Abstract

Background/Aim: This case report navigates through the challenges of a complex clinical scenario involving germ cell tumors (GCTs), one of the most frequently encountered malignancies in adolescents and young adults. Case report: We present the case of an 18-year-old patient exhibiting atypical clinical manifestations, prompting emergent extensive surgical intervention. Upon admission to the Oncology Department, the adolescent presented with jaundice and dyspnea, being diagnosed with pure non-seminomatous embryonal carcinoma, a poor-risk prognosis group. Based on his prognostic group, the patient should have undergone chemotherapy with a well standardized regimen, but the imminent “liver visceral crisis” did not allow for the standard dose chemotherapy administration, so an adapted regimen of chemotherapy was considered and the full number of cycles was applied after this induction cycle. The treatment journey was protracted, emphasizing the need for early recognition and intervention in such cases. A comprehensive ongoing evaluation, including imagistic examinations and laboratory tests, revealed the presence of extensive refractory disease, which led to urgent treatment. Conclusions: This case provides valuable insights into the management of advanced testicular germ cell tumor in young patients facing imminent organ failure and underlines the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration. Understanding the complexities of this condition can aid in improving patient outcomes and enhancing the quality of care provided.

1. Introduction

Testicular cancer represents an important issue worldwide because it appears to be the predominant type of solid malignancy in young males (15–35 years) in the United States of America, and although the majority of patients are able to be cured by the effective treatments available, there are still young patients that eventually die due to this disease [1]. Worldwide, according to data published by Globocan, there are 75,000 new patients and 9000 deaths per year.

While the 5 year overall survival in good prognosis non-seminomatous testicular tumors exceeds 92% and is considered to be a curable condition, the survival at 5 years in poor prognosis non-seminomatous testicular cancer is below 67% [2]. The urgent need for a revolutionary approach is obvious, given the fact that this type of cancer affects young adults [3,4,5].

Patients usually present at an early stage of the disease when they observe a mass in the testicle or the enlargement of testicles that may be associated with lumbar or flank pain, scrotal discomfort or gynecomastia [6]. There is also a lower percentage of patients (less than 15%) that present with atypical symptoms determined by the presence of metastasis, such as the following: dyspnea, cough, anorexia, vomiting, gastrointestinal hemorrhages or bone pain. These patients, according to the literature, seem to have an adverse outcome with a higher death rate [7].

It is crucial to underscore that, regardless of the chosen treatment modality, the likelihood of achieving a complete cure in these patients remains below 50% [8,9,10,11]. In cases where individuals experience repeated treatment failures, recourse to palliative chemotherapy, consideration of “desperate surgery” or the provision of supportive care represent the only available options for management.

At present, a universally accepted treatment regimen does not exist for men who experience cancer progression following high-dose chemotherapy for advanced germ cell tumors (GCT). Rare instances of favorable responses have been documented with the utilization of different chemotherapy agents, such as gemcitabine, paclitaxel and oxaliplatin, whether administered individually or in various combinations. If any responses do occur, they typically exhibit a short duration [12,13].

The aim of this case report is to raise awareness of the atypical clinical presentation of germ cell tumors and the fact that sometimes we will have to use all the available systemic treatment options in the right sequence for some patients.

