1. Introduction

Access to raw materials has always been one of the main drivers of economic growth. Although the relationship between mineral resources and economic development can be traced back to the early stages of human history, each historical period can be related to different types of resources derived from mines and excavations. Based on this evidence, it can be seen that the geography of mineral resources has influenced economic development and relations between producing and consuming countries, often causing complex international relations as well.

When analyzing European countries and US case studies (

Agovino et al. 2019), it can be found that in the early phases of the Industrial Revolution, the relationship between economic development and mineral resources was strongly influenced by their geographical availability, and in the subsequent phases, commercial relationships between producers, transformers, and consumers, together with colonial politics and commercial agreements, played an increasing role. In this new age, efficient transport and infrastructure, migration and social issues connected to miners, financial and insurance services, and the overall international technical and scientific debate were strategic factors affecting development. Data and information connected to the above-mentioned factors, better if studied at a temporal and geographical level, can be adopted today to answer different research questions regarding the mining sector from a historical perspective.

In Italy, where high imports of energy sources have always been a major issue, the island of Sardinia, with its large variety of mines, combined with a role in Mediterranean trade and logistics that can be traced back to the time of the Phoenicians, has always had a significant role in the sectors of extraction and commercialization of mineral and energy sources. For these reasons, Sardinia offers a perfect case study for academic research regarding the history of the mining sector in Italy and in the Mediterranean Sea.

Even during the energy transition from wood to coal, which is considered a main determinant of the rapid European economic growth from the XIX century until WWII, Sardinia Island played a strategic role with reference to the Italian scenario (

Bardini 1998). In fact, during this period, the availability of coal mines was a key factor, with the use of coal as the energy source for new steam engines the necessary condition for the development of modern industries (

Bartoletto 2013), and since Sardinia Island was indubitably the most fruitful and rising coal extraction site in Italy, its coal mines were at the core of the energy transition in Italy.

In fact, in Italy, where the scarcity of energy sources has always represented a limit on industrialization and formed the main reason for the country’s slower development path compared to England and Germany, the transition, again, could have negatively affected the potential of the country to compete at an international level. In this phase, especially during the fascist period, the so-called

Ventennio—1922/1943—(

Gentile 2022), large efforts were made to improve the productivity of Sardinian historical and new coal mine districts. This was under the application of the fascist economic policy addressed towards the exploitation of Italian resources and which intended to make Italy self-sufficient—the Autarky.

However, there was a thin line between the real possibilities of the Sardinian mining sector to support this effort and what fascist propaganda showed. In fact, even if Sardinia opened a window on Italy’s chances of supporting the economic transition, this did not mean that the Sardinian coal sector could support this crucial step in achieving total autonomy from imports and technological innovations.

The Sardinian experience was adopted as a success case in the fascist communication strategy, and the island itself, with its state mines and mine villages, was depicted as a role model with reference to production, support for the national industry, and several social issues that were connected.

The research hypothesis here was that, as emerges from fascist propaganda, the Italian coal sector, thanks to the opening of new mines and the capacity for modernization resulting from Italian technological advancements, had the strength to counteract the sanctions imposed in 1935 by the League of Nations, and that Italy was therefore able to face the energy transition in total autonomy. The thesis of this research was that, not only did Italy remain, even during the Ventennio, dependent on the international energy market but also that the technological advances much publicized by fascist propaganda were the result of cultural and technological exchanges with foreign countries. To demonstrate the thesis, data regarding Italian coal imports and consumption and some technical reports regarding technical updates in the mining sector on Sardinia Island were analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

This article, after having introduced the energy transition from wood to coal, and its effects on the international markets for energy at a global level and on the economies of producers and consumers, focuses on this new challenge in Italy during the

Ventennio with a special focus on the Autarky. Then, the Sardinian case study with a special focus on its role within the fascist propaganda regarding the energy transition is introduced. In this first phase, the thesis of this research is illustrated based on both bibliographic and archival sources, and for the very first time, the correlation between a global phenomenon, the Italian economic and political situation, and its interpretation in the fascist propaganda is introduced. Then, based on some unpublished data regarding coal consumption/imports during the

