The Incidence and Characteristics of Pelvic-Origin Varicosities in Patients with Complex Varices Evaluated by Ultrasonography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Low-Extremity DUS

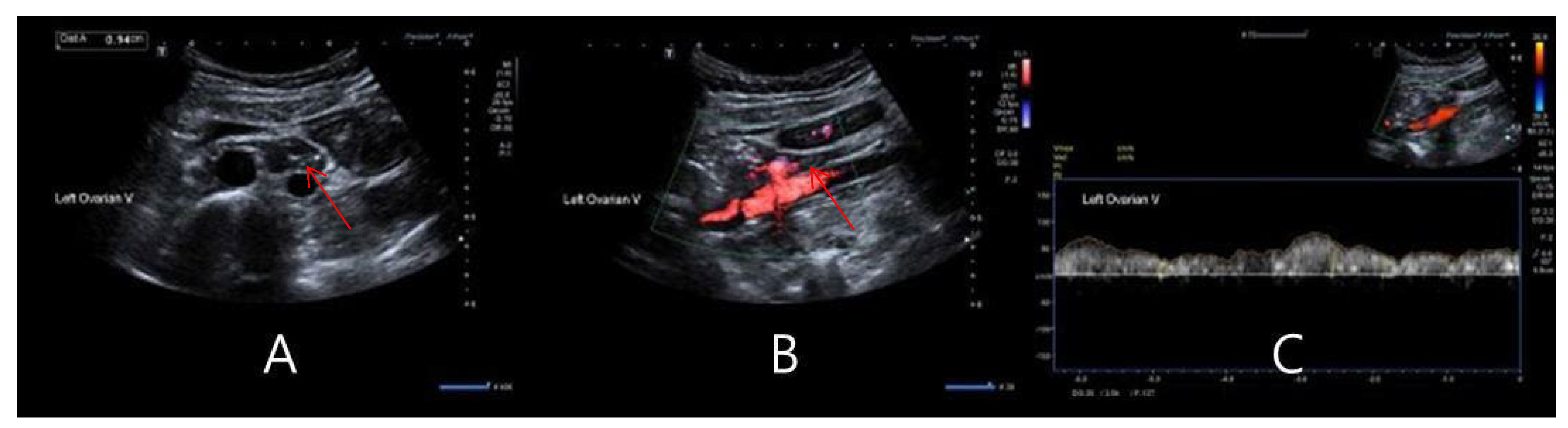

2.3. Gonadal Vein DUS

2.4. Cut-off Values for Significant Reflux

2.5. Computer Tomographic (CT) Imaging of the Gonadal Vein

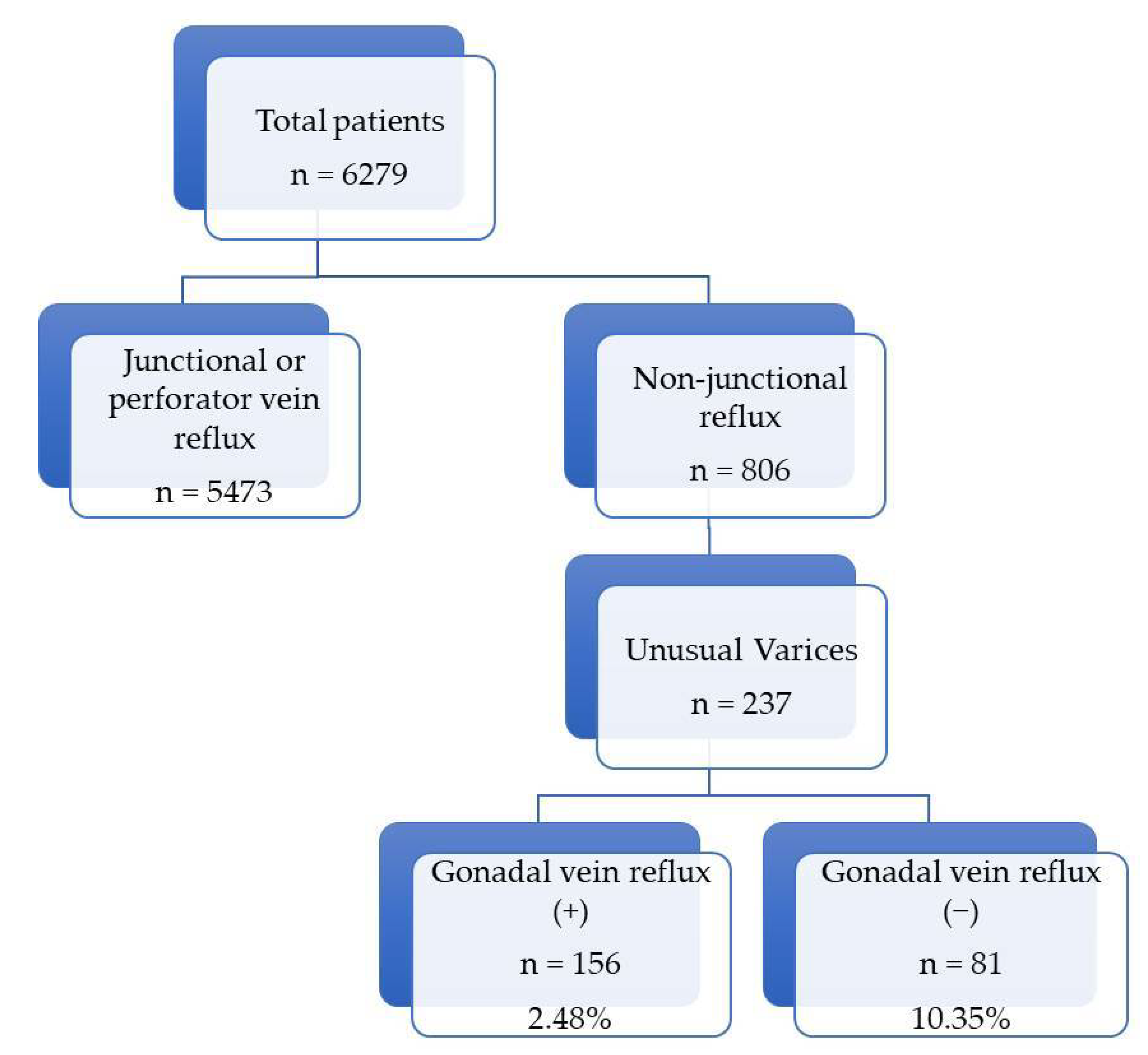

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaplan, R.M.; Criqui, M.H.; Denenberg, J.O.; Bergan, J.; Fronek, A. Quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: San Diego population study. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003, 37, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.J.; Guest, M.G.; Greenhalgh, R.M.; Davies, A.H. Measuring the quality of life in patients with venous ulcers. J. Vasc. Surg. 2000, 31, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Garratt, A.M.; Guest, M.; Greenhalgh, R.M.; Davies, A.H. Evaluating and improving health-related quality of life in patients with varicose veins. J. Vasc. Surg. 1999, 30, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, P.; Patel, S.T.; Heller, J.A.; Deitch, J.S.; Krishnasastry, K.V.; Bush, H.L.; Kent, K.C. Why insurers should reimburse for compression stockings in patients with chronic venous stasis. J. Vasc. Surg. 2002, 35, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balian, E.; Lasry, J.; Coppe, G.; Borie, H.; Leroux, A.; Bryon, D. Pelviperineal venous insufficiency and varicose veins of the lower limbs. Phlebolymphology 2008, 15, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Sutaria, R.; Subramanian, A.; Burns, B.; Hafez, H. Prevalence and management of gonadal venous insufficiency in the presence of leg venous insufficiency. Phlebology 2007, 22, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, J.T. Varicose veins arising from the pelvis due to gonadal vein incompetence. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2005, 59, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.C. Vascular congestion and hyperemia: Their effect on structure and function in the female reproductive system. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1949, 57, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarashvili, Z.; Antignani, P.L.; Monedero, J.L. Pelvic congestion syndrome: Prevalence and quality of life. Phlebolymphology 2016, 23, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- De Maeseneer, M.G.; Kakkos, S.K.; Aherne, T.; Baekgaard, N.; Black, S.; Blomgren, L.; Giannoukas, A.; Gohel, M.; de Graaf, R.; Hamel-Desnos, C.; et al. Editor’s choice–European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic venous disease of the lower limbs. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 63, 184–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Kalantari, K.; Fahrni, G.; Rotzinger, D.C.; Qanadli, S.D. Insights into pelvic venous disorders. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullin, G.M.; Smith, P.C. An evaluation of Doppler ultrasound and photoplethysmography in the investigation of venous insufficiency. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1992, 62, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blebea, J.; Kihara, T.K.; Neumyer, M.M.; Blebea, J.S.; Anderson, K.M.; Atnip, R.G. A national survey of practice patterns in the noninvasive diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. J. Vasc. Surg. 1999, 29, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markel, A.; Meissner, M.H.; Manzo, R.A.; Bergelin, R.O.; Strandness, D.E. A comparison of the cuff deflation method with Valsalva’s maneuver and limb compression in detecting venous valvular reflux. Arch. Surg. 1994, 129, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, A.N. Cardiovascular Disease Educational and Research Trust; European Society of Vascular Surgery; The International Angiology Scientific Activity Congress Organization: Dallas, TX, USA, 1997; pp. 5–9.

