Hydrofeminist Life Histories in the Aconcagua River Basin: Women’s Struggles Against Coloniality of Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Decolonial Feminist and Hydrofeminist Perspectives

3. Research Question and Objectives

Treating water as something quantifiable and instrumentalized not only carries the risk of its exploitation and deterioration, but also hides a management paradigm that is ultimately unfeasible and does not respond to the specific challenges of water, in specific places and at specific times. Abstraction is therefore another problem linked to issues of quantification, instrumentalization, anthropocentrism and nature/culture divide

4. Research Area

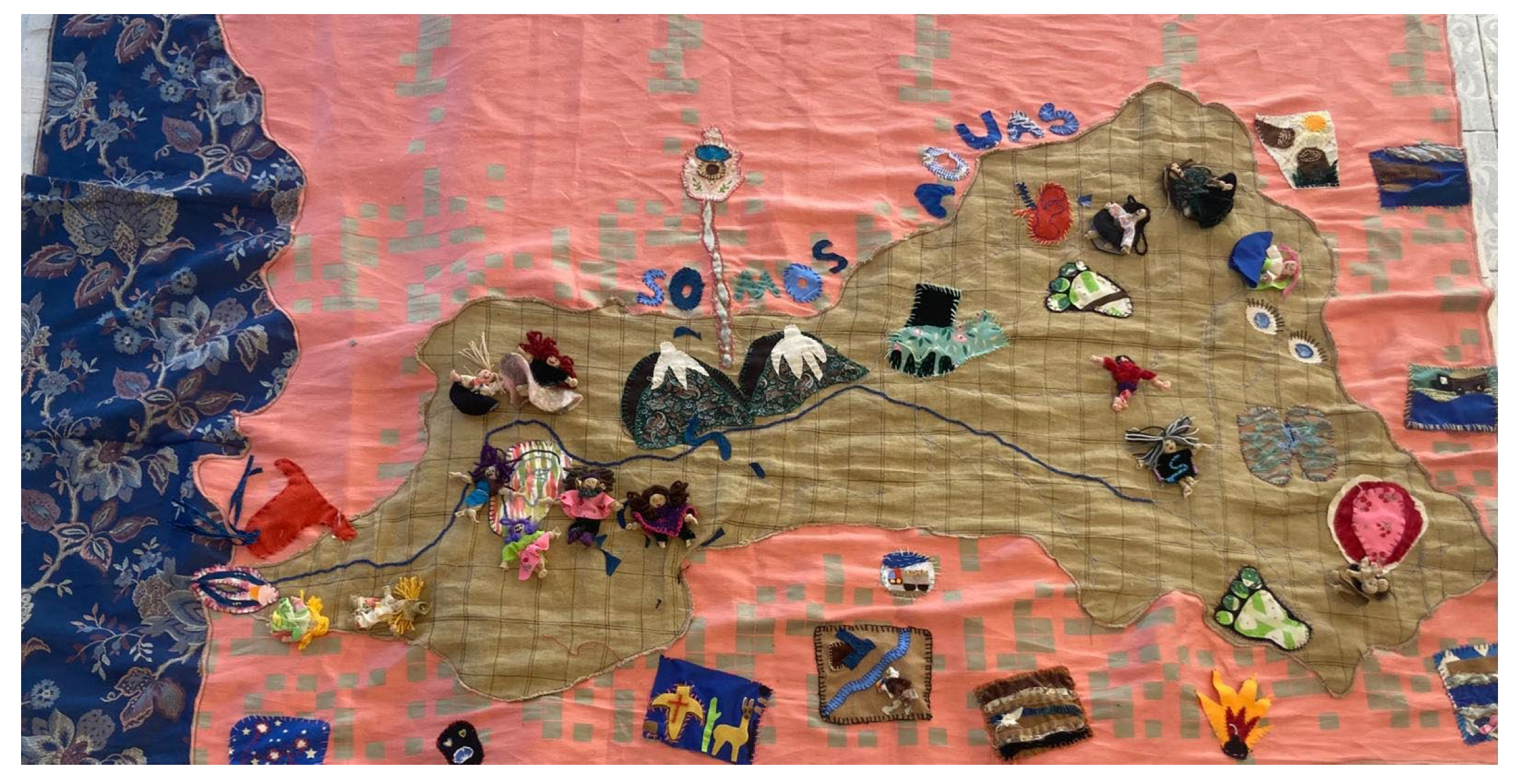

5. Research Methodologies

6. Results

6.1. Intersectionality of Violence

“Peasants, my grandparents and my great-grandparents, all have been engaged in agriculture. While, well, I think my dad stopped planting in 2012, more or less, planting the land. Because from then on I no longer had any water, and I was no longer old enough to go out to take care of the water, because we have the irrigation canal, which was intervened due to the destruction of aggregates, but then you had to wake up at night to be able to water the land for a couple of hours, so it was no longer a life for anyone, especially for an older adult, to have to wake up at 2 or 3 in the morning to be able to water.”(María, Limache, 2024)

