Abstract

Vulvar carcinoma is the fourth most common gynecological cancer, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most frequent type. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a precursor lesion and is strongly associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. This paper presents two patients in their sixth decade of life, the first diagnosed with VIN 3 (carcinoma in situ) and the second with stage IA keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Both patients had HPV infection; immunohistochemistry confirmed HPV-dependent VIN3 in the first case, while the second patient had a pre-existing HPV high-risk 53 infection. Both patients underwent partial vulvectomy, with the second also having bilateral inguinal–femoral lymph node dissection, which showed no lymph node invasion. The first patient had a histopathological result of VIN 3 with clear margins. The second patient underwent adjuvant radiotherapy following restaging pathology. Both are showing favorable postoperative progress. Conclusions. The early diagnosis of vulvar neoplasms enables less radical but effective surgeries, balancing oncologic control with quality of life. A multidisciplinary approach is essential for adjusting treatments, improving both clinical outcomes and patient well-being.

1. Introduction

Vulvar carcinoma is the fourth most common gynecological cancer, accounting for up to 5% of all genital malignancies. It accounts for approximately 0.3% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases each year, with an incidence rate of 2.6 per 100,000 women annually. The diagnosis is usually made between the sixth and eighth decades of life and is often detected in its early stages [1].

The majority of cases are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), while less common subtypes include basal cell carcinoma (BCC), extramammary Paget disease, and vulvar melanoma [2]. The squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva accounts for 90% of cases, with 30–40% linked to high-risk HPV infection. The pathogenic mechanism involves the viral oncogenes E6 and E7, which inactivate the tumor suppressor proteins p53 and RB. An alternative pathway involves inflammation-induced cellular changes without p53 inactivation, leading to the suppression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A [3,4]. As the second most common vulvar malignancy, vulvar melanoma comprises 5% of all vulvar cancer cases. It primarily affects white women aged 50 to 70, with a median diagnosis age of 68 years, similar to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). However, approximately 8.4% of cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage, contributing to a lower survival rate [5,6].

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is the precursor lesion for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and is histopathologically categorized into the HPV-dependent usual type (uVIN) and HPV-independent differentiated type (dVIN). According to the 2014 WHO classification of vulvar tumors, uVIN is further divided into a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) [7,8]. uVIN progresses to SCC in 5% of cases, more frequently in the basaloid or warty subtypes, yet it accounts for approximately 40% of all SCC cases. It is more common in younger, smoking patients and has characteristic immunohistochemical (IHC) features: p16-positive and p53-negative [4,9]. dVIN progresses to keratinized SCC in only 5% of all VIN cases, but it is more frequently associated with malignant transformation, accounting for 35% of vulvar SCC precursor lesions. It most commonly develops from chronic dermatoses, such as lichen sclerosus or lichen planus. Its histological features include basal epithelial atypia, with IHC characteristics of p16-negative and p53-positive staining [8,10].

Vulvar SCC is histologically categorized into three types: basaloid, warty, and keratinizing. The basaloid and warty types are linked to HPV infection and are most commonly observed in individuals aged 40–44. In contrast, the keratinizing type is independent of HPV, occurs more frequently in older individuals, and represents 60 to 80 percent of vulvar SCC cases. It is typically located on the labia majora and perineum [11].

Regarding risk factors for vulvar cancer, attention should be given to precursor lesions like VIN. Low-grade lesions, such as condyloma acuminatum (anogenital warts) are associated with low-risk HPV strains (types 6 and 11) and do not progress to invasive cancer. Other risk factors include smoking and immunosuppression [12]. High-grade lesions are linked to high-risk HPV strains, most commonly types 16, 33, 18, and 31, and are more frequent in younger patients. Classic risk factors for HPV infection, such as marital status, oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy during menopause, and smoking, also play a role [4,13,14]. dVIN lesions, not associated with HPV, are driven by chronic inflammation, oxidative and ischemic stress, and p53 mutations. The risk of progression to SCC is higher in patients with lichen sclerosus and VIN lesions than in those with lichen sclerosus alone [15,16].

