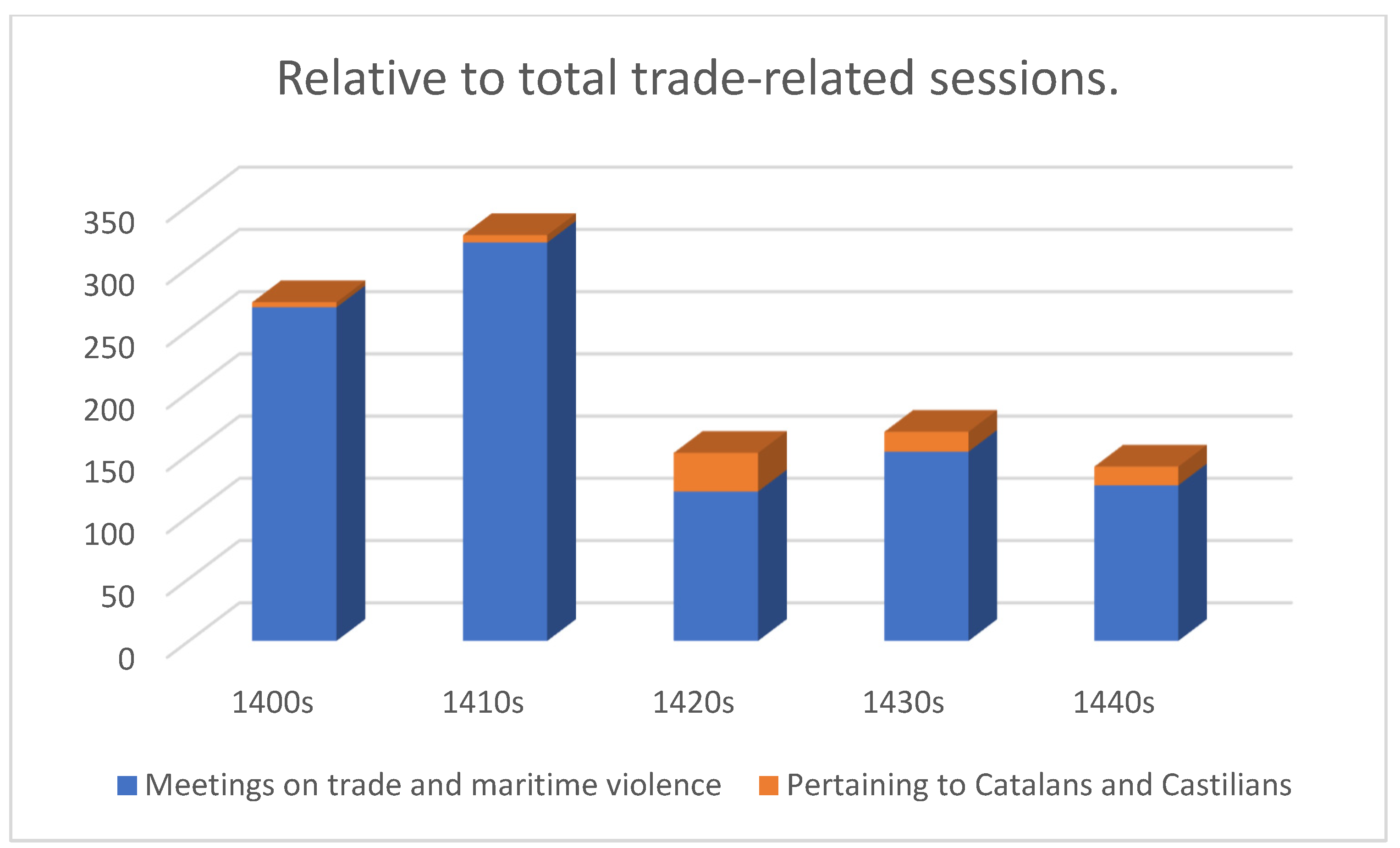

The Castilian and Catalan trading communities in Bruges faced a similar commercial hurdle during the first half of the fifteenth century, with punitive taxes amounting to 5% of the value of Castilian trade and 2.5% of the value of Catalan trade. Both taxes were justified by making explicit reference to maritime violence and plunder, whilst diplomatic talks displayed a willingness, from Bruges and the Duke, to avoid what would be a damaging cycle of reprisals (the forcible seizure or damage of goods and persons in response to a previous transgression).

4.1. A Tax on Castilian Commerce: The 20th Penny

The Castilian tax, claiming every twentieth penny, or a five percent duty on Castilian imports to Bruges(such as merino wool, salt, alum, and iron) was imposed by Duke Philip the Good in 1421. He justified the tax by citing the aggressive behaviour of the Castilians since 1417 and the damage they had wrought on Flemish commerce. That was the official line. What also played a role were the complaints made by the Hansard merchants in Flanders, featuring in the agenda of the Flemish Members in the build-up to and during this tax (HLS III, 17, 25).