“It was necessary for us to talk and find out what had motivated us and why we believed that we were the ones raising these issues and activating ourselves. Because we are all very powerful, so we said: yes, home care, which we have always had and which has also been for us as feminist women a whole issue, because the woman who stays at home is usually not valued for her work of upbringing, caring for parents, grandparents and everything. So, why do we have to take care of the land? In other words, how does this happen? We wanted to begin to unravel this among ourselves. We had all been motivated by essential issues such as water, not having water. Who is most affected by climate change? Women. Then we began to see that in all socio-environmental conflicts, the first to suffer are women.”(Francisca, Concón, 2024)

6.2. Environmental and Cosmogonic Coloniality

“There were fields where sources of employment were generated through tomatoes, potatoes, different basic food products, but today they are no longer seen. It is very lost and also due to the lack of water. Many times, when you ask them, why did they stop growing crops? They tell you ‘Because we don’t have water’. Or it is that the water is very concentrated in the big businessmen, or it is all going to avocados. So, this has also led to the loss of the agricultural identity here in the valley.”(Claudia, San Esteban, 2024)

“The defense of the wetland is more about water and the ecosystem, which is the most relevant. In other words, we don’t like to talk about natural resources or ecosystem services, we don’t like to say that because it is very anthropocentric. What we want to protect is the wetland that gives life to all of us. In other words, water gives life to all of us, not only to humans, but to all those who live there: flora, fauna, fungus. The important thing is to conserve it and we see that it is totally abandoned. A mouth is very important in a river, in a basin, and it is the most unprotected.”(Francisca, Concón, 2024)

“We have let ourselves be carried away by the industrialized, because now there is money. But, why do we have to defend water? Because water is vital, because without water there is no life. So, I do not understand why these people, with their ambition, do not have in their heads that water is a priority for human beings. Priority for human beings, not for mining or any other activity, even before the plants, we are human beings.”(Sandra, Putaendo, 2024)

6.3. Links Between Water Bodies

“I remember when I was a child, the weather was also like this, like now, that there is fog, that the sun comes out one day, the next day it doesn’t come out, that it had not rained for a long time in this weather. We used to go out with my sister to catch birds, at that time, we were all dirty, we used to go out in the middle of the mountains, catching birds with my sister, and there was also a lot of water back then. I used to say to my daughter, when I see the river, it makes me sad, because I saw that river was huge, in January, February, that river was huge. We used to bathe, it was not necessary to retire, we just had to go into the river, and we used to wash and play in the river.”(Luna, Los Patos, 2024)

“It was there that all this connection was linked to where I come from, to how good nature was to me. When I was little, nature welcomed me every day. I was very crafty, I didn’t want to eat at school. And I would come home and there were a lot of fruit trees and that’s what I ate. My mother didn’t know. I mean, every day I ate walnuts, peaches, that’s what I ate. I didn’t eat anything else. Nobody knew that I ate only what the land gave me.”(Margarita, Los Andes, 2024)

“I sometimes think that I have more water than blood. With my father, who was a miner, I always went to see the water above. So, since I was a child, I was aware of what water was, from a very young age. And then life put me on this path (to be president of the Rural Drinking Water Association), I always say that things happen for a reason.”(Sonia, Los Guzmanes, 2024)

“That is, I could not imagine any other life because I, for example, came home from school in the afternoon, alone in the summer, and I would go to the ravine. And I could spend the whole day bathing in the creek. That creek was formed by a snowdrift when the snow fell and those pools were next to it. So, for me, it was a world and I found it so beautiful and we used to go on trips when I was a child to the ravines because there in the mountains you didn’t have to pay for swimming pools, no. That is to say, you went to the ravines to swim. That is to say, one went to the ravines to bathe. So, that gives you a very close bond with nature and water. Unforgettable.”(Margarita, Los Andes, 2024)

