1. Introduction

“I’ve labored hard all my days and fared hard. I have been greatly abused, have been obliged to do more than my part in the war; been loaded with class rates, town rates, province rates, Continental rates, and all rates...been pulled and hauled by sheriffs, constables and collectors, and had my cattle sold for less than they were worth. I have been obliged to pay and nobody will pay me. I have lost a great deal by this man and that man and t’other man, and the great men are going to get all we have, and I think it is time for us to rise and put a stop to it, and have no more courts, nor sheriffs, nor collectors, nor lawyers, and I know that we are the biggest party, let them say what they will...We’ve come to relieve the distresses of the people. There will be no court until they have redress of their grievances.”—Jedediah Peck (“Plough Jogger”) c. 1785

Here, I argue that Shays’s Rebellion was the result of the absence of party competition. The absence of political parties also meant the absence of the political institutions that accompany political parties: the ability to coordinate political activity, the ability to compile a unified list of candidates, the ability to disseminate information, and the ability to mobilize a unified voting bloc. Despite the absence of political parties, the most commercial–cosmopolitan communities are able to use the natural advantages of elites to organize in a quasi-party fashion.

To examine these dynamics, I employ a mixed-method approach, combining qualitative historical analysis with quantitative data on town-level socio-economic indicators. These variables—such as control of executive and judicial offices, newspaper ownership, and religious or social organization leadership—offer a framework to understand how commercial–cosmopolitan communities consolidated power while others were excluded. By analyzing these factors statistically, I illuminate the structural disadvantages that ultimately precipitated violent insurrection.

The analysis begins by identifying the four key advantages of commercial–cosmopolitan towns: political office control, legislative representation, information dissemination, and social organization. These advantages allowed elites to act in a quasi-party fashion, further entrenching inequality. In contrast, the least commercial–cosmopolitan towns lacked the resources and institutions necessary to mount an organized political response.

The findings suggest that these disparities, rather than simple economic distress, created a political vacuum that fostered populist frustration. This paper seeks to answer a central question: What socio-economic factors led to common political interests, and why were these interests unable to find institutional representation? By situating Shays’s Rebellion in this context, I aim to provide a deeper understanding of the political organization—or lack thereof—in early New England.

1 2. Two Coalitions of Interests

There were no political parties in the first full decade of the Commonwealth. Nonetheless, interest groups existed, and they used their political power to attain economic and political goals and defend their judicial, political, and economic institutions. The organization of such political efforts was the driving force behind the arrangement of preparty politics in Massachusetts. The ability of particular interest groups to organize effectively and influence politics was grounded in their access to resources. A careful analysis of the social and economic characteristics of 1780s Massachusetts is required in order to understand the political behavior of the era.

To grapple with the competing interests, a typology—replicated and adapted from

Hall (

1972)—is laid out: the commercial activity of Massachusetts’ 343 towns is measured using an index of commercialization, with Boston at one end and rural towns in the Berkshires and Maine at the other end (

Condon 2015;

Hall 1972).

2 Four variables are used to construct the gradient: stock in trade, silver, money lent at interest, and average vessel tonnage. Towns are ranked along these four variables. The rankings in each of the four categories are used to calculate a commercial index number for each town, generating a gradient of commercial activity.

Appendix B contains a breakdown of these variables.

3Each town’s social institutions are measured using a nine-point scale. Each town is evaluated for the presence or absence of the following: newspapers, court sessions, barristers present in 1786 or 1791, two or more barristers present in either 1786 or 1791, one or more barrister present in 1786 or 1791, the presence of a clergyman in the town for two of three years (1780, 1786, or 1791), representatives in the lower house of the General Court for at least nine of the twelve years from 1780 to 1792, and representatives in the lower house for at least six of the same twelve years. Based on the total number of points, towns are placed into one of nine groups.

Appendix C contains a breakdown of these nine groups.

The commercial index and social scale are combined into a single gradient that reflects each town’s commercial–cosmopolitan character. Each town is assigned one to ten points based on its commercial decile and from one to eight depending on the number of social variables present. These points are summed and then divided into three groups. Towns with more than twelve points fall into group A; towns with nine through twelve points fall into group B; and towns with fewer than nine points fall into group C.

Appendix D contains a breakdown of the commercial–cosmopolitan gradient.

The 54 group A towns were the sites of the most significant commercial activity and were home to nearly all social and cultural institutions, as well as the institutions of state government (

Table 1). Group B contains 88 towns with moderate commercial activity and has some connections with important social and cultural institutions. Group C contains 201 towns that were the least commercial–cosmopolitan and had little connection to any significant social or cultural institutions. In placing the towns on a commercial–cosmopolitan gradient (

Table 2), one is better able to see the division among the towns. Furthermore, this allows for the political activity of each group to be associated with its social and economic characteristics.

Across the three groups of towns, interest groups sought to influence politics. The most commercial–cosmopolitan category is found in the 54 group A towns. Individuals in the group A towns worked as commercial businessmen, bankers, investors, lawyers, clergymen, shipowners, coastal and global traders, manufacturers, and commercial fishermen. Group A residents were most concerned with advancing their own economic interests and sought to uphold the 1780 constitution and its accompanying judicial, administrative, and political institutions.

4 Artisan craftsmen, merchant sailors, and small manufacturers comprised a moderately commercial–cosmopolitan category that were also found in group A towns. Commercial farmers fall into a third category with the most significant presence in the 88 group B towns. The political interests of this third category tend toward those of the group A towns; commercial farmers in the group B towns voted and thought along the same lines as the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests because they benefited from being in sync with the interests of group A, who held the reins of power. On the other extreme of the gradient are the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests, largely composed of subsistence farmers in the 201 group C towns.

Ultimately, the four general categories of interests and the three towns boil down to two coalitions of interests, particularly in terms of polarization. On the one hand, there are the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests, motivated by the pursuit of commercial expansion, financial success, and upholding the 1780 constitution. The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests organize diligently in order to preserve their advantages. The political interests of the second and third categories very often align with the interests of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. Through placeholders that may have formally represented or lived in group B or group C towns but acted in line with the interests of the most commercial–cosmopolitan, group A held significant political clout.

On the other hand, the least commercial–cosmopolitan towns tended to be located in rural Massachusetts, western Massachusetts, and the inland areas of Maine. Residents of the least commercial–cosmopolitan towns focused on subsistence farming with little eye on profit-driven enterprise. These farmers participated in a bartering economy and tended to be uneducated. Those living in such communities who were not farmers were the merchants and artisans who subsisted in the rural, agrarian economy, providing services and goods to the inhabitants of the group C communities. Group C towns possessed a dearth of social and professional institutions, resources, and the means for political organization.

As I will show in the following pages, the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests were able to use their advantages in terms of social cohesion, resources, information sharing, and representation to ensure the levers of policymaking and governance were in their favor. At the same time, I will show how the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests, lacking such advantages, were unable to mount an effective political response.

2.1. Politics by Other Means

Each group of towns contained roughly one-third of the total population and roughly one-third of the polls (

Table 3).

5 In principle, the political power of each group should be roughly equal. However, despite the roughly equal distribution of population and polls across the towns, the group A towns were disproportionately well represented in policymaking and governance. The disproportionate presence of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests is the result of four advantages possessed by the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests.

2.2. The Power Brokers

The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests monopolize the major executive, legislative, and judicial offices in Massachusetts during the 1780s. Such a monopoly on power gives the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests an advantage in setting the policy agenda and using the institutions of the state to pursue their interests at the expense of the least commercial–cosmopolitan communities.