2. Case Report

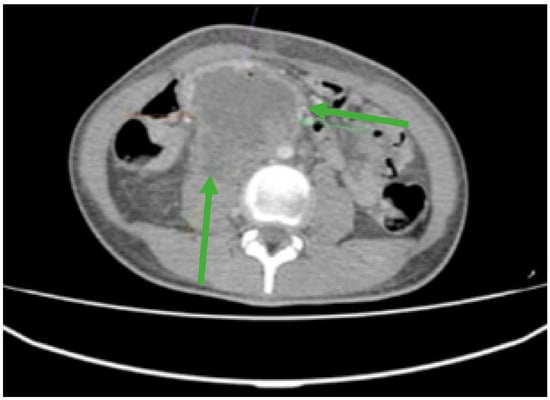

In this report, we will discuss the case of an 18-year-old male patient who presented with a complex set of symptoms, including melena, hematemesis, pallor, and severe fatigue. The patient’s symptoms were primarily attributed to gastrointestinal hemorrhage, specifically originating from a retroduodenal mass (Figure 1), which represented the primary cause for his urgent hospital admission. While testicular cancer can present with metastatic manifestations in around 10–12 percent of patients, it is still a very unusual presentation and difficult to be assessed by the clinicians.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed an irregular, slightly rounded retroperitoneal abdominal mass measuring 70 × 98 × 66 mm (green arrows).

Furthermore, laboratory investigations revealed severe anemia with a hemoglobin level as low as 4.2 g/dL. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the extent of the disease and its impact on the patient’s overall health, an extensive evaluation was conducted. This assessment included Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and whole-body computed tomography (CT). These diagnostic tests collectively confirmed the presence of an extended retroperitoneal mass (Figure 1), which had invaded the duodenum, thus underscoring the severity and complexity of the patient’s condition.

In this clinical scenario in which life threatening hemorrhage seemed imminent, it was considered that any additional investigations that would take even a few days would be detrimental for the patient. The multidisciplinary team decided that a surgical approach would be the first step to resolve the emergency and to establish a pathological diagnosis. The differential diagnosis considered were a retroperitoneal sarcoma, adenocarcinoma of the duodenum or a cholangiocarcinoma of the extrahepatic duct.

An emergency and complex surgical procedure was performed, consisting of an en bloc resection of multiples organs that encompassed the inferior infrarenal vena cava, segments II and III of the duodenum, pancreatic head and portions of the right lumbar ureter, followed by an uretero–ureteral anastomosis, wherein a ureteral stent was strategically placed.

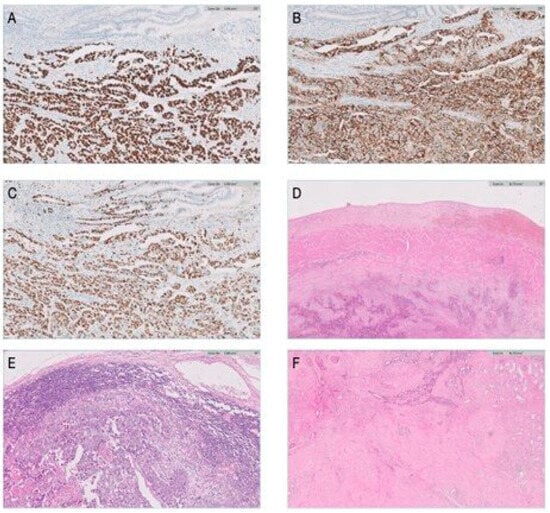

Subsequent to the surgical intervention, the retrieved tissue underwent rigorous histopathological and immunohistochemical examination (Figure 2A–E). These diagnostic techniques were instrumental in identifying the precise nature of the retroperitoneal tumor. The histopathology report identified cellular elements of syncytiothrophoblast. An immunohistochemistry report was mandatory to precisely identify the type of tumor.

Figure 2.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of the tissue specimen. (A) SALL 4 marker for germ cell tumors (100×)—positive at the level of the tumoral cells. (B) CD30-specific marker for embryonal carcinoma in germ cell tumors (100×)—positive at the level of the tumoral cells. (C) Extensive nuclear positivity in tumor cells for Ki67 (100×). (D) Tumoral invasion at the level of the inferior cava vein—hematoxilin–eosin, 20×. (E) Lymph node metastases—hematoxilin–eosin, 20×. (F) Overview image of testicular fibrosis—no tumor cells—hematoxilin–eosin, 20×.

