Processing of Positive Newborn Screening Results for Congenital Hypothyroidism: A Qualitative Exploration of Current Practice in England

Abstract

1. Introduction

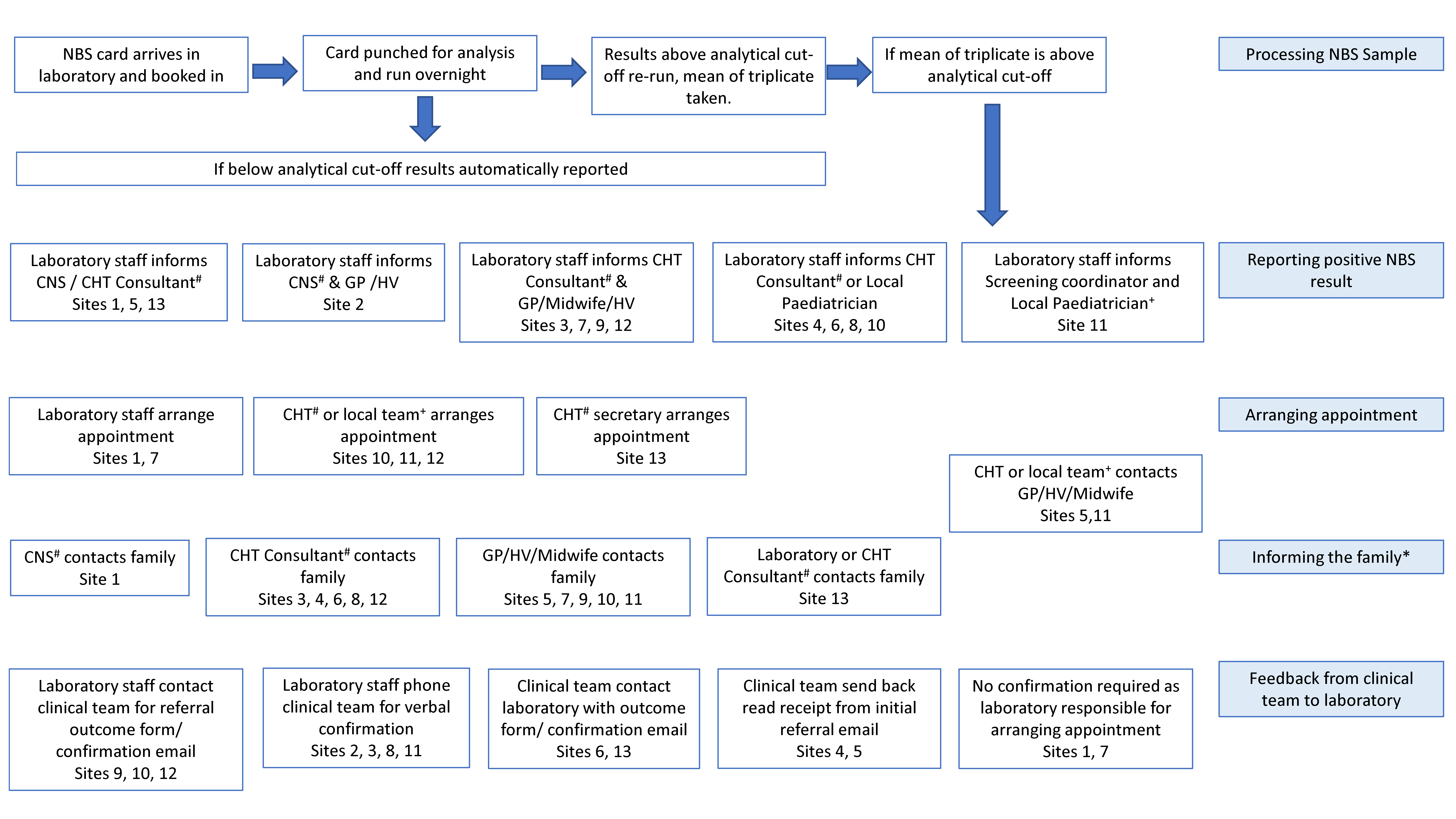

Communicating Presumptive Positive NBS Results for CHT

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Method of Referral from NBS Laboratory to Clinical Teams