This Castilian tax has been treated before, notably by Jules Finot and Jacques Paviot (

Finot 1899;

Paviot 1995). In Finot’s case, it is limited to the mentioning of the tax still animating discussions in the 1440s, despite Philip rescinding it in 1428. With that rescindment, the Duke also suspended letters of marque that legitimated counter seizures targeting Castilian shipping. This was done at Bruges’s request, citing difficulties in applying the tax to the correct people. In other words, the wrong people were being caught in the diplomatic and reprisal crossfire (Gilliodts-Van Severen 1907, p. 693;

Finot 1899, pp. 172–73). Finot’s account is brief but it does tell us that the tax controversy continued well into Philip’s reign.

Paviot went into more diplomatic depth, tracing the friction between the Flemish and the Castilians going back to at least the latter defeating the Hansard salt fleet off La Rochelle in November 1419. Bruges’s accounts confirm that Flemish merchants also suffered losses, with at least 12,000 lb gr. needed to compensate them. Additionally, the

Hanserecesse mention the loss of 40 ships, resulting in a further 25 not daring to sail out. In fact, the Hansards also organised so-called ‘peace ships’, financed by an internal toll in Bruges, to secure their trade to and from the city. As a result, the Members of Flanders decided to send an embassy to King Juan II of Castile (r. 1406–1454). Crucially, Finot and Paviot wrote, the Castilian merchants threatened to leave Bruges in the event of reprisals, a ‘costly signal’ that was credible given the availability of alternative ports in Zeeland and Brabant, thereby necessitating direct diplomatic contacts at the highest level. Upon the return of the ambassadors sent to conduct the talks with the Castilian King, Bruges suggested a tax to compensate the damages caused between 1417 and 1421. This was a five percent addition, in total merchandise valuation, to the Castilians’ enforcement costs; their access and safe-conduct now depended on the payment of this supplementary fee. This tax was imposed by the Duke in 1421. Now new issues arose, relating to enforcing the tax and continued acts of Castilian maritime harassment, leading to Flemish and Hansard reprisals. Finally, in 1427, a boiling point seemed to have been reached as the Castilian King—heavily lobbied by his merchant community which now had to bring more resources to bear in bargaining for unfettered market access—instructed his subjects to cease their trading activities in Flanders. The transaction costs were unacceptable to the Castilians. As a result, and after consultations with Bruges, the Duke felt obliged to rescind the tax in 1428 (SAB, Stadsrekeningen, 1422–1423, f. 82v; 1423–1424, f. 82v; 1419–1420, 88r. On the compensation, which was initially to be raised by Flanders from its own fiscal resources, see Stadsrekeningen, 1419–1420, f. 92v-93r; HR VI, 348; HR VII, 142, 288;

Paviot 1995, pp. 216–17;

Fieremans 2023, pp. 159, 357–58;

Stabel 2006, pp. 99–102).

The literature does not tell us the whole story, however. We know from a ducal decree that by 1418 the reparations issue was already on the Flemish commercial agenda. Moreover, the Bruges city accounts point to Flanders already footing the bill of Hansard damages suffered in Flemish waters. Whether these were directly related to the Castilians, however, is unclear. We do know that already in 1417, the

Hanserecesse mention the necessity to equip ‘peace ships’ to combat sea robbers. On the Castilian issue, it would take until 1421 for all wares originating from regions under Castilian control to be subjected to the tax (see

Table 1), signalling not just intent but forceful action. Castilian access to the Bruges market was now fiscally conditioned, constituting an increase in transaction costs; Flanders and the Duke felt it was necessary to make the Castilians pay for their transgressions in order to ensure proper conduct and protect both Hansard and Flemish commercial interests (SAB, Groenenboek A, f108r). It also came after the Members granted letters of marque and reprisal with ducal permission. This discomforted the Castilian traders in Bruges. Their threat to withdraw from the city soon followed. The tax was, therefore, likely viewed as a more sellable act of escalation, signalling discontent, albeit not constituting a full breakdown of commercial relations into a cycle of violent reprisals (Cartulaire de l’ancienne Estaple, 653; and Groenenboek A, f108r–108v). The decisions and motivations behind this subtle balancing act are, however, absent from the existing literature. This is important because a year earlier (1420) the Hansards had attempted to seize a Castilian ship in the

Zwin (a tidal inlet connecting Bruges to the sea), which they claimed was originally theirs (SAB, Stadsrekeningen, 1418–1419, f. 82v; 1419–1420, f. 87v, 88v, 95r-95v; HR VII, 165, 231). However, the situation did not descend into violent chaos between Hansards and Castilians off the Flemish coast. Diplomatic signalling, by the Duke, Bruges, and the Castilians, played a role in this regard.

