A New Paradigm of Metaverse Philosophy: From Anthropocentrism to Metasubjectivity

Abstract

1. Introduction and Related Works

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Co-Evolution and Socio-Technological Foundations

- Technological development and influence of immersive technologies Artificial Intelligence (AI) [22], Machine Learning (ML) [23], Natural Language Processing (NLP) [24], Linguometry, Stylemetry and Glottochronology (LLM) [25], Computer Vision [26], Deep Learning [27], Reinforcement Learning [28], Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [29], Recommendation Systems [30], Autonomous Agents [31], Predictive Analytics [32], Robotics [33], Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) [34], Edge Artificial Intelligence (Edge AI) [35], Large Language Models (LLM) [36], Internet of Things (IoT) [37], and Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) [38] on the possibilities of interaction and creation in the Metaverse;

- Social adaptation of users to life and interaction in virtual worlds, formation of new forms of social behavior in digital ecosystems;

- Legal challenges and the response and adaptation of existing and new legal boundaries to regulate relations in virtual spaces, as well as to ensure the protection of the rights and freedoms of subjects and objects in the Metaverse;

- Cultural changes, transformation, and evolution of established traditions, cultural and moral norms, social and human values in response to the opportunities and challenges offered by the Metaverse.

2.2. Proto-Metaverse: Philosophy Before the Emergence of Digital Worlds

2.3. From Anthropocentrism to Postanthropocentrism

- The equality of subjects implies that the human being is not the sole or superior subject of reality, but that all subjects, regardless of the nature of their consciousness (biological or digital), have an equal right to exist and participate in the creation and transformation of reality [79];

- The dynamism of identity transformation, which is characterized by the fact that identity is no longer limited to human corporeality or consciousness, but, on the contrary, it can be dynamic, transforming through interactions with different digital avatars or electronic personalities, which changes traditional notions of individuality and uniqueness [80,81];

- Recognition of artificial intelligence (AI) as a subject, since in the near future, modern AI, in particular neural networks, are capable of learning, decision-making, and even the creation of new algorithms, which effectively makes them equal participants in human interactions in the Metaverse [84], i.e., possible practical recognition that such subjects may have their own consciousness and intellectual capabilities that exceed the limits of humanoids’ capabilities;