The immunohistochemistry tests conclusively established the tumor as a pure embryonal testicular carcinoma. The positivity for SALL4 and OCT 4 sustain the germinal cell type origin. The intense positivity for CD30 confirms the pure embryonal carcinoma type.

The patient presented for an oncology consultation and a urological evaluation with testicular ultrasound was recommended.

The clinical assessment, complemented by a testicular ultrasound, unveiled the presence of a slightly discernable 1.5 cm diameter mass within the patient’s right testicle.

The patient was admitted to the Oncology Department for systemic chemotherapy and a progression of distressing symptoms emerged, including jaundice and dyspnea. Subsequent laboratory investigations demonstrated compelling evidence of cholestasis, marked by impaired bile flow, along with hyperbilirubinemia and hepatic cytolysis (Table 1). The hematology report indicates persistent severe anemia. In this clinical setting, it was decided to reevaluate the extension of the disease. The serum markers were very elevated with a beta HCG of 600,000 mIU/mL, which meant that this patient was included in the S3 category.

Table 1.

Laboratory tests suggesting liver failure.

The medical imaging, consisting of a comprehensive CT scan encompassing the thorax, abdomen and pelvis, revealed a multifocal presence of lung and liver metastases, characterized by multiple confluent lesions. Upon staging assessment, the diagnosis was established as non-seminomatous testicular cancer, categorized as cTxcN3 M1Hep, M1PulS3, designating stage group IIIC. This classification placed the patient in the IGCCCG (International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group) poor-risk prognosis group. The brain MRI revealed no brain metastasis.

In accordance with this prognostic classification, the recommended course of treatment for the patient entailed the administration of a complex five days chemotherapy regimen known as BEP, which combines bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin. If there is any contraindication for bleomycin, the recommended regimen is VIP (etoposid, ifosfamide and cisplatin), a five days chemotherapy regimen that carries a high risk of febrile neutropenia.

The impending “liver visceral crisis”, a term signifying a severe and rapidly deteriorating state of the liver, rendered the administration of standard-dose chemotherapy infeasible. In such a critical scenario, we were confronted with a pivotal decision. We were presented with two primary alternatives: the first being the best supportive care, which, in the context of an 18-year-old patient, was deemed an unacceptable option. The second alternative involved the utilization of a low-dose induction chemotherapy strategy, administered on a weekly dosing schedule (5). After careful consideration, we opted for the latter approach.

The chosen strategy involved initiating an adapted first cycle of chemotherapy, incorporating cisplatin and etoposide (cisplatin 20 mg/sqm, etoposide 100 mg/sqm z1–2, weekly) [5]. Following the completion of this induction cycle, it was determined that the full complement of chemotherapy cycles should be administered as the biological variables normalized. We observed an accelerated decrease in the serum beta HCG value and an improvement in the liver function and symptoms. Notably, orchidectomy was scheduled to be performed upon the conclusion of the first-line chemotherapy in the context of this emergency situation.

After the improvement of liver function laboratory tests and the disappearance of dyspnea, we decided to start the full dose first line chemotherapy. Subsequently, a strategic decision was made to administer VIP chemotherapy (ifosfamide 1200 mg/sqm, etoposide 75 mg/sqm, cisplatin 20 mg/sqm, day 1–5 q3W), not only because of the presence of multiple lung metastases and the possibility of lung surgery after chemotherapy, but also because of the decrease in carbon monoxide diffusion capacity that this treatment caused. Four cycles of VIP with growth factor support were administered to prevent febrile neutropenia and acceptable tolerance.

Upon the conclusion of the fourth cycle of VIP chemotherapy, a follow-up evaluation was conducted utilizing chest and abdomino-pelvic CT scans. This imaging assessment revealed a notable reduction in the size of the metastatic lesions. Afterwards, a PET-CT scan was to evaluate the metabolic activity of the hepatic metastasis. Remarkably, this advanced imaging technique depicted some low metabolic activity in only a few of the liver metastases, signifying a favorable response to the treatment. However, concomitant with imagistic response, we also observed a biological response normal value in the level of serum markers associated with the disease. Because it was impossible to detect the hepatic metastasis with metabolic activity intraoperatively, we decided to do a 3-month imagistic and biological follow-up of the patient.

