains meaning only when enduring it to some extent leads to a greater degree of pleasure. On this basis, he advocated for achieving a state of mental and physical tranquility through precise rational calculation. This perspective, at its core, reflects a passive approach—one that treats suffering as an object to be avoided rather than engaged with. As a result, when suffering arises, individuals are left with no recourse but to endure it passively.

The renowned German phenomenologist Max Scheler regards suffering as an essential path toward spiritual transcendence in human existence, which stands in contrast to Epicurus’s view that suffering can be eliminated through rational evaluation and moderation. For Scheler [

9], suffering represents a form of sacrifice—a voluntary renunciation of lower values in the pursuit of higher ones. These higher values, in his philosophical system, belong to the metaphysical realm and are apprehended through intuitive and emotional insight rather than rational calculation. Scheler [

9] argues that individuals can adopt different volitional attitudes toward the same experience of suffering—they may bear, endure, undergo, or even enjoy it. According to Scheler [

10], emotions can be categorized into feeling functions and emotional acts, as well as feeling states: feeling functions and emotional acts are directed toward values, whereas feeling states arise as a result of values. Different intentional orientations thus lead to distinct outcomes, highlighting the vast realm of meaning and freedom inherent in human emotional life. When confronted with suffering, individuals become acutely aware of their own limitations. However, this does not imply a mere retreat of the subject into the background. On the contrary, depending on their spiritual will, individuals can, through acts of spiritual personality, ascribe a meaning to suffering that transcends its immediate experience. It is precisely in this process that suffering creates the possibility for the reconstitution of subjectivity.

However, this does not mean that Scheler advocates actively seeking or glorifying suffering. On the contrary, he argues that the endurance of suffering is ultimately meaningful only when it yields compensatory feelings of bliss and enables individuals to transcend suffering in an upward trajectory. After all, it is as difficult for humans to relinquish happiness and joy as it is to abandon existence itself [

9]. Scheler [

9] classifies pain into two distinct types. The first arises when an individual, perceiving resistance from the whole, invests less energy in resisting and maintaining their existence—this is “the pain of being powerless”. If understood in a non-metaphysical, broadly experiential sense, this form of suffering refers to the pain an individual feels when confronted with an overwhelming totality—such as society, institutional systems, or natural forces—and experiences complete suppression and powerlessness to resist. For instance, an assembly line worker engaged in perpetual recurrence of compartmentalized motions may achieve cognizance of labor alienation, yet remain structurally immobilized—aware that job termination would jeopardize material subsistence conditions. The second type, by contrast, occurs when an individual exhibits extraordinary initiative against the whole, but the rigidity of the whole’s structure strongly suppresses the part that seeks to grow in power and scale—this is “the pain of growth” or “the pain of becoming”. For example, an artist working under an authoritarian regime may persist in creating works that expose social problems, fully aware that they may be censored, criticized, or even punished. The suffering he endures—loneliness, anxiety, and marginalization—is intense, yet it is a form of pain marked by agency and transcendence. Through resistance, he experiences the power of his own existence, and his suffering thus takes on the meaning of growth and spiritual elevation. In Scheler’s view, the former is the more common form of suffering, whereas the latter is the nobler one, serving as a harbinger of life’s transcendence. He disparages the former while exalting the latter [

9]. In this sense, suffering is not celebrated for its own sake; it is valuable only insofar as it reveals the structure of oppression and creates opportunities for conscious engagement and resistance. The pain of growth is intimately linked to the higher development of life. Without suffering, there can be no genuine expansion of life, and the ultimate outcome of life’s growth is true love and bliss. Suffering, as an unavoidable condition of life’s evolution, possesses an ontological significance. All consciousness has its foundation in suffering, and all higher levels of consciousness have their foundation in increased suffering—over and against original spontaneous movements [

11]. It is through this process of suffering that humans develop the capacity for precise objectification of the world, as consciousness itself is shaped by the experience of suffering. In the process of objectifying the world, individuals experience an inherent sense of separation from it, thereby plunging into a state of existential void. This experience is often accompanied by profound fear and resistance, creating an obstacle to the human will to live. In response, humans engage in the highest form of spiritual asceticism. Scheler [

