1. Introduction

Nasogastric (NG) tubes are frequently inserted into patients with dysphagia or those who are endotracheally intubated. An NG tube is inserted through the nostril, passes the nasopharynx and esophagus, and reaches the stomach. Ideally, it should be positioned approximately 10 cm below the gastroesophageal junction, but in clinical practice, bronchial misplacement occurs in 2–4% of NG tube insertions [

1], which may lead to pneumonia or pneumothorax [

2], or even death. Therefore, confirming NG tube placement is crucial in clinical practice. However, most existing deep learning (DL) approaches in this domain have focused solely on binary classification of NG tube position without providing explicit spatial localization or trajectory visualization for the clinician [

3,

4].

Chest X-ray is the standard method for confirming NG tube placement. However, interpreting chest radiographs can be challenging for junior physicians [

3], and difficulties may persist even when standard criteria are applied. Furthermore, radiographic confirmation delays feeding by more than 2 h in approximately 51% of cases [

2]. Thus, there is an unmet clinical need for a system that assists in chest radiograph interpretation and shortens confirmation time, thereby enabling enteral feeding.

Recently, DL methods have shown remarkable performance in medical image analysis, including detection, segmentation, and classification tasks [

5]. These models have also been applied to identify tubes and lines on chest radiographs, yielding promising results [

6,

7]. Our previously developed dual-stage model uniquely integrates a segmentation and a classification module, thereby enabling both accurate placement assessment and interpretable visualization of the NG tube trajectory [

8]. This model achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 99.72% for classification, and not only classifies cases as complete (safe for feeding) or incomplete (unsafe for feeding) but also provides a detailed spatial representation of the NG tube path, assisting physicians in verifying its placement [

8].

Albumin is the major component of colloid oncotic pressure, but hypoalbuminemia reduces this pressure, resulting in pulmonary edema [

9]. Similarly, renal dysfunction or patients with cardiomegaly can contribute to fluid overload and pulmonary congestion. Pulmonary edema increases the radiographic brightness of the lung fields, thereby reducing the contrast between radiopaque medical devices and surrounding tissues. This effect can make it more challenging to detect the tip of NG tubes. A previous study showed that high body mass index (BMI) and male sex were associated with a risk of insufficient visibility of an NG tube on an X-ray. This is because X-ray penetration is reduced in patients with higher BMI, and males typically exhibit higher BMI than females [

10]. Since albumin, renal function, cardiomegaly, BMI, and sex may affect the visibility of this NG tube, these variables were considered in our analysis.

In this study, we applied the previously developed DL model in a real-world clinical setting. In intensive-care and high-volume hospital settings, delays in radiographic confirmation often postpone enteral feeding and reduce workflow efficiency [

1,

2]; therefore, an artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted system validated under real-world conditions is urgently needed. The aims of this study were (a) to validate the model’s performance and its agreement with physicians and (b) to evaluate the model’s performance under conditions that may affect X-ray visibility. Furthermore, by providing visual feedback of the NG tube trajectory, the model enhances interpretability and clinician trust—critical factors for successful AI adoption in clinical radiographic practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

In this retrospective pilot study, a total of 135 consecutive cases of chest radiographs with NG tubes were collected from Kangwon National University Hospital between March and September 2025. The chest radiograph images used in this study were acquired using digital radiography systems from Simens (FLUOROSPOT Compact FD, Munich, Germany) and Samsung (GM85, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The imaging parameters for the FLUOROSPOT Compact FD were 77 kV and 2 mAs, while those for the GM85 were 85 kV and 2 mAs. All radiographs were obtained as portable examinations for patients admitted to the hospital wards.

A radiologist (S.J.E., 8 years of clinical experience) and a pulmonologist (O.B.K., 12 years of clinical experience) independently reviewed all cases and classified them as either complete or incomplete in a blinded manner. Cases were defined as complete if feeding through the NG tube was considered safe, and incomplete otherwise. The time taken by the radiologist and the pulmonologist to confirm the chest radiographs with the aid of the DL model was measured. The DL model generated a probability score between 0 and 1 for each case, with higher values indicating a higher likelihood of correct (complete) NG tube placement. Based on our previous model development study, which demonstrated an AUC of 99.72%, a strict probability threshold of 0.90 was established [

8]. This conservative threshold was selected to maximize specificity and minimize false-positive classifications (i.e., identifying a misplaced tube as safe), thereby prioritizing patient safety in clinical practice. Scores greater than 0.90 were classified as complete, whereas those ≤0.90 were classified as incomplete. Agreement among the radiologist, the pulmonologist, and the DL model was assessed using Cohen’s κ, PABAK, and Gwet’s AC

1 coefficients.