Right orchidectomy was performed in October 2021. The surgical removal of the affected testicle is a necessary step in the therapeutic approach, as it eliminates the primary tumor burden. The histopathological showed there were no tumor cell remnants, only focal tissue microcalcifications, which suggests a past existence of an embryonal carcinoma component in a regressed testicular terminal cell tumor after chemotherapy treatment (Figure 2F).

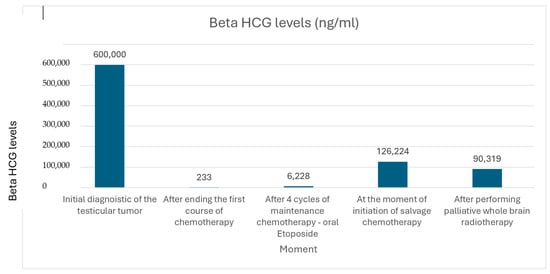

After six months, we observed the aggressive evolution of the disease by rapidly increasing markers, and in light of this understanding, a decision was promptly made to initiate high-dose chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the context of managing this relapsed case. Two cycles of high-dose etoposide 750 mg/sqm and carboplatin 700 mg/sqm (May 2022–June 2022) with stem cell support were administered, followed by four cycles of maintenance chemotherapy with oral etoposide 50 mg/sqm q3w (August 2022–November 2022). This intervention led to a slow decline in the levels of beta-hCG (233 mIU/mL), indicating a therapeutic response.

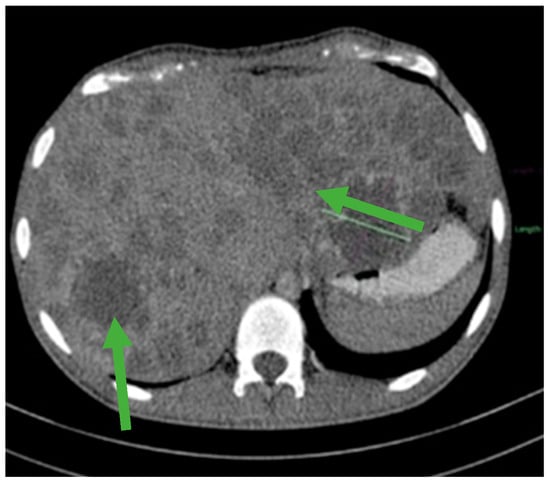

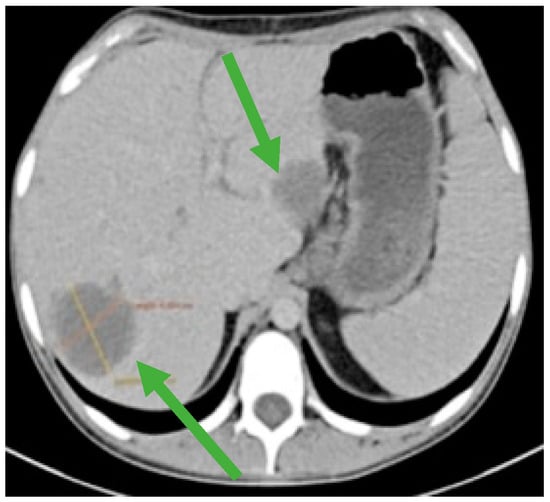

During the maintenance therapy with oral etoposide, the plasma beta HCG was highly increased (6228 mIU/mL), so we decided to start third line chemotherapy with GOP (gemcitabine 800 mg/sqm day 1 and 8, paclitaxel 80 mg/sqm day 1 and 8, oxaliplatin 130 mg day 1, q3w). After five cycles, we observed a new biological and imagistic progression (Figure 3 and Figure 4) in the size and number of the liver and lung metastases that appeared.