11] employs two vivid metaphors to illustrate human attitudes toward reality: the existence of animals is “embodied philistinism”; humans, by contrast, ought to embody the spirit of an “eternal Faust”. Unlike animals, which lack the capacity to say “no” to reality, humans are perpetual adversaries of mere reality. They can never exist in passive harmony with the world around them; instead, they are constantly driven by an insatiable yearning to transcend the confines of “this time, this place, this thing”—including the reality of their own being.

Scheler’s [

10] analysis of suffering is grounded in his theory of emotional depth levels, which categorizes emotional experiences into four hierarchical strata: sensible feelings, vital feelings, pure psychic feelings, and spiritual feelings. While the first two are shared with animals, the latter two are distinctly human, as they possess intentional and cognitive dimensions [

9]. The presence of psychic and spiritual feelings suggests that the human mind has the potential either to ascend toward personal fulfillment or to descend into self-degradation. As Scheler [

9] asserts, “All suffering and all pain are, according to a metaphysical and most formal meaning, a sacrifice of the part for the whole and of (relatively) lower values for higher values”. Through the lens of his interpretation of sacrifice, the nature of suffering becomes clearer: the more one achieves fulfillment at deeper emotional levels, the more freely and effortlessly one can endure suffering at lower levels. Conversely, an excessive indulgence in pleasure at the lower levels renders the deeper levels increasingly susceptible to suffering. This perspective also sheds light on a paradox of modernity: despite the exponential proliferation of pleasure-inducing means in advanced industrial society, human suffering has not diminished but rather intensified. The expansion of the state, the growing complexity of social organizations, the increasing specialization of labor, and the advancement of technology have not led to a steady increase in individual happiness; instead, they have exacerbated suffering [

9].

In a sense, it is precisely the unchecked pursuit of instrumental rationality in advanced industrial society that reduces human life to a mere object of management—what Agamben [

12] terms “bare life”. The figure of homo sacer epitomizes this condition. Originating from ancient Roman law, homo sacer initially referred to an individual condemned for a crime—one who could not be sacrificed in religious rites but could be killed with impunity. According to Agamben, in modern democratic states, ordinary citizens may at any moment be reduced to homo sacer through the invocation of a state of exception. Homo sacer is paradoxically included within the political order precisely by being excluded from it, existing simultaneously inside and outside the law, with no legal protection over their life. Homo sacer and the sovereign occupy opposing poles: to the sovereign, all individuals are potential homo sacer; to homo sacer, all individuals act with the authority of a sovereign [

12].

In advanced industrial society, individuals’ needs and desires are preconfigured by the machinery of the system. While such a society ostensibly promises ever-increasing comfort, in reality, the scope of imaginable life remains confined within the boundaries of the existing social structure [

13]. This critique aligns with Scheler’s argument that suffering outweighs pleasure in modern society precisely because individuals are restricted to seeking pleasure at lower levels of fulfillment. Likewise, Agamben [

12] argues that modern society, from its inception, has sought to normalize bare life as a mode of existence. The fundamental paradox of modern democracy lies in this very condition: the pursuit of happiness and freedom is constrained within the realm of bare life—a realm that, in the end, signifies submission to power.

It is worth contemplating: were technology and means of production not originally created to enhance human happiness? Why is it, then, that despite the relentless pursuit of pleasure, people ultimately encounter suffering? Within this paradox, the experience of suffering becomes both a direct response to invisible oppression and a profound inquiry into the meaning of existence. If individuals remain immersed in the illusion of happiness constructed by modern democratic states within the confines of bare life, they fail to recognize that they are already trapped within an invisible cage. Only through suffering can self-awareness emerge, allowing the desire for life to permeate and integrate with the spirit, ultimately merging bios and zoē into a unified form-of-life. It is through this synthesis that the possibility of true happiness arises.