Patients’ demographic data including age, sex, and BMI and laboratory data including white blood cell (WBC), hemoglobin, platelet, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and cardiac–thoracic (CT) ratio were collected. Because devices such as central lines, pacemakers, or artificial valves could affect the analysis, the presence of these devices was additionally recorded. To explore factors associated with model misclassification, cases were divided into two groups: correctly classified and misclassified. Because the number of misclassified cases was extremely small, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables.

In clinical settings, after NG tube insertion, patients are sent to take chest radiographs and nurses contact the physicians to confirm the images. The time intervals between NG tube insertion and chest radiograph acquisition were extracted from the electronic medical records (EMR). Similarly, the time intervals between radiograph acquisition and the physician’s confirmation of the findings were also obtained from the EMR. The time between X-ray acquisition and physician confirmation from the EMR and the time taken by the physicians with the aid of the deep learning model were measured.

2.2. Model Explanation

We utilized the DL-based dual-stage model developed and comprehensively characterized in our previous study [

8]. This comprehensive workflow, which consists of segmentation, concatenation, and classification, is fully illustrated in

Figure 1 of our previous study [

8].

This architecture comprises segmentation and classification stages. Specifically, nnU-Net (version 2.5.1) was employed for the segmentation stage, which precisely delineates the location and trajectory of the NG tube within the chest radiograph. This module achieved robust segmentation performance, achieving a Dice Similarity Coefficient of 65.35% and a Jaccard coefficient of 57.49% on the dedicated testing set. These metrics are significant given the fine, linear structure of the tube.

The classification stage is critically informed by the segmentation output through a concatenation step. The input for the classification model is created by combining the original X-ray image with the segmented line mask, which encodes the tube’s shape and path information, and results in an enhanced, multi-channel input. This novel approach imparts essential shape awareness to the subsequent classification module. The enhanced input is then fed into the classification model, utilizing a ResNet50 architecture pre-trained with MedCLIP [

11] for the final prediction. This model predicts the probability of the NG tube positioning being classified as ‘complete’ or ‘incomplete’ (malposition).

This model was trained on 1799 chest radiographs collected from three major institutions (Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Gangneung Asan Hospital, and Kangwon National University Hospital). All networks and experimental settings were implemented using the PyTorch framework (version 2.4.1.) under Python 3.11.9, with CUDA 12.1 and cuDNN 9 libraries. The prototype is accessible at

https://ngtube.ziovision.ai (accessed on 25 October 2025). The model parameters were fixed, and no additional training or fine-tuning was performed. This study represents an internal retrospective evaluation using a fully pre-trained model. Statistical analysis was performed using R software, version 4.4.2. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

4. Discussion

NG tube insertions are among the most common procedures in critically ill patients [

14], who are typically elderly and have a high prevalence of comorbidities [

15]. A decreased serum albumin level is significantly associated with aging [

16]. Due to these factors, patients requiring an NG tube for feeding are often elderly, have comorbidities such as chronic renal dysfunction and heart failure, and exhibit low serum albumin levels. These conditions can contribute to pulmonary edema, which makes it difficult to distinguish radiopaque devices, such as NG tubes, from surrounding structures. Misplacement or delayed recognition of NG tube position can cause aspiration pneumonia, esophageal perforation, or even fatal complications; therefore, rapid and reliable confirmation is crucial in critical care workflows [

17].

As shown in

Table 1, cases enrolled in this study were older adults, with a median age in the elderly range. Most patients were male, and the median BMI fell within the normal range for the Asian population. Laboratory values, including serum albumin, BUN, creatinine, and eGFR, reflected a population with chronic illness and reduced physiological reserve. When comparing correctly classified and misclassified cases, no statistically significant differences were observed for any clinical or radiographic variables. However, because the number of misclassified cases was extremely small (

n = 6), the analysis was underpowered in detecting meaningful associations. Larger studies including more incomplete cases are required to determine whether specific patient or radiographic characteristics contribute to model failure.