6.4. Spirituality as Territorial Defense Strategy

“There is no defense for Mother Earth without connecting with all the spirits that inhabit her, right? Allies. That is, it is like asking them also to support us. That is to say, to connect with the Apu, with the spirits of the guanaco, with the condor, the pumas, with the spirit of the river and everything that surrounds us. Because it’s like, how are we going to be defending without connecting with them.”(Claudia, San Esteban, 2024)

“Since I was a child, I go up there every year. I go to Los Patos. If I don’t go to pray with people, I go alone and I make an offering up there for mother earth. I make an offering to the agüitas. I make offerings to the apus. I am always praying. I always pray upstairs.”(Sandra, Putaendo, 2024)

“The waters are not binary, they do not respond to the feminine or the masculine, and it is with this power of non-identification with binarism that I could with my identity, which did not fit into these categories. Gender is something that runs, it does not stop in rigid categories, just like the waters when no one stops them.”

7. Discussion and Final Reflections: Hydrofeminist Struggles for Water Justice

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aedo, María Paz. 2019. Afectos y resistencias de las mujeres de Chañaral frente a los impactos de la minería estatal en Chile. Sustentabilidad(es) 10: 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Aigó, Juana, Juan Carlos Skewes, Camila Bañales-Seguel, Wladimir Riquelme Maulén, Soledad Molares, Daniela Morales, María Ignacia Ibarra, and Debbie Guerra. 2020. Waterscapes in Wallmapu: Lessons from Mapuche perspectives. Geographical Review 112: 622–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabas, Alicia. 2010. El pensamiento sobre el territorio en las culturas indígenas de México. Avá. p. 1. Available online: https://argos.fhycs.unam.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/123456789/239/ava17_barabas_conferencia.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Bertaux, Daniel. 1981. Biography and Society: The Life History Approach in the Social Sciences. Beverly Hills: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bolados, Paola, and Alejandra Sánchez. 2017. A feminist political ecology under construction: The case of the” Women of sacrifice zones in resistance”, Valparaíso Region, Chile. Psicoperspectivas 16: 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolados, Paola, Fabiola Henríquez, Cristian Ceruti, and Alejandra Sánchez Cuevas. 2018. ‘La eco-geo-politica del agua: Una propuesta desde los territorios en las luchas por la recuperación del agua en la provincia de Petorca (Zona central de Chile)’. Revista Rupturas 8: 159–91. Available online: https://revistas.uned.ac.cr/index.php/rupturas/article/view/1977 (accessed on 8 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Boso, Àlex, María Fernanda Millán, Sánchez Galvis, and Luz Karime. 2024. Gobernanza comunitaria de sistemas de agua potable rural en un contexto altamente privatizado: Reflexiones a partir de caso de estudio en La Araucanía, Chile. Agua y Territorio 23: 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Budds, Jessica. 2009. Contested H2O: Science, policy and politics in water resources management in Chile. Geoforum 40: 418–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budds, Jessica. 2012. Water demand, evaluation and allocation in the context of scarcity: A hydro-social cycle analysis of the La Ligua river valley, Chile. Journal of Norte Grande Geography 52: 167–84. [Google Scholar]

