Training Primary Healthcare Professionals for Expanded Newborn Screening with Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Challenges for Community Genetics in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Basic Health Units in Porto Alegre

2.3. The Pilot Study on Including IEM Screening by MS/MS in NBS in Porto Alegre

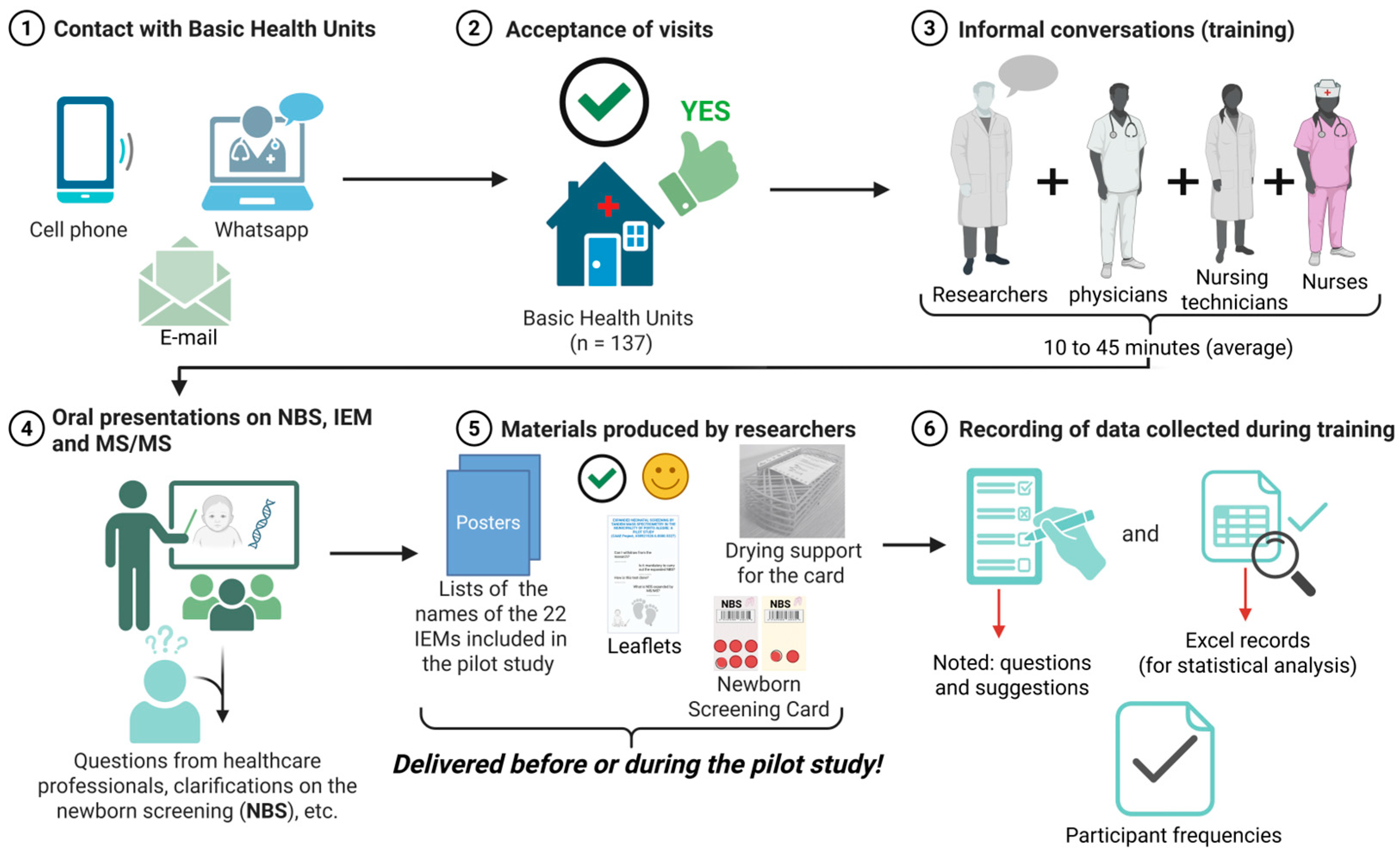

2.4. Visits to BHUs

- “Have you experienced any challenges during the pilot study?”;

- “Have you encountered issues using the research collection card?”;

- “Do you know what an IEMs is?”;

- “Have you heard about NBS using MS/MS?”;

- “Where are the NBS materials that were previously sent?”;

- “What is your level of satisfaction with the implementation of the pilot study?”

