Nanomechanical and Optical Properties of Anti-Counterfeiting Nanostructures Obtained by Hydrogel Photoresist in Laser Processing

Abstract

1. Introduction

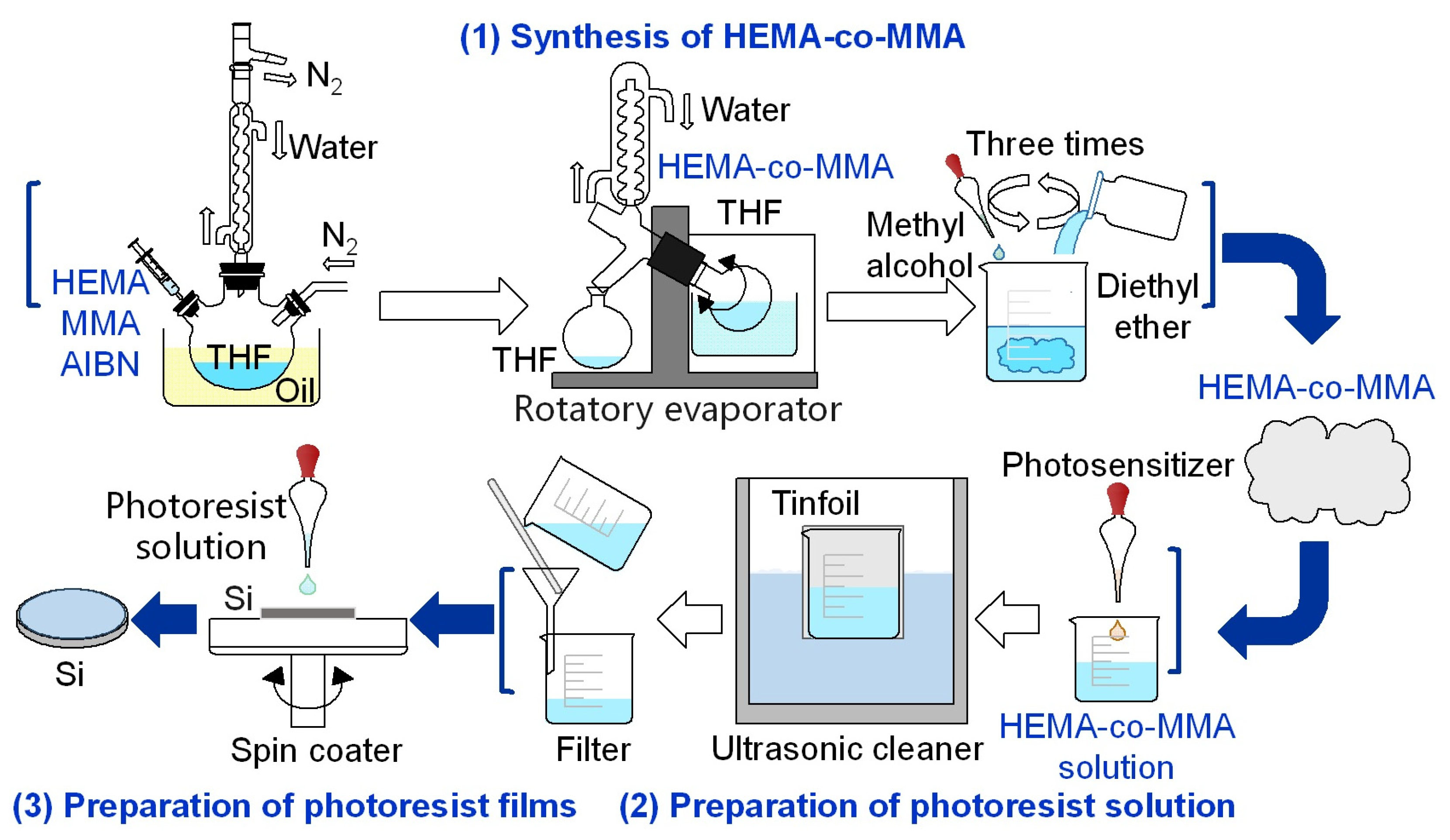

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Optical Simulation

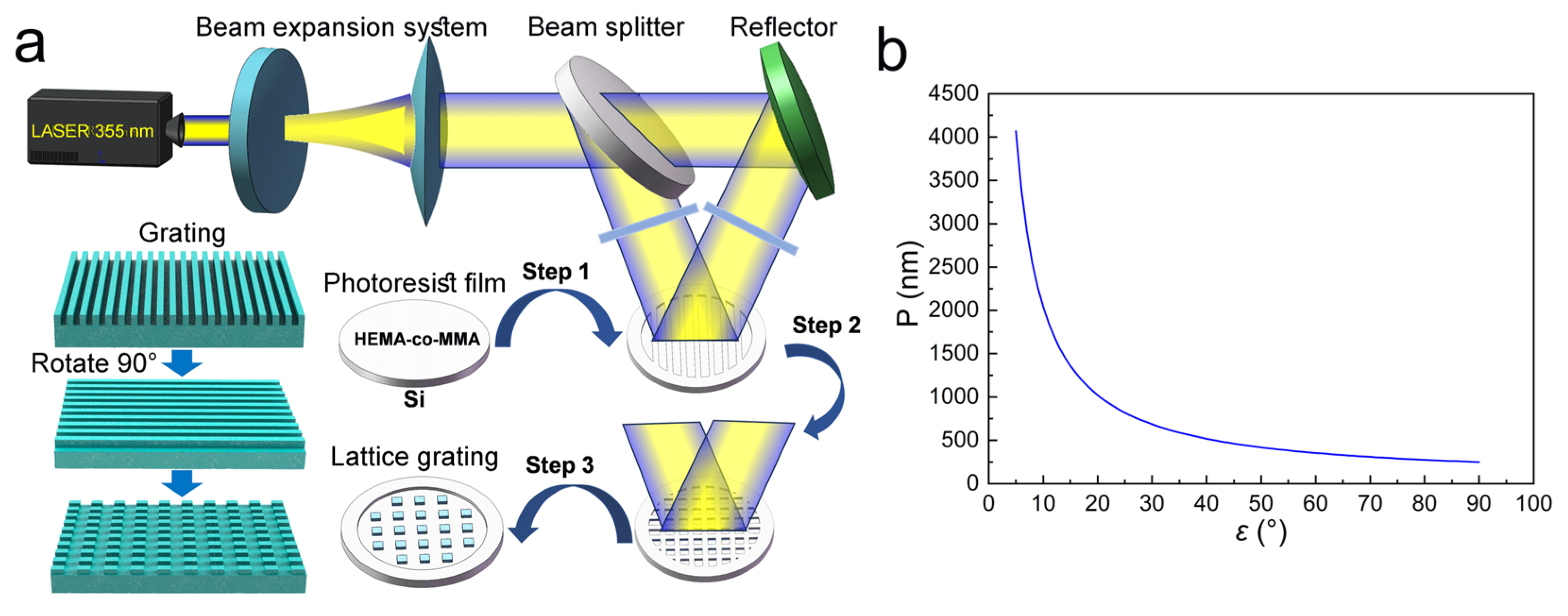

2.3. The Laser Direct Writing Process

2.4. Measurement and Characterization

3. Results

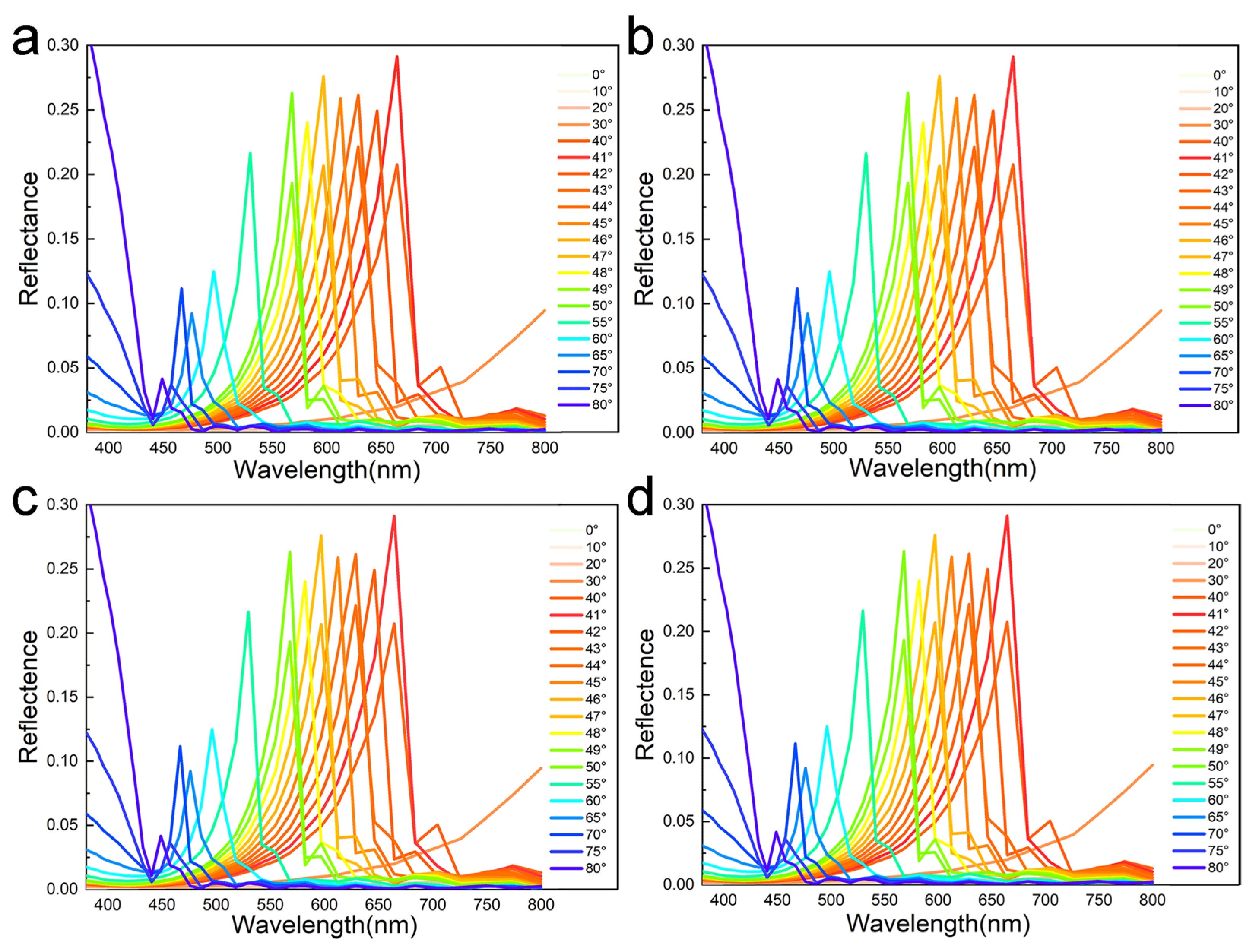

3.1. Processing Design and Simulation

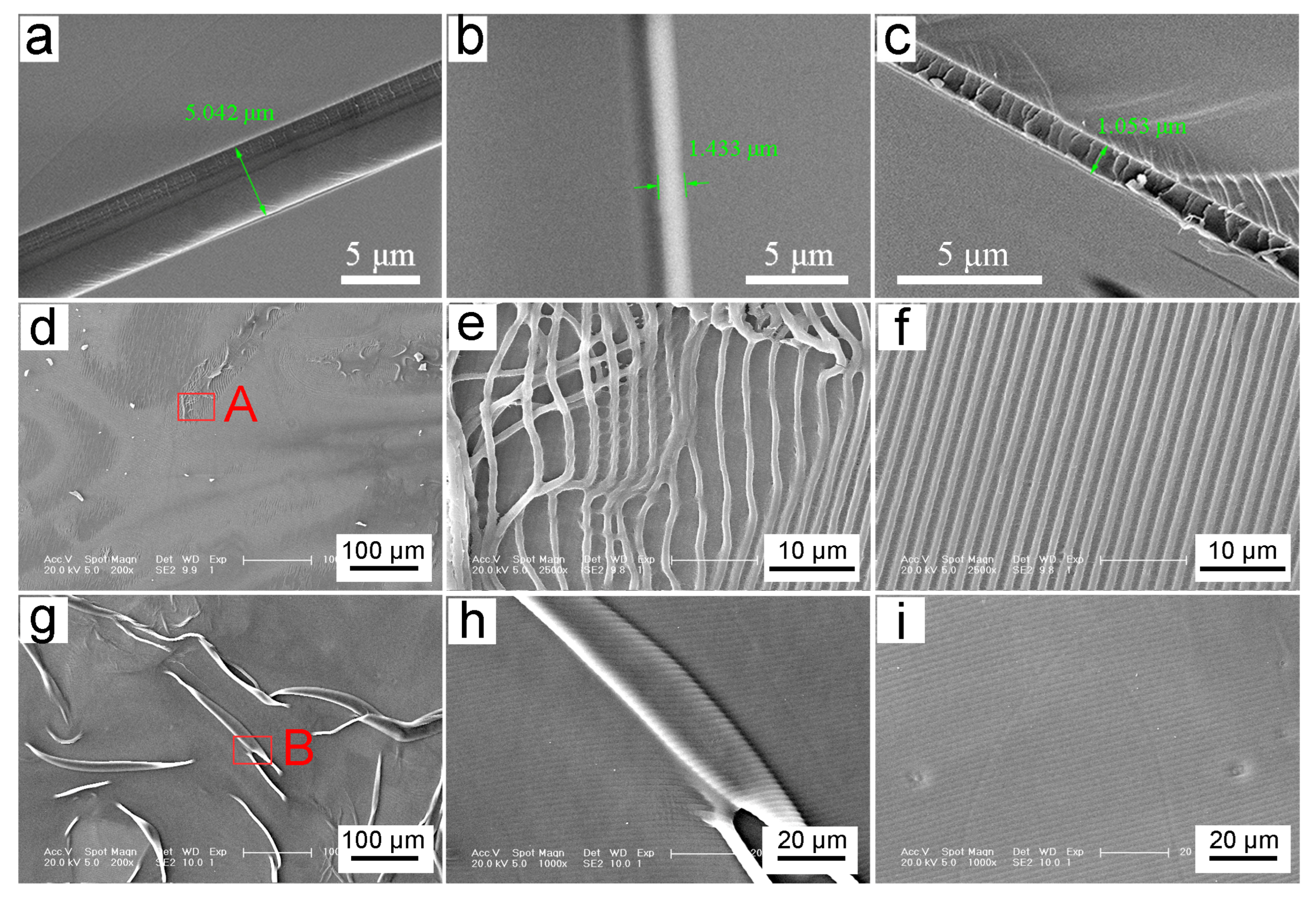

3.2. Fabrication of Nanostructured Gratings

3.3. Nanomechanical and Optical Properties of Nanostructured Gratings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arora, E.K.; Sharma, V.; Sethi, G.; Puthanagady, M.S.; Meena, A. Bioinspired designer surface nanostructures for structural color. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, R.K.; Ren, J.; Zhang, S.F.; Wu, S.L. Bioinspired dynamic camouflage in programmable thermochromic-patterned photonic films for sophisticated anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2210047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäthger, L.M.; Denton, E.J.; Marshall, N.J.; Hanlon, R.T. Mechanisms and behavioural functions of structural coloration in cephalopods. J. R Soc. Interface 2009, 6 (Suppl. 2), S149–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssier, J.; Saenko, S.V.; Van Der Marel, D.; Milinkovitch, M.C. Photonic crystals cause active colour change in chameleons. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, M.A.; Chen, P.Y.; Lin, A.Y.M.; Seki, Y. Biological materials: Structure and mechanical properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008, 53, 1–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Othman, M.B.H.; Javed, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Akil, H.M. Classification, processing and application of hydrogels: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 57, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Le, X.X.; Zhou, S.Y.; Chen, T. Recent progress in smart polymeric gel-based information storage for anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2201262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Le, X.X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, T. Stimulus-responsive polymer materials toward multi-mode and multi-level information anti-counterfeiting: Recent advances and future challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.T.; Ren, Q.; Vogelbacher, F.; Sha, W.E.I.; Hou, X.Y.; Yao, X.; Song, Y.L.; Li, M.Z. Bioinspired quasi-3D multiplexed anti-counterfeit imaging via self-assembled and nanoimprinted photonic architectures. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Yan, S.S.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.T.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Li, J.Y.; Wen, L.Y. Scalable multistep imprinting of multiplexed optical anti-counterfeiting patterns with hierarchical structures. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 13638–13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.L.; Liu, X.P.; Liu, X.C.; Wu, J.Y.; Lin, W.J.; Lin, X.F.; Yi, G.B. Unclonable anti-counterfeiting labels based on plasmonic-patterned nanostructures. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24, 2101701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.W.; Zhang, H.Y.; Yu, J.H. Luminescence anti-counterfeiting: From elementary to advanced. Aggregate 2021, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Jin, X.F.; Wang, M.Y.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, J.Y.; Zhang, J.C.; Wang, Z.F. Multimode dynamic photoluminescent anticounterfeiting and encryption based on a dynamic photoluminescent material. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Tang, L.H.; Wang, J.J.; Liu, X.J.; Ying, Y.B. Multidimensional SERS barcodes on flexible patterned plasmonic metafilm for anticounterfeiting applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016, 4, 1475–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Rijckaert, H.; Zeng, M.; Haustraete, K.; Laforce, B.; Vincze, L.; Driessche, V.I.; Kaczmarek, M.A.; Deun, V.R. Simultaneously excited downshifting/upconversion luminescence from lanthanide-doped core/shell fluoride nanoparticles for multimode anticounterfeiting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1707365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Yuan, Z.K.; Chen, X.D. Structural color materials for optical anticounterfeiting. Small 2020, 16, 1907626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Mamaqani, R.; Razavi, B.; Kalajahi, S.M. Photoluminescent and chromic nanomaterials for anticounterfeiting technologies: Recent advances and future challenges. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 14417–14492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, R.; Suzuki, T.; Shimobaba, T.; Shiraki, A.; Naruse, M.; Nakayama, H.; Kakue, T.; Ito, T. Inkjet printing-based volumetric display projecting multiple full-colour 2D patterns. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Rong, F.; Gu, H.; Xie, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Z. Bioinspired angle-independent photonic crystal colorimetric sensing. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5331–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyubchanskii, I.L.; Dadoenkova, N.N.; Lyubchanskii, M.I.; Shapovalov, E.A.; Rasing, T. Magnetic photonic crystals. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2003, 36, R277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yang, M.; Huang, J.; Yu, D.; Hong, W.; Chen, X. Freestanding graphitic carbon nitride photonic crystals for enhanced photocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 4943–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yethiraj, A.; Thijssen, J.H.J.; Wouterse, A.; Blaaderen, V.A. Large-area electric-field-induced colloidal single crystals for photonic applications. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Chen, C.B.; Yang, D.F. Applications of inverse opal photonic crystal hydrogels in the preparation of acid–base color-changing materials. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 2243–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Fan, J.R.; Chen, Z.J.; Chen, X.Y.; Jin, S.X.; Wu, W.G. Plasmonic color generation and refractive index sensing with three-dimensional air-gap nanocavities. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 6283–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagor, D.W.; Butko, V.Y. Highly conductive nanolayers on strontium titanate produced by preferential ion-beam etching. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Herman, P.R. Laser scanning holographic lithography for flexible 3D fabrication of multi-scale integrated nano-structures and optical biosensors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.C.; Chen, H.L. Nanoimprint technology for patterning functional materials and its applications. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 132, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Kiravittaya, S.; Harazim, S.; Schmidt, O.G. Principles and applications of micro and nanoscale wrinkles. Mat. Sci. Eng. R 2010, 70, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Xie, D.; Shen, H.Y.; Li, F.Y.; Chen, J.J. Functional micro–nano Structure with variable colour: Applications for anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Polymol. Tech. 2019, 2019, 6519018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.I.; Park, B.J.; Ma, Z.; Choi, J.; Ju, B.K. Nanopatterning by laser interference lithography: Applications to optical devices. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 1521–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.P.; Zhou, Y.M.; Chen, G.X.; Xiao, K.D.; Lu, J. Materials vs. digits: A review of embedded anti-counterfeiting fingerprints in three-dimensional printing. Mat. Sci. Eng. R 2024, 160, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.L.; Ding, H.B.; Chong, Z.J.; Zeng, Y.; Niu, Y.F.; Zhang, J.N.; Kang, Y.; Du, X.; Gu, Z. Direct laser writing photonic crystal hydrogel sensors for in-situ sensing in microfluidic device. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Hu, Y.B.; Jiang, N.; Montelongo, Y.; Richardson, A.; Blyth, J.; Yetisen, A.K. Reversible photonic hydrogel sensors via holographic interference lithography. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 207, 114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Butt, H.; Montelongo, Y.; Liu, F.; Afewerki, S.; Ying, G.L.; Dai, Q.; Yun, S.H.; Yetisen, A.K. Laser interference lithography for the nanofabrication of stimuli-responsive bragg stacks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1702715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.R.; Qiao, Z.; Liao, Y.K.; Zhu, S.; Shi, L.; Kim, M.; Chen, Y.C. Enzyme-programmable microgel lasers for information encoding and anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2107809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Q.; Hou, X.; Du, C.; Wang, X.; Gao, D. Recent advances in the anti-counterfeiting applications of long persistent phosphors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 17759–17768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Xie, G.X.; Luo, J.B. Mechanical properties of nanoparticles: Basics and applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 47, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Miao, W.S.; Zhang, Y.D.; Gao, H.J.; Hui, D. Mechanical properties of nanomaterials: A review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2020, 9, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.P.; Wu, S.L.; Tang, B.T.; Ma, W.; Zhang, S.F. Structurally colored polymer films with narrow stop band, high angle-dependence and good mechanical robustness for trademark anti-counterfeiting. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 14755–14762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.K.; Qiu, X.Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, P.; Guo, Q.Q.; Zhang, X.X. Multi-modal melt-processing of birefringent cellulosic materials for eco-friendly anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2407170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wu, J.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J.; Yao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Hayasaki, Y.; Zhang, H. Femtosecond-laser preparation of hydrogel with micro/nano-structures and their biomedical applications. Small Sci. 2025, 5, 2400400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.; Brahim, S.; Ishihara, K.; Guiseppi, E.A. Molecularly engineered p (HEMA)-based hydrogels for implant biochip biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 4767–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.S.; Tang, Z.H.; Tang, X.G.; Liang, Z.H.; Feng, J.S.; Ye, L.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lan, M.; Zhu, D.; et al. Wireless wearable system based on multifunctional conductive PEG-HEMA hydrogel with anti-freeze, anti-UV, self-healing, and self-adhesive performance for health monitoring. Colloid. Surf. A 2024, 695, 134196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggat, P.A.; Smith, D.R.; Kedjarune, U. Surgical applications of methyl methacrylate: A review of toxicity. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2009, 64, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aflalo, K.; Gao, P.; Trivedi, V.; Sanjeev, A.; Zalevsky, Z. Optical super-resolution imaging: A review and perspective. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 183, 108536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.D.; Britten, J.A.; Decker, D.E.; Shore, B.W.; Stuart, B.C.; Perry, M.D.; Li, L. High-efficiency metallic diffraction gratings for laser applications. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Tu, D.F.; Li, H.X.; Huang, K.X.; Shi, Y.H.; Hu, Z.X.; Liang, L.; Sun, J.Y. Fundamental nanostructures obtained by hydrogel photoresist in laser processing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Manipulation, Manufacturing and Measurement on the Nanoscale (3M-NANO), Zhongshan, China, 29 July 2024–2 August 2024; pp. 315–319. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10769716 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Chuang, Y.J.; Tseng, F.G.; Cheng, J.H.; Lin, W.K. A novel fabrication method of embedded micro-channels by using SU-8 thick-film photoresists. Sensor Actuat. A-Phys. 2003, 103, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Park, M.B.