3. Results

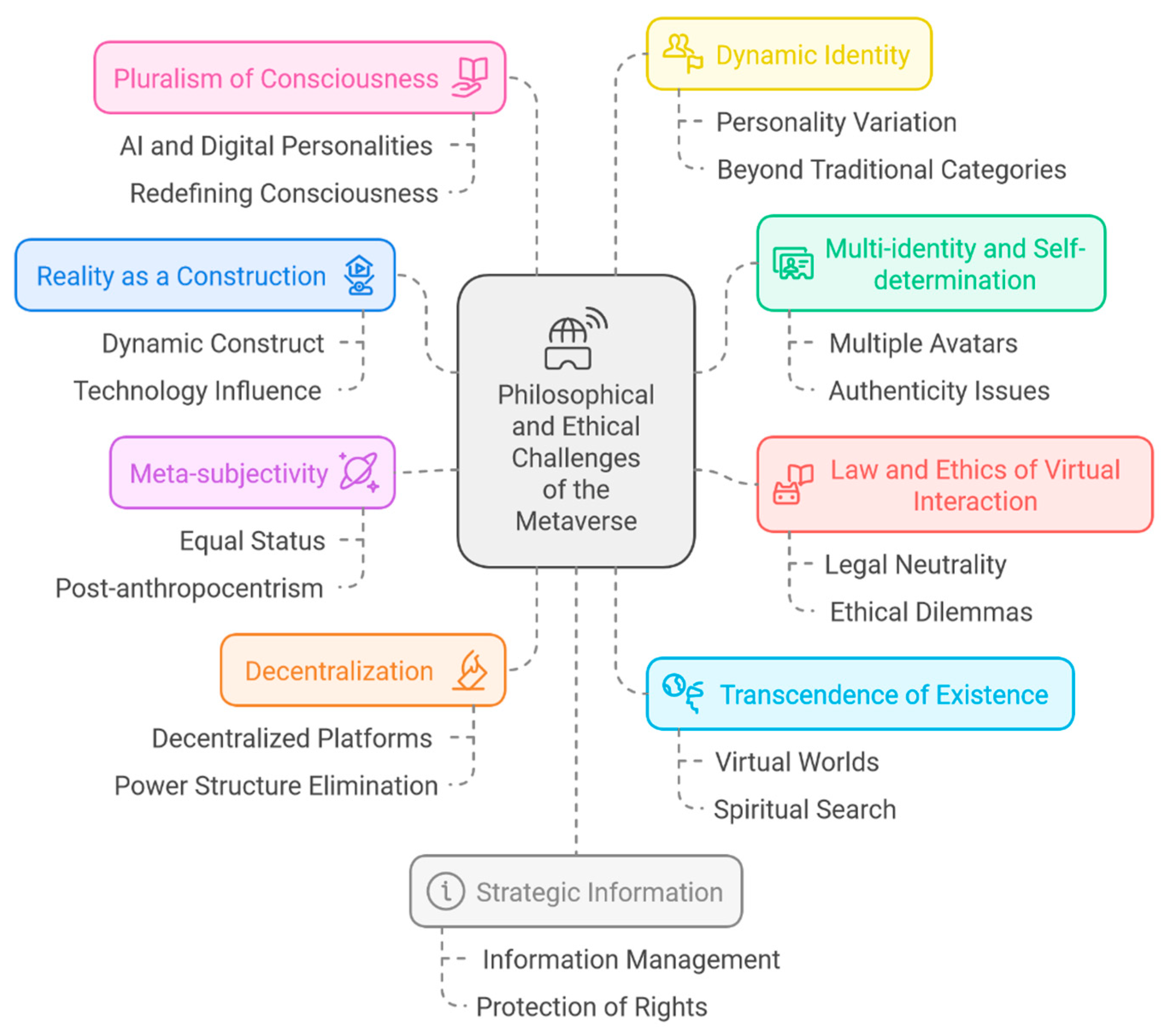

3.1. Metaverse Philosophy: Basic Postulates Synthesis

- Reality is a multidimensional structure. The Metaverse is a dynamic construct that is constantly evolving and can be modified and expanded with technology, which in turn embraces the rethinking of traditional ideas about objective reality, which ceases to be only physical or virtual, but becomes multidimensional;

- Multi-identity and self-determination. In the Metaverse, the subject acquires many variations in their own identity using infinite digital constructions of avatars, digital personalities, and electronic humanoids, which makes the problem of the essence of the “I” and the authenticity of virtual self-expressions relevant;

- Law and ethics of virtual interaction. The absence of physical boundaries in the Metaverse creates new ethical dilemmas, such as the problem of legal and moral neutrality of virtual actions and misdemeanors, their consequences, and raises the issue of the need to consider the interests of all Metaverse entities and the application of the principles of mutual respect, is each subject recognizes the other’s right to exist and self-expression;

- Metasubjectivity or ontological equality of Metaverse subjects. Metasubjectivity is based on the postulate of the equality of being of all digital subjects regardless of their origin or nature, i.e., the equality of participants in virtual reality with unique consciousness and value (it is a normative concept for the governance mechanisms’ design (including algorithmic fairness and rights in e-jurisdiction), not an empirical claim about the existence of consciousness);

- Power Transformation and Decentralization of the Metaverse. Virtual ecosystems are essentially decentralized cross-border digital platforms that may not use traditional forms and attributes of the state, structures, and authorities;

- Transcendence of existence and consciousness. The creation of personal virtual worlds and ecosystems for the development of new horizons of spiritual search and self-realization gives a positive impetus to the combination of different forms of existence and consciousness through the integration and interaction of various subjects of virtual ecosystems;

- Pluralism of consciousness. The postulate predicts the multiformation of consciousness, since it may not be limited to biological life forms but can be implemented in the form of AI and digital personalities other than human, which are no less authentic, followed by a rethinking of traditional ideas about consciousness and self-awareness;

- Dynamic identity. The ability of analog and digital subjects, through variability and combination of characteristics and attributes of their personality, to go beyond traditional physical identities;

- Strategic information through the awareness of the fact that information and data become not only new resources, but also habitats that require responsible management, which implies the crucial control of the use of these information resources and the protection of the equality of all subjects in such an environment.

- Fundamental fairness and equality in the Metaverse through ensuring equal opportunities for all actors, regardless of their nature.

