Toward Smart VR Education in Media Production: Integrating AI into Human-Centered and Interactive Learning Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Structured synthesis: A systematic scoping review of 94 studies (2013–2024) spanning immersive platforms, AI components, and interaction modalities;

- Human-centered perspective: Connecting learner modeling, adaptive feedback loops, and teacher-in-the-loop orchestration to concrete media-production workflows;

- Evaluation toolkit: Identifying common outcome domains and assessment instruments to support comparability across future studies.

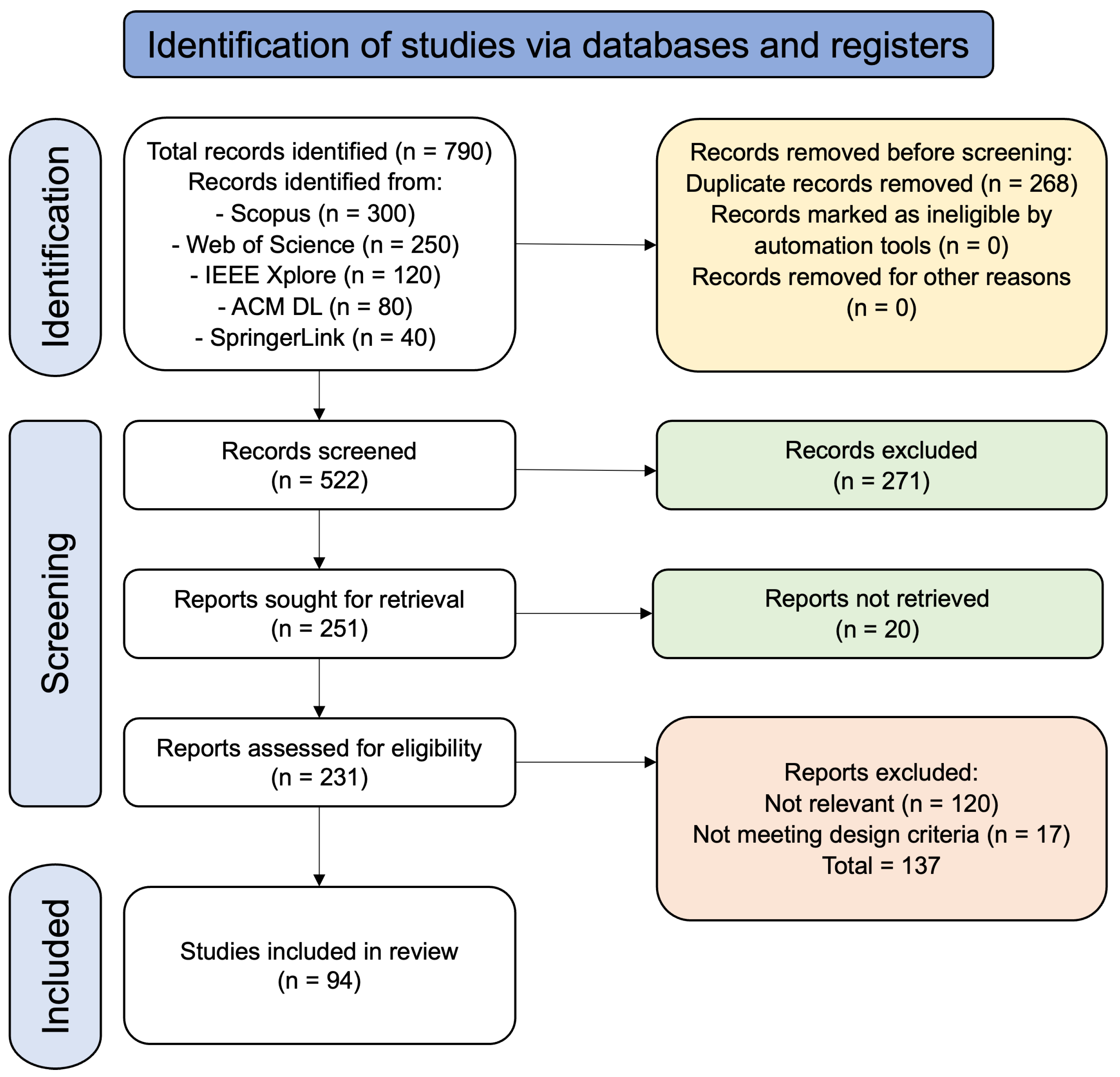

2. Review Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

- “virtual reality” OR “immersive learning” OR “3D simulation”;

- “artificial intelligence” OR “adaptive learning” OR “machine learning”;

- “human-centered” OR “human-in-the-loop” OR “interactive systems”;

- “media production” OR “television education” OR “video editing training”.