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Secretaria de Assistência à Saúde. Coordenação-Geral de Atenção Especializada e Temática. Triagem Neonatal Biológica: Manual Técnico.–Brasília; Ministério da Saúde: Brasilia, Brazil, 2016. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/triagem_neonatal_biologica_manual_tecnico.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Dias, L.R.; Tomasi, Y.T.; Boing, A.F. The Newborn Screening Tests in Brazil: Regional and Socioeconomic Prevalence and Inequalities in 2013 and 2019. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therrell, B.L.; Padilla, C.D.; Borrajo, G.J.C.; Khneisser, I.; Schielen, P.C.J.I.; Knight-Madden, J.; Malherbe, H.L.; Kase, M. Current Status of Newborn Bloodspot Screening Worldwide 2024: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Activities (2020–2023). Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, C.F.M.; Tonon, T.; Silva, T.O.; Bachega, T.A.S.S. Newborn Screening in Brazil: Realities and Challenges. J. Community Genet. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallmann, M.B.; Tomasi, Y.T.; Boing, A.F. Neonatal Screening Tests in Brazil: Prevalence Rates and Regional and Socioeconomic Inequalities. J. Pediatr. 2020, 96, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therrell, B.L.; Padilla, C.D.; Loeber, J.G.; Kneisser, I.; Saadallah, A.; Borrajo, G.J.C.; Adams, J. Current Status of Newborn Screening Worldwide: 2015. Semin. Perinatol. 2015, 39, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedat, F.; Taylor-Phillips, S. Teste de Triagem Neonatal: Expandir ou não expandir? Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2015, 68, 771–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, A.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Xiang, J.; Wang, B. Expanded Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism by Tandem Mass Spectrometry in Suzhou, China: Disease Spectrum, Prevalence, Genetic Characteristics in a Chinese Population. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, K.; Zhu, J.; Yu, E.; Xiang, L.; Yuan, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Incidence of Inborn Errors of Metabolism Detected by Tandem Mass. Spectrometry in China: A Census of over Seven Million. Newborns between 2016 and 2017. J. Med. Screen 2021, 28, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde. Ministério desenvolve ações para reestruturar o Programa Nacional de Triagem Neonatal. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2024/junho/ministerio-desenvolve-acoes-para-reestruturar-o-programa-nacional-de-triagem-neo (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- JusBrasil. Legislation. Law Creating a National Newborn Screening Program. Available online: https://www.jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/1218254408/lei-14154-21 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Brasil. Manual de Normas Técnicas e Rotinas Operacionais do Programa Nacional de Triagem Neonatal. Available online: https://www.saude.ce.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2018/06/livro_triagem_neonatal_pt1.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Mesquita, A.P.H.R.; de Marqui, A.B.T.; Silva-Grecco, R.L.; Balarin, M.A.S. Profissionais de Unidades Básicas de Saúde sobre a Triagem Neonatal. Rev. Ciências Médicas 2017, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística Porto Alegre (RS)|Cidades e Estados. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/rs/porto-alegre.html (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Da Costa, D.B.; Vannuchi, M.T.O.; Haddad, M.D.C.F.L.; Cardoso, M.G.P.; da Silva, L.G.; Garcia, S.D. Custo de educação continuada para equipe de Enfermagem de um Hospital Universitário Público. Rev. Eletronica Enfermagen 2012, 14, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.C.P.; Barreto, B.A.P.; Mesquita, R.P.P.; Moraes Júnior, R.F.d.O. Conhecimento sobre o teste do pezinho dos profissionais de saúde do estado do Pará. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Saúde 2025, 25, e18791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C.M. What Is Newborn Screening? N. C. Med. J. 2019, 80, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasem, A.; Razeq, N.M.A.; Abuhammad, S.; Alkhazali, H. Mothers’ Knowledge and Attitudes about Newborn Screening in Jordan. J. Community Genet. 2022, 13, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, C.M.; Law, E.C.; Lee, H.H.; Siu, W.; Chow, K.; Au Yeung, S.K.; Ngan, H.Y.; Tse, N.K.; Kwong, N.; Chan, G.C.; et al. The First Pilot Study of Expanded Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Survey of Related Knowledge and Opinions of Health Care Professionals in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med. J. 2018, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, B.; Ahmed, A.; Habib, A.; Turab, A.; Ali, N.; Soofi, S.B.; Nooruddin, S.; Kumar, R.J.; Tariq, A.; Shaheen, F.; et al. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices towards Newborn Screening for Congenital Hypothyroidism before and after a Health Education Intervention in Pregnant Women in a Hospital Setting in Pakistan. Int. Health 2018, 10, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, P.; True, B.; Walsh, J.; Dyson, M.; Lockwood, S.; Douglas, B. Maternal Attitudes and Knowledge about Newborn Screening. MCN Am. J. Matern./Child. Nurs. 2013, 38, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Transforming and Scaling Up Health Professionals’ Education and Training: World Health Organization Guidelines. 2013. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK298953/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Ceccim, R.B.; Feuerwerker, L.C.M. O quadrilátero da formação para a área da saúde: Ensino, gestão, atenção e controle social. Physis: Rev. Saúde Coletiva 2004, 14, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.A.; Baldim, L.B.; Nhoncanse, G.C.; Estevão, I.d.F.; Melo, D.G. Triagem Neonatal de Hemoglobinopatias no Município de São Carlos, São Paulo, Brasil: Análise de uma série de casos. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2015, 33, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araia, M.H.; Wilson, B.J.; Chakraborty, P.; Gall, K.; Honeywell, C.; Milburn, J.; Ramsay, T.; Potter, B.K. Factors Associated with Knowledge of and Satisfaction with Newborn Screening Education: A Survey of Mothers. Genet. Med. 2012, 14, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, O.Y.; Guevara, J.M.; Espejo-Mojica, Á.J.; Ardila, A.; Pulido, N.; Reyes, M.; Rodriguez-Lopez, A.; Alméciga-Díaz, C.J.; Barrera, L.A. Research, Diagnosis and Education in Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Colombia: 20 Years’ Experience from a Reference Center. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, U. Inborn Errors of Metabolism—Approach to Diagnosis and Management in Neonates. Indian J. Pediatr. 2021, 88, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.F.; Araújo, E.S.; Magalhães, J.C.; Silveira, É.A.; Tavares, S.B.N.; Amaral, R.G. Impacto da capacitação dos profissionais de saúde sobre o rastreamento do câncer do colo do útero em Unidades Básicas de Saúde. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs. 2014, 36, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrini, D.B.; da Silva, L.P.; Vieira, T.A.; Giugliani, R. Training of Community Health Agents–a Strategy for Earlier Recognition of Mucopolysaccharidoses. J. Community Genet. 2023, 15, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, J.K.L.; da Silva, L.M.; Santos, C.A.; Oliveira, I.d.S.; Fialho, G.M.; del Giglio, A. Assessment of Costs Related to Cancer Treatment. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2020, 66, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, P.F.; Santos, A.M.; Silva Cabral, L.M.; Anjos, E.F.; Fausto, M.C.R.; Bousquat, A. Water, Land, and Air: How Do Residents of Brazilian Remote Rural Territories Travel to Access Health Services? Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevenuto, R.G.; Azevedo, I.C.C.; Caulfield, B. Assessing the Spatial Burden in Health Care Accessibility of Low-Income Families in Rural Northeast Brazil. J. Transp. Health 2019, 14, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services: Interim Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-global-strategy-on-people-centred-and-integrated-health-services (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Mendes, C.A.; Guigen, A.P.; Anastácio-Pessan, F.L.; Dutka, J.C.R.; Lamônica, D.A.C. Knowledge of Parents Regarding Newborn Screening Test, after Accessing the Website “Babies’ Portal”–Heel Prick Test. Rev. CEFAC 2017, 19, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBGM—Sociedade Brasileira de Genética Médica e Genômica. Genética Médica na Atenção Básica de Saúde. Available online: https://www.sbgm.org.br/uploads/Cartilha_final.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- SBGM—Sociedade Brasileira de Genética Médica e Genômica. Genética para profissionais que atuam na Atenção Primária à Saúde no Brasil. Available online: https://www.sbgm.org.br/uploads/cartilha.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- SBTEIM—Sociedade Brasileira de Triagem Neonatal e Erros Inatos do Metabolismo. Ampliação do Teste do Pezinho no SUS: Um Dicionário para Profissionais da Saúde e a População; Sociedade Brasileira de Triagem Neonatal e Erros Inatos do Metabolismo: São Paulo, Brazil; Available online: https://sbteim.org.br/dicionario.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Vieira, T.A.; Trapp, F.B.; de Souza, C.F.M.; Faccini, L.S.; Jardim, L.B.; Schwartz, I.V.D.; Riegel, M.; Vargas, C.R.; Burin, M.G.; Leistner-Segal, S.; et al. Information and Diagnosis Networks–Tools to Improve Diagnosis and Treatment for Patients with Rare Genetic Diseases. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2019, 42, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items Produced by the Pilot Study | Basic Description of the Materials Presented in the Training |