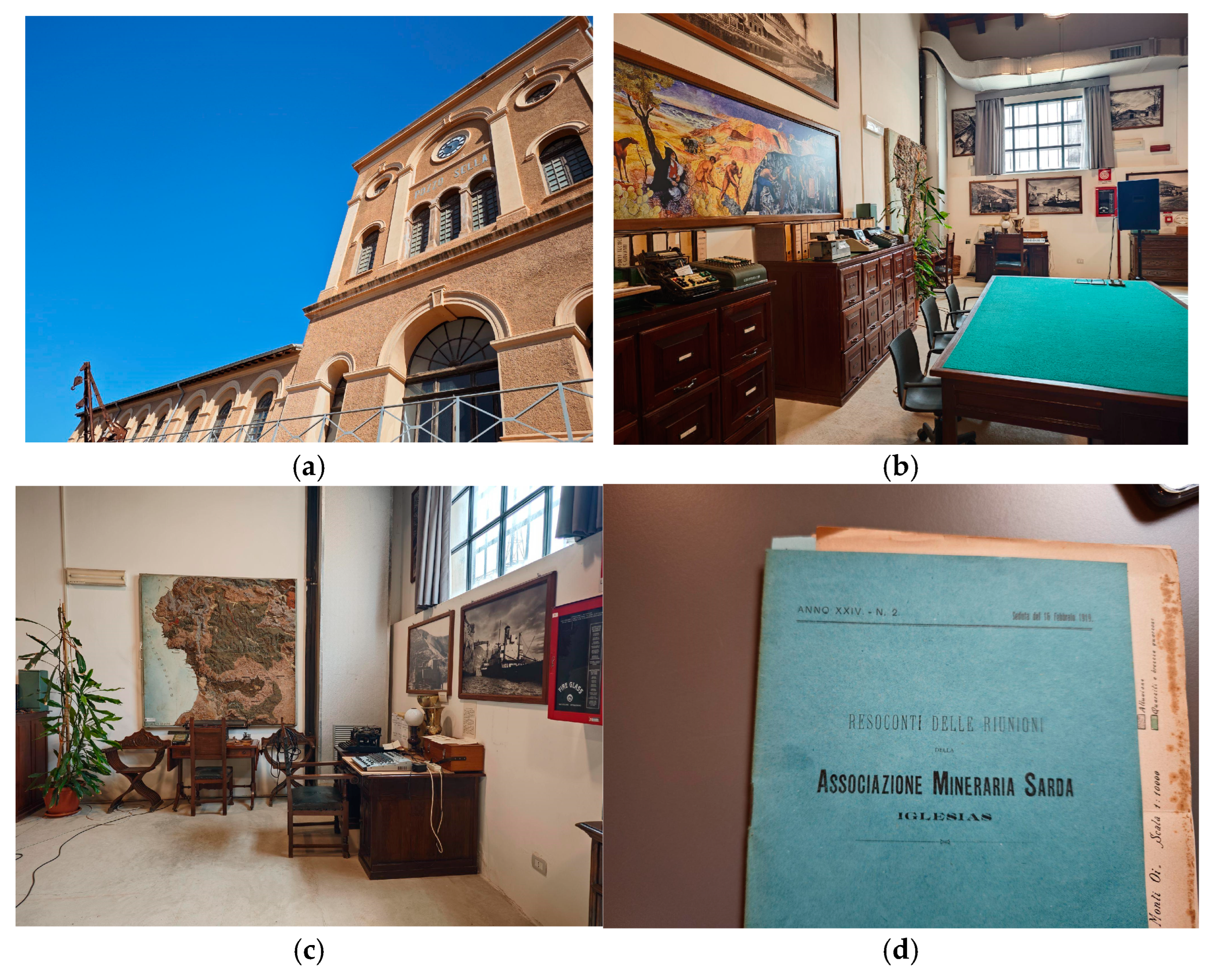

Ventennio, compared with data regarding coal production in Sardinia, and the analysis of the results of archival research carried out at the Mine Historical Archive from the Italian Mine Company, IGEA (

Società Italiana Miniere (IGEA) 2024), regarding technological/managerial updates from abroad, this research refutes the thesis.

Imports of coal during the fascist period were reconstructed through the analysis of statistical data included in “Movimento Commerciale del Regno d’Italia” (Trade movement of the Kingdom of Italy) published by the Ministry of Finance. These data were compared with the database constructed by the Bank of Italy on coal imports during the same period (

Federico et al. 2011). The results of the two different sources largely align. As for coal consumption during the years 1922–1940,

Bartoletto (

2005) constructed the data for types of coal through the analysis of the Bulletin of the Coal Committee (

Bollettino del Comitato Carboni n.d.) and reports published by Giorgio Pluchino, Director of the Italian Coal Committee (

Pluchino 1955).

Coals with different qualities have different heat contents. For this reason, it could be misleading to sum the quantities expressed in metric tons, and so we used energy conversion factors to express total imports and consumption of coal. The same was true when we summed different energy carriers, which are expressed in different units of measurement, such as electricity expressed in kWh, or oil and coal measured in tons. The energy conversion factor that we adopted was the Mega Tons Oil Equivalent (Mtoe).

