Abstract

Background: Composite resin veneers have gained popularity due to their affordability and minimally invasive application as biomimetic restorations. However, long-term clinical challenges, such as discoloration, wear, and reduced fracture resistance, necessitate their replacement over time. Ceramic veneers, particularly feldspathic and lithium disilicate, offer superior esthetics and durability, as demonstrated by studies showing their high survival rates and enamel-preserving preparation designs. However, while ceramic veneers survive longer than composite resin veneers, ceramic veneers may need to be removed and replaced. Reports vary for using Er:YAG (erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) lasers for the removal of existing veneers. Methods: A review was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of removing restorative materials with an Er:YAG laser. A clinical study was included, highlighting the conservative removal of aged composite resin veneers using the Er:YAG laser. This method minimizes enamel damage and facilitates efficient debonding. Following laser application, minimally invasive tooth preparation was performed, and feldspathic porcelain veneers were bonded. Results: The review showed positive outcomes whenever the Er:YAG laser was used. In the case study, after a 3-year follow-up, the restorations exhibited optimal function and esthetics. Conclusions: Laser-assisted debonding provides a safe and predictable method for replacing failing composite veneers with ceramic alternatives, aligning with contemporary biomimetic principles.

1. Introduction

The integration of adhesive science with cosmetic dentistry is exemplified particularly well by composite resin veneers [1]. These veneers remain a favored option among many clinicians, especially when restoration is needed for just one or a few teeth—an approach often preferred in areas with limited access to advanced technologies or resources. Typical indications include correcting morphological abnormalities, concealing discolorations, and closing diastemas.

Over time, pH fluctuations, salivary enzymes, and humidity degrade its structure, leading to surface loss, cracks, and discoloration. Complete removal is often unnecessary, as repair preserves tooth structure and minimizes pulpal damage. Adhesion strength depends on surface preparation, composite viscosity, porosity, adhesive system, and restoration timing. A bonding agent facilitates chemical integration between new and existing composite layers [2].

Although composite resin veneers are gaining popularity due to their ability to meet biomimetic esthetic goals while preserving natural tooth structure [3,4], ceramic veneers remain the gold standard for anterior esthetic restorations [5,6]. This is largely because they offer consistently reliable results in terms of form, color, and mechanical properties. Veneers used to close diastemas or correct enamel defects demonstrate survival rates ranging from 74% to 96.3% over periods of 2 to 10 years. Such outcomes depend heavily on precise clinical protocols, careful material selection, and strict compliance with procedural guidelines. Over time, ceramic restorations have demonstrated outstanding success, particularly due to their long-term gloss retention, surface texture, and color stability [7].

Longitudinal outcomes can reach 100% survival rates for mechanical integrity, excellent scores for marginal adaptation, color stability, and excellent periodontal health, with probing depths ≤ 3 mm. It is paramount to address discoloration, gingival architecture, and tooth tissue preservation to successfully use porcelain veneers. For this purpose, a minimally invasive approach using porcelain veneers was planned in this case to preserve enamel, enhancing the bond strength and reducing marginal degradation [8].

Clinicians often face the challenge of replacing composite resin restorations while trying to preserve as much healthy tooth structure as possible, since excessive removal can reduce the tooth’s long-term durability [9,10]. As a result, the dental field is constantly exploring surface pretreatment techniques that can improve bonding effectiveness without damaging the restorative materials. One such method, sandblasting, can enhance adhesion by eliminating surface contaminants and revealing a clean substrate. However, it may also introduce surface and subsurface cracks in the material [11].

A study evaluating the accuracy of different auxiliary devices during the removal of direct composite resin veneers revealed that magnifying loupes enable superior visualization, with precise composite removal and fewer remnants, but also result in greater enamel/dentin loss due to over-preparation. This highlights the trade-off between the elimination of restoration remnants and tissue preservation. Auxiliary ultraviolet lighting did not significantly enhance outcomes compared to conventional methods, likely due to the composite’s fluorescence resembling natural tooth structure. Although electric motors can improve the removal technique, they still produce a trade-off as an unnecessary reduction in sound tooth structure still occurs [12].

The Er:YAG (erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) laser offers several benefits for restoration removal, including its minimally invasive nature, allowing for the selective ablation of restorative materials while protecting healthy tooth structure. It also ensures thermal safety by keeping the rise in intrapulpal temperature below the critical 5.5 °C threshold, thereby avoiding potential pulp damage. Additionally, the laser provides efficient performance, with the ability to debond veneers in as little as 20 s, depending on their thickness, often surpassing the effectiveness of ultrasonic techniques [13].