- Budds, Jessica. 2020. Securing the market: Water security and the internal contradictions of Chile’s Water Code. Geoforum 113: 165–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabnal, Lorena. 2017. Tzk’at, Red de Sanadoras Ancestrales del Feminismo Comunitario desde Iximulew—Guatemala. Ecología Política 54: 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Calfuqueo, Sebastián. 2022. Bodies of water. In Aguas libres. Conversations with Artists and Activists for the Defense of Water in Abya Yala. Edited by María José Barros. Santiago: Editorial Ocholibros. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberly. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Curiel, Ochy. 2009. Decolonizing feminism: A perspective from Latin America and the Caribbean. Feminist theory and thought. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/75231/ochycuriel.2009.pdf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Damonte Valencia, Gerardo Héctor. 2015. Redefiniendo territorios hidrosociales: Control hídrico en el valle de Ica, Perú (1993–2013). Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 12: 109–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVault, Marjorie. 1999. Liberating Method: Feminism and Social Research. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, Giazú Encizo, and Alí Lara. 2014. Emotions and social sciences in the 20th century: The prequel to the affective turn. Athenea Digital. Journal of Social Thought and Research 14: 263–88. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, Arturo. 2003. Worlds and knowledges otherwise. The Latin American modernity/coloniality research program. Tabula Rasa 1: 51–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Arturo. 2016. Sentipensar con la tierra: Territorial struggles and the ontological dimension of southern epistemologies. AIBR: Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana 11: 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Espinal, Diana, and Ivette Peña Azcona. 2020. Ciencia y feminismo desde el cuerpo-territorio: En los estudios socioambientales. Géneroos 27: 301–22. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, Yuderkys. 2014. A decolonial critique of critical feminist epistemology. El Cotidiano 184: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1999. Los Condenados de la Tierra. Spain: Txalaparta. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Francisca. 2024. Feminismos Ecoterritoriales en América Latina. Santiago del Estero: Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Valentine. 2007. Theorizing and Researching Intersectionality: A challenge for Feminist Geography. The Professional Geographer 1: 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Raquel. 2014. Políticas en femenino. Reflections on the modern feminine and the meaning of its politics. In Más allá del feminismo, caminos para andar. Mexico City: Red de Feminismos Descoloniales. [Google Scholar]

- Hernando-Arrese, Maite, and María Ignacia Ibarra. 2025. Waters of resistance: Decolonising perspectives on women’s territorial r-existence in southern Chile. Gender & Development 33: 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, Yayo. 2021. Ecofeminist proposals for a debt-laden system. Revista De Economía Crítica 1: 30–54. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 2000. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. New York: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, María Ignacia. 2023. Critical, feminist and anti/pos/de/s/colonial approaches to understanding the world. Encrucijada Americana 15: 22–34. Available online: https://encrucijadaamericana.uahurtado.cl/index.php/ea/article/view/211 (accessed on 9 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, María Ignacia. 2024. Tumbar la blanquitud. Ensayos urgentes sobre raza y Colonialidad. Barcelona: Editorial Descontrol. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, María Ignacia, and Olga Jubany. 2024. The symbolic materiality of land from a gender lens: An intersectional analysis of Mapuche women’s oppressions, struggles and political strategies. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies 30: 323–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Alecia Youngblood, and Liza Mazzei. 2012. Thinking with Theory in Qualitative Research: Viewing Data Across Multiple Perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kerner, Ina. 2009. Beyond unidimensionality: Conceptualizing the relationship between racism and sexism. Philosophical Signs 11: 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, Mei Po, and Guoxiang Ding. 2008. Geo-Narrative: Extending Geographic Information Systems for Narrative Analysis in Qualitative and Mixed-Method Research. The Professional Geographer 60: 443–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, Edgardo. 2003. La Colonialidad del Saber: Eurocentrism and Social Sciences. Buenos Aires: CLACSO. [Google Scholar]

- Leff, Enrique. 2011. Diálogo de saberes, saberes locales y racionalidad ambiental en la construcción social de la sustentabilidad. In Saberes colectivos y diálogo de saberes en México. Mexico: UNAM, pp. 379–91. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, Jamie. 2010. What Is Water?: The History of a Modern Abstraction. Vancouver: UBC press. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, Jamie, and Jessica Budds. 2014. The hydrosocial cycle: Defining and mobilizing a relational-dialectical approach to water. Geoforum 57: 170–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugones, María. 2008. Colonialidad y género. Tabula Rasa 9: 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, Giulia. 2019. From the body in the territory to the body-territory: Elements for a Latin American feminist genealogy of the critique of violence. EntreDiversidades. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 13: 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Millanguir, Doris. 2017. Panguipulli: Historia y Territorio: 1850–946. Valdivia: Imprenta Austral. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, Chandra. 2008. Bajo los ojos de occidente. Academia Feminista y discurso colonial. Descolonizando el Feminismo: Teorías y Prácticas Desde los Márgenes 1: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Mario. 2019. Environmental racism: Slow death and dispossession of Afro-Ecuadorian ancestral territory in Esmeraldas. Íconos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 64: 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimanis, Astrida. 2014. Alongside the right to water, a posthumanist feminist imaginary. Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 5: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimanis, Astrida. 2017. Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology. London: Bloomsbury Academic, p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas-Artero, Chloé. 2016. Las organizaciones comunitarias de agua potable rural en América Latina: Un ejemplo de economía substantiva. Polis 15: 165–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortner, Sherry. 1981. Gender and Sexuality in Hierarchical Societies: The Case of Polynesia and Some Comparative Implications. In Sexual Meanings. Edited by Sherry B. Ortner and Harriet Whitehead. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2000. Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism and Latin America. Buenos Aires: CLACSO. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Patricia. 2016. Racismo: El modelo chileno y el multiculturalismo neoliberal bajo la Concertación, 1990-2010. Chile: Pehuén Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. 2018. Un mundo ch’ixi es posible. Argentina: Tinta Limón. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira, Guiomar. 2014. Encounters with the commonality of an outsider. Politics and life in the labyrinth. In Más allá del feminismo, caminos para andar. Mexico City: Red de Feminismos Descoloniales. [Google Scholar]