Crucially, the decision to issue the tax was made by the Duke, at the request of the Members and Bruges in particular, who convened five times over the course of 1420 to discuss an embassy sent to Castile and complaints by the Hansards about the Castilians. These complaints related to the infringement of their privileges, specifically the safe-conduct safeguarding their lives and goods in the wake of what had happened off La Rochelle and continued tensions in the Zwin inlet. They felt they were entitled to reprisal as the behavioural contract had been violated. In the spring of 1420, an agreement was reached between the Members and the Hanse, constituting a binding promise that a policy response would come. This signalled the Flemish commitment to placate the Hansards and punish Castilian transgression. Whereas the existing literature focusses on the tax as a punishment of Castilian behaviour, it is clear that the Duke’s response, and Bruges’ intercession, also involved placating interests and balancing demands. The game was, thus, afoot. In June that year, the Members reconvened with the Duke’s chancellor and Hansard representatives to discuss the content and form of the restitution. This resulted in an embassy sent to Castile (HLS III, 17, 25, 26, 27, 28; HR VII, 576). The actors involved were trying to find a compromise that would appease the angered Flemish and Hansard merchants, without chasing away Castilian trade from Bruges. A signal of anger at Castilian transgressions was transmitted, although also a willingness to prevent a cycle of maritime violence and the economic uncertainty that would entail.

Upon the embassy’s return from Castile, the emissaries submitted their report by the summer of 1421 to the Members and the Duke. This coincided with additional reports of damages done to certain Flemish skippers; a convenient reminder of the trepidations Flemish traders still had to endure (HLS III, 67). It also followed further complaints by both the Hansards and the Castilians regarding the lack of respect for their privileges, including their respective safe-conducts (SAB, Stadsrekeningen, 1421–1422, f 83v–84r). By 1422, the tax was already being raised, as evidenced by Member discussions revolving around the distribution of the income from the tax. These ranged from compensating those damaged to paying the wages of the receivers of the tax and covering the costs of the various embassies sent to Castile over the past few years (HLS III, 108, 113, 92, 96). These discussions on the implementation of the tax rather than its validity or possible repercussions are a clear indication that at least in Flanders, the ruling authorities were content with the measure and had moved on from discussing its merits and demerits to discussing redistribution and implementation. They had chosen the route of placating both damaged parties, despite continued complaints, and subjecting the collective of Castilian merchants trading with Flanders to a tax. The policy reaction was not as top heavy as the existing literature suggests; it was the outcome of squaring multiple interests. Notwithstanding the Duke’s crucial importance in taking this decision, it was a decision informed by Bruges. Crucially, the impact on the Castilians’ transaction costs either did not feature or was considered tolerable by the Duke and Bruges.

However, the tax was eventually rescinded in 1428 after the Castilian King ordered his merchants to leave Flanders in 1427 (see

Table 1). So how did we get to that point? The renewal of the Castilian safe-conduct came in the immediate aftermath of the imposition of the 20th penny; continued market access was fiscally conditioned. As far as the Members and the Duke were concerned, the tax had restored the behavioural contract, which meant that safe-conducts could be renewed and re-confirmed. Indeed, it seemed that the Castilians had come to terms with the tax as a permanent rather than a temporary feature of their trade in Bruges, with an agreement being reached by the spring of 1425 in La Rochelle, signalling their formal bilateral acceptance after yet another round of Hansard complaints (HR VII, 801, 802). The tax would be a fixed feature of the Castilians’ transaction costs, and specifically their cost of enforcement in the Bruges market.

However, in 1427, the Castilian King’s consent to the tax wavered. In February, the Castilian nation threatened a departure from Flanders, citing the 20th penny as the main culprit. This signalled that in fact this tax was more than just a nuisance to Castilian commercial interests, and that it had fundamentally recalibrated their transaction costs in the city for several years now—so much so that it was worth departing Bruges. That is to say, a ducal decision pushed them to the brink. The additional cost imposed by what Bruges and the Duke thought was a necessary measure to enforce proper conduct was too much for the Castilians to bear. It constituted a fundamental threat to the viability of their trade in Flanders, and this had to be communicated one way or another—in this case the signal of diplomatic brinkmanship. Negotiations were conducted by the Members with the Castilian merchant community “in order to keep them in the country, after being ordered by their king to return shortly […].” Moreover, the Hansards complained yet again that their ships were still being harassed by the Castilians. As a result, and indicating desperation on the part of the Flemish and the Duke, an agreement in principle was achieved swiftly to discuss the abolition of the tax. What is clear, however, is that in Flemish circles an understanding existed that this was a case of either–or; either they abolished the tax or the Castilians left (HLS III, 275, 274, HR VIII, 17). The Castilians’ signal was clear; the ducal decision to tax their trade had pushed them to the brink.

