2.2. Overall Configuration Optimization of Variable Camber Wings

The flaps installed at the trailing edge of the wing typically constitute 25–35% of the overall wing profile chord length. Using the wing of a typical medium-sized transport aircraft as the reference design size, the total chord length of the wing has been established to be 3.33 m, with a trailing edge variable camber section measuring 1 m, accounting for 30% of the chord length of the trailing edge flap. Additionally, based on the existing flap system, the target deflection angle for the trailing edge of the chord variable camber section has been determined to be 30°. The NACA0012 airfoil was used as the basic airfoil for both the design and its optimization.

Structural design usually consists of three parts: input point, structure, and output point. The output point set of the chordwise variable camber trailing edge is the outer rib structure contour. Furthermore, the input point is the driving position, which can be divided into centralized single-point drive and distributed drive. The centralized single-point driving method has defects such as relatively single-load transfer path, easy to produce local stress concentration, uneven deformation, and poor smoothness. Further analysis of the continuous variable bending demand in the mean camber line of the airfoil trailing edge has shown that the wing trailing edge deformation is similar to that of the cantilever beam under load. Moreover, the initial and tip arc deformation segments in the cantilever beam trailing edge show similar slope distribution [

23].

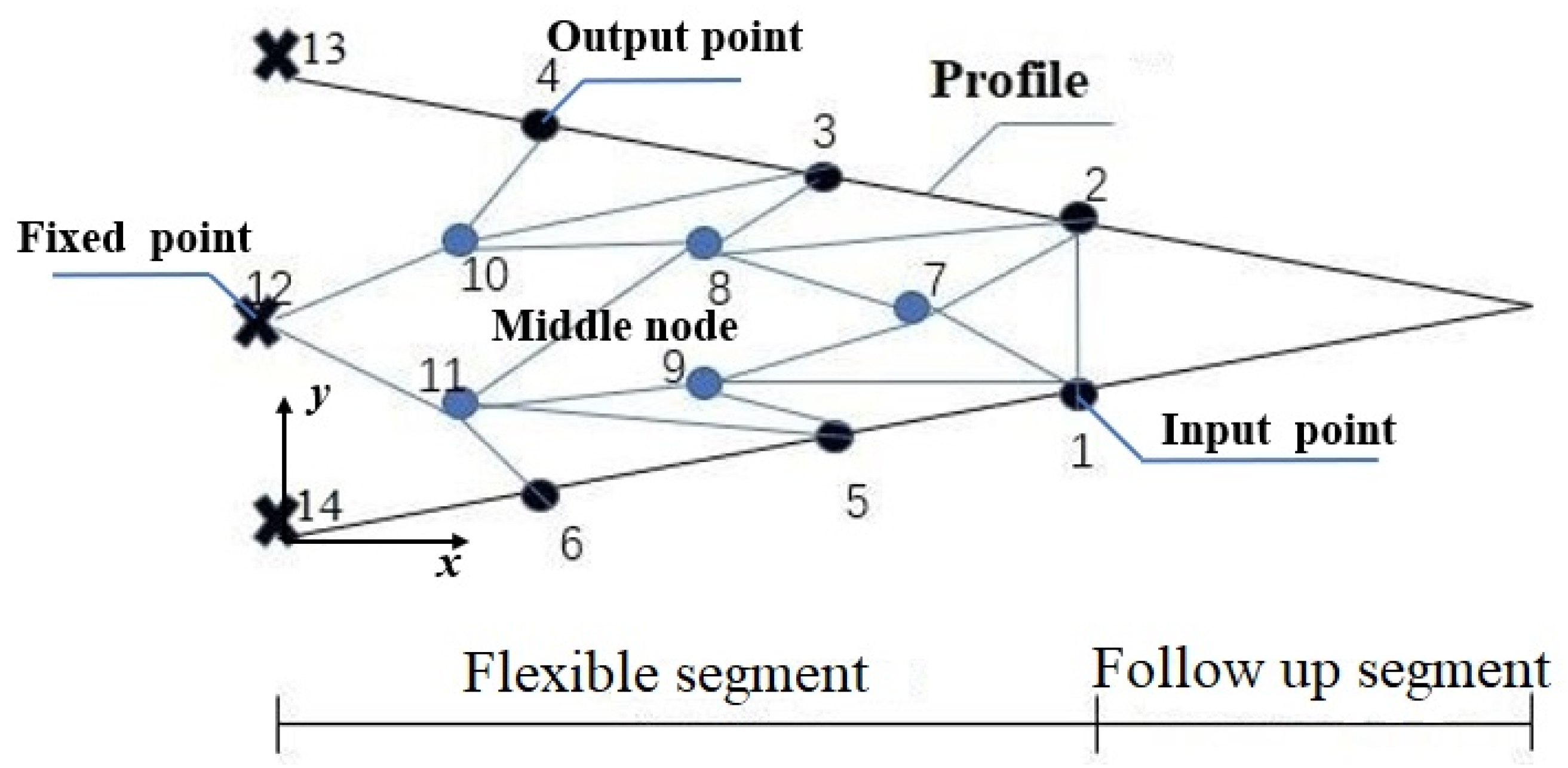

Considering the elastic-allowable deformation of the wing rib material and distributed drive form, a hybrid structure coupling deformable wing rib design was proposed, as shown in

Figure 1. In the variable bending section of the wing trailing edge, structure types were arranged alternately in three sections. They were rigid segment, flexible segment, and follow-up segment, which accounted for 30%, 40%, and 30% of the total wing trailing edge.

The optimization of the bending configuration is not the focus of this article, but to ensure the readability and coherence of the text, we will briefly introduce the process of configuration optimization here.

To describe the diversity and continuity of the downward bending of the trailing edge flaps of an aircraft wing, the variable camber configuration can be equivalently described using the mean camber line. Thus, a relatively intricate issue concerning the parameterization description of airfoils can be converted into a problem of curve parameterization description. We utilize cubic spline equations to delineate the mean camber line of the airfoil.

In