At the apex of the executive branch are the governor and lieutenant governor. The Massachusetts constitution of 1780 provided for the annual election of the governor and lieutenant governor (

Condon 2015;

Hough 1872;

Pole 1957). The governor holds veto power, and both offices were elected by direct popular vote, with the lieutenant governor sitting on the Governor’s Council. Furthermore, more than half of the nine seats on the Governor’s Council are held by residents of group A towns from 1780 to 1791. During these same eleven years, the governorship and lieutenant governorship passed between John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Thomas Cushing, Benjamin Lincoln, and Samuel Adams during the same years. All of these men had longstanding social and professional ties, all graduated from Harvard College, and all had homes near each other in Boston. Additionally, all of these men are important political leaders in the years prior to Independence.

6 With the governorship, the lieutenant governorship, and the Governor’s Council, controlled by residents from group A towns, the executive branch of government was a bulwark against the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests.

Qualifications for holding the governorship and lieutenant governorship gave further advantage to the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. To qualify for the governorship, a resident needed to possess a minimum property value of £1000 (

Hough 1872).

7 The high qualifications for holding such offices posed an insurmountable barrier for any polls other than the most affluent in group A towns (

Table 4).

The justices of the state supreme court were cut from the same cloth. The supreme court was composed of four men who rode circuit throughout Massachusetts and Maine. During the eleven years from 1780 to 1791, the eight men who served as justices were all from group A towns. Moreover, all but one justice graduated from Harvard College.

8 All eight justices had significant ties to commercial activity. Justices Cushing, Sargeant, Paine, and Sewall all appeared in the record of interest payments in 1786 and 1787, indicating their significant involvement in speculative or investment activity.

9 Additionally, during this era, it was customary for supreme court justices to deliver addresses before grand juries throughout the commonwealth. These addresses often veered far from legal matters and were opportunities for the justices to soliloquize, advocating their own political views to local audiences throughout the commonwealth (

Cushing 1965).

In addition to the justices of the supreme court, the judiciary’s rank and file, as well as administrative officers, were often occupied by placeholders. In this context, placeholders were leading local politicians, lawyers, officers, judges of the Court of Common Pleas and justices of the peace who lived throughout the commonwealth (

Table 5). Many of these placeholder positions were appointed by the governor without the democratic safeguards provided by civil service rules and popular elections.

Such appointed positions came with cash income, something that was rare throughout the hinterlands of Massachusetts. Desperate to hold onto their posts and their income, many of these placeholders supported the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. Others, particularly the more important positions like those on the Governor’s Council and those selected for national office, came largely from group A towns and had close social and commercial ties with commercial entrepreneurs and learned professionals in group A towns. Ultimately, inhabitants of group A towns held more than half of the terms as judges in the Court of Common Pleas (

Table 6). Judges used their position to engage in lending and other commercial activity, using their influence as judges to secure favorable terms.

Justices of the peace also exercised significant influence in local matters. Justices of the peace sat at the county level, in general sessions of the peace. The justices of the peace handed down decisions in criminal and civil cases, as well as acted as policymakers. Justices of the peace approved local infrastructure plans, issued business licenses, and set local tax rates. Justices also served as mediators for disputes among residents. Justices of the peace received fees for providing judicial and government services. Such fees were often determined by the volume of cases and matters taken up, thus giving incentive to add layers of bureaucracy and try any number of minor criminal or civil cases.

In the eleven years from 1780 to 1791, more than half of the justices of the peace were from group A towns. However, those justices who lived in the group B and C towns were placeholders and often served in the General Court. Those justices of the peace and judges of common pleas, who also served in the Senate and the house of representatives, supported the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests in exchange for the support of the judiciary and the judicial fee system that enriched the justices and judges.

Congregational ministers also served as placeholders for the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. Ministers were visible and trusted members of society and thus played an important public role in early Massachusetts. The Congregational Church was the de facto establishment church and had strong ties to the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. The upper ranks of the church hierarchy and the Congregational seminaries were anchored in the group A towns. Many Congregational ministers were educated, preached, and worked in the group A towns. Congregational ministers who were dispatched to the peripheries of the commonwealth answered to the senior clergymen located in the group A towns. As a consequence, the interests of the Congregational Church and the interests of the most commercial–cosmopolitan overlapped. The shared interests of the Congregational Church and the most commercial-commercial communities began nearly a century earlier.

Beginning in 1692, the General Court determined the geographic jurisdiction of particular Congregational Churches and set the boundaries for parishes. The General Court also imposed statewide parish taxes, levied on the residents of each parish (

Cushing 1969). The church taxes, levied by the state, were the primary source of revenue for the Congregational Church. Moreover, the General Court passed legislation that endowed each parish with the same powers of a municipal corporation, but limited to the scope of administering a system of worship (

Cushing 1969). As a result, Congregational ministers wielded significant political influence in local politics (

Table 7).

Prior to the constitution of 1780, religious organizations established outside of the formal system of municipal, Congregational parishes were not endowed with the same authority nor benefited from levied taxes. Non-Congregational denominations were widely considered subversive organizations during the colonial era and early Republic. All residents falling within a particular parish were required to pay taxes to support their respective Congregational parish, regardless of whether they regularly attended the Congregational Church or attended services for an unrecognized denomination. However, the 1780 constitution disestablished the Congregational Church. The formal disestablishment of the Congregational Church led to an increase in petitions to the General Court for the recognition of previously unrecognized denominations.

Successful petitions to the General Court for recognition afforded a newly recognized denomination the same corporate powers and tax support as a Congregational parish. After 1780, when parishioners within an existing Congregational parish splintered off, those parishioners’ levied taxes were reallocated to their newly recognized denomination. The proliferation of newly recognized denominations threatened to reduce tax revenue and local political influence for the Congregational Church. In order to stymie the proliferation of new denominations, the Congregational ministers were compelled to support the programs and policies of the most commercial–cosmopolitan class, who also had a monopoly over the executive, judiciary, and much of the General Court. In a quid pro quo, the Congregational ministers pushed the agenda of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests in their preaching and ministerial work in exchange for support of the Congregational Church in the General Court, the executive, and the judiciary. While some new denominations did emerge after the ratification of the 1780 constitution, the General Court was reluctant to recognize new religious denominations, thus preserving the Congregational Church’s revenue and political power.

However, on the other hand, the presence of new, non-Congregational denominations in the group A towns also contributed to the polarization between group A and C towns. As a result of the presence of new and non-Congregational denominations, there was greater religious diversity, primarily in group A communities. In the 1780s, 100% of group A towns had at least one minister, and 57% of those same towns had only Congregational ministers, as seen in

Table 8. Forty-three percent of group A towns had ministers from denominations other than Congregational. However, on the other extreme of the gradient, only 69% of group C towns had at least one minister, 52% of those same towns had only a Congregational minister, and a mere 10% of towns had ministers of a denomination other than Congregational.

The presence and diversity of ministers in group A towns exposed the residents to various organized religions and made residents more tolerant of religious ideas other than their own, thus making group A residents more cosmopolitan. However, group C towns, a third of which had no minister and only a tenth of which had any religious diversity, highlighted the absence of different ideas and the social isolation of the group C towns. The lack of religious diversity in the group C towns also points to the near monopoly over religious institutions held by the Congregational Church, thus giving Congregational ministers—who were placeholders for the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests—a bully pulpit from which to affect public opinion in the group C towns.