“…congenital hypothyroidism is one of the most tricky referrals for us to do basically because we’re not phoning a team actually for that condition. …we get feedback saying, you know, ‘Why didn’t you contact the GP [Primary care practitioner]? It’s not me’… At different hospitals have slightly different ways that they want us to do it.”Study Site 6

“I would love it if I just had one person to call about all my hypothyroidism babies, make my life so much easier if I didn’t have to phone different GPs [Primary care practitioners] and different consultant endocrinologists.”Study Site 10

“… so that’s why we have to have a designated consultant. It’s a specific person who knows they’re going to do it so you never meet that barrier of, ‘Oh, I don’t want to do that. I’m not going to take that’. … So, I think because of that everybody pulls together really well.”Study Site 13

“The fact that we have a bleep number for the clinical teams that we’re trying to communicate to is helpful… I think just having a tight bleep list of people that you’re communicating with is positive.”Study Site 5

“So, whilst we have named contacts, sometimes trying to get hold of them can be difficult, particularly if, for example, contact hours have changed or people are on annual leave.”Study Site 4

“With the thyroids, it can be quite difficult to get hold of the appointment time, because if we can’t get the consultant… you may be waiting for them to call you back.”Study Site 1

“…it does sometimes feel like a bit of a battle trying to get hold of someone.”Study Site 3

“…long Bank Holiday weekends and things like that, working out how to, you know, make sure it’s processed in the correct way. … making sure we have a, sort of, set protocol for four-day weekends.”Study Site 12

“… there are pro-formas from Public Health England, but we happen to have one that we’ve been using for a long time. … Part of the problem we have with the pro-formas with Public Health England is that they’re not all in usable forms … we already had one in place that was already set up within our system that is easy for us to use.”Study Site 10

“I think if there was a set standard, for each condition, if there was a standard template for this referral, that every hospital, no matter which laboratory is making the referral, they all have the same form. … so that it’s all recognised… If every laboratory produces a different referral form, then it looks slightly different.”Study Site 11

3.2. Communication of PP Results from Clinicians to Families

“We do far less visits for CHT babies. They’re mainly phoned up and told about the results, and then told when the appointment is and where …It’s a lot simpler disorder.”Study Site 1

“…things like screening specialist nurses would be very useful actually”Study Site 2

“…if somebody else goes out… you don’t feel they’ll be about to field all the questions…it’s very much on how the person speaks to them, and what they say… we’ll always get some people who… didn’t know what it was, and didn’t know which test it was for.”Study Site 8

“…we do visits to thyroid babies…there’s kind of postcode lottery for that. That seems unfair.”Study Site 1

“…we sometimes have to play a bit of detective work to get the family.”Study Site 1

3.3. Arrangement of First Appointment

“I would ask for the endocrine team to take a little bit more responsibility in the arranging an appointment… That does take up quite a bit of the time… So, there’s probably a little bit of lack of trust on my part. It is probably why I tend to take a hands-on approach… I’m quite keen to see the job through. I don’t like handing over responsibility to anybody else because, you know, there’s a life at stake.”Study Site 7

“So, some clinicians like to see them very promptly, some are more relaxed in the timing, still within the guidelines. So, it’s not a consistent approach, whereas the other disorders are all very clear when the clinicians actually see the children. So, it makes it easier for the nurses to go out and contact the family.”Study Site 1

“There definitely is some variation between what tests are done, diagnostically, particularly with the congenital hypothyroidism… So, in terms of equity of care, it would seem that, given that it’s a national screening programme, people should be having the same tests for diagnosis as well.”Study Site 4

“One of the problems is that the congenital hypothyroidism screening and investigation is done differently in different parts of the UK, so this is a problem. So, there are some centres that do scans, some centres that don’t do scans, so there isn’t any uniform resource.” Study Site 9Study Site 9

3.4. Feedback from Clinical Teams to NBS Laboratories

“For congenital hypothyroidism… we refer to so many different consultants that it does vary between each trust. So, if we don’t receive feedback we have to phone and write letters, and that does take quite a bit of time… It’s purely because there isn’t a standardized approach as with the other conditions.”Study Site 1