With reference to data from the IGEA (

Società Italiana Miniere (IGEA) 2024), information published on bulletins that reported “news” regarding technological and managerial updates from abroad in the period of 1924–1937 was studied. Data were summarized in Excel tables whose fields corresponded to the most significant information provided in the reports: year of the report, country, study of the economic context at a comparative level, technical/scientific studies and experiments, commercial relationships, production and market trends, mining sector, total production in general or per capita, distribution network, technology adopted, machinery adopted, management of critical issues, morbidity, and description of the mine. In the first phase, the fields of this table were very detailed and contained all the information that the Sardinian Mining Company could acquire from the reports. In a subsequent phase, a classification of the recurring topics, critical issues, and technical solutions was carried out and results from this screening were examined from both a qualitative and statistical point of view. Once all the most relevant elements were analyzed, their descriptive and statistical analysis was carried out by adopting only the topics taken into consideration in the individual reports. Summary tables were compiled and data analyzed at a comparative level.

This article is structured as follows:

Introduction to the energy transition with a special focus on Italy;

The Sardinian case study;

Analysis of data regarding Italian coal imports and consumption during the Ventennio;

Analysis of data regarding scientific and technological progress during the Ventennio in the mining sector.

At the end, data resulting from the elaborations are discussed and conclusions are elaborated.

3. The Energy Transition: From the Global Scenario to Italy

Energy transition corresponds to a change in the composition of the energy balance, both at world level and with reference to a single country. The key elements of energy transition are the introduction of new energy sources and new technologies enabling the use of new energy carriers (

Bartoletto 2013). The first technical watershed in modern history took place with the development of steam engines, electricity, water turbines, internal combustion engines, inexpensive steel, aluminum, explosives, synthetic fertilizers, and electronic components (

Smil 2003,

2005). The transition from traditional energy sources (wood, water and windmills, working animals) to fossil fuels was very complex and resulted from several factors, such as changes in the structure of the economy and the increase in population (

Fouquet 2008). Worldwide, especially in Europe and the United States (

Bartoletto 2018;

Schurr and Netschert 1960), over the past two centuries there has been an enormous growth in fossil fuel consumption: first coal and later oil and natural gas. Currently, fossil fuels represent about 80% of the world total consumption (

IEA 2023), but at the beginning of the XIX century, the energy balance was dominated by traditional energy sources, especially firewood. The rapid growth of the population was one of the main factors that drove the transition from wood to coal. The need to produce more agricultural products to satisfy the growing demand for food, especially in Europe, led to the destruction of large forest areas to make fields for cultivation. For this reason, wood, which was the main energy source until the Industrial Revolution, became scarce. To satisfy the growing energy demand from new industries and the rising population, the transition to coal was necessary. In the United Kingdom, coal was seen as “being a God-given gift that led to world domination” (

Mathis 2020). Indeed, since the XVIII century, the UK has consumed and exported large quantities of coal thanks to its abundant coal reserves (

Fouquet 2008). Coal mines and coal miners shaped the energy history of the United States starting from the last decades of the XIX century to the end of WWII (

Kahle 2024).

Compared to the US and other European countries, Italy was a latecomer in industrialization, and wood played a central role in the Italian energy balance until WWI. The energy transition from wood to coal and the simultaneous increase in energy demand had a great impact on the Italian energy sector. Not only has energy consumption increased in total and per capita terms, but the relative importance of individual energy sources has also changed. In 1870, wood represented about 50% of the total energy supply in Italy, while coal accounted for about 7% (

Bartoletto 2005;

Bartoletto and Rubio 2008). The Italian energy system rapidly changed in the so-called Giolitti period (1900–1913) (

De Grand 2000). During this timeframe, new industries in the mechanical and steel sectors were established and the growth of coal consumption and imports was very fast (

Figure 1).

In 1913, when the first phase of the country’s most intensive industrialization was underway, the situation changed radically. The contribution of wood fell to 21%, while that of coal rose to 41% (

Bartoletto and Rubio 2008).

WWI represented a new watershed in the Italian energy system, during which coal consumption by the mechanical, steel, and electrical industries rapidly increased. Not only the war but also technological progress brought about important changes in production, and the lack of natural resources such as coal placed an important limitation on economic recovery at the end of WWI.

During the

Ventennio, coal represented the main energy source in the Italian energy balance and was a key factor for the economic and industrial growth. For this reason, major investments were made by the fascist regime to expand coal production, especially on Sardinia Island. However, as shown in

Table 1, despite the efforts to expand Italian coal mines, most consumption, mainly for industrial purposes, was satisfied by coal imports primarily from Great Britain.