3.2. Destruction of Virtual Environments

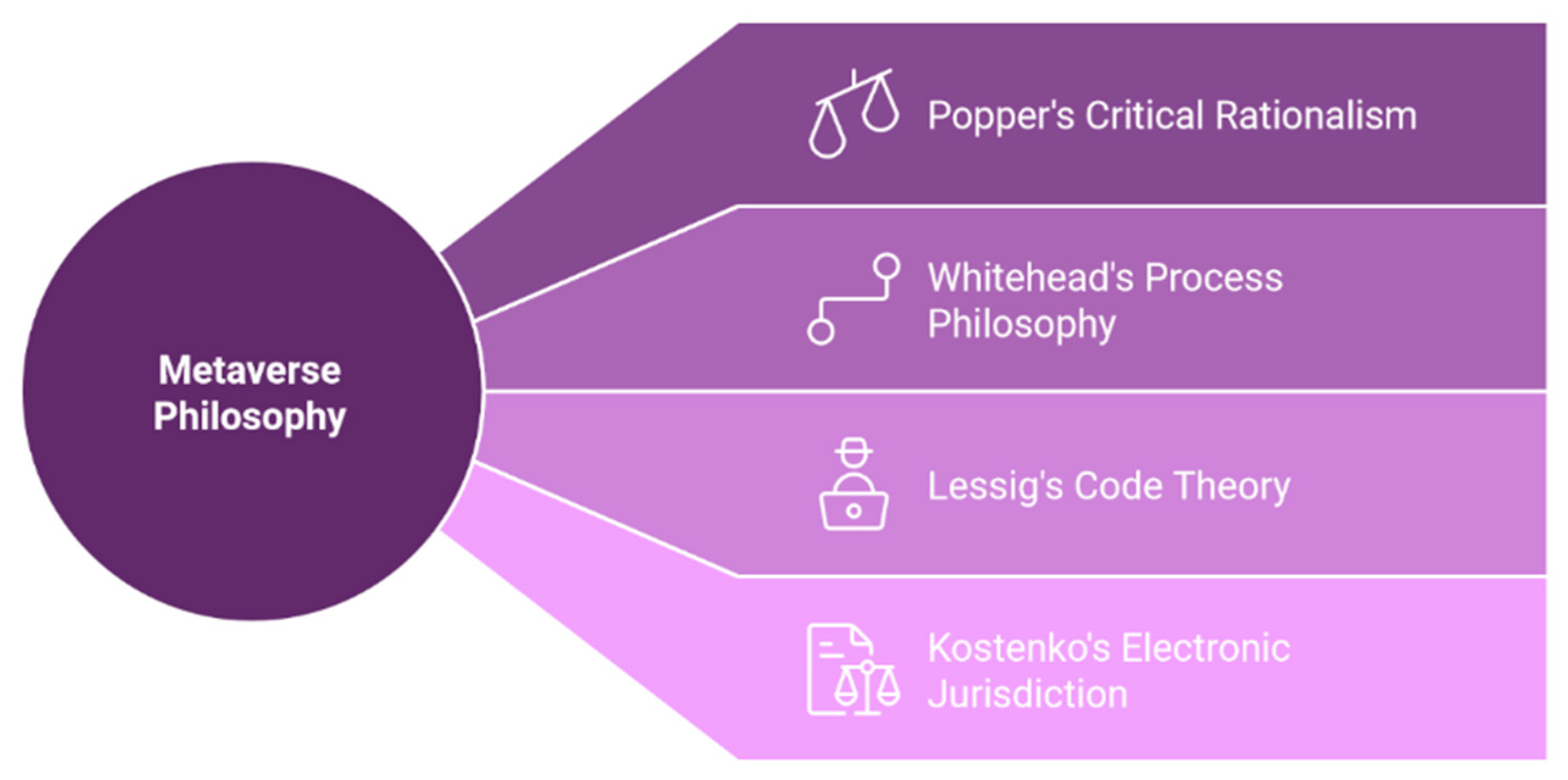

3.3. Metareality Model: Synthesis of Philosophies

- Karl Popper—critical rationalism and the concept of three worlds. Karl Popper believed that scientific knowledge develops through critical realism, the process of hypothesis formation and testing, where erroneous theories are rejected, and better ones replace them as a means of achieving truth [88]. K. Popper’s concept of the three worlds describes the structure of reality, dividing it into the physical world, the world of consciousness, and the world of objective knowledge [89,90]. It is a key part of his philosophical system, proposing to unite the material, psychological, and intellectual into a single coordinate system of reality of the three worlds [91,92]. According to K. Popper, the physical world is a physical reality and, at the same time, is the foundation for the worlds of consciousness and objective knowledge, providing them with a material basis for existence. The world of consciousness is responsible for the personal perception of physical reality and the interpretation of objective knowledge. In turn, the World of Objective Knowledge contains the products of human intelligence and culture: scientific theories, mathematical theorems, philosophical doctrines, literary works, art, technological inventions, etc. [93]. K. Popper emphasizes the interdependence and interaction between these three worlds, which indicates a deep understanding of the structure of reality, a complex interaction between the material world, subjective experience, and objective knowledge [94].