The parameters for the removal of composite resin veneers are an adaptation from scenarios of the more well-published removal of ceramic veneers or the ablation of tooth hard tissues. Considering that there are limited reports showing the benefits of removing composite veneers with the Er:YAG laser, this article conducts a narrative review on the use of the Er:YAG laser as a safe, conservative alternative for the removal of composite resin restorations, with minimal side effects; this article highlights a case report presenting the steps for replacing composite resin veneers with porcelain veneers, using Er:YAG laser ablation, from treatment planning to a 3-year follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

Articles published between January 2010 and January 2025 on the removal of restorations using an Er:YAG laser were searched in PubMed and Google Scholar. The following search strategy was used in PubMed: ((((Er:YAG laser) AND (composite resin veneers)) OR (ceramic veneers))) AND (laser debonding). The search in PubMed initially yielded a total of 31 articles. After an initial reading of the titles and the abstracts, seventeen articles were selected. Then, one article was excluded (a systematic review), and another article was excluded because it evaluated another type of laser, resulting in fifteen articles. For the Google Scholar search, the following keywords were used: “Er:YAG”, “Erbium Laser”, and “Debonding”.

As of January 2025, the Google Scholar search resulted in 174 articles. The following terms were used for the search: Er:YAG laser; composite resin veneers, ceramic veneers, minimally invasive dentistry; and laser debonding. After reading the titles and abstracts, one hundred and fifty-seven articles were excluded. From the seventeen selected articles, 3 articles were about other types of lasers, 1 article was a short communication, 1 reference was a book, 4 articles were about other subjects, 1 article used bovine teeth, and 1 article was repeated. This resulted in four articles selected. A further manual search was conducted on the references of the previous 20 articles, adding 7 more articles. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. Letters, books, book chapters, literature reviews, and articles with full text not available were excluded from this review. Only publications addressing the benefits of using an Er:YAG laser for the removal of resin composite veneers or other bonded restorative material were analyzed.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the search performed.

2.2. Case Report

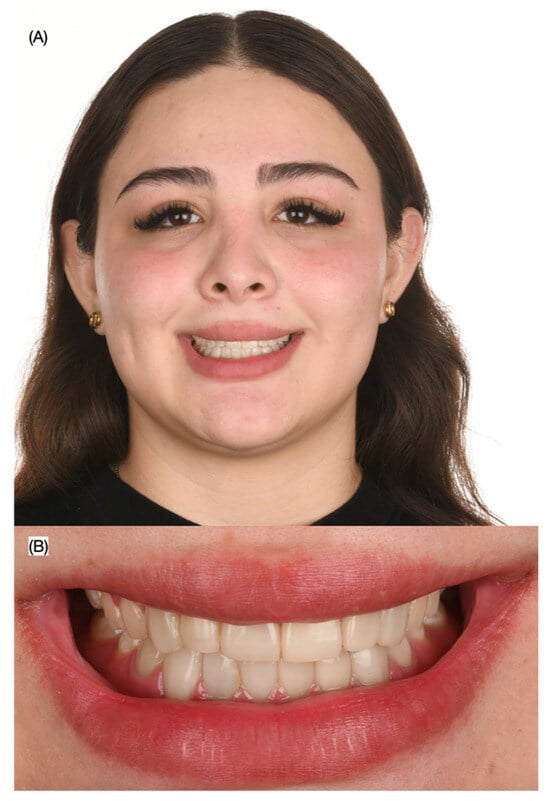

A 30-year-old female patient presented to the clinic with the chief complaint of wanting to improve her smile. The patient was reported to have had direct resin composite veneers from the maxillary right first premolar to the maxillary left first premolar four years ago, but she dislikes the current situation as the restorations present some wear, and the initial anatomy provided (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Initial extra-oral situation. (A) Face smiling and (B) close-up of the smile.

Figure 2.

Initial intra-oral situation. (A) Frontal, (B) right, and (C) left side views.

The patient was presented with a comprehensive treatment plan, including crown lengthening to improve the gingival architecture of the anterior teeth, followed by feldspathic porcelain veneers from the maxillary right first premolar to the left first premolar. However, the patient declined the crown lengthening procedure and requested only the ceramic veneers. The patient was informed that, due to the low smile line, avoiding the crown lengthening procedure was still an acceptable option. Additionally, the patient was informed about the option of having the resin composite veneers removed in a minimally invasive manner with an Er:YAG laser, instead of using traditional dental burs, and she accepted this option.

The patient was informed that a diagnostic wax-up would be completed, followed by an intra-oral mock-up to evaluate the proposed restorations. Once the diagnostic wax-up (Wax GEO Classic, Renfert, Hilzingen, Germany) and mock-up (Integrity, Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA) were performed, the patient was satisfied and pleased with the esthetic outcome and consented to proceed with treatment for feldspathic veneers from the maxillary right first premolar to the left first premolar.

At the next visit, isolation of the maxillary arch from the right first molar to the left first molar was achieved using a dental dam (Dental Dam, Nic Tone, Bucharest, Romania), stabilized with clamps (#00 Clamp, Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA). The existing resin composite veneers were removed with an Er:YAG laser, and veneer preparations were refined using a dedicated veneer preparation bur kit (Solution Laminate Veneer Preparation System, Brasseler, Savannah, GA, USA). A double retraction cord technique was employed using Ultrapak #000 (Ultradent, South Jordan, UT, USA) (Figure 3) for further isolation and visibility.

Figure 3.

Removal of composite veneers. (A) Placement of modified dental dam; (B) frontal, (C) right side, and (D) left side views; (E) cord packed prior impression.