- "virtual reality" AND "artificial intelligence" AND

- ("human-centered" OR "human-in-the-loop") AND

- ("media production" OR "television" OR "broadcasting" OR "video editing")

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Described VR-based or AI-enhanced educational systems;

- Addressed media production or closely related creative-technology domains (e.g., studio operations, directing, cinematography, editing, VFX, audio, broadcasting);

- Incorporated human-centered and/or interactive design (e.g., learner modeling, multimodal interaction, teacher-in-the-loop orchestration);

- Appeared in peer-reviewed venues (journals, conferences, or scholarly book chapters);

- Reported empirical findings, technical prototypes, or conceptual frameworks relevant to intelligent immersive education.

- Applied VR or AI outside education or without an educational intent (e.g., entertainment, clinical therapy);

- Focused solely on conventional e-learning without immersive/interactive features;

- Lacked sufficient detail on system design or learner interaction mechanisms;

- Were not available in full text or were published in languages other than English.

2.3. Screening and Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Coding

2.5. Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Synthesis and Reporting

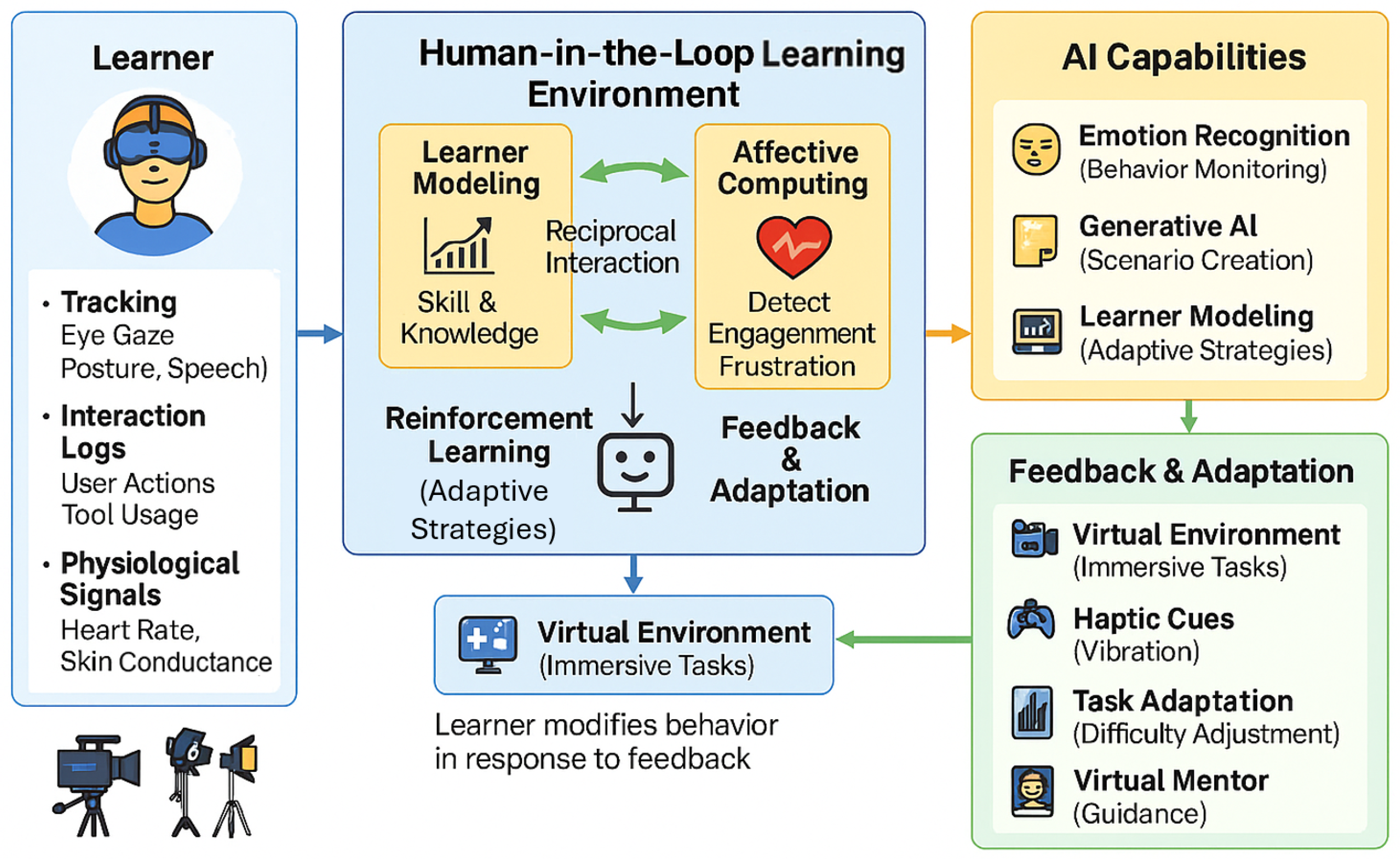

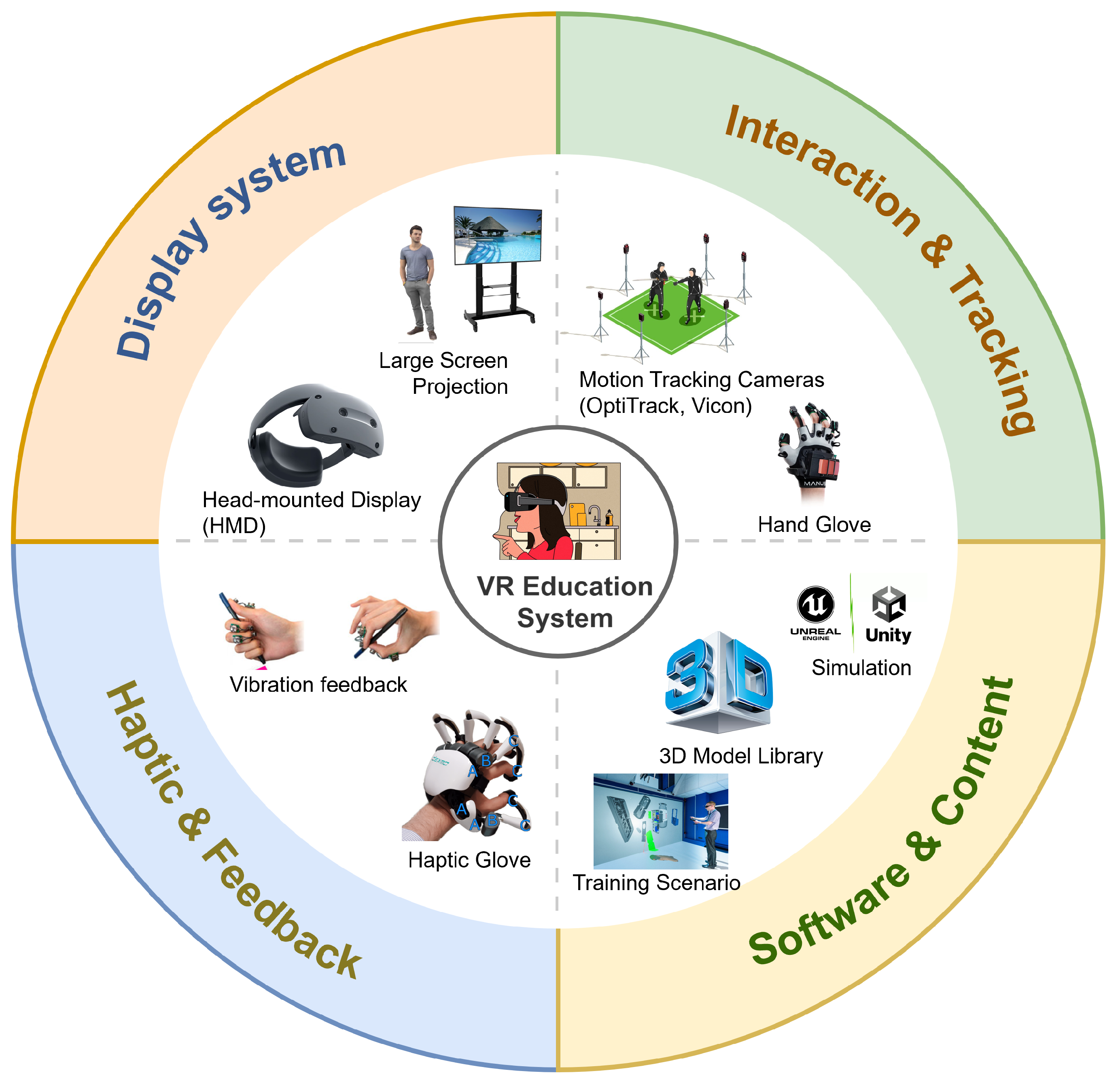

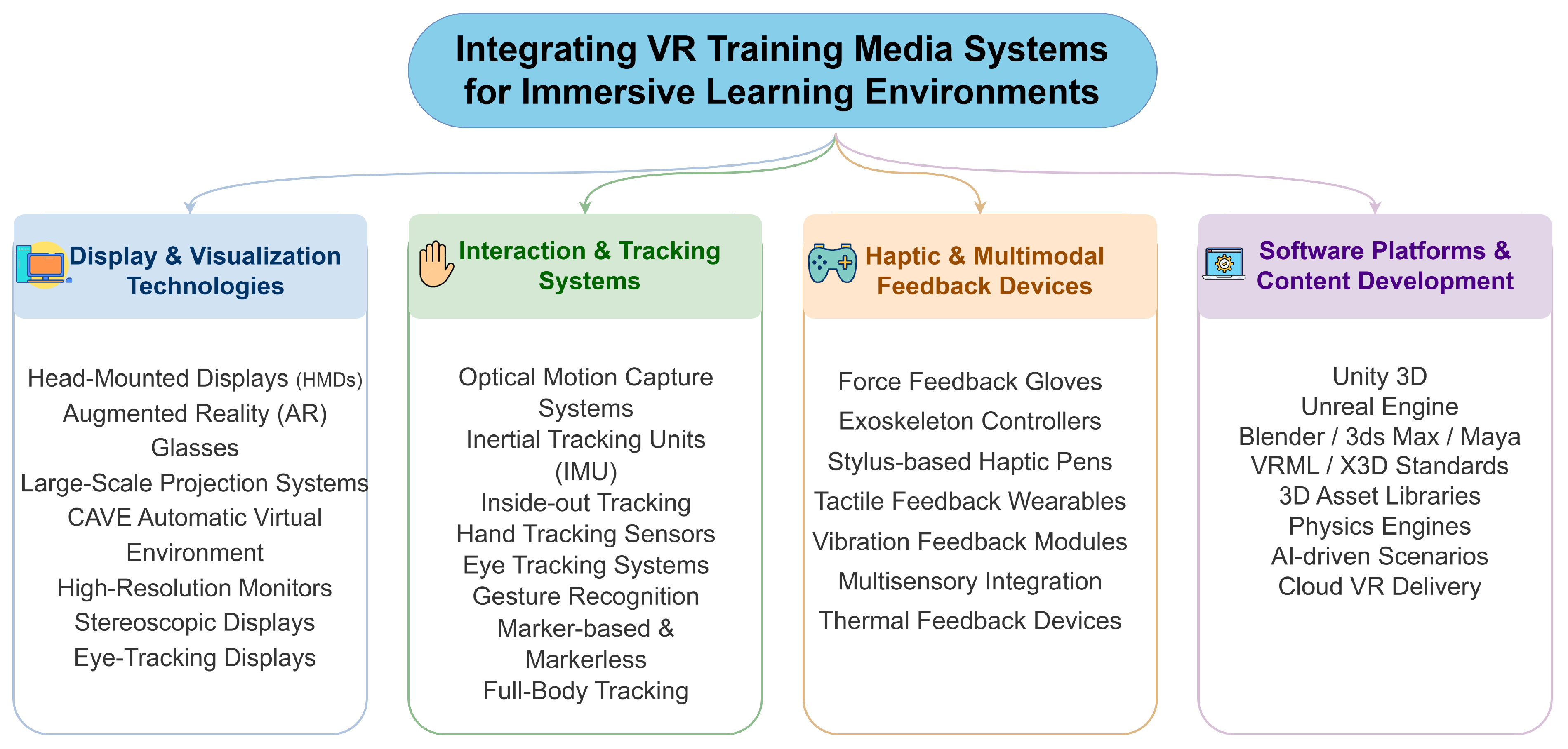

2.7. Core Components of the VR-Based Training Framework

- Display system: Head-mounted displays (HMDs), large projection screens, and CAVE-like environments that simulate professional studio settings.

