1. Introduction

Dental health is a fundamental component of overall well-being, serving as both an indicator and contributor to systemic health [

1,

2]. Traditional methods for caries detection, such as visual–tactile examination and radiography, often exhibit limitations in sensitivity and specificity, hindering their effectiveness in determining the activity or progression of carious lesions. Advanced diagnostic techniques, including fiber-optic trans-illumination, quantitative light-induced fluorescence, laser fluorescence, electrical conductance measurements, digital radiography, optical coherence tomography, and intraoral scanners, provide more accurate information about carious lesions [

3,

4].

Human–robot collaboration (HRC) is increasingly being integrated into dentistry to improve surgical precision, reduce procedural time, and enhance patient safety. Recent advancements in robot-assisted dental procedures have demonstrated the potential of collaborative robotic systems in dental implant surgery, where robots assist in positioning, drilling, and ensuring the accurate placement of implants [

5]. These robotic systems operate under human supervision and enhance procedural efficiency, minimizing surgical deviations and improving outcomes [

6]. Moreover, semi-autonomous robotic platforms are being developed for oral surgery, utilizing monocular vision-based guidance to assist in delicate dental procedures while maintaining human oversight [

7].

Beyond surgery, collaborative robots play a role in dental prosthetics, orthodontics, and automated diagnostics. AI-driven robotic systems assist in 3D scanning, treatment planning, and prosthesis fabrication, reducing manual workload and increasing accuracy [

8]. Additionally, human–robot interaction (HRI) research in dentistry has focused on improving robotic adaptation to dental practitioners’ workflows, ensuring a smooth integration into clinical practice [

9]. The success of robot-assisted procedures is closely linked to how effectively robots synchronize with human movements—a concept rooted in motor resonance—where the human perception of robot-assisted movements influences real-time collaboration [

10]. As robotic technology in dentistry advances, further refinements in surgical planning, haptic feedback, and AI integration will enhance its applications in complex dental procedures.

For orthodontic treatments, digital orthodontics integrate machine learning algorithms with robotic arms to precise position brackets based on preoperative digital treatment plans. The incorporation of robotic technology in clear aligner production and orthodontic simulations is improving treatment predictability and reducing manual errors [

11]. Robotic assistance is also emerging in endodontic microsurgeries and periodontal procedures, where high precision is required for root canal treatments and soft tissue management. Studies have explored the integration of micro-robotic surgical instruments into endodontic navigation systems, enabling minimally invasive root canal therapy with enhanced accuracy and reduced procedural time [

12].

Another application for dental robots lies in the advancements in robot-assisted prosthodontics including the development of robotic crown lengthening surgery systems. These systems utilize robotic arms and AI-powered software to perform precise incisions and tooth adjustments, enhancing aesthetic and functional outcomes for prosthetic restorations [

13]. AI-driven robotic platforms are also being used for automated tooth preparation and prosthesis fabrication, streamlining the process, and improving consistency in customized dental restorations [

14]. On the other hand, robotic dentistry is developing into remote procedures via teledentistry platforms, where robotic systems can be controlled remotely for diagnostic and treatment assistance. This is particularly useful in rural areas where access to dental professionals is limited, enabling remote-controlled robotic interventions for emergency cases [

15].