- The Philosophy of Processes by Alfred North Whitehead. Alfred North Whitehead considers reality as a process made up of ever-changing events. In his works, he positions his metaphysical system, explores the development of ideas in human culture, as well as the interaction of science and philosophy. Alfred North Whitehead argued that the fundamental unit of reality is not objects, but processes or events, which he called “actual events” or “actual occasions”. This concept is the basis of his metaphysical system, known as procedural philosophy or philosophy of processes [95]. Actual occasions are the smallest units of reality, which are not static objects, but dynamic processes. Each current event is an instantaneous and unique integration of numerous influences from previous events. Each relevant event has its own internal experience or subjective aspect, which Alfred North Whitehead calls the “subjective form”. Once its subjective process is complete, the event becomes part of objective reality, accessible to other events as “objective immediacy”. That is, a current event is formed from a multitude of opportunities and influences or a “transition” from potential to actual, where each event chooses a certain path among many possible options. Alfred North Whitehead assumes the existence of an eternal nature that contains all possible forms and ideas and their influence on future events. Thus, each relevant event becomes part of the consequential nature and affects the further development of reality. Alfred North Whitehead emphasizes that reality is not static but is constantly in the process of change and development. Each current event contributes to this constant evolution, introducing new elements and influencing future events. This is a fundamental property of reality, which provides the possibility of the emergence of new forms and structures.

- The Theory of “Code” by Lawrence Lessig. Lawrence Lessig argues that on the Internet, “code is the law”, that is, technological protocols and software determine how information is distributed and controlled. L. Lessig considers its architecture, technical components, or capabilities, or “code” to be the key regulator of cyberspace. It is the code that determines the order of use of cyberspace, just as social relations in real space are subject to public administration. L. Lessig argues that in a fundamental sense, the code of cyberspace is its Constitution. The code defines the conditions under which people access cyberspace and establishes rules that control their behavior. L. Lessig was the first to draw attention to the need for laws that would simultaneously ensure regulation in cyberspace and minimize restrictions on human rights and freedoms. This highlights the role of technology in shaping social and legal norms [96,97].

- Metaverse e-jurisdictions paradigm and globalization of law. In today’s world, when the Metaverse is becoming an integral part of the digital landscape, the issue of its legal regulation becomes important. The cross-border nature of virtual ecosystems creates gaps in international law and national jurisdictions, which makes it impossible to ensure the territorialization of the Metaverse. That is, there is the fact of the impossibility of applying territorial concepts of international law to subjects and their activities and objects that exist or operate in or through the Metaverse, as well as the inability of states to ensure their sovereignty in the Metaverse, even by creating national Metaverses [98].

- Critical rationalism of Karl Popper as a methodological basis for the development and development of law in the Metaverse, where each norm is considered as a hypothesis that can be rejected or transformed and quickly improved;

- The theory of “Code” by L. Lessig, which is the foundation of technological processes of law formation in the Metaverse, according to the principle “code is law”, which technologically provides freedoms or restrictions on the formation of legal and social norms;

- The process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead to understand the Metaverse as a dynamic system in which legal, technical, and social elements are in constant interaction and interchange, reality as a set of processes and events, emphasizing the coherence and interdependence of all elements of reality;

- E-jurisdictions of Oleksii Kostenko, as a practical implementation of the creation of the right of the Metaverse virtual environment.

3.4. Individual Rights, Mechanisms for the Power Transfer, and Their Implementation in E-Jurisdiction

- A unified system of identification and attribution of legal capacity (minimum KYC and ABI standards taking into account privacy);

- Formalization of the will expression, within which framework the “transfer act” is signed by the user (or agent) with a machine-readable protocol;

- Notarial-analogous services in the cryptographic notarial services and blockchain registries form with immutability and audit traceability;

- Built-in mechanisms for revocation and revocation of powers (time-lock, escape-hatch, emergency stop) and algorithmic ability to reverse the revocation in case of proven abuse;

- Clear rules of representation and fiduciary duties for autonomous agents.

