The Cost-Effectiveness of Expanding the UK Newborn Bloodspot Screening Programme to Include Five Additional Inborn Errors of Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

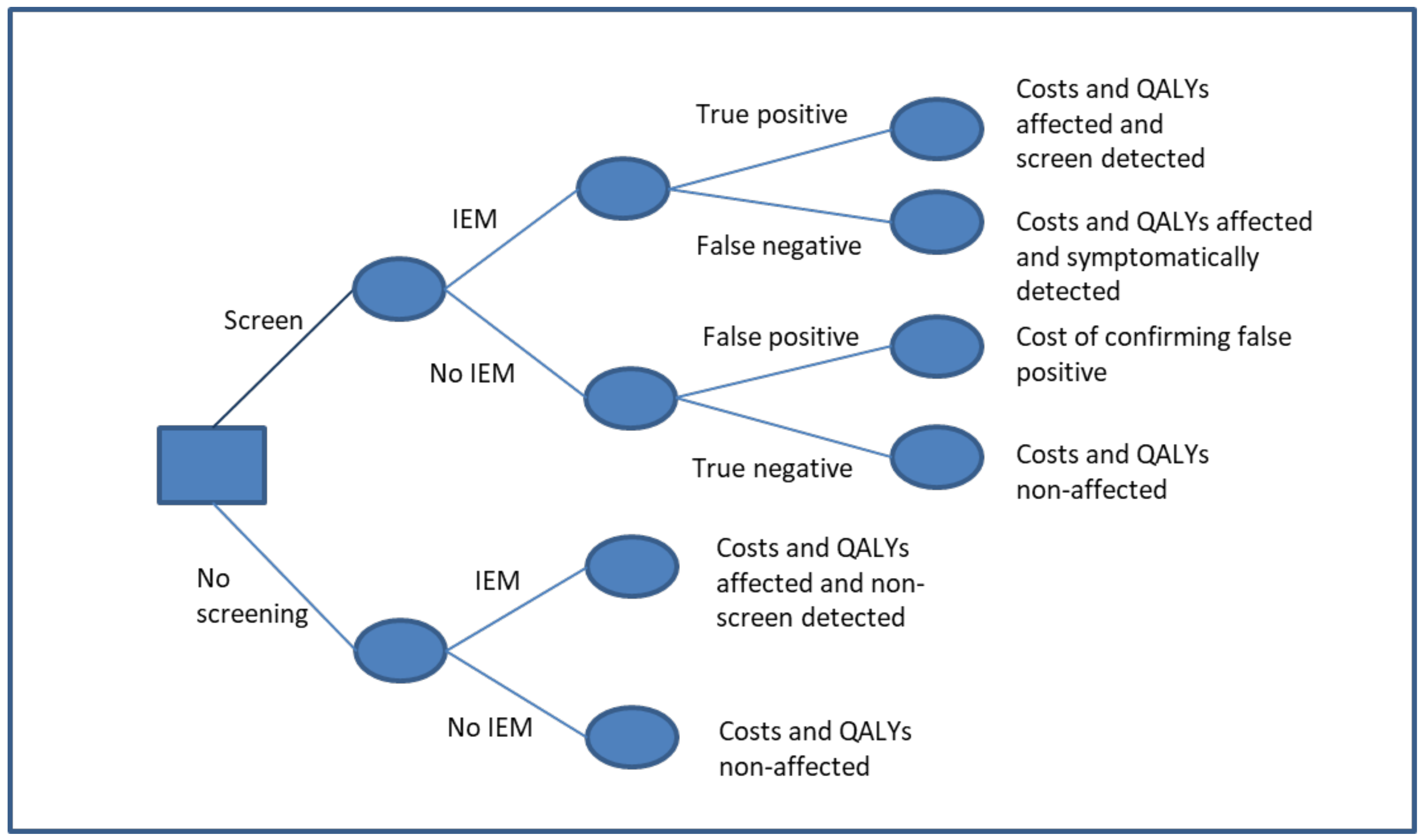

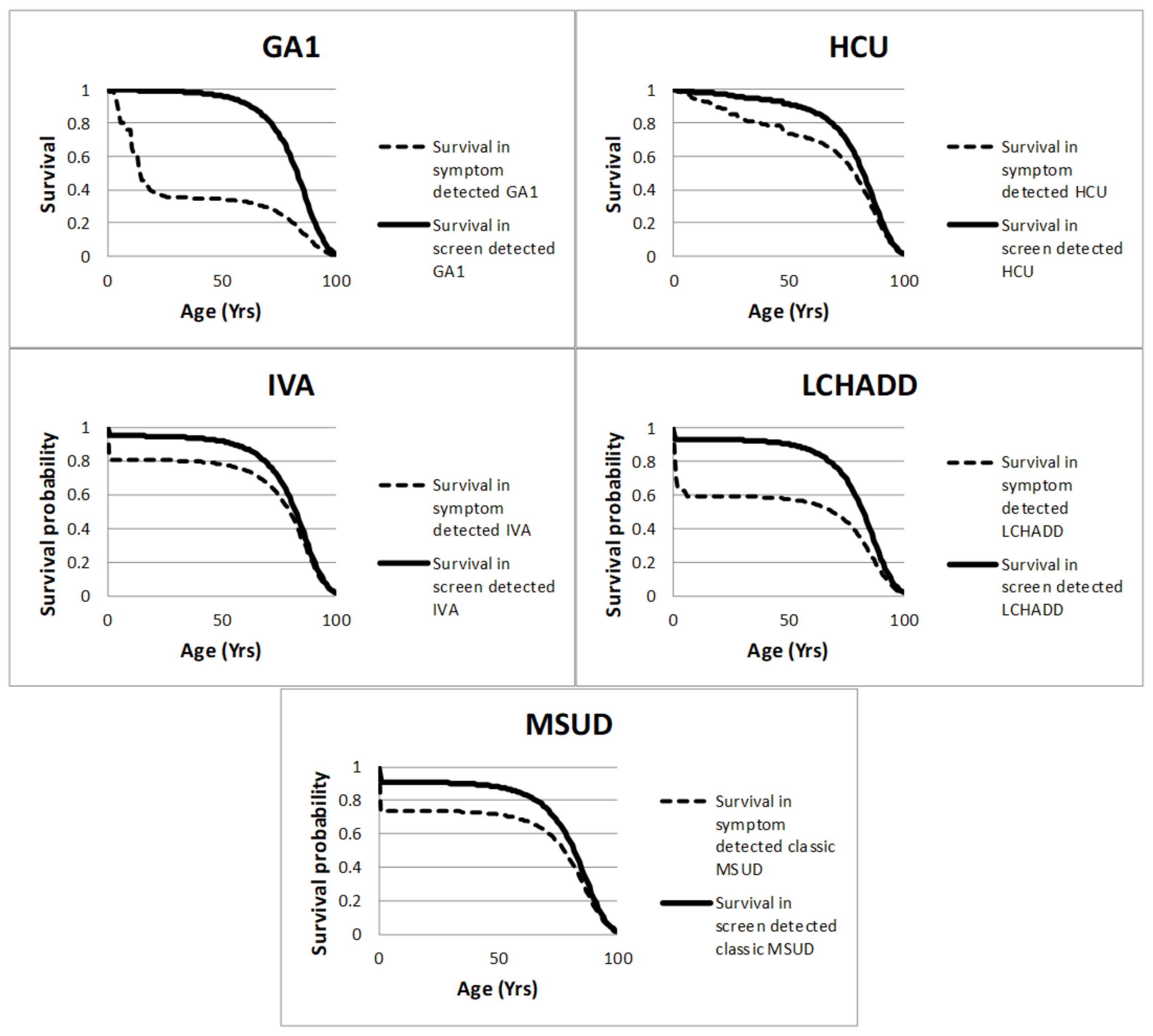

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life years |

| EVPI | Expected value of perfect information |

| EQ-5D | EuroQol-5D |

| EQ-5D+C | EuroQol-5D cognitive functioning |

| GA1 | Glutaric aciduria type 1 |

| HCU | Homocystinuria |

| ICER | Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio |

| IEM | Inborn error of metabolism |

| IVA | Isovaleric acidaemia |

| LCHADD | Long-chain hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| TMS | Tandem mass spectroscopy |

| MSUD | Maple syrup urine disease |

| PSS | Personal social services |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NSC | National Screening Committee |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| QALY | Quality-adjusted life year |

