1. Introduction

Technology in its most basic form is a material means to achieve a particular, and presumably desired, end. From this point of view, the automobile is just another embodiment of a millennia-long process of transport improvements aimed at moving from one point to another with the least effort expended by man or beast, and as quickly and efficiently as possible. In this sense, the earliest known prototype of a car, a working steam-powered vehicle developed by a French inventor in 1769, was simply one step in an ongoing chain that ultimately led to the petrol-powered machines of the late 19th century, and continuing into the more advanced cars of today (

Eckermann 2001, p. 14).

This narrative accords with a traditional view that technical invention is neutral with respect to society as whole, but few hold to this simple position anymore. In fact, technology arises from, and simultaneously affects, the society from which it springs (

Ceruzzi 2005;

Kranzberg 1986). In the case of major innovations, like the automobile, these social impacts are profound. Yet these are rarely planned for in advance, and the vast uncontrolled socio-technical experiments that follow generally deliver mixed social results that are usually impossible to undo, and difficult to adjust, after the fact.

Thus, a key question is the degree to which technology is a product of society and vice versa. A related question is how the differing cross-causalities between the two change both technological and social forms. This paper considers these questions by briefly summarising the literature on technology and society, and then conducting a structured examination of the social dimensions of the rolling-out and utilisation of the automobile in the United States since the early 20th century, starting with the early days of auto adoption steeped largely (but not exclusively) in technological idealism, moving through an age of car-ascendancy peaking in the 1950s and 1960s (with the birth of a literal “car culture”), and into the present day of automobile dependency and changes in auto technology, with their varying societal implications that are still largely unexplored.

This paper begins with a review of the literature considering the interaction between technology and society; describes the paper’s methodology, which consists of a structured narrative examination of the diffusion of the automobile in the United States from its earliest days in the very late 19th century through to the present, using both qualitative and quantitative data, to assess the changing relationship between the car and its broader American social, economic and political context; breaks down the history into seven thematic “phases”; and offers some conclusions about the future of the car and society more broadly, as informed by its American historical trajectory.

2. Literature Review: Technology and Society and Technology in Society

The usage of the term “technology” in English was, interestingly, not common before the 20th century, and its meaning has shifted over time. Broadly speaking, technology can encompass specific tools, knowledge, ideas, and techniques and/or refer to their application to practical purposes (

Salomon 1984). Technical progress in these terms is relatively easy to understand, and one technical advance does tend to lead to others, typically resulting to increasing efficiencies in narrow but important practical dimensions such as productivity.

There is, however, little apparent necessary relationship between the advancement of technology and human social development, at least on a consistent basis. The vast literature on this relationship has conflicting findings that vary according to context.

den Hond and Moser (

2023) offer a useful tripartite template of analytical paradigms to frame the relevant issues around technology and society. The first is a functionalist model that views technology in purely instrumental terms. In its more extreme version, technology is seen as purely “neutral” socially, divorced from social arrangements, merely representing a collective choice of a technical apparatus to solve particular technical problems. Most variants of this approach do not go quite this far, recognising that society can shape technological forms as they progress, but still asserting that technology nonetheless emerges autonomously as a way of better meeting human material needs.

A more recent school of thought can be labelled under a “values” rubric, in which technology is posited as socially non-neutral, a means of achieving social ends, ranging from the narrow objectives of certain powerful interest groups to encompassing broader ideological or intellectual goals pursued by a larger social/political/economic nexus. Although often couched in terms of technical efficacy, and often with real technical advance involved, technology in this construct is seen as fully bound up with the social order, both as cause and effect. “Social constructivism” is one variant of this approach, holding that technology is thoroughly and inextricably a product of the society from which it springs, and all its forms and motivations are “constructed” out of that wellspring.

A third approach can be labelled as “relational”, seeing agency as distributed throughout a social and technical system, across both human and non-human actors, with the end results, both technologically and socially, arising from an ongoing interaction between these different agencies. Obviously, the primary agency initially rests with the human being. But as systems grow more complex and human beings become more enmeshed in them, the machines and material relationships become more directive and constraining on human choices, effectively having a sort of agency of their own. Indeed, Homo sapiens has been asserted as being a technological being subject to being dominated by their own technologies, different from most other species.

3. Methodological Approach

These approaches are not completely mutually exclusive, and arguably, one paradigm can apply more in some times and places than others. The relative importance of social versus technical forces underlying technological progression will be explored here by examining a very broad historical case study, namely, the diffusion of the automobile in the United States of America from its earliest days in the very late 19th century until the present. This analysis does not involve new or primary historical research, but uses a temporally and thematically structured historical review of the adoption of the auto in one of the most technophiliac societies of the time, as a way of drawing out the relative importance of technical versus social development in a particular context.

The data examined are both quantitative (e.g., car registrations) and qualitative (e.g., changes in social norms and institutions). The analysis will be primarily narrative in nature. A particular focus is on the evolution of “socio-technical systems” (described in the next section), with trends in the adoption and diffusion of the automobile in the US being assessed with respect to changes in policies, production and distribution mechanisms, public attitudes, urban and transport planning, and land use patterns.

4. Phase 1: 1890–1915: The Rise of the American Automobile “System”

The term “socio-technical systems” has become a term of art in current technology and society studies to capture the fact that modern technology goes beyond mere technical relationships. Thomas Edison, for example, designed his invention of the light bulb as an integral part of the electricity generation and distribution network that he himself was so instrumental in designing and implementing. Edison’s main goal was to generate electricity, and then transmit and sell it to consumers. To do this, he aimed to keep the consumer costs of his electrical gadgets as low as possible. With the light bulb, the competition was with existing gas systems and gas lighting. This context crucially affected the design of the light bulb, which was not technically the most efficient, but rather was the most economically competitive one, because it could undercut gas light on price. Here, the embedded economics of institutions of the larger engineering system shaped technical considerations rather fundamentally. This is an example of how a technological system is never merely technical, but always has integral economic, organisational, political, and cultural aspects (

MacKenzie and Wajcman 1999, pp. 16–20).

The American car arose out of its own socio-technical system, one that was, in fact, initially closely related to the electrical grid. Indeed, by 1900, 4192 cars were manufactured in the US, 1575 of which were equipped with electric motors. Even more were run by steam (1681), with only 936 possessing an internal combustion engine (

Lowson 1998, p. 17). It would be this last technology that would win out, however, and its predominance was based only partly on technical factors. While petrol engines had longer ranges, making them more economical for long trips, electric vehicles (EVs) were very competitive within growing and increasingly dense cities. A bifurcated market for both technologies seemed possible for a time (

Sovacool 2009, p. 416).

However, the American mobilisation for World War 1 generated a need for producing masses of vehicles for the war effort, and the US government decided that the flexibility of petrol machines was preferable for military trucks and other vehicles. This boost in demand tipped an already precarious balance towards petrol. After the war’s end, a slew of demobilised and trained petrol car and truck operators slotted back into the peacetime domestic economy, with skills for driving petrol—not electric—cars. This degraded the already declining market position of EVs (

Sovacool 2009, p. 417). This progression towards petrol-powered cars has many other nuances, but this particular institutional “happenstance” is indicative of technical progression coming out a complex array of social, economic, and institutional factors.

Regardless of its power source, the car did offer a number of genuine answers to specific technical problems for Americans, most particularly speed, flexibility, individual mobility, carrying capacity, and range. Intercity railroads and urban streetcars were the dominant alternative modes as the automobile began its rise at the turn of the 20th century. Urban streetcars dominated travel within cities, reaching their peak usage of 14.5 billion passengers carried in 1917 (

Foster 1979, p. 368). Travel between cities was dominated by heavy rail. These “common carriage” modes had obvious advantages in efficiencies across load capacity, delivering riders to their destinations at a much lower average cost per passenger/mile, reaping significant economies of scale across extensive built-out rail networks. They were thus generally more affordable than automobile travel, particularly within metropolitan areas. Railroads were also especially good for long-distance heavy bulk freight carriage, a market they dominated through much of the century.