- The principle of transparency, within the framework of which all delegation rules must be formalized and available for audit;

- The principle of reversibility, within the framework of which the existence of technical and legal mechanisms for the abolition of abuses is determined;

- The principle of proportionality, within which the level of formality and evidence is determined depending on the power’s nature being transferred;

- The principle of interoperability, which states that transmission standards must be comparable across borders;

- The principle of meta-responsibility, which holds protocol designers responsible for the predictability of the side effects of the transmission mechanics.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gregor, A.J. Classical Marxism and Maoism: A Comparative Study. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 2019, 52, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Dal Monte, O.; Chang, S.W.C. Levels of Naturalism in Social Neuroscience Research. iScience 2021, 24, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todres, L.; Wheeler, S. The Complementarity of Phenomenology, Hermeneutics and Existentialism as a Philosophical Perspective for Nursing Research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2001, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffro, L. Contempt and Invisibilization. Philosophies 2024, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennekes, B. From the Philosopher’s Stone to AI: Epistemologies of the Renaissance and the Digital Age. Philosophies 2025, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivinen, O.; Piiroinen, T. Evolutionary Understanding of the Human Mind and Learning–in Accordance with Transactional Naturalism and Methodological Relationalism. Phys. Life Rev. 2019, 31, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, G.S. The Evolution of Western Philosophical Concepts on Social Determinants of Mental and Medical Health. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Jamshidi, M.; Manh, B.D.; Chu, N.H.; Nguyen, C.-H.; Hieu, N.Q.; Nguyen, C.T.; Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, D.N.; Van Huynh, N.; et al. Enabling Technologies for Web 3.0: A Comprehensive Survey. Comput. Netw. 2025, 264, 111242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbunge, E.; Jiyane, S.; Muchemwa, B. Towards Emotive Sensory Web in Virtual Health Care: Trends, Technologies, Challenges and Ethical Issues. Sens. Int. 2022, 3, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chickerur, S.; Balannavar, S.; Hongekar, P.; Prerna, A.; Jituri, S. WebGL vs. WebGPU: A Performance Analysis for Web 3.0. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 233, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, M.; Zhan, M.; Guan, D. The Effect of the Realism Degree of Avatars in Social Virtual Worlds: The perspective of self-presentation. Inf. Manag. 2025, 62, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Hui, P. Framing Metaverse Identity: A Multidimensional Framework for Governing Digital Selves. Telecommun. Policy 2025, 49, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hong, J.; Zhu, J.; Duan, S.; Xia, M.; Chen, J.; Sun, B.; Xi, M.; Gao, F.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Humanoid Electronic-Skin Technology for the Era of Artificial Intelligence of Things. Matter 2025, 8, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougen, P.D.; Young, J.J. Fair Value Accounting: Simulacra and Simulation. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2012, 23, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladov, S.; Vysotska, V.; Sokurenko, V.; Muzychuk, O.; Nazarkevych, M.; Lytvyn, V. Neural Network System for Predicting Anomalous Data in Applied Sensor Systems. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liang, C. Analyzing Wealth Distribution Effects of Artificial Intelligence: A Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium Approach. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Research on the Optimization of Digital Object System by Integrating Metadata Standard and Machine Learning Algorithm. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 262, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, I.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Panniello, U. Digital Business Model Innovation in Metaverse: How to Approach Virtual Economy Opportunities. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Complex Social Networks in Online Sharing of Experiences: Self- and Other-Positioning. Discourse Context Media 2025, 66, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhurst, M.A.; Koskella, B. Experimental Coevolution of Species Interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, N.; Weijers, D. The Real Ethical Problem with Metaverses. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2023, 5, 1226848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladov, S.; Sachenko, A.; Sokurenko, V.; Muzychuk, O.; Vysotska, V. Helicopters Turboshaft Engines Neural Network Modeling under Sensor Failure. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2024, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vysotska, V.; Nazarkevych, M.; Vladov, S.; Lozynska, O.; Markiv, O.; Romanchuk, R.; Danylyk, V. Devising a Method for Detecting Information Threats in the Ukrainian Cyber Space Based on Machine Learning. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2024, 6, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytvyn, V.; Vysotska, V.; Pukach, P.; Nytrebych, Z.; Demkiv, I.; Kovalchuk, R.; Huzyk, N. Development of the Linguometric Method for Automatic Identification of the Author of Text Content Based on Statistical Analysis of Language Diversity Coefficients. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2018, 5, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytvyn, V.; Vysotska, V.; Pukach, P.; Bobyk, I.; Uhryn, D. Development of a Method for the Recognition of Author’s Style in the Ukrainian Language Texts Based on Linguometry, Stylemetry and Glottochronology. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2017, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niiranen, J. Integrating Computer Vision Techniques with Finite Element Phase Field Damage Analysis. Comput. Struct. 2025, 315, 107793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekundayo, O.S.; Ezugwu, A.E. Deep Learning: Historical Overview from Inception to Actualization, Models, Applications and Future Trends. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 181, 113378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, N.M. Comparison of Distance and Reinforcement-Learning Rules in Social-Influence Models. Neurocomputing 2025, 649, 130870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Xiang, X.; Kong, W.; Zhang, J.; Yao, J. SF-GAN: Semantic Fusion Generative Adversarial Networks for Text-to-Image Synthesis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 262, 125583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Jang, Y.-J.; Sung, T.-E. Graph-Based Technology Recommendation System Using GAT-NGCF. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 288, 128240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccialli, F.; Chiaro, D.; Sarwar, S.; Cerciello, D.; Qi, P.; Mele, V. AgentAI: A Comprehensive Survey on Autonomous Agents in Distributed AI for Industry 4.0. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaketheep, K.; Al-Ahmed, H.; Mansour, A. Beyond Purchase Patterns: Harnessing Predictive Analytics to Anticipate Unarticulated Consumer Needs. Acta Psychol. 2025, 257, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, B.; Frennert, S. Towards an Experiential Ethics of AI and Robots: A Review of Empirical Research on Human Encounters. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 219, 124264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speich, J.E.; Klausner, A.P. Artificial Intelligence in Urodynamics (AI-UDS): The Next “Big Thing.”. Continence 2025, 13, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; Qi, C. SecureEI: Proactive Intellectual Property Protection of AI Models for Edge Intelligence. Comput. Netw. 2024, 255, 110825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytvyn, V.; Kuchkovskiy, V.; Vysotska, V.; Markiv, O.; Pabyrivskyy, V. Architecture of System for Content Integration and Formation Based on Cryptographic Consumer Needs. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 13th International Scientific and Technical Conference on Computer Sciences and Information Technologies (CSIT), Lviv, Ukraine, 11–14 September 2018; pp. 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Yadav, M.; Singh, Y.; Moreira, F. Techniques in Reliability of Internet of Things (IoT). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 256, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Crespi, N.; Minerva, R.; Liang, W.; Li, K.-C.; Kołodziej, J. DPS-IIoT: Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge Proof-Inspired Access Control towards Information-Centric Industrial Internet of Things. Comput. Commun. 2025, 233, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muravskyi, V.; Pytel, S.; Bashutskyy, R. Technological Anthropocentrism in Accounting for Industry 5.0. Visnyk Ekon.—Her. Econ. 2025, 4, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohayati, Y.; Abdillah, A. Digital Transformation for Era Society 5.0 and Resilience: Urgent Issues from Indonesia. Societies 2024, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovianko, M.; Terziyan, V.; Branytskyi, V.; Malyk, D. Industry 4.0 vs. Industry 5.0: Co-Existence, Transition, or a Hybrid. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czvetkó, T.; Sebestyén, V.; Abonyi, J. Key Factors of Industry 5.0-Based Organizational Sustainability. Technol. Soc. 2025, 83, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, Z.; Leng, J.; Zhao, J.L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, D.; Tao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C.; et al. Human-Centric Artificial Intelligence towards Industry 5.0: Retrospect and Prospect. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 47, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.K.M.A.; Hasan, M.K.; Hassan, R.; Islam, S.; Abbas, H.S. False Data Injection Attack Dataset for Classification, Identification, and Detection for IIoT in Industry 5.0. Data Brief 2025, 61, 111692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eve, S. Augmented Reality. In The Encyclopedia of Archaeological Sciences; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, T. Mastering the Art of VR: On Becoming the HIT Lab Cybrarian. Electron. Libr. 1993, 11, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinghurst, M. Grand Challenges for Augmented Reality. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 2, 578080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garassini, S.; Mattei, M.G. Evening Presentation the State of the Art in Virtual Reality. In Human and Machine Vision; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sra, M. Enhancing the Sense of Presence in Virtual Reality. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2023, 43, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, L. Virtual and Augmented Reality 2020. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2000, 20, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B.; Soares, M.; Neves, A.; Soares, G.; Lins, A. The State of the Art in Virtual Reality Applied to Digital Games: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the AHFE International, New York, NY, USA, 24–28 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, H. The Unexamined Second Life Isn’t Worth Living: Virtual Worlds and Interactive Art. Comp. Technol. Transf. Soc. 2007, 35, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, H. The Role of Reflection in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Pac. Philos. Q. 1999, 80, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenczewska, O. Expansion of Self-Consciousness in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Kant-Studien 2019, 110, 554–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittgenstein, L. Tractatus Logico-Filosoficus; Philosophical Research; The Basics: Kyiv, Ukraine, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D. The “Middle Wittgenstein”: From Logical Atomism to Practical Holism. Synthese 1991, 87, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopek, O. Transformation of understanding of social reality in according to works of P. Berher, T. Lukman and N. Luman. Multiversum 2019, 1–2, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. On the Possibility of Social Scientific Knowledge and the Limits of Naturalism. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1978, 8, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, B. Naturalism as a Philosophy of Social Science. Philos. Soc. Sci. 1984, 14, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, F.J. Phenomenological Research Methods for Counseling Psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, D. Husserl’s Phenomenology. Choice Rev. Online 2003, 41, 41-0238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husserl. Sartre and His Predecessors. Available online: https://referenceworks.brill.com/display/entries/RGG4/SIM-10182.xml (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Warren, N. Edmund Husserl and Eugen Fink: Beginnings and Ends in Phenomenology, 1928–1938 (review). J. Hist. Philos. 2005, 43, 496–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prole, D. The Beginnings of Phenomenology in Yugoslavia: Zagorka Mićić on Husserl’s Method. Early Phenomenol. Cent. East. Eur. 2020, 113, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Erving Hoffman; Routledge: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.; Murphy, J.; Owens, D.; Khazanchi, D.; Zigurs, I. Avatars, People, and Virtual Worlds: Foundations for Research in Metaverses. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslund, S.P. Postcolonialism, the Anthropocene, and New Nonhuman Theory: A Postanthropocentric Reading of Robinson Crusoe. Ariel 2021, 52, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdy, W. Anthropocentrism: A Modern Version: Belief in the value and creative potential of the human phenomenon is requisite to our survival. Science 1975, 187, 1168–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, L. The Anthropocentric Illusion. In Capitalism and Environmental Collapse; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 391–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribben, J.; Fagan, J.M. Anthropocentric Attitudes in Modern Society; Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.I.; Lombard, M.; Henriksen, L.; Steuer, J. Anthropocentrism and Computers. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1995, 14, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, R. Critical Posthuman Knowledges. South Atl. Q. 2017, 116, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, I.; Wang, Z.; O’Leary, T.; Corballis, P. Forgetting the Bicentennial Man: Discussing Why Anthropocentric Frameworks of Consciousness Should Be Avoided for Artificial Entities. J. Artif. Intell. Conscious. 2022, 09, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idhe, D. Postphenomenology—Again? The Centre for STS Studies: Aarhus, Denmark, 2003; 30p, Available online: https://sts.au.dk/fileadmin/sts/publications/working_papers/Ihde_-_Postphenomenology_Again.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Verbeek, P.-P. Politicizing Postphenomenology. Philos. Eng. Technol. 2020, 33, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgmann, A. Technology. In A Companion to Heidegger; Hubert, L., Dreyfus, H.L., Wrathall, M.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. The Philosophy of the Metaverse. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2023, 25, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W. The Dissemination of Metaverse from an Embodied Perspective and Its Shift Towards Human Physicality. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 2, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-I.; Dennis, A.R.; Dennis, A.S. Avatar-Mediated Communication and Social Identification. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2023, 40, 1171–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looy, J.V. Online Games Characters, Avatars, and Identity. In The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, T.; Janeš, L.; Novaković, V. Aesthetics, Psyche and Media: A Manifold of Mimesis in the Age of Simulation. Conatus–J. Philos. 2022, 7, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triberti, S.; Durosini, I.; Aschieri, F.; Villani, D.; Riva, G. Changing Avatars, Changing Selves? The Influence of Social and Contextual Expectations on Digital Rendition of Identity. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccennini, F. Digital Avatars. Philos. Today 2021, 65, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-The, T.; Pham, Q.