1. Introduction

The long invisibility of women in history, which Gerda Lerner denounced in a groundbreaking 1975 article entitled

Placing Women in History: Definitions and Challenges (

Lerner 1975), has long been illustrated by the absence of statues representing female historical figures in public space. Evacuated from an androcentric conception of history and memory, women have long been subject to a dual process of invisibilization and disembodiment. Until the beginning of the 20th century, female figures in the public sphere were essentially fictional characters, angels or allegories (of justice, peace, freedom, progress), allegories adorning the female body with accessories whose belonging to the symbolic order reflected the gap with the reality of gender and power relations

1 (

Warner 1885;

Rooney 2021).

Since the 19th century in the United States, the growing presence of women in the social and political arena, coupled with the rewriting of American history begun by feminists, particularly in the 1960s and 70s, have contributed to the creation of new historical and memory frameworks. These frameworks are never distinct and never fixed, with historiography defining and redefining the subjects to be commemorated, and the objects of commemoration constructing in return a collective memory that sheds light on contemporary tensions and issues (

Rooney 2021;

Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie 2019, pp. 2–3). This dynamic is particularly relevant to the analysis of the history and memory of women’s suffrage in the United States. Monuments dedicated to suffragism, in particular, represent privileged sites and invaluable tools for “exploring the fluid interactions between history and memory”. (

Rooney 2019, p. 22) They also highlight the fact that monuments are “not (..) static objects but discursive sites” (

Rooney 2019, p. 22).

At the intersection of memory and feminist studies, this paper seeks to explore the questions raised by the monumental commemoration of suffragism in the United States and, more broadly, of feminism. Among the various possible sites of memory, this article will mainly examine public monuments; one reason for this choice is that monuments are visible public objects that are shaped by multiple negotiations, commemorate the past and warn about the present and future. As Quentin Stevens notes:

A monument reminds. Its location, form, site, design and inscriptions aid the recall of persons, things, events or values. In contemporary English usage, ‘monumental’ means large, important and enduring. Monuments generally honour, and their prominence and durability suits subjects of lasting merit. But the derivation of monument from the Latin verb monere suggests remembrance that serves to admonish or warn people in the present.

(951)

Conventional monuments were criticized in the 20th century for failing to remind or warn, for externalizing the burden of memory and “seal[ing] memory off from awareness altogether” (

Nora 1984) and

Young (

1992), but in recent decades, many monuments have been erected, especially in the United States, in a sort of frenzy that Erika Doss has called “memorial mania” (

Doss 2010).

Suffragism only represents one aspect of feminism (

Cott 1987), and it is probably its easiest dimension to commemorate since all feminists (and even anti-feminists and all citizens generally) now consider women’s suffrage as normal in any democracy. While the commemoration of important suffrage figures is not always consensual, as we shall see, from a contemporary popular perspective, the movement for suffrage is now greatly perceived as monolithic and uniform (although this is historically wrong). By contrast, the issues tackled by the late 20th-century and early 21st-century feminist movements (complete gender equality, sexual harassment, reproductive rights, feminicide, etc.) continue to raise debate and even divide US society (as shown by, for instance, the current debates over abortion). The plurality of feminism is visible not only diachronically, through the successive so-called second, third, and fourth waves

2, but also synchronically, through the diverse and contrasted voices claiming a feminist label that illustrates the absence of a uniform movement. While many women are still reluctant to identify with the “f word” (

Dicker [2008] 2016), a number of pro-life activists belonging to organizations such as Feminists for Life or S. B. Anthony List or some conservative women openly use the word feminism to promote their views (

Schreiber 2008). In addition, in spite of the growing influence of the concept of intersectional feminism, divisions between Black and White feminisms, or the activism of gender critical feminists highlight the difficulties of commemorating a movement for “all women”.

3The very dynamics of monumental commemoration, which seeks to construct and reflect a stable, consensual collective memory, seems complex to reconcile with feminism. As Quentin Stevens recalls: “Traditional monuments are didactic, imparting clear, unified messages through figural representation, explicit textual or graphic reference to people, places or events, allegorical figures, and archetypal symbolic forms” (961). Not only is monumental commemoration problematic with feminism, which, as mentioned above, is multiple. It is also, according to some feminists, inadequate and undesirable because the monument itself partakes of a patriarchal mode, a “bronze patriarchy” (

Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie 2019).

This article will first focus on the conception and reception of two monuments commemorating suffrage (the Portrait Monument, 1921, and the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, 2020), which both shed light on the mechanisms of exclusion and inclusion at work in the process of commemoration and illustrate the intricate interactions between memory and history. A broader perspective will then be adopted, envisioning the contemporary feminist efforts to reject, redefine, or go beyond monumental commemoration and invent new feminist memory frameworks that can be read as countermonuments.