However, in real life, suffering often overwhelms individuals before they have the opportunity to engage in critical reflection. Art, by contrast, provides a mediated distance that facilitates contemplation of suffering. As Jiang [

14] argues, artistic media render suffering intelligible by making it describable, representable, and communicable. In an era where media have become integral to human communication and existence, video games—as a highly immersive contemporary medium—offer a novel mode of perceiving the world. Their most distinctive feature lies in the potential for players to exert influence, to some extent, over the world inhabited by their avatar, with the avatar serving as an extension of the player’s agency. For this reason, Juul [

15] asserts: “…we would have to admit that we thought about how to bring about the unfortunate events. All of which suggests that games are the strongest art form yet for the exploration of tragedy and responsibility.” As a medium, video games not only allow individuals to confront suffering firsthand but also enable them to maintain a reflective distance. This dual capacity deepens one’s understanding of suffering and, in doing so, holds the potential to foster players’ resistance against biopolitical structures.

3. The Experience of Suffering in Black Myth: Wukong

What kind of path of resistance does Black Myth: Wukong ultimately propose? It is a path that becomes attainable only when the player attains self-awareness through the experience of suffering, thereby integrating the will to live with the spirit.

The release of Black Myth: Wukong marks a significant milestone in the history of Chinese game development. First, it is widely regarded as China’s first true AAA game. Second, as of 31 December 2024, the game has achieved global sales of 28 million copies. Moreover, at The Game Awards (TGA) 2024, it received four nominations: Game of the Year, Best Action Game, Best Art Direction, and Best Game Direction. These accomplishments illustrate that the game’s core appeal transcends national boundaries, capturing the attention of players worldwide.

The game is a reinterpretation of Journey to the West, one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, developed and adapted by Game Science. Its narrative unfolds in a world where the gods of the Heavenly Court exploit faith as a means to refine humans, demons, and even disobedient deities into elixirs, absorbing their Will to attain immortality. Within this framework, the pilgrimage to the West is exposed as nothing more than a façade—an orchestrated scheme by the Heavenly Court to contain Sun Wukong, a being of immense power and rebellious spirit, within their established order. From a biopolitical perspective, the gods of the Heavenly Court, driven by their pursuit of eternal life, assume the role of sovereigns, while all others—humans, demons, deities, and Buddhas—are reduced to homo sacer.

Thus, donning the Golden Hoop and attaining the title of Victorious Fighting Buddha symbolizes Sun Wukong’s submission to the authority of the Heavenly Court, whereas renouncing his Buddhahood and returning to Mount Huaguo represents an act of resistance.

Black Myth: Wukong begins with Sun Wukong seeing through the schemes of the Heavenly Court and choosing to return to Mount Huaguo, only to be annihilated by Erlang, the Sacred Divinity, along with the celestial troops. Following his death, Sun Wukong’s six sense faculties—eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and body—were each distributed among five demons by Erlang, while he himself retained Wukong’s mind. In Buddhist thought, these six sense faculties (ṣaḍ indriyāṇi) serve as the mediums through which humans perceive the external world. As stated in the

Śūraṅgama Sūtra [

16]: “Your present faculties—eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind—are six thieves that steal your spiritual treasures.” Through the six faculties, one perceives the six dusts (ṣaḍ viṣayāḥ), yet such perception is seen as an obstacle to spiritual cultivation, as all afflictions and suffering arise from attachment to them. Thus, Buddhist doctrine emphasizes the purification of the six faculties as a means of transcendence. However, However, the philosophical underpinning of

Black Myth: Wukong stands in direct defiance of this doctrine. When the player-controlled “Destined One” first emerges, the game explicitly states its singular objective through the words of the Old Monkey: to reclaim the six sense faculties and resurrect Sun Wukong (

Figure 1).

This objective clearly signifies a fundamental divergence between Black Myth: Wukong and the original conclusion of Journey to the West, in which enlightenment is achieved through the attainment of Buddhist scriptures. Instead, the game asserts that true humanity is defined by one’s perception of the mundane world—seeing joy, hearing anger, smelling love, tasting contemplation, embodying sorrow, and harboring desires of the mind—all of which are indispensable aspects of existence. This perspective embodies a profound affirmation of natural life.