-V.; Pham, X.-Q.; Nguyen, T.T.; Han, Z.; Kim, D.-S. Artificial Intelligence for the Metaverse: A Survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 117, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczyński, B. Personal Identity in the Era of Remote Living. Avatars in the Theatre of Cyberreal Life. Kult. Wartości 2023, 35, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailenson, J.N.; Beall, A.C. Transformed Social Interaction: Exploring the Digital Plasticity of Avatars. In Proceedings of the Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Banff, AB, Canada, 4–8 November 2006; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, O.V.; Zhuravlov, D.V.; Nikitin, V.V.; Manhora, V.V.; Manhora, T.V. A Typical Cross-Border Metaverse Model as a Counteraction to Its Fragmentation. Bratisl. Law Rev. 2024, 8, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, P.; Odağ, Ö. Popper Was Not a Positivist: Why Critical Rationalism Could Be an Epistemology for Qualitative as Well as Quantitative Social Scientific Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2018, 17, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olifer, O. Karl Popper. The logic of Scientific Discovery. A Survey of Some Fundamental Problems. Actual Probl. Mind Philos. J. 2021, 22, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. Knowledge and the Body-Mind Problem. In Defence of Interaction; Notturno, M.A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod, R.J. The History and Ideas of Critical Rationalism: The Philosophy of Karl Popper and Its Implications for OR. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2009, 60, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawwad, M. Karl Popper’s concept of ‘world 3’. Pak. J. Soc. Res. 2023, 5, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krige, J. Popper’s Epistemology and the Autonomy of Science. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1978, 8, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topitsch, E. On Early Forms of Critical Rationalism. Boston Stud. Philos. Sci. 1984, 79, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.N. Science and the Modern World; Open Road Media: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lessig, L. Code Version 2.0; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006; 409p, Available online: https://archive.org/download/Code2.0/Code_text.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Lessig, L. The Laws of Cyberspace. In Proceedings of the Taiwan Net’98 Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 3 March 1998; Available online: https://cyber.harvard.edu/works/lessig/laws_cyberspace.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Tsagourias, N. Law, Borders and the Territorialisation of Cyberspace. Indones. J. Int. Law 2017, 15, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, O.; Golovko, O. Metaverse electronic jurisdiction: Challenges and risks legal regulation of virtual reality. Inf. Law 2023, 1, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kostenko, O.; Zhuravlov, D.; Dniprov, O.; Korotiuk. Metaverse: Model Criminal Code. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 2023, 9, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, O.; Furashev, V.; Zhuravlov, D.; Dniprov, O. Genesis of Legal Regulation Web and the Model of the Electronic Jurisdiction of the Metaverse. Bratisl. Law Rev. 2022, 6, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, O.; Jaynes, T.; Zhuravlov, D.; Dniprov, O.; Usenko, Y. Problems of using autonomous military AI against the background of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine. Balt. J. Leg. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wang, Y.; Hui, P. Identity, Crimes, and Law Enforcement in the Metaverse. Comput. Soc. 2022, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlLouzi, A.S.; Alomari, K.M. Adequate Legal Rules in Settling Metaverse Disputes: Hybrid Legal Framework for Metaverse Dispute Resolution (HLFMDR). Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2023, 7, 1627–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, M. Is a ‘smart contract’ really a smart idea? Insights from a legal perspective. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2017, 33, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. A Legal Brief Study of Metaverse. Lib. Arts Innov. Cent. 2022, 9, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, O.V.; Manhora, V.V. Metaverse: Legal Prospects for Regulating the Use of Avatars and Artificial Intelligence. Leg. Sci. Electron. J. 2022, 2, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostenko, O.; Dniprov, O.; Zhuravlov, D.; Tykhomyrov, O.; Vladov, S. A New Paradigm of Metaverse Philosophy: From Anthropocentrism to Metasubjectivity. Philosophies 2025, 10, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060117

Kostenko O, Dniprov O, Zhuravlov D, Tykhomyrov O, Vladov S. A New Paradigm of Metaverse Philosophy: From Anthropocentrism to Metasubjectivity. Philosophies. 2025; 10(6):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060117

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostenko, Oleksii, Oleksii Dniprov, Dmytro Zhuravlov, Oleksandr Tykhomyrov, and Serhii Vladov. 2025. "A New Paradigm of Metaverse Philosophy: From Anthropocentrism to Metasubjectivity" Philosophies 10, no. 6: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060117

APA StyleKostenko, O., Dniprov, O., Zhuravlov, D., Tykhomyrov, O., & Vladov, S. (2025). A New Paradigm of Metaverse Philosophy: From Anthropocentrism to Metasubjectivity. Philosophies, 10(6), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060117