- Labropoulos, N.; Mansour, M.A.; Kang, S.S.; Gloviczki, P.; Baker, W.H. New insights into perforator vein incompetence. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 1999, 18, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abai, B.; Labropoulos, N. Duplex ultrasound scanning for chronic venous obstruction and valvular incompetence. In Handbook of Venous Disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- O’donnell, T.F.; Passman, M.A.; Marston, W.A.; Ennis, W.J.; Dalsing, M.; Kistner, R.L.; Lurie, F.; Henke, P.K.; Gloviczki, M.L.; Eklöf, B.G.; et al. Management of venous leg ulcers: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery® and the American Venous Forum. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 3S–59S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, R.T.; Raffetto, J.D. Chronic Venous Insufficiency. Circulation 2014, 130, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funatsu, A.; Anzai, H.; Komiyama, K.; Oi, K.; Araki, H.; Tanabe, Y.; Nakao, M.; Utsunomiya, M.; Mizuno, A.; Higashitani, M.; et al. Stent implantation for May–Thurner syndrome with acute deep venous thrombosis: Acute and long-term results from the ATOMIC (AcTive stenting for May–Thurner Iliac Compression syndrome) registry. Cardiovasc. Interv. Ther. 2019, 34, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwanabol, P.A.; Tefera, G.; Schwarze, M.L. Syndromes associated with the deep veins: Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, May-Thurner syndrome, and nutcracker syndrome. Perspect. Vasc. Surg. Endovasc. Ther. 2010, 22, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.T.; Gillespie, D.L. Diagnosis and treatment of the pelvic congestion syndrome. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2015, 3, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, P.; Mendoza, E.; Gianesini, S. General Considerations to the Treatment of Pelvic Leak Points, Ch. 8. In Saphenous Vein-Sparing Strategies in Chronic Venous Disease; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Francheschi, C.; Bahnini, A. Treatment of lower extremity venous insufficiency due to pelvic leak points in women. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2005, 19, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C. Anatomie fonctionnelle et diagnostic des points de fuite bulboclitoridiens chez la femme (point C). J. Mal. Vasc. 2008, 33, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianesini, S.; Antignani, P.L.; Tessari, L. Pelvic congestion syndrome: Does one name fit all? Phlebolymphology 2016, 23, 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, A.M.; Taylor, D.C.; Dos Santos, S.J.; Whiteley, M.S. Pelvic venous reflux is a major contributory cause of recurrent varicose veins in more than a quarter of women. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2014, 2, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, S.; Oswald, M.A. Proposal for a protocol for sex hormones level sampling in patients with varices to evidence pelvic reflux. JTAVR 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gonadal Vein Reflux (+) (n = 156) | Gonadal Vein Reflux (−) (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex differences (M/F) | 1/155 | 1/80 |

| Age | 53.69 ± 12.53 | 53.03 ± 13.05 |

| Height | 158.02 ± 7.61 | 158.02 ± 6.70 |

| Weight | 58.52 ± 8.21 | 60.90 ± 8.48 |

| BMI | 23.56 ± 3.72 | 24.43 ± 3.45 |

| Risk Factor | ||

| No | 129 (82.6%) | 58 (71.6%) |

| Pregnancy | 8 (5.1%) | 6 (7.4%) |

| Deep vein thrombosis history | 0 (0%) | 3 (3.7%) |

| Previous varicose vein operation | 15 (9.6%) | 6 (7.4%) |

| Treatment | ||

| Medication only | 27 (17.3%) | 18 (22.2%) |

| Compression stocking only | 51 (32.7%) | 24 (29.6%) |

| Medication + compression stocking | 35 (22.4%) | 11 (13.6%) |

| Operation | 19 (12.2%) | 12 (14.8%) |

| Gonadal Vein Reflux (+) (n = 156) | Gonadal Vein Reflux (−) (n = 81) | |

|---|---|---|

| Telangiectasis or reticular veins | 17 (10.9%) | 10 (12.3%) |

| Varicose vein with leg pain | 80 (51.3%) | 40 (49.4%) |

| with pelvic pain | 38 (24.4%) | 19 (23.5%) |

| without symptoms | 5 (3.2%) | 2 (2.5%) |

| Edema | 16 (10.3%) | 9 (11.1%) |

| Changes in skin and subcutaneous tissue | 0 | 1 (1.2%) |

| Left Gonadal Vein Reflux (n = 18) | Bilateral Gonadal Vein Reflux (n = 1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bilateral legs | 4 | 0 |

| Right leg | 13 | 1 |

| Left leg | 1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoo, K.C.; Park, H.S.; Shin, C.S.; Lee, T. The Incidence and Characteristics of Pelvic-Origin Varicosities in Patients with Complex Varices Evaluated by Ultrasonography. Tomography 2024, 10, 1159-1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography10070088

Yoo KC, Park HS, Shin CS, Lee T. The Incidence and Characteristics of Pelvic-Origin Varicosities in Patients with Complex Varices Evaluated by Ultrasonography. Tomography. 2024; 10(7):1159-1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography10070088

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoo, Kwon Cheol, Hyung Sub Park, Chang Sik Shin, and Taeseung Lee. 2024. "The Incidence and Characteristics of Pelvic-Origin Varicosities in Patients with Complex Varices Evaluated by Ultrasonography" Tomography 10, no. 7: 1159-1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography10070088

APA StyleYoo, K. C., Park, H. S., Shin, C. S., & Lee, T. (2024). The Incidence and Characteristics of Pelvic-Origin Varicosities in Patients with Complex Varices Evaluated by Ultrasonography. Tomography, 10(7), 1159-1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography10070088