Final tooth preparations were polished using polishing discs (Sof-Lex XT Disc, 3M, St. Paul, MN, USA) in a sequence of coarse, medium, and fine grits. A final digital impression (Aoralscan 3, Shinning 3D, Hangzhou, China) was then taken for the maxilla, mandible, and both arches in occlusion. The final veneer restorations were digitally designed (Dental-CAD 3.1, Exocad, Darmstadt, Germany) following the contours previously approved in the diagnostic mock-up.

Next, the ceramic laminate veneer restorations were milled from lithium disilicate (shade A1, Amber Mill, Hass Bio, Gangneung, South Korea). The restorations were tested to evaluate their margins, contour, and shade. The patient approved them as shown and asked to proceed with the final cementation process.

The final ceramic veneers were first treated with 5% hydrofluoric acid (IPS Ceramic Etching Gel, Ivoclar, Schaan, Liechtenstein) for 20 s, followed by cleaning in an ultrasonic bath with 96% isopropyl alcohol for 5 min. Silane (Monobond Plus, Ivoclar, Schaan, Liechtenstein) was then applied for 60 s. The teeth were sandblasted with water and 20 µm aluminum oxide particles, followed by the application of 37% phosphoric acid (Total Etch, Ivoclar, Schaan, Liechtenstein) for 20 s. The teeth were rinsed, dried, and primed before applying adhesive (Optibond FL, Kerr, Brea, CA, USA).

Finally, the veneers were cemented with light-cured luting resin cement (Choice 2, Bisco Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA) under rubber dam isolation, starting with the two central incisors, followed by the laterals, canines, and first premolars. The patient was satisfied with the contour and shade of the veneer restorations (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Final bonded ceramic veneers. (A) Patient smiling, (B) intra-oral view, and (C) close-up of the smile.

The patient was advised to brush her teeth three times a day and was instructed to attend follow-up visits every 6 months to evaluate the restorations and receive dental prophylaxis. Additionally, the patient was provided with an occlusal guard to protect the restorations at night. At the 3-year follow-up visit, the patient remained satisfied with the shade and shape of the laminate veneers (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Three-year follow-up. (A) Frontal, (B) left, and (C) right side intra-oral views.

A summary of the clinical procedures performed can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the clinical workflow performed.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review Outcomes

The literature offers several studies evaluating the effectiveness of using Er:YAG to remove bonded materials on teeth. The methodological quality of each study was assessed by one reviewer (F.A.). The findings from a brief literature review of articles detailing the outcomes are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Publications on clinical efficacy of using Er:YAG to remove bonded restorative materials.

The following aspects were analyzed for the articles on the removal of veneers using an Er:YAG laser: specimen randomization, control group, standardized specimens, manufacturer’s instructions, single operator, availability of outcome data, and overall assessment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Specimen randomization, control group, standardized specimens, manufacturer’s instructions, single operator, availability of outcome data, and overall assessment for the articles on removal of veneers using Er:YAG laser (references [11,12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27]).

3.2. Clinical Study Outcomes

The workflow implemented in this clinical study successfully met the patient’s esthetic demands. The removal of the veneers using the Er:YAG laser provided a more conservative approach and significantly expedited the process compared to traditional methods of restoration removal performed manually with a high-speed handpiece. The periodontal soft tissues surrounding the restorations remained undamaged during the removal process, and their health was preserved both during the procedure and after the cementation of the veneer restorations.

The patient was provided with an occlusal guard to protect the restorations at night. Additionally, they received oral hygiene instructions and were advised to undergo dental prophylaxis every six months. During these follow-up visits, the restorations were re-evaluated to ensure their continued success. The clinical workflow performed in this study is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Summary of the clinical study workflow.

4. Discussion

Although composite resin veneers offer esthetic benefits, their longevity is generally limited to around five years [8]. For this reason, the authors of this case chose to recommend replacement with porcelain veneers. Er:YAG lasers offer a precise method for selectively removing composite resin from enamel surfaces, especially in permanent teeth. This precision is due to water-mediated photomechanical interactions, which differ significantly from the more invasive action of dental burs that tend to remove healthy tooth structure along with the restoration. Enamel treated with Er:YAG lasers develops a rough, microretentive surface featuring exposed enamel rods, closely resembling the ideal pattern produced by acid etching for adhesive bonding. These laser-treated surfaces display features such as open tubules and roughened enamel, which promote strong adhesive bonds. Additionally, the lack of carbonization or thermal damage confirms the safety and appropriateness of the Er:YAG laser settings used (4 W power with water cooling). Lasers may reduce iatrogenic damage, but improper higher pulse rates (25 Hz) bring the risk of excessive heating and unintentional tissue ablation, which stresses the importance of operator expertise [25].

In addition to vaporizing the composite resin, a 2940 nm wavelength Er:YAG laser selectively vaporizes intertubular dentin (higher water content) while preserving peritubular dentin. This mechanism creates a microroughened surface ideal for adhesion without compromising pulp safety [25]. The comparison of ablation rates across composite resins (microfilled, hybrid, condensable) and dental hard tissues (primary/permanent enamel and dentin) revealed that the composite resin ablation rates were 5–10× higher than enamel, enabling preferential resin removal while preserving intact enamel. Hybrid composite resins showed the most favorable ablation rates compared to enamel and demonstrated optimal differential ablation compared to microfilled (prone to rough ablation) and condensable (fiberglass-reinforced) resins [26].