Figure 3.

Hepatomegaly and multiple liver metastases (green arrows).

Figure 4.

CT scan showing liver metastases in numerical and dimensional progression (green arrows).

The brain MRI showed no brain metastasis, although the patient reported two episodes of hallucination.

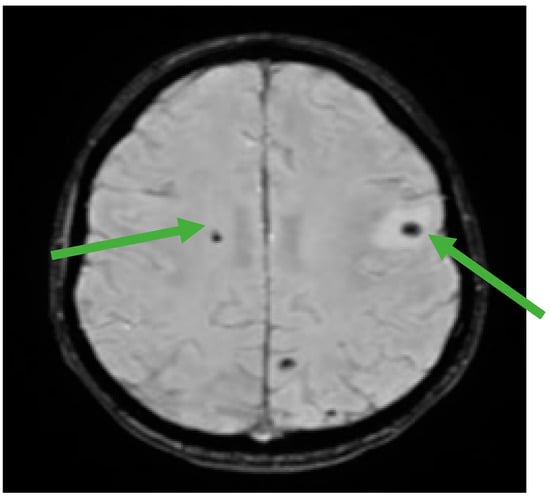

In the meantime, we monitored beta HCG and there were slightly increased values, but when the beta HCG was at 126,224 mIU/mL, we established the progression of the disease. Although it was not a standard treatment and there was a low chance to have a responsive disease in the fourth line setting, the fact that it was a young patient with a good performance status influenced our decision to start salvage chemotherapy with cisplatin–epirubicin regimen for four cycles (epirubicin 90 mg/sqm day 1, cisplatin 20 mg/sqm day1–5 qw3). After the fourth cycle, the patient started to have recurrent seizures and a new brain MRI showed multiple hemorrhagic supratentorial and cerebellar metastasis on both sides of the brain. Palliative whole brain radiotherapy was immediately initiated, improving the patient’s condition I, Figure 5. Unfortunately, the patient seems to continue to progress with an increased beta HCG of 90,319 mIU/mL (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Brain MRI showing multiple hemorrhagic metastases at the supratentorial and cerebellar level (green arrows).

Figure 6.

Evolution of Beta HCG levels during treatment.

Through the clinical evaluation and multiples lines of chemotherapy, the patient has received psychological counseling and emotional support from their family and the medical team involved in managing this case.

The patient is still alive and continues to be closely monitored. Despite experiencing multiple relapses and undergoing all available lines of evidence-based treatment, he has remained under the care of our multidisciplinary team. His case illustrates the protracted and challenging course that such aggressive tumors can take, as well as the importance of continuous medical, psychological, and supportive care throughout the disease trajectory.

3. Discussion

This case highlights several crucial aspects in the management of testicular germ cell tumors (GCTs), particularly in young patients presenting with atypical symptoms and aggressive disease biology.

One of the major learning points is the importance of considering GCTs in the differential diagnosis of young male patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia or retroperitoneal masses. Although gastrointestinal metastases from testicular cancer are rare, they have been described in the literature as most commonly involving the duodenum, often due to retroperitoneal lymph node invasion [14,15,16,17,18]. These unusual presentations can lead to emergency surgical admissions where expertise in testicular cancer may be lacking, resulting in diagnostic delays and suboptimal early management.

In our case, the patient presented with severe anemia and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and was initially evaluated as having retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma, duodenal adenocarcinoma, or cholangiocarcinoma. Due to the life-threatening hemorrhage, biopsy was not feasible prior to surgical intervention. This highlights the difficulty of achieving a timely histological diagnosis in emergency contexts and underscores the importance of institutional readiness to consider GCTs as part of the diagnostic algorithm in young men with retroperitoneal masses.