“CHT is much more of a problem [compared to the other eight conditions included in the NBS programme] in this region because we are not phoning one individual consultant in this region… I have to chase around a lot more to get that information from other hospitals.”Study Site 10

“Then, what I will normally do then is email [the NBS laboratory] back to say, ‘Yes, the parents will be attending,’ and so on, or, if the parents declined, which has never happened, ‘Okay, they’re not coming,’ and I would assume they would follow up.”Study Site 7

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Questions That Need to Be Addressed in Future Work

- What is the best way to construct communication pathways that are independent of any single person and hence will not be disrupted by staff illness, holiday or a change in personnel?

- What is the best way to educate clinicians managing these babies so that there is comparable care around the nation, irrespective of the nature of secondary or tertiary centre involvement?

- What is the best way to standardise communication with families, particularly when delivered by HCPs who have less knowledge about CHT or are less experienced in delivering the news to improve care?

- What is the best way to organise care pathways that take into consideration the challenges that some families will face when accessing care?

- To what extent are existing barriers to more refined care a reflection of resource or funding issues and to what extent do they reflect factors independent of such factors?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Public Health England. Newborn Blood spot Screening Programme in the UK: Data Collection and Performance Analysis Report 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019; Public Health England: London, UK, 2021.

- Mansoor, S. Congenital Hypothyroidism: Diagnosis and management of patients. J Pak. Med. Assoc. 2020, 70, 1845–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.K.C.; Leung, A.A.C. Evaluation and management of the child with hypothyroidism. World J. Pediatr. 2019, 15, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, S.D.; Van Vliet, G. Prevention of intellectual disability through screening for congenital hypothyroidism: How much and at what level? Arch. Dis. Child. 2011, 96, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK National Screening Committee. A Laboratory Guide to Newborn Screening in the Uk for Congenital Hypothyroidism England; UK National Screening Committee: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–39.

- Menon, P.S.N. Prevention of Neurocognitive Impairment in Children Through Newborn Screening for Congenital Hypothyroidism. Indian Pediatr. 2018, 55, 113–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kanike, N.; Davis, A.; Shekhawat, P.S. Transient hypothyroidism in the newborn: To treat or not to treat. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, R.L.; Oerton, J.; Cheetham, T.; Butler, G.; Cavanagh, C.; Tetlow, L.; Dezateux, C. Newborn Screening for Primary Congenital Hypothyroidism: Estimating Test Performance at Different TSH Thresholds. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3720–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.L.; La Pean, A.; O’Tool, F.; Eskra, K.L.; Roedl, S.J.; Tluczek, A.; Farrell, M.H. Factors that influence parents’ experiences with results disclosure after newborn screening identifies genetic carrier status for cystic fibrosis or sickle cell hemoglobinopathy. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 90, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Farrell, M.H.; Kirschner, A.L.P.; Tluczek, A.; Farrell, P.M. Experience with Parent Follow-Up for Communication Outcomes after Newborn Screening Identifies Carrier Status. J. Pediatr. 2020, 224, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. Newborn Blood Spot Screening Programme in the Uk Data Collection and Performance Analysis Report 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018; Public Health England: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–59.

- Parker, H.; Qureshi, N.; Ulph, F.; Kai, J. Imparting carrier status results detected by universal newborn screening for sickle cell and cystic fibrosis in England: A qualitative study of current practice and policy challenges. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulph, F.; Cullinan, T.; Qureshi, N.; Kai, J. Parents’ responses to receiving sickle cell or cystic fibrosis carrier results for their child following newborn screening. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudleigh, J.; Buckingham, S.; Dignan, J.; O’Driscoll, S.; Johnson, K.; Rees, D.; Wyatt, H.; Metcalfe, A. Parents’ Experiences of Receiving the Initial Positive Newborn Screening (NBS) Result for Cystic Fibrosis and Sickle Cell Disease. J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 25, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudleigh, J.; Chinnery, H.; Holder, P.; Carling, R.S.; Southern, K.; Olander, E.; Moody, L.; Morris, S.; Ulph, F.; Bryon, M.; et al. Processing of positive newborn screening results: A qualitative exploration of current practice in England. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e044755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudleigh, J.; Ren, C.; Barben, J.; Southern, K. International approaches for delivery of positive newborn bloodspot screening results for CF. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2019, 18, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Glossary. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/Glossary (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- NHS Digital. Nhs data model and dictionary. Available online: https://datadictionary.nhs.uk/about/about.html (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Public Health England. Phe screening. Available online: https://phescreening.blog.gov.uk/about/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Public Health England. Congenital Hypothyroidism: Initial Clinical Referral Guidelines; Public Health England: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chudleigh, J.; Chinnery, H.; Bonham, J.R.; Olander, E.; Moody, L.; Simpson, A.; Morris, S.; Ulph, F.; Bryon, M.; Southern, K. Qualitative exploration of health professionals’ experiences of communicating positive newborn bloodspot screening results for nine conditions in England. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Newborn Blood Spot Screening: Programme Handbook; Public Health England: London, UK, 2018.

