1. Introduction

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) is a chronic, late-onset manifestation of Lyme borreliosis that predominantly affects the distal extremities. It is characterized by progressive thinning and atrophy of the skin. Unlike other dermatologic manifestations of Lyme disease, such as erythema migrans or borrelial lymphocytoma, ACA does not resolve spontaneously and requires medical intervention. If left untreated, it evolves from an initial bluish-red discoloration and inflammation to marked skin atrophy and fibrosis, which are significantly more resistant to treatment in advanced stages. Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical presentation, serologic testing, and histopathologic examination. However, due to its insidious onset and nonspecific early symptoms, ACA remains challenging to recognize and diagnose in its initial stages [

1,

2]. The pathogenesis of ACA is primarily driven by a chronic T-cell-mediated immune response to

Borrelia spirochetes within the dermis. These bacteria exhibit a strong affinity for collagen fibers and extracellular matrix proteins, such as glycosaminoglycans and fibronectin. This interaction activates metalloproteinases that degrade the extracellular matrix, resulting in the destruction of collagen and the subsequent development of fibrosis and skin atrophy. The persistent immune response, coupled with progressive connective tissue damage, underpins the characteristic chronic atrophy observed in ACA [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Lyme borreliosis, caused by the spirochete

Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted through the bite of Ixodes ticks, is a common vector-borne illness in Europe. The disease progresses through three distinct dermatologic stages: erythema migrans (stage 1), marked by the characteristic bull’s-eye rash; borrelial lymphocytoma (stage 2), often accompanied by neurological and cardiac complications; and late-stage manifestations, which in Europe typically include ACA (stage 3), while in North America, arthritis is more prevalent. ACA is primarily associated with

Borrelia afzelii but can also be linked to European strains of

B. burgdorferi and

B. garinii. It is more commonly observed in Europe, affecting approximately 10% of patients with Lyme disease, particularly women aged 40 to 70 years, whereas it remains rare in the USA and among pediatric cases [

7,

8,

9,

10].

The skin is the most commonly affected organ in Lyme borreliosis, with its dermatologic manifestations collectively referred to as “dermatoborreliosis”. The hallmark lesion of Lyme disease, erythema migrans (EM), appears at the site of a tick bite within 1 to 3 weeks in approximately 80% of patients. Typically, this lesion presents as an expanding erythematous patch with central clearing, often resembling a bull’s-eye. Although erythema migrans (EM) is often described as a bull’s eye rash, this so-called ‘classic’ presentation is not the only possible one. Rashes associated with Lyme disease can exhibit a wide range of clinical presentations. Atypical EM lesions reported in the literature include vesicles, erythematous papules, purpura, and lymphangitic streaks, which may lead to diagnostic uncertainty, especially in non-endemic regions. In untreated cases, the lesion may expand along collagen fibers, and secondary lesions may emerge at distant sites, indicating systemic spread. These secondary lesions generally resolve spontaneously over time. The differential diagnosis for EM includes conditions such as tinea corporis, urticaria, and erythema multiforme [

7].

Borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a less common manifestation, typically appearing 30 to 45 days after tick exposure. It presents as a solitary bluish-red plaque or nodule, often located on the earlobe or nipple. BL is characterized by a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, and lesions typically resolve with antibiotic therapy within 3 weeks [

7,

11].

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA), a late-stage manifestation of Lyme borreliosis, typically appears months to years after the initial infection, primarily affecting elderly individuals. ACA commonly manifests on the distal extremities, often on extensor surfaces or bony prominences. The condition progresses through an inflammatory phase marked by ill-defined bluish-red patches that later evolve into fibrotic plaques and atrophic skin. As the disease advances, the affected skin becomes thin, translucent, and prone to ulceration, with the potential for associated peripheral neuropathy. Histopathologically, ACA is characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells, along with collagen degradation and mucinous deposition in the early stages. In the atrophic phase, epidermal thinning, dilated blood vessels, and a lymphocytic–plasma cell infiltrate are observed. Notably,

Borrelia spp. can be cultured from ACA lesions even up to 10 years after their onset [

7,

12].