- Interaction and tracking module: Motion capture systems, VR controllers, gesture-recognition gloves, and optical or inside-out tracking for naturalistic interaction with virtual tools.

- Haptic and feedback module: Haptic pens, force-feedback gloves, and vibration actuators that provide tactile cues and enhance task realism.

- Software and content module: 3D modeling tools, game engines (e.g., Unity, Unreal Engine), and scenario-specific training environments.

3. Background and Conceptual Foundations

3.1. Media Production Education: Needs and Characteristics

3.2. Human-Centered Learning in Virtual Reality

3.3. Artificial Intelligence in Learning Environments

4. Research Landscape: Smart VR Education Systems

4.1. Immersive VR Platforms in Media Production Training

4.2. AI-Augmented Interaction and Adaptation

4.3. Learner Modeling and Feedback Loops

5. Benefits and Educational Impacts

6. Challenges and Limitations

Design Principles for Smart VR in Media Production.

|

7. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| HITL | Human-in-the-Loop |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| UI | User Interface |

| UX | User Experience |

References

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Z.; Goetz, E.T.; Cifuentes, L.; Keeney-Kennicutt, W.; Davis, T.J. Effectiveness of virtual reality-based instruction on students’ learning outcomes in K-12 and higher education: A meta-analysis. Comput. Educ. 2014, 70, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.; Langlotz, T.; Zollmann, S. 6dive: 6 degrees-of-freedom immersive video editor. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 2, 676895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; DiVerdi, S.; Hertzmann, A.; Liu, F. Vremiere: In-headset virtual reality video editing. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 5428–5438. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, F.; Wang, H.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. A high-density EEG study investigating VR film editing and cognitive event segmentation theory. Sensors 2021, 21, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellas, N.; Mystakidis, S.; Kazanidis, I. Immersive Virtual Reality in K-12 and Higher Education: A systematic review of the last decade scientific literature. Virtual Real. 2021, 25, 835–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Janczewski, N.; Kraus, J.; Engeln, A.; Baumann, M. A subjective one-item measure based on NASA-TLX to assess cognitive workload in driver-vehicle interaction. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 86, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, N.; Penalver-Andres, J.; Buetler, K.A.; Nef, T.; Müri, R.M.; Marchal-Crespo, L. Effect of immersive visualization technologies on cognitive load, motivation, usability, and embodiment. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.E. Evidence-based principles for how to design effective instructional videos. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2021, 10, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Qi, W.; Ovur, S.E.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Su, H.; Ferrigno, G.; De Momi, E. A novel muscle-computer interface for hand gesture recognition using depth vision. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 5569–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Schmirander, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Ferrigno, G.; De Momi, E. Bilateral teleoperation control of a redundant manipulator with an rcm kinematic constraint. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 4477–4482. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Sha, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Jin, Y.; Gašević, D. Practical and ethical challenges of large language models in education: A systematic scoping review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizani, S.; Mazhar, T.; Shahzad, T.; Ahmad, W.; Bibi, A.; Hamam, H. A systematic literature review to implement large language model in higher education: Issues and solutions. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Bai, J.; Xu, T.; Zhou, Y. Large language models in education: A systematic review. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Computer Science and Technologies in Education (CSTE), Xi’an, China, 19–21 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Li, G.; Feng, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zuo, M. Virtual reality in K-12 and higher education: A systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2019. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021, 37, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudoniene, D.; Rutkauskiene, D. Virtual and augmented reality in education. Balt. J. Mod. Computing. 2019, 7, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Sheiban, F.J.; Qi, W.; Ovur, S.E.; Alfayad, S. A bioinspired virtual reality toolkit for robot-assisted medical application: Biovrbot. IEEE Trans.-Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2024, 54, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Multimedia Learning, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Multimedia learning. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 41, pp. 85–139. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oje, A.V. Evidence-Based Design and Pedagogical Principles for Optimizing the Educational Benefits of Virtual Reality Learning Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Taranilla, R.; Tirado-Olivares, S.; Cózar-Gutiérrez, R.; González-Calero, J.A. Effects of virtual reality on learning outcomes in K-6 education: A meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 35, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strojny, P.; Dużmańska-Misiarczyk, N. Measuring the effectiveness of virtual training: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2023, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, H.; Mortimer, M.; Horan, B. Evaluating the effectiveness of virtual reality for safety-relevant training: A systematic review. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 2839–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Kablitz, D.; Schumann, S. Learning effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in education and training: A systematic review of findings. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2024, 4, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.; Sitzmann, V.; Ruiz-Borau, J.; Wetzstein, G.; Gutierrez, D.; Masia, B. Movie editing and cognitive event segmentation in virtual reality video. ACM Trans. Graph. 2017, 36, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, A.A.; Al Rifaee, M.M. A Systematic Review of the use of Virtual Reality in Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on information technology (ICIT), Amman, Jordan, 9–10 August 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer, N.; van der Werf, V.; Brinkman, W.P.; Specht, M. Virtual reality and collaborative learning: A systematic literature review. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1159905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozioko, O.; Dahiya, R. Smart tactile gloves for haptic interaction, communication, and rehabilitation. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jeon, C.; Kim, J. A study on immersion and presence of a portable hand haptic system for immersive virtual reality. Sensors 2017, 17, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchierotti, C.; Sinclair, S.; Solazzi, M.; Frisoli, A.; Hayward, V.; Prattichizzo, D. Wearable Haptic Systems for the Fingertip and the Hand: Taxonomy, Review, and Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2017, 10, 580–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhanom, I.B.; MacNeilage, P.; Folmer, E. Eye tracking in virtual reality: A broad review of applications and challenges. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 1481–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailenko, M.; Maksimenko, N.; Kurushkin, M. Eye-tracking in immersive virtual reality for education: A review of the current progress and applications. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 697032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlon, Y.; Hu, W.; Nakatani, M.; Maurya, S.; Oki, T.; Zhu, J.; Fujii, H. Immersive gaze sharing for enhancing education: An exploration of user experience and future directions. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2024, 5, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M. Immersion and the illusion of presence in virtual reality. Br. J. Psychol. 2018, 109, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Seijo, S.; Vicente, P.N.; López-García, X. Immersive journalism: The effect of system immersion on place illusion and co-presence in 360-degree video reporting. Systems 2022, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.M. Presence in Virtual Reality and Everyday Life: Immersion within a World of Representation. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2016, 25, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, M.; Brantley, S.; Feng, J. A mini review of presence and immersion in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Baltimore, MD, USA, 3–8 October 2021; SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Volume 65, pp. 1099–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M. Six views of embodied cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2002, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded Cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G.; Petersen, G.B. The Cognitive Affective Model of Immersive Learning (CAMIL): A theoretical research-based model of learning in immersive virtual reality. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerald, J. The VR Book: Human-Centered Design for Virtual Reality; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Makransky, G.; Lilleholt, L. A structural equation modeling investigation of the emotional value of immersive virtual reality in education. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, L.; Dau, S.; Davidsen, J. Designing for collaborative learning in immersive virtual reality: A systematic literature review. Virtual Real. 2024, 28, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. AI and Education: Guidance for Policy-Makers; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fouché, G.; Argelaguet Sanz, F.; Faure, E.; Kervrann, C. Timeline design space for immersive exploration of time-varying spatial 3d data. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Tsukuba, Japan, 29 November–1 December 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, T.; Sehad, N.; Nadir, Z.; Song, J. VR-based immersive service management in B5G mobile systems: A UAV command and control use case. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 5349–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergroth, J.D.; Koskinen, H.M.; Laarni, J.O. Use of immersive 3-D virtual reality environments in control room validations. Nucl. Technol. 2018, 202, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Su, H.; Ma, G.; Liu, X. A novel dual-modal emotion recognition algorithm with fusing hybrid features of audio signal and speech context. Complex Intell. Syst. 2023, 9, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haataja, E.; Salonen, V.; Laine, A.; Toivanen, M.; Hannula, M.S. The relation between teacher-student eye contact and teachers’ interpersonal behavior during group work: A multiple-person gaze-tracking case study in secondary mathematics education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Harter, D. Multi-sensor eye-tracking systems and tools for capturing student attention and understanding engagement in learning: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 22402–22413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, K.; McLaren, B.M.; Aleven, V. Co-designing a real-time classroom orchestration tool to support teacher-AI complementarity. Grantee Submiss. 2019, 6, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, L. Eye tracking methodology; theory and practice. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2007, 10, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, K.; Nyström, M.; Andersson, R.; Dewhurst, R.; Jarodzka, H.; Van de Weijer, J. Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodotzki, J.; Müller, B.T.; Tekkaya, A.E. Enhancing the Immersion of Augmented Reality through Haptic Feedback. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Technologies & Education, Helsinki, Finland, 5–7 March 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, D.; Baek, Y.; Cho, M.; Park, S.; Sagar, A.S.; Kim, H.S. Low-latency haptic open glove for immersive virtual reality interaction. Sensors 2021, 21, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, Q.; He, T.; Liu, H.; Chen, T.; Lee, C. Haptic-feedback smart glove as a creative human-machine interface (HMI) for virtual/augmented reality applications. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M.F.; Tan, C.W. Aligning crowd-sourced human feedback for reinforcement learning on code generation by large language models. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, T.; Friedmann, F.; Regenbrecht, H. The Experience of Presence: Factor Analytic Insights. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2001, 10, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Li, D. A review study on eye-tracking technology usage in immersive virtual reality learning environments. Comput. Educ. 2023, 196, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Liu, R.; Sokolikj, Z.; Dahlstrom-Hakki, I.; Israel, M. Using eye-tracking in education: Review of empirical research and technology. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 1383–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchowski, A.T. Gaze-based interaction: A 30 year retrospective. Comput. Graph. 2018, 73, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Su, H.; Aliverti, A. A smartphone-based adaptive recognition and real-time monitoring system for human activities. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2020, 50, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Xu, X.; Qian, K.; Schuller, B.W.; Fortino, G.; Aliverti, A. A review of AIoT-based human activity recognition: From application to technique. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 29, 2425–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Aliverti, A. A multimodal wearable system for continuous and real-time breathing pattern monitoring during daily activity. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2019, 24, 2199–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fineman, B.; Lewis, N. Securing your reality: Addressing security and privacy in virtual and augmented reality applications. EDUCAUSE Review (Online), 21 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, A.; Ramachandra, R.; Venkatesh, S.; Prasanna, S.M. Biometrics in extended reality: A review. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Rajvanshi, S.; Kaur, G. Privacy and security concerns with augmented reality/virtual reality: A systematic review. In Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Special Education; Scrivener Publishing: Beverly, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Abid, N. A Review of Security and Privacy Challenges in Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Systems with Current Solutions and Future Directions. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 2023, 3, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hajj, M. Cybersecurity and Privacy Challenges in Extended Reality: Threats, Solutions, and Risk Mitigation Strategies. Virtual Worlds 2024, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tong, W.; Wei, Z.; Xia, M.; Lee, L.H.; Qu, H. Cinematography in the metaverse: Exploring the lighting education on a soundstage. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Shanghai, China, 25–29 March 2023; IEEE: Ney York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 571–572. [Google Scholar]