2.3. Masters of the Senate

The commercial–cosmopolitan elite had a stranglehold on the state Senate. The commercial–cosmopolitan elite’s control over the upper chamber was linked to two factors: first was qualifications for holding office. State senators were required to have a freehold worth of £300 on property with a value of at least £600. Senators had to be residents of Massachusetts for at least five years, as well as residents of the constituency they represented (

Pole 1957). Senators often had homes in Boston or Salem in addition to second homes in the hinterlands. Many of the residents of group A towns had owned their homes for more than five years at the time of the ratification of the 1780 constitution. It was easy for residents of group A towns to meet the 5-year residency requirement. Polls in the least commercial–cosmopolitan communities often worked as itinerant farm laborers in their early years before settling in a specific location, putting them at a disadvantage in the early years of the Commonwealth. If a given farmer established their own farm in 1780, he was unable to run for office until at least 1786, given the Senate election cycle. The political institutions surrounding the Senate gave the elite a clear advantage in winning Senate seats while disadvantaging polls in the least commercial–cosmopolitan communities (see

Table 9 and

Table 10).

Second, a disproportionate number of senators were also judges of the Court of Common Pleas. The outright numerical advantage of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests in the Senate was compounded through placeholders. The combination of senators elected from group A towns and those who also served as judges represented roughly 70% of all Senate seats. Antifederalist senators held less than one-tenth of the seats in the Senate, while roughly half of the senators supported the new constitution of 1788.

10 Group A towns and judges often had aligned interests; throughout the 1780s, the Senate was a bulwark against measures sent up from the lower house that were contrary to the interests of group A towns and the judiciary, including proposals for tax reform, suspension of debt cases before the courts, once again implementing legal tender notes, and the softening of punishment for Shaysite rebels in 1786.

Seats in the House of Representatives—the lower chamber of the General Court—were more equally apportioned. The commercial–cosmopolitan interests were unable to monopolize the lower chamber with a numerical advantage. To the contrary, the western counties had forty-four percent of the eligible voters and were represented by fifty-two percent of the total representatives in the lower chamber. Representatives from Maine held ten percent of the seats in the House while having twenty percent of the population. As a result, the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests were overrepresented in the lower chamber. Nevertheless, the commercial–cosmopolitan interests were able to make inroads in the lower chamber through placeholders.

Like in the upper chamber, there is a significant number of representatives who were also justices (

Table 11). Representatives with dual status as justices accounted for one-third of the seats in the lower chamber. Justices of the peace and group A representatives combined represented more than half of the seats in the lower chamber. While in the upper chamber, the presence of senators with dual status as judges contributed to the commercial–cosmopolitan interests’ utter monopoly on the upper chamber.

However, in the lower chamber, the justices of the peace were not as reliable. The justices of the peace were sometimes swayed by the interests of their constituency. While the commercial–cosmopolitan interests were unable to exert sufficient pressure on the lower chamber to advance their agenda, they were able to halt unfavorable legislation when it reached the Senate and through their control of the governorship and the Governor’s Council.

Group A towns’ effective control over the legislature impacted national representation. The General Court, charged with electing representatives to the Confederation Congress, chose individuals along the same lines. Roughly four-fifths of the Confederation congressmen lived in group A towns. From 1788 to 1791, seventy-seven percent of representatives sent to the National Congress lived in group A towns.

In controlling the upper chamber outright and having significant influence in the lower chamber, the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests set the agenda, controlled policy, and halted countervailing interests. In also controlling the executive branch and the judiciary, the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests cemented their advantages over the least commercial–cosmopolitan communities.

2.4. Control of the Press

Group A towns were the informational epicenter of the Commonwealth. The widespread circulation of newspapers and magazines in group A towns served as a unifying force for the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. In the eleven years between 1780 and 1791, all of the newspapers and magazines published in the commonwealth were published in group A towns (

Table 12). These publications were owned and operated by residents of group A towns. Furthermore, advertisers in the press were merchants, artisans, and other service-based professionals who overwhelmingly lived in the group A towns. The press’s dependence on advertising revenue gave further strength to the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests in controlling

what and

how information was communicated. The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests were able to make the case for their programs and policy positions through propagandizing in newspapers and magazines.

A notable example was John Adams’ Defense of the Constitutions of the Government, of which four-fifths of all subscribers lived in group A towns. The concentration of periodicals in group A towns highlights the cultural sensibilities and learnedness of those individuals living in group A towns. This also highlights the remote desolation in which many of the residents outside group A towns found themselves.

The press served as a means to inform and unify constituents holding shared interests and thus the press, and those who controlled the press were able to shape public opinion (

Bachrach and Baratz 1962;

Lane 1965;

Zaller 1984,

1992). In a context without parties, periodicals served as a form of quasi-party organizing. In the case of political parties, party newspapers and pamphlets served to counteract the influence ofthe elite press. However, in the preparty era, the elite press dominated communication in Massachusetts and, as a result, had a high degree of influence over public opinion and thus the policy agenda.

The least commercial–cosmopolitan communities had a dearth of periodicals. Even if residents of one town managed to come together for a convention and agreed upon grievances and action steps, the residents of an adjacent town were unaware and thus unable to participate, thus fracturing the less commercial–cosmopolitan interests. Without periodicals, the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests were unable to get their constituents on the same page. Without periodicals, those same interests were unable to promote particular candidates or advocate for or against particular bills.

In controlling the press, the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests controlled what information was shared. In the eleven years from 1780 to 1791, the press did not cover the proceedings of the General Court. Constituents were unable to know the roll call votes of their particular delegates. During those same years, the Senate did not keep a journal, and the House kept an unpublished journal of its proceedings. Constituents had no way of knowing the specific work of the General Court. Additionally, the press did not publish details on the holders of the Commonwealth’s debts or other details regarding the financial status of the state. Furthermore, the state government did not publish such financial information independently. As a result, the details of the legislature and the state’s finances were obscured from public view. Consequently, information was doled out in the currency of social contact—valuable information was transmitted by word of mouth.

Those with social contacts in public office were able to find out the internal details of the legislature and the state government. The members of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests had a high degree of social contact with government officers, judges, and delegates to the General Court, with many group A residents serving in such capacities. As a consequence, members of the group A towns often had greater access to valuable information. This valuable information was then shared through an informal network of commercial entrepreneurs, public officers, and learned professionals across the state. That same information was kept hidden from other citizens, particularly those citizens in the communities outside group A towns.

The matter of communication was further exacerbated by the mechanics of mail. From 1786 and 1791, between 70% and 100% of post offices were in group A towns. As a consequence, group B and C residents were forced to travel into group A towns to retrieve their mail. The difficulty and length of travel in the era made the dissemination of information slow and sporadic. Without post offices or with few post offices by 1791, there was little ability to physically transmit information or disseminate a unified policy agenda, posing another obstacle for the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests.

Ultimately, the control of the press by the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests had two advantages: first, the periodicals circulated among the group A communities helped unify and put public opinion behind bills or policies that were advantageous to the group A interests. Furthermore, elite control of the press also allowed the few periodicals that were read by residents of the peripheral communities to only see one side of any given story; the opposing views, the views of the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests, were not included, thus giving additional advantage to elite’s in shaping public opinion.

The lack of press coverage on important matters before the legislature and the commonwealth’s financial status, the concentration of post offices in the group A towns, and the need for social contact with government officers to obtain such information, all point to the elite’s clear advantage in terms of information sharing.

2.5. Means of Ascent

Education was a social infrastructure that advantaged the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests in group A towns. The strong social ties in group A communities began in the private academies where the affluent sent their children.

11 The effects of the social ties formed in private academies and later in college on reproducing social class stratification are well documented (

Aries and Seider 2007;

Karen 1991;

Martin 2009;

Persell and Cookson 1985). Graduation from an elite private academy and Harvard were common features in the backgrounds of nearly the entirety of the governing class and the most commercial–cosmopolitan communities.

