The Dynamic Pineal Gland in Text and Paratext: Florentius Schuyl and the Corporeal–Spiritual Connection of the Brain and Soul in the Latin Editions (1662, 1664) of René Descartes’ Treatise on Man

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Descartes’ Treatise on Man

I expect that you have been waiting for me to send you the treatise which I promised you... It is almost finished … but I would prefer to keep it for a few months, to revise it and rewrite it, and to draw some diagrams which are necessary. They are quite a trouble for me, for as you know I am a very poor draughtsman...

Doubtless you know that Galileo was recently censured by the Inquisitors of the Faith, and that his views about the movement of the earth were condemned as heretical. I must tell you that all the things I explained in my treatise [The World], which included the doctrine of the movement of the earth, were so interdependent that it is enough to discover that one of them is false to know that all the arguments I was using are unsound. Though I thought they were based on very certain and evident proofs, I would not wish, for anything in the world, to maintain them against the authority of the Church. … I desire to live in peace and to continue the life I have begun under the motto to live well you must live unseen. … I am more happy to be delivered from the fear of my work’s making unwanted acquaintances than I am unhappy at having lost the time and trouble which I spent on its completion

3. Descartes and the Corporeal–Spiritual Connection of the Pineal Gland and the Rational Soul

I will answer the question you asked me about the function of the little gland called conarion [i.e., the pineal gland4]. My view is that this gland is the principal seat of the soul, and the place in which all our thoughts are formed. The reason I believe this is that I cannot find any part of the brain, except this, which is not double. Since we see only one thing with two eyes, and hear only one voice with two ears, and altogether have only one thought at a time, it must necessarily be the case that the impressions which enter by the two eyes or by the two ears, and so on, unite with each other in some part of the body before being considered by the soul. Now it is impossible to find any such place, in the whole head, except this gland; moreover it is situated in the most suitable possible place for this purpose, in the middle of all the concavities [sic, The pineal gland is not located within the ventricular system]; and is supported and surrounded by the little branches of the carotid arteries which bring the spirits into the brain

I do not altogether deny that the impressions which serve memory may be partly in the gland called conarium [the pineal gland], especially in dumb animals and in people who have a coarse mind. But it seems to me that others would not have the great facility which they have in imagining an infinity of things which they have never seen, if their souls were not joined to some part of the brain capable of receiving all kinds of new impressions, and consequently not at all suitable for preserving old ones. Now there is only this gland to which the soul can be joined; for there is nothing else in the whole head which is not double. But I think that it is the other parts of the brain, especially the interior parts, which most serve memory. I think that all the nerves and muscles can serve it, too, so that a lute player, for instance, has a part of his memory in his hands: for the ease of bending and [moving] his fingers in various ways, which he has acquired by practice, helps him to remember the passages which need these dispositions when they are played

[T]he pituitary gland is akin to the pineal gland in that both are situated between the carotid arteries and on the path which the spirits take in rising from the heart to the brain. But this gives no ground to suppose that the two have the same function; for the pituitary gland is not, like the pineal gland, in the brain, but beneath it and entirely separate,5 in a concavity of the sphenoid bone specially made to take it, and even beneath the dura mater if I remember correctly. Moreover, it is entirely immobile, whereas we experience, when we imagine, that the seat of the common sense … the part of the brain in which the soul performs all its principal operations, must be mobile. It is not surprising that the pituitary gland should be situated as it is between the heart and the conarium, because there are many little arteries there, forming the carotid plexus [i.e., the mythical plexus mirabilis/rete mirabile] also, which come together there without reaching the brain. For it is a general rule throughout the body that there are glands at the meeting points of large numbers of branches of veins or arteries. It is not surprising either that the carotids send many branches to that point; that is necessary to feed the bones and other parts, and … to separate the coarser parts of the blood from the more rarefied parts which alone travel through the straightest branches of the carotids to reach the interior of the brain, where the conarium is located [sic].6

There is no need to suppose that this separation takes place in any but a purely mechanical manner. When reeds and foam are floating on a stream which splits into two branches, the reeds and foam will be seen to go into the branch in which the water flows in a less straight line. The present case is similar. There is good reason for the conarium to be like a gland, because the main function of every gland is to take in the most rarefied parts of the blood which are exhaled by the surrounding vessels, and the function of the conarium is to take in the animal spirits in the same manner. Since it is the only solid part in the whole brain which is single [unpaired], it must necessarily be the seat of the common sense, i.e., of thought [sic, not the traditional concept of common sense,7 but instead an aspect of reason], and consequently of the soul; for one cannot be separate from the other. The only alternative is to say that the soul is not joined immediately to any solid part of the body, but only to the animal spirits which are in its concavities, and which enter it and leave it continually like the water of a river. That would certainly be thought too absurd. Moreover, the conarium is so placed that it is easy to understand how the images which come from the two eyes, or the sounds which enter by the two ears, must come together at the place where it is situated. They could not do this in the concavities, except in the middle one, or in the channel just below the conarium [i.e., the aqueduct of Sylvius]; and this would not do, because these cavities are not distinct from the others in which the images are necessarily double