Coal net imports from abroad, as shown in

Figure 1, rapidly increased, except during WWII and the 1929 crisis. A major rise in coal imports occurred during the first years of the fascist regime (1922–1929), due to the recovery of the Italian economy and the development of the electrical, mechanical, and steel industries, which are very energy intensive. To reduce the dependency on energy from abroad, the regime was able to expand hydroelectric production, thanks to the abundance of water resources in Italy, mainly in the northern regions. Indeed, hydroelectric production rose from 4380 GWh in 1922 to in 13,420 in 1935 (

Terna 2024, historical data). However, the problem of foreign dependence on coal imports became more serious when the regime lost the support of the US and Great Britain following Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and the introduction of racial laws against Jews. As a reaction, there was a further increase in hydroelectric production, which reached a peak of 19,270 GWh in 1941. Nevertheless, during the years 1914–1945, the quest for energy independence represented a central issue not only for Italy but also for major producers of coal, as the United Kingdom and Germany. The rapid growth of per capita and total energy demand could not be satisfied only with coal, but required the introduction of new energy sources, such as oil, causing a significant change in the geopolitics of energy (

Toprani 2019;

Bartoletto 2020).

Regardless of trade relations with foreign countries and therefore hypothetically considering Italy as an independent system, to cope with the growing need for coal, the country had three possible alternatives for investment: imports from the colonies, opening new mines, and raising the efficiency of the production system.

As regards the first possible intervention, the only Italian colony was Eritrea and, although many expert technicians were sent to carry out surveys and the Italian General Petroleum Company (Azienda Generale Italiana Petroli, AGIP) organized a scientific mission in the hope of finding hydrocarbon deposits that would verify the potential of the controlled territory, these failed and Eritrea ultimately became a demographic and commercial-oriented colony rather than a resource for the energy Italian market (

Gagliardi 2016).

With reference to the possibility of excavating new coal mines, ACal carried out surveys regarding possible new mines both in Friuli, Arsa mine, and in southern Sardinia in Sulcis Iglesiente. With its thousand-year history in the mining sector and based on new surveys, Sulcis Iglesiente received the most attention in this context.

With reference to the efficiency of the production system, during the fascist period, the mining sector was affected by a great innovative spirit. This approach covered all the main factors of the mining sector: technological updates with reference to excavations and connected tools, transport, resolving critical issues such as sanitary problems, low productivity, conflicts between workers and managers, etc. This innovative approach was particularly evident in Sulcis Iglesiente, which became the leading Italian case in the coal sector.

To fully understand its potential, an in-depth study of this case study was required.

4. Sardinia as a Land of Mines

Sardinia Island, geographically located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, has a long history connected to its mining sector and a strategic commercial role (

Ferrai Cocco Ortu 2008). Its geology contains a large variety of subterranean mineral sources—above all, obsidian, nephrite and jadeite, copper, lead, bronze, iron, zinc, silver, and coal—that at first supported manufacturing activities and later the industrial development of the Mediterranean basin. In addition, the construction of naturally protected ports, together with an efficient private railway network (

Sabiu 2007), historically supported the storage and transport of minerals, positioning Sardinia Island at the center of the Mediterranean routes of minerals: In southern Sardinia, the ports of Portixeddu, Buggerru, Cala Domestica, Masua, Nebida, Funtanamare, Carloforte, and Is Canneddas (today le Portovesme) and several mine-owned railways (

Sanna 2012) collectively attest to the island’s integrated industrial system (

Colavitti and Usai 2011).

Based on these premises, during the

Ventennio, Sardinia was supposed to play a crucial role in production and the commercialization of mining sources thanks both to the solid mining character of the island’s economy and because coal was the main energy source in the industrial sector. Sardinian coal resources had a primary role, overall, as an effect of the establishment, in 1935, of the Italian Coal Company (ACaI), whose main objective was the nationalization of Italian coal mines through the merger of the old managers and the acquisition of the urban heritage of the mining towns as well. In this new scenario, the approach adopted by the fascist regime was to exploit the coal sector to the maximum in the name of the economic Autarky, introduced to face the international sanctions imposed after the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 (

De Toma 1940;

Lkahlaoui 2021).

In the period of 1933–1938, as reported in

Table 2, many changes occurred in the Sulcis mining basin, both at a management level and regarding the opening of new coal mines. With reference to the first aspect, the concession for the management of the historical Bacu Abis mine, which expired in 1933, was assigned to a new administrative body: the Sardinian Coal Company. This new body, from 1938 on, managed the new mines of Seruci and Nuraxi Figus, and as an effect of additional tests carried out by ACaI, one more mine was opened in 1937: the Serbariu coal mine (

Figure 2).

Based on this new scenario, in Sulcis Iglesiente, a city–countryside dualism emerged. In fact, the decision to invest massively in the coal production sector occurred when the so-called

bonifica integrale (Italian rural reclamation) was already underway (

Dau Novelli 2007;

Novello 2012). Enhancement and recovery of the land, with its social, economic, cultural, and sanitary issues (

Murru 2006;

Tognotti 2018), began in parallel with the strengthening of actions connected with the new coal-oriented insular approach: transport networks, urban and technological development, training, and migratory processes.