However, merely emphasizing natural life is insufficient to mount a true resistance against the Heavenly Court within the game. The character of Huang Mei (Yellow Brows) exemplifies this limitation. Although he despises the hypocrisy of the Heavenly Court, he differs from Jin Chanzi, who harbors compassion for the mortal world. Instead, Huang Mei contends that human nature is inherently evil and, if this is the case, argues that all desires should be amplified without restraint. During the player’s battle against the Macaque Chief, Huang Mei, observing from the sidelines, delivers a striking monologue [

5]: “I remember what Buddha said at the Ullambana: ‘All beings suffer ad they heed not the precepts and indulge.’ I say: nonsense! Thou shalt kill, lest feuds instill. Thou shalt snatch, a fair play in a fair match. Thou shalt lust, before all loves into dust. Thou shalt boast, for prestige and legacy it doth host. Thou shalt drink, and drenched unease shall sink. Thou shalt revel, prime year shan’t be spent to settle. Thou shalt dream, to reach in bleak void the sole gleam. Thou shalt indulge, or life is but a scourge!” This passage fully encapsulates Huang Mei’s worldview, which rejects traditional moral constraints and embraces unrestrained desire as the essence of existence. However, his eventual downfall signifies that a life driven purely by unchecked desire, without spiritual guidance, can only lead to indulgence and destruction.

Although the game does not offer explicit textual guidance or explanations, it subtly directs players toward a path that contrasts with Huang Mei’s worldview. However, this path is not immediately apparent; rather, it must be actively contemplated and uncovered through the progression of the gameplay experience.

As the Destined One, the avatar remains silent throughout the game, initially tasked with only one compulsory mission: to collect the six sense faculties and resurrect Sun Wukong. A distinctive feature of the game lies in its design: if the player does not follow the given objective, the game simply does not progress. Therefore, under typical circumstances, players rarely question the goals imposed by the game. However, if the player pauses to consider the question—“Why must I resurrect Sun Wukong?”—they will first experience a profound sense of non-presence, realizing that they exist merely as an instrumental entity within the game’s mechanics. The contradiction between the player’s growing sense of subjectivity and the controlled, repressed avatar constitutes moments of reflection that emerge in digital game design [

17].

Black Myth: Wukong is a high-difficulty action game, where the average player may die multiple times, sometimes dozens, before defeating a boss (a major enemy). Progression in the game involves enduring repeated setbacks and the constraints imposed on the player’s abilities, rather than death itself being the source of suffering. While repeated in-game deaths occur, it is the experience of frustration and limitation that draws the player’s consciousness back to reality, allowing them to pause and perceive how they are being manipulated and constrained by the game system. This reflective awareness marks the onset of the player’s subjectivity awakening [

18].

This gameplay experience is, of course, deeply painful. It forces players to confront their own limitations, prompting them to question not only themselves but also the very objective of the game: “After all this suffering, am I really fighting merely to resurrect Sun Wukong, a figure who holds no personal significance to me? Is any of this truly worthwhile?” However, as the player continuously endures suffering and overcomes their own limitations, the initial sense of non-presence gradually transforms into a sense of presence. It is crucial to note that this sense of presence is not the same as immersion. Rather, it signifies the moment when the player realizes that it is their own spirit, not the predetermined objective imposed by the game, that is propelling the Destined One forward.