Figure 2, the six points (m0 to m5) are located on the mean camber line of the airfoil, where m0 is the leading edge point of the variable wing camber section and m5 is the trailing edge point. Furthermore, m1 and m4 are the rigid–flexible junction points, while m2 and m3 are points with x-coordinates of 40% and 60% of the trailing edge chord length, respectively. Moreover, points m2 and m3 are located on the middle flexible segment arc [

21].

The geometric relationship was obtained by introducing the coordinates of each point into Formula (1). The y-coordinate of each point was selected as the optimization variable.

where

are the initial mean camber line deflection point coordinates,

are the trailing edge coordinates of the mean camber line,

represents the variable curvature section arc length, and

is the equivalent deflection angle of the variable curvature section.

The maximum lift-to-drag ratio coefficient was selected as the evaluation function for finding the optimal variable bending configuration [

21], as follows:

In

Figure 2, point m1 serves as the connection between the rigid rotation segment and the flexible segment. Given the relatively independent driving methods of these two segments, the tangent slope at this point will vary, and a certain degree of deviation should be allowed. However, considering the continuity of the overall airfoil camber change, it is stipulated that the sudden change in the deflection angle caused by this deviation should be less than 10% of the overall deflection angle. The deformation target angle is set at a 30° downward deflection of the trailing edge of the wing, which is the maximum design deflection angle corresponding to the takeoff/landing state of the aircraft. The lift-to-drag ratio is calculated using the XFoil two-dimensional airfoil aerodynamic calculation software. Additionally, the flow field parameters are set to the takeoff/landing conditions, as shown in

Table 1.

The coordinates in the optimization variables are updated using genetic algorithms. The optimization process was established using the following constraints: the material strength limitation, maximum allowable equivalent chord deflection angle of 15° for the flexible segment, and the follow up segment. The optimal coordinates obtained from each generation of optimization are normalized. Then, the airfoils are generated and the lift-to-drag ratio is computed. Finally, the generated optimal chordwise variable camber airfoil is compared with an airfoil having a mean camber line in the form of a cantilever beam.

2.3. Structural Optimization of the Flexible Segment

The structural optimization of the wing rib trailing edge structure design is necessary to ensure the smooth wing rib structure and continuous deformation. The rigid deflection segment is driven by servo motor and linkage mechanism. Making the design of the flexible segment configuration and driving mode is challenging. When the structural form is unknown, the topology optimization method can generally be used to design the structural configuration.