Atypical cutaneous manifestations of Lyme borreliosis include sclerodermatous lesions, morphea, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA), and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), among others. These conditions have been linked to

Borrelia burgdorferi through clinical and histological similarities with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA), serological evidence, the identification of

Borrelia in tissue samples, and positive responses to antimicrobial therapy. Studies have detected

Borrelia DNA in skin biopsies of patients with morphea and LSA, supporting its potential role in disease pathogenesis. Additionally, CBCL has been associated with

Borrelia, with evidence of

Borrelia-specific DNA in lesional biopsies and reports of its isolation from primary CBCL cases. Other dermatological conditions, including eosinophilic fasciitis, Jessner–Kanof syndrome, granuloma annulare, erythema multiforme, and urticarial vasculitis, have also been reported in association with

Borrelia infection. While further research is necessary to establish definitive causative links, current evidence suggests that

B. burgdorferi may contribute to the development of these dermatological disorders [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

In terms of systemic complications, Lyme borreliosis progresses through three stages, resembling syphilis, with intermittent latency. The primary stage presents as erythema migrans at the tick bite site, while the secondary stage involves disseminated skin lesions, meningitis, cranial neuropathies, atrioventricular blocks, and myocarditis. The tertiary stage is marked by acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) and neurological deficits such as radiculopathy and cognitive impairment. Additionally, more severe central nervous system involvement may occur, including chronic encephalitis and encephalopathy. These manifestations have been associated with the direct invasion of

Borrelia burgdorferi into CNS tissue, as evidenced by PCR and culture-based studies. Pathological findings such as perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, demyelination, vasculitis, and microglial activation have also been documented, suggesting a multifactorial pathogenesis involving both direct infection and immune-mediated mechanisms [

7,

18,

19]. Joint involvement is common throughout the disease. Arthralgias affect one-third of early-stage patients, while later stages manifest as intermittent migratory arthritis or oligoarthritis, which may progress to persistent deforming arthritis. Chronic borreliosis, though debated, is characterized by prolonged infection requiring extended antibiotic therapy, with neurological symptoms, arthritis, and skin lesions being predominant. Neuropsychiatric effects range from cognitive decline and memory loss to severe mood disorders and psychosis, significantly impacting quality of life. Though uncommon, Lyme borreliosis should be considered in patients presenting with classic skin lesions and relevant exposure history. Awareness of its broad differential diagnosis is crucial, particularly in endemic regions [

18].

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is primarily based on clinical findings, a history of tick exposure, and serological testing. Routine laboratory tests usually yield unremarkable results. According to the CDC, a confirmed diagnosis is established through the presence of erythema migrans, accompanied by either documented exposure or laboratory evidence of infection. In cases of late manifestations, serologic confirmation is required. The diagnostic process typically involves a two-step serologic approach: initial screening with ELISA or IFA, followed by confirmation through Western blot. PCR and culture of skin biopsy specimens offer higher sensitivity and specificity, especially in atypical presentations, though their use is typically limited to these cases. It is important to note that serological testing may yield false negatives in the early stages of the disease and false positives in conditions such as mononucleosis or autoimmune disorders, highlighting the critical need for clinical correlation [

7,

20].

Early therapy is most effective for Lyme disease, particularly for erythema migrans (EM), with doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 14–21 days) being the first-line treatment. For acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA), a longer 3–4-week course of antibiotics is recommended. In persistent ACA cases, or in patients with severe manifestations, IV ceftriaxone or penicillin G may be necessary. Alternatives include azithromycin, amoxicillin, and cefuroxime [

20].