In the executive branch of government, all of the governors and lieutenant governors, with the exception of Benjamin Lincoln, attended Harvard College. Among the eight men who served on the supreme court between 1780 and 1791, only one was not a graduate of Harvard College. Additionally, more than three-quarters of the men selected to represent the commonwealth in the Confederation and National Congress were graduates of Harvard College. Seventy-five percent of Confederation congressmen from Massachusetts graduated from Harvard, and more than four-fifths of the congressmen lived in group A towns. The 1788 change to the popular election of congressmen did not increase popular control, despite reformers’ intentions. From 1788 to 1791, 77% of congressmen graduated from Harvard, and seventy-seven percent lived in group A towns.

12In attending Harvard College, many members of the commercial–cosmopolitan elite became socially acquainted and received similar educations. Moreover, affluent parents in group A towns established private schools for their children, which served as pipelines to Harvard College. From there, Harvard College served as the pipeline for commercial ventures, political careers, and lives of affluence, power, and influence.

In addition to the social reproduction of elite stratification brought on by elite schools and colleges, the nature of education in the era was itself a source of polarization between group A and group C towns. Schools and colleges created literate and informed citizens. Literacy allowed for citizens to read newspapers, magazines, political treatises, and the popular pamphlets of the era. The educational system of the day also contained a significant religious and moral component. This led citizens to develop ideas about political principles and how society should be governed. The payment of the state debt was seen not only in economic terms but also in terms of moral virtue. The issue of allowing the courts to sit in 1786 and 1787 in the face of armed insurrection was a matter of maintaining civil society and ensuring the continued and proper functioning of the judiciary, one of the three pillars of republican democracy. Ultimately, such issues are viewed in light of principled ideas about right and wrong. Such moral principles are commonly learned and discussed in the classroom of private academies and Harvard.

Schools and colleges provided a forum for discussions of social ills and the state of politics. Ultimately, the varied consequences of education, a privilege largely experienced by the most commercial–cosmopolitan class, created a chasm between the educated citizens of the group A towns and the often illiterate and poorly educated residents of group C towns, whose lives were dictated by visceral and practical considerations. Education also produced learned professionals who interacted socially, further bolstering the unity of interests and political advantages of the most commercial–cosmopolitan class.

The varied learned professionals who first formed social ties at Harvard College then had those social ties continued and reinforced by the many social, professional, and voluntary organizations of the era. Many such organizations had longstanding presences in Massachusetts society beginning well before the Revolution. The Masons, by the 1780s, were wholly integrated into elite society. Eighteen of the nineteen Masonic lodges in Massachusetts were located in group A towns.

13 As for the leadership, 100% of the holders of the office of Grand Master and other senior Masonic offices were residents of the group A towns (

Fleet 1793, pp. 80–81).

The merchant marine societies held significant sway in the ten leading shipowning towns, as well as in the ninety additional shipowning towns. The marine societies function as an early version of an industry lobbying group, promoting the cause of merchant mercantilism and the interests of shipowning communities. The societies for advanced degree professionals—physicians and barristers—had officers and members that were nearly exclusively from group A towns (

Fleet 1792, p. 84). The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests controlled these organizations and used the organizations to their advantage in terms of political organizing. This gives the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests a platform for organizing in the preparty era, a platform for which the residents of the least commercial–cosmopolitan communities did not partake and were actively excluded.

Honorary and cultural institutions were also controlled by the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences was founded by the Massachusetts General Court in 1780. The Academy was directed by leading commercial entrepreneurs and learned professionals, exclusively from the group A towns. The ranks of the Academy were populated by placeholders and other learned individuals from group A towns. The Massachusetts Historical Society was founded by leading politicians in the 1780s and was charged with studying and documenting the history of Massachusetts. Charitable and voluntary organizations were founded by senior Congregational ministers with the financial support from the affluent residents in group A towns.

14 The Massachusetts Agricultural Society, an early version of the farm lobby, was founded and led by members of the most commercial–cosmopolitan class and hosted its regular meetings in central Boston (

Fleet 1792, p. 75;

Fleet 1793, p. 32).

15Professional, social, and voluntary associations in the early commonwealth unified the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. Strong social ties began with education in the private academies of group A towns and later in the ties formed at Harvard College. This foundation led to lifelong ties through professional and social organizations such as the Masonic Lodge, marine societies, merchant societies, physician and barrister associations, honorary societies, and charitable associations. Through the interactions brought on by such associations, the commercial–cosmopolitan elite were able to advance their economic interests through collaboration. In collaborating in business, society, and politics, the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests were able to monopolize the levers of power and exclude dissent, in this case, the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests.

3. Legislating Without Parties

The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests are organized in primitive fashion compared with modern political parties. Furthermore, any organization of the most commercial–cosmopolitan was, in principle, non-political. The basis of the organization of the Massachusetts elite was through the natural forms of social and institutional organizing that were commonly found among elites. Such an organization became political in Massachusetts because there were no formal parties, and the elite’s social infrastructure served political ends. As a result of their non-political associations, the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests controlled the levers of political power—the General Court, the judiciary, the executive, the Church, and social and educational institutions—thus allowing for the implementation of favorable policy. The most developed interests were able to pass laws to consolidate the commonwealth’s debt and pay it back at a high rate of interest—to the benefit of speculators and lenders, who were residents of group A towns; pay the commonwealth’s share of Continental debt; quash tender laws; quash stay laws and debt relief; and raise taxes.

The least developed interests opposed all of these measures. The least developed interests tried to make their opposition known through their representatives in both chambers of the General Court. However, such efforts were futile. The most developed interests exerted their will in the lower chamber through placeholders; in the rare instance that a reform bill passes the lower chamber, it is swiftly quashed in the elite-controlled Senate. Politics without parties brought significant frustration to the least developed communities.

The political strength of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests came from their high degree of political involvement. Between 1780 and 1791, 98% of representatives from the 54 group A towns served for 9–11 years, as compared to the 201 group C towns, in which only 14% of towns had representatives serving 9–11 years. On the contrary, the bulk of towns in the 201 group C towns, 61%, sent representatives for 0–5 years. The 10 leading shipowning towns of Massachusetts—considered the most affluent—contained 12% of the polls while having 16% of all Senate seats and 11% of seats in the House. On the other hand, 57% of the polls lived across 243 non-shipowning towns and held 53% of the Senate seats and 64% of the seats in the House (see

Table 13).

The substantive political disagreements between the most and least commercial–cosmopolitan interests arose over matters of taxation, credit, and judicial policies, pitting the coalitions against each other. The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests supported a taxation program that favored commercial property, keeping taxes low on the merchant class. The ten leading shipowning towns within the group A towns contained 12% of the rateable polls in 1784.

16 This same set of individuals held two-thirds of commercial warehouse inventory in the state, 72% of the state’s total vessel tonnage, and 87% of the state’s wharfage.

Despite the significant concentration of commercial value among these 12% of rateable polls, total tax payments from this group only accounted for 14% of the state’s total tax bill (

Acts and Resolves 1782, pp. 903–06;

Hall 1972). Half of the collected tax revenue in the 1780s came from taxes on rateable polls and personal real estate. Taxes needed to be paid in paper tender, specie, or financial securities. The most commercial–cosmopolitan towns, with significant cash flow and affluence, had no issue meeting their tax obligations. However, in group C towns, hard currency or specie were nearly nonexistent.