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.H.; Yue, C.Y. Fabrication of large SU-8 mold with high aspect ratio microchannels by UV exposure dose reduction. Sensor Actuat. B-Chem. 2004, 101, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.G.; Lin, W.X.; Hong, M.H. Surface coloring by laser irradiation of solid substrates. APL Photonics 2019, 4, 051101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marteau, J.; Bigerelle, M. Toward an understanding of the effect of surface roughness on instrumented indentation results. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 7239–7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutua, J.; Nakata, S.; Onda, T.; Chen, Z.C. Optimization of selective laser melting parameters and influence of post heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of maraging steel. Mater. Des. 2018, 139, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Farris, R.J. Influence of processing conditions on the thermal and mechanical properties of SU8 negative photoresist coatings. J. Micomech. Microeng. 2002, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroe, W.W. Improvements and Effects of Thermal History on Mechanical Properties for Polymer Selective Laser Sintering (SLS). Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Y.; Bhushan, B. Structure and mechanical properties of beetle wings: A review. Rsc. Adv. 2012, 2, 12606–12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, W.; Deng, Q.; Shi, Y.; Sun, J. Nanomechanical and Optical Properties of Anti-Counterfeiting Nanostructures Obtained by Hydrogel Photoresist in Laser Processing. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120829

Wu W, Deng Q, Shi Y, Sun J. Nanomechanical and Optical Properties of Anti-Counterfeiting Nanostructures Obtained by Hydrogel Photoresist in Laser Processing. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(12):829. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120829

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Wei, Qingxue Deng, Yuhang Shi, and Jiyu Sun. 2025. "Nanomechanical and Optical Properties of Anti-Counterfeiting Nanostructures Obtained by Hydrogel Photoresist in Laser Processing" Biomimetics 10, no. 12: 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120829

APA StyleWu, W., Deng, Q., Shi, Y., & Sun, J. (2025). Nanomechanical and Optical Properties of Anti-Counterfeiting Nanostructures Obtained by Hydrogel Photoresist in Laser Processing. Biomimetics, 10(12), 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120829