[I disagree with your recent objections about the conarium,] namely, that no nerve goes to the conarium and that it is too mobile to be the seat of the common sense. In fact, these two things tell entirely in my favour. Each nerve is designed for a particular sense or movement, some going to the eyes, others to the ears, arms, and so on. Consequently, if the conarium was specially connected with one in particular, it could be deduced that it was not the seat of the common sense which must be connected to all of them in the same way. The only way in which they can all be connected with it is by means of the spirits, and that is how they are connected with the conarium. It is certain too that the seat of the common sense must be very mobile, to receive all the impressions which come from the senses; but it must also be of such a kind as to be movable only by the spirits which transmit these impressions. Only the conarium fits this description

Now I will tell you that when God unites a Reasonable Soul to this machine … he will give it its principal place in the brain, and will make it of such a nature that, according to the various ways in which the entrances of the pores which are on the interior surface of this brain [i.e., the ventricular walls] will open through the intermediary of the nerves, it will have various feelings

Now among these figures [sensory impressions], it is not those which are imprinted in the organs of the external senses, or on the interior surface of the brain [i.e., the ventricular walls], but only those which are traced in spirits on the surface of the gland H [pineal gland], where the seat of the Imagination and of common sense are located; [the representation of such images on the surface of the pineal gland] must be taken for the ideas, that is to say for the forms or images which the Reasonable Soul will immediately consider, when being united to this machine it imagines or feels some object

[W]hen there is a Soul in this machine, it will sometimes be able to feel various objects through the same organs, arranged in the same way, and without anything at all changing, except the configuration of gland H

4. Descartes on the Motility of the Pineal Gland

Consider … that gland H [pineal gland] is composed of matter that is very soft, and that it is not entirely joined and united to the substance of the brain, but only attached to small arteries (whose skins are quite loose and pliable) and supported as if in balance by the force of the blood that the heat of the heart pushes towards it; so that it takes very little to determine it to incline and bend more or less, sometimes to one side, sometimes to another, and to make it so that in bending, it arranges the spirits that come out of it to take their course towards certain places of the brain, rather than towards others

Now there are two principal causes, without counting the force of the Soul, … which can make it move in this way… The first is the difference which is found between the small parts of the Spirits which come out of it: For if all these Spirits were of exactly equal force, and there were no other cause which determined it to flow here or there, they would flow equally into all its pores, and would support it completely straight and immobile in the center of the head… But like a body attached only to a few threads, which would be supported in the air by the force of the smoke which would come out of a furnace, would float incessantly here and there, according as the various parts of this smoke acted against it differently; Thus the small parts of these Spirits, which lift and support this gland, being almost always different in some way, do not fail to agitate it and make it lean sometimes to one side and sometimes to another…

Now the principal effect [is] that the Spirits thus coming out more particularly from some places on the surface of this gland, than from others, can have the force to turn the small tubes of the interior surface of the brain in which they are going, towards the places from which they come out, if they do not find them already turned there; and by this means to move the members to which these tubes relate, towards the places to which these places on the surface of the gland H [pineal gland] relate. If we have an idea about moving a member [e.g., a limb], that idea, consisting only in the way in which these Spirits then come out of this gland, is what causes the movement

[W]hen there is a Soul in this machine, it will sometimes be able to feel various objects through the intermediary of the same organs, arranged in the same way, and without there being anything at all that changes, except the situation of the gland H [pineal gland]

[W]hen the gland H [pineal gland] is inclined towards one side, by the sole force of the spirits, without the Rational Soul or the external senses contributing to it, the ideas which are formed on its surface do not only proceed from the inequalities which are found between the small part[icle]s of these Spirits, and which cause the difference of the humors…, but they also proceed from the impressions of the memory

I need no proof of the motility of this gland apart from its situation; because since it is supported only by the little arteries which surround it, it is certain that very little will suffice to move it. But for all that I do not think that it can go far one way or the other

5. Schuyl’s Illustrations of the Pineal-Soul Connection

6. Descartes’ Bête-Machine Doctrine

[I]t would not suffice that [the soul] be placed in the human body, as is a pilot in his ship, unless perhaps to move its members. Instead, it is necessary that the soul be joined and united more closely to the body, [to have] feelings and appetites similar to ours, and thus compose a true man”