The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests in group A towns were able to present a united front to achieve policies to their benefit or quash disadvantageous policies. The data presented in

Table 14 show the polarization between the poles of the commercial–cosmopolitan gradient. Furthermore, the roll call votes in

Table 14 are evidence that the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests were, in a large part, able to push through legislation in their interest and quash countervailing legislation. Ultimately, this points to the unified and organized front of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests.

Group C towns were unable to present a united front. The representatives sent to the General Court, while in principle sent to the General Court to represent their constituencies’ interests, often voted in line with the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests. The lack of information sharing and the absence of parties created a situation in which those individuals who had public profiles and were most widely visible won elections. Judges and justices were very often the most visible persons in the least developed communities. However, the interests of judges and justices were often in line with those of the group A towns and the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests and not in line with those of the constituents who elected them to office.

Looking at

Table 15,

Table 16 and

Table 17, one sees a granular breakdown of the western communities—the site of the bulk of the least developed communities—by commercial–cosmopolitan development, in the context of only western communities. Nonetheless, representatives from group A towns within the western counties voted at a lower rate than their counterparts from the western group B and C towns when considering bills that were favorable to commercial–cosmopolitan interests. One also sees that those representatives who were also justices or judges generally voted against such bills at an even lower rate than their colleagues who only served as representatives. Such voting patterns point to the judges and justices in their role as placeholders, even within the generally less developed western counties of Massachusetts. This data also illustrate the polarization between the two extremes of the commercial–cosmopolitan gradient.

Group C towns pushed for tender law reform to increase the legitimacy and flow of paper currency. However, the commercial–cosmopolitan elite opposed tender law reform, so as to keep the value of their assets high. Furthermore, the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests supported the judiciary’s judgments and the enforcement of debt judgments. The elite were opposed to legislation suspending debts. Underlying debt suits were the sanctity of contract, a central tenet of Common Law. Furthermore, the suspension of debt judgments would imperil the flow of credit upon which the commercial economy depends. Views on suspending debt were distinctly polarized along the commercial–cosmopolitan gradient (see

Table 18).

The elite control of major public offices; the outright control of the Senate; the substantial influence on the house; the network of placeholders in the church, business, and the judiciary; and control of the press and control of social, professional, and voluntary associations gave the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests the ability to implement their programs and laws that were to their advantage. The advantages of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests came at the cost of the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests. Without the ability to gather information, disseminate political ideas, and organize, the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests were unable to exercise influence in the political system and their frustrations began to accumulate.

In the years prior to the insurrection of 1786, questions pertaining to state and national taxation laid bare the deep chasm between the most and least commercial–cosmopolitan interests. The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests advanced a policy program that included legislation for repaying the state’s debt, as well as legislation for collecting direct and poll taxes to be used for paying the national debt. The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests pushed a narrative that rapid repayment of state and national debt would benefit Massachusetts’ economic health and that it was a moral imperative to repay the state’s debts. However, the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests were opposed to these measures, seeing such high taxes and moral imperatives as serving elite interests, enriching those already at the top. However, attempts to counteract the elite’s policy agenda by the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests were futile. The most commercial–cosmopolitan interests were organized and always a step ahead of the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests.

Bills for greater taxation passed through both chambers of the General Court with little ability of the least commercial–cosmopolitan to put a stop to such bills. The least commercial–cosmopolitan’s numerical advantage was ineffective because of placeholder representatives who voted in line with elite interests. Once bills passed the lower chamber, the outright monopoly of the Senate and the governorship by the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests ensured the smooth passage of bills. Between 1780 and 1786, three-quarters of the votes taken in the General Court pertained to bills regarding taxation, state and national debt, and private debt. Of the 20 bills regarding such matters, only 1 received consensus support. On 19 roll call votes, there was polarization between the most and least commercial–cosmopolitan interests, as displayed in

Table 14 and

Table 15. The same table also points to the binary nature of the polarization, with the greatest difference between the group A and group B towns. This evidence points to the fact that the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests attempted to get relief from their economic distress. Their efforts turned out to be futile.

4. Populist Backlash: From Discontent to Uprising

At the outset of the economic crisis beginning in 1780, Massachusetts farmers had faith in the political system to provide relief (

Starkey 1955, pp. 7–19). Between 1780 and 1786, rural constituents held scores of conventions, where grievances were aired and efforts were organized. Political conventions generated many and sundry petitions and letters with a unifying theme: rural communities were in distress and the state government was exacerbating the conditions. Records of such conventions show that the conditions farmers were most concerned with were private debts, burdensome taxes, lack of currency, and the courts (

Starkey 1955;

Richards 2003;

Warren 1905, pp. 5–7).

In 1781, attendees of political conventions in Hampshire and Berkshire counties declared the farmers’ opposition to the repeal of paper currency as legal tender. The farmers argued that the repeal of paper currency would cause further currency contraction, further depress farm prices, and render what little paper currency farmers possessed invalid in debtor’s court (

Taylor 1954). Aggrieved farmers at a convention in Lancaster sent a letter to their representative at the General Court, Ephraim Carter, with instructions to pass “a law to ease the burden of taxation upon the husbandman” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86). The letter also included instructions for “the abolition of the courts of common pleas and general sessions of the peace and a transfer of their jurisdiction to the supreme judicial court, and in other matters to justices of the peace” as well “the reduction of salaries” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86). To mitigate the effects of high taxes, Carter was instructed to use “the payment of fines into the public treasury and lighten the poll tax” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86). The letter reveals rural constituents’ distrust of distant power by instructing Carter to seek the “removal of the legislature to some other place than Boston” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86). The many and sundry instructions from the Lancaster convention point to rural constituents’ concern with taxes and court judgments, as well as emphasizing their desire for local governance.

By 1786, common men in the group C towns realized that participating through the conventional means of political change was in vain. Conventions that had once been the venue for civil political discussion became the venue for organizing armed insurrection. In August 1786, the participants of a convention in Hatfield drafted a pledge committing the signers “to prevent the sitting of the Court of Common Pleas for the county, or of any other court that shall attempt to take property by distress and to prevent at the risk of their lives and fortunes the public sale of property seized by distressed” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86). In September 1786, Job Shattuck sent a letter to the judges of the court on behalf of the rebels from Middlesex county, stating, “that it was the voice of the people of the county that the court of general sessions of the peace and of common pleas shall not sit in this county until such time as the people shall have a redress of a number of grievances they labor under at present, which will be set forth in a petition or remembrance to the next General Court” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86).

At a Hampshire county convention of distressed farmers, the participants wrote, “the expensive mode of collecting debts which by the reason of the scarcity of cash will fill the gaols with unhappy debtors and thereby hinder a respectable body of people from being serviceable either to themselves or community” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86). In January 1787, attendees at a convention in Brookfield sent a petition to Governor Bowdoin demanding the “[adjournment] of the court of general sessions, and of the common pleas, for the three western counties, until after the next general election and session of the legislature” (

Smith 1948, pp. 83–86). The petitions generated from political conventions were useful only insofar as they were acted upon by the politicians receiving the petitions—in the case of Massachusetts in the 1780s, not at all.

Popular discontent became popular insurrection. The insurrection in Massachusetts began in late August 1786 and lasted until August 1787. The insurrection persisted, and farmers in the western counties of Massachusetts continued to perceive their grievances as falling on deaf ears.

Governor Bowdoin convened the legislature in November 1786 to address the ongoing insurrection. The conservative elite in Boston, led by Samuel Adams, were vehemently opposed to appeasing the farmers and argues for harsh punishment for agitators, stating, “in monarchies the crime of treason and rebellion may admit of being pardoned or lightly punished, but the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death” (

Pencak 1989, p. 64;

Richards 2003, p. 16). Governor Bowdoin, while not sympathetic to the farmers, was more interested in bringing the insurrection to an end and restoring law and order. The legislature passed a series of measures that were not as harsh as what Adams wanted but instead reflected a compromising approach (

Richards 2003, pp. 16–17).