The ground structure method is often used for the topology optimization of discrete structures. However, due to its dependence on initial nodes and the corresponding full-base structure, there may be a risk of local optimal solutions and free elements that are disconnected from the structure. The load path method is similar to the ground structure method in the initial layout; however, its optimization approach is different. The characteristic design domain points are connected by the load path transfer form. As the load path method directly tracks the force transmission path within the structure, making it clear how loads are transferred from input points to output points, it provides an intuitive representation of the structural loading logic. In contrast to the ground structure method, this method can drastically reduce the number of redundant elements and improve optimization efficiency. The diversity of the topology solutions is controlled by both the position and number of intermediate points. Firstly, the appropriate number of nodes is arranged in the design domain, and the initial design-domain topological structure is given through the full base configuration. Then, the load path is parameterized and discretized to create path forms, different from the load input point, to the output point. Subsequently, appropriate design variables, such as path number and path weight, are used to find the optimal path from the load input to the output point. The optimization algorithm and finite element method are used for calculation. Finally, all the structures covering these paths are combined, obtaining the final topology.

Taking the flexible segment of the trailing edge variable camber rib structure as an example, the topology optimization design domain is shown in

Figure 3.

According to the flexible segment deformation requirements, output points are evenly distributed on the upper and lower wing rib surfaces, with a total of six output points (points 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). There is one input point, and, since its position is at the lower wing rib edge, it is both the input and output point (point 2). The middle node is an important segment of the load path method. Different topological shapes are obtained by varying the number and location of the middle node. Simultaneously, the middle node is also a bridge connecting the elements. Therefore, determining the number of middle nodes and their locations is a rather important task. Considering the completeness of the topological shape results, the optimization calculation efficiency, and the processing feasibility, it is reasonable to select 4–10 intermediate nodes. In this article, five intermediate nodes were used (points 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Points 12, 13, and 14 are fixed, with point 14 having freedom of movement along the X direction.