It fell to the Duke’s chancellor and the Flemings to figure out how a Castilian departure could be avoided. Reports of Castilian and English harassment of Flemish commercial interests reappeared, straining relations and raising the possibility of whether arresting Castilian and English persons and their goods would be a proportionate reaction. The Members were clearly skating on thin ice. The signal this would send, right in the middle of (re)negotiations on the 20th penny, with the expenditure of scarce bargaining resources (the Castilians had already threatened to leave) to fix relations, would be explosive. Instead, it seems that a decision had been made to arrest a singular Castilian ship as reprisal rather than resort to a collective measure (HLS III, 277, 279, 282, 297). The limited form of punishment was again to prevent overly aggravating a Castilian nation that was on the verge of quitting Bruges. Using a ‘costly signal’ had its limits.

By the summer of 1428, the Castilians had leveraged their brinkmanship with a formal request for a revision of their privileges. The reason for the Castilian threats was now clear enough. Their request included a renewed safe-conduct, and of course a rescinding of the 20th penny. This was a clear example of diplomatically pushing back against an increase in transaction costs. The result was a new set of privileges for the Castilian nation. One should, however, mention a caveat; the aldermen of Bruges had insisted the 20th penny would remain in place (HLS III, 315; Cartulaire de l’ancienne Estaple, 694; Groenenboek A, f. 187v; and Cartulaire de l’ancien Consulat, 23). Bruges, perhaps, considered the tax to be vital in two respects: firstly, compensating Hansards and Flemish skippers and traders for their losses at the hands of the Castilians, thereby portraying itself as a benign manager of its market; secondly, as leverage over the Castilian nation. Alas, the final decision lay with the Duke, whose importance in decisively impacting this affair could not be clearer, and with it also proof of his importance in managing commerce.

Thus, 1428 was a watershed year. The Duke decided to rescind the tax, after initial lobbying by Bruges which itself had been pressured by Castilian threats and complaints, or negative signals, about their market access. After two years of talks, a draft trade agreement was reached in September 1428, including the privilege of Castilian consular jurisdiction in Bruges. This agreement granted the Castilian merchants the power to have their own consul adjudicate their internal commercial disputes, and had been drawn up by the Members and the Castilian ambassador. It was then proposed to the Duke, his chancellor, and members of the ducal council. The city, prince, and court of justice were signing off on an agreement that legally emancipated a group of merchants they until recently taxed on account of maritime transgressions. This was an agreement those very same perpetrators had co-authored. This was a peculiar development, indicating successful negotiating and employment of bargaining resources on the part of the Castilians. By 1430, the details had been ironed over (HLS III, 325, 326, 327, 331, 351, 428, 429, 431, 432, 433, 434, 435, 436;

González Arce 2010, p. 173). The city of Bruges considered the punitive tax necessary to an extent, be it for the financial restitution of the victims or as a signal towards the Castilians to tuck their tails in for the foreseeable future. It did so while fully aware of Hansard agitation with the lack of violent reprisals (HR VII, 576, 800, 802; VIII, 63, 66).In the end, however, the city crucially agreed to table the issue with the Duke despite opposing its rescindment.

The 20th penny tax was an attempt at bringing the Castilians back into the fold of trustworthiness, after the losses they had inflicted on the Hansard trading fleet and Flemish commercial interests, whilst raising the funds necessary to compensate those damaged by maritime transgressions. This topic quickly dominated the Flemish commercial diplomatic agenda, with the Castilians and Flemings expending ample bargaining resources to get to an agreement, eventually resulting in the tax’s rescindment a mere seven years after its introduction. In this story, by looking at diplomatic signals, the city of Bruges appears as a mediator, attempting to balance the sometimes contradicting interests of its foreign merchant communities, navigating a commercial landscape ultimately shaped by the Duke’s normative and fiscal frameworks. Ultimately, however, the decision to introduce and rescind the tax remained with the Duke, although he did not act without input from Bruges and repeated Hansard complaints, as well as, crucially, Castilian brinkmanship. In fact, enforcement and bargaining costs were a part of this story, motivating policy decisions and diplomatic signals by all parties.