After error of those who deny God … there is no other [error] which draws feeble minds away from the straight path of virtue so often than that of imagining that the soul of beasts is of the same nature as ours, and that as a result, we have nothing to fear nor to hope for after this life, any more than do flies and ants; whereas, when we know how much they differ, we have a much better understanding of the reasons which prove that our soul is of a nature entirely independent of the body, and as a result, that the soul is not subject to death along with the body. Then … we are naturally led to judge from this that it is immortal

[Fromondus] asks what is the point of attributing substantial souls to animals, and goes on to say that my views will perhaps open the way for atheists to deny the presence of a rational soul even in the human body. I am the last person to deserve this criticism, since, like the Bible, I believe, and I thought I had clearly explained, that the souls of animals are nothing but their blood, the blood of which is turned into [animal] spirits by the warmth of the heart and travels through the arteries of the brain and from it to the nerves and muscles. This theory involves such an enormous difference between the souls of animals and our own that it provides a better argument than any yet thought of to refute the atheists and establish that human minds cannot be drawn out of the potentiality of matter. And on the other side, I do not see how those who credit animals with some sort of substantial soul distinct from blood, heat, and [animal] spirits, can answer such Scripture texts as Leviticus 17:14 (“The soul of all flesh is in its blood, and you shall not eat the blood of any flesh, because the soul of flesh is in its blood”) and Deuteronomy 12:23 (“Only take care not to eat their blood, for their blood is their soul, and you must not eat their soul with their flesh”). Such texts seem much clearer than others which are quoted against certain opinions which have been condemned solely because they appear to contradict the Bible. Moreover, since these people posit so little difference between the operations of a man and of an animal, I do not see how they can convince themselves [that] there is such a great difference between the natures of the rational and sensitive souls

[I]f we wish by reasoning to determine whether any of the motions of brutes are similar to those which we accomplish with the aid of the mind, or whether they resemble those that depend alone upon the influxus of the animal spirits and the disposition of the organs, we must pay heed to the differences that prevail between the two classes… [A]ll the actions of brutes resemble only those of ours that occur without the aid of the mind. Whence we are driven to conclude that we can recognize no principle of motion in them beyond the disposition of their organs and the continual discharge of animal spirits that are produced by the beat of the heart as it rarefies the blood. At the same time we shall perceive that we have had no cause for ascribing anything more to them, beyond that, not distinguishing these two principles of motion, when previously we have noted that the principle depending solely on the animal spirits and organs exists in ourselves and in the brutes alike, we have inadvisedly believed that the other principle, that consisting wholly of mind and thought, also existed in them. And it is true that a persuasion held from our earliest years, though afterwards shown by argument to be false, is not easily and only by long and frequent attention to these arguments expelled from our belief

I would not want to say that movement was the soul of beasts, but rather, according to holy Scripture and Deuteronomy 12:23, that blood is their soul. For blood is a fluid body, which is very lively, and its more rarefied part[icle]s are called spirits. It is these, flowing from the arteries through the brain into the nerves and muscles, which move the whole machine of the body

[T]here is no prejudice to which we are all more accustomed from our earliest years than the belief that dumb animals think. Our only reason for this belief is the fact that we see that many of the organs of animals are not very different from ours in shape and movement. Since we believe that there is a single principle within us which causes these motions—namely the soul, which both moves the body and thinks—we do not doubt that some such soul is to be found in animals also. I came to realize, however, that there are two different principles causing our motions; one is purely mechanical and corporeal and depends solely on the force of the spirits and the construction of our organs, and can be called the corporeal soul; the other is the incorporeal mind, the soul which I have defined as a thinking substance. Thereupon I investigated more carefully whether the motions of animals originated from both these principles or from one only. I soon saw clearly that they could all originate from the corporeal and mechanical principle, and I thenceforward regarded it as certain and established that we cannot at all prove the presence of a thinking soul in animals. I am not disturbed by the astuteness and cunning of dogs and foxes, or all the things which animals do for the sake of food, sex, and fear; I claim that I can clearly explain the origin of all of them from the constitution of their organs

But though I regard it as established that we cannot prove there is any thought in animals, I do not think it is thereby proved that there is not, since the human mind does not reach into their hearts. But when I investigate what is most probable in this matter, I see no argument for animals having thoughts except the fact that since they have eyes, ears, tongues, and other sense-organs like ours, it seems likely that they have sensation like us; and since thought is included in our mode of sensation, similar thought seems to be attributable to them. … But there are other arguments, stronger and more numerous, but not so obvious to everyone, which strongly urge the opposite. One is that it is more probable that worms and flies and caterpillars move mechanically than that they all have immortal souls