2. Portrait Monument and Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument: A Century of Suffrage Commemoration

As previously noted, the issue of women’s right to vote, considered radical in the 19th century, is now consensual, and the approach of the centennial of the 19th Amendment marked an increased political will to commemorate it nationally: in 2017, Congress voted to create the National Suffrage Centennial Commission for this purpose. The centennial of the 19th Amendment has thus contributed to the creation of numerous statues funded by public or private sources. It is in this context that a statue was erected in memory of the suffragist movement, the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, which was unveiled in Central Park on 26 August 2020. However, to understand the roots and scope of this monument, it is necessary to look at the story of another statue, an earlier one known as the Portrait Monument, a monument dedicated to the pioneers of suffragism shortly after the passage of the 19th Amendment (

Figure 1). This part will highlight how the history of these two statues illustrates the shifting dynamics of exclusion and inclusion that shape historical and commemorative narratives.

The Portrait Monument was presented to Congress in February 1921 by the National Woman’s Party, the suffragist party founded in 1916 by Alice Paul. The monument is quite original in that it depicts several figures: Adelaide Johnson, the sculptress, had, in fact, grouped together in a single work the busts she had sculpted several years earlier and presented at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. Susan B. Anthony dominates the others, however—a reflection of her already worshipped image by the end of the 19th century– and the work appears incomplete, reflecting a desire to symbolize the unfinished nature of the struggle as well as the future generations of women (

Weber 2016, p. 143). But, the statue, which was supposed to stand at the heart of political institutions in the Capitol rotunda, was soon criticized for its ugliness and earned the nickname “3 old ladies in a bathtub”. (

Weber 2016, p. 168).

The day after its inauguration, the Portrait Monument was stored in the basement of the Congress building, in what was then a broom closet, where it remained for 76 years. It is, of course, tempting to see in this decision a symbolic move to evacuate women from the political arena, doubly underlined by the erasure of the inscription at the bottom of the monument, which included the following phrases:

“Men their rights and nothing more, Women their rights and nothing less” (motto of

The Revolution newspaper founded by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (

Stanton et al. 1881–1922), and “Woman, first denied a soul, then called mindless, now arisen declared herself an entity to be reckoned with”.

In the 1990s, in a context of feminist activism concerned with the invisibility of women, a feminist coalition, including the National Woman’s Party, campaigned and succeeded in moving the monument back to its original location between the House of Representatives and the Senate. And on 15 February 2022, New York 12th District Democratic Representative Carolyn Maloney introduced a resolution to restore the above-mentioned inscription (

Marcos 2022).

The return of the Portrait Monument in 1997 was celebrated as a victory, but in the context of growing Black feminism (

Taylor 1998), it also drew criticism from Afro-American associations pointing out its racist nature: indeed, the monument depicts three White middle-class women and glosses over the historically important participation of Black women in the struggle. Criticism focused, in particular, on the fact that Stanton and Anthony, in the aftermath of the Civil War, opposed the passage of the 15th Amendment granting Black men the right to vote. A number of women activists felt cheated and betrayed by their former abolitionist allies who thought it was too early to impose voting rights for Blacks

and women at the same time. In this context, Stanton and Anthony founded an association defending the notion of educated suffrage and did not hesitate to use racist language against Black men considered ignorant and hostile to women’s suffrage Terborg-Penn, (

Dubois 2020).