4.2. A Tax on Catalan Commerce: Foul Play?

In 1442, Bruges sent a rider to the Duke’s central chamber of accounts in Lille, regarding the protection of the “arrest done on the goods of the Catalans” (SAB, Stadsrekeningen, 1442–1443, f 46v). This referred to a second tax controversy, this time on Catalan imports, which played out in the 1440s (see

Table 2). The existing historiography on the Catalans in the late medieval Low Countries highlighted their relative ‘invisibility’ in the general literature on trade in fifteenth century Flanders (

de Boer 2010, p. 246). Nevertheless, some scholars have tried to amend this problem. Desportes Bielsa, in his article on the Catalan consulate in Bruges, only mentions this tax contextually, explaining Bruges’s involvement in its negotiation by pointing out that commerce dictated the city’s policy standpoints. The Duke, in contrast, was an absent spectator only moved to action by his subjects (

Desportes Bielsa 1999, pp. 375–90).The why and how of this problematic period of Catalan–Flemish trading relations are left to the side.

According to Pifarré Torres, one can discern a peak of Catalan–Flemish trade in the late fourteenth century. By 1452, however, there were only five Catalan merchants present in Bruges, not because Bruges was entering a disastrous dynamic of decline but because Catalonia itself was at a relative commercial nadir (

Maréchal 1951, p. 27). Pifarré Torres places this major contraction of the fifteenth century later, after 1462, with the onset of civil war in Aragon (

Pifarré Torres 2002, p. 24). In contrast, de Boer questions whether the signs or even symptoms abroad of this crisis of Catalan trade can be discerned earlier, a view this article corroborates by pointing to the punitive tax imposed in 1440. Studying the 1450s and 1460s, de Boer sheds light on issues faced by Catalan traders in Flanders, the

fets (deeds or facts), revealing Duke Philip the Good, from a Catalan perspective, as a man who “does many large annoyances” and does so “contrary to every law” (

de Boer 2010, p. 256). The complaints related to their rights being infringed, safe-conducts being violated, the seizure of goods, and the rejection and delay of claims of compensation. In response, an embassy was sent by Barcelona and the Aragonese King to end these “vexations”, with the focus being on the safe-conduct and an exemption from right of shipwreck. The diplomatic efforts were evidently successful, as testified by the 1461 general safe-conduct and freedom of shipwreck granted by the Duke (

de Boer 2010, pp. 246–47, 256–59, 264, 268;

Maréchal 1951, p. 27;

Lambert 2011, p. 197). In short, the 1450s and 1460s were a period of particular stress for Catalan trade in Flanders.

This article finds that the traces of the original decline in trading contacts between Catalonia and Flanders even pre-existed the

fets de Boer studied, and that this has to do with the transaction costs of their trade. There were long-running frustrations among the Catalan traders that preceded the events leading up to a tax on their trade, originating in the 1430s, related to not being exempted from shipwreck fees and arbitrary confiscations. Moreover, maritime predation and the safe-conduct were on the agenda as well. In 1435 and 1436, English sea robbers captured Catalan ships off the Flemish coast. This was in breach of the safe-conduct (1414) the Catalans were supposed to enjoy in Flemish waters, notwithstanding their recent peace treaty that had been signed between Aragon and England (HLS II (1405–1419), 340, 343, 346;

Finot 1899, pp. 162, 164). Catalan trade in Flanders had clearly been under pressure for a while.

In 1438, during a session of the Members, an ‘arrest’ on Catalans was discussed. Pieter Van Campen, a merchant and Bruges alderman, had suffered from Catalan violence at sea. The arrest was opposed by Bruges, in order not to rile up a Catalan nation already facing stress. Just as in the Castilian case, Bruges signalled its willingness to act as a calming broker, underscoring its hitherto underrepresented role in these negotiations whilst underlining the Duke’s importance as key decision-maker. The case would reappear at a session of the Members in July the next year, this time summarised as “an agreement for restitution of damages by the Catalans”, and again in early 1440. The agreement encompassed a tax impacting the enforcement costs of Catalan trade. Later, a second ‘victim’ of Catalan transgressions was also named in these talks, ‘Lauwereins Noble’, otherwise identified as Laurent (le) Noble. By autumn, the Duke had ordered the Four Members to address the issue and accelerate decision-making, despite protests from the Catalan consuls in Bruges (HLS III, 696, 732, 763, 765, 781;

Lowagie 2011, p. 149).The game was afoot, and a tax was about to be raised on Catalan trade.