But against this, streetcars and railroads ran on fixed networks, requiring passengers to adapt their travel to the carrier’s requirements. The personal, individualised carriage of the automobile was not limited in this way, and in less urban areas where transit was sparse or non-existent, the car was the only viable mechanised alternative, even with relatively primitive rural roads being a limiting factor for ease of travel. Trains, for example, were limited to around 30,000 miles of nation-wide track in 1920. But motorists could ride on almost three million miles of passable dirt roads, and they could choose their own routes and timing and—especially important in the

zeitgeist of the US—act as their own “pioneers” through “frontier” territories. Rural communities, in particular, as distinct from transit-rich cities, were often completely cut off from the larger society, typically distant from rail stations, and with farm households often unable to afford the high fares or gain much from the limited service offered to them. The coming of the car was thus seen as an unalloyed godsend for rural America, which, in many ways, it was. Even in cities, the streetcar “traction trusts” and the rapacious railway companies earned bad names by seeking to squeeze passengers and local governments (which contracted out the operating franchises) with high fares in return for less-than-optimal service. The car simultaneously helped break a preceding era of social isolation and economic underdevelopment in the American countryside and excessive market power of transport suppliers in the cities (

Sovacool 2009, pp. 420–22).

On the supply side, mass production, as perfected (though not invented) by Henry Ford and his assembly line, turned the car from a luxury item for a few enthusiasts to a machine affordable by the middle classes. There were a mere 8000 registered vehicles in 1900; but after this elitist phase, American motor vehicle registrations rose to almost 500,000 in 1910 (

Foster 1979, p. 368). Much of this increase in passenger car registrations occurred between 1907 and 1910, tripling from 140,000 to 458,000, and then further rising to 1.2 million in 1913 and to 3.4 million in 1916 (

McCarthy 2001, p. 61). There was thus a confluence between the genuine technical needs that the car met, and the ability of an industrial system to provide vehicles

en masse.

These shifting dynamics can be seen in the other point-to-point transport technology that the car (and rail modes) replaced: the horse. Horses did not need smooth roads—in fact, did not need roads at all—and were already well entrenched in the countryside. They had also already been adapted to use in the growing cities, as hansom cabs, delivery vehicles, and the predecessor to streetcars, the omnibus (from which the term bus was later derived), which were large horse-drawn carriages, first driven along roads, and later, on rails, that became predominant by the mid-19th century in both European and US cities. But horses were much slower in speed, a definite disadvantage in a transport arena that emphasised fast travel more and more. And buying and maintaining a horse was expensive, generally out of reach for the middle-class household, much less the working-class one. Mechanisation ultimately drove out horse-led mass transit and urban horse movements generally, as streetcar and then car travel fell in average price (

Morris 2007).

Meanwhile, industrialisation itself had completely altered the socio-technical landscape in which horses moved. Industrialisation worked on economies of scale and density, a dynamic that led to ever larger and denser cities both to live and to work in. Horses, by contrast, had what economists would refer to as declining economies across both dimensions. That is, their operating costs rose as density and urban scale increased. A collective crisis of manure disposal in cities mounted as the number of horses in cities grew, added to by a growing crisis in disposal of horse carcasses, horses having lifespans of only around 3 to 5 years at best in difficult city environments (

Sovacool 2009, p. 413). The invention of the automobile fortuitously “solved” these problems, which themselves had arisen out of the very economic processes that brought them about in the first place.

By 1915, automobiles in the US were part of an increasingly integrated social and economic system; they were, at first, a product of that system and then slowly moved to becoming its centre, with each new system increment focused on the car rather than its alternatives. The car’s genuine technical advantages were further augmented by the changes in the characteristics of a larger socioeconomic nexus that emphasised technical performance, implicitly subjugating social dimensions to technological change. This nexus narrowed and focused the form of the car, from electric to petrol and then to standardised models that sacrificed individuality for the lowest possible sticker price, Ford’s Model T being an exemplar.

5. Phase 2: 1915–1925: The Bias Towards Technological Progress and Panacea

Technical innovations always have their boosters and enthusiasts, and the car was no exception. The first major American press coverage of the car was of a Paris–Bordeaux auto race in 1895, an event explicitly staged as a car promotion. Many other major races followed, designed with the sole purpose of celebrating the speed and efficiency of the new invention. A tight and hyper-positive car community arose, consisting of inventors, innovators, and committed early adopters who became influential proponents of the rapid adoption and diffusion of this new technology, publicised by an adoring press that was usually fed information by the proponents themselves. Edison called the car the “coming wonder”, and his employee at the time, Henry Ford, would branch out in little more than a decade towards his own mass production of affordable autos for the masses who adopted it in their millions (

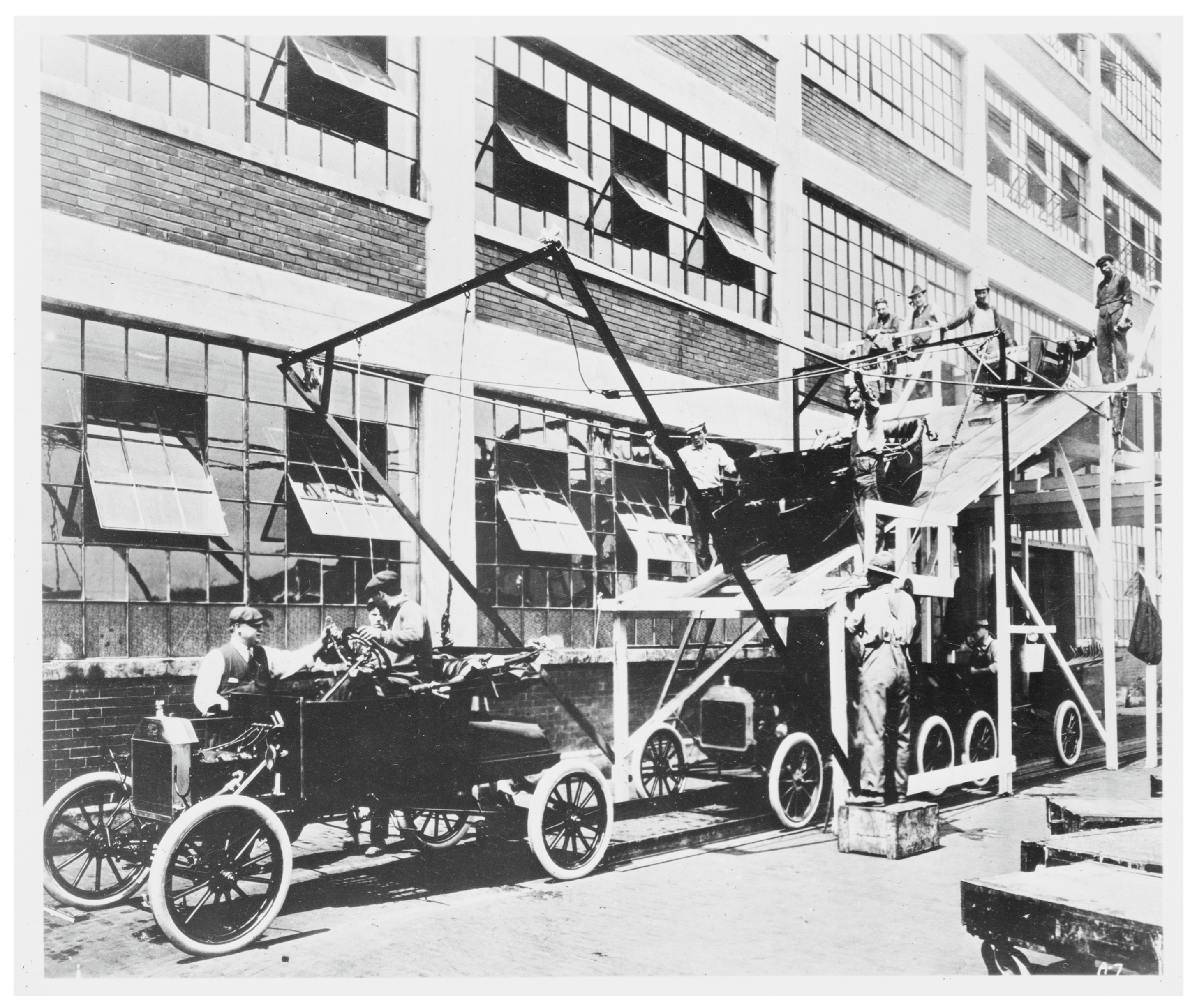

McCarthy 2001, p. 47) (See

Figure 1).