In this case report, the tooth preparation was limited to smoothing line angles and establishing an insertion path. This approach boosts the conservative protocol through diagnostic validation and guided preparation, controlled moisture conditions during the bonding procedures by using a rubber dam, and minimal thickness requirements for the felspathic material, aligning with enamel preservation and biomimetic goals [27].

The use of Er:YAG laser conditioning is an alternative to conventional acid etching for preparing tooth surfaces prior to Class V restorations, and pit and fissure sealants were investigated [28]. There were significant differences in microleakage between occlusal (enamel) and cervical (cementum/dentin) margins. In Class V restorations, the group using laser conditioning on cementum with composite restoration exhibited higher microleakage compared to groups treated with acid etching or combined methods. However, further research—with larger sample sizes and standardized protocols—is needed to validate these in vitro findings and to determine the clinical efficacy of laser etching in reducing microleakage.

A qualitative comparison of the effectiveness of Er:YAG lasers revealed that this technology performed better than the conventional technique for removing composite remnants but produced more enamel ablation [14]. A tungsten carbide bur and enamel ablation (two Er:YAG laser intervals) were used after bracket debonding from 12 extracted premolars (four premolars served as a control). The Er:YAG laser removed composite remnants faster, applied for 10 s, compared to the variable time with the tungsten carbide burs. The Er:YAG laser is a viable method for removing composite remnants after bracket debonding, performing better than mechanical removal. The amount of enamel ablation is a disadvantage, and further studies with lower energy intervals and pulse repetitions are recommended to find ideal specifications for Er:YAG laser application without affecting enamel.

The findings from a study on the use of Er:YAG lasers for debonding orthodontic brackets, focusing on their effectiveness, safety concerning enamel damage, and recommendations for future monitoring of enamel health revealed that the laser application facilitates removal of brackets, particularly ceramic ones, while significantly reducing the amount of adhesive residue left on the enamel surface [15]. The highlighted superior debonding efficiency of Er:YAG lasers for bracket debonding compared to traditional mechanical methods is encouraging, but it is essential to consider long-term enamel health. Regular follow-up appointments should include evaluations of enamel integrity and the presence of any residual adhesive that may contribute to caries risk.

The effectiveness and safety of Er:YAG lasers for the debonding of lithium disilicate crowns were investigated, with particular attention to whether laser power settings influenced the procedure when applied to crowns of varying thicknesses [16]. A laser power setting of 5 W was found to be optimal for debonding 1 mm thick lithium disilicate crowns, demonstrating both safety and efficacy for this specific thickness. In contrast, higher power settings of 5.6 W and 5.9 W, tested on thicker crowns (1.5 mm and mixed thickness), resulted in reduced debonding times but raised concerns regarding dental pulp safety. Although increased laser energy may improve efficiency, it also poses risks, particularly for thinner crowns. Therefore, clinicians should prioritize minimizing heat transmission to protect the underlying vital tissues. By following the recommended power settings—5 W for 1.0 mm crowns and cautiously increasing output for thicker ones—dentists can enhance the debonding process while reducing potential harm to pulp vitality.

One of the most significant aspects is the laser tip’s distance from the surface. It has been found marked differences in debonding times between non-contact mode (NCM) and contact mode (CM) when using Er:YAG lasers—12.6 s for NCM compared to 96.3 s for CM [17]. This notable reduction in debonding time underscores the potential of NCM to improve procedural efficiency in clinical practice by decreasing chair time and allowing for faster patient turnover. While the enhanced efficiency of NCM is evident, it is essential to consider safety aspects, particularly the rise in dental pulp temperature during debonding. This study reported an average temperature increase of 4.2 °C with NCM and 2.9 °C with CM. Although both values remained below the critical threshold of 5.25 °C for pulp survival, the greater temperature rise associated with NCM suggests a heightened risk of thermal injury if not closely monitored. Therefore, clinical decision-making must balance the efficiency benefits of NCM with the potential for pulp tissue damage. The evaluation of various laser settings—such as 360 mJ at 15 Hz and 400 mJ at 10 Hz—revealed a notable impact on both debonding duration and temperature changes in the pulp, emphasizing the importance of selecting and optimizing parameters to ensure both efficacy and safety [17].

Considering these findings, several strategies have been proposed for improving the clinical application of Er:YAG lasers in crown debonding. Primarily, practitioners are encouraged to utilize NCM for its time-saving advantages if pulp temperature is carefully monitored throughout the procedure. Furthermore, ongoing research is recommended to investigate a wider range of laser settings, with the aim of identifying combinations that effectively balance performance and thermal safety. Lastly, emphasis should be placed on continued education and hands-on training in laser technology, ensuring that dental professionals are well prepared to use these tools with competence and confidence [17].