- Léger, J.; Olivieri, A.; Donaldson, M.; Torresani, T.; Krude, H.; van Vliet, G.; Polak, M.; Butler, G. European society for paediatric endocrinology consensus guidelines on screening, diagnosis, and management of congenital hypothyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, P.; Fitzgerald, C.; Somerville, R.; Linnane, B. Parental awareness of newborn bloodspot screening in Ireland. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 188, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salm, N.; Yetter, E.; Tluczek, A. Informing parents about positive newborn screen results. J. Child Health Care 2012, 16, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seddon, L.; Dick, K.; Carr, S.B.; Balfour-Lynn, I.M. Communicating cystic fibrosis newborn screening results to parents. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 180, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulph, F.; Cullinan, T.; Qureshi, N.; Kai, J. The impact on parents of receiving a carrier result for sickle cell or cystic fibrosis for their child via newborn screening. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder, M.; Timmermans, S. Newborn screening for metabolic disorders: Parental perceptions of the initial communication of results. Clin. Pediat. 2012, 51, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudleigh, J.; Bonham, J.; Bryon, M.; Francis, J.; Moody, L.; Morris, S.; Simpson, A.; Ulph, F.; Southern, K. Rethinking Strategies for Positive Newborn Screening Result (NBS+) Delivery (ReSPoND): A process evaluation of co-designing interventions to minimise impact on parental emotional well-being and stress. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford, C.; Kriel, Y.; Njau, I.; Nkole, T.; Gichangi, P.; Cordero, J.P.; Smit, J.A.; Steyn, P.S.; The UPTAKE Project Team. Teamwork in qualitative research: Descriptions of a multicountry team approach. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917727189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuir-Gunby, J.T.; Marshall, P.L.; McCulloch, A.W. Developing and Using a Codebook for the Analysis of Interview Data: An Example from a Professional Development Research Project. Field Methods 2010, 23, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, J.A.; Swift, P.G.; Anderson, W.; Turner, B.; Youth and Family Advisory Committee of Diabetes UK. Diabetes services in the UK: Fourth national survey; are we meeting NSF standards and NICE guidelines? Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Levels of Care | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Primary care | Healthcare delivered outside hospitals. It includes a range of services provided by primary care practitioners (known as general practitioners (GPs) in the UK), nurses, health visitors, midwives and other healthcare professionals as well as allied health professionals such as dentists, pharmacists and opticians. It includes community clinics, health centres and walk-in centres. |

| Secondary care | Secondary care is healthcare provided in local hospitals. It includes accident and emergency departments, outpatient departments, antenatal services, genitourinary medicine and sexual health clinics. |

| Tertiary care | Care for people needing complex treatments. People may be referred for tertiary care (for example, childhood cancer) from either primary care or secondary care. |

| Roles | |

| Clinical nurse specialist | Advanced nursing practitioners who can provide advice related to specific conditions or treatment pathways. |

| Consultant biochemist | Biochemists who oversee the diagnosis of disease, lead services and guide a wide range of healthcare staff. |

| Deputy/Director of NBS laboratory | Directors who are responsible for the overall operation and administration of the laboratory. |

| General paediatrician | Doctors who manage a range of medical conditions affecting children from birth to the age of 16. |

