An Optimized Protocol for Enzymatic Hypothiocyanous Acid Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Materials

- Unpasteurized bovine milk collected and stored at +4–8 °C for no more than one day before freezing at −18 °C (stable at −18 °C for at least 6 months).

- Ammonium Sulfate ((NH4)2SO4) (Sigma-Aldrich, 7783-20-2, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Bovine Liver Catalase (Sigma-Aldrich, 9001-05-2, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Capsule membrane filter, pore size of 0.45 µm, polyether sulphone (Sterlitech, 1470233, Auburn, WA, USA).

- Citric Acid Monohydrate (C6H8O7·H2O) (Sigma-Aldrich, 5949-29-1, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Clear, uncoated, flat-bottom 96-well plates, preferably divided into 8-well strips (Corning, 96-well Clear Polystyrene Not Treated Stripwell™ Microplate, 2593, Corning, NY, USA).

- Guaiacol ((CH3O)C6H4OH) (Sigma-Aldrich, 90-05-1, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Hydrogen Peroxide, 8.5 M (H2O2) (Sigma-Aldrich, 7722-84-1, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Hydrophobic resin for protein separation packed in a chromatography column (Cytiva, Butyl-Sepharose Fast Flow, 17098001, Marlborough, MA, USA).

- Size-exclusion resin suitable for 78 kDa-protein separation packed in chromatographic column (Cytiva, Superdex 200, 17104301, Marlborough, MA, USA).

- Sodium Chloride (NaCl) (Sigma-Aldrich, 7647-14-5, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) (Sigma-Aldrich, 1310-73-2, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Sodium Phosphate Dibasic Heptahydrate (Na2HPO4·7H2O) (Sigma-Aldrich, 7782-85-6, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Sodium Phosphate Monobasic Monohydrate (NaH2PO4·H2O) (Sigma-Aldrich, 10049-21-5, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Sodium Thiocyanate (NaSCN) (Sigma-Aldrich, 540-72-7, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Strong cation exchanger resin for protein separation packed in a chromatography column (Bio-Rad, UNOSphere S, 156-0113, Hercules, CA, USA).

- Ultrafiltration units, MWCO 10 kDa (Sartorius, Vivaspin 500 columns, VS0101, Göttingen, Germany).

- Ultrafiltration units, MWCO 30 kDa (Sartorius, Vivaspin 20 columns, VS2022, Göttingen, Germany).

- UV transparent cuvettes (Sarsted, 67.759, Nümbrecht, Germany).

- 2,2′-Azinobis-(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulphonic) Diammonium Salt (ABTS) (Sidma-Aldrich, 30931-67-0, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- 15 mL conical tubes (SPL Life Sciences, 50115, Pocheon-si, Republic of Korea).

- 50 mL conical tubes (SPL Life Sciences, 50150, Pocheon-si, Republic of Korea).

- 0.5–10 μL disposable tips (ULPlast, OM-10-RF-C, Warszawa, Poland).

- 1–200 μL disposable tips (ULPlast, OM-200-RF-Y, Warszawa, Poland).

- 100–1000 μL disposable tips (ULPlast, OM-1000-RF-B, Warszawa, Poland).

- 5,5-Dithio-bis-(2-Nitrobenzoic Acid) (DTNB) (Sigma-Aldrich, 69-78-3, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- 0.5 mL Eppendorf-type tubes (SSIbio, 1310-00, Lodi, CA, USA).

- 2 mL Eppendorf-type tubes (SSIbio, 1110-00, Lodi, CA, USA).

- 2-Morpholinoethanesulfonic Acid Monohydrate (MES·H2O) (Sigma-Aldrich, 145224-94-8, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Equipment

- Automatic pipette, 0.5–10 μL (Eppendorf, 3123000020, Hamburg, Germany).

- Automatic pipette, 10–100 μL (Eppendorf, 3123000047, Hamburg, Germany).

- Automatic pipette, 100–1000 μL (Eppendorf, 3123000063, Hamburg, Germany).

- Centrifuge capable of generating 2500× g acceleration and cooling samples (Eppendorf, 5810R, Hamburg, Germany).

- Centrifuge capable of generating 12,000× g acceleration and cooling samples (Eppendorf, 5424R, Hamburg, Germany).

- Communicating vessels for linear gradient preparation (Bio-Rad, Model 495 Gradient Former, 1654121, Hercules, CA, USA).

- Cuvette spectrophotometer capable of measuring absorbance at 240, 280, and 412 nm (Agilent, Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

- 100 mL glass beakers, ×5 (BRAND, BR90624, Wertheim, Germany).

- 250 mL glass beaker (BRAND, BR91236, Wertheim, Germany).

- 500 mL glass beaker (BRAND, BR91217, Wertheim, Germany).

- 2 L glass beakers, ×2 (BRAND, BR91263, Wertheim, Germany).

- Laboratory balance (Accuris, Precision Balance, Denver, CO, USA).

- Laboratory ice generator (Fisher Scientific, CurranTaylor™ Scotsman Brand Flake Ice Maker Floor Model, Waltham, MA, USA).

- Laboratory spatula (Aldrich, Z283274; Scienceware, Z177962, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Magnetic stirrer (Fisher Scientific, Thermo Scientific™ Cimarec+™ Stirrer Series, Waltham, MA, USA).

- pH-meter (Ohaus, Starter 2000, Parsippany, NJ, USA).

- Peristaltic pump with eluent speed regulation from 1 to 2 mL per min (Shenchen, SP-MiniPump01, Baoding, Hebei, China).

- Plate reader capable of measuring absorbance at 412, 414 nm (Tecan, Tecan Infinite 200 PRO, Männedorf, Switzerland).

- Timer (Fisher Scientific, Fisherbrand™ Traceable™ Big-Digit Timer/Stopwatch, Waltham, MA, USA).

- Tube rotator (ELMI, Intelli-Mixer RM-2S, Riga, Latvia).

- Vacuum pump (Bio-Rad, Vacuum Station, 1655004, Hercules, CA, USA).

3. Procedure

3.1. Reagent Preparation

3.2. H2O2 Concentration Measurement (10 min)

CRITICAL STEP. Establishing the exact concentration of the initial H2O2 stock is important because the yield of the product in the enzymatic synthesis of HOSCN (Section 3.7) is sensitive to this parameter.

CRITICAL STEP. Establishing the exact concentration of the initial H2O2 stock is important because the yield of the product in the enzymatic synthesis of HOSCN (Section 3.7) is sensitive to this parameter.- With the use of distilled water, dissolve 8.5 M H2O2 stock to a concentration with an expected OD240 of 0.5 (e.g., mix 1.35 μL of 8.5 M H2O2 with 998.65 μL of water).

- Read the absorbance of distilled water at 240 nm with a spectrophotometer.

- Read the absorbance of the H2O2 solution at 240 nm with a spectrophotometer.

- Subtract the background absorbance from the absorbance of the H2O2 solution.

- With the use of H2O2 molar extinction coefficient (43.6 M−1 cm−1) and the pathlength of light (e.g., 1 cm), calculate the concentration of the analyte.

- To find the concentration of the stock, multiply the obtained value by the dilution factor (e.g., multiply by 740.74 if diluted as described above).