2. Case Presentation

We present the case of a 48-year-old female who presented to our clinic in June 2024 with multiple erythemato-violaceous patches on her left lower leg, which had persisted for two years. She had a history of stage 3 pulmonary sarcoidosis, diagnosed in 2020 through CT scan and bronchoalveolar lavage, and was treated with a methylprednisolone regimen from July 2020 to January 2022. At the time of presentation, she was not on any medications, and her pulmonary sarcoidosis was stable. She reported no known allergies, maintained a normal BMI, and denied any history of erythema migrans or tick bites.

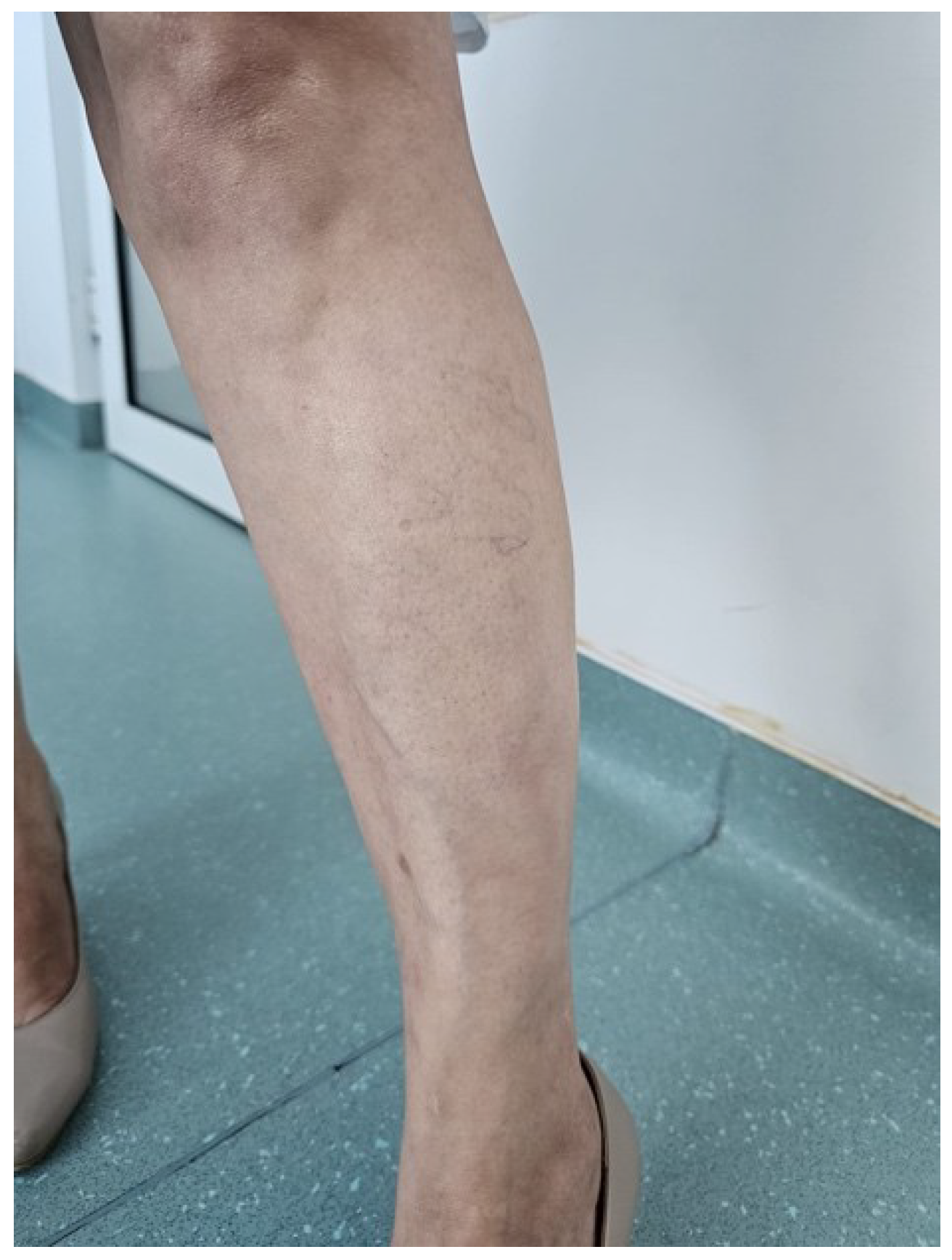

On examination, the patient presented with diffuse, poorly demarcated erythemato-violaceous patches on the left lower leg, involving both the anterior and posterior aspects. The lesions, measuring between 2 and 6 cm in diameter, were noted to be slightly warmer than the surrounding skin and exhibited subtle atrophy compared to unaffected areas (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). No nodules, edema, or other cutaneous abnormalities were observed. The patient reported intermittent burning sensations localized to the patches but denied any other systemic symptoms. The right lower extremity appeared unaffected.

The differential diagnosis, based on the patient’s clinical presentation and medical history, included cutaneous sarcoidosis, erythema nodosum, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA), venous insufficiency, and systemic sclerosis. A skin punch biopsy was performed on one lateral lesion, and histopathological examination revealed a superficial dermal infiltrate of small lymphocytes and numerous plasma cells, predominantly localized perivascularly and interstitially within thickened collagen fibers, with an intact epidermis. Immunohistochemistry investigations were conducted and demonstrated a reactive lymphocytic infiltrate, consistent with ACA. Borrelia serology via Western blot was positive for both IgG (31 bands) and IgM (8 bands), confirming the diagnosis of ACA in its inflammatory phase. Extensive blood tests revealed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP).

The patient was prescribed a 30-day course of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, along with topical emollients and mild corticosteroids for lesion management. She was also advised to make lifestyle modifications, such as avoiding local trauma, prolonged standing, and exposure to high temperatures. Consultations with neurology, rheumatology, and infectious diseases specialists were recommended. The patient experienced the complete resolution of skin lesions without adverse effects at the end of the treatment (