Although the disease was diagnosed at an advanced stage, the patient had no significant medical history and did not report any prior testicular symptoms. At only 18 years old, with limited medical education and burdened by feelings of embarrassment typical for adolescents, the patient was unaware of the importance of testicular self-examination and did not recognize the slowly growing testicular mass. Embarrassment and reluctance to discuss intimate health concerns likely contributed to the delay in seeking medical attention, allowing the tumor to progress silently until the onset of severe visceral metastatic symptoms. In the absence of early symptoms and clinical suspicion, the diagnosis was ultimately made in an emergency oncological context. Fortunately, the lack of comorbidities allowed for the consideration of an intensive treatment strategy once the patient was stabilized.

Chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment for metastatic non-seminomatous GCTs, as outlined in ESMO and NCCN guidelines [2,11,15,16,17,18,19]. However, patients with poor-risk features—especially those presenting in visceral crisis—pose unique therapeutic challenges. The rapid onset of symptoms and multi-organ involvement may preclude standard-dose chemotherapy due to poor performance status and organ dysfunction [6,7,14].

In such cases, dose-adapted induction regimens have proven to be effective. Our initial use of a modified etoposide–cisplatin (EP) schedule was based on emerging evidence, such as the protocol adopted by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, which showed the efficacy and tolerability of low-dose weekly EP in similar high-risk patients [14]. After stabilization, we were able to escalate to a full VIP regimen, avoiding bleomycin due to compromised pulmonary function. This personalized treatment approach, guided by clinical parameters, biomarker kinetics, and imaging, reflects the adaptability required in high-risk cases.

While both BEP and VIP regimens are validated for first-line therapy in poor-risk patients, our choice of VIP was also supported by evidence from Intergroup Trial E3887, which reported comparable survival outcomes [20,21]. Despite achieving radiologic and serologic response initially, the patient demonstrated early relapse, reflecting the aggressive nature of the disease.

Second- and third-line treatment decisions in relapsed GCTs remain complex. Current ESMO guidelines recommend conventional-dose TIP or high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with autologous stem cell support [22,23]. Given the early relapse after first-line cisplatin-based therapy and the high tumor burden, we proceeded with HDCT, although the response was limited. Ultimately, the patient underwent multiple salvage regimens including oral etoposide maintenance, gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, a paclitaxel regimen and cisplatin–epirubicin, reflecting a short duration of the response in successive lines of treatment.

This case also raises important considerations regarding the timing of orchidectomy. In patients with extensive visceral disease, immediate systemic therapy is often prioritized. ESMO guidelines support deferring orchiectomy in such settings [21]. In our patient, the procedure was safely postponed until systemic disease was controlled, and post-chemotherapy histology was negative for residual malignancy.

Despite exhaustive multimodal therapy and adherence to evidence-based guidelines, the patient ultimately progressed, illustrating the limitations of current treatments in highly aggressive GCTs and underscoring the urgent need for novel therapies and inclusion in clinical trials—particularly in countries where access to trials is limited [24,25,26,27,28,29].

Psychosocial support and clear patient–physician communication played an essential role throughout this challenging clinical course. A strong therapeutic alliance helped ensure treatment adherence and supported the patient’s mental well-being amidst a protracted and emotionally taxing disease journey [30,31].

4. Conclusions

This clinical case reveals the fact that sometimes managing testicular germ cell tumors can be challenging both for diagnosis and treatment. Having the expertise to choose the right diagnostic tools and starting the systemic treatment with the right regimen, although the patient developed a “liver visceral crisis”, is crucial for atypical presentation cases.

Ultimately, we must also be aware of the psychological support that we must offer for young patients and their caregivers, an attitude that could assure more treatment compliance and better tolerance regarding toxicities and their impact on quality of life.