How, then, do players overcome their limitations in suffering, transitioning from passive submission to active engagement? Consider, for example, the early-game boss fight against Tiger Vanguard. Based on the author’s first-hand gameplay experience and discussions with peers, and following a phenomenological approach that emphasizes the first-person, lived experience of the phenomenon, initially, when confronted with the overwhelming presence of Tiger Vanguard and the blood pool surrounding him, players may experience elevated heart rate, with each death escalating their frustration and self-doubt. However, as the number of deaths accumulates, players must, in order to succeed, gradually withdraw their consciousness from the game world and into reality, recognizing how the game’s mechanics shape their experience. At this juncture, the seemingly chaotic and oppressive attacks of Tiger Vanguard begin to break down into discernible patterns. For instance, when Tiger Vanguard initiates a long-range charge, experienced players can anticipate his subsequent leap-and-grab attack (

Figure 2). At this stage, the player has not only disengaged from the immersive immediacy of the game, no longer controlled by its intense visuals and sound design, but has also begun to approach the game from an external perspective—analyzing its mechanics, identifying patterns, and applying them with precision. Through this process, players experience both the oppressive forces within the game and their gradual transcendence of personal limitations, resulting in a far deeper psychological and spiritual satisfaction than that found in more casual gaming experiences.

This experience of suffering in gaming is, at its core, a process of sacrificing superficial pleasure in exchange for self-growth and a more profound form of enjoyment. According to Allison et al. [

19], suffering in video games should not be understood as an isolated, fleeting emotion, but rather as a necessary passage within a broader experiential arc. Without this struggle, the pleasure derived from gaming would be significantly diminished, and the medium itself would fail to fulfill its intended purpose.

4. The Awakening of Subjectivity in Black Myth: Wukong

Current discussions on subjectivity in video games generally follow two distinct paths. One perspective asserts that the actions players take within the game world and their capacity to influence it serve as an embodiment of their subjectivity. For example, Vella [

20], in his early research, introduced the concept of “ludic subjectivity”, arguing that players construct a subjective sense of “I-in-the-gameworld” through their interactions with avatars and the game world. In other words, a player’s subjectivity gradually emerges through a series of actions performed within the game world.

However, it is crucial to consider the extent to which this subjectivity is genuinely under the player’s control. In reality, seemingly spontaneous interactions within a game system are often predetermined by its design and governed by underlying algorithms [

21]. In other words, the choices that players perceive as free are, in fact, merely one of the predefined pathways established by the game designers. Some may argue that open-world games like

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild [

22] offer players a wide range of choices that are not directly tied to the main game objective, seemingly reinforcing the notion of player agency. However, this perspective overlooks a critical issue: many of these actions serve primarily as sources of entertainment and lack deeper cultural or humanistic significance (Wang et al. [

23]). Thus, while such actions may momentarily allow players to recognize their own subjectivity, they do not necessarily encourage critical reflection on the extent to which they are being controlled within the game.

Another perspective, however, entirely denies the existence of player subjectivity in video games. Shinkle argues that the widely discussed sense of immersion and presence in video games is, in fact, indicative of the player’s loss of subjectivity. He contends that playing video games entails a Faustian bargain with technology—sacrificing agency in the real world in exchange for agency within the game world. He writes: “Playing a videogame involves a kind of Faustian bargain with the technology, a handing-over of real-world agency in exchange for agency within the gameworld. We exist in reduced form in the gameworld, our sense dulled, our choices and actions limited, and we are bound to the terms of engagement of the interface as a visual system and a material artifact. In exchange, the game offers a different reality, one of spectacular scenography, enhanced abilities, and more or less eternal life” [

3]. However, such a harsh critique of video games is overly reductive, as it is evident that players do not entirely relinquish their subjectivity while engaging with games. Vella, who initially introduced the concept of “ludic subjectivity”, later refined his argument, suggesting that players actually experience two interrelated forms of subjectivity in video games: virtual subjectivity and actual subjectivity. He posits that virtual subjectivity is fundamentally grounded in actual subjectivity, establishing a clear hierarchical relationship between the two [

24]. In other words, assuming a subjective position in the virtual world does not entail the abandonment of one’s actual subjectivity. Rather, the role that players adopt in video games can be understood as a virtual extension of their actual selves.