Figure 3). The neurological and rheumatological assessments were unremarkable. Given the early intervention during the inflammatory phase, the long-term prognosis is favorable, with a low risk of recurrence.

3. Discussions

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) is a rare, late-stage manifestation of Lyme borreliosis that presents with a range of clinical signs, often subtle and varied.

Our patient, presenting with clinical features consistent with ACA, exhibited poorly demarcated erythemato-violaceous patches on the left lower leg, characteristic of the early inflammatory phase of ACA. These lesions, ranging from 2 to 6 cm in diameter, were accompanied by subtle atrophy and mild warmth compared to the surrounding unaffected skin. This presentation aligns with the initial phase of ACA, where bluish-red lesions emerge on swollen, doughy skin. ACA commonly affects the unilateral extensor surfaces of the limbs, which is consistent with our patient’s clinical presentation, with lesions primarily localized to the left lower leg, while the right leg remained unaffected [

20,

21].

In terms of systemic symptoms, our patient did not report any general signs or symptoms, which is consistent with the early stages of ACA. Peripheral neuropathy is present in approximately 50% of ACA cases, typically manifesting as numbness, tingling, or allodynia. While neuropathic symptoms are a hallmark of the disease in its later stages, our patient did not experience any such symptoms, further suggesting that the condition was still in its early inflammatory phase. The absence of neuropathy at this stage may indicate either that the disease is in its initial phase, before neurological involvement has developed, or that the presentation is less typical [

21,

22].

Furthermore, a localized increase in collagen production, leading to band-like induration, which can restrict joint movement, has been reported in 15% of ACA patients. Although this feature was absent in our patient, the subtle atrophy observed in the affected areas of the left lower leg may represent the early stages of connective tissue remodeling, potentially progressing to more significant fibrotic changes over time. The development of fibrous nodules and joint induration, typically seen in advanced ACA, was also not present in this case, further supporting the idea that our patient presented during the early, less severe phase of the disease [

23].