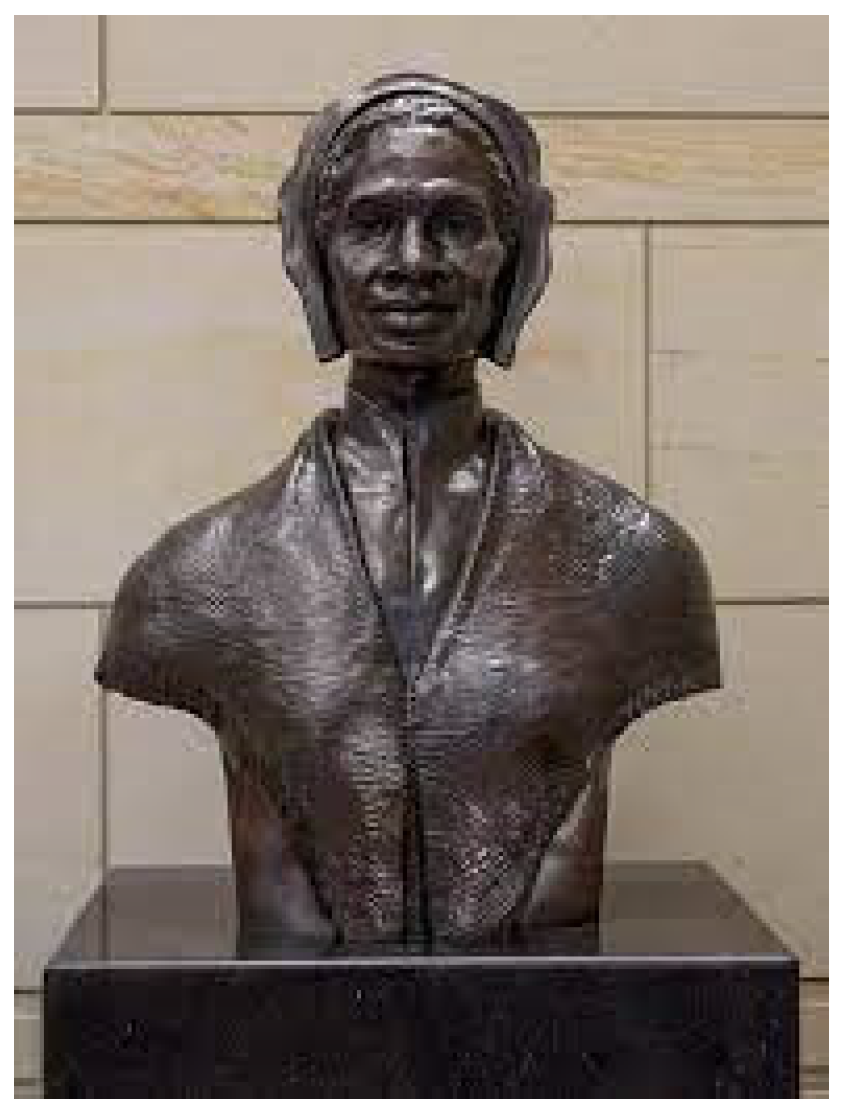

In the 1990s, African-American activists, notably Delores Tucker of the National Congress of Black Women, denounced the monument as whitewashing the history of suffrage and asked Congress to add the figure of Sojourner Truth, a former slave deeply involved in abolitionism and suffragism, to the work. This request was not successful (the problem of modifying an original work without the artist’s consent was put forth), but Congress finally agreed to the addition of a bust of Sojourner Truth to the Capitol, which was inaugurated in 2009 (

Figure 2). This bust was designed by the Black Canadian artist Artis Lane and commissioned by the National Congress of Black Women ((

Architect of the Capitol 2009)

https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/sojourner-truth-bust) (accessed on 30 November 2023).

The debates surrounding the Portrait Monument foreshadow those recently sparked by the project for a statue commemorating the centenary of the 19th Amendment, the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument.

The Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument

The project was initially conceived in 2013 by a group of volunteers chaired by retired lawyer and feminist activist Pam Elam and including Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s great-great-great-granddaughter Coline Jenkins (who was involved in the return of the Portrait Monument in the 1990s). In 2014, the group founded an association, #MonumentalWomen, which raised funds ($1.5 million) for a project called the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Statue Fund. This project had a triple objective: firstly, to produce a statue to commemorate the centenary of the 19th Amendment; secondly, to initiate an educational program aimed at young people and the general public in order to introduce them to the history of women in and of New York; and thirdly, to introduce female historical figures in Central Park for the first time in order to “break the bronze ceiling”. Until very recently, this vast green space in the heart of New York, where many statues can be admired, only featured allegorical female figures or fictional characters such as angels, nymphs, Alice in Wonderland, and Juliet next to Romeo. Therefore, for this association, as for many feminists, Central Park symbolized the clear deficit of historical figures in public space.

Sculptress Meredith Bergmann was chosen from 91 artists to create this work, whose genesis and evolution reflect debates entangling issues of memory, history, race, and class.

Bergmann’s initial project, somewhat presumptuously entitled

Woman Suffrage Movement Monument, (

Figure 3) depicted Anthony and Stanton: Anthony is shown standing in a dominating position, placing her hand on Stanton’s shoulder, a gesture that symbolizes their 50-year collaboration and was inspired by an actual photograph. The statue portrays them at a younger age; as for Stanton, she is shown writing quotes from 22 suffragists on a long parchment rolling down into a ballot box.

The presence of other names on the parchment reflects Monumental Women’s and the artist’s desire not to reduce the movement to these two tutelary figures and to pay tribute to the participation of suffragists of color and from working-class backgrounds: included are the names of seven African-Americans (among whom Sojourner Truth, Mary Church Terrell, and Ida B. Wells), a Chinese woman, a Hispanic woman and two militant socialists and trade unionists.