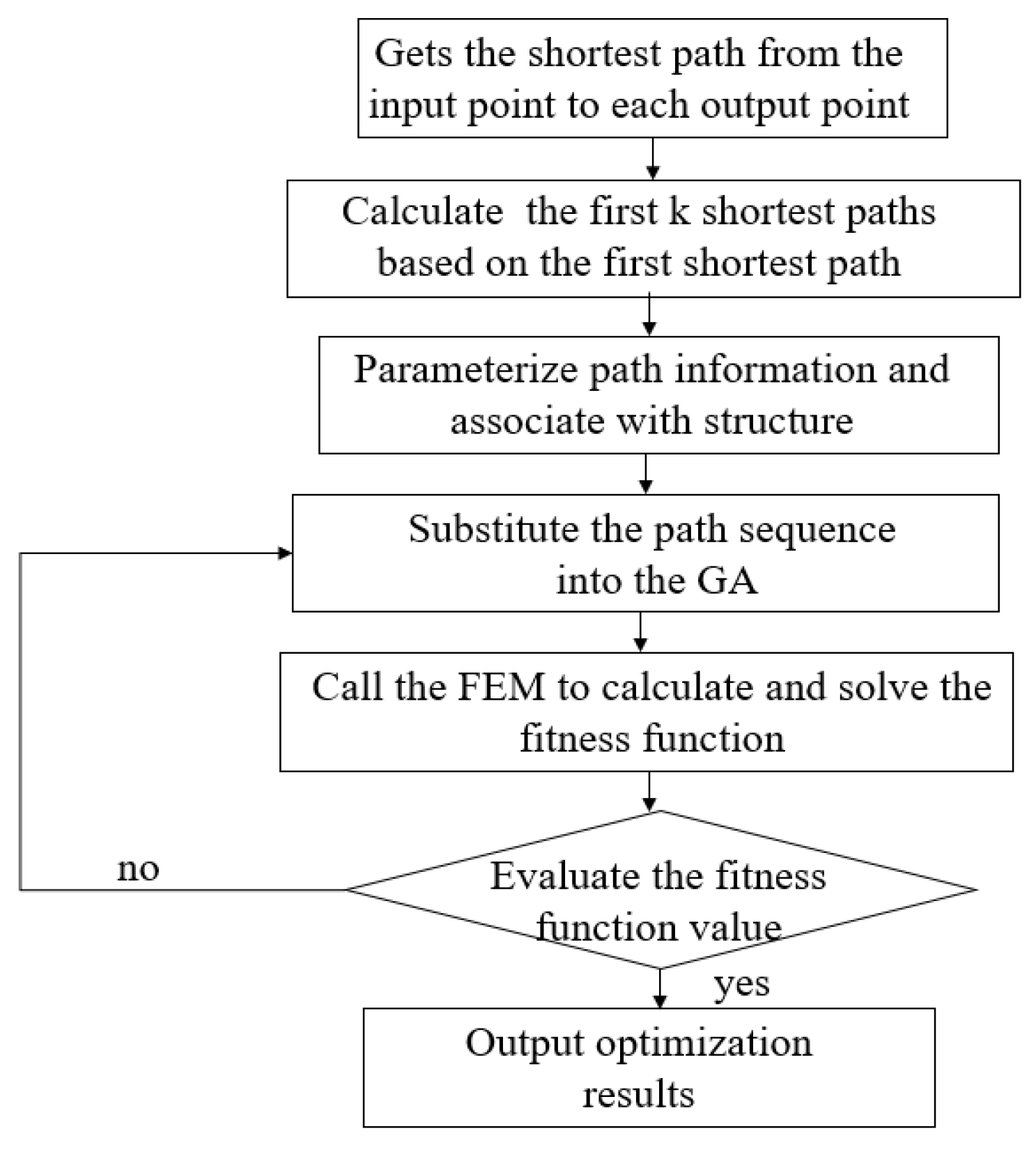

After determining the initial design area topology, each load path must be both determined and parameterized. According to the load path method’s definition, the load path is the path used to transfer the load between the input and output point. Once the topological shape is determined, each element point is calculated accordingly, and the load path associated with it can be determined. The load path method’s algorithm flowchart is given in

Figure 4.

The load path method’s design variables include the load path sequence, the maximum length of the load path, the material Young’s modulus, the input load size and direction, the number and location of element points, and the element section size. In this paper, the structure is a single-input multi-output system. Considering the modeling and optimization complexity, the length weight of the design variable load path was set to one. Furthermore, the structure’s section width was taken as constant and the 7075Al-T6 alloy was selected as the material. Therefore, in the design of the variable trailing edge of the flexible wing based on the load path topology optimization method, the design variables were as follows: load path sequence and the position of the intermediate node.

In

Figure 3, point 1 is the driving load input point, while points 1–6 are the output points located on the upper and lower surfaces of airfoil. Points 12, 13, and 14 are the connection points of the rigid segment and the flexible segment. In order to reduce the stress of flange during deformation, the free degree of point 14 in X direction is released in the finite element model. Firstly, topology optimization based on the load path method requires the identification of the force transfer path from the input point to the output point. Therefore, Dijkstra’s Greedy algorithm is employed to determine the shortest path from the input point to each output point, in order to initially screen effective load paths [

24]. Next, the first

K load transfer paths from the input point to each output point were solved via the shortest path.

In this algorithm, the path matrix had to be solved first. The requirement is that, if the input point is directly connected with the output point, the element is equal to the path weight. The weight of each path in this paper is one. If the input point and the output point are connected through the intermediate point, the element value is infinite. Therefore, the path matrix of the load path method can be given as follows:

Using the first shortest path from the input point to each of the output points, the first

K path sequences from the input point to output points can be obtained via extended calculation. Through analysis, when

K = 4, all paths have covered all the initial base structures. Hence, when

K = 4, each path is used to the subsequent calculation. The structure numbers in the first four paths from the input point to the output point are shown in

Table 2.

Based on the above-provided path numbers, it can be determined whether each beam structure in the design domain is called by the path. If it is, it remains in the finite element model; if not, the beam is deleted. The minimum square difference between the actual variable bending configuration and the target configuration was selected as the space optimization process objective function:

Combined with the finite element model calculation, design variables were iteratively updated according to the objective function. Finally, the topology optimization results of the flexible wing trailing edge were obtained. The internal structure of the flexible structure is shown in

Figure 5, in which the beams represented by thin lines are the beams abandoned in the optimization process.