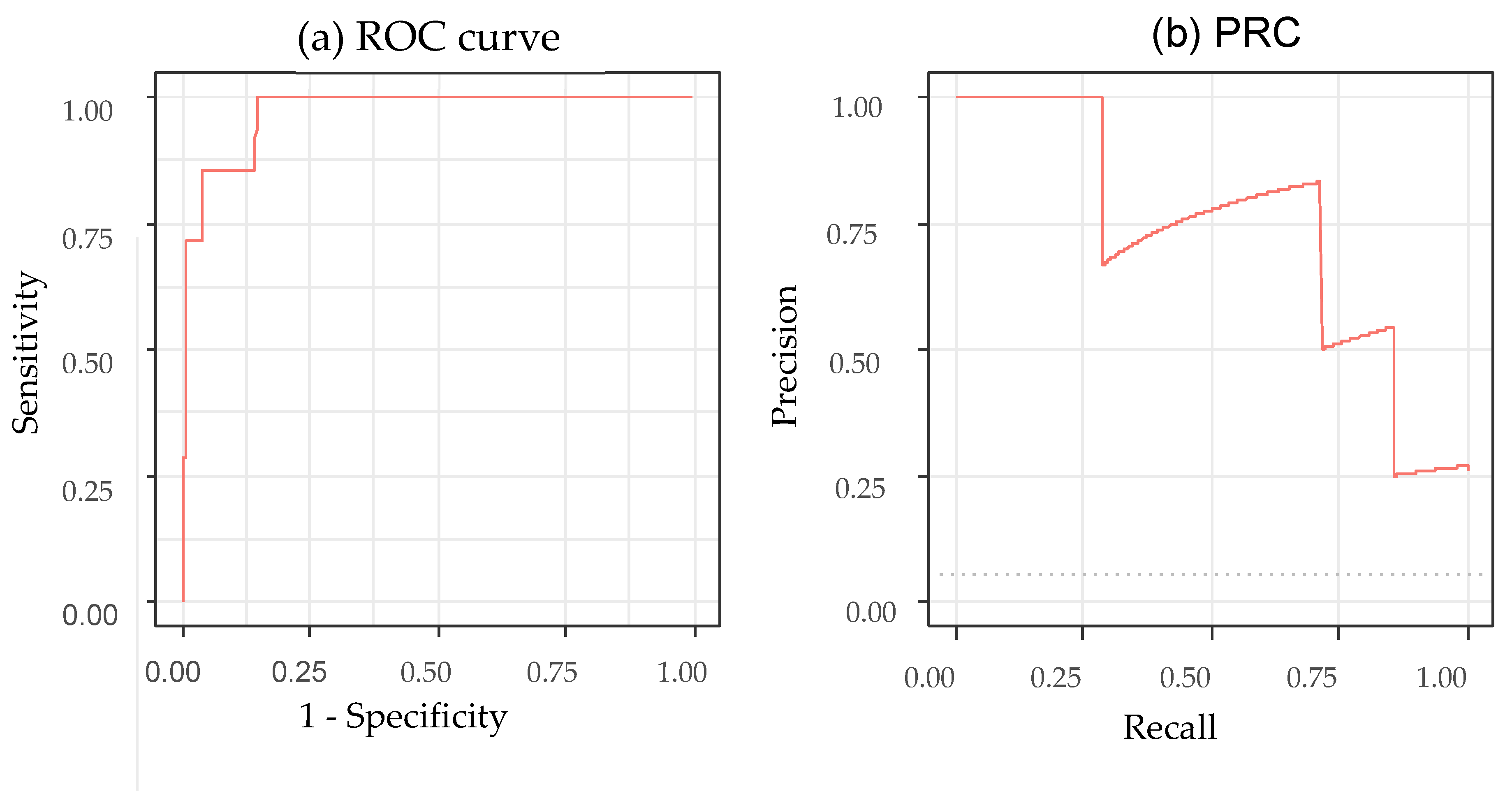

The performance metrics in

Table 3 demonstrate that the model reliably identified correctly positioned NG tubes but was less consistent in detecting incomplete placements. The high sensitivity and PPV were largely due to the predominance of complete cases; therefore, these values likely overestimate the true performance under balanced conditions. By contrast, the NPV and balanced accuracy were lower, indicating reduced stability in the minority class; curve-based metrics further highlighted this limitation. Although the AUC was higher (0.970) than that in a previous study which achieved an AUC of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.88–0.93) [

3], its 95% CI (0.929–1.000) and the area under the RPC for incomplete detection (0.727, 95% CI: 0.289–1.000) reflect substantial uncertainty due to the very small number of incomplete cases. These findings suggest that the model’s performance for identifying malpositioned tubes remains insufficiently reliable, particularly in safety-critical scenarios. Overall, while the model shows promise for assisting in NG tube confirmation, it cannot be used as a standalone decision tool. Larger and more balanced datasets—especially with increased numbers of incomplete or malpositioned tubes—are required to better characterize model failures and to ensure safe clinical integration.