However, this project, unveiled in 2018, drew criticism from academia and the press. It is important to recall that the 2018 socio-political context was marked by the controversial presidency of Donald Trump, the rebirth of the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter’s activism, and the violence perpetrated in August 2017 by white supremacists in Charlottesville, North Carolina, during protests caused by the decision to remove the statue of Confederate leader Robert Lee.

Criticism reflected this tense context and was rooted in the revisionist historiography of suffragism, which for the past three decades has denounced Stanton and Anthony as racists striving to take control of the history and memory of the movement, notably through their

History of Woman Suffrage, a truly monumental work, which they conceived in the 1870s and edited in several volumes:

History of Woman Suffrage has long been considered the most reliable version of the movement’s history, but has been the subject of revision for over two decades:

Rosalyn Terborg-Penn (

1998), a pioneering historian of Black suffragism, has brought to light the invisibilization of African-American activists in

History of Woman Suffrage and in the movement more generally. Also worth mentioning is Lisa Tetrault’s groundbreaking book

The Myth of Seneca Falls (

Tetrault 2014), which presents

History of Woman Suffrage as a version produced in a divisive context of the movement that silences Black women’s participation and foregrounds Stanton and Anthony as the movement’s principal architects. More generally, Tetrault emphasizes the way in which Stanton and Anthony not only produced but commemorated their history of the movement, sacralizing the Seneca Falls convention as the true and unique beginning of the movement. The busts sculpted for the 1893 World’s Fair are a case in point. The construction of the movement’s memory is thus a form of activism that crowded out other aspects of suffragism and influenced historiography

4 (

Tetrault 2019).

Bergmann’s initial project, ironically, seems to suggest that Stanton and Anthony are indeed writing the history of suffragism. Gloria Steinem told the

New York Times that the two women seemed to be “standing on the names of these other women” (

Bellafante 2019), and critics have pointed to the presence of the ballot box, which seems to indicate that the 19th Amendment is the culmination of the movement, obscuring the fact that even after 1920, many women of color could not vote, particularly in the South. In recent historiography, it is not 1920 but 1965 which is considered the victory of a struggle that remains in some respects fragile (

Jones 2020;

Cahill 2020;

Dubois et al. 2019)