To help farmers, the legislature passed measures to ease the tax burden by allowing payment in paper currency, specie, land, services, or other assets. The legislation also extended the due date for current taxes from 1 January to 1 April 1787. Moreover, the legislature approved a plan to sell 1800 square miles of Maine to pay publicly held debt. In terms of private debt, a measure passed postponing legal fees for two years for farmers brought to the debtor’s court. Additionally, between January and September 1787, farmers were permitted to pay private debts with land and other property (

Cain and Dougherty 2016;

Richards 2003, pp. 16–17).

On the other hand, the legislature also passed measures to help the state quash the rebellion, inflaming the polarization between the two coalitions of interests, elite and common. In a bill passed on November 10, the legislature suspended habeas corpus until 1 July 1787, and gave Governor Bowdoin the right to imprison “all persons whatsoever” who were dangerous to the public welfare (

Richards 2003, p. 19). Another such measure, the Riot Act, gave legal immunity to sheriffs for killing rebels who resisted capture or failed to disperse. The Riot Act also specified punishment for captured rebels: the forfeiture of their land, personal property, livestock, and other goods to the state. Furthermore, rebels “shall be whipped 39 stripes on the naked back, at the public whipping post and suffer imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months”, as well as an additional thirty-nine lashes every three months during imprisonment (

Richards 2003, pp. 16–17). The legislature also passed the Disqualification Act, barring all rebels from serving on juries, holding office, or voting in elections (

Richards 2003, p. 33).

The legislature also passed the Militia Act, punishing those members of the militias who defected in support of the farmers, proclaiming “whosoever officer or soldier shall abandon any post committed to his charge, or shall speak words inducing others to do the like in time of engagement, shall suffer death” (

Richards 2003, p. 17). The Militia Act spoke to a serious obstacle for state leadership in quashing the insurrection: the defection and weakness of the state militias.

In the western counties, militiamen were reluctant to comply with the orders of the state leadership in Boston. The militias were composed of local, able-bodied men. The very men who were expected to form the militia were often sympathetic to rebel farmers, and many were active in the rebellion. Militias in the eastern counties were compliant with Governor Bowdoin’s orders. However, the few compliant militias were ill-equipped. The Continental government had an arsenal with ample artillery in Springfield. However, the state did not have access to the artillery in the Springfield arsenal without the permission of Secretary of War, Henry Knox, who was unwilling (

Richards 2003, pp. 23–25).

Without effective state militias to quash the insurrection, Governor Bowdoin hired a mercenary army of 4400 men. The mercenary army was summoned without legislative authorization, thus making no funds available to pay for the mercenaries. Instead, the governor contributed £250 from his own pocket and gathered an additional £6000 from businessmen in Boston. Governor Bowdoin and General Lincoln, who were in charge of the mercenary army, persuaded businessmen to contribute by justifying the contributions as a small amount to pay in order to preserve the bulk of their fortunes from the effects of the insurrection (

Richards 2003, pp. 23–25). The use of private donations from businessmen points to the divide between the most and least commercial–cosmopolitan communities. Moreover, it points to the ability and willingness of the elite to organize collectively for the sake of their best interest: the resumption and maintenance of law and order, the absence of which would negatively affect commercial enterprise.

17Measures passed by the legislature and the hiring of a standing army further stoked the agitation of farmers in the western counties. The deployment of the mercenary troops to the western counties was initially met by rebel farmers in kind, with an escalation in violence. However, the rebels were overwhelmed by the better-equipped and better-trained troops.

Shays’s Rebellion began with the bravado of halting the courts, causing the breakdown in law and order. Shays’s Rebellion ended in mundane failure. The insurrection was finally put down by the mercenary army in a string of ever smaller skirmishes across the Berkshires in the Spring and Summer of 1787. The rebels did not get what they wanted. The taxes, debts, courts, and system of representation that frustrated common men and led to insurrection remained in place.

The War for Independence promised greater equality and freedom from tyranny. Yet, for the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests, life under colonial rule and reality in the early Republic were starkly similar. The Revolution had been an elite transition.

4.1. The Tyranny of Geocracy

In 1780s Massachusetts, polarization was about where one lived. Where one lived determined one’s social place, one’s economic fate, and ultimately, one’s political fate. The variables described in previous pages, all of which demonstrated the formidable advantages of the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests, show the power of geography in early New England.

The structure of representation in Massachusetts advantaged the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests and precluded the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests from active political participation. The advantages of the elite were reinforced by their physical proximity to each other and the venues of government: the General Court, commercial centers, social clubs and associations, the state house, the press, and the church.

The utter inability of commercial–cosmopolitan interests to mount a response stemmed from the geographic mechanics of political participation. For example, rural communities, where the bulk of group C towns were found, had no post offices or government services. If one takes a look, for example, at the small coastal town of Hull, a group C town across the bay from Boston, one can see the effect of location on political participation. By land, Hull is roughly 43 km from Boston. Using approximations from historical records, a stagecoach could travel roughly 60 km if traveling for a full day along a well-worn path.

18 This does not take into consideration the weather and road conditions of less-worn paths most typically used by common men.

19 The weather played a major role in the ability to travel—a meter of freshly fallen snow, not uncommon in a typical New England winter snowstorm—entirely obstructed travel for weeks.

20 Rainstorms could muddy the paths, breaking the wooden carriage wheels, stranding travelers along the route. Thus, a resident of Hull traveling to Boston needed to wait for good weather and then dedicate much of a day to travel each way. A simple trip to Boston was a multi-day journey. Today, residents of Hull may reach Boston either by motor vehicle, taking roughly 45 min, or by ferry, taking roughly 23 min.

If a common man in Hull wished to retrieve his mail and newspaper at the nearest post office 12 km away in Hingham (a group A town), he needed to account for his round-trip travel—roughly 24 km. A 24 km round trip took roughly 10 h, not including time spent in Hingham retrieving the mail and letting the horses recover for the return trip.

21 Ultimately, the simple trip to Hingham by a common man from Hull may have taken as many as 12 h. To put this in perspective, today, a one-way trip by motor vehicle from Hull to Hingham takes roughly 16 min.

A common man, a poll, residing in New Salem (a group C town) and answering a summons to the Court of Common Pleas needed to travel to the county seat at Northampton, 38 km away. If such a common man was traveling alone by horseback, he may have traveled on average roughly 32 km per day. Thus, a one-way trip from New Salem to Northampton required an overnight stop. To put this in perspective, today, a one-way trip by motor vehicle from New Salem to the Northampton courthouse takes roughly 38 min.

Geography was a significant factor for residents of the least commercial–cosmopolitan communities in a way that the most commercial–cosmopolitan communities did not face. Casting one’s ballot, attending conventions, court hearings, running for office, paying one’s taxes, and other political participation, or obtaining government services, required complex travel logistics. The relatively vast distances of Massachusetts and laborious forms of travel further weakened the political strength of the group C communities.

Low voter turnout was pervasive among polls in the group C communities, particularly those in western Massachusetts and the district of Maine. Without political parties, there was no means of political organization. The absence of organization meant the absence of the tools used for mobilizing voters: policy platforms, political advertising, endorsements, vote canvassing, and party conventions. Residents of group C communities found it difficult to acquire information about the government because of the lack of transparency and press coverage and the lack of available periodicals in group C communities. Underlying the lack of informational dissemination was the fact that many of the group C residents were uneducated and illiterate, causing them further confusion about the intricacies of tripartite republican government.