The foundation of the city of Carbonia—Royal Law n. 2189-5/11/1937—reflects this dual approach. Its foundation reclaimed the territory and strengthened rural activities to support local citizens, while its functional connection with the Serbariu mine brought about the social and economic progress connected to the Italian energy transition; this took the form not only of energy for industry but also new services for people, such as comfortable houses, a theatre, an indoor market, etc. (

Peghin and Sanna 2009).

The fascist propaganda (

Adinolfi 2012) stressed both of these aspects, above all using the case study of Serbariu mine and the city of Carbonia to support the idea that, thanks to the internal production of coal, the advancement of knowledge in all the sectors connected to mines, and the efficiency of supposed archetype of mine cities, the Italian system was freed from what Mussolini defined as “foreign bondage” (

Bertilorenzi 2020).

The opening of Serbariu mine and the foundation of Carbonia had a great impact on internal production, the efficiency of the mining sector during the fascist period, and several Sardinian social (

Corner 2002) and economic issues. Serbariu coal mine constantly increased its production during the fascist period, which passed from 450,000 tons in 1938 to 500,000 in 1940 (

Table 3).

With reference to the city mine of Carbonia, this was at the center of several social, economic, and urban strategic plans. As regards the first point, the city, with its comfortable housing and its cutting-edge public services, had a motivational role in the creation of a new class of workers that was strategic to the objectives of the regime (

Mussolini 1936) (

Figure 3). As for the second point, the city itself was intended to be the celebration of Italy’s pretended success in pursuing its energy autonomy goals based on fascist values and technological advancement (

Garroni 2010). With reference to the last point, Carbonia was an archetype of the new urban architecture according to the rational style (

Rifkind 2012), interpreted according to the fascist approach to the organization of public and private spaces (

Peghin and Sanna 2009).

Given these premises, it is not surprising that fascist propaganda used the mine and the city to spread the image of a victorious and avant-garde Italy in propaganda (

Figure 3). Mussolini, the Italian leader during fascism, was personally involved in both the projects, and images and video from these events were at the center of an effective communication campaign managed by the Istituto Luce (

Istituto Luce 2024), the oldest public institution dedicated to the diffusion of cinema for educational and informational purposes in the world, founded by fascism in 1924 (

Argentieri 1979), and in the press as well (

Figure 4).

The focus points of the communication strategy were the industrialization of a poor and depopulated territory with effects on employment rates, immigration, and infrastructures and the role that the new mine played in the Italian energy market.

With reference to the first aspect, it is undeniable that the development of the Sardinian coal mining system and the construction of Carbonia had significant effects on Sardinian unemployment rates and on the diffusion of the urban lifestyle but, on the other hand, new social issues connected to safety and sanitation were introduced. This aspect, however, was well hidden by fascist propaganda on the proclaimed efficiency, mechanism, and modernism and with the liturgies of regime. These were emphasized, for example, during the celebration of the laying of the first stone of the new

littoria tower on 9 June 1937 and the inauguration of the city on 18 December 1938 (

Peghin and Sanna 2009). On those occasions, the celebrations were used to motivate miners coming from agricultural work, to encourage new migration of miners from the mainland, and to offer the whole of Italy the image of a country capable of self-sustaining from an energy point of view, rather than, for instance, underlining the architectural value of a new tower.

But was all this emphasis based on solid elements? Did those inaugurations reflect a real scenario where thanks to the innovative approach to the development of the Sardinian mining sector, Italy would be able to sustain the energy transition autonomously?

To uncover the truth behind the communication of fascist propaganda on this issue, further investigation is required of the real contribution of the Sardinian coal mining system to meeting the internal demand for coal and the real innovative capacity of the Italian mining system.

5. Ideas from Abroad

The mining sector has historically been influenced by technological and management advancements. The Sardinian mining system has always been very dynamic in this respect and great efforts have been made to disseminate updates from abroad. The “news” section published periodically in the reports of the Sardinian Mining Association (AMS) served this purpose in the period between 1897 and 2009 (

Associazione Mineraria Sarda (AMS) 2024). But what were the topics considered priority and on which this constant updating was focused? And above all, did this flow of information undergo any changes during the fascist period, a phase in which the regime supported Italian autonomy in all productive sectors?

In total, 821 reports (

resoconti) from the ASM were analyzed (

Figure 5d), covering the period between the start of fascism in 1924 and the opening of the Serbariu mine in 1937 (note that years 1930, 1931, 1933 were not included because the series was not complete). Since the final goal was to study the technological contamination regarding the coal sector during this period, information from the paragraph “news from abroad” (