The 2021 FIGO staging system for vulvar carcinoma is based on key parameters, including tumor size, the depth of invasion, the extent of local spread, lymph node involvement, and the presence of regional or distant metastases (Table 1) [17].

Table 1.

FIGO staging for vulvar carcinoma (2021) [17].

2. Case Reports

This paper will present two cases: Patient A, diagnosed with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in situ (VIN3 lesions) and Patient B, diagnosed with stage IA keratinizing vulvar squamous cell carcinoma.

2.1. Patient A

This is a 57-year-old postmenopausal, smoker patient, menopausal for five years, who presented to our clinic with a vulvar tumor evolving for approximately two years. Her obstetric history includes one vaginal delivery and one abortion. Her medical history is significant for pulmonary tuberculosis (1993), psoriasis, and chronic hepatitis B infection (since 1994). Family history: the patient’s mother had breast cancer and passed away, while her brother was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

On clinical examination, the right labia minora exhibits an indurated lesion approximately 3 × 2 cm in size, with irregular borders and a whitish, scaly surface, extending across its entire inner aspect. The left labia minora appears normal (Figure 1). The cervix has a normal volume with no visible macroscopic abnormalities. The uterus is retroverted, of normal size, mobile, and non-tender. The adnexal regions are supple, and the vaginal fornices are intact.

Figure 1.

The clinical appearance at presentation shows a right labium minora that is hardened, with a tumor-like formation of approximately 3 × 2 cm.

The tumor formation is excised and sent for histopathological examination, which reveals surface malpighian epithelium (composed of the stratum basale and stratum spinosum) with keratinization and severe dysplasia (VIN3) diffusely, along with a focus of squamous cell carcinoma in situ at the margin of the specimen. Immunohistochemical tests for five markers are suggestive of severe vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN3) associated with HPV: p16 is diffusely and intensely positive in the areas of severe intraepithelial dysplasia, p53 is weakly and moderately positive in the nuclei of some squamous epithelial cells in the VIN3 areas, Ki67 is intensely positive in the nuclei of frequent squamous epithelial cells in the VIN3 areas (more than half the total thickness of the dysplastic epithelium), Her2/neu is negative, and AE1/AE3 is intensely positive. HPV testing was not performed in this case due to financial reasons, as it is not covered by insurance in our country.

The MRI evaluation of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast reveals hepatic steatosis, with no significant changes in the pelvic region, post-operative status following vulvar tumor surgery, and no nodular formations detectable at this level.

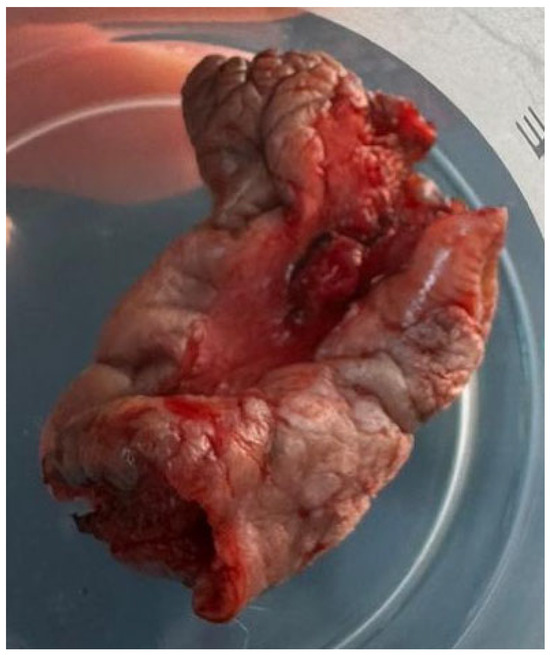

The patient is evaluated in a multidisciplinary oncology committee, and a surgical indication is established, with post-operative oncological reassessment. A partial right vulvectomy is decided and performed, with the excised specimen sent for histopathological examination using paraffin. Figure 2 shows the macroscopic specimen. Figure 3 shows the appearance at the end of the procedure.

Figure 2.

The partial vulvectomy specimen measured 5.5 × 3.5 × 3.2 cm and contained, at its center, the lesion described in the first figure.