| Health visitor | Specialist community public health nurses, registered midwives or nurses, who specialise in working with families with a child aged 0 to 5. |

| Medical consultant | Senior doctors who practice in one of the medical specialties. |

| Midwife | Practitioners who are specially trained to deliver babies and to advise pregnant women. |

| Primary care practitioner | Known as ‘general practitioners’ (GPs) in the UK, who treat all common medical conditions and refer patients to hospitals and other medical services for urgent and specialist treatment. |

| Screening coordinator | Coordinators of screening programmes. |

| Screening specialist nurse | Advanced nursing practitioners who can provide advice related to specific screened conditions. |

| Senior/Clinical scientist | Care professionals who oversee specialist tests for diagnosing and managing disease and advise doctors on using and interpreting tests. |

| Registrar | Doctors in specialist training. |

| Process | UK Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Method of referral from laboratory to clinical team | Verbally and in writing using available template letters by secure email including a link to the standardised diagnostic and initial treatment protocol, to either an ‘expert paediatrician’ (member of a regional specialist paediatric endocrine team/lead paediatrician with a special interest in CHT) or a general paediatrician at a local centre with support from the ‘expert paediatrician’. |

| Time frame for communicating PP results to the clinical team | Same or next working day of the definitive NBS result being available. |

| Requirements when communicating PP results to families | Laboratory, ‘expert paediatrician’ or a deputy (depending upon the agreed regional protocol) notify an ‘informed health professional’, who provides the family with the appropriate information leaflet available via the screening programme and the child’s appointment details. |

| Time frame for first clinic appointment | Must take place on the same day or the next day after parents are informed of their babies positive NBS result. |

| Arrangements and follow-up for first clinic appointment | ‘Expert paediatrician’ or team managing the baby help to arrange access to diagnostic investigations and should report the outcome of the first appointment to the laboratory within 48 h. The laboratory then know that the child has entered the management pathway. |

| NBS Laboratory Staff | ||

| Profession | Number of Staff Interviewed | |

| Deputy/Director of NBS laboratory | 8 | |

| Senior/Clinical Scientist | 8 | |

| Consultant Biochemist | 1 | |

| Length of service | Median 10.5 years | Range 1.0–22.0 years |

| Length of interview | Median 32.46 min | Range 16.57–47.42 min |

| Clinical Teams | ||

| Profession | Number of staff interviewed | |

| Medical Consultant | 10 | |

| Clinical Nurse Specialist | 4 | |

| Screening Specialist Nurse/Midwife | 3 | |

| Screening Coordinator | 1 | |

| Length of service | Median 14.0 years | Range 2.0–23.0 years |

| Length of interview | Median 31.92 min | Range 19.16–54.58 min |

| Individuals Notified by Laboratory Team |

| Family |

| Primary care team |

| Secondary health care team |

| Tertiary health care team |

| Member of Staff Responsible for Initial Contact with Family |

| Clinical nurse specialist |

| General paediatrician (with/without specialist interest) |

| Health visitor |

| Laboratory staff |

| Midwife |

| Primary care practitioner |

| Registrar |

| Screening coordinator |

| Tertiary specialist |

| Method of Initial Contact with Family |

| Home visit |

| Phone call |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holder, P.; Cheetham, T.; Cocca, A.; Chinnery, H.; Chudleigh, J. Processing of Positive Newborn Screening Results for Congenital Hypothyroidism: A Qualitative Exploration of Current Practice in England. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7040064

Holder P, Cheetham T, Cocca A, Chinnery H, Chudleigh J. Processing of Positive Newborn Screening Results for Congenital Hypothyroidism: A Qualitative Exploration of Current Practice in England. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2021; 7(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolder, Pru, Tim Cheetham, Alessandra Cocca, Holly Chinnery, and Jane Chudleigh. 2021. "Processing of Positive Newborn Screening Results for Congenital Hypothyroidism: A Qualitative Exploration of Current Practice in England" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 7, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7040064

APA StyleHolder, P., Cheetham, T., Cocca, A., Chinnery, H., & Chudleigh, J. (2021). Processing of Positive Newborn Screening Results for Congenital Hypothyroidism: A Qualitative Exploration of Current Practice in England. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 7(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7040064