Aiming to ensure that the actual deformed outer contour will further approach the target contour curve, it is necessary to further optimize the results of topological optimization. In shape optimization and dimensional optimization, the node positions and shape of beam elements and the cross-sectional dimensions of the elements are the optimization variables.

Therefore, the design idea of equal strength variable cross-section curved beam was introduced. The ancient longbow bionic structure and ‘S’ substructure were used to replace the straight beam structure used in the initial topology model.

Table 3 indicates that when using a force form similar to a wing rib as the input load, the longbow structure displays enhanced stability and greater susceptibility to deformation. Meanwhile, in order to improve the structural deformation capability,

Figure 6 presents a comparison between the load displacement curves of a straight beam and an ‘S’-shaped substructure. It was found that the ‘S’ substructure displayed a greater deformation displacement given the same radial load, making it easier for the structure to approach the target contour curve. Therefore, the multiple short beams connecting the input point and the fixed point can be replaced with the longbow-type constant strength variable section curved beam. Consider beams 1-7, 7-8, 8-10, and 10-12 in

Figure 4 as a whole arched beam. The short beam substructure in the upper and lower flanges can be replaced with the ‘S’-type substructure. Replace beams 10-4, 8-3, 11-6, and 11-5 retained through topology optimization in

Figure 4 with ‘S’ type beams, respectively. At the same time, replace beams 8-11, beams 11-9, and beams 9-1 that connect the intermediate points with curved beams.

The structural size and the node location significantly affect the stress level and variable bending configuration during the structural deformation. Therefore, the coupling of the two was introduced during the optimization. For such problems, separate subspaces for various optimization variables are created using their respective evaluation functions, followed by alternating optimization iterations. This is illustrated in

Figure 7.

In the node location optimization subspace, the geometric position of each node was used as the optimization variable. The degree of fit between the actual variable camber configuration and its optimal value of the flexible wing rib structure was used as the evaluation criterion (under the given driving force), as shown in Formula (4).

In the subspace dedicated to size optimization, structural deformation is primarily facilitated by the main beam connecting the input point to the fixed point, whereas the short beam structures linking the main beam to each output point serve to adjust the deformation of the overall structure. Consequently, the stress distribution within each beam structure during the deformation process holds significant importance. Hence, leveraging the equal strength beam theory, size optimization has been conducted on the variable cross-section main beam that spans the entire flexible wing rib structure. In engineering applications, the complexity of structures makes it impractical to maintain consistent stress values across every beam element section. Consequently, during the size optimization of the wing rib’s primary load-bearing beam structure, this paper focuses on selecting key nodes and obtaining their stress values. By updating the optimization variables, we aim to minimize the deviation between the stress values of each section and the target stress values set according to the equal strength beam theory. This is shown in Formula (5).

The rectangular beam cross-section was selected in the structure. When the bending of the wing rib flexible segment structure changes in the chord direction, the beam element thickness H will significantly affect the structural stress level. The main penetrating beam can be divided into the front section, middle section, and tail sections with two key nodes as dividing points. Each beam element was continuously arranged with respect to the sectional points W1–W11. The schematic diagram of sectional point arrangement is shown in

Figure 8.

The genetic algorithm was used for optimization in different subspaces. In each iteration, the finite element analysis of the flexible variable bending process of the structure was carried out. Next, the established evaluation function could be used to determine whether the structural design meets the requirements.

After numerous rounds of optimization and iteration, the expressions for the specific dimensions of the thickness H in the front, middle, and rear sections of the main beam were obtained. Upon normalization, the results are presented as shown in Equation (6):