The combination of findings in our patient—early inflammatory lesions without extensive skin atrophy or fibrotic changes, absence of peripheral neuropathy, and unilateral involvement—aligns with the early phase of ACA, as described in the literature, though it deviates in certain respects. A key challenge in diagnosing ACA is that many patients cannot recall being bitten by a tick or experiencing erythema migrans, complicating the connection to Lyme disease. Our patient was no exception, as she did not recall a tick bite, which further delayed the diagnostic process. Additionally, the absence of systemic symptoms and neuropathy, which are typically more prominent in later stages, made the early identification of ACA more difficult. These deviations highlight the clinical variability of ACA and underscore the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis, especially in endemic regions where patients may not recognize the early signs or associate them with prior tick exposure [

21].

In terms of differential diagnosis, the presented case underscores the diagnostic challenges in distinguishing acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) from other dermatologic and vascular conditions, as highlighted in the literature. The erythemato-violaceous lesions observed on the patient’s lower extremity initially led to a diagnosis of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), which is a common misdiagnosis in ACA due to the similar appearance of the lesions, including erythema, atrophy, and warmth of the skin. This misdiagnosis aligns with the findings in the literature, where CVI is often considered in the differential diagnosis of ACA lesions on the lower extremities. Additionally, other conditions such as superficial thrombophlebitis, lymphoedema, cold injuries, and vascular insufficiencies were also considered due to the overlap in clinical presentation [

2,

21].

Several dermatologic conditions that present with sclerotic lesions similar to those observed in ACA are also highlighted in the literature. Among them are morphea and lichen sclerosus, which were included in our differential diagnosis, particularly due to the presence of subtle atrophy and the lack of nodules in the patient’s presentation. Additionally, erysipelas and granuloma annulare, both of which can exhibit erythematous and raised lesions, are also mentioned as conditions that may be confused with ACA. Systemic sclerosis, with its characteristic sclerotic features, was similarly considered in our differential diagnosis. These conditions share overlapping clinical presentations with ACA, which further emphasizes the importance of an accurate diagnostic evaluation [

9,

21].

In our case, the correct diagnosis was ultimately established through a combination of skin biopsy and serological tests, as suggested in the literature. The biopsy revealed a superficial dermal infiltrate with small lymphocytes and plasma cells, which is consistent with ACA, and helped to differentiate it from other conditions such as morphea or systemic sclerosis. Furthermore, the positive Borrelia serology confirmed the diagnosis of ACA, a critical step in establishing the diagnosis of Lyme disease-related skin changes. Thus, both the biopsy and serological findings were crucial in correctly diagnosing ACA and ruling out other potential conditions that had initially been considered in the differential diagnosis.

Although the serological diagnosis using Western blot provided strong evidence supporting the diagnosis of ACA in its inflammatory phase (positive IgG with 31 bands and IgM with 8 bands), it is crucial to acknowledge and address the limitations inherent to these methods. Western blot, despite its high specificity compared to ELISA, is not devoid of challenges, particularly those related to cross-reactivity and interpretative subjectivity.

Several infectious agents and conditions can cause cross-reactions with

Borrelia burgdorferi antigens, potentially leading to false-positive results. Notably, antibodies elicited by

Treponema pallidum,

Anaplasma phagocytophilum,

Yersinia spp.,

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV),

Cytomegalovirus (CMV),

Parvovirus B19, and even autoimmune markers such as rheumatoid factor (RF) have shown reactivity with common

Borrelia antigens like OspC, FlaB, BmpA, and VlsE. These interactions are particularly problematic in the IgM class, where nonspecific responses are more common due to the immature nature of early immune responses [

24].

Moreover, the endemic prevalence of

B. burgdorferi s.l. antibodies, especially in high-risk European populations, further complicates the interpretation, as positive serology does not necessarily indicate active infection. It is also notable that patients may retain specific IgG (and in some cases IgM) antibodies for years post-infection, which can mislead clinicians when diagnosing late manifestations such as ACA [

24].