As a consequence of this lack of available information and the lack of understanding, political participation was depressed among group C communities. Voter turnout eventually increased after 1787 as the result of persistent and accumulated frustrations held by the least commercial–cosmopolitan interests, as a backlash to the response of the Bowdoin government’s heavy-handed military response to the Shays’s Rebellion, and as a consequence of reforms to voting rights: the lowering of property requirements and the waiving of debt issues as cause for disenfranchisement.

22 4.2. A Tale of Two States

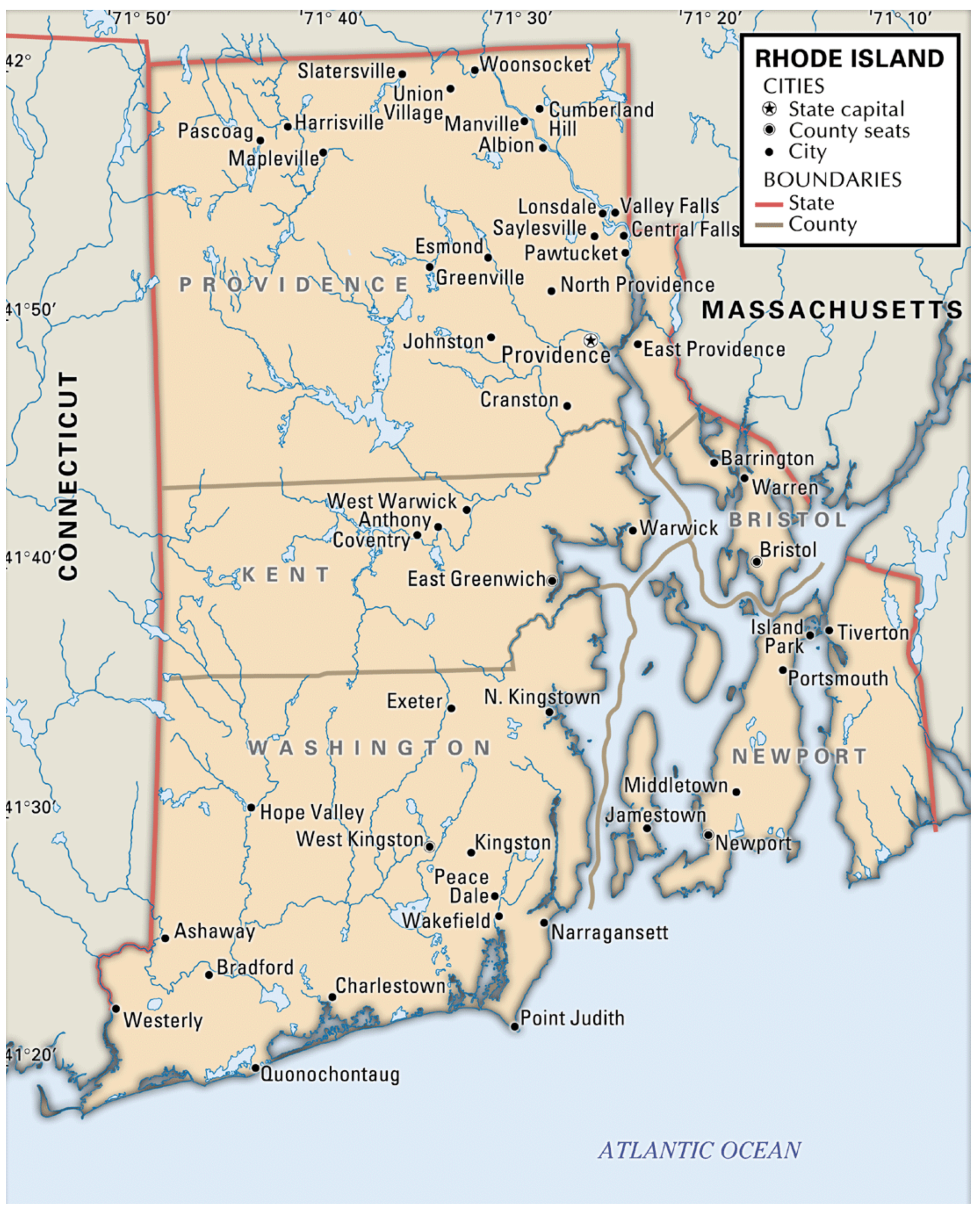

During the same years and despite facing similar conditions, insurrection was averted in the neighboring Rhode Island. In Rhode Island, geography prevented polarization. Comparing Massachusetts with its smaller and less populous neighbor, Rhode Island, illustrates how the geographic mechanics of political participation fundamentally altered the economic and political experience of Rhode Islanders in the tumultuous 1780s.

In Rhode Island, the distance between the seat of state government, Providence, and the most distant location by radial distance was roughly 77 km. All other towns fell within a radius of less than 77 km of the capital. The closer proximity of polls and the population as a whole led to greater social integration and thus a more egalitarian political landscape in the 1780s.

The same natural advantages that give the most commercial–cosmopolitan interests in group A towns in Massachusetts an upper hand—significant social associations, press availability, and physical proximity—applied to the whole of Rhode Island (see

Table 19 and

Figure 1). Rhode Island possessed seven newspapers. However, Rhode Island newspapers were widely distributed across the state because the distances were significantly smaller, thus making distribution easier. Additionally, post offices were more widely distributed and in closer proximity to the population, facilitating the dissemination of information. Furthermore, Rhode Island did not possess the same entrenched elite class that is found in Massachusetts. Boston was the focal point of British control during the colonial era and was long a economic and political engine of New England. Providence was substantially smaller geographically, with fewer residents and less commercial activity. Without a longstanding and entrenched elite class, there was greater space for common men to participate. The greater political integration facilitated by the relative geographic proximity of the population was evidenced in the political events of 1780s Rhode Island.

In 1785, distressed rural residents of Rhode Island formed the Country Party. Common people living outside the urban centers were able to do so because of more fair access to periodicals and more fair access to information in such periodicals, thus helping get polls on the same page. In 1786, the Country Party swept statewide elections and took control of the legislature, campaigning under the slogan “to relieve the distressed” (

Richards 2003, p. 83). The ability of the rural communities to hold a majority in the legislature was due to Rhode Island’s low requirements for voting and holding office. Qualification to vote requires property ownership of £40 or annual rent of at least £2, as well as not having any delinquent tax debt (

Hough 1872, pp. 246–71).

23 Veterans of the Revolution and currently enlisted troops were permitted to vote regardless of income or assets. Moreover, private debts, delinquent or otherwise, were not a cause for disqualification. Despite the rule on delinquent tax debt, it was rarely enforced. All polls were able to hold elected office without additional qualifications. Low barriers to voting and holding office allowed for rural constituents to participate in politics.

The allocation of representation was more evenly distributed in Rhode Island. Elections for governor, lieutenant governor, the House of Representatives, and the Senate were held annually. Representatives in the lower chamber were elected at the town level, and the number of representatives from each town was contingent on the population, with each town receiving at least one representative. The number of representatives from any given town could not exceed twelve or one-sixth of the total number of representatives in the lower chamber. The lower chamber was limited to seventy-two representatives. Each town elected one senator for the upper chamber, with ten senators in total. The lieutenant governor, elected separately in statewide elections, presided over the upper chamber (

Hough 1872, pp. 246–71). In 1786, the Country Party held forty-five seats in the lower chamber and five seats in the Senate. The Country Party won majorities in either one chamber or both in each annual election until 1795. The ability of rural constituents to be aptly represented in the legislature gave voice to the concerns of common people in Rhode Island and served as a pressure valve, relieving frustrations.