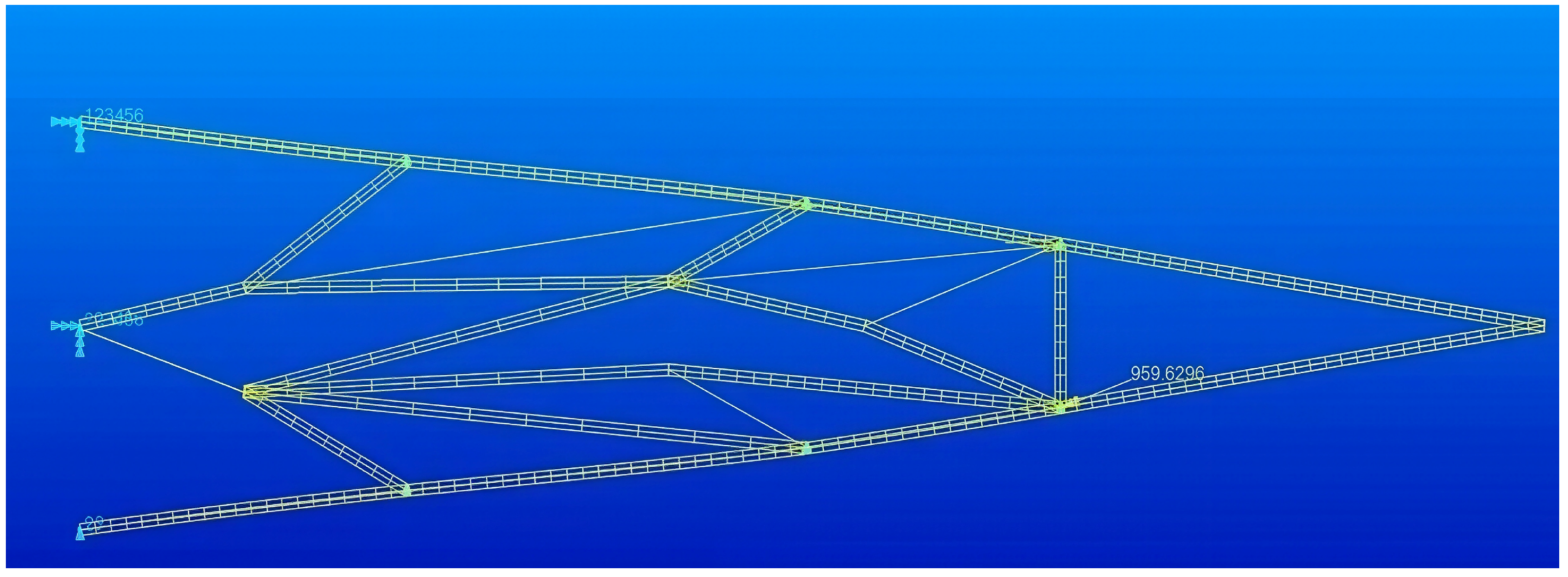

Finite element modeling was performed on the optimized wing rib structure, utilizing 7075Al-T6 as the material. This material boasts an elastic modulus of 72 GPa, a Poisson’s ratio of 0.33, and a density of 2810 kg/m

3. In the modeling process, beam elements were applied to the flexible and follow-up segments, whereas shell elements were used for the rigid rotational segment. Given that this paper primarily investigates the deformation of the flexible segment, the boundary conditions were configured accordingly: the rigid rotational segment was partially fixed, and two out of the three connection points between the flexible and rigid segments were fixed. The connection point at the lower edge of the wing rib was allowed freedom in the X direction to alleviate internal structural stress. When the connection point at the lower edge was also immobilized, indicating that the flexible structure was rigidly connected to the rigid segment at three points, under such boundary conditions, a significantly larger driving force was required to attain the target deformation at the endpoints of the structure. Concurrently, the maximum stress near the connection at the lower edge of the rib and within the ‘S’-shaped substructure located at the lower portion of the rib substantially surpasses the material’s permissible stress, leading to structural damage. The finite element model underwent a stepwise mesh refinement from coarse to fine, with computations carried out on three distinct mesh densities. The results showed that the maximum stress and deformation were both below 2%, confirming mesh convergence, as detailed in

Table 4. Consequently, the second mesh density was ultimately chosen for the calculations, as depicted in

Figure 9.

2.4. Control System Design

The hybrid structure variable camber wing rib in this paper needs distributed driving. The rigid segment uses a servo motor to drive a linkage mechanism for precise deflection control. The flexible structure, the design’s focus, with a longbow-like variable cross-section beam as its main deformation part, uses pneumatic muscle (

Figure 10), an actuator with simple structure, featuring light weight, easy bending and miniaturization. The pneumatic muscle features metallic fixed ends and an air inlet device, while its central portion consists of a rubber cylinder wrapped with metal fibers. Its principle facilitates bow-drawing driving, and is suitable for the wing’s complex narrow space.