In this pilot evaluation, the DL model showed a high level of agreement with the physicians, achieving a Gwet’s AC1 coefficient of 0.956. However, these metrics must be interpreted with caution. Given the high prevalence of correctly positioned tubes in our dataset (approximately 95%), the reliability estimates may be influenced by the “prevalence paradox”, where agreement metrics can appear inflated. While the model demonstrated high specificity, the performance on the minority class (incomplete cases) highlights the necessity for further validation on balanced datasets.

The average time interval between NG tube insertion and chest radiograph acquisition was 31.5 min. The average time interval between radiograph acquisition and physician confirmation was 75 min, and in 13 cases (9.63%), the confirmation time exceeded 2 h. These time intervals were retrospectively extracted from the EMR. In a real-world clinical setting, nurses typically contact physicians after the radiograph is obtained, and the physicians subsequently confirm whether the NG tube can be used. Because of heavy clinical workloads, confirmation is frequently delayed. Previous studies reported that radiograph verification delayed NG tube use by ≥2 h in 51% of patients [

2] and one study reported a mean confirmation time of 220 min [

18].

When aided by the DL model, the average time required for the radiologist and pulmonologist to confirm NG tube placement was only 1.21 and 1.33 s, respectively. It is important to note that this “reading time” differs from the total “workflow turnaround time”. The DL model provides near-instantaneous interpretation support, which primarily targets the interpretation latency caused by physician unavailability rather than logistical delays. Therefore, these measurements do not imply a reduction in clinical confirmation time and were not considered part of the model’s performance assessment. Previous DL models for NG tube detection have primarily focused on classification [

3,

7,

19]. By contrast, the model used in this study provides a visualization of the NG tube trajectory, facilitating identification of the tube tip. Integrating AI models directly into PACS or clinical decision-support platforms could streamline verification steps and reduce overall feeding delays, similar to prior studies demonstrating workflow acceleration through AI-assisted radiograph triage [

20].

