White Shark Optimization for Solving Workshop Layout Optimization Problem

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. White Shark Optimizer

2.2. Workshop Layout

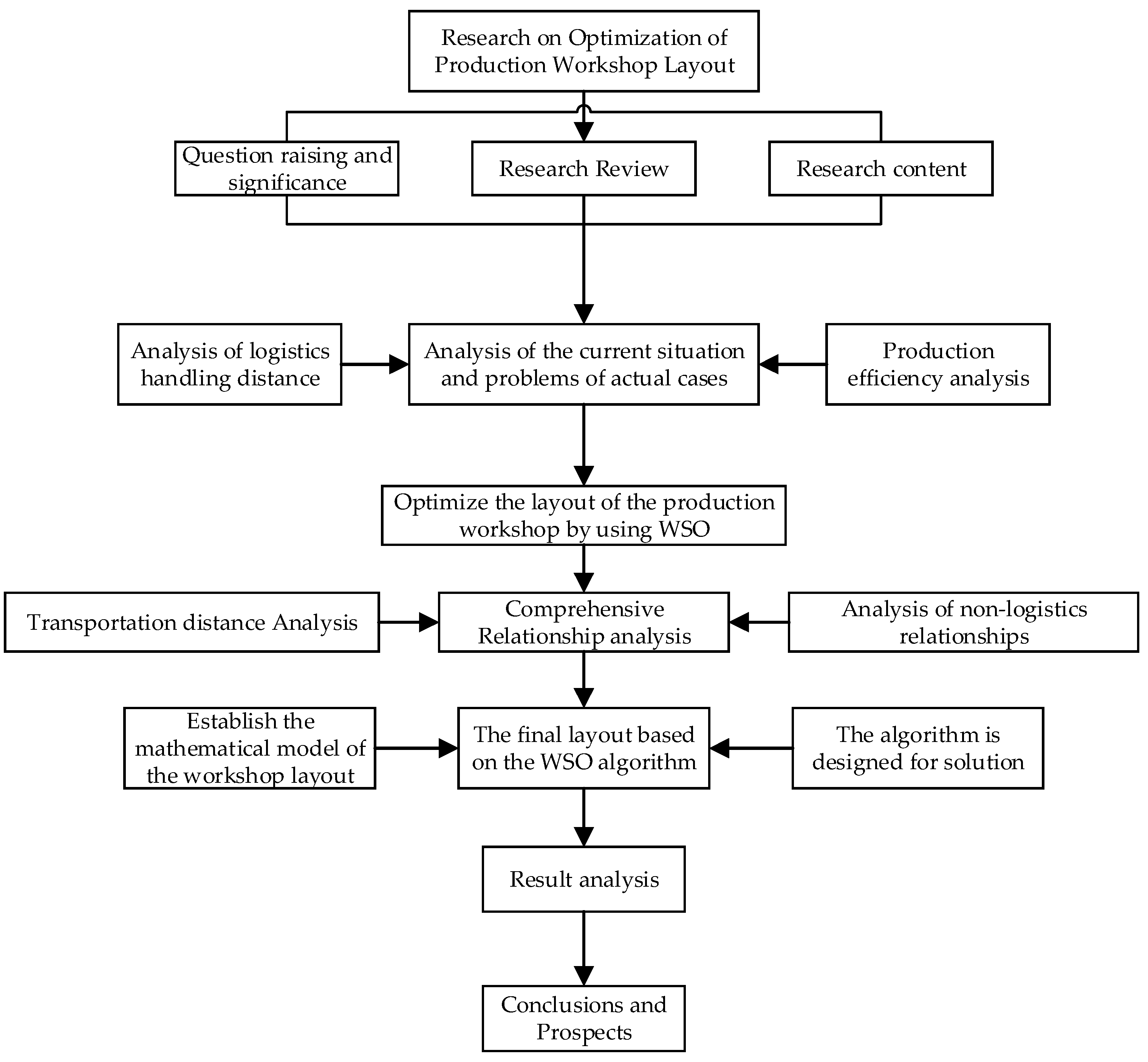

3. Methodology

3.1. Building Monomer Combination Model

- (1)

- Coordinate system setting assumption. Take the point at the lower left corner of the workshop as the origin of the rectangular coordinate system. The positive half of the –axis represents the long side direction of the entire workshop area, and the positive half of the –axis serves as the wide side direction of the workshop. This assumption, through the standard Cartesian coordinate system, avoids complex coordinate transformations and is applicable to rectangular or nearly rectangular workshops.

- (2)

- Floor plan assumption. All work units are on the same plane with no height differences, which conforms to the working scenarios of most enterprises. This assumption cannot optimize the logistics transportation in the three–dimensional direction.

- (3)

- Hypothesis of the shape of the working unit. Simplify the shape of each working unit to a rectangle, and stipulate that each rectangular edge is parallel to the X–axis and Y–axis. This assumption does not take into account the shapes of working units such as circles, which may lead to the waste of space.

- (4)

- Hypothesis of the entrance and exit of the work unit. The entry and exit points of each working unit are the center points of the rectangle. (,) represents the coordinates of the center point of working unit i, and (,) represents the coordinates of the center point of working unit j. This assumption takes into account the transportation distances between each workshop and may deviate from the actual transportation distances.