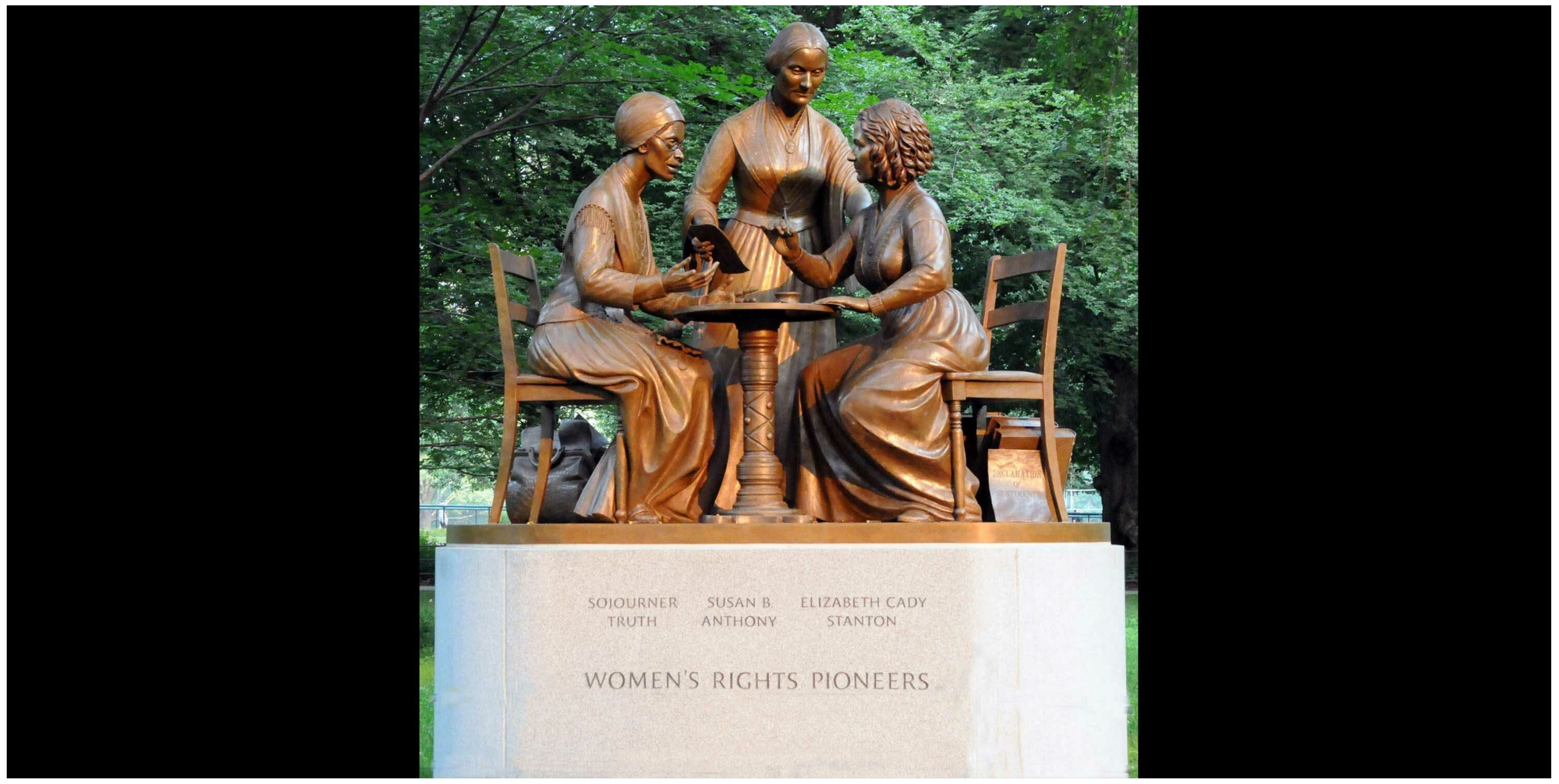

Faced with this controversy, in early 2019, Bergmann modified her project; she removed the urn and scroll and the name changed to

Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument (

Figure 4). However, these modifications failed to appease the critics in the press and academia. Author and journalist

Brent Staples (

2019) published several editorials in the

New York Times denouncing a “lilywhite version of history”. In an article published on 22 March 2019 in the

Washington Post, entitled “How New York’s New Monument Whitewashes the Women’s Rights Movement”, historian Martha Jones pointed out that the monument promoted the myth of a movement led by White women and celebrated activists steeped in racist prejudice. Jones pleaded for the inclusion of Sojourner Truth, arguing that “Her vision for women’s rights insisted that we imagine a nation in which women’s futures were no longer troubled by color, status and other man-made differences. That is a vision worth promoting, for our daughters and for ourselves” (

Jones 2019). Although the New York Park Design Commission approved the project, the figure of Sojourner Truth was eventually added by Bergmann. Discussions amended the original statue of Truth–originally shown seated away from the table with her hands on her knees– so as to present her as an active, equal-opportunity conversationalist. The knitting on her lap symbolizes a vital skill for working women who strove to keep their families warm (

Lange 2020).

However, the addition of Truth to the monument did not generate consensus. In a letter to Monumental Women, some 20 mostly African-American activists and academics criticized the project for giving the historically unfounded impression that Truth regularly collaborated with Stanton and Anthony and that Black and White women faced the same experiences of discrimination (

Small 2019).

In these debates, Monumental Women has always stressed its desire for an inclusive project and pointed out the many aesthetic and administrative constraints involved in erecting a statue in Central Park (

Monumental Women n.d.). Some members of Monumental Women, such as Myriam Miedzian and Coline Jenkins, (

Miedzian 2020) also defended Stanton and Anthony, recalling their enormous contribution to suffragism and stressing that racism was not dominant in the movement.

Miedzian, in particular, argues that the invisibility of Black suffragists was not the work of White activists but of the global erasure of women from history (

Miedzian 2020).

Inclusivity is a dimension that Monumental Women has emphasized (the association appointed women of color to its board of directors following the controversy), notably at the inauguration. Eventually, the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument was inaugurated by a small committee at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the personalities present, Hillary Clinton delivered a speech encouraging the future creation of commemorations in the service of women and people of color. The monument is also accompanied by a project of “talking statues” with famous actresses lending their voices to the suffrage pioneers.

5However, one may wonder whether these efforts adequately represent the diversity of the movement. And does not the heroization of Sojourner Truth, who has more monuments in the U.S. than Stanton and Anthony (

Rooney 2021), obscure the contribution of thousands of other suffragists and activists of color? In addition, one may reflect upon the quasi-systematic “addition” of Truth in 2005 and 2020 to somehow redress the White version proposed by the initial monuments. It looks as though Truth alone summed up Black suffrage activism and stood for Black feminism.