Author Contributions

I.P. and A.-M.S. provided patient information and wrote the manuscript. I.P., N.B. and A.-M.S. collected the data, C.S. and F.A. prepared histopathological examination and illustrations, L.N.G. and I.B. (Iulian Brezean) consulted the treatment plan. I.P., I.B. (Irina Balescu) and A.-M.S. reviewed the topic presentation, structure of the manuscript, illustrations and photographs. C.B. contributed to the conception and design of the study and reviewed and edited the writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Informed Consent Statement

The patient who participated in the study provided written informed consent for the publication of any associated data.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available at reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

The Editorial Office and Editorial Board have concluded the post-publication review process for this publication. Following concerns raised about a potential conflict of interest in the editorial decision making, the Editorial Office conducted a post-publication peer-review of this article. This process included the recruitment of an Editorial Board Member to ensure full compliance with MDPI’s Editorial Process (https://www.mdpi.com/editorial_process). With this update, the Academic Editor is satisfied that the editorial process for this article has been completed in accordance with MDPI’s Editorial Process policy.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenburg, J.; Fosså, S.D.; Nuver, J.; Heidenreich, A.; Schmoll, H.J.; Bokemeyer, C.; Horwich, A.; Beyer, J.; Kataja, V.; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Testicular seminoma and non-seminoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, vi125-32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, D.J.; Gleeson, J.P.; Feldman, D.R. Testicular cancer in 2023: Current status and recent progress. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 115–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Ali, A. Urologic Cancers (Internet); Exon Publications: Brisbane, AU, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER). Cancer Stat Facts: Testicular Cancer; National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Germà-Lluch, J.R.; Garcia del Muro, X.; Maroto, P.; Paz-Ares, L.; Arranz, J.A.; Gumà, J.; Alba, E.; Sastre, J.; Aparicio, J.; Fernández, A.; et al. Clinical pattern and therapeutic results achieved in 1490 patients with germ-cell tumours of the testis: The experience of the Spanish Germ-Cell Cancer Group (GG). Eur. Urol. 2002, 42, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann, K.P.; Krain, J.; Gottschalk, W.; Büttner, P. Atypische Symptomatik bei Patienten mit germinalen Hodentumoren (Atypical symptoms in patients with germinal testicular tumors). Urologe A 1994, 33, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, J.; Elghiaty, A.; Ham, W.S. Recent global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Medicine 2018, 97, e12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasdev, N.; Moon, A.; Thorpe, A.C. Classification, epidemiology andtherapies for testicular germ cell tumours. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2013, 57, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Weiner, A.; Zack, T.; O’Donnell, E.; Guerriero, J.L.; Bernard, B.; Reddy, A.; Han, G.C.; AlDubayan, S.; Amin-Mansour, A.; Schumacher, S.E.; et al. Genomic evolution and chemoresistance in germ-cell tumours. Nature 2016, 540, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C.; Dinh, P.C.; Fossa, S.D.; Travis, L.B. Testicular Cancer Survivorship. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokemeyer, C.; Hartmann, J.T.; Kuczyk, M.A.; Truss, M.C.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Beyer, J.; Jonas, U.; Kanz, L. Recent strategies for the use of paclitaxel in the treatment of urological malignancies. World J. Urol. 1998, 16, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, E.M.; Muggia, F.M.; Rozencweig, M. Chemotherapy of testicular cancer: From palliation to curative adjuvant therapy. Semin. Oncol. 1979, 6, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chan Wah Hak, C.; Coyle, C.; Kocache, A.; Short, D.; Sarwar, N.; Seckl, M.J.; Gonzalez, M.A. Emergency Etoposide-Cisplatin (Em-EP) for patients with germ cell tumours (GCT) and trophoblastic neoplasia (TN). BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbright, T.M.; Loehrer, P.J. Choriocarcinoma-like lesions in patients with testicular germ cell tumors. Two histologic variants. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1998, 12, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malbari, F.; Gershon, T.R.; Garvin, J.H.; Allen, J.C.; Khakoo, Y.; Levy, A.S.; Dunkel, I.J. Psychiatric manifestations as initial presentation for pediatric CNS germ cell tumors, a case series. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2016, 32, 1359–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emre Duygulu, M.; Kaymazli, M.; Goren, I.; Yildirim, B.; Sullu, Y.; Nural, M.S.; Bektas, A. Embryonal Testicular Cancer with Duodenal Metastasis: Could Nausea and Vomiting be Alarm Symptoms? Euroasian J. Hepatogastroenterol. 2016, 6, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ani, A.H.; Al Ani, H.A. Testicular seminoma metastasis to duodenum. Misdiagnosed as primary duodenal tumor. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016, 25, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Testicular Cancer, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Available online: https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/17/12/article-p1529.xml (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Hinton, S.; Catalano, P.J.; Einhorn, L.H.; Nichols, C.R.; David Crawford, E.; Vogelzang, N.; Trump, D.; Loehrer, P.J., Sr. Cisplatin, etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in the treatment of disseminated germ cell tumors: Final analysis of an intergroup trial. Cancer 2003, 97, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honecker, F.; Aparicio, J.; Berney, D.; Beyer, J.; Bokemeyer, C.; Cathomas, R.; Clarke, N.; Cohn-Cedermark, G.; Daugaard, G.; Dieckmann, K.P.; et al. ESMO Consensus Conference on testicular germ cell cancer: Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1658–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, J.; Berney, D.M.; Bokemeyer, C.; Climent, M.A.; Daugaard, G.; Gietema, J.A.; De Giorgi, U.; Haugnes, H.S.; Huddart, R.A.; Leão, R.; et al. Testicular seminoma and non-seminoma: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, A.; Bascoul-Mollevi, C.; Kramar, A.; Einhorn, L.; Necchi, A.; Massard, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Fléchon, A.; Margolin, K.; Lotz, J.P.; et al. Conventional-dose versus high-dose chemotherapy as first salvage treatment in male patients with metastatic germ cell tumors: Evidence from a large international database. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2178–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, A.; Beyer, J.; Bascoul-Mollevi, C.; Kramar, A.; Einhorn, L.H.; Necchi, A.; Massard, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Fléchon, A.; Margolin, K.A.; et al. Prognostic factors in patients with metastatic germ cell tumors who experienced treatment failure with cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4906–4911. [Google Scholar]