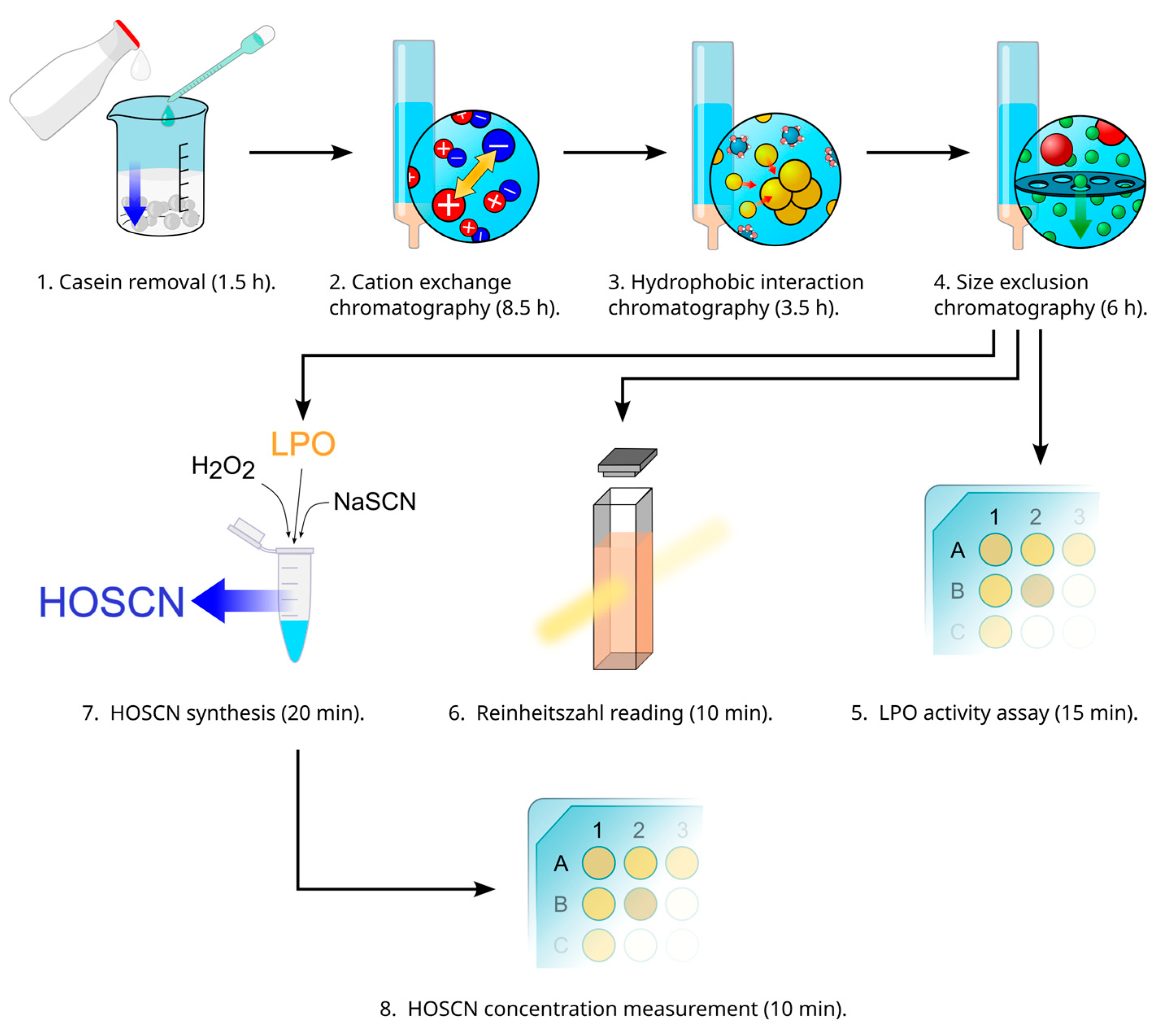

3.3. LPO Purification (1 h 30 min, 8 h 30 min, 3 h 30 min, 6 h)

3.3.1. Removal of Casein and Fat from Unpasteurized Bovine Milk (1 h 30 min)

- Defrost 1 L of bovine milk at 25 °C and transfer to a glass beaker cooled by melting ice.

- OPTIONAL STEP. A 1 mL sample of defrosted milk can be collected for the determination of LPO (ABTS-peroxidase assay, Section 3.4) and protein (e.g., Bradford assay) content.

- Under continuous mixing on a magnetic stirrer (80–100 rpm), add 30 mL of ice-cooled 1 M citric acid to milk. Add 1 mL of 1 M citric acid every 30 s (total time: 15 min).

- Transfer the obtained suspension to centrifuge tubes and centrifugate at +4–8 °C over 15 min at 2500× g in a bucket rotor.

- After centrifugation, with the use of a thin spatula, remove the upper layer of fat from the walls of the tubes.

- Separate the yellow-green supernatant of whey from the white sediment and transfer it to a glass beaker on ice.

- Repeat steps 4–6 with the obtained supernatant one more time.

CRITICAL STEP. If the membrane of the capsule filter contains azide as a preservative, it must be extensively washed by 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5) before whey filtration.

- To remove the residual traces of fat and casein sediment, filter the collected whey through a capsule membrane filter with a vacuum pump.

- To collect the residual whey, wash the filter with 55 mL of ice-cooled 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5), which corresponds to ~10% of the filtrated volume. Total time: 20 min.

- OPTIONAL STEP. A 1 mL sample of filtrated whey can be collected for the determination of LPO (ABTS-peroxidase assay, Section 3.4) and protein (e.g., Bradford assay) content.

3.3.2. Isolation of Cationic Proteins from Whey (8 h 30 min)

- Equilibrate the column with a strong cation exchanger resin (12 mL) by 3 volumes (36 mL) of ice-cooled 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5) with an elution speed of about 2 mL per min. Total time: 18 min.

- Load the filtrated whey on the equilibrated column with an elution speed of about 2 mL per min. The whey should be kept on ice. Total time: 5 h 10 min.

- Wash the column with 4 volumes (about 48 mL) of ice-cooled 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5), with an elution speed of about 2 mL per min. Total time: 24 min.

- If the last portions of the eluate are characterized by absorbance at 280 nm higher than 0.03, repeat elution by ice-cooled 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5).

- Start elution by a linear gradient from communicating vessels with 80 mL of ice-cooled 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5) and 80 mL of ice-cooled 4 M NaCl, 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The first solution should be continuously mixed by a magnetic stirrer. Keep the speed of elution at about 1 mL per min and collect 8 mL fractions to separate tubes on ice. Total time: 160 min.

- Combine the fractions with a green-brown color for the next step of LPO purification and store on ice.

- OPTIONAL STEP. The combined fractions can be collected for the determination of LPO (ABTS-peroxidase assay, Section 3.4) and protein (e.g., Bradford assay) content, as well as for Reinheitszahl calculation (Section 3.6).

3.3.3. Separation of LPO by Hydrophobic Chromatography (3 h 30 min)

- Add solid (NH4)2SO4 to the ice-cooled combined fractions obtained at the previous step of LPO purification: 1.189 g per 10 mL (final concentration should be 0.9 M). Mix thoroughly until salt dissolution. Total time: 30 min.

- Centrifugate the obtained suspension at +4–8 °C for 15 min at 2500× g in a bucket rotor.

- Collect the supernatant for LPO separation on a hydrophobic resin and keep on ice.

- Equilibrate the column with hydrophobic resin (5 mL) by 5 volumes (25 mL) of ice-cooled 900 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), with an elution speed of about 1 mL per min. Total time: 25 min.

- Load the collected supernatant on the equilibrated column with an elution speed of about 1 mL per min. Total time: 15 min.

- Wash the column with 5 volumes (about 25 mL) of ice-cooled 900 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), with an elution speed of about 1 mL per min. Total time: 25 min.

- If the last portions of the eluate are characterized by absorbance at 280 nm higher than 0.03, repeat elution by ice-cooled 900 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4).

- Start elution by a linear gradient from communicating vessels with 45 mL of ice-cooled 900 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 45 mL of ice-cooled 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The first solution should be continuously mixed by a magnetic stirrer. Keep the speed of elution at about 1 mL per min and collect 5 mL fractions to separate tubes on ice. Total time: 1 h 30 min.