References

- Boer, M.E.J.D.; Wanders, R.J.A.; Morris, A.A.M.; Ijlst, L.; Heymans, H.S.A.; Wijburg, F.A. Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency: Clinical Presentation and Follow-Up of 50 Patients. Pediatrics 2002, 109, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünert, S.C.; Wendel, U.; Lindner, M.; Leichsenring, M.; Schwab, K.O.; Vockley, J.; Lehnert, W.; Ensenauer, R. Clinical and neurocognitive outcome in symptomatic isovaleric acidemia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd, S.H.; Skovby, F.; Levy, H.L.; Pettigrew, K.D.; Wilcken, B.; Pyeritz, R.E.; Andria, G.; Boers, G.H.J.; Bromberg, I.L.; Cerone, R.; et al. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1985, 37, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sykut-Cegielska, J.; Gradowska, W.; Piekutowska-Abramczuk, D.; Andresen, B.S.; Olsen, R.K.J.; Ołtarzewski, M.; Pronicki, M.; Pajdowska, M.; Bogdańska, A.; Jabłońska, E.; et al. Urgent metabolic service improves survival in long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency detected by symptomatic identification and pilot newborn screening. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011, 34, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, E.; Fingerhut, R.; Baumkötter, J.; Konstantopoulou, V.; Ratschmann, R.; Wendel, U. Maple syrup urine disease: Favourable effect of early diagnosis by newborn screening on the neonatal course of the disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2006, 29, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kölker, S.; Garbade, S.F.; Greenberg, C.R.; Leonard, J.V.; Saudubray, J.-M.; Ribes, A.; Kalkanoğlu, H.S.; Lund, A.M.; Merinero, B.; Wajner, M.; et al. Natural History, Outcome, and Treatment Efficacy in Children and Adults with Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 59, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcken, B.; Wiley, V.; Hammond, J.; Carpenter, K. Screening Newborns for Inborn Errors of Metabolism by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, H.; Moorthie, S. Expanded Newborn Screening: A Review of the Evidence; The PHG Foundation (Foundation for Genomics and Population Health): Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, N. Newborn babies will be tested for four more disorders, committee decides. BMJ 2014, 348, g3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.E.; Metternick-Jones, S.C.; Lister, K.J. International differences in the evaluation of conditions for newborn bloodspot screening: A review of scientific literature and policy documents. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Newborn Blood Spot Screening Programme in the UK: Data Collection and Performance Analysis Report 2016 to 2017. PHE 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/newborn-blood-spot-screening-data-collection-and-performance-analysis-report (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Public Health England. Newborn Blood Spot Screening Programme in the UK: Data Collection and Performance Analysis Report 2017 to 2018. PHE 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/newborn-blood-spot-screening-data-collection-report-2017-to-2018 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the Development of NICE Public Health Guidance, 3rd ed.; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moorthie, S.; Cameron, L.; Sagoo, G.S.; Bonham, J.R.; Burton, H. Systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the birth prevalence of five inherited metabolic diseases. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014, 37, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölker, S.; Garbade, S.F.; Boy, N.; Maier, E.M.; Meissner, T.; Mühlhausen, C.; Hennermann, J.B.; Lücke, T.; Häberle, J.; Baumkötter, J.; et al. Decline of Acute Encephalopathic Crises in Children with Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency Identified by Newborn Screening in Germany. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 62, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensenauer, R.; Vockley, J.; Willard, J.-M.; Huey, J.C.; Sass, J.O.; Edland, S.D.; Burton, B.K.; Berry, S.A.; Santer, R.; Grünert, S.; et al. A Common Mutation Is Associated with a Mild, Potentially Asymptomatic Phenotype in Patients with Isovaleric Acidemia Diagnosed by Newborn Screening. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 75, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunn, D.; Thomas, A.; Best, N.; Spiegelhalter, D. WinBUGS—A Bayesian modelling framework: Concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat. Comput. 2000, 10, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.H.; Burke, J.; O’Keefe, M.; Beighi, B.; Naughton, E.; Walsh, T.J. Ophthalmic abnormalities in homocystinuria: The value of screening. Eye 1998, 12, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.; Rushe, H.; Howard, P.M.; Naughten, E.R. The intellectual abilities of early-treated individuals with pyridoxine-nonresponsive homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2001, 24, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, L. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2012; University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. NHS Reference Costs 2011 to 2012. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-financial-year-2011-to-2012 (accessed on 4 July 2012).

- Sheffield Children’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Expanded Newborn Screening. Available online: http://www.expandedscreening.org/site/home/start.asp (accessed on 13 February 2012).