3.2. Objective Function

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

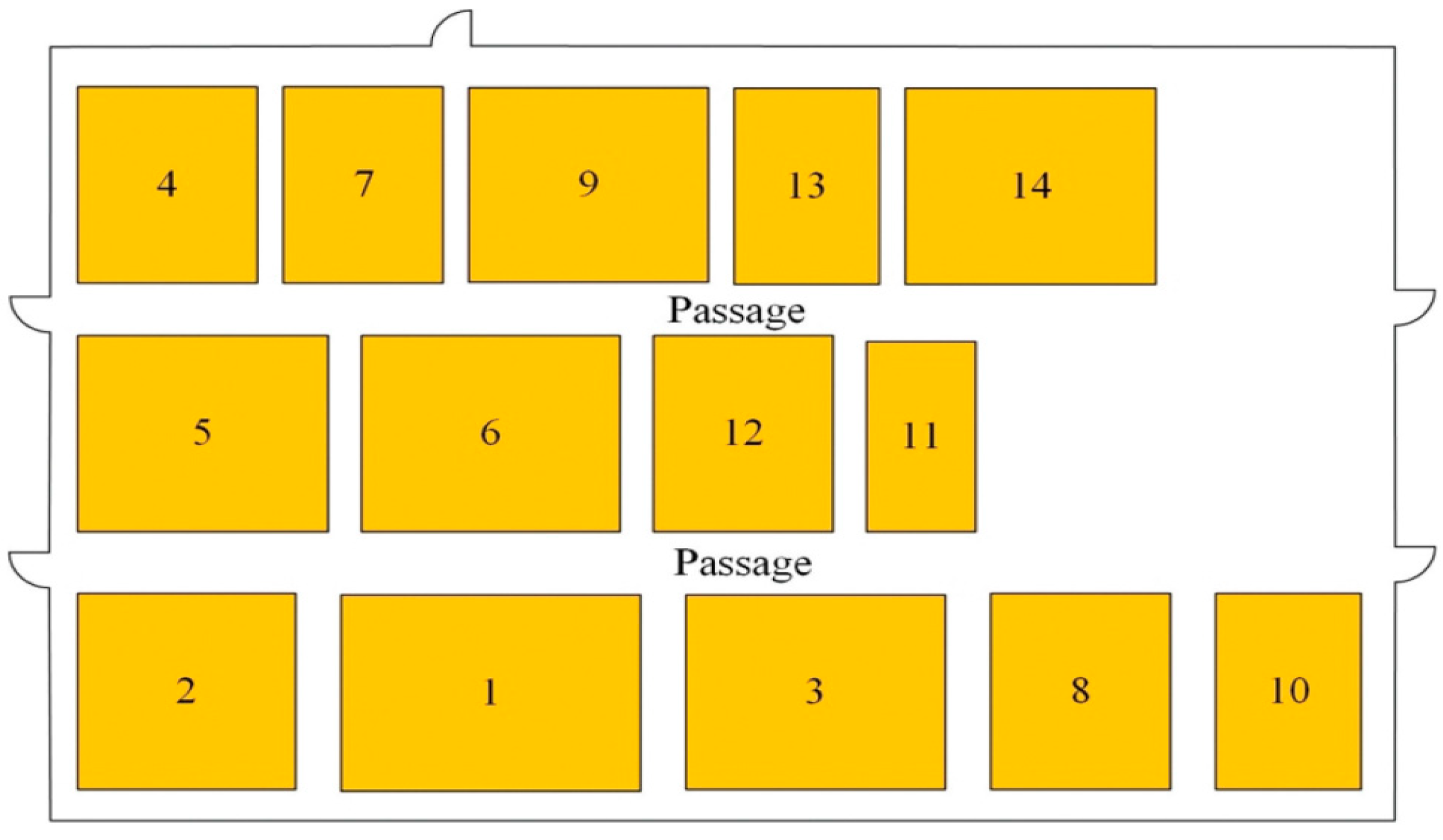

4.1. Case Study

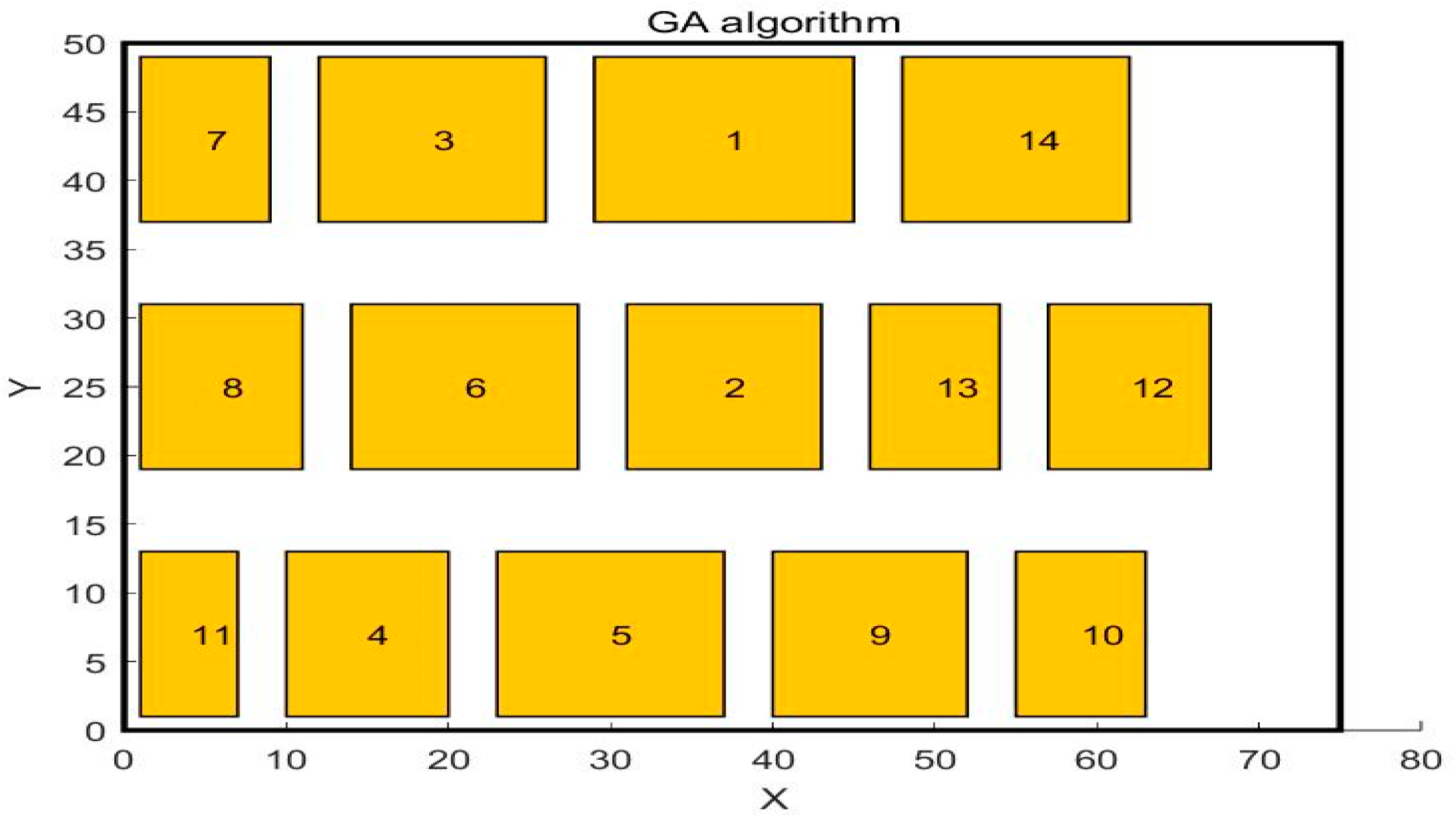

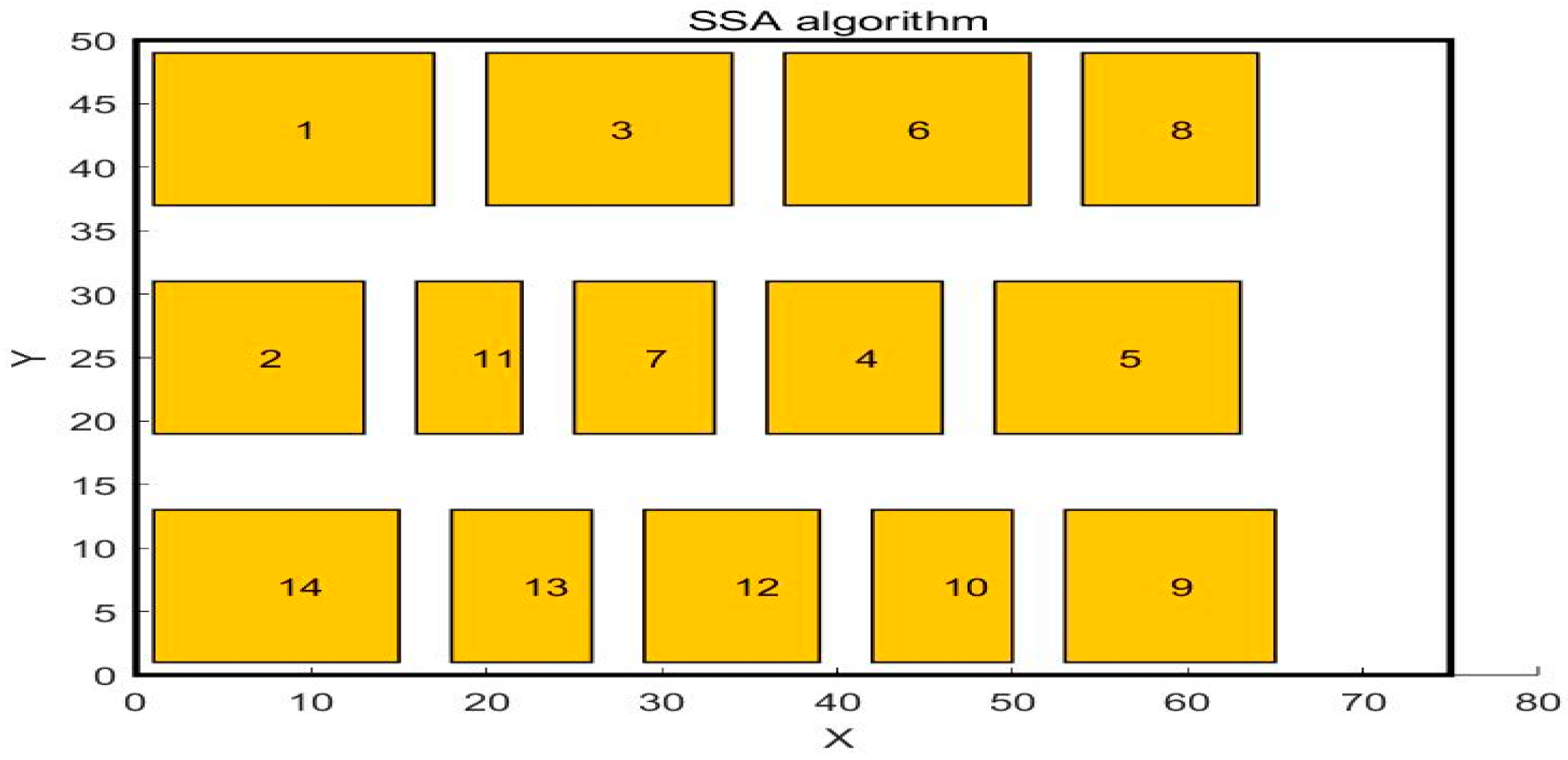

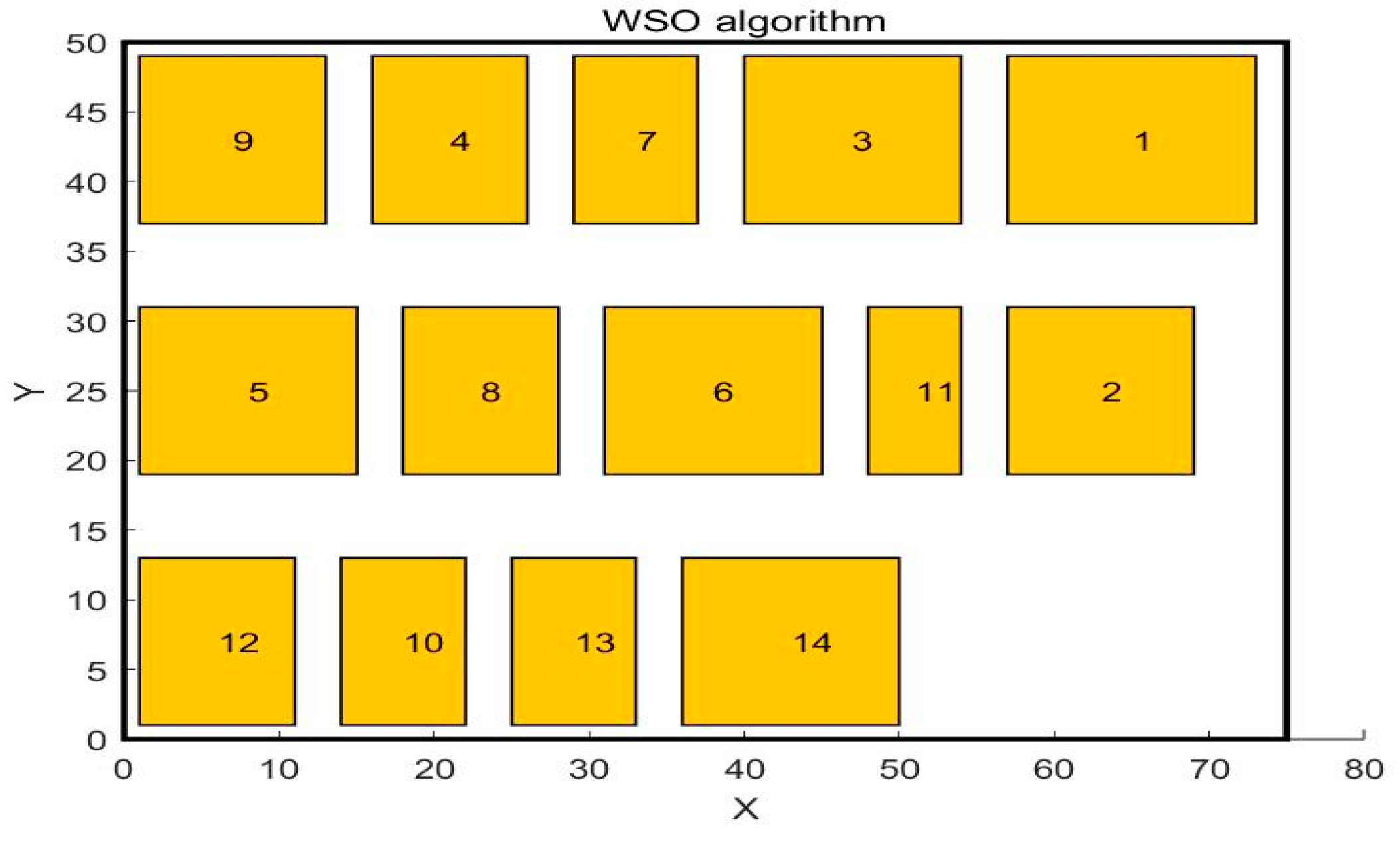

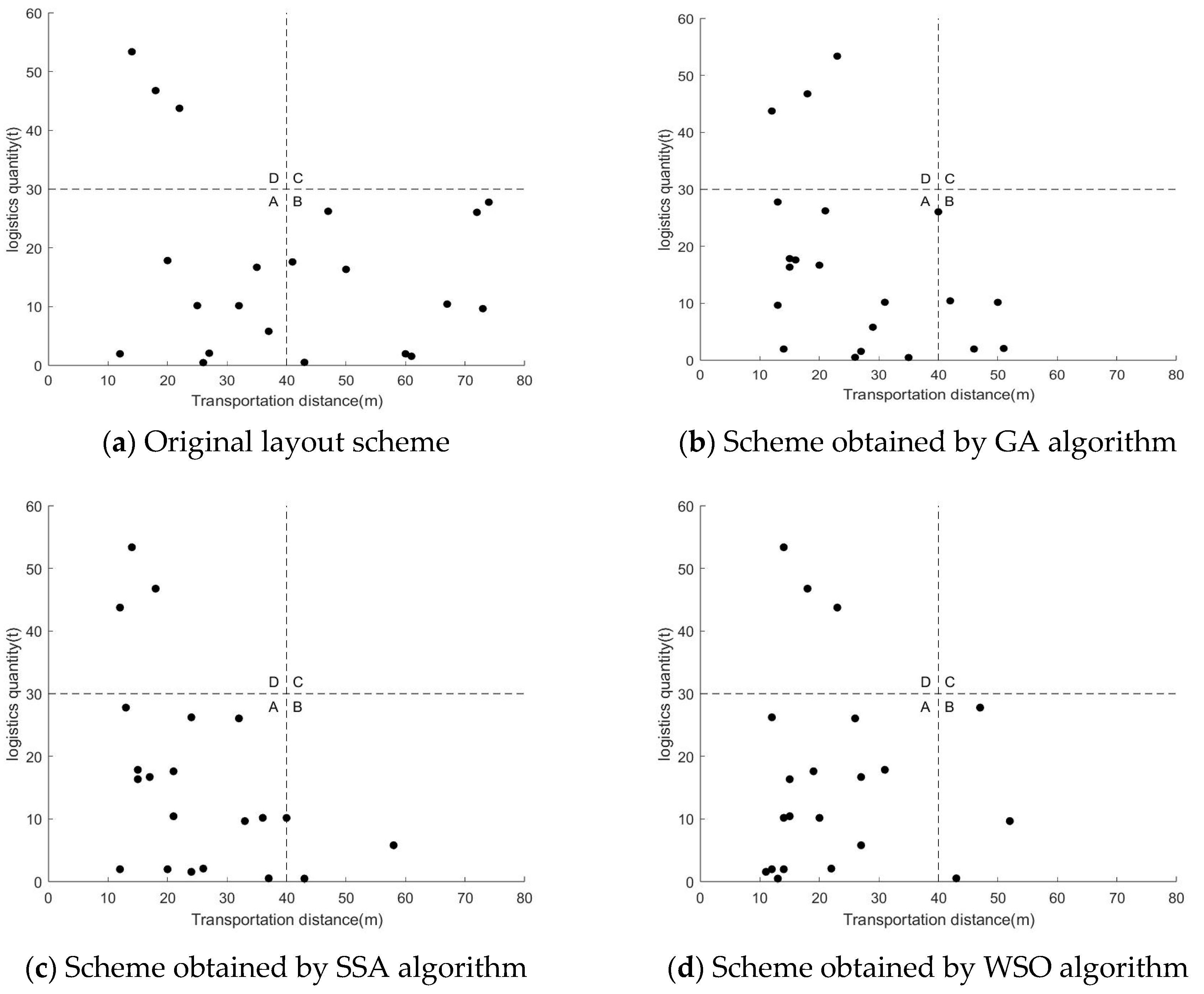

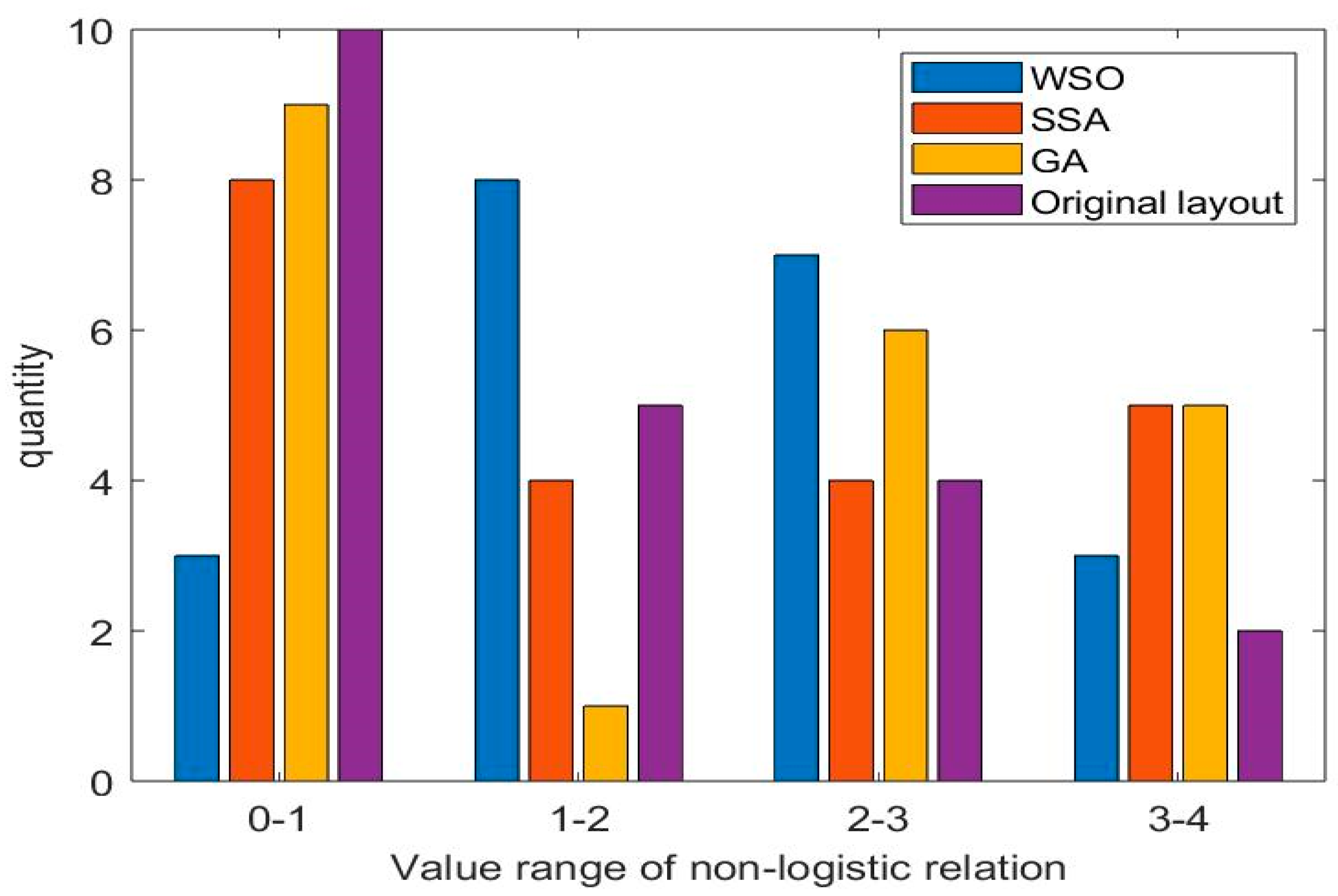

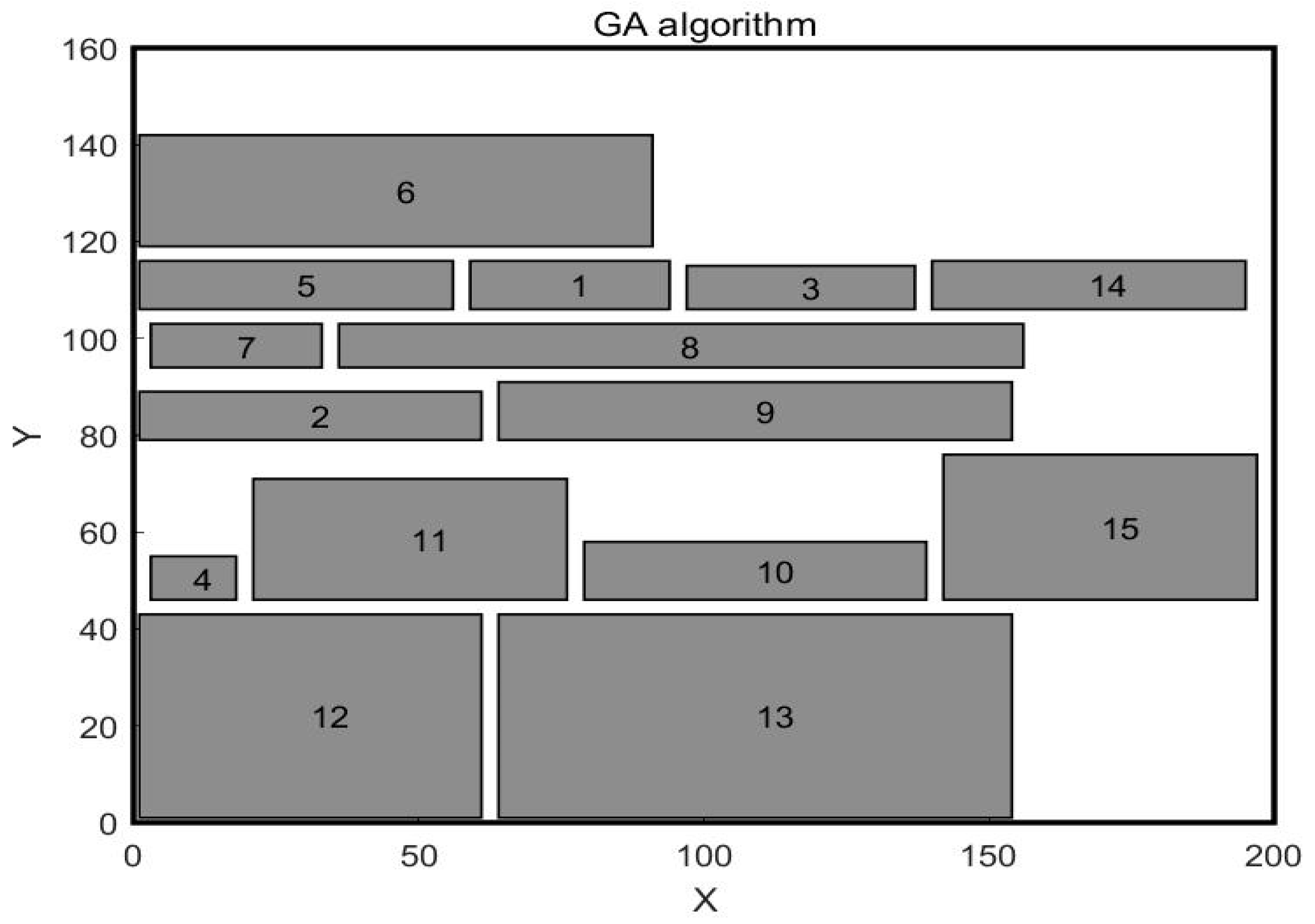

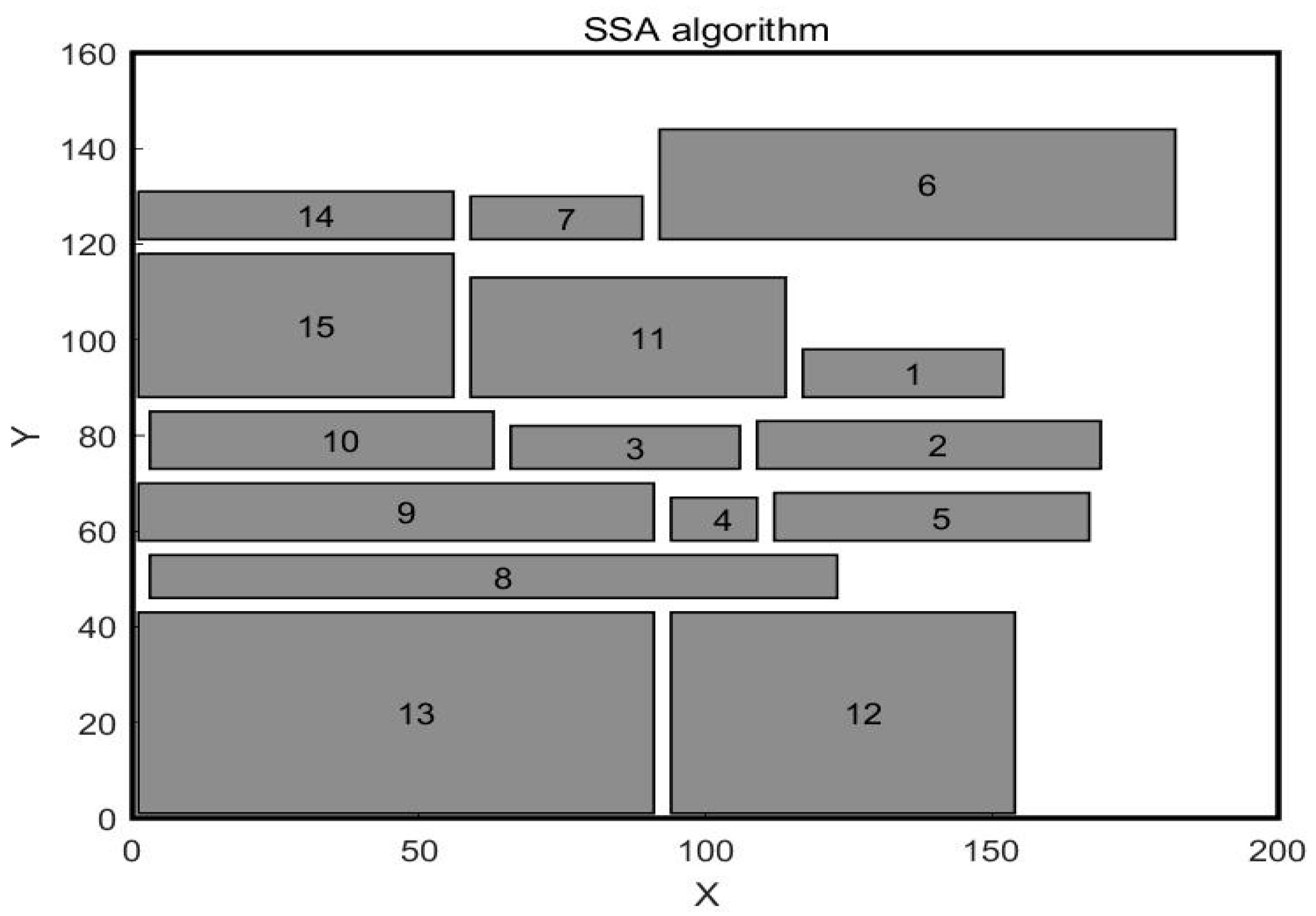

4.2. Analysis and Comparison

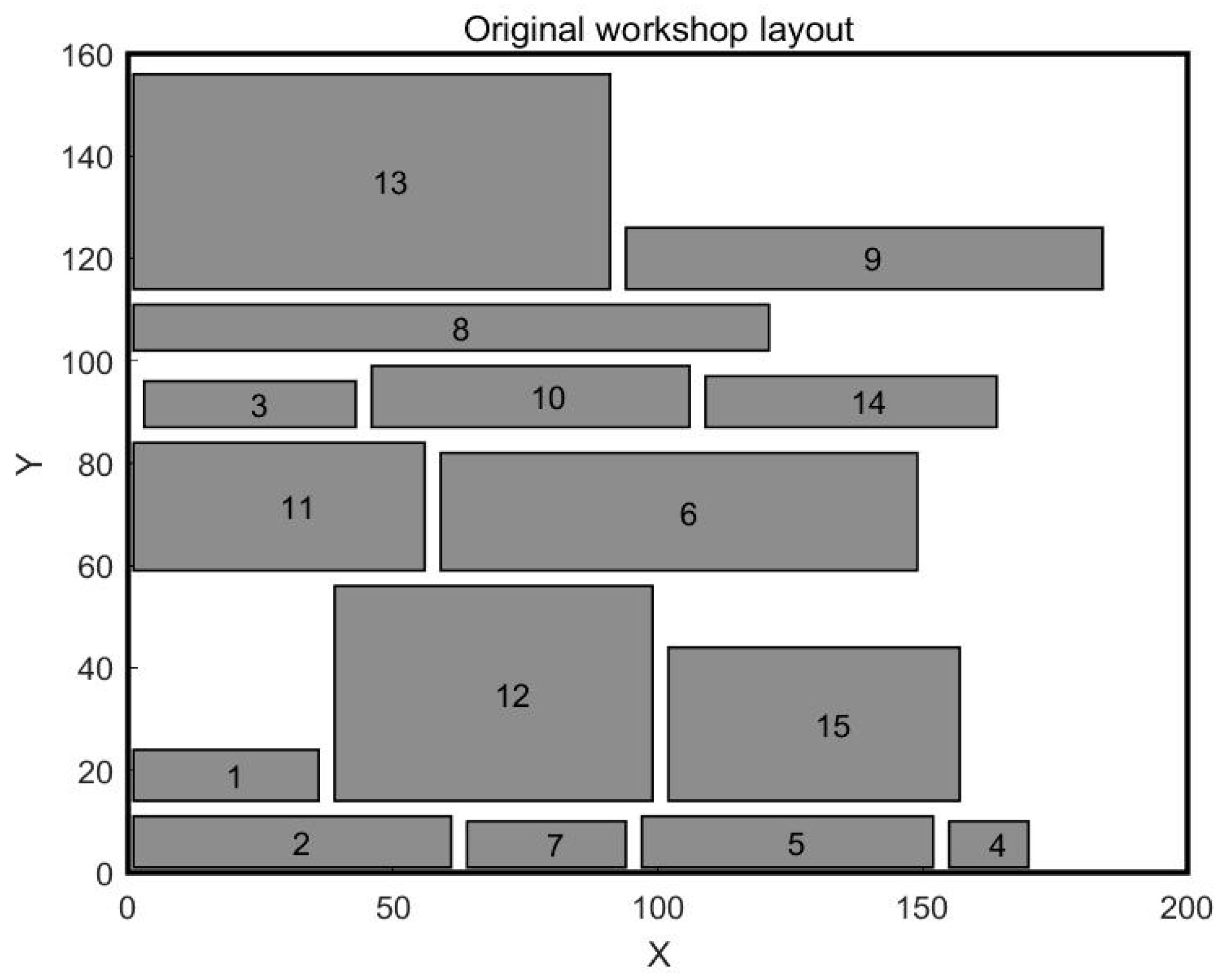

4.3. Case Development

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bag, S.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, S. Industry 4.0 adoption and 10R advance manufacturing capabilities for sustainable development. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 231, 107844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.G.; Winroth, M.P.; Ribeiro da Silva, E.H.D. Sustainable manufacturing in Industry 4.0: An emerging research agenda. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1462–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, B.; Zang, J.; Meng, L. Toward new–generation intelligent manufacturing. Engineering 2018, 4, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifai, A.P.; Windras Mara, S.T.; Ridho, H.; Norcahyo, R. The double row layout problem with safety consideration: A two–stage variable neighborhood search approach. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2022, 39, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khariwal, S.; Kumar, P.; Bhandari, M. Layout improvement of railway workshop using systematic layout planning (SLP)–A case study. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 4065–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini–Nasab, H.; Fereidouni, S.; Fatemi Ghomi, S.M.T.; Fakhrzad, M.B. Classification of facility layout problems: A review study. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms. Sci. Am. 1992, 267, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R. Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous space. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the 1995 IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolis, N.; Rosenbluth, A.; Rosenbluth, M.; Teller, A.; Teller, E. Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953, 21, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Maniezzo, V. Ant system: Optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Trans SMC–Part B 1996, 26, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braik, M.; Hammouri, A.; Atwan, J.; Al–Betar, M.A.; Awadallah, M.A. White Shark Optimizer: A novel bio–inspired meta–heuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Knowl.–Based Syst. 2022, 243, 108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.L.; Chung, S.H.; Chan, H.K.; Cui, L. An integrated model for berth and yard planning in container terminals with multi–continuous berth layout. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamer, S.; Barlas, B.; Gunbeyaz, S.A.; Kurt, R.E.; Eren, S. Adjacency–based facility layout optimization for shipyards: A case study. J. Ship Prod. Des. 2023, 39, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, U.; Ambarita, M.B. Production layout improvement by using line balancing and Systematic Layout Planning (SLP) at PT. XYZ. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 309, 012116. [Google Scholar]