- Combine the fractions with a green-brown color for the next step of LPO purification and store on ice.

- OPTIONAL STEP. The combined fractions can be collected for the determination of LPO (ABTS-peroxidase assay, Section 3.4) and protein (e.g., Bradford assay) content, as well as for Reinheitszahl calculation (Section 3.6).

3.3.4. Separation of LPO by Size-Exclusion Chromatography (6 h)

- For (NH4)2SO4 removal and final LPO purification, concentrate the combined fractions with MWCO 30 kDa ultrafiltration units until the final volume is 1 mL. Usually, 15 min centrifugation at 2500× g in a bucket rotor at +4–8 °C is enough for filtration of 10 mL.

- After centrifugation, dilute 1 mL of concentrated LPO to 10 mL by ice-cooled 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and keep on ice.

- Repeat concentration with ultrafiltration units.

- Equilibrate the column with size-exclusion resin with two volumes of ice-cooled 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Total time: 2 h 30 min.

- Load the concentrated sample of LPO on the equilibrated column and elute with 2 column volumes of ice-cooled 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Collect 2 mL fractions to separate the tubes and store on ice. Total time: 2 h 30 min.

- Combine the fractions with a green-brown color.

- Concentrate them to 1 mL with MWCO 30 kDa ultrafiltration units.

- OPTIONAL STEP. The combined fractions can be collected for the determination of LPO (ABTS-peroxidase assay, Section 3.4) and protein (e.g., Bradford assay) content, as well as for Reinheitszahl calculation (Section 3.6).

- Divide concentrated LPO to 200–500 μL aliquots in Eppendorf tubes and store at −80 °C.

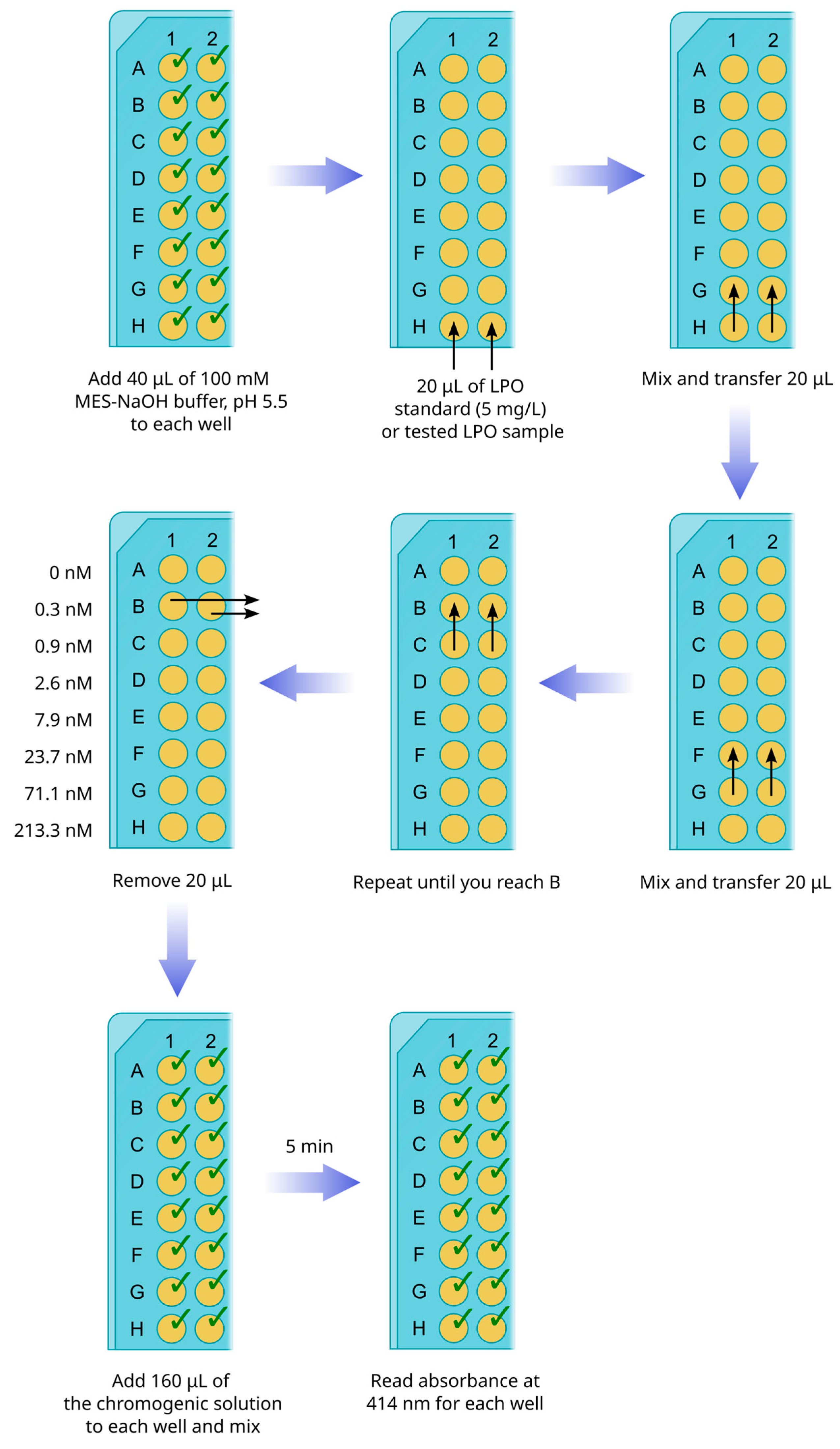

3.4. LPO Peroxidase Activity Assay with ABTS as a Chromogenic Substrate (15 min)

- Prepare 5 mg/L (or 640 nM) LPO standard: Add 1 μL of 100 μM LPO stock solution (1400 U/mg in guaiacol assay) to 1.56 mL of 100 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5, in an Eppendorf tube.

- Transfer 40 μL of 100 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5, to all 8 wells of a strip from a 96-well plate (Figure 2).

- Transfer 20 μL of LPO standard (5 mg/L) or 20 μL of a tested sample to the bottom line (H) of the strip.

- Mix the solution in line H by pipetting and transfer 20 μL to line F.

- Repeat mixing and transferring until you reach line B. In the end, 20 μL of the mixture must be removed from line B, and no diluted enzyme or tested samples should be transferred to line A. The latter is used as a negative control line (addition of the chromogenic solution to this well should not cause the development of a green color). Thus, the lines from H to B receive the series of dilutions from 3- to 2187-fold.

CRITICAL STEP. If tested samples of LPO, obtained after chromatographic fractionation, are visually olive-colored, they must be diluted at least 100 times before transferring to the bottom line (H) of the strip.

- Repeat steps 1–5 for the tested samples.

- OPTIONAL STEP. If tested samples are characterized by an intense olive color and give overvalues in ABTS-based assay, LPO concentration can be determined by reading absorbance at 412 nm (Section 3.6).

- Add 160 μL of the chromogenic solution to each well of the strips. Mix thoroughly by pipetting.

- After 5 min of incubation, read the absorbance of all wells at 414 nm with a plate analyzer.

- Plot a calibration curve describing the dependence of the sample absorbance on LPO concentration for the standard strip. Calculate concentrations of LPO in the tested samples, taking into account the dilution factors.

3.5. LPO Peroxidase Activity Assay with Guaiacol as a Chromogenic Substrate (10 min)

- Prepare 2 mg/L LPO in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4): Add 1 μL of 100 μM LPO stock solution to 37.8 μL of the buffer. Mix thoroughly. Then, take 2 μL of the resulting solution and mix it with 198 μL of the buffer. Keep on ice.

- In a 1 mL cuvette, mix 705 μL of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 250 μL of 100 mM guaiacol solution, and 5 μL of 50 mM H2O2 solution.