- Vetterly, C.G. BNF for Children 2009 by Paediatric Formulary Committee. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krabbe, P.F.; Stouthard, M.E.; Essink-Bot, M.-L.; Bonsel, G.J. The Effect of Adding a Cognitive Dimension to the EuroQol Multiattribute Health-Status Classification System. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1999, 52, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, P.; Hardman, G.; Macran, S. UK Population Norms for EQ-5D; Centre for Health Economics, University of York: Heslington, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, S.; Boers, G.H.; Wilcken, B.; Wilcken, D.E.; Brenton, D.P.; Lee, P.; Walter, J.H.; Howard, P.M.; Naughten, E.R. Vascular Outcome in Patients with Homocystinuria due to Cystathionine β-Synthase Deficiency Treated Chronically. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 2080–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreimeier, S.; Greiner, W. EQ-5D-Y as a Health-Related Quality of Life Instrument for Children and Adolescents: The Instrument’s Characteristics, Development, Current Use, and Challenges of Developing Its Value Set. Value Health 2019, 22, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, P.; Rose, J.; Jahoda, A.; Kroese, B.S.; Felce, D.; MacMahon, P.; Stimpson, A.; Rose, N.; Gillespie, D.; Shead, J.; et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial of a manualised cognitive behavioural anger management intervention delivered by supervised lay therapists to people with intellectual disabilities. Health Technol. Assess. 2013, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.A.; Gramer, G.; Viall, S.; Summar, M.L. Incidence of maple syrup urine disease, propionic acidemia, and methylmalonic aciduria from newborn screening data. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2018, 15, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroek, K.; Boelen, A.; Bouva, M.J.; Velden, M.D.S.D.; Schielen, P.C.J.I.; Maase, R.; Engel, H.; Jakobs, B.; Kluijtmans, L.A.J.; Mulder, M.F.; et al. Evaluation of 11 years of newborn screening for maple syrup urine disease in the Netherlands and a systematic review of the literature: Strategies for optimization. JIMD Rep. 2020, 54, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeil, J.; Listl, S.; Hoffmann, G.F.; Kölker, S.; Lindner, M.; Burgard, P. Newborn screening by tandem mass spectrometry for glutaric aciduria type 1: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwana, S.K.; Rascati, K.L.; Park, H. Cost-Effectiveness of Expanded Newborn Screening in Texas. Value Health 2012, 15, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.E.; Downs, S.M. Comprehensive Cost-Utility Analysis of Newborn Screening Strategies. Pediatrics 2006, 117, S287–S295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autti-Rämö, I.; Måkelå, M.; Sintonen, H.; Koskinen, H.; Laajalahti, L.; Halila, R.; Kååriåinen, H.; Lapatto, R.; Nåntö-Salonen, K.; Pulkki, K.; et al. Expanding screening for rare metabolic disease in the newborn: An analysis of costs, effect and ethical consequences for decision-making in Finland. Acta Paediatr. 2005, 94, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, L.E.; Rupar, C.A.; Zaric, G.S. The Cost-Effectiveness of Expanding Newborn Screening for up to 21 Inherited Metabolic Disorders Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Results from a Decision-Analytic Model. Value Health 2007, 10, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insinga, R.P.; Laessig, R.H.; Hoffman, G.L. Newborn screening with tandem mass spectrometry: Examining its cost-effectiveness in the Wisconsin Newborn Screening Panel. J. Pediatr. 2002, 141, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Norman, R.; Haas, M.; Chaplin, M.; Joy, P.; Wilcken, B. Economic Evaluation of Tandem Mass Spectrometry Newborn Screening in Australia. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, E.J.; Baker, J.C.; Colby, C.J.; To, T.T. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Universal Tandem Mass Spectrometry for Newborn Screening. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiboonboon, K.; Leelahavarong, P.; Wattanasirichaigoon, D.; Vatanavicharn, N.; Wasant, P.; Shotelersuk, V.; Pangkanon, S.; Kuptanon, C.; Chaisomchit, S.; Teerawattananon, Y. An Economic Evaluation of Neonatal Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heringer, J.; Valayannopoulos, V.; Lund, A.M.; Wijburg, F.A.; Freisinger, P.; Barić, I.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Burgard, P.; Burlina, A.B.; Chapman, K.A.; et al. Impact of age at onset and newborn screening on outcome in organic acidurias. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2016, 39, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couce, M.L.; Ramos, F.; Bueno, M.; Diaz, J.; Meavilla, S.; Bóveda, M.; Fernández-Marmiesse, A.; García-Cazorla, A. Evolution of maple syrup urine disease in patients diagnosed by newborn screening versus late diagnosis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2015, 19, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, F.-C.; Lee, H.-J.; Wang, A.-G.; Hsieh, S.-C.; Lu, Y.-H.; Lee, M.-C.; Pai, J.-S.; Chu, T.-H.; Yang, C.-F.; Hsu, T.-R.; et al. Experiences during newborn screening for glutaric aciduria type 1: Diagnosis, treatment, genotype, phenotype, and outcomes. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2017, 80, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viau, K.; Ernst, S.L.; Vanzo, R.J.; Botto, L.D.; Pasquali, M.; Longo, N. Glutaric acidemia Type 1: Outcomes before and after expanded newborn screening. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 106, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | MSUD Mean (95% CI) | HCU Mean (95% CI) | IVA Mean (95% CI) | GA1 Mean (95% CI) | LCHADD Mean (95% CI) | Distribution | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of long-term health and social care impact of inborn errors | No Screening | £585,845 (£431k, £778k) | £704,459 (£519k, £936k) | £262,377 (£193k, £349k) | £549,529 (£405k, £730k) | £636,641 (£469k, £846k) | Lognormal | [2] (IVA) [3,18,19] (HCU) [5] (MSUD) [15] (GA1) [20,21] (All Conditions) |