The Er:YAG laser has become an important tool in modern dental practice, especially for the removal of all-ceramic restorations [18]. To ensure optimal outcomes for both the tooth structure and ceramic materials, clinicians must follow specific preparation protocols before initiating the debonding process. These include thorough tooth surface preparation, where enamel and dentin are appropriately reduced to establish a suitable bonding substrate for future restorations. Ceramic material selection is equally crucial; materials such as leucite or lithium disilicate should be properly bonded using a dual-cure resin cement to ensure durable adhesion. In addition, clinicians must set the laser parameters carefully, typically using a 2940 nm wavelength, around 3 W of power, a pulse duration, and a frequency of approximately 10 Hz (e.g., 300 mJ), tailored to the specific clinical context. An air–water cooling mechanism should also be employed to minimize thermal impact on both dental and ceramic structures, thereby preserving the integrity of the restoration and surrounding tissues.

During the debonding procedure, several considerations should be considered to maximize the benefits of the Er:YAG laser [18]. In terms of effective debonding, the laser successfully removes resin-luted ceramic restorations without damaging either the tooth surface or the restoration itself, preserving the possibility for future rebonding. The laser functions through controlled mechanisms, primarily thermal and photoablation, which maintain resin and dentin temperatures within safe physiological limits, thereby minimizing the risk of heat-induced damage. Regarding bond strength, while the use of the Er:YAG laser may result in a slight reduction in shear bond strength compared to untreated controls, it does not significantly compromise the rebonding strength of the restorations. These findings support Er:YAG laser clinical applicability for procedures requiring restoration, replacement, or reattachment [23].

The influence of pulse duration and cooling ratios on the debonding process and their thermal impact on the dental pulp was previously evaluated, revealing that shorter pulse durations of 50 μs and 100 μs significantly decreased debonding times compared to the longer 300 μs setting [24]. This highlights the clinical efficiency of shorter pulse durations in achieving faster porcelain laminate veneer removal, making them preferable in practice. While the water-to-air (W/A) cooling ratio had minimal impact on debonding time and pulp temperature at shorter pulse durations, it became more relevant with extended durations. Notably, the highest rise in pulp temperature—3.4 °C—was observed with the 300 μs setting at a 1:1 W/A ratio. In contrast, the 50 μs and 100 μs time maintained pulp temperatures below the critical threshold of 5.5 °C, thereby improving procedural safety. Based on these findings, the use of 50 μs or 100 μs pulse durations is recommended for the safe and efficient debonding of porcelain laminate veneers, as they reduce procedure time while keeping dental pulp temperature within safe physiological limits, minimizing the risk to tooth structures [24].

The efficiency of the debonding process is greatly affected by the thickness of ceramic veneers, with thinner veneers (0.5 mm) enabling better transmission of laser energy. As a result, they can be removed more quickly and with less residual adhesive left on their surface compared to thicker veneers (1.0 mm) [25]. Veneers measuring 1.0 mm not only required more time to debond but also led to a greater increase in temperature. In contrast, 0.5 mm veneers were successfully removed in under six seconds with minimal heat generation. These results emphasize the need to consider veneer thickness when adjusting laser power settings to ensure effective and safe clinical outcomes [35]. The authors of a study on the use of an Er:YAG laser to debond porcelain veneers without damaging the underlying tooth and retaining the veneer examined the transfer of energy through veneers with different thicknesses. They found that Er:YAG laser irradiation efficiently debonds porcelain veneers while preserving tooth structure. Maintaining veneer integrity throughout this process depends on the porcelain’s flexural strength. Using FTIR spectroscopy and visual inspection, testing the absorption characteristics and ablation threshold of the veneer cement was a key component of the methodology. This showed that while the bonding cement had a broad H2O/OH absorption band, the veneer materials showed no water absorption bands. The findings also showed that while lithium disilicate veneers transmitted approximately 26.5–43.7% at comparable thicknesses, leucite ceramic veneers transmitted about 11.5–21% of the laser energy. Using the Er:YAG laser in an average period of 113 s, leucite veneers were entirely removed; generally, these results imply that veneer flexural strength, rather than water uptake, is the main determinant of veneer fracture during laser debonding [21].

A study evaluating the debonding strength of laminate veneers after Er:YAG laser application on each veneer for 9 s using a scanning method reported significantly higher shear bond strengths (27.28 ± 2.24 MPa) in the control group compared to the laser-irradiated group (3.44 ± 0.69 MPa). This showed that laser energy can degrade the adhesive resin and substantially reduce the shear bond strength of laminate veneers. Er:YAG laser application thereby efficiently reduces the shear bond strength of laminate veneers, therefore enabling removal [21].

The use of Er:YAG lasers for veneer removal has been extensively studied, with particular focus on key elements such as debonding efficiency, tooth structure preservation, and clinical relevance [22]. One of the most critical factors influencing successful laser-assisted debonding is irradiation time. While the total time required for veneer removal typically stays under four minutes, it is essential to differentiate between actual working time and irradiation time, particularly when operating with pulsed laser systems. Variables like pulse duration and the time taken to reach peak power can have a notable impact on the procedure’s effectiveness. However, further investigation is needed to fully understand their precise influence on the debonding process [22].