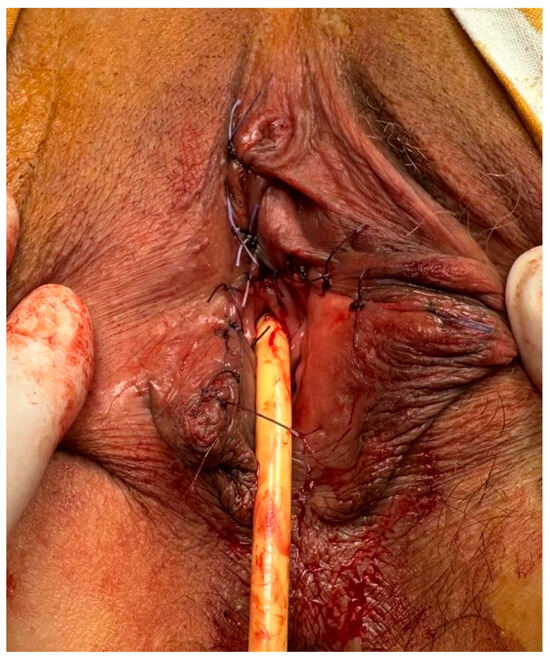

Figure 3.

The immediate postoperative appearance after right partial vulvectomy—the urethra, clitoris, vaginal introitus, and left labia were preserved.

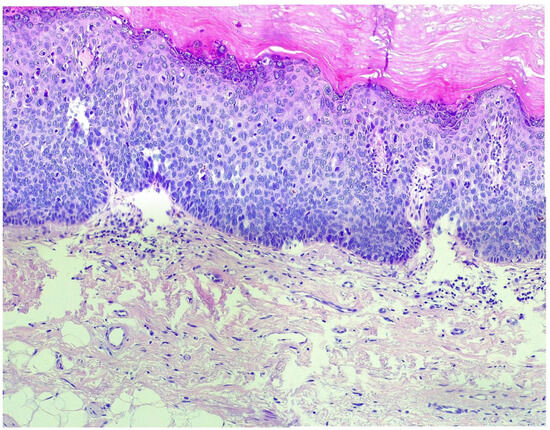

The histopathological result was VIN3 with clear surgical margins (Figure 4). This tissue fragment presents keratinized squamous malpighian epithelium with various lesional changes, including areas consistent with VIN3 (squamous cell carcinoma in situ), associated with an abundant lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate in the underlying stroma. The examined fragments show clear margins both at the excisional edges and in depth.

Figure 4.

In the histopathological examination using hematoxylin–eosin staining at 20× magnification, VIN3 (vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3) shows severe dysplastic changes in the epithelial layers. The squamous epithelium exhibits hyperchromatic nuclei, an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, irregular nuclear contours, and frequent mitotic figures. The basal layer shows marked atypia with an expansion of the dysplastic cells into the superficial layers. The architecture of the epithelium is distorted, and there is a loss of normal maturation of the epithelial cells, characteristic of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. The presence of severe disorganization and atypical cell features is consistent with VIN3.

2.2. Patient B

The second patient is a 57-year-old woman, menopausal for 12 years and a former smoker, who presents to our clinic with a vulvar tumor that has increased in size over the past 3 weeks. A month prior, she presented for a follow-up visit complaining of vulvar pruritus. Urine culture revealed a urinary tract infection, which was treated according to the antibiotic sensitivity; however, symptoms only partially resolved. Clinically, at this moment, only an erythematous area was observed. Her last Pap smear, performed 3 months prior, was negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy, while HPV genotyping was positive for the high-risk 53 strain. Notable medical history includes grade II hypertension with high additional risk, dyslipidemia, a meningioma operated on in 2005 (with recurrence 2 years prior, treated with a gamma knife), epilepsy under treatment, depressive syndrome, gastric sleeve surgery 1.5 years prior, and cholecystectomy. Family history reveals that the patient’s mother was diagnosed with type II diabetes mellitus.