[I]n my opinion the main reason which suggests that the beasts lack thought is the following. … [A]lthough all animals easily communicate to us, by voice or bodily movement, their natural impulses of anger, fear, hunger and so on, it has never been observed that any brute animal reached the stage of using real speech, … of indicating by word or sign something pertaining to pure thought and not to natural impulse. Such speech is the only certain sign of thought hidden in the body. All men use it, however stupid and insane they may be, and though they may lack tongue and organs of voice; but no animals do. Consequently, it can be taken as a real specific difference between men and dumb animals

7. Schuyl’s Textual/Figural Inconsistencies Concerning the Bête-Machine Doctrine

[Descartes] wanted to destroy that most terrible opinion, which, by a kind of wicked metamorphosis and metempsychosis,16 strives to change men into beasts and beasts into men, desecrating by excessive affinity with brutes the incorporeal and incorruptible mind by which man is called by special prerogative the image of God.(Schuyl’s Ad Lectorem in Des Cartes 1662, although the preface is not paginated, this quotation is from the 4th page of the preface; see also Vermij 2024, p. 201).

8. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Primus inaccessum qui per tot sæcula verum Eruit è tetris longæ caliginis umbris, Mysta sagax, Natura, tuus, sic cernitur Orbi Cartesius. Voluit sacros in imagine vultus Fungere victuræ artificis pia dextera famæ, Omnia ut aspicerent quem sæ nulla tacebunt. He was the first to extract the truth, inaccessible for so many centuries, out of the dark shadows of the long fog; Nature, your wise sage, Cartesius, appears thus to the world. The dutiful right hand of the artist wanted to join the sacred face on the painting to everlasting fame, so that all generations might look upon the one whom no generations will be silent over. (Translation from Latin modified from Hynes 2010) |

| 2 | Schuyl earned a Master of Philosophy degree from the University of Utrecht in 1639 and then enrolled at the University of Leiden to continue his philosophical studies. However, in 1640 he accepted a position as professor of philosophy at the Gymnasium Illustre in ’s-Hertogenbosch. He came to some prominence after publishing the Latin edition of Descartes Treatise on Man in 1662 with a second edition in 1664. In 1664 he also earned his doctorate in medicine in Leiden and was very soon thereafter appointed as professor of medicine at Leiden University. In 1667 he was appointed professor of botany and head of the Hortus Botanicus in Leiden. He died of plague in 1669. |