However, even in these early days, problems associated with automobiles were well known, including their greater demand on scarce road and street space, their noise, and the dangers that their high speed posed to non-motorised travellers, especially (

Foster 1979, p. 381). Despite the limited knowledge and foresight of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was possible to see the car as something other than an unhindered social good or technological panacea, if one cared to look for its dark side.

Those that did care to included the wild and woolly—and fragmented—film industry of the 1900s and 1910s. The first film companies were small entrepreneurial outfits, making short reels at cheap prices, aiming to appeal to their largely working-class city audiences who were most directly affected by the social and economic tensions of the day. The effect of the automobile on the urban fabric (rural situations were much less well represented in film generally) was of particular interest (

Sloan 1988, pp. 32–36). “Chase” scenes, involving all modes but focusing on cars, were an early comedic staple of the pioneering film comedians Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, among others (

McCaffrey 1964).

Car crashes were an even more dramatic—and popular—filmic focus, and not always presented comedically. The film,

How It Feels to Be Run Over, produced in 1900, showed the present dangers of the automobile and was followed up by the

Explosion of a Motor Car (1900), as well as

The “?” Motorist (1903), the latter depicting a policeman being carelessly driven down (though, in true movie fashion, he gets right back up to apprehend the perpetrators) (

Cahill 2008, pp. 302–5).

These films were partly voyeuristic, representing the fascination of the public with the new automobile technology. But they also captured the fears and real issues created by cars in cities. These early depictions of car problems rather quickly developed into a genre of urban techno-dystopia movies, such as Fritz Lang’s 1927 Metropolis, which projects out technological and urban trends into an imagined but plausible urban future of shining edifices towering over conditions of social and economic inequality. (Mad Max and Blade Runner are much later, and more gruesome, examples of the genre.)

The societal downsides of the car, especially the dangers they presented to pedestrians on what were still largely unregulated streets, were thus already a concern to the masses at this early age; dread and fear mixed in with fascination and appreciation. The street itself became a battleground between two visions: an older customary one of mixed use with priority given to walkers; and a newer, more technocratic, one that gave priority to the speed of the automobile and designing infrastructure to support it (

Norton 2011).

Indeed, safety was a major and growing issue during this period, reflecting similar and earlier challenges posed by the introduction of the bicycle. It is estimated that over 210,000 Americans were killed in traffic accidents between 1920 and 1929, three to four times more than those killed in the previous decade. In cities, roughly three-quarters of traffic fatalities were pedestrians (

Norton 2007, p. 332). Initially, American case law, judicial opinion, and traffic regulation favoured the traditional rights of walkers, reflecting a similar status quo in Europe. Declining safety due to increased travel speed was already a long-standing policy concern, beginning with bicycles and steam vehicles. In 1865, the United Kingdom government passed a “Red Flag” law limiting the speed of steam-powered “road locomotives” to 2 miles per hour (mph) in towns and 4 mph in the country, requiring them be led by a man on foot carrying a red warning flag in advance. This law was not repealed until 1896. In the US state of Vermont, a similar law was in place until the turn of the century, and Iowa briefly had a law requiring motorists to telephone ahead to warn towns of their arrival. American speed limits became relatively universal, though uneven, by the early 20th century, generally kept to 10 mph in towns, the speed of a trotting horse (

Ladd 2008, pp. 27–28). As cars became more ubiquitous, public opinion was at first heavily in favour of keeping cars in cities slow. A high-water mark was a 1923 referendum held in Cincinnati proposing that mechanical regulators be installed in cars to keep their maximum speed within city limits at 25 mph (

Norton 2007, pp. 338–39).

But, by the end of the 1920s, the locus of responsibility for road safety had decisively shifted against pedestrians in favour of the car, abetted by heavy lobbying and public relations by the car industry. The term “jaywalker” was invented during this time, a jay being a term for a country hayseed out of place in the city, with a jaywalker thus being someone who did not have the requisite urban walking skills. Jaywalking became criminalized, and legal responsibility for accidents moved rather decisively from drivers to pedestrians (

Norton 2007, pp. 343–51). This was very much in keeping not just with industry special interests but a general bias towards urbanity and “modern” “machine age” thinking, the latter term being explicitly invoked in some debates to cast opponents and backwards and against “progress”.

Other concerns were also present at the car’s inception. The gasoline engine had always raised concerns about fuel availability, a nagging issue discussed early on in the car sector’s premier technical magazine,

Horseless Age. Mass production heightened such initial concerns, though improvements in oil refining and discovery of new supplies ultimately made this particular issue recede in importance. Not so easy to dismiss was the gasoline engine’s production of smoke, with automakers concerned about looming public regulation of this legal “nuisance” (the larger health issues surrounding emissions not yet being fully understood) (

McCarthy 2001, p. 54). Although initially obscured by the fact that manure odours were a problem too, there was some understanding that the smell of engine fumes was different and likely more noxious, both subjectively and objectively. These ecological concerns were marginalized, however, especially since pollution was generally accepted as unpleasant but necessary by-product of economic and social modernisation. It would be a few decades before these particular issues came to the forefront.

Overall, this period was a critical inflection point between the pre-car social-economic order and the emerging car-oriented one. Both were solidly industrial and technologically modern eras, sharing a high degree of faith in technology as an instrument of unalloyed “progress”. Just as earlier transport innovations, like rail, brought both benefits and costs, so did the car. And, in both periods, it was the technical benefits that were emphasised over the broader costs in the end. The result, repeated often during the first and second and subsequent industrial revolutions, was that a transition which could have gone in either a more- or less-technically-oriented direction, aligned various social and other forces to leans towards the former (

Gordon 2023, pp. 232–35).

6. Phase 3: 1925–1945: Mass Consumption, Consolidation, and (Brief) Retrenchment

The middle of the 1920s marked an apogee of perceived technical and economic dominance of American enterprise. Mass production—now being referred to as Fordism, in recognition of Henry Ford’s innovations—was entrenched across a whole range of industries, led by automobile producers who encouraged mass consumption of their product and perfected techniques for doing so. Mass marketing and distribution became features of all industries of the time, but carmakers proved especially innovative. The annual auto show, alliances with financial intermediaries to provide easy financing, automobile insurance, comfortable dealer premises with the new concept of a “test drive”: all these were standard selling techniques by the 1920s, which, combined with continually falling vehicle prices, created a well-oiled and growing American car market (

Sovacool 2009, pp. 418–19).

There was also clever and effective promotional positioning, a sort of private sector social engineering that defined the car as a social status symbol that put mechanism over corporeality (i.e., the motor versus the horse) and individual carriage over common carriage (i.e., the car as individual travel mode on demand versus the fixed schedules and crowded carriages of the train), making it more than just a means of travel but a “lifestyle” and a sign of prestige (

Sachs 1992). Technological advantage was now enhanced with a posited social advantage.

All this tied into an age of systems thinking and technocratic planning. The idea that all major social problems were technical in nature, requiring systemic technical solutions, had a pedigree going back to the middle of the 19th century in Europe, when industrialisation was posing many novel problems of urban growth, national economic productivity, and public health and education management, to name a few. Government was seen as a flywheel that coordinated social and technical forces to achieve technically, and hence socially, optimal ends (

Gordon 2023, pp. 170–73).

In the early 20th century, the so-called Progressive movement in the US emerged as a reformist impulse developed in response to the challenges that rapid economic and technological change posed to social and political stability in that country. American Progressives were proponents of the idea that social issues—all issues, in fact—could and should be addressed with rational, scientific, and technical methods. As individuals, Progressives were mostly drawn from urban and/or upper-class elites. Largely identified with the Republican Party, they were opposed to the Democratic Party machines that dominated most US cities. These machines had heavy working-class and immigrant support, and were much more purely political in their approach to social problems, often corrupt in practice, but offering a patronage-based social contract with the urban masses, providing municipal jobs and services in return for regular voting majorities during election time (

McGerr 2005).

The automobile upended urban policy priorities, shifting them from politics of individual and group bargaining to a nominally professional and expert management of urban systems that were highly technical in orientation. Urban planning was a new emerging field during this time, as was, obviously, highway engineering, both being dominated by educated elites with technical predilections, and thus tinged with Progressive political thinking. The immediate challenge of the urban car was increasingly framed as an issue of managing demand on scarce road space by competing users. The political struggle for primacy having been lost by pedestrians, the safety challenges posed by fast vehicles interacting with slow pedestrians was now presented as a technical rather than social problem by road engineers, with engineering fixes favoured (

Barrett and Rose 1999, p. 413).