| Screening | £432,070 (£319k, £576k) | £82,193 (£61k, £109k) | £48,313 (£36k, £64k) | £170,644 (£126k, £227k) | £113,268 (£84k, £151k) | |||

| Incremental | −£153,775 | −£622,267 | −£214,064 | −£378,885 | −£523,373 | |||

| Cost of managing the IEM | No Screening | £445,933 (£327k, £589k) | £172,197 (£127k, £229k) | £171,859 (£127k, £229k) | £65,383 (£48k, £87k) | £81,900 (£60k, £109k) | Lognormal | [20,22,23] |

| Screening | £531,328 (£393k, £707k) | £235,730 (£174k, £312k) | £69,704 (£52k, £92k) | £70,793 (£52k, £94k) | £56,578 (£42k, £75k) | |||

| Incremental | £85,394 | £63,533 | −£102,155 | £5410 | −£25,322 | |||

| Life-time QALYs | No Screening | 14.17 (12.8, 15.6) | 22.74 (20.6, 25.0) | 29.90 (27.1, 32.9) | 8.40 (7.6, 9.2) | 17.80 (16.1, 19.6) | Lognormal | [2] (IVA) [3] (HCU), 5 (MSUD) [15] (GA1) [24] (HCU/IVA) [25] (GA1/LCHADD/MSUD) |

| Screening | 24.73 (23.3, 26.2) | 38.40 (35.3, 40.9) | 39.29 (36.4, 41.6) | 39.47 (36.7, 41.7) | 41.20 (39.2, 43.0) | |||

| Incremental | 10.56 | 15.66 | 9.40 | 31.07 | 23.40 | |||

| Costs of confirmation testing in positive screening | £582 (£524, £638) | £475 (£428, £521) | £896 (£807, £983) | £1052 (£948, £1154) | £555 (£500, £609) | Normal | [21] | |

| Screening test characteristics | Sensitivity | 88.47% (16.6%, 100%) | 93.26% (48.9%, 100%) | 93.80% (56.5%, 100%) | 90.72% (35.5%, 100%) | 89.35% (38.3%, 100%) | Normal (logit) | [8] |

| Specificity | 99.99% (100.0%, 100%) | 99.95% (99.7%, 100%) | 99.99% (99.9%, 100%) | 99.99% (99.9%, 100%) | 100% (100%, 100%) | Normal (logit) | [8] | |

| Incidence per 100,000 births | No Screening | 0.73 (0.60, 0.87) | 0.72 (0.52, 0.94) | 0.30 (0.17, 0.47) | 0.47 (0.26, 0.75) | 0.55 (0.40, 0.68) | Normal (logit) | [8,15] (GA1), [16] (IVA) [8,14] (All Conditions) |

| Screening | 0.74 (0.60, 0.87) | 0.74 (0.53, 0.95) | 0.83 (0.69, 0.97) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.17) | 0.65 (0.52, 0.79) | Normal (logit) | ||

| Incremental | 0.0003 | 0.02 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.10 | |||

| Sensitivity analysis: UK incidence per 100,000 births (2014–2018) | Screening and No Screening | 0.5 | 0.347 | 0.154 (0.386 including mild) | 0.309 | N/A (not screened for) | [11,12] | |