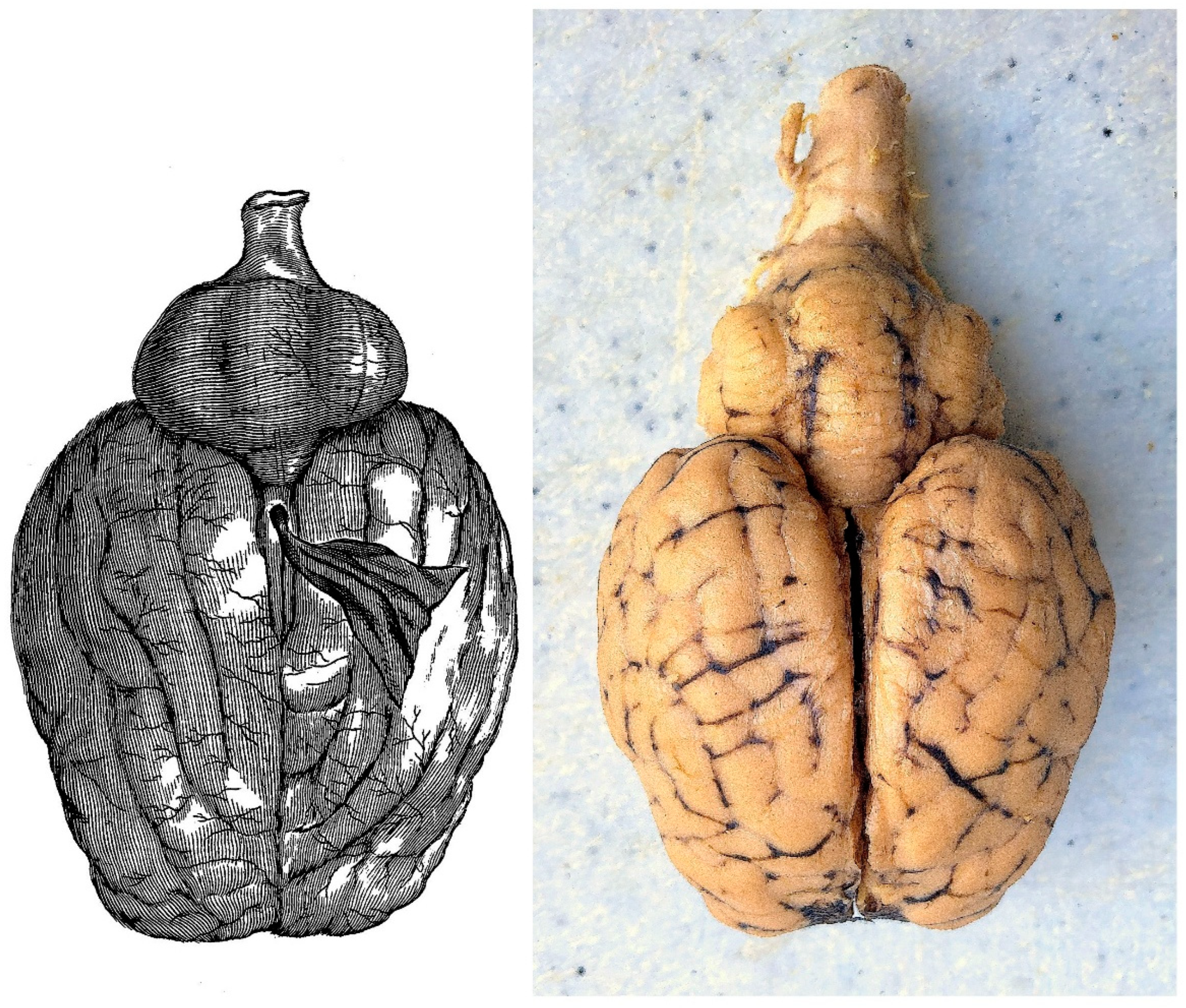

| 3 | All the illustrations in this paper were derived by the author from high-quality scans from the original 17th-century sources, or from photographs taken by the author of a sheep brain dissection for comparison with relevant historical images. The various illustrations were digitally edited to obtain high-resolution, high-contrast, black-and-white illustrations that minimized blemishes, noise, and distortions. |

| 4 | Ancient Greeks were the first to notice the pineal gland and some believed it to be a valve-like structure, a guardian for the flow of pneuma (vital spirits). Galen in the 2nd century C.E. in the eighth book of his De usu partium (On the use of the parts) gave it the name “κωναριον” (konárion), meaning “little pinecone”, which during the Renaissance was translated to Latin as pinealis (Galen and May 1968, p. 418). Galen himself denied that the pineal gland was part of the encephalon, considered it to be a gland based on its appearance and texture, noted that it did not project into the third ventricle but was instead attached “to the outside of the ventricle”, argued strongly against the idea that it functioned as a valve-like structure, and in Galen’s typical hubristic and arrogant fashion labeled those who believed that the pineal gland “regulated the pneuma” (as Descartes would later claim) as “ignorant” (Galen and May 1968, p. 419). While Galen was an advocate of the Platonic theory of the tripartite soul, he did not in any manner link the function of the pineal gland to the rational soul as Descartes later did (Shiefsky 2012). In the 17th century, Descartes made the pineal gland the foundation for Cartesian physiology, which like Descartes’ word choice (variously spelled “conarion” or "conarium"), reflects Descartes’ reliance on many aspects of Galenic doctrine and some Galenic physiological concepts, although Descartes ignored or misinterpreted what Galen wrote about the location, mobility, and function of the pineal gland (Galen and May 1968). Indeed, Galen’s views were far closer to a modern understanding of these aspects of the pineal gland that were Descartes’ views more than 1500 years later. |

| 5 | This was almost a century after publication of Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica (Vesalius 1543), in which Vesalius had argued forcefully and correctly that this plexus does not exist in humans (Lanska 2015, 2022b). |

| 6 | The blood supply to the pineal gland is not from the anterior (carotid circulation) but primarily from the choroidal branches of the posterior cerebral artery. Unlike most of the mammalian brain, the pineal gland is not isolated from the body by the blood–brain barrier system. |

| 7 | The common sense (often referred to as sensus communis or communis sensus) was then generally considered a mental faculty that unified the sensory perceptions from the various sensory modalities (e.g., vision, audition, gustation) into a single, unified perception of the external world (Lanska 2022a). |

| 8 | As Galen wrote in the eighth book of De usu partium (On the use of the parts), anticipating (and in effect denigrating) the 17th-century views of Descartes, “But perhaps someone will say, ‘What is to prevent [the pineal gland] from having a motion of its own?’ What, indeed, other than that if it had, the gland on account of its faculty and worth would have been assigned to us as an encephalon, and the encephalon itself would be only a body divided by many canals and would be like an instrument that was suited to be of service to a part formed by Nature to move and capable of doing so? Why need I mention how ignorant and stupid these opinions are?” (Galen and May 1968, pp. 419–20). |