notizie dall’estero) was the focus. However, since in the mining sector, many updates can be transversal and can concern common issues, during the first phase, the research classified all reports regardless of the type of mine to which they referred. Information from the reports was classified in 13 fields in an Excel table: Country, Scenario, Studies, Commerce, Trend, Mineral, Total, Logistic, Technology, Machinery, Critical, Sanity, and Mine. “Country” indicates the country where the reported new comes from, “Scenario” refers to the economic context at a comparative level, “Studies” refers to the illustration of technical and scientific studies, experiments, and advancements, “Commerce” indicates that commercial relationships are include in the report, “Trend” refers to the inclusion of data about production and market trends, “Mineral” indicates the sector of cultivation, “Total” indicates the presence in the report of data regarding the amount of total or per capita production, “Distribution” refers to information connected to the logistics of the mine sector: ports, railways, stockage, deposits, etc., “Technology” indicates that the technology adopted for excavations is illustrated, “Machinery” refers to new tools adopted for the treatment of raw materials, “Critical” includes a great variety of problems and illustrates solutions introduced at an experimental level regarding mine workers, competitors, management, etc., “Sanity” indicates occupational diseases and fatal accidents among mine workers, and “Mine” indicates that the type of mine is described: open air, galleries, pools, etc.

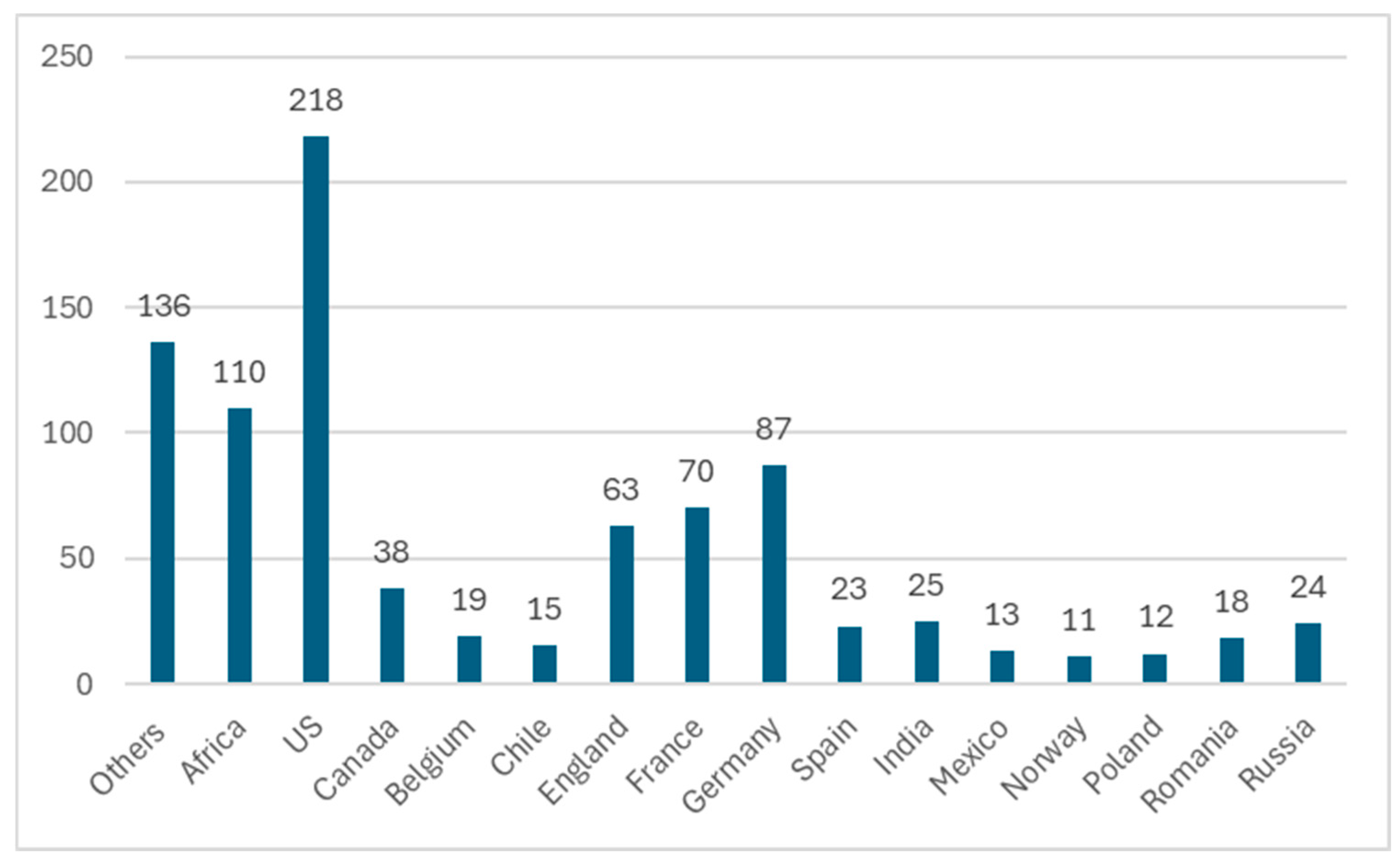

In the analysis, data were organized in two groups: the first introduced the general scenario, Country and Mineral, and the second detailed the contents of the reports, covering all the remaining fields. Data regarding the field “Country” were analyzed by adopting a quantitative approach based on the total amount (

Figure 6), data from the field “Mineral” were classified for years and detailed (

Table 4), and other data were analyzed and the most significant issues discussed.