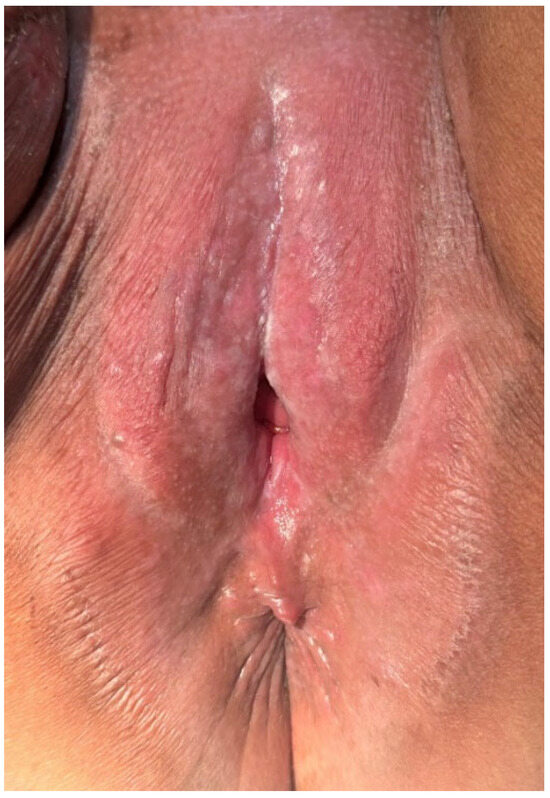

On clinical examination and vulvoscopy, a faint labial relief is observed at the level of the upper third of the vaginal introitus, including the urethral meatus, with a leukoplakic firm area extending approximately 2–3 cm toward the vaginal wall, containing multiple atypical vascular zones (Figure 5). At the posterior vulvar commissure, the leukoplakic area extends approximately 3 cm, without vascular anomalies. On ultrasound, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes with a suspicious appearance are detected (measuring between 12 and 15 mm and showing an inflammatory aspect, but given the suspicion of vulvar neoplasia, they were considered potentially malignant). The subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination ruled out this suspicion.

Figure 5.

The clinical appearance approximately six weeks after the initial visit, indicating a rapidly progressing lesion.

A vulvar biopsy is performed, and the fragments are sent for histopathological examination, which confirms a diagnosis of keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma with keratotic pearls invading the stroma of the collected sample. Immunohistochemical tests confirm an HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma with a null p53 phenotype: p16 absent in tumor cells, p53 showing a complete absence of nuclear reaction in tumor cells, suggesting a truncated mutation in the TP53 gene with a null phenotype, EGFR showing basal and basolateral membrane reactions with low intensity in 20% of tumor cells, scoring 1+, and Ki67 showing nuclear reaction in 60% of tumor cells.

The patient undergoes a pelvic MRI with contrast, which reveals a right vulvar lesion with irregular contours, with an axial diameter of 18/7 mm and non-homogeneous gadolinium enhancement, slightly extending into the adjacent tissue. The bladder is in semi-repletion, with homogeneous content, without the thickening of the walls suggestive of a tumoral or inflammatory nature at the level of the rectum or sigmoid (FIGO stage IA). Three weeks after the biopsy, a gynecological examination reveals a hard area in the upper third of the vaginal introitus, with an ulcerative appearance, involving the clitoris and a continuity defect at the level of the left labium minora, caused by tissue necrosis.

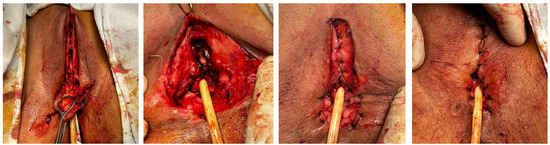

After the multidisciplinary oncology board meeting, the surgical indication is established, and partial vulvectomy with bilateral inguino-femoral lymph node dissection is performed (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The postoperative evolution is favorable, and the patient is discharged with the recommendation to keep the urinary catheter in place for up to 3 weeks postoperatively.

Figure 6.

Serial intraoperative views following excision of the partial vulvectomy specimen—the distal urethra was partially preserved, and the vaginal introitus was preserved.

Figure 7.

The partial vulvectomy specimen measuring 4.8 × 2.9 × 2.7 cm centered on the lesion at the level of the anterior vulvar commissure, extending towards the urethra, the distal third of the vaginal introitus, and the posterior vulvar commissure.