- Place the cuvette to a spectrophotometer. Set it ready to measure absorbance at 470 nm.

- Start the reaction by adding 40 μL of 2 mg/L LPO and mix it by pipetting several times.

- Record absorbance each 2–5 s for a minute.

- Plot the obtained data in any convenient software (e.g., Microsoft Excel LTSC 2024). Find the linear region of the curve and calculate its slope (ΔOD470/Δt).

- One unit of activity is the amount of enzyme that converts 1 μmol of guaiacol to tetraguaiacol per minute (U = μmol/min). With the use of tetraguaiacol molar extinction coefficient (26,600 M−1 cm−1) and the pathlength of light (1 cm), calculate the activity of the sample in U/L. Remember that one molecule of tetraguaiacol emerges from the oxidation of four guaiacol molecules.

- To normalize the obtained activity, divide it by the concentration of LPO in the cuvette (0.08 mg/L).

3.6. Reading Absorbance of LPO at 412 nm and Calculating Reinheitszahl (RZ) During Final Steps of LPO Isolation (10 min)

- Transfer 100 mM MES-NaOH buffer (pH 5.5) to a cuvette. Next, perform blank absorbance at 280 and 412 nm.

- Transfer 9 μM pure commercial LPO or a tested LPO sample to a cuvette. Next, measure absorbance at 280 and 412 nm.

- If the tested samples give overvalues, they should be diluted 4-fold or more to obtain absorbances between 0.7 and 1.6 at both 280 and 412 nm.

- Calculate the ratio between the absorbance at 412 and 280 nm.

- If this ratio is more than 0.9, use molar extinction coefficient ε412 = 112.3 mM−1 cm−1 or ε1% 412 = 13.9 to determine the LPO concentration. If not, the last step of LPO purification (Section 3.3.4.) should be repeated.

3.7. HOSCN Synthesis (20 min)

- Choose a buffer system (pH 6.6 or pH 7.4). For more details, go to Section 4 Expected Results.

- Precool a centrifuge to 5 °C.

- Prepare 250 μL of 4 μM LPO solution (1400 U/mg in guaiacol assay) in the buffer (e.g., mix 10 μL of 100 μM LPO and 240 μL of the chosen buffer). Place the tube on ice (Figure 3).

- Add 50 μL of ice-cooled 20 mM NaSCN and 20 mM H2O2 mixture. Gently mix by pipetting. Avoid bubbling.

- Incubate for 30 s.

- Repeat steps 4–5 four more times.

- To eliminate excess H2O2, add bovine liver catalase to the final concentration of 100 μg/mL or 200–500 U/mL (e.g., add 5 μL of 10 mg/mL catalase solution to 500 μL of the reaction mixture).

- If working with pH 6.6, immediately adjust pH to 7.4 via the addition of 4 μL 5 M NaOH in order to decrease HOSCN reactivity.

- Incubate on ice for 3 min.

- To obtain the low-molecular-weight fraction of HOSCN and salts, perform ultrafiltration with MWCO 10 kDa columns at 12,000× g, 5 °C for 10 min.

- Store the obtained filtrate on ice.

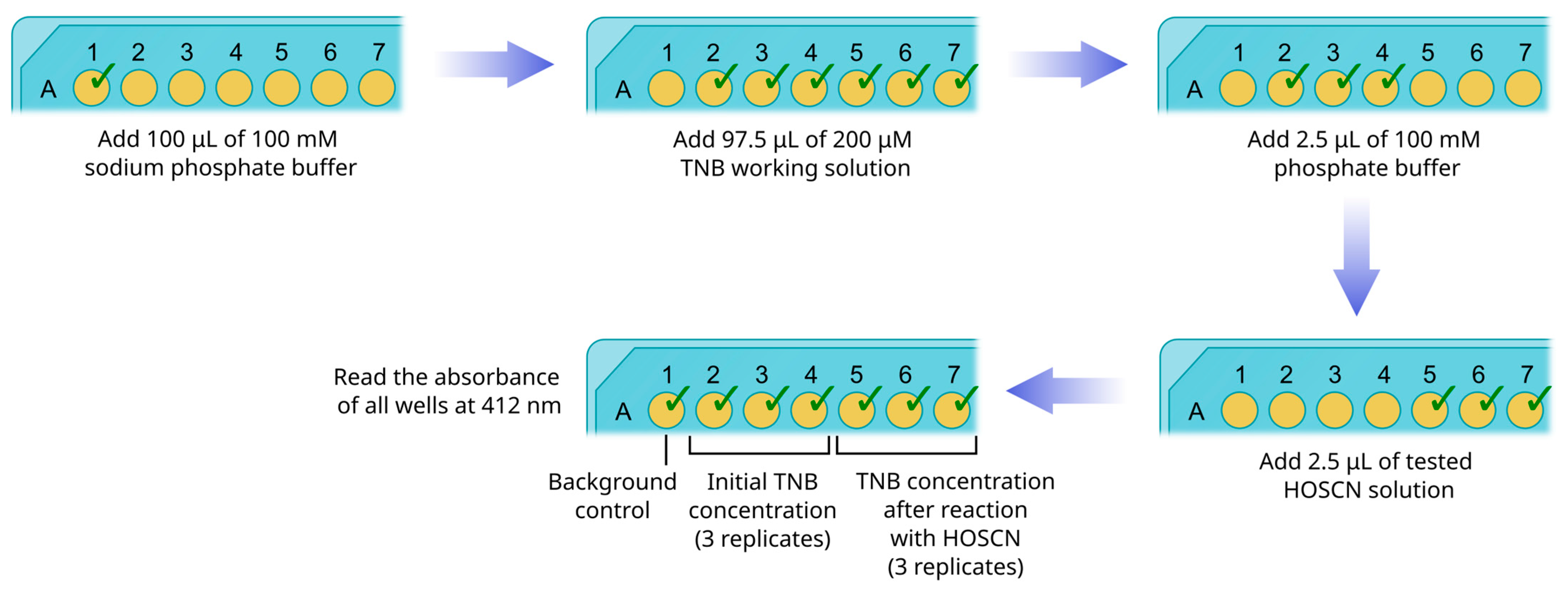

3.8. HOSCN Concentration Measurement (10 min)

- Transfer 100 μL of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to a single well (#1) of the plate (Figure 4).

- Transfer 97.5 μL of 200 μM TNB working solution to 6 wells (#2–7) of the plate.

- Transfer 2.5 μL of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to wells #2–4.

- Transfer 2.5 μL of tested HOSCN solution to wells #5–7.

- Thoroughly mix all solutions with pipetting. Avoid bubbling.

- Immediately read the absorbance of all wells at 412 nm with a plate analyzer.

- Subtract the optical density of well #1 from the optical densities of wells #2–7 to correct for background absorbance.

- Find mean values for wells #2–4 and #5–7.

- With the use of TNB molar extinction coefficient (14,150 M−1 cm−1) and the pathlength of light (0.28 cm) calculate the mean concentrations of TNB.

- Subtract the mean concentration of TNB in wells #5–7 from the mean concentration in wells #2–4. The difference between concentrations represents the amount of TNB consumed in the reaction with HOSCN.

- To find the concentration of HOSCN in the initial solution, multiply the obtained value by 20. This procedure takes into account both the 40-fold dilution of the sample and the fact that one HOSCN molecule oxidizes two TNB molecules.

3.9. Troubleshooting

3.10. General Notes

- There is experimental evidence for a possible non-enzymatic reaction between excess H2O2 and HOSCN, leading to the formation of byproducts such as cyanosulfurous acid (HOOSCN). HOOSCN is believed to be a more cytotoxic agent with a broader reactivity range than HOSCN [46]. This fact should be taken into account when planning and interpreting experiments modeling oxidative stress in cells.