- Suhardi, B.; Juwita, E.; Astuti, R.D. Facility layout improvement in sewing department with Systematic Layout planning and ergonomics approach. Cogent Eng. 2019, 6, 1597412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.L.; Fogliatto, F.S. Planejamento sistemático de layout com apoio de análise de decisão multicritério. Production 2008, 18, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, M.; Naqvi, S.; Atir, M.; Zubair, M.; Shehzad, M.M. Energy Management in a Manufacturing Industry through Layout Design. Procedia Manuf. 2016, 8, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvanesh Kumar, M.; Antony, J.; Cudney, E.; Furterer, S.L.; Garza–Reyes, J.A.; Senthil, S.M. Decision–making through fuzzy TOPSIS and COPRAS approaches for lean tools selection: A case study of automotive accessories manufacturing industry. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2022, 18, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El–Baz, M.A. A genetic algorithm for facility layout problems of different manufacturing environments. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2004, 47, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, T. Cabin placement layout optimisation based on systematic layout planning and genetic algorithm. Pol. Marit. Res. 2020, 27, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T. Construction site layout planning and safety management using fuzzy–based bee colony optimization model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 33, 5821–5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González–Cruz, M.; Martínez, E.G. An entropy–based algorithm to solve the facility layout design problem. Robot. Comput.–Integr. Manuf. 2011, 27, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García–Hernández, L.; Salas–Morera, L.; Garcia–Hernandez, J.A.; Salcedo–Sanz, S.; de Oliveira, J.V. Applying the coral reefs optimization algorithm for solving unequal area facility layout problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 138, 112819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, M.R.; Sahu, D.A.; Shahare, A.R. Design and Development of Simulation Model for Plan Layout. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2017, 3, 446–449. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R. A digital twin–based layout optimization method for discrete manufacturing workshop. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Duan, J.; Zhang, Q. Multi–objective integrated scheduling optimization of semi–combined marine crankshaft structure production workshop for green manufacturing. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 2021, 43, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, E.; Uysal, M.; Alkaya, A.F. Migrating birds optimization: A new metaheuristic approach and its performance on quadratic assignment problem. Inf. Sci. 2012, 217, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnwal, S.; Dharmadhikari, P. Optimization of plant layout using SLP method. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 5, 3008–3015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.S. On fuzzy preference relation in group decision making. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2005, 82, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Shao, L.; Zheng, J.; Yang, R. Workshop layout optimization method based on sparrow search algorithm: A new approach. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2024, 41, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Factors Considered | Results Obtained | Positive Sides | Limitations | Scope for Further Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fahad et al. [19] | Environmental and economic goals | Improve transportation efficiency and reduce lighting energy consumption | Achieve a win–win situation for the economy and environmental protection | The actual scenarios such as equipment failure and workers’ efficiency were not taken into consideration | Establish a cost–benefit model to provide enterprises with a basis for economic decision–making. |

| Bhuvanesh et al. [20] | Transportation distance and waiting time | Shorten the production cycle and reduce the transportation distance | Simplify the framework and optimize the production process | Lack of economic analysis and reliance on experts to allocate weights | Introduce multi–method comparison |

| E–Baz. [21] | Production volume, transportation route, and equipment spacing | The algorithm performs stably and effectively reduces the handling cost | Algorithm innovation enhances search capabilities | Large–scale problems take a longer time | Introduce multi–objective optimization and construct a comprehensive optimization model |

| Su Sd et al. [22] | Take the circulation intensity and adjacency intensity of the cabin as the core objectives | Significantly improve circulation efficiency and functional adjacency | Introduce the SLP method for solving factory layout into ship design | Practical constraints such as weight distribution and equipment installation were not taken into account | Apply the method to complex ship types such as industrial ships to verify their universality |

| Nguyen et al. [23] | Actual constraint conditions, and multi–objective optimization | Verify through cases that the algorithm performs well in terms of cost and other aspects | It balanced multiple conflicting targets and provided a reference plan for the construction layout | The complex factors of noise attenuation were not considered | Explore the optimization ability of the algorithm in the dynamic construction environment |

| Gonzalez–Cruz et al. [24] | Consider the main attributes and the relationships among various elements | The entropy algorithm performs better in aspects such as reducing transportation distances | Introduce the concept of entropy into the optimization of facility layout | This algorithm has not been extended to the actual scenarios in two–dimensional or three–dimensional space at present | Test the universality of the algorithm in complex industrial scenarios |

| Garcia–Hernandez et al. [25] | With the material flow cost as the core | The algorithm performs well in small– and medium–sized instances | It has the potential for expansion in multi–objective optimization and dynamic scenarios | The performance of the algorithm depends on the adjustment of empirical parameters | Explore the variants of the algorithm to optimize the convergence speed and global search ability |

| Korde et al. [26] | Limitations of physical space and equipment size | Reduce the distance of logistics transportation and lower costs | The validity of the case verification method can be extended to actual scenarios | Ignore the randomness of actual production | Multi–dimensional indicators are considered in the design to achieve comprehensive optimization |

| Distance Between Work Units | |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 0.8 | |

| 0.6 | |

| 0.4 | |

| 0.2 | |

| 0 |

| Non–Logistics Level | Expressing Relationship | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Extremely desirable | 4 |

| E | Very desirable | 3 |

| I | Desirable | 2 |

| O | Indifferent | 1 |

| U | Unimportant | 0 |

| X | Undesirable | −1 |

| No | Work Unit Name | Length (m) | Width (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raw material area | 16 | 12 |

| 2 | Parts area | 12 | 12 |

| 3 | Cutting area | 14 | 12 |

| 4 | Welding area | 10 | 12 |

| 5 | CNC area | 14 | 12 |

| 6 | Machining area | 14 | 12 |

| 7 | Bending area | 8 | 12 |

| 8 | Heat treatment area | 10 | 12 |

| 9 | Polishing area | 12 | 12 |

| 10 | Painting area | 8 | 12 |

| 11 | Waste area | 6 | 12 |

| 12 | Semi–finished product area | 10 | 12 |

| 13 | Assembly area | 8 | 12 |

| 14 | Finished product area | 14 | 12 |

| Unit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 46.77 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.651 | 2 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.049 | 0 | 16.689 | 1.965 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.067 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17.841 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.173 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17.601 | 0 | 0.51 | 10.158 | 0 | 5 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16.338 | 0 | 0 | 0.468 | 0 | 5.793 | 6 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.965 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.428 | 5.91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27.774 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.223 | 1.551 | 10 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43.746 | 12 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.365 | 0 | 13 |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Unit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No | Work Unit Name | X | Y |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raw material area | 65 | 43 |