| 9 | Initially the smoke from a chimney rises in a smooth upward pattern (i.e., laminar flow), but it soon becomes turbulent and unpredictable (i.e., chaotic flow) in a way that is extremely sensitive to small differences in initial conditions. |

| 10 | In Hebrew, ruach (רוּחַ) encompasses the concepts of spirit, breath (or breath of life), and wind (or movement of air), often referring to the divine presence or influence of God (divine breath or breath of God) in religious contexts (see, for example, Genesis 2: 7, Ezekiel 37: 5–6, and Job 34: 14–15). Schuyl’s visual image of a billowing fabric or blowing curtain to represent the corporeal-spiritual connection in man seems to have been chosen to illustrate this Judeo-Christian framework, a framework that also likely influenced Descartes’ and Schuyl’s belief that humans, but no other creatures, are capable of spoken logos (rational discourse). |

| 11 | The flap anatomy of an illustration of the heart in De Homine (Des Cartes 1662; Descartes 1664a) is more often recognized as such and much better known (Crummer 1932). One factor in the lack of recognition of the pineal gland illustration as a flap anatomy may relate to the fragility of the small movable part in the pineal gland illustration. Although no survey of extant first- or second-edition copies of De Homine has been attempted, the very small movable portion of the pineal gland illustration may be missing in many of them. |

| 12 | In the early 1630’s, Gutschoven was a pupil and assistant of Descartes in the Dutch Republic. In 1635, he returned to his hometown of Leuven, where he became professor of mathematics in 1646. In 1652, after the death of his wife, Gutschoven entered the monastery, and in 1659 he became professor of anatomy, surgery, and botany. |

| 13 | La Forge contributed illustrations and a commentary to the 1664 edition of Descartes’s Traité de l’homme; and in 1666 he published his own account of the human mind and its relation to the body following Cartesian principles, the Traité de l’esprit de l’homme (La Forge 1666). |

| 14 | The Principality of Liège was a Roman Catholic ecclesiastic state of the Holy Roman Empire, located mostly in present-day Belgium. |

| 15 | Past Dean and University Professor of Biology and History of Science at Washington University, St. Louis. |

| 16 | Metempsychosis is the supposed transmigration at death of the soul (of a human being or animal) into a new body of the same or a different species. |

| 17 | It was only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the posterior pituitary (the neurohypophysis) was recognized as a neuro-endocrine structure comprised largely of axonal projections from the hypothalamus. |

| 18 | Almost half of the canonical edition of Descartes’ collective works is devoted to correspondence (Descartes 1970, p. vii). |

References

- Andrault, Raphaële. 2016. Anatomy, mechanism and anthropology: Nicholas Steno’s reading of L’Homme. In Descartes’ Treatise on Man and Its Reception. Edited by Antoine-Mahut Delphine and Stephen Gaukroger. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, vol. 43, pp. 175–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Eleanor. 2016. Beautiful surfaces. Style and substance in Florentius Schuyl’s illustrations for Descartes’ Treatise on Man. Nuncius 31: 251–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Desmond M. 2003. Descartes’ Theory of Mind. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Lucinda, and Robert Markley. 2014. Human, animal, and machine in the seventeenth century. In A Companion to British Literature: Volume II: Early Modern Literature 1450–1660. Edited by Robert De Maria, Jr., Heesok Chang and Samantha Zacher. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 375–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cottingham, John, ed. 1992. The Cambridge Companion to Descartes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crummer, LeRoy. 1932. A check list of anatomical books illustrated with cuts with superimposed flaps. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 20: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Des Cartes, Renatus [Descartes, René]. 1641. Renati Des-Cartes, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia, in qva dei Existentia, & Animæ Immortalitas Demonstratur. Parisiis: Michaelem Soli. [Google Scholar]