| Condition | Outcome | Normal | Mild Neurological or Psychiatric Disability | Moderate Neurological or Psychiatric Disability | Severe Neurological or Psychiatric Disability | References |

| QALY utility | 1 | 0.721 | 0.503 | 0.075 | [25] | |

| GA1 | Symptomatically detected | 10% | 0% | 20% | 70% | [15] |

| Screen-detected | 89.5% | 0% | 0% | 10.5% | [15] | |

| LCHADD | Symptomatically detected | 12% | 50% | 30% | 8% | Expert opinion |

| Screen-detected | 90% | 6% | 3% | 1% | Expert opinion | |

| MSUD Classic | Symptomatically detected | 10% | 50% | 30% | 10% | [5] Expert opinion |

| Screen-detected | 40% | 40% | 17.5% | 2.5% | [5] Expert opinion | |

| MSUD Intermediate | Symptomatic ally detected | 35% | 55% | 10% | 0% | [5] Expert opinion |

| Screen-detected | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | [5] Expert opinion | |

| Condition | Outcome | Normal | Learning disability | Mild developmental delay | Severe Developmental delay | |

| QALY decrement | 0 | 0.145 | 0.302 | 0.712 | [24] | |

| IVA | Symptomatic ally detected | 33% | 44% | 11% | 11% | [2] |

| Screen-detected | 82% | 9% | 9% | 0% | [2] | |

| HCU | Symptomatic ally detected | 25% | 0% | 25% | 50% | [3,19] |

| Screen-detected | 85% | 0% | 15% | 0% | [3,19] |

| Condition | No Screening | Screening | Incremental | Cost-Effectiveness (ICER) | Probability Cost Saving/Dominating | Probability Cost-Effective | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | QALYs | Cost | QALYs | Cost | QALYs | £15,000 per QALY | £20,000 per QALY | £25,000 per QALY | £30,000 per QALY | ||||

| Basecase analysis | MSUD | £7.58 (£5.65, £9.96) | 41.79340 (40.13948, 43.44516) | £7.30 (£5.50, £9.44) | 41.79347 (40.13953, 43.44524) | −£0.28 (−£2.42, £1.76) | 0.000069 (0.000012, 0.000097) | Dominating | 0.564 | 0.884 | 0.935 | 0.957 | 0.97 |

| HCU | £6.31 (£4.25, £9.01) | 41.79146 (40.14842, 43.43173) | £2.98 (£1.89, £5.18) | 41.79156 (40.14852, 43.43182) | −£3.33 (−£5.76, −£1.08) | 0.000101 (0.000051, 0.000153) | Dominating | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | |

| IVA | £1.31 (£0.69, £2.12) | 41.79356 (40.13962, 43.44532) | £1.20 (£0.90, £1.69) | 41.79358 (40.13964, 43.44534) | −£0.10 (−£0.97, £0.63) | 0.000014 (−0.000011, 0.000041) | Dominating | 0.59 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.787 | |

| GA1 | £2.87 (£1.48, £4.89) | 41.79344 (40.13949, 43.44511) | £2.72 (£2.05, £3.67) | 41.79356 (40.13962, 43.44534) | −£0.15 (−£2.14, £1.37) | 0.000120 (0.000034, 0.000218) | Dominating | 0.542 | 0.933 | 0.967 | 0.981 | 0.99 | |

| LCHADD | £3.94 (£2.65, £5.54) | 41.79347 (40.13955, 43.44524) | £1.54 (£1.00, £3.04) | 41.79358 (40.13966, 43.44536) | −£2.40 (−£4.04, −£0.76) | 0.000114 (0.000046, 0.000158) | Dominating | 0.997 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Increased uncertainty sensitivity analysis | MSUD | £7.60 (£4.69, £11.73) | 41.79340 (40.13947, 43.44516) | £7.30 (£4.64, £10.94) | 41.79347 (40.13953, 43.44524) | −£0.30 (−£4.53, £3.83) | 0.000069 (0.000012, 0.000105) | Dominating | 0.512 | 0.726 | 0.778 | 0.832 | 0.87 |

| HCU | £6.31 (£3.51, £10.62) | 41.79146 (40.14843, 43.43173) | £2.99 (£1.65, £5.38) | 41.79156 (40.14852, 43.43181) | −£3.32 (−£7.47, −£0.44) | 0.000101 (0.000031, 0.000164) | Dominating | 0.991 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | |

| IVA | £1.31 (£0.62, £2.35) | 41.79156 (40.14853, 43.43183) | £1.20 (£0.78, £1.87) | 41.79157 (40.14841, 43.43183) | −£0.11 (−£1.21, £0.79) | 0.000010 (−0.000049, 0.000048) | Dominating | 0.568 | 0.649 | 0.665 | 0.676 | 0.686 | |

| GA1 | £2.86 (£1.25, £5.58) | 41.79144 (40.14842, 43.43162) | £2.72 (£1.73, £4.23) | 41.79155 (40.14838, 43.43182) | −£0.13 (−£2.81, £1.92) | 0.000114 (0.000018, 0.000218) | Dominating | 0.518 | 0.899 | 0.932 | 0.956 | 0.977 | |

| LCHADD | £3.94 (£2.14, £6.70) | 41.79146 (40.14844, 43.43172) | £1.53 (£0.87, £3.10) | 41.79158 (40.14847, 43.43185) | −£2.40 (−£5.13, −£0.46) | 0.000111 (0.000041, 0.000161) | Dominating | 0.996 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| UK incidence rates: 2014–2018 | MSUD | £5.18 | 41.79346 | £5.03 | 41.79351 | −£0.15 | 0.000047 | Dominating | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HCU | £3.05 | 41.79153 | £1.61 | 41.79158 | −£1.44 | 0.000051 | Dominating | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| IVA | £0.67 | 41.79358 | £0.68 | 41.79359 | £0.01 | 0.000008 | £776 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| GA1 | £1.90 | 41.79350 | £1.07 | 41.79358 | −£0.83 | 0.000087 | Dominating | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Basecase ANALYSIS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | GA1 | HCU | IVA | LCHADD | MSUD | |

| Cost IEM | No screening | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 |

| Screening | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | £206 | |

| Cost Management | No screening | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 |

| Screening | £0 | £0 | £13 | £0 | £1229 | |

| QALYs | No screening | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 |

| Screening | £0 | £0 | £17,483 | £0 | £0 | |

| Screening Test | Sensitivity | £202 | £336 | £1421 | £21 | £3469 |

| Specificity | £77,769 | £1753 | £48,069 | £0 | £0 | |

| Cost | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | |

| Incidence | Screening | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 |

| No screening | £3078 | £0 | £162,786 | £0 | £0 | |

| Increased uncertainty sensitivity analysis | ||||||

| Parameter | GA1 | HCU | IVA | LCHADD | MSUD | |

| Cost IEM | No screening | £0 | £0 | £3218 | £0 | £5985 |

| Screening | £255 | £0 | £3936 | £0 | £64,737 | |

| Cost Management | No screening | £0 | £0 | £6 | £0 | £19 |

| Screening | £0 | £0 | £16,837 | £0 | £122,995 | |

| QALYs | No screening | £0 | £0 | £19,594 | £0 | £0 |

| Screening | £5793 | £0 | £319,310 | £0 | £0 | |

| Screening Test | Sensitivity | £349 | £59 | £2756 | £54 | £6262 |

| Specificity | £8628 | £1716 | £56,129 | £0 | £0 | |

| Cost | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | £0 | |

| Incidence | Screening | £0 | £0 | £894 | £0 | £0 |

| No screening | £9569 | £0 | £260,748 | £0 | £0 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bessey, A.; Chilcott, J.; Pandor, A.; Paisley, S. The Cost-Effectiveness of Expanding the UK Newborn Bloodspot Screening Programme to Include Five Additional Inborn Errors of Metabolism. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns6040093

Bessey A, Chilcott J, Pandor A, Paisley S. The Cost-Effectiveness of Expanding the UK Newborn Bloodspot Screening Programme to Include Five Additional Inborn Errors of Metabolism. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2020; 6(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns6040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleBessey, Alice, James Chilcott, Abdullah Pandor, and Suzy Paisley. 2020. "The Cost-Effectiveness of Expanding the UK Newborn Bloodspot Screening Programme to Include Five Additional Inborn Errors of Metabolism" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 6, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns6040093

APA StyleBessey, A., Chilcott, J., Pandor, A., & Paisley, S. (2020). The Cost-Effectiveness of Expanding the UK Newborn Bloodspot Screening Programme to Include Five Additional Inborn Errors of Metabolism. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 6(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns6040093