“There Is No Law for Me in England”: An Indian Grocer’s Struggle for Economic and Geographical Space, and Agency in Oxford (1888–1896)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Counter-Colonialism and Reversed Flows of Migration from the Empire

2.1. Strange Death of a Hindoo

From Surij Singh, etc., to Mookhi Singh–Greetings. We are all well here and hope you are the same. We received a letter from you and noted its contents. You say that you will send us some money if we give you all our particulars. I don’t understand what you mean by ‘particulars’. I have written all I could, if you cannot understand how can I help it. You ought to think of your home now your father, uncle and brother are all dead, and you ought to come here for a short time. We look up to you as the head of our family and I consider you as my father–elder brother. Pray write and say what you are doing there. Please send some money if you can. If you haven’t any, write and tell us so plainly. Write and tell us your address. Please date your letters in Hindi. Your last letter reached us on the 12th March. Written from ….. 13th March, Monday.

2.2. Harassment by the Local Community

2.2.1. Assaulting a Man of Colour

2.2.2. 1889, Two Male Youths Throwing Stones at Singh’s Shop

2.2.3. 1890. Singh Accused of Committing Indecent Assault on a Boy

2.2.4. Two Youths Damage Singh’s Shop Window by Throwing Mud

2.2.5. Singh’s Shop Damaged by Two Youths and Then Repeat the Offence

2.2.6. Three Youths Break into Singh’s Shop

2.2.7. 1895. Two Youths Break Singh’s Shop Window

3. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Oxford City Police Force had been formed on 1 January 1869. Oswald Cole was Chief Constable there from 1897 until 1924, when he is reported to have died while sitting at his desk at the Police Station (Rose 1979, p. 9). |

| 2 | For a comprehensive discussion of the Suez Canal, the advantages of travelling via this route, and how it modified migration from India to Britain, see (Boehmer 2015). |

References

- Banerjea, Surendranath. 1893. ‘Bengal Speech 14 January 1893’, in Banerjee, Sukanya. In Becoming Imperial Citizens: Indians in the Late-Victorian Empire. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer, Elleke. 2015. Indian Arrivals 1870–1915—Networks of British Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, Christine. 1971. Victorian Attitudes to Race. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Antoinette. 1998. At the Heart of the Empire: Indians and the Colonial Encounter in Late-Victorian Britain. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Antoinette, and Indrani Ray. 1999. At the Heart of the Empire: Indians and the Colonial Encounter in Late Victorian Britain. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Arup K. 2021. Indians in London—From the Birth of the East India Company to Independent India. New Delhi: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Bankim Chandra. 1954. Baboo. Rachanabali. Calcutta: Shishu Sahitya Sangsad, vol. 2. First published 1894. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, Arunima. 2021. Responses to travelling Indian ayahs in nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain. Journal of Historical Geography 71: 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Arunima. 2023a. ‘Stranded: Indian Travelling Ayahs Negotiating Waiting and repatriation’. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 30: 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Arunima. 2023b. Waiting on Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Christian, Rose McDermott, and David Armstrong. 2018. Protests and Police Abuse: Racial Limits on Perceived Accountability. In Police Abuse in Contemporary Democracies. Edited by Michelle Bonner, Guillermina Seri, Mary Rose Kubal and Michael Kempa. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Michael H. 2004. Counterflows to Colonialism, Indian Travellers and Settlers in Britain 1600–1857. Ranikhet: Permanent Black. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg, Carlo. 1980. The Cheese and the Worms. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwich and Deptford Observer. 1888. ‘Assaulting a Man of Colour’. The Greenwich and Deptford Observer, February 24. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, Daniel J. R. 2020. Monstrous and Indefensible? Newspaper Accounts of Sexual Assaults on Children in Nineteenth-Century England and Wales. In Women’s Criminality in Europe. Edited by Manon van der Heijden, Marion Pluskota and Sanne Muurling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Catherine, and Sonya Rose. 2006. At Home with the Empire—Metropolitan Culture ad Imperial World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Douglas. 1980. Crime and Justice in Eighteenth-and-Nineteenth-Century England. Crime and Justice 2: 48–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchin, Charles. 1718. The Regulator: Or, A Discovery of the Thieves, Thief-Takers, and Locks, Alias Receivers of Stolen Goods in and about the City of London. With the Thief-takers Proclamation. London: T. Warner. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, Sayako. 2019. Family, Caste, and Beyond: The Business History of Salt Merchants in Bengal, c. 1780–1840. In Chinese and Indian Merchants in Modern Asia. Leiden: Brill, pp. 104–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly’s Directory. 1889. Oxford, St. Ebbe’s. London: Kelly. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly’s Directory. 1890. Oxford, St. Ebbe’s. London: Kelly. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly’s Directory. 1894. Oxford, St. Ebbe’s. London: Kelly. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly’s Directory. 1895. Oxford, St. Ebbe’s. London: Kelly. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly’s Directory. 1896. Oxford, St. Ebbe’s. London: Kelly. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore, Jill. 2001. Historians Who Love Too Much: Reflections on Microhistory and Biography. The Journal of American History 88: 129–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List or Manifest of Alien Passengers. 1920. May. Available online: https://ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Magnússon, Sigurdur Gylfi. 2003. ‘The Singularization of History’: Social History and Microhistory within the Postmodern State of Knowledge. Journal of Social History 36: 701–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manekin, Devorah, and Tamar Mitts. 2021. ‘Effective for Whom? Ethnic Identity and Nonviolent Resistance’. American Political Science Review 116: 161–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Claude. 2000. The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750–1947—Traders of Sind from Bhukara to Panama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, Andrew. 2022. Sikhs: A Stateless Nation, a Powerful Cohesive Diaspora and a Mistaken Identity. In Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Post-Brexit Britain: Political and Social Challenges. Edited by Romain Garbaye and Vincent Latour. Revue de civilization britannique contemporaine/Journal of Contemporary British Studies. Perugia: Petruzzi Editore, pp. 135–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, Sumita. 2012. The representation and display of South Asians in Britain (1870–1950). In South Asians and the Shaping of Britain 1870–1950. Edited by Ruvani Ranasinha. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Omissi, David. 1994. The Sepoy and the Raj: The Indian Army, 1860–1940. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1888. ‘To Rent’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, October 13. [Google Scholar]