With reference to the analysis carried out, since several reports were from different geographical areas, mostly at a comparative level, based on 821 records, we compiled a total of 892 case studies from 74 different countries. Africa and Australia were considered countries for two reasons: first, because their case studies were mostly reported like that; and second, because very often they were recorded as “colonies from” (African colonies sometimes were also recorded as

negrolandia, the least polite Italian version for “black land”). The most commonly recurring countries are illustrated in

Figure 6; they are Africa, Belgium, Canada, Australia, Chile, France, Germany, India, England, Mexico, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Spain, the US, and others (countries reported less than 10 times, with a total of 136 case studies). The reports offered a very global and transversal picture. Data referred to colonies, emerging countries, alleys and competitors, leaders and new entries in the mine market, etc. The data showed a very interesting international scenario: the Sardinian mining system was not isolated from the international debate as emerged from fascist propaganda. Data from the US, representing 24% of the total, Germany (10%), England (7%), and France (8%) showed how best practices from western countries were taken into consideration, and data from Africa, representing the 12% of the total, demonstrated how the Sardinian mining system monitored emerging competitors in the extractive sector. The group of “others”, representing 15% of the total, contained data from Mexico to New Zealand, from Japan to Peru, from Australia to Colombia, and from Portugal to Venezuela. The data collected focused much more on technological and managerial innovations than on existing diplomatic and commercial relations. This is a very interesting circumstance because it provides a vision of the regime, as regards technological updating in the driving sectors of the economy, as not influenced by other relational dynamics. Another interesting element is that the reports offer an overview of the connections between western empires—England, Holland, France, Portugal, and Belgium—and mineral resource supplies from their colonies, an aspect that is particularly evident in the period just before the invasion of Eritrea by Italy in 1935.

With reference to the minerals extracted from the mines, the analysis focused on those connected to energetic sources. Four energy sources were found in the records: coal, oil, gas, and bitumen. Data are summarized in

Table 4. The most interesting element to note is that while Italy was on the way toward energy transition from wood to coal and stressing the potential of the Sardinian coal mining system, information about the delay of this operation was already widespread. Moreover, reports from 1926 focus on the global transition from coal to oil, new perspectives on emerging producers (the US, Venezuela, Colombia, Iran, and Iraq), and connected technological innovations.

Data regarding the remaining fields—Scenario, Studies, Commerce, Trend, Mineral, Total, Logistic, Technology, Machinery, Critical, Sanity, and Mine—are summarized in

Table 5.

As for the “Scenario” field, the reports contain data and information on the positioning of the various forms of production in the reference market, the use of local labor and context studies for the colonies, comparative studies between producing countries and their development systems, studies on competitors, changes in supply and procurement countries, and variations in the prices of international metal and fuel exchanges. New scenarios are underlined: in a report in 1928, “China’s exit from the Middle Ages” and the country’s entry into the international market were noted, and in 1932, the ratio between miners and total workers in Belgium, a mine-based country, was 1:10.

With reference to the “Studies” field, new methods for managing various critical issues are reported: new types of probes and mills, new excavation and survey techniques (as well as seismic and magnetic systems), and new systems for optimizing yields in the extraction of metals, their refining and grinding, and the separation of processing waste. Particular attention is paid to innovations related to the prevention of typical critical issues related to mining: cooling, use of safe lamps, safer explosives, ski lifts. The relationship between fuels and the mining world is underlined several times: in 1924, alternative power supplies were discussed, and in 1925, the topic of using combustion waste gases to fuel metal production was introduced. In 1926, the topic of reusing production waste was introduced, which became a recurring theme in the following years, also with an eye to the sustainability of production and transformation processes (1927). In 1926, it was reported that the US was investing substantially in research and how the development of the sector was linked to training in the colonies, like the case of India in 1927. Maximum attention was paid to the new uses of mining products, both metals and fuels, with particular attention to the extraction of oil from coal (England in 1927) and petrol from shale (Canada in 1929). From 1932 onwards, particular attention was paid to the automotive sector, both concerning the metals needed in production and the fueling of engines.

The fields “Commerce”, “Trend”, and “Total” focus on single case studies and offer an overview of the global scenario connected to the mining sector. With “Commerce”, commercial relationships among producers and users and bilateral agreements are listed. With “Trend”, the focus is on the production trend and usually refers to a given production sector. With “Total”, numerical data regarding the per capita production, single mines, or given production sectors are listed, sometimes also at a comparative level.