4.1. Failure Case Analysis and Safety Implications

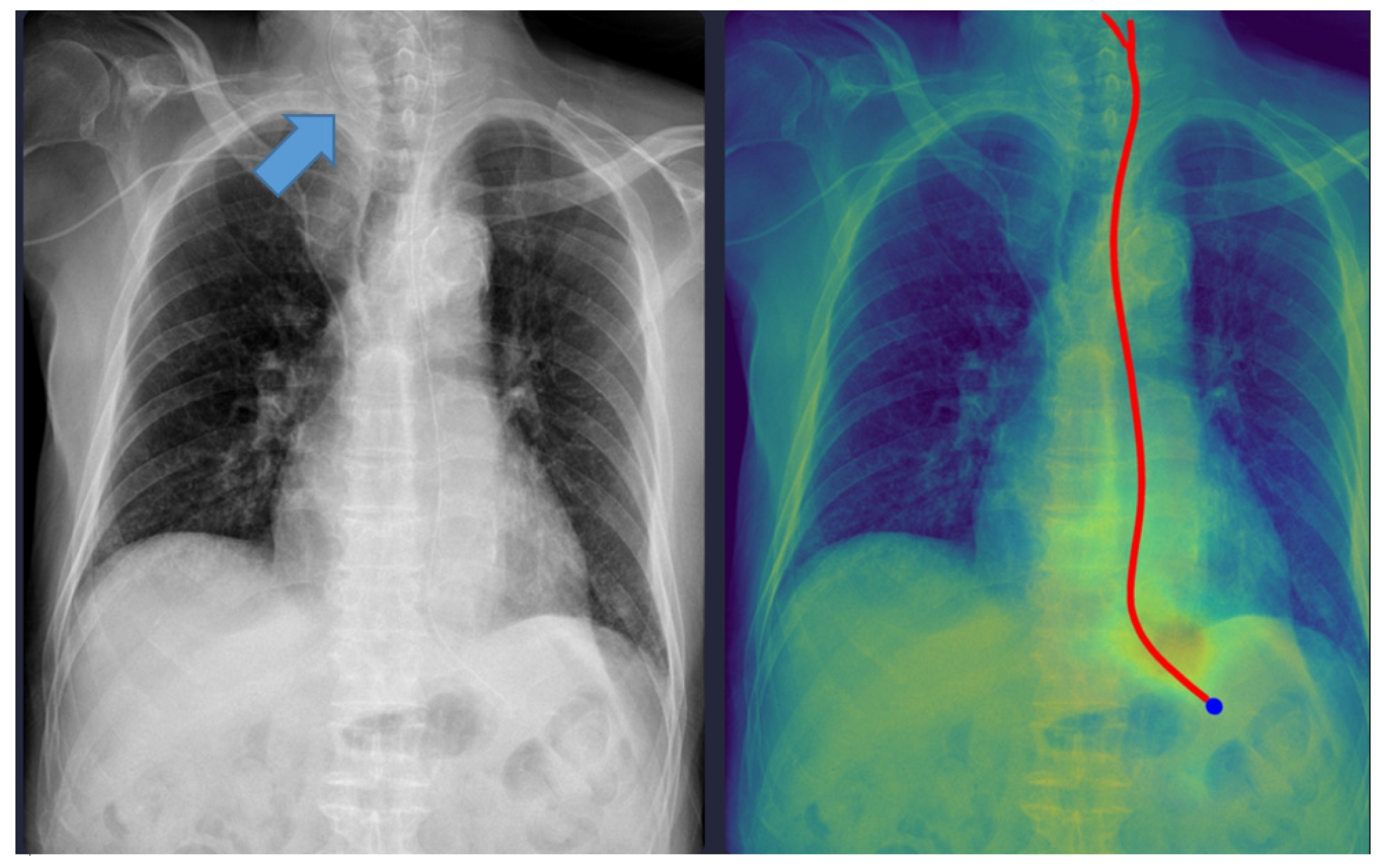

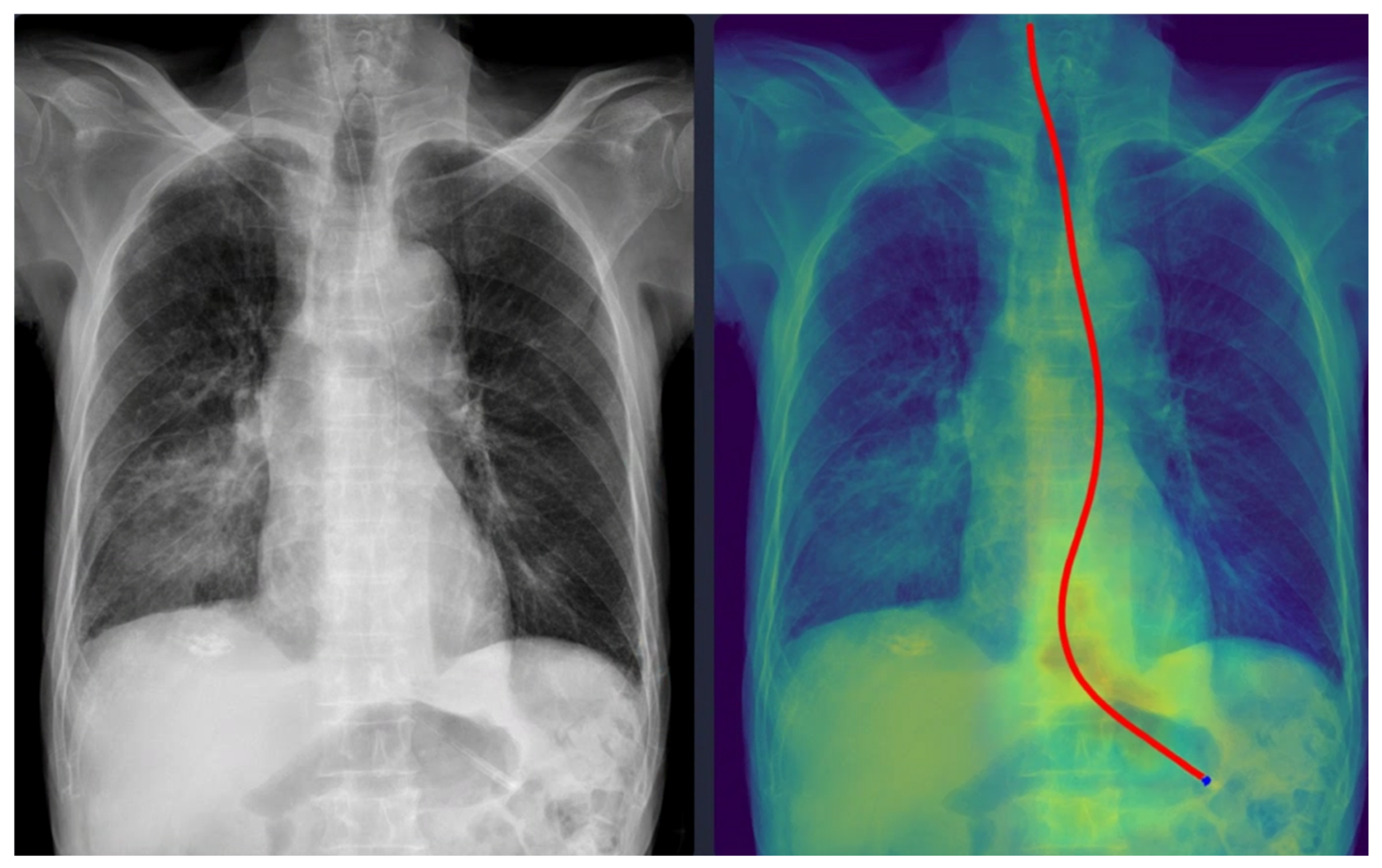

Although the physicians agreed in all cases, six cases were discordant between the physicians and the DL model. One case was misclassified as ‘complete’ despite the NG tube being incompletely inserted (coiled), which could have been potentially fatal. As shown in

Figure 2, the model interpreted it as complete because the tip of the NG tube was projected below the gastroesophageal junction level. The standalone Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM)-based heatmap and standalone segmentation-derived probability map are shown separately in

Supplementary Figure S1. This figure demonstrates the interpretability of our model, which provides images of both maps overlaid together.

Technical and Clinical Analysis: Technically, this error likely stems from the models’ reliance on the vertical coordinate of the tube tip in the 2D projection. While the segmentation module correctly identified the tube structure, the classification head failed to recognize the “coiling” or “looping” morphological feature as a risk factor, likely due to the scarcity of such anomalous patterns in the training dataset. Clinically, initiating feeding through a coiled tube can lead to aspiration pneumonia. This failure mode highlights the inherent limitation of image-level classification models when dealing with complex 3D spatial configurations compressed into 2D images.

Safety Recommendations: To mitigate this risk, we emphasize that the DL model must strictly function as a “second reader” for trajectory visualization rather than a binary decision maker. In clinical practice, physicians must verify the Grad-CAM-based heatmap or segmentation mask overlaid on the original image. If the heatmap shows any deviation from a linear esophageal path (e.g., widening, looping), the placement must be flagged for manual review regardless of the high probability score. This aligns with the current paradigm of human–AI collaboration, where DL tools act as augmentative aids that enhance efficiency while maintaining physician oversight to ensure patient safety [

21].