The effective representation of rural constituencies in the legislature yielded significant relief for those communities. In 1786, the Rhode Island legislature passed laws instituting the legal status of paper currency, increasing access to currency for farmers, and enforcing the legitimacy of paper money (

Szatmary 1980). Additionally, the legislature voted not to make simultaneous payments on its war debt and its share of the continental government’s war debt. As a result, the tax burden was far lighter for Rhode Island’s constituents.

The use of paper currency as legal tender was of particular consternation for the merchant class in Rhode Island. The merchant class preferred specie, gold and silver coins, because of their value in global trading markets. Merchants often attempt to skirt the tender law by refusing to accept paper money. The legislature answers with strict legislation punishing creditors or merchants who refused to accept paper currency with a fine of £100 per instance of refusal.

24 Creditors and merchants who refused paper currency were banned from seeking elected office and had commercial licenses revoked, including the prohibition of sailing in or out of Rhode Island ports, a draconian measure in the day (

Szatmary 1980, pp. 47–55).

Figure 1.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

c. 1785.

25

Figure 1.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

c. 1785.

25

Two additional proposed bills point to the egalitarian nature of the legislature. First was a bill proposing a requirement for all constituents to swear an oath supporting the use of paper currency. Failure to take the oath resulted in the suspension of an individual’s voting rights. Another bill proposed seizing all commercial enterprises, giving control of trade to the state government (

Szatmary 1980, pp. 47–55). The consideration of such measures indicates the legislature’s impatience with exploitation and its zeal in defending the interests of common men.

Further helping distressed common men was the legislature’s supremacy over the judiciary. The Rhode Island Constitution did not vest the judiciary with separate and independent power (

Hough 1872, pp. 246–71). Instead, the state constitution vested the legislature with authority over judicial matters.

26 The legislature was responsible for appointing justices and was allowed to override court decisions. Once the Country Party was in the majority in the legislature, court decisions perceived to favor commercial interests and disadvantage farmers were swiftly reversed by the legislature. In a 1786 case involving a merchant’s refusal to accept paper currency as payment, a local court dismissed the case without remedy. The legislature overrode the court’s decision, ordered the merchant to accept paper currency, and provided compensation as a remedy to the plaintiff (

Szatmary 1980). Furthermore, the justices responsible for the decision were summoned to the legislature, dismissed from their positions, and issued criminal charges, evidencing the pro-debtor and populist orientation of the Rhode Island legislature.

Massachusetts and Rhode Island faced similar economic circumstances in the 1780s. Both were new states within the nascent nation (for a geographic, visual comparison, see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Both had significant state debts and had large sums to pay for the Continental government’s requisition. The credit contraction and economic fallout that impacted Massachusetts, from the wealthy merchants and landowners down to the subsistence farmers, also impacted Rhode Island. The states diverged in their reactions to such an economic fallout. In Massachusetts, group C towns were unable to mount a response because of the lack of ability to communicate, receive information, and mobilize for collective political action. At the same time, most commercial–cosmopolitan interests monopolized the levers of power, further weakening the political power of common men. Massachusetts’ common men also contended with the vast distances over which they had to travel to participate in politics and governance.

Figure 2.

Comparative view of Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

27

Figure 2.

Comparative view of Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

27

Figure 3.

State of Rhode Island.

28

Figure 3.

State of Rhode Island.

28

Rhode Island’s common men contended with a far smaller geography; Rhode Island is roughly one-fortieth the size of Massachusetts (for a visualization of this, see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Rhode Island’s population was roughly one-sixth that of Massachusetts. Rhode Island also possessed seven post offices, evenly distributed throughout the state.

29 On average, each post office served 7564 residents. The newspapers published were better able to reach a broad swath of the population. Many newspapers included portions that were specifically dedicated to rural life.

30 Moreover, Rhode Island papers provided coverage of political affairs in the state. Among the most popular Rhode Island periodicals,

The United States Chronicle: Political, Commercial, Historical, provided Rhode Island residents with a thorough breakdown of the political happenings of the day; vote counts, names of representatives, bills passed, vetoed, and signed into law. In so doing, Rhode Island residents were able to have an understanding of the political landscape in their state.

A confluence of variables yielded better representation of common men in Rhode Island: more evenly distributed allocation of seats in the legislature, low barriers to qualify to vote and hold office, better press coverage of politics, and the benefits of a relatively small geography, and shorter distances to travel to participate in politics and retrieve periodicals and other forms of communication through the postal service. The arrangement of such variables in Rhode Island served as a pressure valve for the frustrations of Rhode Island’s common men. The relief of common men’s frustrations prevented persistent and accumulated frustrations from boiling over and triggering insurrection.

5. Discussion

In the 1780s, politics was geographic. Where you lived determined what representation you obtained. At the beginning of the nation, Americans struggled with how to extend the Republican ideals of the Revolution across the vast land that was now theirs. The new nation was larger than the ideal size for republics claimed by Montesquieu and Locke. In the first years of the Republic, states of different sizes faced different problems (

Zagarri 1987, pp. 4–5;

Soja 1971).

Policymakers in small states deal with a generally homogeneous and static population. Cities and towns are densely packed, there is limited land in which to spread out, and no residents tend to possess large tracts of land. In this context, political institutions do not need wholesale reforms. Rather, policymakers in small states like Rhode Island would “tinker” with their political institutions; they passed relief bills, formed new political factions/parties, and changed the composition of the courts. All of this took place well within the parameters of routine Republican government. In the context of small states, cyclical elections sufficed to usher in change. In small states, the apportionment of representation by geography worked both in principle and in practice. However, in large states like Massachusetts, such tinkering and geographic representation did not suffice.

Geographic representation was incongruent with reality in a large state like Massachusetts. Policymakers in Massachusetts confronted a different set of problems: a significantly larger and growing population and demographic and socioeconomic diversity to a much greater extent than in their small neighbor, Rhode Island. The dispersed population over great distances made mobility a central issue. As a result of the unstable and evolving communities in Massachusetts, legislators incorporated representative institutions based on population rather than solely on geography. In name, this was represented by demography and population. However, in Massachusetts, representative institutions determined by demography and population were ineffective in practice because of the ability of elites to manipulate Republican government through placeholders and the exercise of influence and affluence.

The ineffectiveness of Massachusetts’ representative institutions was a consequence of the lack of parties. Between 1780 and the summer of 1786, roughly one-third to one-half of Massachusetts’ population lived in the less developed parts of the state. While in principle they had representation, sending delegates to the General Court, and while formal rules on voting were in the books, such rules were rarely enforced. At first glance, one would not understand why frustrations accumulated among the constituents in Massachusetts’ less developed areas. Despite Massachusetts’ policymakers reforms to expand voting further in 1787 and further apportionment on the basis of demography and population, such reforms were meaningless without oppositional political organization.

The absence of formal parties, as we understand parties today, allowed the most developed communities to exercise their natural advantages: their interconnectedness through education, professional ties, social associations, and shared interests. The elite were able to exercise their will by holding important public offices and putting into office a sweeping network of placeholders. Such placeholders, on paper, represented a particular, less-developed community, but in reality, were planted to bolster the political strength of the elite. The unified front put forward by the most developed communities was bolstered by the control of the press. The press was used to get residents on the same page in the most developed communities. Furthermore, the issue of mobility again further expanded the chasm between communities, making information difficult to access for those outside the most developed communities. Moreover, the press did not provide crucial political information, thus denying common men the ability to learn about their government or know how their delegate voted on a given bill.