| 2 | Parts area | 63 | 25 |

| 3 | Cutting area | 47 | 43 |

| 4 | Welding area | 21 | 43 |

| 5 | CNC area | 8 | 25 |

| 6 | Machining area | 38 | 25 |

| 7 | Bending area | 33 | 43 |

| 8 | Heat treatment area | 23 | 25 |

| 9 | Polishing area | 7 | 43 |

| 10 | Painting area | 18 | 7 |

| 11 | Waste area | 51 | 25 |

| 12 | Semi–finished product area | 6 | 7 |

| 13 | Assembly area | 29 | 7 |

| 14 | Finished product area | 43 | 7 |

| Work Unit Pairs | Original Layout Scheme | Scheme Obtained by GA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by SSA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by WSO Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| 213 | 73 | 13 | 33 | 52 |

| 3–4 | 72 | 40 | 32 | 26 |

| 3–6 | 35 | 20 | 17 | 27 |

| 3–7 | 60 | 14 | 20 | 14 |

| 3–11 | 27 | 51 | 26 | 22 |

| 4–5 | 20 | 15 | 15 | 31 |

| 4–7 | 12 | 46 | 12 | 12 |

| 4–9 | 25 | 31 | 36 | 14 |

| 5–8 | 67 | 42 | 21 | 15 |

| 5–9 | 41 | 16 | 21 | 19 |

| 5–11 | 43 | 26 | 37 | 43 |

| 5–12 | 32 | 50 | 40 | 20 |

| 6–8 | 50 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| 6–11 | 26 | 35 | 43 | 13 |

| 6–13 | 37 | 29 | 58 | 27 |

| 9–10 | 74 | 13 | 13 | 47 |

| 10–12 | 47 | 21 | 24 | 12 |

| 10–13 | 61 | 27 | 24 | 11 |

| 12–13 | 22 | 12 | 12 | 23 |

| 13–14 | 14 | 23 | 14 | 14 |

| Total | 856 | 557 | 531 | 475 |

| Work Unit Pairs | Original Layout Scheme | Scheme Obtained by GA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by SSA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by WSO Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2–13 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| 3–4 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 3–6 | 2.4 | 3 | 3 | 2.4 |

| 3–7 | 1.2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3–11 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| 4–5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.6 |

| 4–7 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 1 |

| 4–9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 5–8 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 5–9 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.6 | 2 |

| 5–11 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| 5–12 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 6–8 | 2.4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 6–11 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1 |

| 6–13 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| 9–10 | 0.8 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 10–12 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2 |

| 10–13 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 12–13 | 2.4 | 3 | 3 | 2.4 |

| 13–14 | 4 | 3.2 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 30.6 | 37.6 | 38.2 | 38.2 |

| No | Length (m) | Width (m) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35 | 10 |

| 2 | 60 | 10 |

| 3 | 40 | 9 |

| 4 | 15 | 9 |

| 5 | 55 | 10 |

| 6 | 90 | 23 |

| 7 | 30 | 9 |

| 8 | 120 | 9 |

| 9 | 90 | 12 |

| 10 | 60 | 12 |

| 11 | 55 | 25 |

| 12 | 60 | 42 |

| 13 | 90 | 42 |

| 14 | 55 | 10 |

| 15 | 55 | 30 |

| Work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 31.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28.21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.87 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38.41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 8.06 | 0 | 24.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35.39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43.45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54.8 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.5 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Work Unit Pairs | Original Layout Scheme | Scheme Obtained by GA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by SSA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by WSO Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 25.5 | 72.5 | 19.5 | 27.5 |

| 2–5 | 93.5 | 29.5 | 15.5 | 28.5 |

| 3–4 | 225.5 | 166.5 | 30.5 | 30.5 |

| 4–5 | 38.5 | 78.5 | 38.5 | 38.5 |

| 5–6 | 85 | 37 | 72 | 39 |

| 6–7 | 90 | 60 | 70 | 70 |

| 7–8 | 119 | 78 | 86 | 51 |

| 7–9 | 174.5 | 104.5 | 89.5 | 55.5 |

| 7–11 | 116.5 | 70.5 | 37.5 | 53.5 |

| 8–9 | 91.5 | 26.5 | 30.5 | 24.5 |

| 8–11 | 67.5 | 87.5 | 73.5 | 68.5 |

| 9–10 | 90 | 33 | 28 | 55 |

| 9–13 | 108 | 63 | 42 | 63 |

| 9–15 | 100.5 | 84.5 | 56.5 | 44.5 |

| 10–13 | 72 | 30 | 70 | 88 |

| 12–13 | 123 | 78 | 78 | 78 |

| Total | 1610 | 1099.5 | 837.5 | 815.5 |

| Work Unit Pairs | Original Layout Scheme | Scheme Obtained by GA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by SSA Algorithm | Scheme Obtained by WSO Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 2 | 1.6 | 2 | 2 |

| 2–5 | 1.6 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3–4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4–5 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 5–6 | 2.4 | 3 | 2.4 | 3 |

| 6–7 | 2.4 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 7–8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 7–9 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 7–11 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2 | 2 |

| 8–9 | 2.4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 8–11 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 9–10 | 2.4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 9–13 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 4 | 3.2 |

| 9–15 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 4 | 4 |

| 10–13 | 2.4 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 12–13 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Total | 30.6 | 34.2 | 35.8 | 36 |

| Layout | Transportation Distance | Non–Logistics Relationship | Rank_Transportation Distance | Rank_Non–Logistics Relationship | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 815.5 | 36 | 1 | 8.5 | −7.5 | 56.25 |

| 2 | 836.5 | 36.6 | 2 | 10 | −8 | 64 |

| 3 | 837.5 | 35.8 | 3 | 7 | −4 | 16 |

| 4 | 893.5 | 36 | 4 | 8.5 | −4.5 | 20.25 |

| 5 | 967.5 | 35.6 | 5 | 6 | −1 | 1 |

| 6 | 989.5 | 34.8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 7 | 1002.5 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| 8 | 1034.5 | 34.6 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 25 |

| 9 | 1099.5 | 34.2 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 49 |

| 10 | 1610 | 30.6 | 10 | 1 | 9 | 81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, B.; Wei, Y.; Luo, Q.; Zhou, Y. White Shark Optimization for Solving Workshop Layout Optimization Problem. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050268

Guo B, Wei Y, Luo Q, Zhou Y. White Shark Optimization for Solving Workshop Layout Optimization Problem. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(5):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050268

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Bin, Yuanfei Wei, Qifang Luo, and Yongquan Zhou. 2025. "White Shark Optimization for Solving Workshop Layout Optimization Problem" Biomimetics 10, no. 5: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050268

APA StyleGuo, B., Wei, Y., Luo, Q., & Zhou, Y. (2025). White Shark Optimization for Solving Workshop Layout Optimization Problem. Biomimetics, 10(5), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050268