Yet, mass urban car travel had conflicting effects. It clogged urban downtowns on the one hand, while accelerating the movement of people to outlying areas on the other, a phenomenon that soon became known as suburbanisation. Entrenched downtown business interests saw both of these developments as threatening, and were now faced with new urban periphery real estate development enterprises that were oppositional and becoming increasingly powerful politically. Greater numbers of voters were now also living in the new suburbs. Urban business interests came together with the relatively new cadres of highway engineers and urban planners to devise a technical solution to congestion that split the difference between these two power bases, explicitly giving primacy to accommodating the auto: grade- and traffic-separated freeways devoting more urban space and mobility to the car. The aim was to speed car travel while making it safer for pedestrians, a position technically neutral on whether cities should stay centralised or dispersed, though, in practice, encouraging the latter (

Brown 2006, pp. 14–16).

Safety in a coarse sense was indeed improved by these measures, since pedestrians were removed entirely from areas where cars travelled the fastest. But congestion proved to be a vexing problem that was not so easily solved. Suburbanisation was increased, not decreased, by this relatively simplistic fix, and this actually required more road building and more car driving. The shape of the urban social and spatial fabric and human scale and community were things left to sort themselves out as they adapted to the auto-centric technical systems that were validated and increasingly implemented on a wide scale (

Foster 1979, pp. 385–86).

There were some dissenters in the urban planning field that wanted to inhibit the car and give preference to the pedestrian on urban streets, following older practices. But these were greatly outnumbered, hindered in their influence by hostility from established interests, since road engineering solutions benefited downtown and urban fringe interests alike with plenty of economic growth to go around, something that was threatened if the car were impeded. Additionally, since cars were now becoming a true mass instrument of travel, any policy option that hampered them was seen as being against the desires of the general populace (

Foster 1979). Views that divorced modern social and political problems from technological advance, and instead saw technology as a wonderful panacea that would sort everything out, became deeply entrenched, at least with respect to cars and cities, and to buck this trend suggested a resistance to inevitable change that was naive at best, and refractory at worst (

Sovacool 2009, p. 421).

Thus, as the automobile became a mass phenomenon, urban planning that emphasised urban amenity and public space became an anachronism. There were simply too many vehicles crowding into too little street space to be accommodated by grand leisurely parkways, and there were increasing numbers of cars that needed to be parked somewhere as well, squeezing into public parks and other “useless” urban amenities. The rise of auto-driven suburbanisation required further investments in the roads that were now taking up space in ex-urban fringes. Besides which, car owners were now a growing consumer and interest group in their own right, whose interests had to be contended with and addressed (

Foster 1979, pp. 376–78).

Meanwhile the highway engineers, already biased towards technical means, with the primary aim of moving traffic faster, developed new data and new models that were very compelling when compared against the older heuristic narratives of the turn-of-the-century city planning (

Foster 1979, pp. 369–70;

Barrett and Rose 1999, pp. 410–12). By the 1930s, urban planning and traffic planning had largely converged into the contours and concepts still with us today: origin–destination pairs, levels of service, and highway capacity—all of which implicitly were about cars taking primacy over the human and social dimensions of city (and, increasingly, suburban) life (

Barrett and Rose 1999, p. 414).

Certainly, the car offered clear technical improvements in comparison to existing transport means of the time, and had some social advantages besides, not least more individual mobility, increased land development opportunities, more choice of affordable housing, and the breaking down of rural isolation. These real advantages of the car were widely diffused though advances in production technology that lowered vehicle prices, making its purchase by individuals more compelling than ever.

But the equally clear and immediate problems of the car were seen in very biased ways that focused on technical issues, favouring narrow technical solutions that, by definition, but implicitly, required widespread adaptation of human society to the automobile, ignoring the possibility of any negative social consequence from this adaptation (apart from the artistic imagination that continued to create dystopian visions extrapolating from such possibilities).

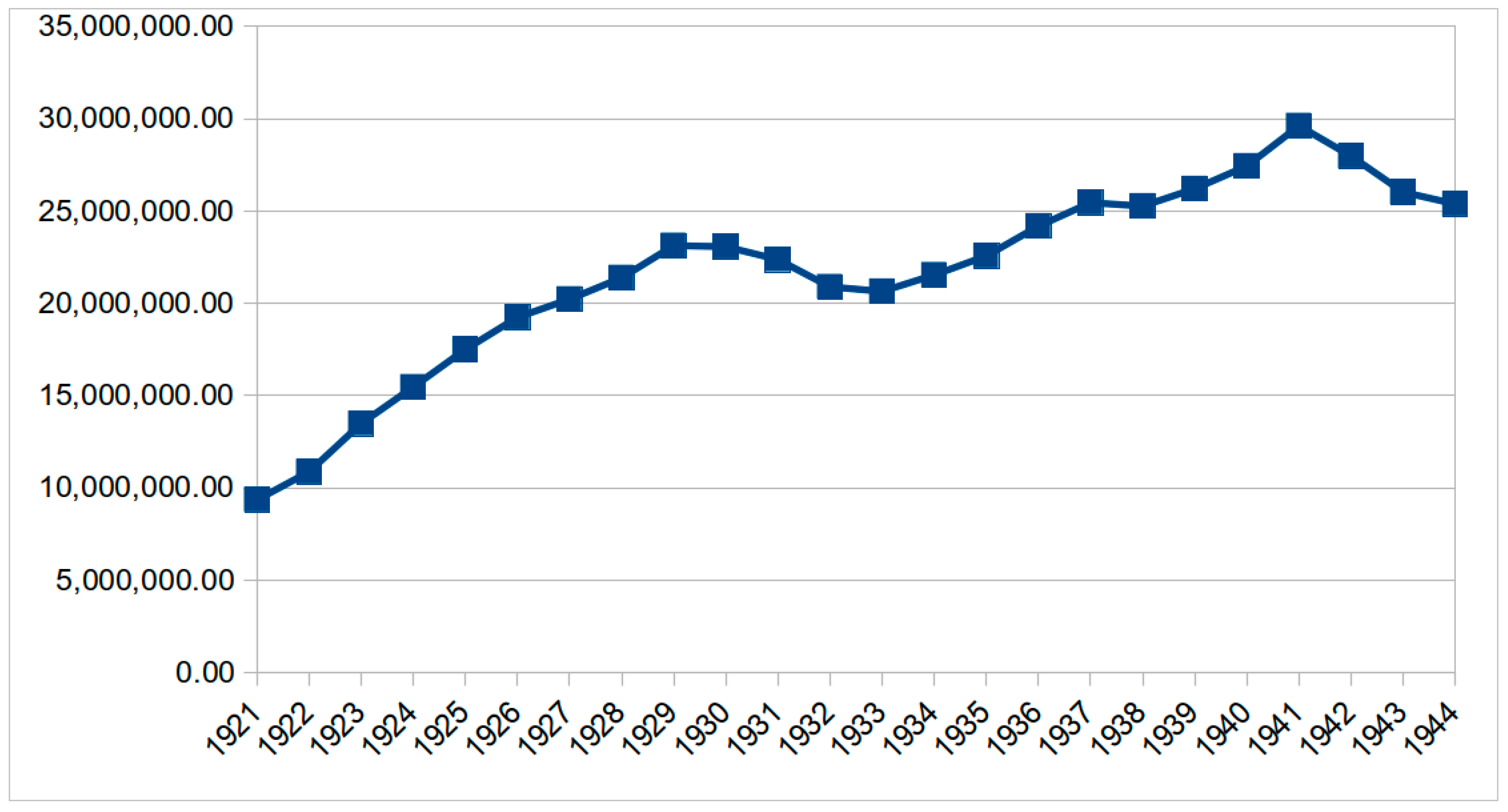

By the 1940s, car-based development was entrenched both intellectually and economically in America. Urban and transport planning was centred around the car, and public preferences were supportive of it. This was particularly striking against the background of the Great Depression, and then wartime rationing and government controls during World War 2, which put pressure on both transit and auto manufacturers, but with transit being the ultimate loser and cars the ultimate winner. In 1929, electric railways carried 14.4 billion passengers, falling to 9.9 billion in 1932. Auto sales fell proportionally even further, from a peak of 4.5 million in 1929 to only 1.1 million in 1932, and auto registrations fell from 23.1 million to 20.9 million over the same period. But driving rates continued to be high, mostly in used vehicles rather than new ones (See

Figure 2). And auto sales recovered after 1932 while transit ridership did not. By 1940, trolley passengers declined to 8.3 billion. Buses did take up some of the slack, but overall total public transit patronage went from just under 17 billion riders in 1929 to 13.1 billion in 1940. By 1940, auto sales had almost recovered their 1929 levels, with 3.7 million units sold, while total registrations were just above 1929 levels (

Foster 1979, p. 383). Transit (and intercity trains) did have temporary surges during the war, as petrol and rubber rationing kept cars in their garages. But this would peter out immediately after war’s end.