So what had happened? In 1436, a ship called the

Santa Maria de Saa, captained by a citizen of Sluis of Genoese origin, had been seized by the “Aragonese”. The vessel had left Sluis, Bruges’s outport, with a cargo of wheat and was destined for Catalonia, from whence it sailed on to Genoa. There, the captain of the ship left to continue his trade in Tunis before returning to Flanders again, the end-node. Off the Barbary Coast, however, he encountered a larger vessel belonging to subjects of the Aragonese Crown. This vessel started a pursuit of the

Santa Maria de Saa, which attempted to evade an altercation. Amid the panic, it floundered on the coast, resulting in its cargo being seized and the Genoese captain’s imprisonment. The reason for his arrest was that he had been accused of carrying goods for the Moors, enemies of the Aragonese King. Word of the events reached Bruges, implicating two individuals with an interest in the venture: Laurent le Noble, who was a member of the Duke’s close circle of friends and advisors; and Pieter Van Campen, a Bruges alderman. They decided to petition the Duke for justice, resulting in a flurry of letters sent to Barcelona, demanding the liberation of their business associate and the release of the merchandise he had been carrying. The authorities in Barcelona informed the Aragonese Queen, Maria of Castile, and the King of Navarra, Joan II, both acting in the stead of King Alfonso of Aragon (r. 1416–1458), who was away on campaign in Italy. Bruges also took on a role representing Catalan interests, likely being itself directly lobbied by Catalan consuls, merchants, and diplomats in the city. It appears that no decision was taken by the Aragonese authorities regarding the restitution of damages caused by this seizure, despite letters from the Duke and Duchess demanding action. Consequently, by July 1438, Duke Philip the Good had issued letters of marque to le Noble and Van Campen. These letters allowed them to enact reprisals, a ‘costly signal’, through the arrest and seizure of Catalans and their wares in Flanders, Brabant, Holland, and Zeeland. It was at that point that the Members, led by Bruges, decided to intervene and sway the Duke to embark on a different course of action. However, they only managed to delay the formal execution of these letters to August 1438 (HLS III, 763, 765, 868;

Paviot 1990, p. 122).

The letters signalled a willingness on the part of the Duke and the injured merchants to escalate the situation into a cycle of reprisal—a cycle Bruges had an interest in mitigating, just as with the Castilians, lest it spiral out of control. Again, the Duke did not take this decision in a vacuum, and faced various signals of support and opposition in the taking of this decision.

In Barcelona, the reaction to these letters sanctioning reprisal and arrest was one of panic, with another request to the King of Navarra, the co-regent, to intervene. He now provided a reason why restitution from their part was not in order; the seizure of the ship had been a legitimate act of war. In other words, the direct restitution out of Catalan–Aragonese coffers was out of the question, as it signalled a precedent that pulled legitimate acts of warfare into the realm of illegitimate maritime plunder. This line of reasoning remained uncovered and unexplained in the existing literature, although it is crucial in understanding why a decision to tax Catalan trade was made. Consequently, the Aragonese authorities ordered the Catalan merchants to leave Bruges for Antwerp, a commercial rival, as their safe-conduct had come under duress, thereby mirroring the ‘costly signal’ the Castilians had employed in the 1420s. It is in the shadow of that departure of Catalan trade from Bruges that Duke Philip created a commission to hear the complaints of le Noble and Van Campen, to estimate the damages and produce a proportionate response; that is to say, the Duke was looked upon yet again to enact a policy response. This then opened up the road to a tax to replace or accompany the letters of marque—a softer signal in intent and execution than acts of coercive maritime reprisal (

Paviot 1995, p. 214;

Desportes Bielsa 1999, p. 378).

Indeed, in 1440, the Catalans were subjected to a punitive tax, raising a levy on commerce coming from Catalonia (

Ferrer 2012, p. 48). It amounted to a 2.5% tax on the value of Catalan imports, and had been drawn up by the aforementioned commission. By the 14 March 1440, they had submitted a report, calculating the damages incurred by the Flemish plaintiffs as amounting to between 388 and 1288 lb. gr., resulting in a decision made by Flemish authorities to raise a tax of 1.65% on the value of Catalan trade. This was an additional strain on the enforcement costs of Catalan trade in Bruges; that is, until the Duke raised his own vexations, relating to the seizure of one of his caravels, which had allegedly been captured by the ‘Aragonese’ whilst en route to the Holy Land. Citing this as justification, Philip decided to raise the duty by an additional two groats to six in the pound in 1444 (to 2.5%), to be collected over a period of fourteen years. The receivers of this tax were none other than the well-connected Laurent Le Noble and Pieter Van Campen, the injured merchants we encountered earlier, rather than an independent receiver (

Finot 1899, pp. 187–89;

Paviot 1995, p. 214; Others serving on the commission were well-known officials such as Pierre Bladelin and Jan De Baenst. See

Dumolyn 2008b, pp. 67–92;

De Clercq et al. 2007, pp. 1–31. On De Baenst,

Buylaert 2005, pp. 42–43). This was a rather fortuitous—if not surprising, given the good relations between Philip and Alfonso of Aragon—turn of events for the Duke, who could now add his personal financial loss to those incurred by some of his traders (

De Clercq et al. 2015, pp. 153–71).