- Des Cartes, Renatus [Descartes, René]. 1662. De Homine Figuris et Latinitate Donatus a Florentioi Schuyl. Lugduni Batavorum [Leyden]: Petrum Leffen et Franciscus Moyardum. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1637. Discours de la Methode: Pour Bien Conduire sa Raison, & Chercher la Verité Dans les Sciences. Plus: La Dioptriqve. Les Meteores. Et La Geometrie. Qui Sont des Essais de Cete Methode. Leyde: Ian Maire. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1659a. Geometria, à Renato Des Cartes: Anno 1637 Gallicè Edita; Postea Autem: Unà Cum Notis: Florimondi de Beavne, In Curia Blesensi Consiliarii Regii, Gallicè Conscriptis in Latinam Linguam Versa, & Commentariis Illustrata, Operâ Atque Studio: Francisci à Schooten, in Acad. Lugd. Batava Mathefeos Professoris. Nunc Demum ab Eodem Diligenter Recognita, Locupletioribus Commentariis Instructa, Multisque Egregiis Accessionibus, tam ad Uberiorem Explicationem, Quàm ad Ampliandam Bujus Geometria Excellentiam Facientibus, Exornata, Quorum Omnium Catalogum Pagina Verfa Exhibet. Amsterdami: Ludovicum & Danielem Elzevirios. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1659b. Lettres de Mr Descartes, où Sont Traittées les Plus Belles Questions de la Morale, de la Physique, de la Médecine et des Mathématiques. Tome 2. Edited by Claude Clerselier. Paris: Charles Angot. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1664a. Renatus Des Cartes de Homine Figuris Et Latinitate Donatus a Florentio Schuyl, Inclytæ Urbis Sylvæ-Ducis, Senatore, & ibidem Philosophiæ Professore. Lvgdvni Batavorvm [Leiden]: Ex officinâ Hackiana. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1664b. L’Homme de René Descartes et un Traitté de la Formation du Foetus du Mesme Autheur. Avec les Remarques de Louys de La Forge … Sur le Traitté de l’Homme de René Descartes; & sur les Figures pur luy Inventées. Paris: Charles Angot. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1897. Oeuvres de Descartes: Correspondance I: Avril 1622-Février 1638. Publiées par Charles Adam & Paul Tannery Sous les Auspices du Ministère e L’instruction Publique. Paris: Léopold Cerf, Imprimeur-Éditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1899. Oeuvres de Descartes: Correspondance III: Janvier 1640-Juin 1643. Publiées par Charles Adam & Paul Tannery Sous les Auspices du Ministère e L’instruction Publique. Paris: Léopold Cerf, Imprimeur-Éditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1901. Oeuvres de Descartes: Correspondance IV: Juillet 1643 0 Avril 1647. Publiées par Charles Adam & Paul Tannery Sous les Auspices du Ministère e L’instruction Publique. Paris: Léopold Cerf, Imprimeur-Éditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1936. Correspondance: Publiée Avec une Introduction et des Notes par Ch[arles] Adam et G[érard] Milhaud. Tome I. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1939. Correspondance: Publiée avec une Introduction et des Notes par Ch[arles] Adam et G[érard] Milhaud. Tome II. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1947. Correspondance: Publiée avec une Introduction et des Notes par Ch[arles] Adam et G[érard] Milhaud. Tome IV. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1951. Correspondance: Publiée avec une Introduction et des Notes par Ch[arles] Adam et G[érard] Milhaud. Tome V. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1955. The Philosophical Works of Descartes. Translated by Elizabeth Sanderson Haldane, and George Robert Thomson Ross. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 1970. Descartes’ Philosophical Letters. Edited and Translated by Anthony Kenny. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 2001. Discourse on Method, Optics, Geometry, and Meteorology, rev. ed. Translated, with an introduction by Paul J. Olscamp. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 2003. Treatise of Man. Translation and Commentary by Thomas Steele Hall. Amherst and New York: Prometheus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, René. 2004. The World and Other Writings. Edited and Translated by Stephen Gaukroger. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galen, and Margaret Tallmadge May. 1968. Galen: On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body: Περὶ χρείας μορίων; De usu Partium. Translated from the Greek with an introduction and commentary by Mary Tallmage May. Cornell Publications in Science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaukroger, Stephen. 1995. Descartes: An Intellectual Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaukroger, Stephen, John Schuster, and John Sutton, eds. 2000. Descartes’ Natural Philosophy. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1987. Seuils. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (Literature, Culture, Theory). Translated by Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, Darren. 2010. Parallel traditions in the image of Descartes: Iconography, intention, and interpretation. The International History Review 32: 575–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Forge, Louis de. 1666. Traitté de l’esprit de l’homme, de ses Facultez et Fonctions, et de son Vnion Auec le Corps. Suiuant les Principes de Rene’ Descartes. Paris: Michel Bobin and Nicolas Le Gras. [Google Scholar]