Neither of these perspectives offers a fully satisfactory answer. Players in video games are neither entirely free nor wholly constrained. The crucial question, then, is under what conditions players can break away from the immersive experience of a game, enter a reflective state, and become aware of their own subjectivity—rather than being passively guided by game design and algorithms. The defining characteristic of video games is their strong sense of immersion and presence. This quality enables players to experience emotional resonance at a level unparalleled by other art forms, yet it is also what causes them to become “lost” in the game world. Paradoxically, however, the experiences of suffering within video games serve to disrupt this immersion, prompting players to step back and reassess their engagement with the game.

As previously discussed, Scheler [

10] argues that human beings possess an active agency in the face of suffering. He regards “the pain of growth” as a more noble form of suffering—one that embodies the individual’s intense struggle against and transcendence of a rigid totality. This understanding directly corresponds to the suffering experienced by players when they confront the systemic and narrative constraints of a game: a suffering born from their simultaneous awareness of powerlessness and their desire to resist and break free. If one remains wholly immersed in the illusion the game provides, merely following the instructions dictated by the system, such subjectivity is merely a false one—because it is, in essence, still governed and controlled.

Indeed, as Shinkle suggests, video games do, to some extent, demand a Faustian exchange: immersion is purchased at the cost of confinement to the narrow frame of the screen, where the player’s entire sensorium becomes absorbed into a virtual world. Yet this paper contends that it is precisely through the pain induced by repeated deaths and failures that players are forced to interrupt their seamless immersion. Such interruptions enable them to recognize that what they are facing is, after all, a game rather than a real world. When players step back to examine their own play experience from the outside—and become aware of the algorithmic forces that shape and constrain them—they begin to attain genuine subjectivity.

According to Scheler’s [

10] theory of emotional depth levels, the more one indulges in superficial pleasure, the more suffering one encounters at the deeper levels of an emotional life. Conversely, by relinquishing surface-level pleasure, one opens the possibility for deeper transcendence. Hence, the experience of suffering in games serves as a crucial moment for the awakening of the player’s subjectivity.

Black Myth: Wukong employs the player’s inevitable suffering through the “Eighty-One Difficulties” as a means of prompting reflection on their existence as the “Destined One” and the nature of the world they inhabit. As the “Destined One”, the player is compelled to embark on a journey to subdue demons and vanquish monsters—not out of personal will, but to fulfill a predetermined objective. Throughout this journey, the player encounters characters such as the Black Bear Demon, Yellow Wind Sage, Yellow Brow, Hundred-Eyed Demon Lord, and Red Boy, gradually uncovering their individual stories and recognizing the hypocrisy of the Heavenly Court.

The second chapter, “Yellow Sand, Desolate Dusk”, offers a profound critique of the hypocrisy embedded within the Heavenly Court system and its power dynamics. This chapter’s narrative space is centered around Yellow Wind Ridge, formerly the domain of the Kingdom of Flowing Sand. According to the game’s text, the Kingdom of Flowing Sand was once a flourishing golden realm where the sound of boiling seas at sunset posed a lethal threat to children. To quell this disaster, the Buddha bestowed the Sunset Drum, which subsequently became a symbol of Buddhist teachings. However, as the number of believers grew, the king, fearing that widespread faith would weaken secular authority, issued an edict banning Buddhism to consolidate his rule. In the aftermath, the Sunset Drum lost its divine function and could summon only insect demons that slaughtered the people, reinforcing the notion that only faith in the Buddha could ensure protection.

In the hidden storyline, the player uncovers that the events were orchestrated by the Western Paradise (Xitian) as part of a carefully crafted belief manipulation mechanism. The core logic behind this system is to maintain a continuous supply of faith by generating unavoidable crises—such as the insect demon massacre—using these calamities to extract the spiritual essence from the believers’ devotion. However, the Western Paradise did not anticipate the intervention of the Rat Demon—The Yellow Wind Sage—who happened to pass through the region and defeated the insect demons, rescued the people of the Kingdom of Flowing Sand, and, as a result, the entire kingdom converted to Yellow Wind Sage’s faith. This unexpected turn of events directly threatened the Western Paradise’s control over the spiritual essence extraction system. In response to this challenge to their power, the guardian of the area, Lingji Bodhisattva, transformed the entire Kingdom of Flowing Sand into rat demons and framed Yellow Wind Sage for the calamity, thus reconstructing the legitimacy of the Western Paradise’s rule and ensuring the continuous supply of faith to maintain their power.