- Schiappacasse, Ignacio, Patricio Segura, and Joaquín Rozas. 2024. Social conflicts over the use of water resources in Chile: The role of social movements and business power. Oxford Development Studies 52: 381–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, Juan Pablo, and Felipe Tapia Valencia. 2017. El modelo de gestión comunitaria del agua potable rural en Chile: Contexto institucional, normativo e intenciones de reforma. Foro Jurídico 16: 110–20. [Google Scholar]

- Segato, Rita. 2003. Las estructuras elementales de la violencia: Ensayos sobre género entre la antropología, el psicoanálisis y los derechos humanos. Buenos Aires: Editorial Prometeo. [Google Scholar]

- Segato, Rita. 2015. The Critique of Coloniality in Eight Essays: And an Anthropology on Demand. Valencia: Editorial Prometeo. [Google Scholar]

- Segato, Rita. 2018. Counter-Pedagogies of Cruelty. Buenos Aires: Editorial Prometeo. [Google Scholar]

- Skewes, Juan Carlos. 2019. The Regeneration of Life in the Times of Capitalism. Santiago: Ocho Libros Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Skewes, Juan Carlos, and Debbie Guerra. 2004. The defense of Maiquillahue Bay: Knowledge, faith, and identity in an environmental conflict. Ethnology 43: 217–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Lise, and Sue Wise. 1993. Breaking Out Again: Feminist Ontology and Epistemology. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stipo, Camila. 2024. Caring for Life, Caring for Death: A Posthumanist Ethics of Care in the Face of Death in the Anthropocene. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/202448 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Svampa, Maristella. 2010. Towards a grammar of struggles in Latin America: Plebeian mobilization, demands for autonomy and eco-territorial turn. International Journal of Political Philosophy 35: 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ugarte, Paula. 2003. Derecho de Aprovechamiento de Aguas: Análisis histórico, extensión y alcance en la legislación vigente. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa, Astrid. 2021. Repoliticizing life, defending body-territories and collectivizing actions from indigenous feminisms. Ecología Política 61: 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Verea, Soledad, and Sofía Zaragocin. 2017. Feminismo y buen vivir: Utopías decoloniales. Ecuador: Universidad de Cuenca. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 2004. Perspectival anthropology and the method of controlled equivocation. Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Catherine. 2009. Critical interculturality and de-colonial pedagogy: Proposals (des) of in-surfacing, re-existing and re-living. UMSA Revista (Entre Palabras) 3: 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Catherine. 2010. Critical interculturality and intercultural education. Cuadernos de Educación Intercultural 8: 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2017. World Health Statistics 2017. Monitoring Health for the SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241565486. [Google Scholar]

- Zwarteveen, Margaret, and Vivienne Bennet. 2005. The connection between gender and water management. In Opposing Current Politics of Water and Gender in Latin America. Edited by Vivienne Bennet, Sonia Davila Poblete and Mania Nieves Rico. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibarra, M.I. Hydrofeminist Life Histories in the Aconcagua River Basin: Women’s Struggles Against Coloniality of Water. Histories 2025, 5, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5030031

Ibarra MI. Hydrofeminist Life Histories in the Aconcagua River Basin: Women’s Struggles Against Coloniality of Water. Histories. 2025; 5(3):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5030031

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbarra, María Ignacia. 2025. "Hydrofeminist Life Histories in the Aconcagua River Basin: Women’s Struggles Against Coloniality of Water" Histories 5, no. 3: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5030031

APA StyleIbarra, M. I. (2025). Hydrofeminist Life Histories in the Aconcagua River Basin: Women’s Struggles Against Coloniality of Water. Histories, 5(3), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5030031