It is doubtful this tax increase was received with optimism in the Catalan camp; it constituted the second unilaterally imposed increase to their transaction costs in the space of four years. This was not exactly a signal of mutual trust and respect.

When justifying his actions between 1440 and 1450, the Duke cited the damages claim by le Noble and Van Campen as amounting to 3800 pounds. However, the commission set up to investigate damages came with a range of 388 to 1288 lb. gr.; the two claimants were not just recouping losses. This was a disastrous signal to send to the merchants frequenting Bruges’s market. In fact, the Duke mentioned that complaints started piling up, not just from Catalans but “unanimously” from other nations, likely referring to the confusion regarding who owned what and the inadvertent targeting of non-Catalan merchants. The complaints were serious enough for the Duke to admit it endangered Bruges’ commerce. He had entered a dangerous game of commercial brinkmanship. The merchants of Bruges also complained that the ship itself involved in the original seizure, the Santa Maria de Saa, was worth no more than 188 lb. 8s gr.—only a sixth of what had been raised so far via the punitive tax. Le Noble and Van Campen had been more than compensated, angering factions in Bruges, as well as abroad and at the ducal court, who feared the damage this tax was causing to the general trading environment (Gilliodts-Van Severen 1901, 40–42; SAB, Roodenboek, f. 150v.–154v). The Duke signalled his willingness to support and enact a fiscal measure that overshot its targets to compensate injured merchants who also happened to be politically influential. Moreover, its enforcement costs were no longer just hitting the Catalans but also Bruges’ trading community in general.

In his reasoning, Philip the Good was, thus, reflecting on his past action, citing the various complaints involving the Catalans, foreign merchants, and Bruges itself, linking it to the disproportionate nature of the return the tax was producing. Curiously, looking back on the decision-making process, he offered no mention of his own involvement in the matter. This was a convenient way of focussing the ire regarding a universally unpopular and commercially disastrous tax on two individuals, rather than himself. It is particularly notable since this was the second time that Philip the Good agreed to such a fiscal measure in punishing maritime violence by an Iberian trading group.

Some of these complaints passed by the Bruges court of law. Third-party merchants were apparently caught up in the tax. For example, the receivers of the tax, le Noble and Van Campen, had claimed payment of this “right” on several sacks of saffron imported by a Pierre Clavello, who in 1447 had refused to pay it since he claimed he sourced them from Genoa, not Barcelona. Bruges’s court cleared Clavello from any debt owed to the two receivers. In another case, the Catalan Saldone Ferrier contested the amount he was supposed to pay and agreed to go to arbitration over the issue. The arbiters agreed with Ferrier, a decision confirmed by the city court (Gilliodts-Van Severen 1907873, 933; SAB, Register Civiele Sententies (1447–1453), fol. 64r-v). This tax added to the enforcement costs, in money and time (and consequently opportunity costs), of Catalan and non-Catalan merchants alike. The tax was subject to contestation, with merchants trying to avoid paying it or contesting the amount, signalling distress at a collective punishment whose net seemed to be cast wider than was originally its purpose. The potential for a boiling-over point among the impacted merchant community is overlooked without looking at these signals in detail.

Not only were the Catalans still subjected to in their view “arbitrary” arrests legitimated by the Duke, the Genoese now joined the fray of complaints, pointing at not only the tax causing collateral damage to other trading nations in Bruges but also these Duke-sanctioned reprisals. Over the course of 1443, the Members argued that ducal officers had arrested the Catalans in direct violation of their safe-conduct. It is important to note that simultaneously the Catalans were active at the home front, petitioning their King to instigate a reprisal and sequester Flemish possessions in his lands (HLS II (1419–1467), 868, 872, 878;

Carrère 1967, p. 113). Both sides were diplomatically signalling a low point in mutual trust—the continued and even heightened taxation of Catalan trade and the threat of reprisal on Flemish trade interests by Aragon. These were credible ‘costly signals’ that pushed the trading relationship between Catalonia and Flanders to the brink. Moreover, these diplomatic signals attest to the Catalans (and the Castilians before them), as well as other traders, as not being mere passive consumers of ducal decisions. They actively contested Philip’s decisions.