“Logistic” collects information regarding all the phases following production: from transport inside the mine factory, like the experiment carried out in 1927 in Lorena (France) with the adoption of internal electric transport in the area, to all infrastructures that transported production outputs to the destination both at a national and an international scale. In this list, mine warehouses, like those from Canada in 1927, private and public railways, roads and trucks, port and ships, airports, and connected facilities are also included. In 1926, the Senna and Reno rivers were focused on, and connections with the sea ports were reported. The development strategies implemented in this sector, such as the design of the Polish railway corridor to the Baltic to support German coal mines in 1928, also provided a glimpse of future scenarios. Methods for reducing distribution costs were also illustrated, such as England’s use of empty grain cargoes from Canada in 1929 to ship coal. Alongside coal cargoes, new oil fuels gradually began to be discussed, both in terms of storage tanks in oil-producing countries, such as those built in Guyana in 1929, and in port reception facilities such as those in Antwerp (Germany), described in 1932. New pipelines were reported in Germany in 1928 for the transport of gas and in 1932 for oil in the US. Major infrastructures were also reported, such as the Panama Canal in 1929 for the US, and the Suez Canal for the Egyptian and Mediterranean mining sector in 1934. Major roads, such as the one connecting North and South America, still had an important role in 1932 and were strategic for transport in the US, even if in Katanga (Africa), in the same year, much emphasis was placed on the role of the new railway. Innovations in the river logistics sector also received attention, such as the raising systems adopted in 1934 in Germany and the new channels to reach the emerging port of Oder in Poland in 1936). Great attention was likewise paid to emerging countries and new fuels: studies were undertaken in 1934 on the oil pipeline to connect Iraq and the Mediterranean, of which the first section up to Tripoli was inaugurated that year, on that of Palestrina, connected to the new port, and on US ones. There was talk of integrated transport, canals–ports in Antwerp (1934), railways–ports in Congo (1934), oil pipelines–ships in Iraq (1934), and Nile River–trucks in Sudan (1935), along with depots for the interchange railways–ports in England (1936). Several national scenarios were studied as well: in the US, for example, railway transport of mineral products was reported to cover 51% of the entire service in 1935. In Alaska, for the first time in 1936, air transport was introduced in the mining sector for the transport of expensive machinery, perishable goods, and specialized technicians.

The “Technology” field concerns the approach to the excavation of minerals, such as open air or galleries and their treatments, also at an experimental level. “Machinery” regards equipment adopted during the various phases of production, while “Critical” refers to several critical issues experienced during production: problems related to the management of the workforce, management methods, exogenous problems, such as variations in the market price or critical issues related to the climate that affect activity, and effects of production on the surrounding environment. The critical issues were illustrated analytically, and, above all, the reports illustrated the solutions adopted for their management. Particularly interesting are the issues related to the environmental sustainability of the processes, such as, for example, the effects of mining activity on crops in the US in 1927, the release of poisonous acids in France in 1928, and the salinification of water basins in the US in 1928; it was also noted how, in 1929, the excavations of a mine in China were interrupted due to archaeological finds. Many reports address the issue of workers’ strikes and their repercussions on the raw material markets: it is noted that the strike that occurred in 1928 in England caused an increase in imports from Germany due to the interruption of production. The criticality of the cohabitation of workers of various ethnic groups in Australia (1934) is also highlighted. Additionally, there is room for industrial espionage: in 1929, the case of English spies in Russian coal mines in Russia and the dangers connected to such practices is illustrated. Cases of smuggling are also reported, such as that of Malaysia in 1936. Many cases are linked to the nationalization of production, to producer consortia, and to the methods of granting licenses to private individuals; the effects of such maneuvers on production are also detailed, as are the effects of import duties imposed by some countries, such as in the US in 1932, and state subsidies in Belgium and Spain in 1934. Many reports are linked to safety management: collapses and fires with victims among miners are reported, as well as the prevention activities put in place for their prevention. In 1928, the opening of an experimental station for the study of safety measures was reported in England, and in 1932, the introduction of a regulation for mine safety in 1930 was reported. The per capita productivity of workers is one of the recurring topics, as is the relationship between mechanization and employment (England 1932). Already, in 1922, reports speak of the training sector at the comparative level, citing the cases of Australia, where a school was closed due to the cessation of the gold mining to which it was connected, and in England, where, as an example of investment in technical dissemination, the doubling of investments in the distribution of newspapers and magazines in the sector among technicians is cited. Reference is also made to the experience of French mines that experimented with home teaching in industrial centers with women as fundamental figures, both in caring for the family within the household context (hygiene, childcare, horticulture) and as direct workers in the industrial production process. From 1932 onwards, critical issues related to the need for specialized labor in Germany began to be reported, and the focus was on the training of specialized technicians.

Finally, “Sanity” refers to recurrent professional illness, while “Mine” is the field that was checked when the report included a description of the mine.