7. Phase 4: 1945–1965: Social Planning Based on the Automobile and “Car Cultures”

After World War 2, American government policy shifted completely to very strong and unequivocal advocacy of the automobile over other transport alternatives. Once more, war played a pivotal role, with the US Congress, in 1944, approving

$500 million per year in highway building and authorising (but not appropriating funds for) an Interstate Highway System. The privations of the depression and war had temporarily crimped the growth of American automobile usage and production, but it came back with a vengeance in peacetime, as masses of demobilised troops flocked to the suburbs and started their nuclear families. Auto registrations skyrocketed, and 209,000 miles of new road were added between 1946 and 1950 (though total highway mileage actually fell as older roads were decommissioned) (

Rose 2003, p. 216).

The seismic movement in American road building came with the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which established the Interstate Highway System and the federal highway financing mechanisms that, in a fundamental way, remain in place in the US today. The key compromise was the idea of a broadly based financing scheme tied to highway usage, namely a tax on automobile fuel—the “gas tax”, as it became colloquially known—together with the creation of a dedicated trust fund to ensure that the revenues raised would go back into roads (

Rose 2003;

Weingroff 1996).

This trust fund not only made the infrastructure finance burden almost invisible to car drivers, it also reduced the burden to truckers sufficiently to get their buy-in to the legislation, with a trade between their tax-increased operating costs in return for an ongoing public pledge to fund a growing highway network. The creation of a trust fund itself, although, in actuality, just an accounting fiction, nonetheless created a credible policy commitment against which future promises could be leveraged. Additional cost-shared federal financing for new urban roads that would normally be a local responsibility also brought urban governments on board with what was going to be primarily a suburban and rural network expansion (

Rose 2003). Social problems, especially declining downtowns and urban poverty, continued to be seen as technical problems that could be solved by easier highway access to and through city centres, a “solution” that simultaneously promised to eliminate costly congestion and “slum” neighbourhoods.

The post-war boom in car usage, road building, suburbanisation, and urban “renewal” is a well-known tale not to be repeated in detail here (

Blas 2010;

Dunn 2010;

Seiler 2009). But a few points are salient. Even by 1956, automobile and car-dependent development was not yet completely entrenched. Railroads and urban transit were in decline, as were urban cores, but there was still potential to balance car-based development with existing older residential, commercial, and transport forms. “Car dependency” was growing, but not yet completely pervasive. The die was not yet fully cast; the Rubicon not completely crossed.

However, nobody with real power was interested in possibilities other than car-oriented ones. Technical planning and development was well and truly the accepted paradigm by the mid-20th century, and the policy and institutional changes of the 1950s and 1960s merely accelerated those trends. The Cold War was on, and, once more, war planning and national defence emphasised the supposedly strategic benefits and outcomes of a particular technology (the gasoline engine car) and the infrastructure required to facilitate it. Not by accident was the other name for the Federal Aid Act the “National Interstate and Defense Highway Act”. Longer-term and more diffuse social costs of transport and infrastructure alternatives were uncertain and seemed to pale against such “strategic” advantage. The suburbs were now the mecca for the nuclear family, something that highways and cars facilitated the creation and expansion of, in turn requiring further dependence on the cars and roads, in a virtuous or vicious circle, depending on your point of view (

Florida and Feldman 1988). The “iron triangles” of real estate developers, federal aid housing programs, and local governments following federal grant money combined with developer imperatives became a self-propelling dynamic, aided by an urban and road planning profession that was now wholeheartedly based on the needs of the automobile (

Checkoway 1980).

This was also an era when the “car culture” was well and truly born and blossoming (

Flink 1975,

1988). It was not just that the car had become a normal household item, though that was part of it. There were 49 million registered passenger cars in 1950, jumping to 75 million by 1960, a 53% rise over the decade (

Auer et al. 2016, p. 2). By comparison, the US population in 1950 was 159.8 million, growing only by 19% to a 1960 population of 179.3 million. Mass production and mass consumption were in close sync, and the auto was a big beneficiary.

However, car consumption, like most material relations, was, by this point, also closely bound up with aesthetic, emotional, and sensory relationships to driving, which in turn affected life patterns of sociability, habitation, and work (

Sheller 2004, p. 222). The car was inseparable from the road, which was inseparable from the gas pump, drive-in movie theatre, and suburban home and shopping mall. American films and songs prominently featured the auto and life “on the road”, mirroring the ubiquity of cars in personal and collective life more generally (

Flink 1988, pp. 161–64). This was quite a contrast to the popular culture of the early 20th century, in which cars were generally depicted as dangerous instigators of random accidents and social disruption. Cars were not only needed, they were celebrated as well, both collectively and individually.

8. Phase 5: 1965–1990: Questioning the Car

Cracks did appear in this edifice, becoming particularly evident by the middle of the 1960s. There were a number of dimensions to this. Not least was a flattening of what had been a strong trend in sales growth for American car manufacturers, especially in the first half of the 1950s, when, between 1951 and 1955, sales of American cars in the US rose from 5.16 million units to 7.47 million units, an almost 45% increase in four years. But then sales fell, with 1961 levels being close to those of 1953. There was a strong overall recovery in in the 1960s and into the 1980s. But the trend was choppy; strong linear upward growth was no longer to be expected, replaced by volatile ups -and downs and, increasingly, foreign competition, both at home and abroad. (See

Table 1).

This created something of a crisis in the American automotive industry, which accelerated model and line changes beginning in the 1950s, strongly breaking from the industry’s past of standardised products, produced cheaply, as exemplified by the Ford Model T of the early assembly line era, which was initially the only model the Ford Motor company offered, and which originally came only in the colour black. Now manufacturers were introducing new features annually, largely cosmetic, in a constant bid to stimulate consumer interest and renew a sense of novelty, however confected that sense might be. This established a pattern that continued on into the following decades, and it did have some of the desired stimulative effects. But growth was not as consistent as before, and the retooling and marketing expenses involved in constant model and feature tweaks were considerable (

Offer 1998). In one sense, this was just another typical example of a “mature” industry dealing with saturated demand. But the car was not just a product, but an icon of American culture and dominance. The relative decline in American model car sales represented a deeper and more general fall to most American minds.

The remodelling craze brought to light the long-standing and serious problem of auto safety. This initially had been primarily a problem of cars hitting pedestrians. With walkers now suitably tamed and sidelined, car-on-car crashes became the predominant phenomenon. And it turned out that cars were still very dangerous, ironically made more so by the many redesign elements, such as pointed grilles, that automakers were pushing out to entice buyers towards their product. Traffic fatalities on American roads averaged around 50,000 a year through the 1960s, with many more injuries on top of that, by the time consumer advocate Ralph Nader published his 1965 expose entitled

Unsafe at Any Speed, which detailed the car industry’s wanton disregard for driver and passenger well-being. Auto accidents, as have been noted, were recognised as an issue right from the car’s inception. But crashes had been seen as “chance” events, “caused” by driver (and passenger) error and misbehaviour, to be addressed by punishment of offenders on the one hand, and better design of roads on the other. Nader’s book, and the subsequent uproar it caused, brought in both government safety regulation and a new interest in safe vehicle design by manufacturers who had previously mostly focused on passenger comfort and car performance. For example, although airbags had been invented in 1951, they were not installed in any vehicle until 1973 and were not regular features until the 1990s (

Hakkert and Gitelman 2014, pp. 139–40).