- If a pH adjustment procedure is involved during HOSCN synthesis (Section 3.7, Step 8), we advise testing that the amount of NaOH added is sufficient for reaching the target value beforehand. It can be performed with a pH-meter in a large volume and recalculated for the desired volume of the synthesis.

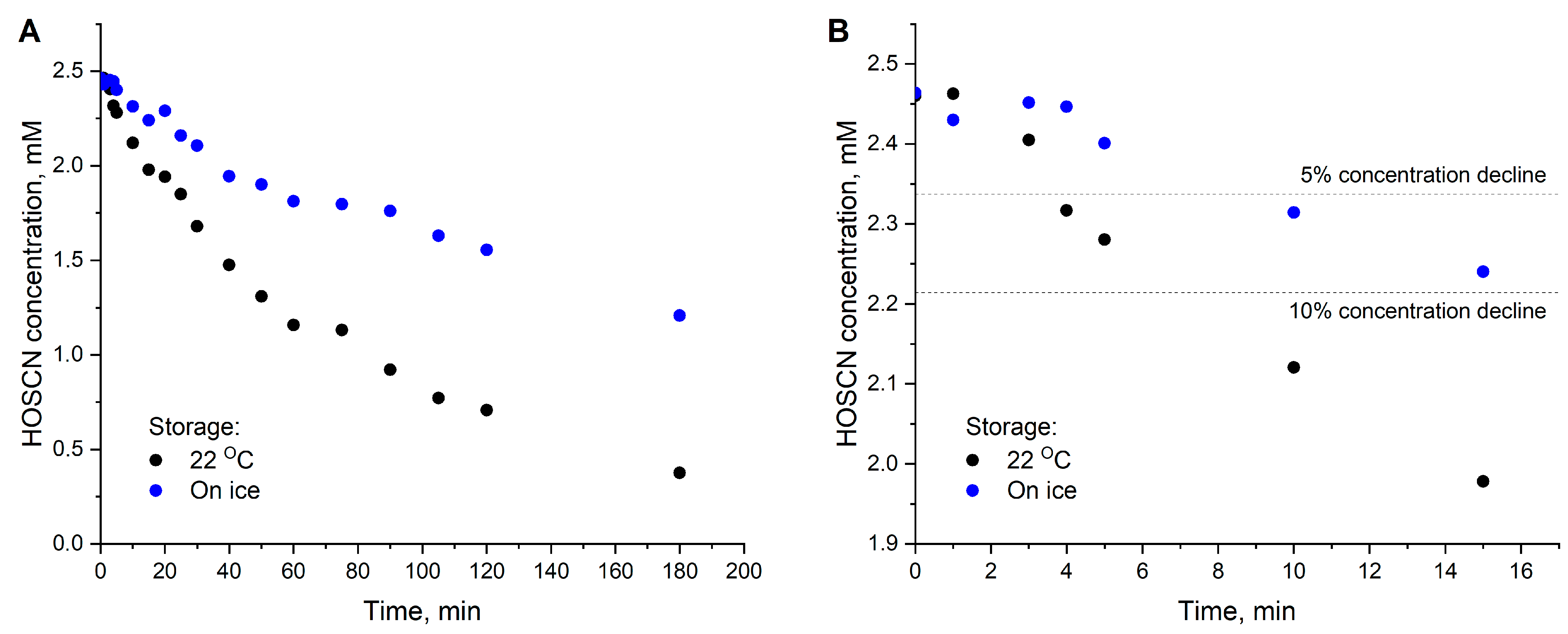

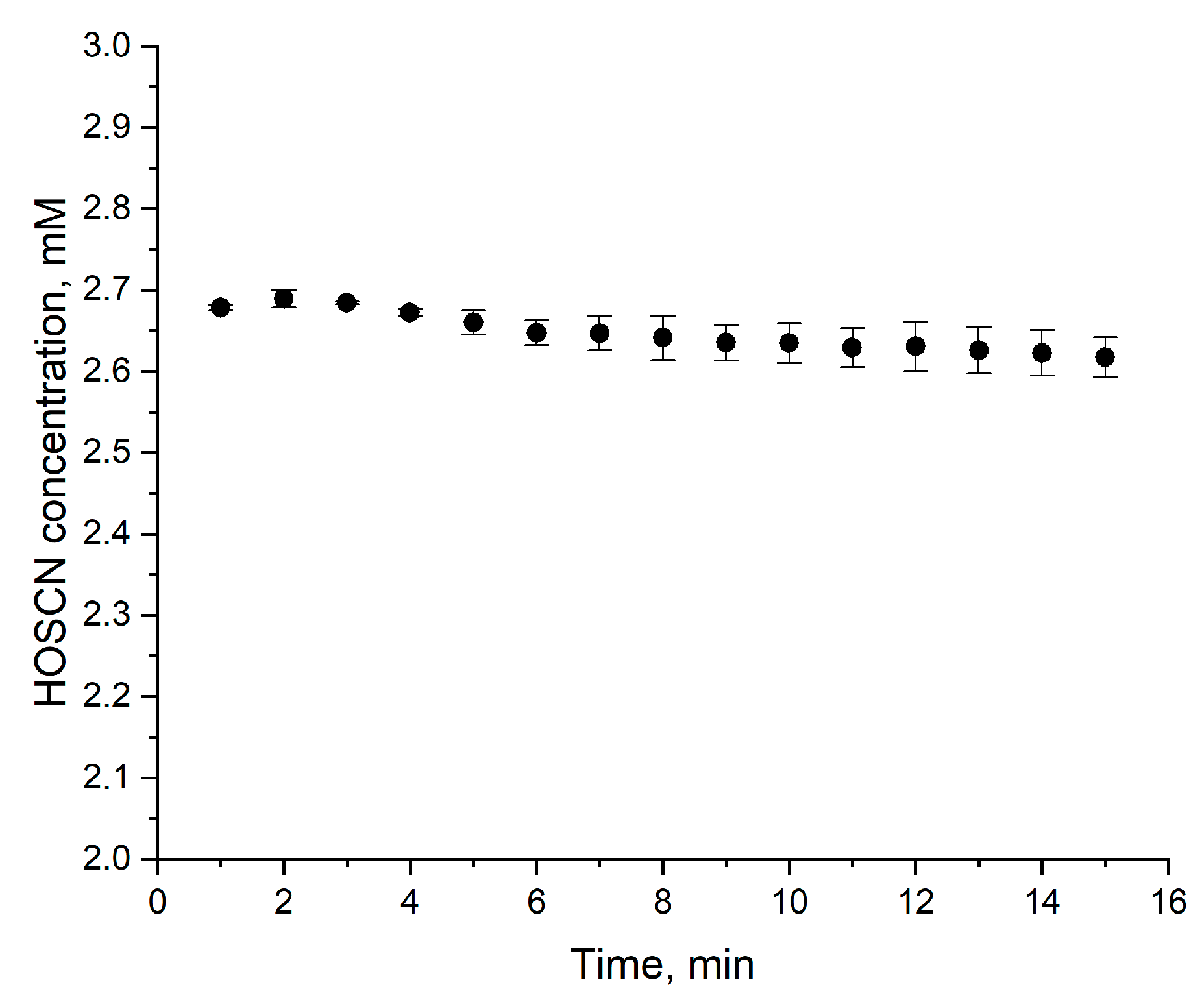

4. Expected Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azinobis-(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulphonic) Diammonium Salt |

| DTNB | 5,5-Dithio-bis-(2-Nitrobenzoic Acid) |

| KP | Potassium phosphate |

| LPO | Lactoperoxidase |

| MES | 2-Morpholinoethanesulfonic Acid |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| n/a | Not applicable |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| NaP | Sodium phosphate |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffer saline |