Significant differences have been identified in the energy transmission properties of various crown materials, which directly impact the effectiveness of laser-assisted debonding procedures. E.max CAD crowns demonstrated superior laser energy transmission, enabling a more efficient debonding process [23]. In contrast, ZirCAD crowns were found to transmit approximately 80% less laser energy, resulting in a more time-consuming and technically challenging removal. Due to their thicker structure, ZirCAD crowns require higher laser energy settings to adequately reach and degrade the bonding cement, especially in hard-to-access areas such as contact points. This marked contrast in energy transmission capabilities underscores the critical importance of careful material selection in clinical scenarios involving laser debonding [23].

Erbium lasers have demonstrated a high success rate exceeding 95% for the intact removal of ceramic prostheses, markedly outperforming conventional rotary instruments [24]. This laser-assisted technique offers the advantage of preserving underlying structures, with no significant surface or chemical alterations detected on natural teeth or implant abutments. The effectiveness of erbium lasers is evident in the average removal times for various ceramic restorations: veneers take around 2.25 min, crowns approximately 6.89 min, and fixed partial dentures about 25 min per abutment. Although high-speed burs can remove composites more quickly (63.1 s) than lasers (121 s at 20 Hz), they tend to affect a larger area, whereas lasers provide a more conservative approach (0.800 mm vs. 0.372 mm of tooth structure at 20 Hz, respectively) [25]. Additionally, lithium disilicate crowns are typically easier and quicker to remove than zirconia crowns, which require longer treatment times. This procedural efficiency enhances patient comfort and contributes to a more streamlined, time-saving clinical workflow [25].

Aksakalli et al. conducted a comparison between two widely used surface treatment techniques—Er:YAG laser etching and hydrofluoric acid (HFA) etching—evaluating their effectiveness in achieving bond strength and their safety with respect to potential damage to porcelain surfaces and surrounding oral tissues [26]. HFA etching demonstrated the highest shear bond strength, averaging 10.8 ± 3.8 MPa, making it the most effective option for bonding orthodontic brackets to porcelain surfaces. In comparison, Er:YAG laser etching produced bond strengths that, while lower, remained within clinically acceptable limits for orthodontic applications. Considering the critical role of reliable bonding in orthodontic treatment, clinicians are encouraged to weigh both bond strength and safety when selecting an etching method. This study supports a strong recommendation for the clinical use of Er:YAG laser etching, particularly when safety is a primary concern [26].

Juntavee et al. investigated the effectiveness of various surface treatments, focusing on acid etching and Er:YAG laser treatment, in terms of their impact on the shear bond strength of ceramic brackets bonded to materials such as porcelain fused to metal, IPS Empress CAD, and IPS e.max CAD [27]. The findings revealed that Er:YAG laser treatment achieved bond strength comparable to that of a 15 s acid etching protocol, establishing it as a viable alternative. Importantly, Er:YAG laser treatment also reduces the risk of damaging the ceramic surface during the debonding process, which presents a notable clinical advantage [27].

Ismatullaev et al. compared the efficacy of laser etching and acid etching on bond strength, with particular attention to enamel and dentin surfaces, offering recommendations for clinical application based on current evidence [28]. The morphological changes caused by each technique significantly influence bonding performance. Laser etching generates a unique surface characterized by demineralization and the opening of dentinal tubules without forming a smear layer, thereby enhancing adhesive penetration into exposed collagen fibrils. Conversely, acid etching typically results in a generalized roughening of the enamel surface, which may not consistently support optimal bonding. These distinct surface alterations affect how well adhesive systems perform when paired with either method, emphasizing the importance of choosing an appropriate etching technique for clinical success [28].

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are proposed for clinical practice [29,36,37,38,39]:

- o

- Laser etching, specifically with the Er:YAG scanning handpiece, may be an effective alternative to traditional acid etching for both enamel and dentin. This approach yields a more uniform surface morphology, which may enhance bond quality.

- o

- Clinicians should adjust laser parameters, such as 120 mJ, 10 Hz, and 1.2 W, to improve bond strength. The application of double irradiation to dentin may increase the adhesive surface area and improve bond strength values.

- o

- It is essential to assess the variability in bond strength outcomes associated with various etching methods. Clinicians must evaluate material-specific and procedural factors to obtain reliable results.

- o

- Further clinical studies are necessary to enhance the understanding of the comparative effects of laser etching and acid etching across various treatment contexts.

- o

- Observe alterations in dentin tubules: The impact of etching on the diameter of dentin tubules warrants consideration, as reduced diameters may hinder resin infiltration and influence bonding effectiveness. Understanding these effects facilitates more informed decisions in the selection of etching techniques.

Emphasizing the need for clinician training and knowledge with the laser system, Oztoprak et al. provided evidence-based advice for the safe and efficient use of Er:YAG lasers in the debonding of porcelain laminate veneers [29]. Efficient veneer removal depends on precise knowledge of certain laser parameters, including power and wavelength, and expertise in scanning methods. To preserve best practices in laser-assisted debonding [29], clinicians are urged to remain current with the literature and engage in hands-on training. Routine assessment of bond strength is also recommended to gauge the efficacy of the treatment, hence guiding practitioners to change their strategy depending on clinical results and patient input. The safety and efficiency of Er:YAG laser use in patient care is supported by this constant review [29].