The politically rebellious spirit of the 1960s brought in new political strains, and popular challenges against expert and other authority. The most notorious example of a successful overthrow of an auto-based city paradigm took place in New York City, when Greenwich Village residents successfully opposed and reversed Robert Moses’s plan to put an expressway through Washington Square, this defeat leading to the fall of Moses from power and inspiring further successful efforts elsewhere in New York and in other cities to stop federally funded urban renewal transport projects from displacing existing communities (

Scheper 2008). This was a time of the birth of what could be called a new, neighbourhood-scaled city planning movement, championed by one of the leaders of the revolt against Moses, Jane Jacobs. She championed renewed versions of some older ideas about walkable city spaces with human-scaled community and amenities built in and maintained, rejecting mechanistic, engineering-based frameworks built around the car (

Jacobs [1961] 1993). It should be noted, though, that these developments were driven mainly by an inner-city elite. The movement was led mostly by people who did not drive at all, or at least lived in urban core areas where they did not need to. The broader working and middle classes remained more devoted to the automobile than ever, and needed to be, since most livelihoods and lifestyle depended upon it.

More broadly impactful was the “energy crisis” of the 1970s and the end of permanently cheap oil (and cheap gasoline and diesel), as well as the rise of competitive foreign auto manufacturers. These presented challenges to the American car industry and the position of the auto in society more generally. Cars got smaller and more fuel-efficient while also getting more expensive to drive. Environmentalism took hold as a full-blown societal concern, with the car seen as a major eco-disrupter. Yet, urban and suburban development had locked in place a need for cars which now was seen as something of a burden rather than an unequivocal marker of freedom and status. This first energy crisis did ease, but cars in America had lost some of their lustre by the beginning of the 1990s.

9. Phase 6: 1990–2020: An Evolving Car Stasis

The end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 appeared to bring the possibility of a rethinking of systems, economic and otherwise. Conceivably, this rethinking might extend to the auto. By this time, American primacy in carmaking was clearly a thing of the past. Between 1990 and 2023, passenger car sales by American carmakers in America plummeted from 9.3 million to 3.12 million units (

Table 1). The iconic carmaker Chrysler required a government “bailout” to survive in 1979, while General Motors, the nation’s largest auto manufacturer—and, Chrysler, once again—required government money to continue operating in 2009 (

Huemer 2013).

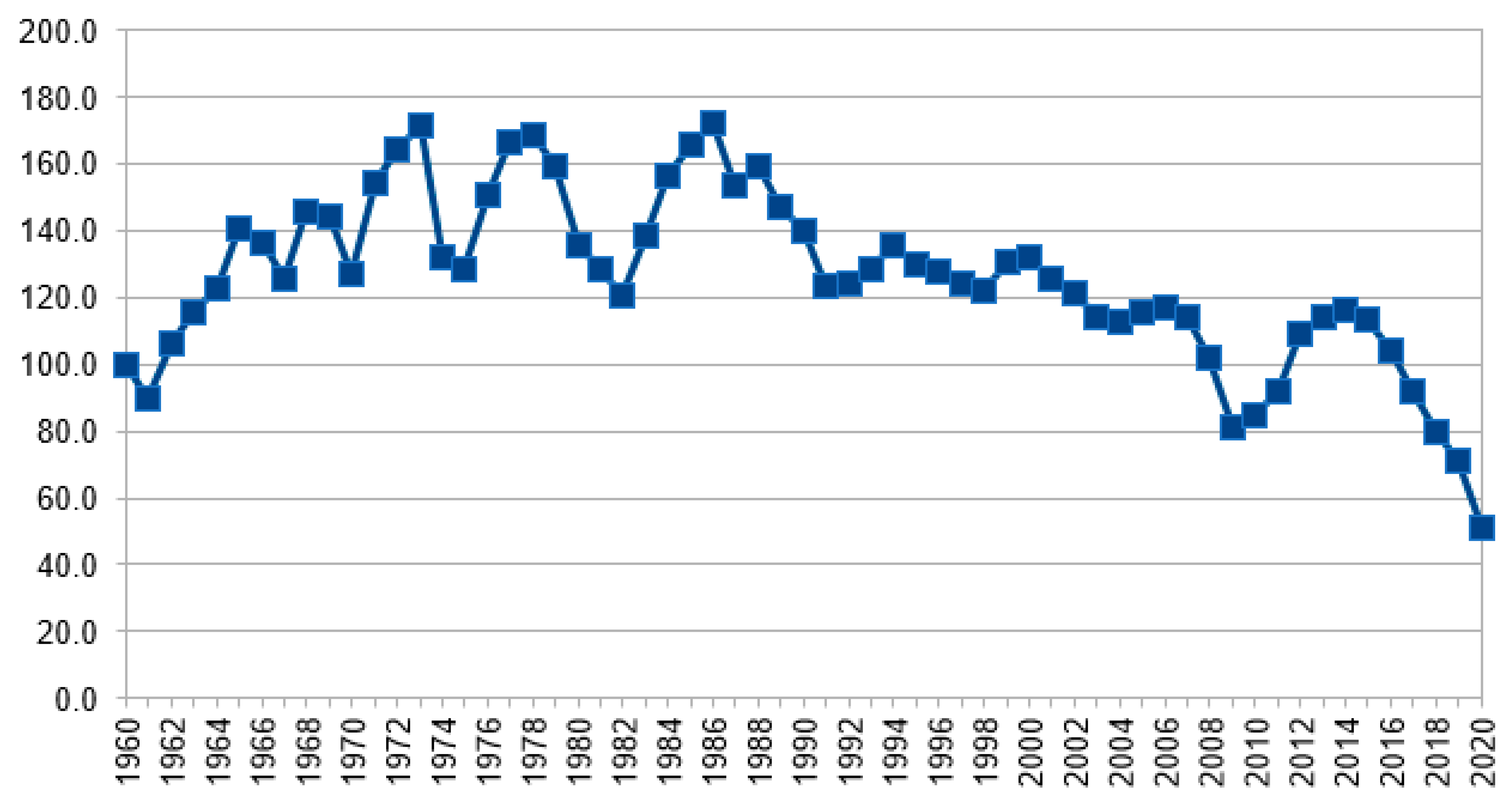

These particular incidents were, to be sure, in the context of two severe recessions. But American car registrations were also falling, overall, from their peak. Using a base year of 1960, with the baseline set at 100, registrations rose from this level, with more volatility than before, to 171.1 in 1973, exceeding this peak slightly in 1986 (172.0), but then falling rather steadily from there. The index was at 140.2 in 1990, falling to 132.4 by 2000, then down to 85.0 in 2010, then down to 51.3 in 2020, representing a nearly 50% relative decline over 60 years. (See

Figure 3).

At the same time, shifting change in tastes became evident, especially amongst younger people. Urban mass transit in the US made a relatively small but significant comeback (up until the COVID-19 pandemic, considered in the next section), and urban “infill” and Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) became accepted “progressive” principles for redeveloping existing urban cores (

Hess and Lombardi 2004). “Smart Growth” became the professional planning template for new development, both inside and outside the urban core (

Handy 2005). This rubric encompasses a set of policies that includes limiting outward extension of new development using urban growth boundaries; raising residential densities in both new-growth areas and existing neighbourhoods; preserving green open space while making land uses more pedestrian-friendly to minimise of the use of cars on short trips; and emphasising public transit usage (

Downs 2005, pp. 367–68).

Planning changes such as these have only partially penetrated professional and policy practice, and their popularity at the grass roots has been mainly with the young. Gen-X, Gen-Y, and Millennials, in particular, are typically more environmentally conscious than older generations and are also more oriented towards urban core amenities, and thus more prone to living in walkable cores and close to niche storefronts and cafes. Individuals within these demographics were not quite so quick to adopt cars or car-based living. As a result, by the 2010s, some were referring to the era of “peak car” usage, noting an apparently declining trend in car usage not just in the US but across all developed countries (

Metz 2013).

10. Phase 7: 2020 to the Near Future: A Mature Industry

The demise of the car has been foreshadowed by a number of crises during its history: the Great Depression, World War 2, the political turmoil of the 1960s, the energy crisis of the 1970s, and the challenge of climate change. Changing attitudes about cities and driving, renewed concerns about automobile safety, the diversification of the global auto manufacturing base, and the economic and political rise of the global “South” are other trends that have periodically raised the possibility that car-ascendancy might be over, or at least slowing down.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2022/3. Travel of all sorts on all modes collapsed. Lock-downs restricted work, social activity, and most service activity to the home. Digital communication replaced face-to-face contact. If anything was going to seismically shift the car and its role in the greater socio-technical system, this seemed to be it.