Although individuals such as le Noble and Van Campen were believed to have a legitimate claim in demanding restitution from the Catalans, clearly the Members—with Bruges at the forefront—thought the coercive reprisals were going too far. The Duke was, to put it mildly, overstepping the bounds of proportionality. The measure was not proportionate to the damage incurred by several Flemish merchants, bordering on portraying the Duke and his officials as predatory. This was an awful signal to project. With the spectre of escalating rounds of reprisal hanging over their heads, Bruges started repeating Catalan claims that these measures were “unjust” (HLS II, 873). The signal, combining fiscal pressure with reprisals, punishing Catalans for their transgressions at sea and subjecting their access to the Bruges market, seemed to have overhit its target. These events and complaints, these signals, led to the Duke’s decision to finally rescind the tax in 1450. Such diplomatic signals, relating to transaction costs and an overbearing—if not predatory—ducal fiscal policy, are absent in the existing literature.

Importantly, it was a corrective measure that was forced by Philip’s wife Isabella’s (1397–1471) actions, whose personal relationship to the King of Aragon (her brother was married to Alfonso V’s sister) cannot be understated. Her own personal financial receiver, Paul (not Pieter) Van Campen, was one of the officials presiding over the committee that advised the abolition of the tax on Catalan trade on grounds that it was raising more funds than intended (

Sommé 1998, pp. 442–43).We know from the historiography that Isabella was a formidable ruler in her own right, often acting in Duke Philip’s stead if needed, including in matters of diplomacy. In fact, we know she travelled to Aragon in 1448 (

Sommé 1998, p. 443). If we combine her diplomatic pedigree and involvement of her high officers with the complaints from various merchants outlined above, it is arguable that the Duke was pressured through both formal and informal channels to annul a tax that was doing more harm than good. The signals of distress were, consequently, not just of Catalan or formal diplomatic origin.

We know the punitive tax was abolished on the 30 January 1450, preceding a period of relative recovery of Catalan trade in the period leading up to de Boer’s troublesome

fets. Between 1454 and 1463, around 30 Catalan trading missions found their way to Flanders. Compare that to sixteen between 1441 and 1453, coinciding with the tax controversy. It is not surprising then that only five Catalans remained in Bruges by 1452. Surely the impact on their transaction costs by this tax played a role. Philip’s rescinding of the tax, as mentioned above, was accompanied by a long justification of why he had initially taken the decision to raise it, including a principle of consistency; a similar tool was used to punish the Castilians for their maritime transgressions. Interestingly, however, this was only raised with the decision to rescind the tax in 1450. In that justification, the Duke cited Le Noble and Van Campen’s failed attempts to claim restitution via the Aragonese authorities, implying he had the residuary duty to intervene where the Aragonese authorities had failed to do so, first via letters of marque and reprisal and then via the punitive tax. The Duke presented himself as a caring overlord, eager to help his subjects who had suffered considerable commercial damages, an injustice that imperilled trade, thereby signalling his benevolence. What is also true is that he was helping his own interests in salvaging an expensive expedition to the Holy Land, which suffered at the hands of Catalan sea robbers (

Paviot 2003, p. 90;

Sommé 1998, p. 442).

By now, however, Philip the Good and Flanders had twice risked the wrath of merchant communities via the imposition of punitive taxes conditioning their market access and considerably changing their transaction costs. This signalled a willingness to go to the diplomatic brink, which had almost permanently lost Flanders much of its Iberian trade. These were the wrong ‘costly signals‘ to send—a brinkmanship that forced ducal decisions to rescind both taxes. This perspective has hitherto not been considered as such. Both tax controversies involved disputes that were intimately related to the behavioural contract underpinning the safe-conducts and privileges granted to the Castilians and Catalans. Finot’s analysis of the rescindment was positive, claiming it gave a new vigour to direct commercial relations between Flanders and Barcelona until the end of the fifteenth century (

Finot 1899, p. 191). It is a claim that seems difficult to reconcile with de Boer’s study of the

fets, and to which this article adds a problematisation before those

fets in the mid-fifteenth century, namely that Catalan commerce in Flanders in the first half of the fifteenth century was heavily troubled by tax and maritime violence. The events leading up to the tax, as well as the ‘arbitrary’ arrests, were quite the dent in the behavioural contract that existed between the Catalans and their Flemish hosts, whereby adding a fiscal condition to market access imperiled yet another stream of Bruges’ trade. Differing from the Castilian experience, however, was a duke who saw an opportunity to attach his own financial interests on a policy type he had attempted before for a similar situation. His involvement in the Catalan case appears much more forceful and opportunistic than it was for the Castilian case. Therefore, these observations clash with the characterisation of Duke Philip’s commercial policy as being defined by the absence of his initiative (

Desportes Bielsa 1999, p. 377). The ‘costly signal’ of adding his own financial interest to the Catalan tax is most certainly evidence of the possibility of ducal initiative in commercial affairs.