The histopathological examination describes moderately differentiated keratinizing squamous carcinoma (G2), infiltrative, with perineural, perivascular invasion, and vascular tumor invasion with a diffuse peritumoral lymphocytic inflammatory process, vascular stasis, and edema. On the peripheral lateral marginal fragments of the tumor, fibroconnective tissue lined by malpighian epithelium with keratinization is observed. In the deeper fragments, tumor invasion is present without clear safety margins. Sixteen lymph nodes were isolated, showing reactive lymphadenitis. The final diagnosis was keratinizing vulvar squamous carcinoma pT2N0Mx (FIGO II). Pathological restaging is common, with the final diagnosis being made after the radical intervention. Current clinical guidelines recommend adjuvant radiotherapy in pT2 cases, which was also performed for this patient. Subsequently, the patient undergoes 33 sessions of radiotherapy. The final appearance is described in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The appearance after radiation therapy sessions—organ functionality was preserved through proper case management. A suggestive post-radiation vulvitis was observed, which was treated conservatively.

3. Discussions

This case is notable because both patients are relatively young, whereas vulvar cancer is typically more prevalent in individuals over 60. A 2017 study examining vulvar cancer incidence trends in high-income countries found a significant rise in cases among women under 60 over the past two decades. This increase is likely linked to shifts in sexual behavior and greater HPV exposure among those born in the latter half of the 20th century [18]. A 2024 study analyzing demographic characteristics in the epidemiology of vulvar cancer found the highest overall incidence in the 70–84 age group (33.12%), followed by the 55–69 age group (29.42%), 0–39 years (18.41%), and ≥85 years (14.57%) [19].

These two cases, although seemingly similar at first glance, stand out through several differences, most likely correlated with the precursor lesion. Regarding HPV infection, it was suggested to exist by IHC tests in the first patient; however, due to the aforementioned reasons, genotyping could not be performed. Most likely, HPV testing would have been positive in this patient, and it would also have been useful in screening for other gynecological pathologies associated with HPV infection. In contrast, the second patient had a previously known diagnosis of high-risk HPV infection (strain 53) before her oncologic diagnosis. This highlights the fact that pre-existing information should not always be applied in an absolute manner, as there are cases of HPV-independent vulvar carcinoma that coincidentally associate an HPV infection without a causal relationship between the two events. However, HPV status may influence disease prognosis, as shown in a systematic review from 2018, which included 18 studies and concluded that HPV-positive vulvar cancers have a more favorable prognosis compared to HPV-negative cases. This could be explained by the fact that the phenotype associated with HPV infection is more sensitive to radiotherapy [20].

Concerning the medical history of the two patients, smoking was identified as a risk factor in both cases. Additionally, in the first patient, the altered immune status secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis, chronic HBV infection, and psoriasis may have played a role in the pathogenesis of the VIN3 lesion.

In reference to IHC characteristics, the second patient exhibited a p53 null phenotype, indicating a complete absence of gene expression. This detail could be correlated with the pre-existing HPV-53 infection. A 2020 study evaluating IHC patterns of p53 in HPV-associated neoplasms of the female lower genital tract demonstrated an inverse proportional relationship between viral load and p53 gene expression. Among other malignancies, the study included 16 cases of vulvar SCC [21].

Regarding the surgical indications, these were in accordance with the FIGO staging and were followed by an uneventful recovery in the long term, with the second patient requiring adjuvant radiotherapy after pathological restaging. The presented cases highlight the crucial role of the multidisciplinary oncology board, which should include a gynecologic oncologic surgeon, medical oncologist, radiotherapist, pathologist, radiologist, and other specialists as needed [22].

A 2020 study analyzing 1148 cases from a historical cohort of patients with high-grade VIN assessed the risk of progression to SCC based on multiple factors. The 10-year cumulative risk of vulvar cancer was 10.3%, influenced by the VIN subtype, presence of lichen sclerosus, and age at diagnosis. The absolute 3-year risk of progression to invasive carcinoma in HSIL cases was 5.7%. For dVIN lesions, the 14-year risk was significantly higher at 58%, though the patient cohort was small due to the diagnostic challenges associated with dVIN, particularly its differentiation from lichen sclerosus. Patients with dVIN exhibited a significantly higher risk of cancer and a shorter progression interval compared to those with HSIL, highlighting the aggressive nature of dVIN. Additional risk factors for progression to SCC include the presence of lichen sclerosus and advanced age [23].