Yet, somewhat similarly to the 1930s and 1940s, it was transit that suffered most, in the US and much of the rest of the world, with car usage mainly rolling along, so to speak. Rail and bus ridership has recovered significantly from the 40% to 80% drops it suffered during 2020–21. But it has not yet returned to its pre-COVID growth trajectory, and, presently, it is unclear when it will, especially since tram and bus rides are perceived to be less safe with respect to communicable disease transmission than cars (

Wilbur et al. 2023). During the pandemic, private car travel was the only alternative to common carriage of all sorts, thus reinforcing its use by those who continued to have access to it after the crisis was over, and making such access more attractive to those who did not have it. The younger generation, now untethered from the office like everyone else, was discovering the joys of living in the suburbs, or not being near a city at all, reversing some of the pre-pandemic infatuation with inner-city living and transit-travelling. While it is still early to make definitive predictions, from an economic and technical point of view, COVID-19 showed just how resilient—or embedded—or both—the car still is.

To be sure, patterns of auto production and consumption have altered significantly from earlier times. American automaker output has remained relatively small in comparison to production by non-American producers, with China and other “Global South” countries becoming significant producers in their own right. On the consumption side, overall car sales and usage has largely stabilised in the “developed” world, to be replaced by growth in the “developing” world. Between 2015 and 2020, the number of passenger cars in use across the world rose from 949.2 million to 1180.7 million, an average annual growth rate of 4%. Positive growth occurred in most nations, with stagnation in a very few markets, like Japan. Interestingly it was in the US where car usage actually fell, from 122.3 million to 116.3 million units, an annual decline of 1% (

OICA 2024).

Indeed, the car can be seen in conventional product cycle terms as an invention that is still diffusing, but in a mature market, and thus moving from highly saturated areas of the world to less-saturated ones.

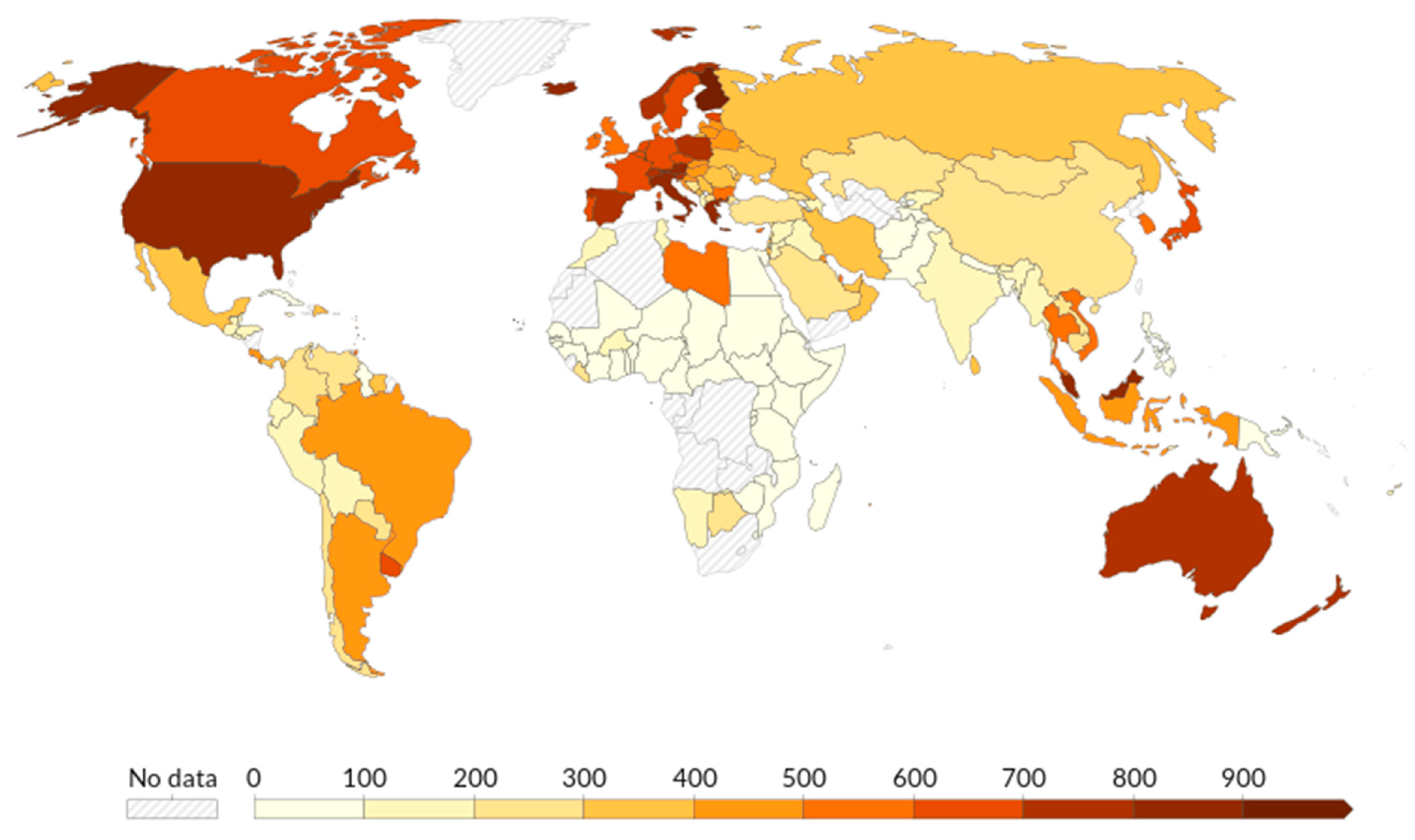

Figure 4 shows the number of registered vehicles per 1000 people in 2017. The US is one of only a handful of countries in Europe, North America, and Australasia that have the highest number of registered vehicles per capita in the world. Many South American and Eurasian nations have medium levels of per capita car ownership. Africa and the Subcontinent contain the bulk of countries with low per capita car usage. It is to these areas that auto adoption is now moving.

11. An Overall Assessment of the Role of the Car in American Society and American Society in the Car

Returning to the opening discussion of the three models of roles that technology plays in society, the American experience with the automobile can be seen as an example of each playing out in various ways at various times. The US was a country where the technical problems of moving a relatively large population across great amounts of relatively low-density space, combined with the transport needs of rapidly densifying cities, were especially well met by the car, particularly as there was not as much built-out infrastructure based on older technologies such as rail, as was the case in Europe. The role of the auto as a primarily “instrumental” use of technology to meet genuine need is well illustrated by the early and enthusiastic US adoption and diffusion of it, which, in this case, also had many economically productive results.

Even in its initial stages, however, a genuine devotion to technical optimisation took a shape that emphasised mechanical performance first, and human conditioning and social conditions second. For example, the car had immediate and extensive negative safety consequences, which initially were met with government speed limits and community resistance. However, these policies were quickly overridden, with priority soon given to the speed of the car at the sacrifice of pedestrian amenity and freedom of action, followed by thorough re-purposing of urban landscapes to suit the machine, not the human. Car-induced environmental damage was also known early on, but it, too, was put in the back seat, so to speak, before coming to the fore in the 1960s (though this is also typical of the attitudes of earlier industrial society, which did not give much priority to these issues unless there was an immediate crisis that needed to be averted).

Idea-systems can be seen as part of the broader socio-technical systems within which technology and society sit, and this, too, played a significant role. The first half of the 20th century was an age of faith in the idea of “progress”, an Enlightenment-era notion that posits a forward movement of human society driven by increasing knowledge and rationality, especially within the US. Downplayed was another side of Enlightenment thought, in which scientific advance was seen as necessary, but not at the expense, or disruption of, moral rules for regulating society’s members. “Rationality”, it was noted, was not always “reasonable”, and “rational” progress along “scientific” or “technical” lines did not necessarily ensure orderly progress of humanity along lines of higher ideals and principles. “Pure” instrumental technological change models implicitly discard these concerns, assuming that all problems are technological in nature, and technological advance thus solves all social, as well as technical, problems (

Hobsbawm 1994). More recent concepts of “disruptive” technology are, in fact, amoral, positing disruption and change as good by definition, without interrogating the inherent assumptions lying beneath this conclusion.