|---|---|

| Posters | One poster for each BHUs listing the full names of the 4 IEMs groups (metabolism of fatty acids and ketone bodies [n = 8 diseases]; organic acidemia [n = 9 diseases]; aminoacidopathies [n = 3 diseases]; disturbances in the urea cycle [n = 2 diseases]). |

| Leaflets | Details of expanded neonatal screening by MS/MS, research telephone contacts, email addresses, etc. |

| Collection cards (modified) | More malleable paper than the collection cards used by the municipality. Collection card (modified) for use in research contained two copies (yellow and white card, with 8 circles printed on the filter paper attached to the card), with a label and place to describe the neonatal collection |

| N (137) | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ① Bad | 0 | 0 |

| ② Regular | 0 | 0 |

| ③ Intermediate | 4 | 2.9% |

| ④ Good | 43 | 31.4% |

| ⑤ Excellent | 90 | 65.7% |

| Main Subjective Questions | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Complaints about collection cards (modified) 1 | 18 (13.1%) | 119 (86.9%) |

| Questions about IEMs 2 | 55 (40.1%) | 82 (59.9%) |

| There was a poster or leaflet 3 | 93 (67.9%) | 44 (32.1%) |

| Other complaints 4 | 35 (25.5%) | 102 (74.5%) |

| Financial resources for families 5 | 14 (10.2%) | 123 (89.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reis, L.C.; Tonon, T.; Acosta, M.B.; Castro, S.M.d.; Coutinho, V.d.L.S.; Melo, D.G.; Schwartz, I.V.D. Training Primary Healthcare Professionals for Expanded Newborn Screening with Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Challenges for Community Genetics in Brazil. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030051

Reis LC, Tonon T, Acosta MB, Castro SMd, Coutinho VdLS, Melo DG, Schwartz IVD. Training Primary Healthcare Professionals for Expanded Newborn Screening with Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Challenges for Community Genetics in Brazil. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2025; 11(3):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030051

Chicago/Turabian StyleReis, Luzivan Costa, Tassia Tonon, Marina Bernardes Acosta, Simone Martins de Castro, Vivian de Lima Spode Coutinho, Débora Gusmão Melo, and Ida Vanessa Doederlein Schwartz. 2025. "Training Primary Healthcare Professionals for Expanded Newborn Screening with Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Challenges for Community Genetics in Brazil" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, no. 3: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030051

APA StyleReis, L. C., Tonon, T., Acosta, M. B., Castro, S. M. d., Coutinho, V. d. L. S., Melo, D. G., & Schwartz, I. V. D. (2025). Training Primary Healthcare Professionals for Expanded Newborn Screening with Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Challenges for Community Genetics in Brazil. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 11(3), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030051