The player’s task as the “Destined One” upon reaching Yellow Wind Ridge is to defeat the Yellow Wind Sage and retrieve the Ear, one of the six sense faculties. The core conflict arises from this mission: defeating the Yellow Wind King effectively renders the player complicit in the violent oppression enacted by divine authority, while failing to do so prevents further progress in the game, creating an impasse. Caught in this double bind, the player becomes ensnared in the game’s disciplinary mechanisms, wherein progression necessitates both ideological submission (implicitly legitimizing the violence of divine authority) and mechanical endurance (repeated deaths in the boss fight). Here, the game’s mechanics and narrative text work in tandem to materialize oppression as a dual-layered traumatic experience that the player is compelled to internalize.

If the player simply follows the procedural logic of completing the main task nodes, they inevitably become trapped in a disciplinary loop. After collecting all five of Sun Wukong’s faculties, the Destined One is transformed into the vessel for Sun Wukong’s resurrection, completing the process of identity alienation into the home sacer through the violent imposition of the Golden Hoop. This ending fundamentally represents a key step in the reproduction of divine authority’s power: the player’s character is fully integrated into the divine order, losing any agency in their recognition of their own subjectivity.

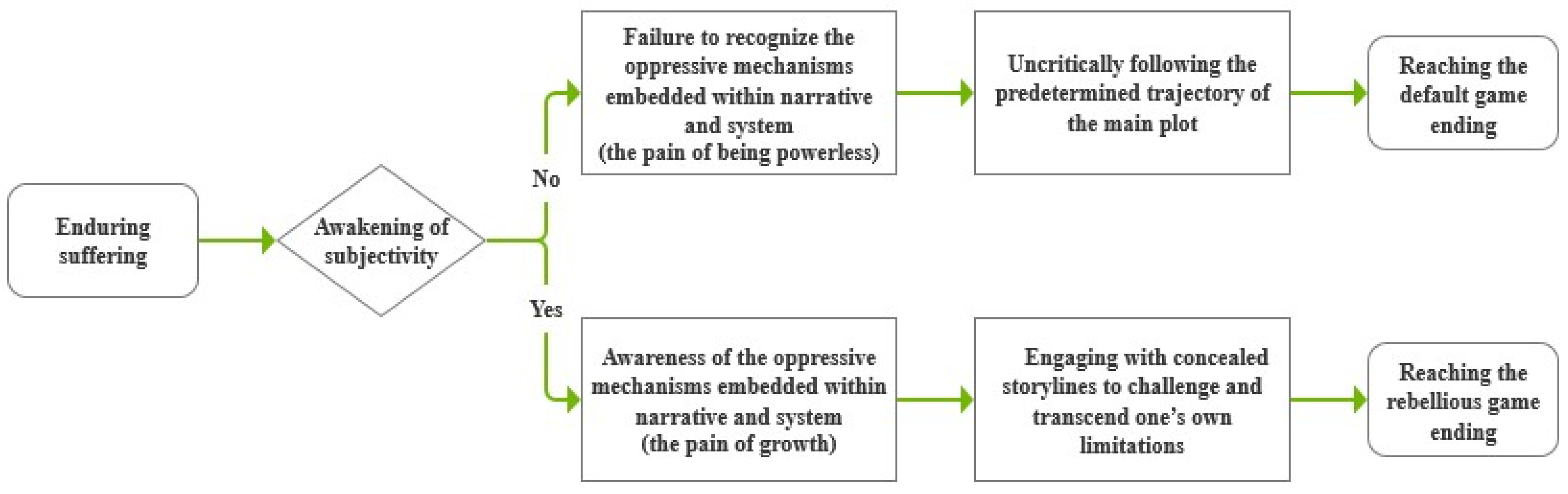

The possibility of breaking free from this ideological trap lies in the critical awareness that emerges through the player’s experience of suffering. As the player gradually deconstructs the narrative of “Destiny”, their subjectivity shifts from “immersion” to “distantiation”. This transformation is embodied in the player’s uncovering of hidden storylines—which expose the hypocrisy of the Heavenly Court—and the final confrontation with the hidden boss Erlang, the Sacred Divinity, at Mei Mountain, where they retrieve the sixth faculty, “Mind”. Notably, triggering these hidden quests requires players to break free from the game’s predefined cognitive framework, fostering a dual critical perspective within the virtual space: questioning the legitimacy of the Heavenly Court’s rule while simultaneously reflecting on the disciplinary nature of the game’s mechanics. This dual deconstruction is enabled by the reflective subjectivity the player develops through their experience of suffering (

Figure 3).

In the battle against the hidden boss Erlang, the identity of the “Destined One” is ultimately deconstructed. Erlang’s role extends beyond the conventional function of a boss fight; he serves as a reflective critic of the Heavenly Court’s governance. During the battle, Erlang (

Figure 4) asks the Destined One: “The world is cruel, and destiny unfair. Do you see it now?” This question is not merely directed at the avatar but also operates as a meta-game inquiry into the player’s subjectivity. Only when the player awakens to their own subjectivity can they begin to truly decode the biopolitical framework embedded within

Black Myth: Wukong.