6To some extent, the addition of Portrait Monument and Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument to the US memorial landscape illustrates what Gerder Lerner called “compensatory history” and “contribution history” (

Lerner 1975, p. 2), i.e., the effort to add female figures to fill the gaps of traditional history. Lerner noted that while those stages were necessary, they remained insufficient:

Writing contribution history is to describe what men in the past told women to do and what men in the past thought women should be. This is just another way of saying that historians of women’s history have so far used a traditional conceptual framework. Essentially, they have applied questions from traditional history to women, and tried to fit women’s past into the empty spaces (italics mine) of historical scholarship”.

If we apply this to the commemoration of female historical figures, it becomes obvious that trying to fit feminist women’s statues “into the empty spaces” of the memorial landscape will not be enough. Thus, new memory frameworks must be invented to commemorate feminism.

3. What (Counter) Monuments for Suffrage and Feminism?

The controversies surrounding the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument have once again raised questions about the ways in which feminism is or should be commemorated. In an online article published in

Tom Dispatch,

Erin Thompson (

2020b) deplores the monument’s triumphalism, which suggests that the issue of women’s rights is a foregone conclusion today, and she problematically laments the fact that the scene depicted emphasizes the femininity and domesticity of the activists.

7 More broadly, critics have argued that bronze, pedestals, realistic figuration, and heroism are choices that reflect a traditional, patriarchal mode of memorialization that cannot correspond to feminism (

Small 2020), just as new criteria had to be created to write women’s history, a new memory paradigm needs to be invented.

Two trends have emerged in terms of suffrage and feminist monumental commemoration. The first one consists of transforming the bronze monuments, and the second is “breaking the bronze” through abstraction or countermonuments.

Rooney’s study reveals that the proportion of monuments to suffragism with multiple rather than single figures is not negligible (25%) and that this choice, made as early as the 19th century, challenges the perspective of the single man on a pedestal (

Rooney 2021).

Among the multi-subject monuments dedicated to suffragism, an important example is the first-wave statue sculpture inaugurated in 1992, commissioned by the National Park Service for women’s rights for the National Historical Park Visitor Center in Seneca Falls, NY. The work, composed of 20 life-sized bronze statues designed by Lillie Loyd (

Figure 5), pays homage to the organizers and participants of the 1848 Seneca Falls convention. With its inclusion of four male feminists, among whom James Mott and Frederick Douglass, and eleven anonymous participants, the monument somewhat departs from and enlarges the traditional narrative celebrating Stanton and Lucretia Mott as the main organizers and heroines of the event. The representation of couples, in particular, echoes the importance of suffrage activism within the domestic sphere and among family networks. Being life-sized and not placed on pedestals, the monument also invites a different relationship with the visitors, producing an impression of closeness.

The Project Women’s Boston Memorial (

Figure 6) unveiled in 2003 and designed by Meredith Bergmann, produces the same impression. The sculptures at the Commonwealth Avenue Mall honor three women, two of whom (Abigail Adams and African-American poet Phillis Wheatley) are not exactly suffragists but women who shaped the city. Bergmann chose to represent these women not on a pedestal but using their pedestals as props: Phillis Wheatley and Lucy Stone are shown using the stones as desks for their writings, and Adams is leaning cross-armed against hers. The artist’s intention was to invite the visitors to interact with these women and deconstruct the conventional vertical gaze that pedestals demand. To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the monument and enhance its “embodied” dimension, a talking statue app has been added (

https://wanderwomenproject.com/places/boston-womens-memorial/#google_vignette) (accessed on 30 November 2023).

Artist Meredith Bergmann’s vision displays a new way of thinking about public art. Unlike larger-than-life statues, these invite people to interact with them. Bergmann’s use of bronze, then, goes beyond the staticity usually found in the representation of male historical figures. Artist Jane DeDecker, a renowned sculptress from Colorado dedicated to honoring women and suffragists, also seeks to combat staticity:

My work is not static, nor is it a finished thought, but rather tied to a moment in time and place that reflects the unfinished story that is our humanity. The permanence of my sculptures cast in bronze drives me to respect the message I leave behind—positive affirmations about life ((

DeDecker n.d.a)

janededecker.com accessed on 30 November 2023).