Considering that this review combines in vitro, ex vivo, and clinical studies, care should be taken not to extrapolate the findings to similar clinical scenarios, especially considering the methodological variability involved in the studies. Further research should validate these findings using similar materials and assess long-term effects on bonding; further research should focus on parameter optimization, i.e., refining pulse durations (e.g., ultra-short pulses) to reduce thermal stress; the use of adjunctive technologies, combining air abrasion or enzymatic solutions to enhance adhesive breakdown; and the development of compact, cost-effective Er:YAG handpieces for chairside debonding procedures.

5. Conclusions

The Er:YAG laser creates clean, microretentive surfaces on dentin and enamel, making it a valuable tool for conservative dental treatments. With improvements in laser settings and user training, its precision and range of use are likely to grow. This technology marks a step forward in restorative dentistry by offering accuracy and tooth preservation that traditional methods cannot match. Although some material-related challenges remain, ongoing progress in laser technology and surface treatments is expected to increase its usefulness, especially for minimally invasive procedures. Er:YAG laser-assisted veneer removal is a safe and reliable option for replacing old composite veneers with feldspathic porcelain ones, supporting modern, tooth-conserving approaches to restorations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.V.-T. and F.A.; methodology, C.C.; software, S.R.-R.; validation, N.G.F., C.A.J. and M.P.-B.; formal analysis, F.A.; investigation, C.C. and M.P.-B.; resources, S.R.-R.; data curation, N.G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.; writing—review and editing, C.A.J.; visualization, J.V.-T.; supervision, C.A.J. and M.P.-B.; project administration, C.C. and M.P.-B.; funding acquisition, S.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to not using a novel dental material.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Araujo, E.; Perdigão, J. Anterior Veneer Restorations—An Evidence-based Minimal-Intervention Perspective. J. Adhes. Dent. 2021, 23, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossato, D.M.; Bandeca, M.C.; Saade, E.G.; Lizarelli, R.F.; Bagnato, V.S.; Saad, J.R. Influence of Er:YAG laser on surface treatment of aged composite resin to repair restoration. Laser Phys. 2009, 19, 2144–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratieri, L.N.; Monteiro Júnior, J.; de Andrada, M.A.; Aracari, G.M. Composite resin veneers: A new technique. Quintessence Int. 1992, 23, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mangani, F.; Cerutti, A.; Putignano, A.; Bollero, R.; Madini, L. Clinical approach to anterior adhesive restorations using resin composite veneers. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2007, 2, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Edelhoff, D.; Prandtner, O.; Saeidi Pour, R.; Liebermann, A.; Stimmelmayr, M.; Güth, J.F. Anterior restorations: The performance of ceramic veneers. Quintessence Int. 2018, 49, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malchiodi, L.; Zotti, F.; Moro, T.; De Santis, D.; Albanese, M. Clinical and Esthetical Evaluation of 79 Lithium Disilicate Multilayered Anterior Veneers with a Medium Follow-Up of 3 Years. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jurado, C.; Watanabe, H.; Tinoco, J.V.; Valenzuela, H.U.; Perez, G.G.; Tsujimoto, A. A conservative approach to ceramic veneers: A case report. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, A.; Jurado, C.A.; Villalobos-Tinoco, J.; Fischer, N.G.; Alresayes, S.; Sanchez-Hernandez, R.A.; Watanabe, H.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Minimally invasive multidisciplinary restorative approach to the esthetic zone including a single-discolored tooth. Oper Dent. 2021, 46, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, I.R.; Özcan, M. Reparative Dentistry: Possibilities and Limitations. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2018, 5, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guess, P.C.; Schultheis, S.; Wolkewitz, M.; Zhang, Y.; Strub, J.R. Influence of preparation design and ceramic thicknesses on fracture resistance and failure modes of premolar partial coverage restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 110, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- El-Damanhoury, H.M.; Elsahn, N.A.; Sheela, S.; Gaintantzopoulou, M.D. Adhesive luting to hybrid ceramic and resin composite CAD/CAM Blocks: Er:YAG Laser versus chemical etching and micro-abrasion pretreatment. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, F.D.F.; Briso, A.L.F.; Ramos, F.d.S.E.S.; Esteves, L.M.B.; Omoto, É.M.; Sundfeld, R.H.; Fagundes, T.C. Use of auxiliary devices during retreatment of direct resin composite veneers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gozneli, R.; Sendurur, T. Er:YAG laser lithium disilicate crown removal: Removal time and pulpal temperature change. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, E.; Shayegan, A. Assessment of microleakage of class V restored by resin composite and resin-modified glass ionomer and pit and fissure resin-based sealants following Er:YAG laser conditioning and acid etching: In vitro study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2018, 10, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, H.C.; Vedovello Filho, M.; Vedovello, S.A.; Young, A.A.; Ramirez-Yanez, G.O. ER:YAG laser for composite removal after bracket debonding: A qualitative SEM analysis. Int. J. Orthod. 