The uptake of the automobile was thus arguably initially a product largely (though not exclusively) of instrumental need. But broader societal values, the workings of interest groups, ideologies, and evolving and often unconscious material relations between humans and their machines, shaped its adoption, with these non-technical factors soon becoming as, or more, dominant in driving socio-technical evolution. One can thus say that the second (values) and third (relational network) paradigms described in the opening literature review became increasingly operative in the diffusion of the car as it became more thoroughly embedded in most facets of American society.

12. Conclusions: The Future—Civilising the Automobile?

It is important to note that human beings progress organically, not mechanistically, implying that there will always be a tension between technical and individual and collective human progression. The sociologist Norbert Elias studied the way in which automobiles and their systems upended organic human growth and self-regulation. He observed how the car was at least partially de-humanising this process, referring to it explicitly as a “decivilising” process through “technisation”. Even in what can be generally considered to be relatively pure technical aspects, such as road safety, the social dimension is present. Traffic fatality rates thus vary widely across countries and cannot be accounted for solely by technological or policy differences. Humanity still matters (

Elias 1995).

A full return to the city and periphery patterns of the late 19th century, even if economically and technically feasible (which it obviously is not) would not be fully desirable since those old urban spaces had as much dis-amenity for the mass of the population as they did amenity. For all the considerable social damage that untrammelled car adoption and development has done, it did address and ameliorate many emerging problems of industrial society, especially in the US. Once, only relatively privileged elites could afford houses of their own in the city or out in the country, and transport inaccessibility was a real problem outside many urban cores. Even those masses with transport access were beholden to the often rapacious operators of tram and railway companies. Meanwhile, pedestrians had to navigate chaotic and dirty unregulated and poorly maintained streets, even before the car (and horses could be just as deadly as cars from a pedestrian perspective, even though slower) (

Morris 2007). The car and its associated infrastructure did ameliorate many of these problems objectively.

These changes have required significant human adjustment, as is the case with any innovation. the mere speed of cars does require significant adaptation by human creatures evolved to deal with much slower movements and decisions than are required to be made on automobile networks. Mechanical aids of all sorts, from traffic lights, to signage, to automatic barriers, are needed to minimise casualties and properly manage system traffic flow, and people need to adjust to these accordingly; however, much of this may go against natural human impulses. The cost, though, can be a sort of inner alienation from one’s body, one’s chosen mode of movement, and potentially from many of the human embodied and intuitive pathways of society. And the evolutionary pathway of the car followed in the US (and, to varying degrees, most other countries) was not the only, or even the most optimal, one. Pedestrians, for example, began with the advantage of incumbency during the early stages of cars in cities, but they were soon subordinated to motorised traffic. As car systems grew more intensive and extensive, this subordination became more and more pronounced (

Dant and Martin 2001). This can be a depressing and enervating message, and not one always good for people and their social relations.

The response to auto safety is particularly indicative in this regard. The “human factors” field puts the car (or mechanised systems more generally) first and adapts human beings to it, the very term indicating that human elements are just “factors” in the larger technological system rather than masters of it (

Salvendy 2012). “Human factors” has thus evolved into a socio-technical system approach focused on the totality of human–technology interactions in a functionally performative framework of technical “optimisation” which aims to “improve” either the human operator (e.g., better training), technology (e.g., to fit the machine to the human better), or both, to attain “efficient” and “safe” operation (

Durso et al. 2014). Ultimately, the ideal is to take the human completely out of system decisions and operations, utilising automation more and more, and purportedly error-prone and random human agency less and less (

Auer et al. 2016, p. 31).

Car safety comes out of the broader field of industrial safety, which itself arose as an issue because danger in the workplace reached a scale and scope that increasingly interfered with productivity, imposing significant production costs. Workplace injuries began to be recorded in the 1800s, but the way they were measured was controversial, and the occurrence of industrial accidents did not so much lead to many actual social reforms, but to reconfiguration of shop floors to keep process-flow disruptions to a minimum. Interestingly, legal traditions began to change, with defences against negligence on the basis of accidents being due to “Acts of God” being thrown out by judges more and more, the phrase becoming limited to truly extraordinary and unpredictable events. Implicitly, this was a recognition of a paradigm where “accidents” were actually an operating feature of the system that could be optimised along with everything else (

Loimer and Guarnieri 1996, pp. 102–4).

What is interesting about all this is that while cars have become “safer” in relative terms, with declining accident rates, there is still a very high tolerance for ongoing traffic-related deaths and injuries. The World Health Organisation (WHO) reported in 2023 that almost 1.2 million people died on the world’s roads, the ninth-leading cause of death globally and the leading killer of young people aged 15–29 years. Road crashes also result in between 20 million and 50 million non-fatal injuries annually. This annual toll is roughly equivalent to French battle deaths, and all battle injuries sustained by all combatants, during the entire First World War (

WHO 2023). This toll continues after decades of human factors engineering improvements.

It is also revealing that the future being planned for continues to put automobiles at the centre of mobility. The only purported differences between the current status quo and this future order are vehicle energy source and operational direction. EVs are being pushed as a “decarbonisation” solution, rather ironically putting electricity back in the dominant position it was at the turn of the 20th century transport. Meanwhile, “autonomous” and “driverless” vehicles are being touted as solutions to urban congestion and infrastructure capacity that is already overtopped and underfinanced. A technical bias predominates in this paradigm. Questions such as what effect autonomous vehicles will have on urban space, social fabric, human institutions, and folkways of living and being are being considered mostly after the fact of their introduction, and, in this way, marginalised in transport and urban planning and overall climate change response (

Norton 2021, pp. 130–36).

There are also legitimate questions about how practical and feasible the proposed solutions are from a technical point of view. Autonomous vehicles are always just around the corner, according to their inventors. And yet a fully autonomous open-road system, even on a small scale, is not clearly in the offing even after four or more decades of its pursuit. “Clean” EVs are growing in number. And yet there remain hard questions about how carbon-reducing, on a net basis, these vehicles will be, especially after considering the carbon emissions of electrical generating systems themselves and embedded carbon in infrastructure and other transport support facilities. There is also the obvious point that if cars are part of the current environmental and traffic congestion crisis, is it really plausible that they are also the prime solution (

Norton 2021, pp. 227–33)? The continuing auto-centric and technological model of mobility suggests that larger socio-technical system factors are at work.

Granted, now, many prefer to travel by car than by other modes, and are not particularly bothered by “car-dependency”. A car-centric model of cities and societies is firmly embedded at present, with little prospect for major alteration any time soon. This is not entirely “bad” nor “good”. But the past is also not necessarily the prologue, nor should it be. The US experience with the auto suggests that just letting technological progress rip, and reacting to all its many social impacts after the fact, is not a socially, or even technologically, desirable approach. Explicit attention needs to be given to the question of how to shape and direct a social order that seems most human and most sensible, and brings technological progress in that will equate with and promote social progress. “Smarter” vehicles and systems should not be assumed to be socially intelligent just because the word “smart” is in their title. Human “smarts” need to be dedicated to the human aspects first.

An analogy can be made with the introduction of foreign plants and animals to an ecosystem. Ecologists know well that such introductions have wreaked havoc in the ecosystems they were supposed to benefit, with many unintended and unforeseen consequences. Though these introductions continue (often unintentionally), scientists nonetheless do study the possible impacts in advance more than they once used to, and sometimes attempt to avoid such introductions entirely, or at least adapt them to the greater requirements of nature as they are. Similarly, instead of wholesale introduction of “new” autos, one might first try to “civilise” the untamed car technology and make it fit for and consistent with human society and its social development, and then introduce and develop it in a “civilised” manner, in the sense of according with larger human social needs and desires. At a minimum, social planning for technological introductions can aim to refrain from “uncivilised” or “barbaric” (i.e., socially harmful) uses to avoid doing societal harm—in the case of the car, avoiding “carbarism”—a play on the word “barbarism” (

Gordon 2017).

Yet, it seems that the same broad technological orientation that characterised the earliest diffusion of the car in the US still prevails in its assumptions that new technologies will create a brighter and more progressive society automatically (no pun intended). This orientation had its reasons for being, and its outcomes have been both positive and negative. Yet reliance on mere technical innovation, impressive as it is, will not guarantee such an outcome. If the American automobile experience is any guide, humanity will end up with a more sophisticated and even more machine-based world, with unknown but certainly significant negative societal consequences.