DeDecker is famous for Ripples of Change, a set of four larger-than-life bronze statues representing Laura Cornelius Kellogg, Harriet Tubman, Martha Coffin Wright, and Sojourner Truth (

Figure 7). Inaugurated in Seneca Falls in 2021, the monument is not explicitly dedicated to suffragism but includes a Native American (Laura C. Kellog) belonging to the Haudenosaunee community whose “traditions and social structure [that] served as inspiration for the early suffragists in the pursuit of their inalienable rights” ((

DeDecker n.d.c) Ripples of Change). In the suffrage narrative, this monument somehow represents the prehistory of the Seneca Falls Convention through the water metaphor of the “ripples” of change that link each statue and facilitated the advent of the convention. While each detail surrounding the figures testifies to a close knowledge of the power and modes of activism of 19th-century women, it is striking that the monument honors yet again the so-called “first” women’s rights convention, as though moving beyond the “myth” deconstructed by Tetrault had not yet found its way in public art. One reason for this, I surmise, is that to fulfill its commemorative mission, there must exist some kind of shared and appealing narrative between the monument and the public.

DeDecker is also, among other things, the creator of a multi-subject monument that significantly transforms the vertical paradigm. Every Word We Utter (

Figure 8) is the title of this monument as well as that of a non-profit organization which, in the context of the national centennial celebrations, was chosen as the commissioning body by a bipartisan bill approving the creation of a suffrage monument in Washington DC in 2019. The bill was signed into law in December 2020.

“Every Word We Utter” officially signaled the suffrage movement’s consecration in the canon of US history. The artist was inspired by a letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Lucretia Mott in which she wrote about the power of words and deeds: “Every word we utter, every act we perform, waft unto innumerable circles, beyond.”

DeDecker explains that she “wanted to capture the collective energy from all women who have made this happen, as well as acknowledge that we still need to keep moving as we strive for equality” (

DeDecker n.d.b) Every Word We Utter.

This monumental sculpture, which is planned to be 20 feet high, depicts several generations of suffragists and includes African-American women, such as Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells. At the bottom of the sculpture stand Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth, and above them, Harriet Stanton Blatch, Alice Paul, and Ida B. Wells are represented. “Standing on the shoulders of giants, these women were elevated from what came before. From this height, the ratification flag cascades to the innumerable circles that ripple outwards” (

DeDecker 2015). Many other suffragists’ names are written at the base of the monument.

The interest in DeDecker’s project lies in its clearly inclusive scope and generational dimension; as Rooney notes, its honoring of multiple subjects “offers a possible solution to the reductivism of the public monument and its single-issue focus” (

Rooney 2021). Still, operating a selection among the many figures of suffragism automatically triggers a process of exclusion, and one may be surprised at the absence of prominent White and Black leaders such as Carrie Chapman Catt or Mary Church Terrell. In addition, the sculpture does not honor the figures of suffragists belonging to Asian, Native American, and Hispanic minorities who also played a part in the struggle and have only been recently rediscovered in an attempt to complicate and go beyond the Black/White binary of suffrage narratives (Cahill 6).

Despite these limits, DeDecker’s project, which will be shown at the heart of the nation’s capital, promises an inspirational dimension for the visitors and, more particularly, the women and young girls, which is what the artist wants.

However inspirational these bronze works may be, they also raise criticism pointing to their inability to properly honor the feminist movement. As Sally Roescher notes:

“When it comes to the feminist movement, monuments to individuals are an outstanding historic lie. Because women’s rights have been won by a steady history of millions of women and men, working together at best, separated at worst…” While this remark may apply, in truth, to any sweeping social movement, Roescher goes further by asserting that “To honor individuals is to disempower the movement itself”.

The inability of bronze monuments to commemorate the feminist movement is also related to the idea that bronze embodies a traditional form of commemoration that Nancy Small calls “a masculinist practice”. Thus, a truly new feminist memory framework should somehow “break the bronze” and invent other forms of commemoration.

A number of examples come to mind in this respect. The resort to abstraction, by primarily celebrating a concept rather than a particular individual, could address Roesch’s criticism. In 1996, the artist Louise Bourgeois sculpted a series of black granite hands that are presented on six four-foot-high, rough-hewn stone pedestals, exhibited in a Chicago park. Funded by the B.F. Ferguson Monument Fund, the work, entitled Helping Hands (

Figure 9), is to honor Jane Addams, the remarkable social worker and reformer who founded Hull House in the 19th century and turned out to be an ardent suffragist. Rooney notes: “Intended to evoke the ethos and impact of Addams without conveying a realistic likeness, the hands symbolize the broad spectrum of people whose lives Addams helped improve” (

Rooney 2021). Bourgeois’s work, which is one of the three abstract monuments listed by Rooney in the US, has been described by the Chicago art curator as a “monumental anti-monument with a significant feminist and enlightened point of view oriented toward civic action rather than self-importance, and as such significantly different than the bronze hero-on-a-horse memorials erected elsewhere in Chicago” (

Rooney 2021).