| RZ | Reinheitszahl |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TNB | 2-Nitro-5-Thiobenzoic Acid |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L.; Pattison, D.I.; Rees, M.D. Mammalian Heme Peroxidases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Health Implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1199–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Metodiewa, D. Reactivity of Biologically Important Thiol Compounds with Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storkey, C.; Davies, M.J.; Pattison, D.I. Reevaluation of the Rate Constants for the Reaction of Hypochlorous Acid (HOCl) with Cysteine, Methionine, and Peptide Derivatives Using a New Competition Kinetic Approach. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 73, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaff, O.; Pattison, D.I.; Morgan, P.E.; Bachana, R.; Jain, V.K.; Priyadarsini, K.I.; Davies, M.J. Selenium-Containing Amino Acids Are Targets for Myeloperoxidase-Derived Hypothiocyanous Acid: Determination of Absolute Rate Constants and Implications for Biological Damage. Biochem. J. 2011, 441, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.D.; Nichols, D.P.; Nick, J.A.; Hondal, R.J.; Day, B.J. Selective Metabolism of Hypothiocyanous Acid by Mammalian Thioredoxin Reductase Promotes Lung Innate Immunity and Antioxidant Defense. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 18421–18428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, J.D.; Chapman, I.; Ulrich, K.; Sebastian, C.; Stull, F.; Gray, M.J. Escherichia Coli RclA Is a Highly Active Hypothiocyanite Reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2119368119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, H.L.; Loi, V.V.; Weiland, P.; Bange, G.; Altegoer, F.; Hampton, M.B.; Antelmann, H.; Dickerhof, N. MerA Functions as a Hypothiocyanous Acid Reductase and Defense Mechanism in Staphylococcus Aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2023, 119, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van DALEN, J.C.; WHITEHOUSE, W.M.; WINTERBOURN, C.C.; KETTLE, J.A. Thiocyanate and Chloride as Competing Substrates for Myeloperoxidase. Biochem. J. 1997, 327, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, D.I.; Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. Reactions and Reactivity of Myeloperoxidase-Derived Oxidants: Differential Biological Effects of Hypochlorous and Hypothiocyanous Acids. Free Radic. Res. 2012, 46, 975–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilmohan, R.; Kettle, A.J. Bromination and Chlorination Reactions of Myeloperoxidase at Physiological Concentrations of Bromide and Chloride. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 445, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürmann, N.; Forrer, P.; Casse, O.; Li, J.; Felmy, B.; Burgener, A.-V.; Ehrenfeuchter, N.; Hardt, W.-D.; Recher, M.; Hess, C.; et al. Myeloperoxidase Targets Oxidative Host Attacks to Salmonella and Prevents Collateral Tissue Damage. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 16268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, D.I.; Davies, M.J. Reactions of Myeloperoxidase-Derived Oxidants with Biological Substrates:Gaining Chemical Insight into Human Inflammatory Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 3271–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.E.; Pattison, D.I.; Talib, J.; Summers, F.A.; Harmer, J.A.; Celermajer, D.S.; Hawkins, C.L.; Davies, M.J. High Plasma Thiocyanate Levels in Smokers Are a Key Determinant of Thiol Oxidation Induced by Myeloperoxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.T.; Carlson, A.C.; Scott, M.J. Redox Buffering of Hypochlorous Acid by Thiocyanate in Physiologic Fluids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15976–15977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, N.; Maghzal, G.J.; Talib, J.; Rashid, I.; Lau, A.K.; Stocker, R. The Roles of Myeloperoxidase in Coronary Artery Disease and Its Potential Implication in Plaque Rupture. Redox Rep. 2017, 22, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, Y.W.; Whiteman, M.; Cheung, N.S. Chlorinative Stress: An under Appreciated Mediator of Neurodegeneration? Cell. Signal. 2007, 19, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G. HOCl and the Control of Oncogenesis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 179, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.M.; van Reyk, D.M.; Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. Hypothiocyanous Acid Is a More Potent Inducer of Apoptosis and Protein Thiol Depletion in Murine Macrophage Cells than Hypochlorous Acid or Hypobromous Acid. Biochem. J. 2008, 414, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.M.; Grima, M.A.; Rayner, B.S.; Hadfield, K.A.; Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. Comparative Reactivity of the Myeloperoxidase-Derived Oxidants Hypochlorous Acid and Hypothiocyanous Acid with Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, D.T.; Guo, C.; Nikelshparg, E.I.; Brazhe, N.A.; Sosnovtseva, O.; Hawkins, C.L. The Role of the Myeloperoxidase-Derived Oxidant Hypothiocyanous Acid (HOSCN) in the Induction of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Macrophages. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.A.; Reszka, K.J.; McCormick, M.L.; Britigan, B.E.; Evig, C.B.; Patrick Burns, C. Role of Thiocyanate, Bromide and Hypobromous Acid in Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Apoptosis. Free Radic. Res. 2004, 38, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.E.; Laura, R.P.; Maki, R.A.; Reynolds, W.F.; Davies, M.J. Thiocyanate Supplementation Decreases Atherosclerotic Plaque in Mice Expressing Human Myeloperoxidase. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietzer, A.; Niepmann, S.T.; Camara, B.; Lenart, M.A.; Jansen, F.; Becher, M.U.; Andrié, R.; Nickenig, G.; Tiyerili, V. Sodium Thiocyanate Treatment Attenuates Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation and Improves Endothelial Regeneration in Mice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. Role of Thiocyanate in the Modulation of Myeloperoxidase-Derived Oxidant Induced Damage to Macrophages. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sileikaite, I.; Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. Myeloperoxidase Modulates Hydrogen Peroxide Mediated Cellular Damage in Murine Macrophages. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.T. Chapter 8—Hypothiocyanite. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; van Eldik, R., Ivanović-Burmazović, I., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 64, pp. 263–303. ISBN 0898-8838. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, P.; Alguindigue, S.S.; Ashby, M.T. Lactoperoxidase-Catalyzed Oxidation of Thiocyanate by Hydrogen Peroxide: A Reinvestigation of Hypothiocyanite by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Optical Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 12610–12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupp-Sutton, K.; Ashby, M.T. Reverse Ordered Sequential Mechanism for Lactoperoxidase with Inhibition by Hydrogen Peroxide. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenzer, H.; Kohler, H.; Broger, C. The Role of Hydroxyl Radicals in Irreversible Inactivation of Lactoperoxidase by Excess H2O2: A Spin-Trapping/ESR and Absorption Spectroscopy Study. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987, 258, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, I.A.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, N.; Sinha, M.; Singh, S.B.; Bhushan, A.; Kaur, P.; Srinivasan, A.; Sharma, S.; Singh, T.P. Structural Evidence of Substrate Specificity in Mammalian Peroxidases: Structure of the thiocyanate complex with lactoperoxidase and its interactions at 2.4 Å resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 14849–14856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, N.; Sharma, S.; Shin, K.; Takase, M.; Kaur, P.; Srinivasan, A.; Singh, T.P. Inhibition of Lactoperoxidase by Its Own Catalytic Product: Crystal Structure of the Hypothiocyanate-Inhibited Bovine Lactoperoxidase at 2.3-Å Resolution. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmár, J.; Woldegiorgis, K.L.; Biri, B.; Ashby, M.T. Mechanism of Decomposition of the Human Defense Factor Hypothiocyanite Near Physiological pH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19911–19921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenovuo, J.; Kurkijärvi, K. Immobilized Lactoperoxidase as a Biologically Active and Stable Form of an Antimicrobial Enzyme. Arch. Oral Biol. 1981, 26, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamaki, K.; Ueda, T.; Nagata, S. The Evolutionary Conservation of the Mammalian Peroxidase Genes. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2003, 98, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarr, D.; Tóth, E.; Gingerich, A.; Rada, B. Antimicrobial Actions of Dual Oxidases and Lactoperoxidase. J. Microbiol. 2018, 56, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, K.; Tomita, M.; Lönnerdal, B. Identification of Lactoperoxidase in Mature Human Milk. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2000, 11, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kussendrager, K.D.; van Hooijdonk, A.C. Lactoperoxidase: Physico-Chemical Properties, Occurrence, Mechanism of Action and Applications. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84 (Suppl. 1), S19–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Schulz, P.M.; Schaupp, C.; Jungbauer, A. Bovine Whey Fractionation Based on Cation-Exchange chromatography1Presented at the International Symposium on Preparative and Industrial Chromatography and Related Techniques, Basel, 1–4 September 1996.1. J. Chromatogr. A 1998, 795, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozonet, S.M.; Scott-Thomas, A.P.; Nagy, P.; Vissers, M.C.M. Hypothiocyanous Acid Is a Potent Inhibitor of Apoptosis and Caspase 3 Activation in Endothelial Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, E.; Hampton, M.B.; Smyth, L.C.D. Hypothiocyanous Acid Disrupts the Barrier Function of Brain Endothelial Cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L.; Kester, D.R. Hydrogen Peroxide Measurement in Seawater by (p-Hydroxyphenyl)Acetic Acid Dimerization. Anal. Chem. 1988, 60, 2711–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.S.; Van Trieste, P.F.; Garlick, S.M.; Mahon, M.J.; Smith, A.L. Ultraviolet Molar Absorptivities of Aqueous Hydrogen Peroxide and Hydroperoxyl Ion. Anal. Chim. Acta 1988, 215, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.P.; Kiesow, L.A. Enthalpy of Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide by Catalase at 25° C (with Molar Extinction Coefficients of H2O2 Solutions in the UV). Anal. Biochem. 1972, 49, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, R.W.; Gibson, Q.H. The Reaction of Ferrous Horseradish Peroxidase with Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 2409–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.L.; Morgan, P.E.; Davies, M.J. Quantification of Protein Modification by Oxidants. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, J.; Edlund, M.B.; Hänström, L. Bactericidal and Cytotoxic Effects of Hypothiocyanite-Hydrogen Peroxide Mixtures. Infect. Immun. 1984, 44, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slungaard, A.; Mahoney, J.R.J. Thiocyanate Is the Major Substrate for Eosinophil Peroxidase in Physiologic Fluids. Implications for Cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 4903–4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlandson, M.; Decker, T.; Roongta, V.A.; Bonilla, L.; Mayo, K.H.; MacPherson, J.C.; Hazen, S.L.; Slungaard, A. Eosinophil Peroxidase Oxidation of Thiocyanate: Characterization of major reaction products and a potential sulfhydryl-targeted cytotoxicity system. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaff, O.; Pattison, D.I.; Davies, M.J. Hypothiocyanous Acid Reactivity with Low-Molecular-Mass and Protein Thiols: Absolute Rate Constants and Assessment of Biological Relevance. Biochem. J. 2009, 422, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Suzuki, M.; Wakabayashi, H.; Hayama, K.; Yamauchi, K.; Abe, F.; Abe, S. Synergistic Anti-Candida Activities of Lactoferrin and the Lactoperoxidase System. Drug Discov. Ther. 2019, 13, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.E.; Tan, J.T.M.; Hawkins, C.L.; Heather, A.K.; Davies, M.J. The Myeloperoxidase-Derived Oxidant HOSCN Inhibits Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases and Modulates Cell Signalling via the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway in Macrophages. Biochem. J. 2010, 430, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, N.L.; Viola, H.M.; Sharov, V.S.; Hool, L.C.; Schöneich, C.; Davies, M.J. Myeloperoxidase-Derived Oxidants Inhibit Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+-ATPase Activity and Perturb Ca2+ Homeostasis in Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, J.; Kwan, J.; Suryo Rahmanto, A.; Witting, P.K.; Davies, M.J. The Smoking-Associated Oxidant Hypothiocyanous Acid Induces Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Dysfunction. Biochem. J. 2013, 457, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer Heather, L.; Kaldor Christopher, D.; Harry, H.; Kettle Anthony, J.; Parker Heather, A.; Hampton Mark, B. Resistance of Streptococcus Pneumoniae to Hypothiocyanous Acid Generated by Host Peroxidases. Infect. Immun. 2022, 90, e00530-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B. The Effect of Physiological Oxidants on the Amyloid Formation of the Tumour Suppressor Protein p16INK4a. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin North, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bozonet, S.M.; Magon, N.J.; Schwartfeger, A.J.; Konigstorfer, A.; Heath, S.G.; Vissers, M.C.M.; Morris, V.K.; Göbl, C.; Murphy, J.M.; Salvesen, G.S.; et al. Oxidation of Caspase-8 by Hypothiocyanous Acid Enables TNF-Mediated Necroptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, P.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Winterbourn, C.C. Kinetics and Mechanisms of the Reaction of Hypothiocyanous Acid with 5-Thio-2-Nitrobenzoic Acid and Reduced Glutathione. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 22, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray Michael, J. The Role of Metals in Hypothiocyanite Resistance in Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e00098-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.L. The Role of Hypothiocyanous Acid (HOSCN) in Biological Systems. Free Radic. Res. 2009, 43, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, S.; Deodhar, S.S.; Behere, D.V.; Mitra, S. Lactoperoxidase-Catalyzed Oxidation of Thiocyanate by Hydrogen Peroxide: Nitrogen-15 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Optical Spectral Studies. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, J.D.; Gray, M.J. Hypothiocyanite and Host–Microbe Interactions. Mol. Microbiol. 2023, 119, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reagent | Final Concentration | Quantity or Volume |