HPV-associated vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCCs) typically exhibit basaloid or warty histology and develop from usual-type VIN. The viral proteins E6 and E7 contribute to malignant transformation by disrupting the function of p53 and the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene. On the other hand, HPV-independent VSCCs are predominantly keratinizing and are linked to differentiated VIN and lichen sclerosus. These tumors frequently harbor p53 mutations. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 (INK4a) and p53 can aid in distinguishing between HPV-driven and HPV-independent forms of VSCC. While further large-scale, multicenter studies are required to fully understand the role of HPV in VSCC prognosis, current evidence suggests no significant survival differences between the two subtypes [24].

Rakislova N et al. [25] examined 326 cases of DNA HPV-positive vulvar SCC, ensuring that each had at least 1 cm of surrounding skin for analysis. They conducted HPV typing, assessed HPV E6I mRNA expression, and performed p16 immunohistochemistry on all samples, alongside a detailed histopathological evaluation. Tumors were classified as definitively linked to HPV if they tested positive for p16 or HPV E6I mRNA, or both, in addition to the presence of HPV DNA. Cases that were negative for both markers were considered inconclusive regarding HPV association. Among the tumors studied, 121 (37.1%) had normal surrounding skin, 191 (58.6%) were associated with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (also referred to as usual-type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia), and 14 (4.3%) exhibited atypical intraepithelial changes. Of these, seven presented features resembling differentiated VIN (dVIN), five showed characteristics similar to lichen sclerosus (LS), and two exhibited a combination of both patterns. Six of these unusual cases were definitively linked to HPV (three with dVIN-like traits, two with LS-like changes, and one displaying both patterns). All six were associated with HPV16 and tested positive for both p16 and HPV mRNA, with p16 expression also observed in the dVIN-like and LS-like lesions. In conclusion, a small proportion of vulvar SCCs with confirmed HPV involvement may originate from intraepithelial lesions that closely resemble the precursors of HPV-independent tumors [25].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this case series underscores the critical role of early diagnosis in shaping the prognosis of vulvar neoplasms. Early diagnosis is key in any gynecological neoplastic pathology. Therefore, patients presenting even with minor vulvar symptoms should be investigated in a thorough manner, with HPV testing and targeted biopsy recommended in selected cases. Timely detection allows for the implementation of less radical yet oncologically effective surgical interventions, thereby reducing the extent of tissue resection while ensuring effective disease management. By adopting a more conservative yet strategically guided surgical approach, the balance between oncologic control and quality of life can be optimized. This highlights the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach in tailoring treatment strategies to each patient, ultimately improving both clinical outcomes and postoperative well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.D.B.; investigation, F.E.A.; resources, O.D.B. and C.B.; data curation, R.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.E.A. and O.D.B.; writing—review and editing, F.E.A. and O.D.B.; visualization, R.M.S.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, O.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Saint John Hospital (approval code: 2362 and date for the approval: 31 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patients involved in the case reports. The patients provided informed consent regarding the images and their publication, and the images do not contain any information that could lead to patient identification.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, J.; Chan, S.C.; Fung, Y.C.; Pang, W.S.; Mak, F.Y.; Lok, V.; Zhang, L.; Lin, X.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., 3rd; Xu, W.; et al. Global incidence, risk factors and trends of vulvar cancer: A country-based analysis of cancer registries. Int. J. Cancer. 2023, 153, 1734–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, N.; Rauh, L.A.; Lachiewicz, M.P.; Horowitz, I.R. Margins for cervical and vulvar cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 113, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tornesello, M.L. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and its prognostic value in vulvar cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.T.; Sand, F.L.; Albieri, V.; Norrild, B.; Kjaer, S.K.; Verdoodt, F. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in squamous cell carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, D.; Gomez-Martinez, R.A. Vulvar Cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 46, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, F.L.; Ten Eikelder, M.L.G.; Kapiteijn, E.H.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Galaal, K.; van Poelgeest, M.I.E. Vulvar malignant melanoma: Pathogenesis, clinical behaviour and management: Review of the literature. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 73, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, J.; Bogliatto, F.; Haefner, H.K.; Stockdale, C.K.; Preti, M.; Bohl, T.G.; Reutter, J. The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Terminology of Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2016, 20, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbritton, J.I. Vulvar Neoplasms, Benign and Malignant. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 44, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Ewing-Graham, P.C.; Swagemakers, S.M.; van der Spek, P.J.; van Doorn, H.C.; Hegt, V.N.; Koljenović, S.; van Kemenade, F.J. Precursor lesions of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma—Histology and biomarkers: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 147, 102866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlmuth, C.; Wohlmuth-Wieser, I. Vulvar malignancies: An interdisciplinary perspective. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. JDDG 2019, 17, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capria, A.; Tahir, N.; Fatehi, M. Vulvar Cancer; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, B.S.; Jensen, H.L.; Brule, A.J.v.D.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Frisch, M. Risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and vagina—Population-based case–control study in Denmark. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 2827–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, L.A.; Thistle, J.E.; Liao, L.M.; Trabert, B. Epidemiology of vulvar neoplasia in the NIH-AARP Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De San José, S.; Alemany, L.; Ordi, J.; Tous, S.; Alejo, M.; Bigby, S.M.; Joura, E.A.; Maldonado, P.; Laco, J.; Bravo, I.G.; et al. Worldwide human papillomavirus genotype attribution in over 2000 cases of intraepithelial and invasive lesions of the vulva. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 3450–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.P.; Miron, A.; Yassin, Y.; Monte, N.; Woo, T.Y.C.; Mehra, K.K.; Medeiros, F.; Crum, C.P. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia contains Tp53 mutations and is genetically linked to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, M.; Scurry, J.; Marchitelli, C.E.; Micheletti, L. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 28, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrão, P.G.; Guimarães, Y.M.; Godoy, L.R.; Possati-Resende, J.C.; Bovo, A.C.; Andrade, C.E.M.C.; Longatto-Filho, A.; dos Reis, R. Management of Early-Stage Vulvar Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Smith, M.; Barlow, E.; Coffey, K.; Hacker, N.; Canfell, K. Vulvar cancer in high-income countries: Increasing burden of disease. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2174–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.E.; Ghasemi, H.; Najafi, M.; Yekta, Z.; Nejadghaderi, S.A. Incidence Trends of Vulvar Cancer in the United States: A 20-Year Population-Based Study. Cancer Rep. 2024, 7, e2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.L.; Sand, F.L.; Hoffmann Frederiksen, M.; Kaae Andersen, K.; Kjaer, S.K. Does HPV status influence survival after vulvar cancer? Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.F.; Chen, J.; Huvila, J.; Pors, J.; Ren, H.; Ho, J.; Chow, C.; Ta, M.; Proctor, L.; McAlpine, J.N.; et al. p53 Immunohistochemical patterns in HPV-related neoplasms of the female lower genital tract can be mistaken for TP53 null or missense mutational patterns. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Yashar, C.M.; Arend, R.; Barber, E.; Bradley, K.; Brooks, R.; Campos, S.M.; Chino, J.; Chon, H.S.; Crispens, M.A.; et al. Vulvar Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuijs, N.B.; van Beurden, M.; Bruggink, A.H.; Steenbergen, R.D.M.; Berkhof, J.; Bleeker, M.C.G. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: Incidence and long-term risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pino, M.; Rodriguez-Carunchio, L.; Ordi, J. Pathways of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology 2013, 62, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakislova, N.; Alemany, L.; Clavero, O.; del Pino, M.; Saco, A.; Quirós, B.; Lloveras, B.; Alejo, M.; Halec, G.; Quint, W.; et al. Differentiated Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia-like and Lichen Sclerosus-like Lesions in HPV-associated Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Vulva. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 42, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the JMMS. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).