Antimonuments

8 have emerged in recent decades as a critical mode of commemorative practice. James E Young’s 1992 article “Memory against itself in Germany today” was instrumental in spreading the notion of countermonumentality, which he illustrated through the example of the 1986 Harburg monument denouncing fascism. The artists built a 12-m-high square pillar of hollow aluminum and invited the people to write their names on it, informing them that, with time, the pillar would be lowered into the ground until its complete disappearance. In Young’s words, the countermonument’s aim was as follows:

Not to console but to provoke; not to remain fixed but to change; not to be everlasting but to disappear; not to be ignored by its passersby but to demand interaction; not to remain pristine but to invite its own violation and desecration; not to accept graciously the burden of memory but to throw it back at the town’s feet. By defining itself in opposition to the traditional memorial’s task, the counter-monument illustrates concisely the possibilities and limitations of all memorials everywhere. In this way, it functions as a valuable ‘counter-index’ to the ways time, memory, and current history intersect at any memorial site.

How can these aims apply to feminism, a positive movement? The idea of a feminist monument inviting “its own violation and desecration” and programming its own disappearance seems shocking and counterproductive when it comes to remembering women and their history. Still, a number of feminist countermonuments have emerged recently, which significantly shift from traditional forms of commemoration and offer provocative alternatives.

One example is Dendrofemonology: A Feminist History Tree Ring, by artist Tiffany Shlain (

Figure 10), who chose a large cedar wood slice to inscribe a feminist timeline. The concentric circles of the tree symbolize for Shlain a symbol of female power as well as the idea that “progress doesn’t always work in one direction”. Supported by the National Women’s History Museum and displayed in San Francisco in 2022 and Washington DC in 2023, this work proposes a chronology going from 50,000 BCE, when “Goddesses are worshipped”, to 2022, when “Roe v Wade is overturned, eviscerating federal protection of reproductive rights in the United States”. Shlain’s work is not simply informative–recalling, for instance, that only in 1993 were women allowed to wear pants on the floor of the US Senate–it also invites visitors to answer a set of three questions: “What is the line on the timeline that is meaningful to you, and why?; What is something that is not on the timeline that is meaningful to you and why?; What do you hope is on there next?” (

National Women’s History Museum n.d.). The NWHM will publish the expanded timeline. Besides, Shlain’s monument is conceived as a moveable one that should “galvan[ize] collective actions in feminist interventions” (

Barrie 2023). On its inauguration day on the National Mall in Washington D.C., famous feminist voices, among whom Tarana Burke, initiator of the #MeToo marches, and 50 organizations coordinated by the ERA coalition delivered speeches (

Barrie 2023). Thus, in its choice of material (wood vs. bronze), form (circles vs. uprightness), and paradigm (openness vs. closure), Dendrofemonology can be considered a feminist countermonument that urges the public to remain vigilant.

Other recent examples of feminist countermonuments are explored by

Angela Shpolberg (

2023), who studied two memorials dedicated to the feminist anarchist Emma Goldman. Both are examples of “grassroots commemoration” that Shpolberg analyses as countermonuments. The first one is Emma Goldman’s tombstone, which has been covered in graffiti by admirers and sympathizers promising to continue her fight. Transforming an act of vandalism into an act of activism, the tomb-turned-monument continues to interact with its visitors and inspire them with the feminist and anarchist ideals that Goldman defended all her life. The other monument (2017) is located in her place of birth in Lithuania and consists of a sea buoy emitting flashing lights that transmit in Morse code Emma Goldman’s autobiography

Living My Life (1931) letter by letter. The artist Karolina Freino conceived her work, called “Confluence” (

Figure 11), as interactive and participative as the visitors were invited to use their phones to decode the messages and have access to Goldman’s words.

Goldman’s memorialization, which is co-constructed by the public, echoes what Nancy Small calls “feminist co-memoration”:

To release ourselves from the entrenched narratives and practices that traditional commemorations reinforce, we should recast public memory activities—including but extending beyond centennial celebrations—as feminist co-memorations. Whereas commemoration is univocal, controlling, and narrative-affirming, feminist co-memoration has the potential to be a re-membering together. By “re-membering,” I mean a collaborative reassessment and reassembly of our memories and of our commemorative practices as inspired by rhetorical feminist tactics and feminist rhetorical practices.

Small warns that commemorative practices turn people into passive recipients of a constructed memory and that “masculinist commemorative activities habituate us into submission”. She urges the women to question and dismantle the master narrative of suffrage, concentrated on an elite of White women and overlooking the western states’ activism, and adopt an intersectional approach that would enable all women to become active participants by “regarding their own memories of women’s struggles for equality and their own (dis)connections to the master narrative of suffrage”.