- Bareišytė, L.; Slatman, S.; Austin, J.; Rosema, M.; van Sintemaartensdijk, I.; Watson, S.; Bode, C. Questionnaires for evaluating virtual reality: A systematic scoping review. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 16, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A ’Quick and Dirty’ Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., McClelland, I.L., Weerdmeester, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, K.; Hong, G.; Tegene, M.; McLaren, B.M.; Aleven, V. The classroom as a dashboard: Co-designing wearable cognitive augmentation for K-12 teachers. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, Sydney, Australia, 7–9 March 2018; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, U.S.; Al-Baghli, R. Ethical concerns in contemporary virtual reality and frameworks for pursuing responsible use. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1451273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukshinov, E.; Tu, J.; Szita, K.; Senthil Nathan, K.; Nacke, L.E. Widespread yet unreliable: A systematic analysis of the use of presence questionnaires. Interact. Comput. 2025, Iwae064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Ngo, H.N.; Hong, Y.; Dang, B.; Nguyen, B.P.T. Ethical principles for artificial intelligence in education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 4221–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, H.; Shum, S.B.; Chen, G.; Conati, C.; Tsai, Y.S.; Kay, J.; Knight, S.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Sadiq, S.; Gašević, D. Explainable artificial intelligence in education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Ma, W.; Hu, Y.; Bi, X. The who, why, and how of ai-based chatbots for learning and teaching in higher education: A systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 7781–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nee, C.K.; Rahman, M.H.A.; Yahaya, N.; Ibrahim, N.H.; Razak, R.A.; Sugino, C. Exploring the trend and potential distribution of chatbot in education: A systematic review. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2023, 13, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Daniel, B.K. Transforming language education: A systematic review of AI-powered chatbots for English as a foreign language speaking practice. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Götz, G.; Molerov, D.; Narciss, S.; Neuhaus, C.; et al. ChatGPT for Good? On Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, C.W.; Ade-Ibijola, A. Chatbots applications in education: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhail, M.A.; Alturki, N.; Alramlawi, S.; Alhejori, K. Interacting with educational chatbots: A systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 973–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debets, T.; Banihashem, S.K.; Joosten-Ten Brinke, D.; Vos, T.E.; de Buy Wenniger, G.M.; Camp, G. Chatbots in education: A systematic review of objectives, underlying technology and theory, evaluation criteria, and impacts. Comput. Educ. 2025, 234, 105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amershi, S.; Cakmak, M.; Knox, W.B.; Kulesza, T. Power to the People: The Role of Humans in Interactive Machine Learning. AI Mag. 2014, 35, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Xu, X.; Lee, L.H.; Tong, W.; Qu, H.; Hui, P. Feeling present! from physical to virtual cinematography lighting education with metashadow. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 1127–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Tan, C.W. From code generation to software testing: AI Copilot with context-based RAG. IEEE Softw. 2025, 42, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tong, W.; Wei, Z.; Xia, M.; Lee, L.H.; Qu, H. Transforming cinematography lighting education in the metaverse. Vis. Inform. 2025, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, K.; Doroudi, S. Equity and Artificial Intelligence in Education: Will “AIEd” Amplify or Alleviate Inequities in Education? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principle | Theoretical Basis | Application in VR Design | Media-Production Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embodied Cognition | [40,41] | Motion-based interaction; spatial manipulation | Gesture-controlled camera blocking; light-stand positioning in 3D sets |