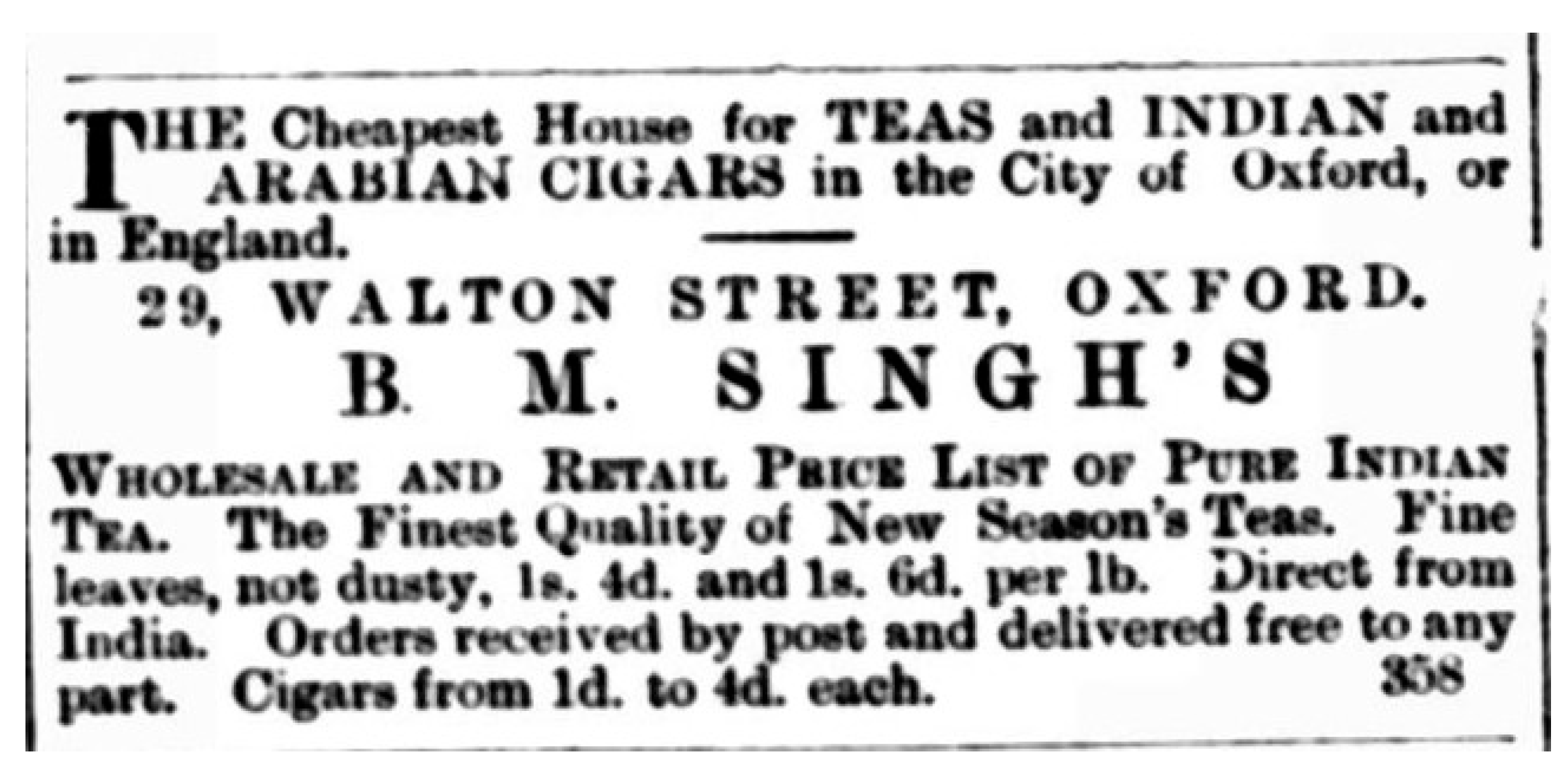

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890a. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, September 13. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890b. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, August 16. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890c. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, August 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890d. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, September 20. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890e. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, August 23. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890f. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, June 28. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890g. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, September 6. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1890h. ‘Serious Charge against a Grocer’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, November 15. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1891. ‘Oxford City Police Court’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, February 7. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1892. ‘Oxford City Police Court’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, October 16. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1896. ‘Death Announcements’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, May 23. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Chronicle. 1916. ‘To Rent’. Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, July 21. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Journal. 1890. ‘Horrible Charge against and Indian’. Oxford Journal, November 15. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1889. ‘Troublesome Boys’. Oxford Times, November 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1890a. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Times, August 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1890b. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Times, July 26. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1890c. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Times, July 5. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1890d. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Times, September 6. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1890e. ‘Trade Announcements’. Oxford Times, August 9. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1891. ‘Obscene Literature’. Oxford Times, September 5. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Times. 1896. ‘Strange Death of a Hindoo in St. Ebbe’s’. Oxford Times, May 23. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfordshire Weekly News. 1892. ‘Oxford City Court—Tuesday’. Oxfordshire Weekly News, November 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfordshire Weekly News. 1893. ‘Juvenile Housebreakers’. Oxfordshire Weekly News, September 27. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfordshire Weekly News. 1895. ‘Alleged Wilful Damage’. Oxfordshire Weekly News, July 31. [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen, Matti. 2001. Clues, Margins, and Monads: The Micro-Macro Link in Historical Research. History and Theory 40: 347–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Police Charge Book. 1890. Oxford City, POL1/1/A14/3. November 10, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Police Court Records. 1889. Oxford City, PS7/A1/22. October 29, 410–11. [Google Scholar]

- Police Court Records. 1890. Oxford City, PS/A1/23. November 11, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Police Court Records. 1891a. Oxford City, PS7/A1/24. September 1, 115–18. [Google Scholar]

- Police Court Records. 1891b. Oxford City, PS7/A1/23. February 6, 374–75. [Google Scholar]

- Police Court Records. 1892. Oxford City, PS7/A1/25. October 21. [Google Scholar]

- Police Court Records. 1895a. Oxford City, PS7/A1/27. July 23. [Google Scholar]

- Police Court Records. 1895b. Oxford City, PS7/A1/27. July 30. [Google Scholar]

- Police Occurrence Book. 1896. POL1/1/A1/31. May 20. [Google Scholar]