- Lanska, Douglas J. 2015. The evolution of Vesalius’s perspective on Galen’s anatomy. Istoriya Meditsiny (History of Medicine) 2: 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanska, Douglas J. 2022a. Evolution of the myth of the human rete mirabile traced through text and illustrations in printed books: The case of Vesalius and his plagiarists. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 31: 221–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanska, Douglas J. 2022b. The medieval cell doctrine: Foundations, development, evolution, and graphic representations in printed books from 1490 to 1630. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 31: 115–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanska, Douglas J. 2024a. Illustrations of the pineal gland in Descartes’ oeuvre. Child’s Nervous System 41: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanska, Douglas J. 2024b. The medieval cell doctrine. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Edited by S. Murray Sherman. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanska, Douglas J. 2025. Book review: The Good Cartesian: Louis de La Forge and the Rise of a Philosophical Paradigm [by Steven Nadler]. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Gerald J., and Deborah A. Boyle. 1999. Descartes’s tests for (animal) mind. Philosophical Topics 27: 87–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Steineg, Theodor. 1911. Studien zur Physiologie des Galenos. Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin 5: 172–224. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Katherine. 2000. Bêtes-machines. In Descartes’ Natural Philosophy. Edited by Gaukroger Stephen, John Schuster and John Sutton. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 401–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler, Steven. 2016. The art of Cartesionism: The illustrations of Clerselier’s edition of Descartes’s Traité de l’homme (1664). In Descartes’ Treatise on Man and Its Reception. Edited by Antoine-Mahut Delphine and Stephen Gaukroger. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, vol. 43, pp. 193–223. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler, Steven. 2024. The Good Cartesian: Louis de la Forge and the Rise of a Philosophical Paradigm. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Lex. 2001. Unmasking Descartes’s case for the bête machine doctrine. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 31: 389–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, Lawrence. 2016. Descartes’ life and works. In The Cambridge Descartes Lexicon. Edited by Nolan Lawrence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. xxxxv–lxvi. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Woosuk. 2012. On animal cognition: Before and after the beast-machine controversy. In Philosophy and Cognitive Science. Studies in Applied Philosophy, Epistemology and Rational Ethics. Edited by Magnani Lorenzo and Ping Li. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 2, pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Woosuk. 2017. On animal cognition: Before and after the beast-machine controversy. In Abduction in context. Studies in Applied Philosophy, Epistemology and Rational Ethics. Edited by Park Woosuk. Cham: Springer, vol. 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, Leonora Cohan. 1968. From Beast-Machine to Man-Machine. Animal Soul in French Letters from Descartes to La Mettrie, 2nd ed. New York: Octagon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shiefsky, Mark. 2012. Galen and the tripartite soul. In Plato and the Divided Self. Edited by R. Barney, T. Brennan and C. Brittain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 331–49. [Google Scholar]

- Steno, Nicolaus. 1965. Nicolaus Steno’s Lecture on the Anatomy of the Brain. Copenhagen: Arnold Busck. [Google Scholar]

- Steno, Nicolaus. 2013. The discourse on the anatomy of the brain. In Nicolaus Steno: Biography and Original Papers of a 17th Century Scientist. Edited and Translated by Troels Kardel, and Paul Maquet. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 603–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stenon, Nicolas. 1669. Discovrs de Monsievr Stenon, svr L’anatomie dv Cerveav. A Messievrs de L’assemblée, qui se Fait chez Monsieur Theuenot [Thévenot]. Paris: Robert de Ninville. [Google Scholar]

- Tweed, Hanna C., and Diane G. Scott, eds. 2018. Medical Paratexts from Medieval to Modern: Dissecting the Page. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Vermij, Rienk. 2024. Florentius Schuyl and the origin of the beast-machine controversy. History of European Ideas 50: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesalius, Andreas. 1543. Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, scholae medicorum Patauinae professoris, de Humani corporis fabrica Libri septem. Basileæ [Basel], Ioannis Oporini [Johannes Oporinus]. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin, Rebecca M. 2003. Figuring the dead Descartes: Claude Clerselier’s Homme de René Descartes (1664). Representations 83: 38–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lanska, D.J. The Dynamic Pineal Gland in Text and Paratext: Florentius Schuyl and the Corporeal–Spiritual Connection of the Brain and Soul in the Latin Editions (1662, 1664) of René Descartes’ Treatise on Man. Histories 2025, 5, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5020024

Lanska DJ. The Dynamic Pineal Gland in Text and Paratext: Florentius Schuyl and the Corporeal–Spiritual Connection of the Brain and Soul in the Latin Editions (1662, 1664) of René Descartes’ Treatise on Man. Histories. 2025; 5(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanska, Douglas J. 2025. "The Dynamic Pineal Gland in Text and Paratext: Florentius Schuyl and the Corporeal–Spiritual Connection of the Brain and Soul in the Latin Editions (1662, 1664) of René Descartes’ Treatise on Man" Histories 5, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5020024

APA StyleLanska, D. J. (2025). The Dynamic Pineal Gland in Text and Paratext: Florentius Schuyl and the Corporeal–Spiritual Connection of the Brain and Soul in the Latin Editions (1662, 1664) of René Descartes’ Treatise on Man. Histories, 5(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5020024