2009, 20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dostalova, T.; Jelinkova, H.; Remes, M.; Šulc, J.; Němec, M. The use of the Er:YAG laser for bracket debonding and its effect on enamel damage. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozneli, R.; Sendurur, T.; Silahtar, E. A preliminary study in Er:YAG laser debonding of lithium disilicate crowns: Laser power setting vs crown thickness. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALBalkhi, M.; Swed, E.; Hamadah, O. Efficiency of Er:YAG laser in debonding of porcelain laminate veneers by contact and non-contact laser application modes (in vitro study). J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagoz-Yildirak, M.; Gozneli, R. Evaluation of rebonding strengths of leucite and lithium disilicate veneers debonded with an Er:YAG laser. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Damanhoury, H.M.; Salman, B.; Kheder, W.; Benzina, D. Er:YAG laser debonding of lithium disilicate laminate veneers: Effect of laser power settings and veneer thickness on the debonding time and pulpal temperature. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 13, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morford, C.K.; Buu, N.C.; Rechmann, B.M.; Finzen, F.C.; Sharma, A.B.; Rechmann, P. Er:YAG laser debonding of porcelain veneers. Lasers Surg. Med. 2011, 43, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseri, U.; Oztoprak, M.O.; Ozkurt, Z.; Kazazoglu, E.; Arun, T. Effect of Er:YAG laser on debonding strength of laminate veneers. Eur. J. Dent. 2014, 8, 058–062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Rocca, J.P.; Fornaini, C.; Zhen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Merigo, E. Erbium-Doped, Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet Laser Debonding of Porcelain Laminate Veneers: An: Ex vivo: Study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechmann, P.; Buu, N.C.; Rechmann, B.M.; Finzen, F.C. Laser all-ceramic crown removal—A laboratory proof-of-principle study—Phase 2 crown debonding time. Lasers Surg. Med. 2014, 46, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, J.G.; Grzech-Lesniak, K.; Bencharit, S. Evaluation of the effectiveness and practicality of erbium lasers for ceramic restoration removal: A retrospective clinical analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksakalli, S.; Ileri, Z.; Yavuz, T.; Malkoc, M.A.; Ozturk, N. Porcelain laminate veneer conditioning for orthodontic bonding: SEM-EDX analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntavee, N.; Juntavee, A.; Wongnara, K.; Klomklorm, P.; Khechonnan, R. Shear bond strength of ceramic bracket bonded to different surface-treated ceramic materials. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismatullaev, A.; Taşın, S.; Usumez, A. Evaluation of bond strength of resin cement to Er:YAG laser-etched enamel and dentin after cementation of ceramic discs. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oztoprak, M.O.; Tozlu, M.; Iseri, U.; Ulkur, F.; Arun, T. Effects of different application durations of scanning laser method on debonding strength of laminate veneers. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, S.; Sulaiman, T.A.; Deeb, J.G.; Abdulmajeed, A.; Abdulmajeed, A.; Närhi, T. Er:YAG laser debonding of zirconia and lithium disilicate restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 253.e1–253.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Wu, X.; Li, Q.; Zhao, J.; Guo, C. Effects of Er:YAG laser debonding on changes in the properties of dental zirconia. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- ISO (2024) ISO 6872:2024. Dentistry: Ceramic Materials. Dental Ceramics—Performance Criteria for Safety and Performance Based Pathway—Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. FDA, 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/182281/download (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Jiang, L.; Li, X.Y.; Lu, Z.C.; Yang, S.; Chen, R.; Yu, H. Er:YAG laser settings for debonding zirconia restorations: An in vitro study. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 151, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, S.; Sulaiman, T.; Deeb, J.G.; Abdulmajeed, A.; Abdulmajeed, A.; Närhi, T. Effect of Er:YAG laser on debonding zirconia and lithium disilicate crowns bonded with 2- and 1-bottle adhesive resin cements. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2024, 36, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babarasul, D.O.; Faraj, B.M.; Kareem, F.A. Scanning electron microscope image analysis of bonding surfaces following removal of composite resin restoration using Er:YAG laser: In vitro study. Scanning 2021, 2021, 2396392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakrzewski, W.; Dobrzynski, M.; Kuropka, P.; Matys, J.; Malecka, M.; Kiryk, J.; Rybak, Z.; Dominiak, M.; Grzech- Lesniak, K.; Wiglusz, K.; et al. Removal of composite restoration from the root surface in the cervical region using Er:YAG laser and drill—In vitro study. Materials 2020, 13, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarelli, R.D.; Moriyama, L.T.; Bagnato, V.S. Ablation of composite resins using Er:YAG laser—Comparison with enamel and dentin. Lasers Surg. Med. Off. J. Am. Soc. Laser Med. Surg. 2003, 33, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, B.K. Effects of Er, Cr: YSGG Laser Application in De-Bonding of Different Ceramic Veneer Materials (In Vitro Study). Coatings 2023, 13, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBalkhi, M.; Hamadah, O. Influence of pulse duration and water/air cooling ratio on the efficiency of Er:YAG 2940 nm laser in debonding of porcelain laminate veneers: An in vitro study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).