|---|---|---|

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | ||

| Na2HPO4·7H2O | 75 mM | 1.011 g |

| NaH2PO4·H2O | 25 mM | 170 mg |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 50 mL |

| Total | n/a | 50 mL |

| a. Adjust pH using dry phosphates, lab spatula, and pH-meter. b. Store at room temperature. | ||

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.6 | ||

| Na2HPO4·7H2O | 40 mM | 538 mg |

| NaH2PO4·H2O | 60 mM | 413 mg |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 50 mL |

| Total | n/a | 50 mL |

| a. Adjust pH using dry phosphates, lab spatula, and pH-meter. b. Store at room temperature. | ||

| 200 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | ||

| Na2HPO4·7H2O | 150 mM | 4.044 g |

| NaH2PO4·H2O | 50 mM | 680 mg |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 100 mL |

| Total | n/a | 100 mL |

| a. Adjust pH using dry phosphates, lab spatula, and pH-meter. b. Store at room temperature. | ||

| 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | ||

| 200 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | n/a | 5 mL |

| Distilled water | n/a | 45 mL |

| Total | n/a | 50 mL |

| a. Store at room temperature. | ||

| 4 M NaCl, 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | ||

| NaCl | 4 M | 23.376 g |

| 200 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | n/a | 10 mL |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 100 mL |

| Total | n/a | 100 mL |

| a. Store at room temperature. | ||

| 900 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | ||

| (NH4)2SO4 | 900 mM | 11.893 g |

| 200 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | n/a | 10 mL |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 100 mL |

| Total | n/a | 100 mL |

| a. Store at room temperature. | ||

| 100 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5 | ||

| MES·H2O | 100 mM | 10.66 g |

| NaOH | 20 mM | 400 mg |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 500 mL |

| Total | n/a | 500 mL |

| a. Adjust pH using dry MES·H2O and NaOH, lab spatula, and pH-meter. b. Store at +4 °C. | ||

| 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5 | ||

| 100 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5 | n/a | 10 mL |

| Distilled water | n/a | 90 mL |

| Total | n/a | 100 mL |

| a. Store at +4 °C. | ||

| 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5 | ||

| NaCl | 150 mM | 1.753 g |

| 100 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5 | n/a | 20 mL |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 200 mL |