In this context, it is important that positive serologic findings are interpreted in conjunction with clinical presentation and epidemiologic exposure. A thorough differential diagnosis is necessary, especially in patients with nonspecific symptoms or atypical manifestations.

Our patient was prescribed a 30-day course of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, which aligns with the findings from studies such as Wormser et al., who demonstrated that a 28-day course of doxycycline is highly effective in treating ACA, with success rates of 85–100% [

25]. This study, along with others, supports doxycycline as the first-line therapy for ACA due to its proven efficacy in clearing the infection in the early stages. Alternatively, standard management also includes 14- to 28-day courses of other antibiotics, such as oral amoxicillin (500–1000 mg three times daily), intravenous ceftriaxone (2000 mg every 24 h), intravenous cefotaxime (2000 mg every 8 h), and intravenous penicillin G (3–4 MU every 4 h) [

26,

27]. In our case, the patient experienced the complete resolution of skin lesions by the end of the treatment. Additionally, the patient received adjunctive therapy with topical emollients and mild corticosteroids, which is a common approach to managing skin lesions. This method is also mentioned by Wormser et al., who noted that while antibiotics are crucial, supportive care with emollients helps to manage skin dryness and discomfort [

25].

In our patient’s case, neurological involvement was ruled out following a neurological evaluation, which found no clinical or paraclinical signs suggestive of neuroborreliosis. However, had there been evidence of central nervous system involvement, the treatment options would have needed to be adjusted accordingly. Although the optimal therapy for neuroborreliosis remains undefined, some studies suggest that higher doses of doxycycline—such as 200 mg twice daily (400 mg/day)—may be more effective than the standard 100 mg twice daily regimen. This is due to doxycycline’s superior penetration of the blood–brain barrier and greater efficacy against

Borrelia burgdorferi compared to penicillin G. Oral doxycycline also offers the advantage of outpatient treatment, even in more severe cases [

28].

Overall, the patient’s positive response to treatment and the lack of long-term complications aligns with recent findings that early, appropriate treatment significantly improves prognosis in ACA cases. Nevertheless, considering the potential for relapse or the emergence of delayed cutaneous or systemic manifestations, the patient remains under ongoing outpatient follow-up, both dermatologically and neurologically [

2].

4. Conclusions

This case underscores the critical importance of considering acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with chronic, atypical skin lesions. Although ACA is often overlooked due to its rarity and sometimes subtle manifestations, dermatologists must remain vigilant, especially in cases that deviate from more common dermatologic conditions. In these instances, skin biopsies are invaluable in clarifying diagnoses when the clinical presentation is ambiguous or does not fully align with typical patterns. Histopathological examination is essential for confirming the diagnosis, as it can distinguish ACA from other conditions with similar presentations, such as morphea or systemic sclerosis.

Early recognition and prompt antibiotic treatment, particularly with doxycycline, are paramount in preventing disease progression and avoiding irreversible complications like skin atrophy and neuropathy. Delayed treatment, on the other hand, can lead to more severe and persistent sequelae, including debilitating neurological complications such as meningoradiculitis, cognitive impairments, chronic pain, and sensory disturbances. In more severe cases, patients may suffer irreversible neuropathy and other chronic neurological sequelae, which can significantly impact their quality of life. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial in managing ACA, with pathologists providing valuable insights through biopsy results and infectious disease specialists guiding treatment protocols based on the patient’s clinical context and serological findings.

Through this case, we aim to raise awareness of ACA, emphasizing the importance of histopathological confirmation to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. While rare, diseases like ACA should never be dismissed, as early and precise intervention can significantly improve patient outcomes and reduce long-term morbidity. This case serves as a reminder of the vital roles thorough clinical evaluation and collaboration between specialties play in optimizing patient care and preventing misdiagnosis.