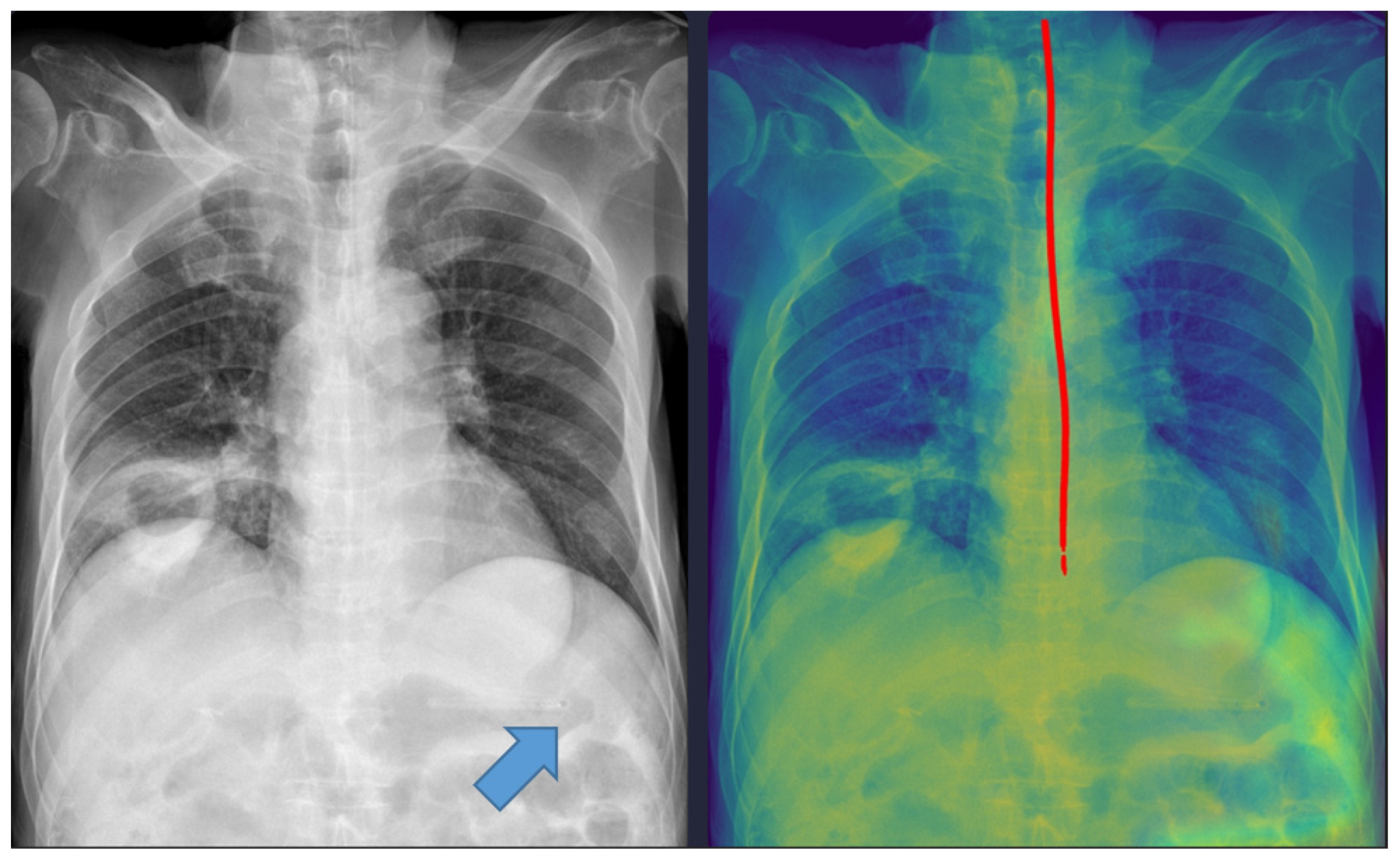

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Five cases were misclassified as incomplete, although the NG tube was correctly positioned in the stomach (

Figure 3). In these cases, the model’s predicted pathway stopped midway, likely because radiopaque structures such as the spine overlapped with the tube. This finding indicates that the model requires additional training with a more diverse dataset to improve its robustness against anatomical noise.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective single-center study with a relatively small sample size. Second, the dataset was collected from the same institution where a portion of the training data originated; therefore, the results represent an internal evaluation rather than full external validation. The generalizability of the model in applying images to the model from different X-ray vendors or different patient populations remains unproven. Third, the cases were highly imbalanced, with most showing correct NG tube placement, which limits the statistical power for evaluating sensitivity to misplacements. Future studies with larger, multi-center datasets that include a higher proportion of incorrect placements and diverse imaging equipment are warranted. Ultimately, explainable DL systems that provide real-time visual feedback may enhance both workflow efficiency and diagnostic confidence, contributing to safer and more timely enteral feeding in critical care practice.

5. Conclusions

In this pilot study, we evaluated a previously developed deep learning model for assessing NG tube placement on chest radiographs using real-world clinical data. The model showed strong performance in identifying correctly positioned tubes; however, its ability to detect incomplete placements was limited, as reflected by the low NPV, modest balanced accuracy, and the wide CI of the curve-based metrics. These findings highlight the instability of model performance in the minority class and underscore the challenges posed by the small number of incomplete cases.

Although the model may help streamline the confirmation process, physician oversight remains essential, particularly in safety-critical scenarios where misclassification could lead to patient harm. Therefore, the current model should be considered an assistive tool rather than a replacement for expert interpretation. Future work should include larger, multi-center datasets with more incomplete cases to better characterize model failure modes and establish more reliable, generalizable performance estimates.