- Bedano, P.M.; Brames, M.J.; Williams, S.D.; Juliar, B.E.; Einhorn, L.H. Phase II Study of Cisplatin Plus Epirubicin Salvage Chemotherapy in Refractory Germ Cell Tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5403–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajpert-De Meyts, E.; Skotheim, R.I. Complex Polygenic Nature of Testicular Germ Cell Cancer Suggests Multifactorial Aetiology. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagrodia, A.; Pierorazio, P.; Singla, N.; Albers, P. The Complex and Nuanced Care for Early-stage Testicular Cancer: Lessons from the European Association of Urology and American Urological Association Testis Cancer Guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2020, 77, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, T.; Schmelz, H.; Müller, A.C.; Seidel, C. Multimodale Therapie des Hodentumors: Wann Chemotherapie, Operation oder Strahlentherapie? (Multimodal treatment of testicular cancer: Chemotherapy, surgery or radiotherapy?). Urologie 2022, 61, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas-Plaza, X.; de Vries, G.; Meersma, G.J.; Suurmeijer, A.J.; Gietema, J.A.; van Vugt, M.A.; de Jong, S. Dual mTORC1/2 Inhibition Sensitizes Testicular Cancer Models to Cisplatin Treatment. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrady, M.E.; Willard, V.W.; Williams, A.M.; Brinkman, T.M. Psychological Outcomes in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiberg, M.; Bandak, M.; Lauritsen, J.; Andersen, K.K.; Skøtt, J.W.; Johansen, C.; Agerbaek, M.; Holm, N.V.; Lau, C.J.; Daugaard, G. Psychological stress in long-term testicular cancer survivors: A Danish nationwide cohort study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).