| Total | n/a | 200 mL |

| a. Store at +4 °C. | ||

| 1 M citric acid solution | ||

| C6H8O7·H2O | 1 M | 21 g |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 100 mL |

| Total | n/a | 100 mL |

| a. Store at +4 °C. | ||

| 10 mM ABTS stock solution | ||

| ABTS | 10 mM | 55 mg |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 10 mL |

| Total | n/a | 10 mL |

| a. Store at +4 °C. | ||

| 10 mM H2O2 stock solution | ||

| 8.5 M H2O2 | 10 mM | 10 μL |

| Distilled water | n/a | 8.490 mL |

| Total | n/a | 8.5 mL |

| a. Store at +4 °C. | ||

| Chromogenic solution | ||

| 10 mM ABTS stock solution | 150 mM | 1.8 mL |

| 10 mM H2O2 stock solution | n/a | 0.9 mL |

| 100 mM MES-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5 | n/a | 15.3 mL |

| Total | n/a | 18 mL |

| a. Chromogenic solution can be stored in a dark place at room temperature for no more than 2 h. | ||

| 50 mM H2O2 stock solution | ||

| 8.5 M H2O2 | 50 mM | 5.9 μL |

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | n/a | 994.1 μL |

| Total | n/a | 1000 μL |

| a. Prepare right before the LPO guaiacol assay and do not store. | ||

| 100 mM guaiacol stock solution | ||

| 9.09 M guaiacol | 100 mM | 11 uL |

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | n/a | 989 uL |

| Total | n/a | 1000 uL |

| a. Guaiacol solution can be stored in a dark place at room temperature for no more than one week. | ||

| 50 mM NaOH solution | ||

| NaOH | 50 mM | 0.1 g |

| Distilled water | n/a | up to 50 mL |

| Total | n/a | 50 mL |

| a. Store at room temperature. | ||

| 8 mM TNB stock solution | ||

| DTNB | 5 mM | 2 mg |

| 50 mM NaOH solution | n/a | 1 mL |

| Total | n/a | 1 mL |

| a. Place the tube with solution to a rotator and mix on low speed for 30 min. In these conditions, alkaline hydrolysis of DTNB occurs and the expected concentration of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoic acid (TNB) is about 8 mM. Alternatively, you can vortex the tube for several minutes; however, the degree of hydrolysis will be lower. b. 8 mM TNB stock solution can be stored in a dark place at room temperature for a week without significant decline in the concentration. | ||

| 200 μM TNB working solution | ||

| 8 mM TNB stock solution | n/a | 25 μL |

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | n/a | 975 μL |

| Total | n/a | 1 mL |

| a. Prepare right before HOSCN concentration assay. b. 1 mL of 200 µM TNB working solution is sufficient for 9 wells in HOSCN concentration assay. c. 200 μM TNB working solution can be stored in a dark place at room temperature for no more than 3 h. | ||

| 5 M NaOH solution | ||

| NaOH | 5 M | 0.1 g |

| Distilled water | n/a | 500 μL |

| Total | n/a | 500 μL |

| a. Prepare right before HOSCN synthesis and do not store. | ||

| 200 mM H2O2 solution | ||

| 8.5 M H2O2 | 200 mM | 4 μL |

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 or 6.6 | n/a | 166 μL |

| Total | n/a | 170 μL |

| a. Prepare right before HOSCN synthesis and do not store. | ||

| 200 mM NaSCN solution | ||

| NaSCN | 200 mM | 32.8 mg |

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 or 6.6 | n/a | 2 mL |

| Total | n/a | 2 mL |

| a. Prepare right before HOSCN synthesis and do not store. | ||

| 20 mM H2O2 and 20 mM NaSCN solution | ||

| 200 mM H2O2 solution | n/a | 100 μL |

| 200 mM NaSCN solution | n/a | 100 μL |

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 or 6.6 | n/a | 800 μL |

| Total | n/a | 1 mL |

| a. Prepare right before HOSCN synthesis and do not store. | ||

| 10 mg/mL bovine liver catalase solution | ||

| Bovine liver catalase (2000–5000 U/mg) | 10 mg/mL | 1 mg |

| 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 | n/a | 100 μL |

| Total | n/a | 100 μL |

| a. Can be divided into 5 µL aliquots and stored at −20 °C for up to one month. | ||

| Step | Total Volume, mL | Total Protein, mg | Active LPO, mg | Purification, Fold | Reinheitszahl (A412/A280) | Yield, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defrosted milk | 1000 | 34,230 | 29 | 1 | - | 100 |

| Filtrate after fat and casein removal | 615 | 5320 | 28.7 | 6.4 | - | 99 |

| Eluate from cation-exchange chromatography (UNOSphere S) | 16 | 248 | 25.2 | 120 | 0.069 | 86.9 |

| Eluate from hydrophobic chromatography (Butyl-Sepharose FF) | 10 | 44.8 | 13.4 | 353 | 0.382 | 46.2 |

| Ultrafiltrate of eluate | 1 | 23.5 | 12.4 | 623 | 0.409 | 43.8 |

| Ultrafiltrate after size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200) | 1 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 1180 | 0.9 | 39.7 |

| Group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Protocol 1 | Protocol 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Protocols published in the literature | Protocols described here | ||||||||

| LPO (1400 U/mg in guaiacol assay), μM | 0.43 | 0.4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 5.16 | 2 | 2 |

| H2O2, mM | 0.287 | 1.25 | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3 | 3 | 2.4 | 5 | 10 | 10 |

| NaSCN, mM | 0.391 | 2 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 10 | 10 |

| NaSCN/H2O2 | 1.36 | 1.6 | 2 | 2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.125 | 1.3 | 1 | 1 |

| Additions, n | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Time between additions, min | n/a | 1 | n/a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Buffer | 10 mM KP, 67 mM Na2SO4 | 100 mM NaP | 10 mM KP | 10 mM KP | 10 mM KP | 10 mM KP | 10 mM KP | PBS | 100 mM NaP | 100 mM NaP |

| pH | 7.4 | 7.4 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 6.6 | 7.4 |

| Time before catalase, min | 5 | 1 | 15 | 10 | 1 | n/a | 10 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Catalase (2000–5000 U/mg), μg/mL | 1.6 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 10 | n/a | 30 | 30 | 100 | 100 |

| Temp, °C | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | ice | 22 | 22 | 22 | ice | ice |

| Mean yield, mM | 0.29 | 0.79 | 1.52 | 1.12 | 1.86 | 1.60 | 1.38 | 1.17 | 2.93 | 2.49 |

| Standard deviation, mM | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostyuk, A.I.; Oleinik, G.S.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Belousov, V.V.; Sokolov, A.V.; Bilan, D.S. An Optimized Protocol for Enzymatic Hypothiocyanous Acid Synthesis. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060144

Kostyuk AI, Oleinik GS, Mitkevich VA, Belousov VV, Sokolov AV, Bilan DS. An Optimized Protocol for Enzymatic Hypothiocyanous Acid Synthesis. Methods and Protocols. 2025; 8(6):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060144

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostyuk, Alexander I., Gleb S. Oleinik, Vladimir A. Mitkevich, Vsevolod V. Belousov, Alexey V. Sokolov, and Dmitry S. Bilan. 2025. "An Optimized Protocol for Enzymatic Hypothiocyanous Acid Synthesis" Methods and Protocols 8, no. 6: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060144

APA StyleKostyuk, A. I., Oleinik, G. S., Mitkevich, V. A., Belousov, V. V., Sokolov, A. V., & Bilan, D. S. (2025). An Optimized Protocol for Enzymatic Hypothiocyanous Acid Synthesis. Methods and Protocols, 8(6), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060144