Within the narrative framework of

Black Myth: Wukong, the Heavenly Court constructs a state of exception, excluding not only demons and humans, but also gods and buddhas who refuse to conform to its established order. This exclusion reduces them to bare life—beings stripped of legal and moral protections, rendering them entirely subject to manipulation. The Yellow Wind Sage serves as a prime example: deliberately framed and instrumentalized by the Heavenly Court, he is transformed into one of the calamities the Destined One must overcome. Simultaneously, human beings, perpetually afflicted by man-made disasters, plead for the protection of the gods and buddhas, unaware that the Heavenly Court secretly cultivates human embryos to produce immortality fruits and extract spiritual essence. These bare lives, deprived of agency and identity, are not only fully integrated into the mechanisms that sustain the Heavenly Court’s rule but also serve as the material foundation of its sovereignty and legitimacy [

12]. However, through their experiences of suffering, players may awaken to the deception of the gods and buddhas, leading them toward an entirely different ending. In the hidden ending, the old monkey places the Golden Hoop before the Destined One, who finally opens his tightly shut eyes—an unmistakable act of resistance. The completion of the hidden ending signifies that through their experience of suffering, the players have seamlessly merged their spirit with the Destined One’s actions. By reclaiming the six sense faculties, the Destined One—now seeing through the player’s eyes—recognizes the hidden machinations shaping his fate. It is in this moment of despair that the possibility of a new subjectivity and new desires emerges [

25].

Refusing to wear the Golden Hoop signifies the Destined One’s rejection of the Heavenly Court’s authority, aligning with Agamben’s analysis of humans as “pure potentiality” [

26]. Agamben [

12] emphasizes that humans must retain the power to say “no” to reality: “If potentiality is to have its own consistency and not always disappear immediately into actuality, it is necessary that potentiality be able not to pass over into actuality, that potentiality constitutively be the potentiality not to (do or be), or, as Aristotle says, that potentiality be also im-potentiality (adynamia)”. This ability to say “no” to actuality aligns with Agamben’s concept of the form-of-life, which resists the biopolitical capture of bare life. The form-of-life refuses the separation of zoē and bios, merging them into a unified existence that defies biopolitical control. It is a possibility of life, existing as life’s “potentiality” [

27].

In Black Myth: Wukong, the game does not provide a clear, overt pathway for the player to actively resist the Heavenly Court. The narrative concludes with the player reclaiming the six sense faculties and rejecting the imposition of the Golden Hoop. However, resistance does not end at this point; rather, it persists as a latent force within the infinite cycles of suffering experienced by countless players, continuously existing as a potentiality to resist biopolitics.