| Learner Agency | [42,43] | Free navigation; branching scenarios; sandbox tasks | Director chooses shot-list order and rehearses alternatives |

| Presence & Flow | [38,39] | High-fidelity scenes; minimal UI friction | Realistic control room with low-latency switching practice |

| Affective Feedback | [44,45] | Emotion-adaptive prompts and pacing | Stress-aware rehearsal timing during live-broadcast simulation |

| Social Constructivism | [28,46] | Multi-user co-presence; mentor avatars | Team roles (director, TD, camera) rehearsed in shared VR studio |

| AI Technique | Primary Function | Typical Use in VR Media Training |

|---|---|---|

| Learner Modeling | Profile learner state | Adjusts task difficulty, tool availability, and feedback timing based on interaction logs and progression |

| Emotion Recognition | Detect affective state | Triggers offloading prompts or motivational nudges; escalates challenge under high engagement |

| Reinforcement Learning | Optimize learning path | Learns scenario sequencing and scaffolded exercises for editing/directing tasks |

| NLP Dialogue Agents | Conversational guidance | Answers “why/how” questions; context-aware critique of pacing or lighting |

| Generative AI | Scenario/content generation | Creates scripts, shot lists, or visual inserts aligned with learning objectives |

| Dimension | Metric/Indicator | Method/Tool | Reporting Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | Time-on-task; fixations; scene switches | Eye tracking (e.g., Tobii); interaction logs | Report sampling rate; AOI definition; smoothing/windowing rules. |

| Learning Effectiveness | Pre/post gains; task accuracy | Scenario-based tests; domain rubrics | Report effect direction with mean, SD, n; note task fidelity/rubric. |

| Affective Experience | HRV; frustration detection | Biofeedback; affect models | State sensor placement; window length; features (e.g., RMSSD); classifier type. |

| Usability | SUS [78] | Questionnaire; interviews | Report SUS mean and distribution; summarize major open-coded themes. |

| Collaboration | Turn-taking; coordination | Audio logs; NLP dialogue analysis | Define coding scheme; report inter-rater reliability for discourse labels. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Su, Z.; Tan, T.G.; Chen, L.; Su, H.; Alfayad, S. Toward Smart VR Education in Media Production: Integrating AI into Human-Centered and Interactive Learning Systems. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010034

Su Z, Tan TG, Chen L, Su H, Alfayad S. Toward Smart VR Education in Media Production: Integrating AI into Human-Centered and Interactive Learning Systems. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Zhi, Tse Guan Tan, Ling Chen, Hang Su, and Samer Alfayad. 2026. "Toward Smart VR Education in Media Production: Integrating AI into Human-Centered and Interactive Learning Systems" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010034

APA StyleSu, Z., Tan, T. G., Chen, L., Su, H., & Alfayad, S. (2026). Toward Smart VR Education in Media Production: Integrating AI into Human-Centered and Interactive Learning Systems. Biomimetics, 11(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010034