- Proclamation. 1858. Proclamation, by the Queen in Council, to the Princes, Chiefs, and People of India. British Library Images. Available online: https://imagesonline.bl.uk/asset/161781/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Ranasinha, Ruvani, ed. 2012. South Asians and the Shaping of Britain 1870–1950. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Regina v. Hicklin. 1868. Law Reports 3: Queen’s Bench Division. London: Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Geoff. 1979. A Pictorial History of the Oxford City Police. Oxford: Oxford Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Salter, Joseph. 1873. The Asiatic in England: Sketches of Sixteen Years’ Works Among Orientals. London: Seeley, Jackson and Halliday. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafi, Mitra. 2010. The Martial Patchwork of Colonial South Asia: Forum Shopping from Britain to Baroda. Law and History Review 28: 979–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, Marika. 2001. Race, empire and education: Teaching racism. Race and Class 42: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Kalsi, Sewa, Ann Marie B. Bahr, and Martin E. Marty. 2005. Religions of the World: Sikhism. Broomall: Chelsea House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtler, Florian. 2012. Britain’s forgotten volunteers: South Asian contributions to the two world wars. In South Asians and the Shaping of Britain 1870–1950. Edited by Ranasinha Ruvani. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Streets, Heather. 2004. Martial Races—The Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture 1857–1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tabili, Laura. 1993. “Keeping the Natives under Control”: Race Segregation and the Domestic Dimensions of Empire 1920–1939. International Labor and Working-Class History 44: 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bicester Herald. 1896. ‘Death Announcements’. The Bicester Herald, Friday. May 29. [Google Scholar]

- The General Register Office. 1896. UK, Death Certificate Mookhi Singh. Oxford: June Quarter, vol. 3a, p. 463. [Google Scholar]

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1890a. England and Wales Criminal Registers 1791–1892, Class Ho 27, Piece 216. p. 391.

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1890b. The UK Calendar of Prisoners 1868–1929, 140 Home Office Calendar of Prisoners, HO 140/123.

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1891a. Census Return 1891. Class: RG12; Piece: 1168; Folio: 36; Page: 6; GSU roll: 6096278. [Google Scholar]

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1891b. Census Returns 1891. Class: RG12; Piece: 1164; Folio: 21; Page: 36; GSU roll: 6096274. [Google Scholar]

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1891c. Census Returns 1891. Class: RG12; Piece: 1168; Folio: 40; Page: 13; GSU roll: 6096278. [Google Scholar]

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1891d. Census Returns 1891. Class: RG12; Piece: 1168; Folio: 78; Page: 5; GSU roll: 6096278. [Google Scholar]

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1891e. Census Returns 1891. Class: RG12; Piece: 1168; Folio: 77; Page: 4; GSU roll: 6096278. [Google Scholar]

- The National Archives (TNA), Kew. 1891f. Census Returns 1891. Class: RG12; Piece: 1168; Folio: 44; Page: 22; GSU roll: 6096278. [Google Scholar]

- Trivellato, Francesca. 2015. Microstoria/Microhistoire/Microhistory. French Politics, Culture & Society 33: 122–34. [Google Scholar]

- Troyna, Barry, and Richard Hatcher. 1992. Racism in Children’s Lives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Venn, John A. 1922–1954. Alumni Cantabrigienses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Visram, Rozina. 2002. Asians in Britain—400 Years of History. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Visram, Rozina. 2015. Ayahs, Lascars and Princes—The Story of Indians in Britain 1700–1947. London: Pluto Press. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 2020. The Distribution of Power Within the Political Community: Class, Status, Party. In Classical and Contemporary Sociological Theory: Text and Readings. Edited by Scott Appelrouth and Laura Desfor Edles. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, Irving B., and Donald K. Freedheim. 2003. Handbook of Psychology. vol. 11, Forensic Psychology. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Woolwich Gazette. 1888. ‘Assaulting a Man of Colour’. The Woolwich Gazette, February 24. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Robert C. 1995. Colonial Desire-Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milne, A. “There Is No Law for Me in England”: An Indian Grocer’s Struggle for Economic and Geographical Space, and Agency in Oxford (1888–1896). Histories 2024, 4, 465-486. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4040024

Milne A. “There Is No Law for Me in England”: An Indian Grocer’s Struggle for Economic and Geographical Space, and Agency in Oxford (1888–1896). Histories. 2024; 4(4):465-486. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4040024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilne, Andrew. 2024. "“There Is No Law for Me in England”: An Indian Grocer’s Struggle for Economic and Geographical Space, and Agency in Oxford (1888–1896)" Histories 4, no. 4: 465-486. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4040024

APA StyleMilne, A. (2024). “There Is No Law for Me in England”: An Indian Grocer’s Struggle for Economic and Geographical Space, and Agency in Oxford (1888–1896). Histories, 4(4), 465-486. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4040024