Figure 11 depicts the control process for driving and controlling the flexible structural using pneumatic muscles [

21].

Due to the abovementioned control process and controller design, the mathematical modeling of the pneumatic muscle driving force and the wing rib’s flexible segment structure was needed.

Establishing a mathematical model for the driving force of pneumatic muscle is the primary method used to quantify its driving capability, and it also serves as the foundation for constructing a simulation model of the variable bending drive control system for the flexible wing rib structures [

25]. Pneumatic muscle was used as the research object, as shown in

Figure 12.

Here, m is pneumatic muscle quality, L represents the real-time length of the pneumatic muscle, F1 is the elasticity of pneumatic muscle rubber sleeve, F2 is the force load, and F is the pneumatic muscle contraction.

Based on the derivation of the dynamic equations during the pneumatic muscle actuation process in reference [

21], we obtain the expression for the driving force, as follows:

where

is the internal pneumatic muscle pressure,

is the standard atmospheric pressure,

is the length of the single fiber, and

is the number of wraps around the fiber.

The first step in establishing the simulation model of the wing rib’s flexible segment is to identify the structural parameters, as shown in

Table 5.

After analyzing the deformation characteristics of the flexible rib structure, its dynamic model was established using the Lagrangian method, as follows [

21,

26]:

where M is the structure moment of inertia,

C is the structural bending damping,

G is the rotational torque generated by structural gravity,

K is the rotational stiffness of the structural equivalent joint, and, finally,

and

are the control torque and external disturbance, respectively.

In practical applications, physical parameters and disturbances are often inaccurate, and flexible wing rib parameters vary with camber changes. Therefore, system modeling errors must be considered. To obtain an accurate dynamic model, the coefficient terms in the dynamic Equation (8) are divided into deterministic and error components (referred to as the nominal model). Using the sliding mode variable structure control method, the controller expression is obtained as follows [

21]:

where

KP is the proportional coefficient,

Ki is the integral coefficient, and

,

r is the sliding surface function.

is the control rate based on the nominal model and

is the robustness term required to mitigate the system modeling error and external interference; the expression is as follows:

where

, and

are deterministic components of the coefficient of the nominal model and

q is the actual angle signal. The expression for

is as follows:

In Equation (11):

where

,

,

, and

characterize the error components of coefficients of the nominal model.

A simulation platform for a variable bending controller of flexible structures was constructed using Simulink. Taking the bending of a flexible structure by 5° as an example, multiple sets of control parameters (

KP is the proportional coefficient,

Ki is the integral coefficient, and Λ is the sliding mode surface coefficient) were compared. It was determined that when

, the system had the shortest adjustment time, as well as the smallest steady-state error and overshoot (See

Table 6 and

Figure 13) [

21].

The sliding mode variable structure control algorithm has the advantages of quick response and strong robustness. However, it is difficult for the same set of parameters to achieve the best control effect at all possible target angles. Meanwhile, when it is difficult to obtain the optimal parameters, the control effect will also be reduced. To tackle the aforementioned issues, we can draw upon relevant experience obtained from early experimental results and incorporate fuzzy control to fine-tune the parameter settings within the sliding mode control algorithm [

27]. Finally, all the target angles within the scope could be ensured to have good controlling effect. The simulation process is shown in

Figure 14.

Adopting a two-dimensional fuzzy controller, proportional coefficient and integral coefficient are directly adjusted through the fuzzy control rate. Error and its rate of change were set as the input variables for the fuzzy controller.

Firstly, the definition of fuzzy sets is as follows: PB means positive big; PS means positive small, ZO means zero, NS means negative small, and NB means negative big.

Secondly, according to the fuzzy control principle,

and

are defined as the fuzzy control input, and

and

as the fuzzy control output. They can be expressed as in Equation (15).

Thirdly, confirmation of fuzzy control rule and reasoning algorithm: The used fuzzy rule works as follows: If

is A and

is B, then

is C and

is D. The Mamdani reasoning method is employed for reasoning algorithm, which is widely used in fuzzy control. The rules of fuzzy control are shown in

Table 7.

Fourthly, according to the fuzzy control principle, the domain of input parameters

and

, and the output parameters

and

are defined as in Equation (16). The membership function of all the parameters in the fuzzy control is confirmed to be a triangular function.