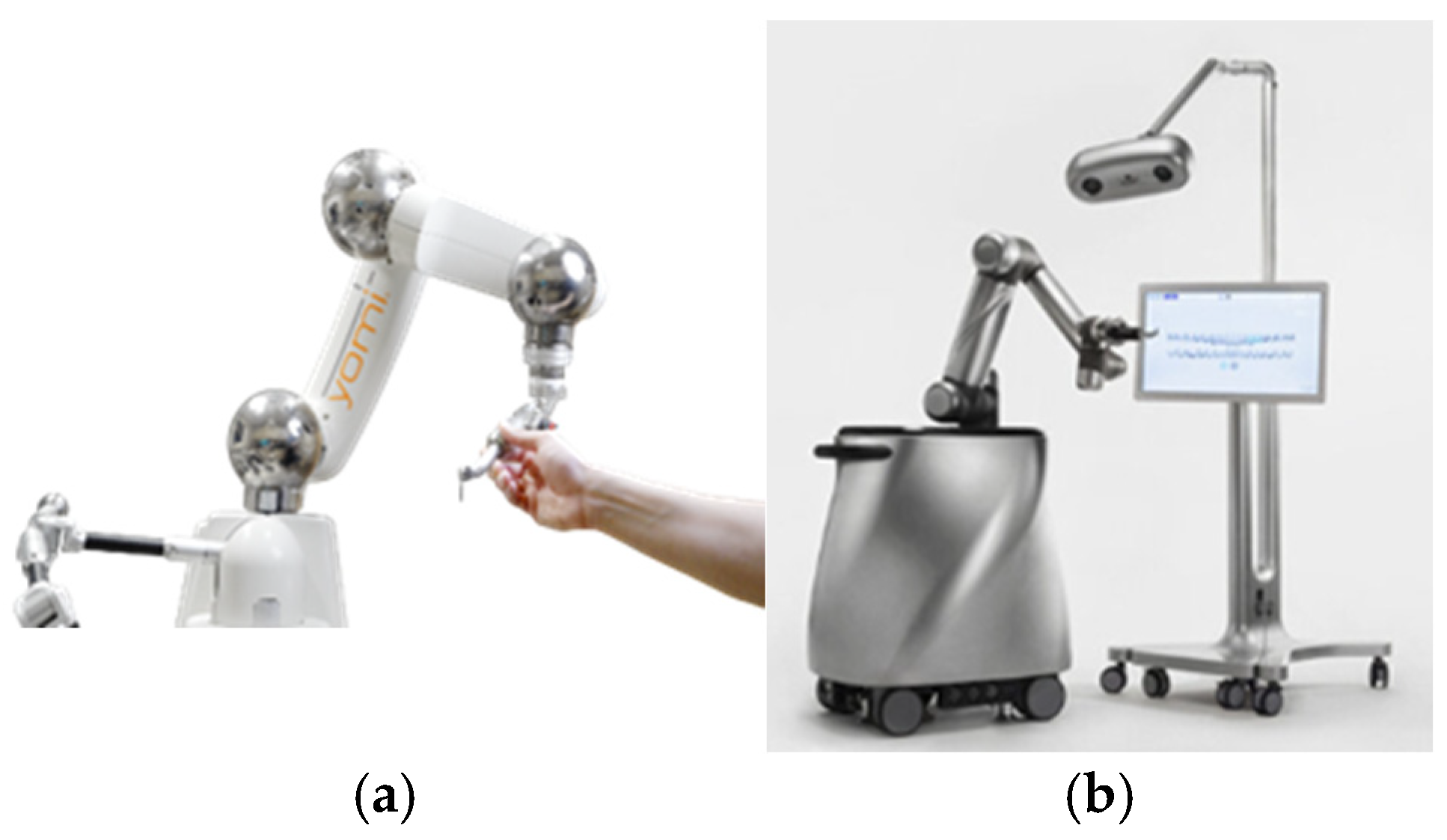

Examples of dental robots include Yomi, the first FDA-approved robotic system for dental implant surgery. Yomi assists in preoperative planning and real-time intraoperative guidance, ensuring greater accuracy in implant placement while allowing for dynamic adjustments based on patient-specific anatomical variations [

16]. Research has demonstrated that Yomi improves surgical precision, reduces chair time, and minimizes the risk of complications compared to freehand implant placement methods [

17]. Another example is The Autonomous Dental Implant Robotic (ADIR) system that has been developed to provide fully automated implant placement capabilities. Unlike Yomi, which operates under human supervision, ADIR is designed for the autonomous execution of implant drilling and placement, significantly reducing human intervention [

18]. Studies indicate that ADIR offers high accuracy in edentulous patients, particularly in full-arch rehabilitation and flapless implant surgeries [

19,

20]. Both robotic dental systems are shown in

Figure 1.

From previous examples, dental robots can be classified according to their mechanical manipulator, hardware configuration, type of perception, position/force controller, and level of autonomy [

16]. Many examples of dental robots use off-shelf industrial manipulators with their integrated controllers. Dental robots like Theta [

21], Dcarer [

22], Remebot [

23], and Yakebot [

24] use Universal robot manipulators [

25] as their main mechanical arm. This is somehow limiting the possibility of open-source upgrades in software and hardware. Additionally, these robots exhibit levels 1 and 2 of autonomy during operations.

In level 1 autonomy, the robot provides real-time guidance and positional constraints while requiring the operator to continuously control its movements. This collaborative framework allows the surgeon or dentist to retain full control, with the robot acting as an assistive mechanism to enhance precision and prevent deviations from predefined safe zones. An example of such a system is the Mako Smart Robotics platform (Stryker Corporation, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). In contrast, level 2 autonomy enables the robot to perform specific tasks independently based on discrete instructions from the operator and preprogrammed procedural steps. Here, the operator interacts with the system intermittently rather than continuously, allowing the robot to autonomously execute movements such as drilling or implant positioning.

From previous literature, the necessity for developing customizable and upgradable robotic manipulator systems with robust controllers for dental assistance was proven. To develop a surgical robotic assistant, the robotic arm must mimic human dentist kinematic movements during reaching tasks for object handling. Thus, for a robotic manipulator to be utilized, a robust position controller must be used to control these trajectories using the starting and end points as input data. These “biologically inspired” trajectories, referred to as “human-like,” are subsequently used for the trajectory planning of a serial robotic arm, which functions as a human substitute in our proposed collaboration scenario.

Several AI-based controllers are used for robotic manipulators. Adaptive Neural Network-Based Control (ANNBC) has been extensively applied to robotic manipulators to enhance their adaptability and performance in uncertain environments. The Adaptive Neural Network-Based Control (ANNBC) approach is designed to enhance the trajectory tracking performance of robotic manipulators by dynamically compensating for model uncertainties and external disturbances. Unlike traditional model-based controllers, which rely on the precise knowledge of system dynamics, ANNBC employs a neural network to approximate unknown nonlinearities in real-time.

Notable implementation is proposed by Tianli Li et al. [

26], where they presented an ANN control scheme integrated with a disturbance observer to achieve precise trajectory tracking in robotic manipulators facing external disturbances and dynamic uncertainties. Another adaptive approach is presented by Yang et al. [

27], who proposed an Adaptive Neural Network Control approach that utilizes dual neural networks to compensate for both kinematic and dynamic uncertainties. The controller is designed to quickly converge and achieve high accuracy, enhancing the manipulator’s adaptability and performance. Tien Pham et al. [

28] proposed a controller that integrates neural networks (NNs) with dynamic surface control (DSC) to enhance tracking accuracy and stability. The Lyapunov-based adaptation ensures system stability while compensating for unknown system dynamics in real time.

Despite significant progress in dental robotics, current platforms face three major gaps. First, most existing systems (e.g., Yomi, ADIR, Theta, and Yakebot) are adapted from industrial robotic arms, limiting open-source customization and constraining clinical versatility. Second, many rely on preprogrammed guidance at autonomy levels 1 or 2, which restricts adaptability in dynamic clinical environments. Finally, robust controllers that can handle modeling uncertainties, patient variability, and real-time disturbances remain underexplored. These gaps underscore the need for compact, customizable dental robots equipped with adaptive AI-based control strategies.

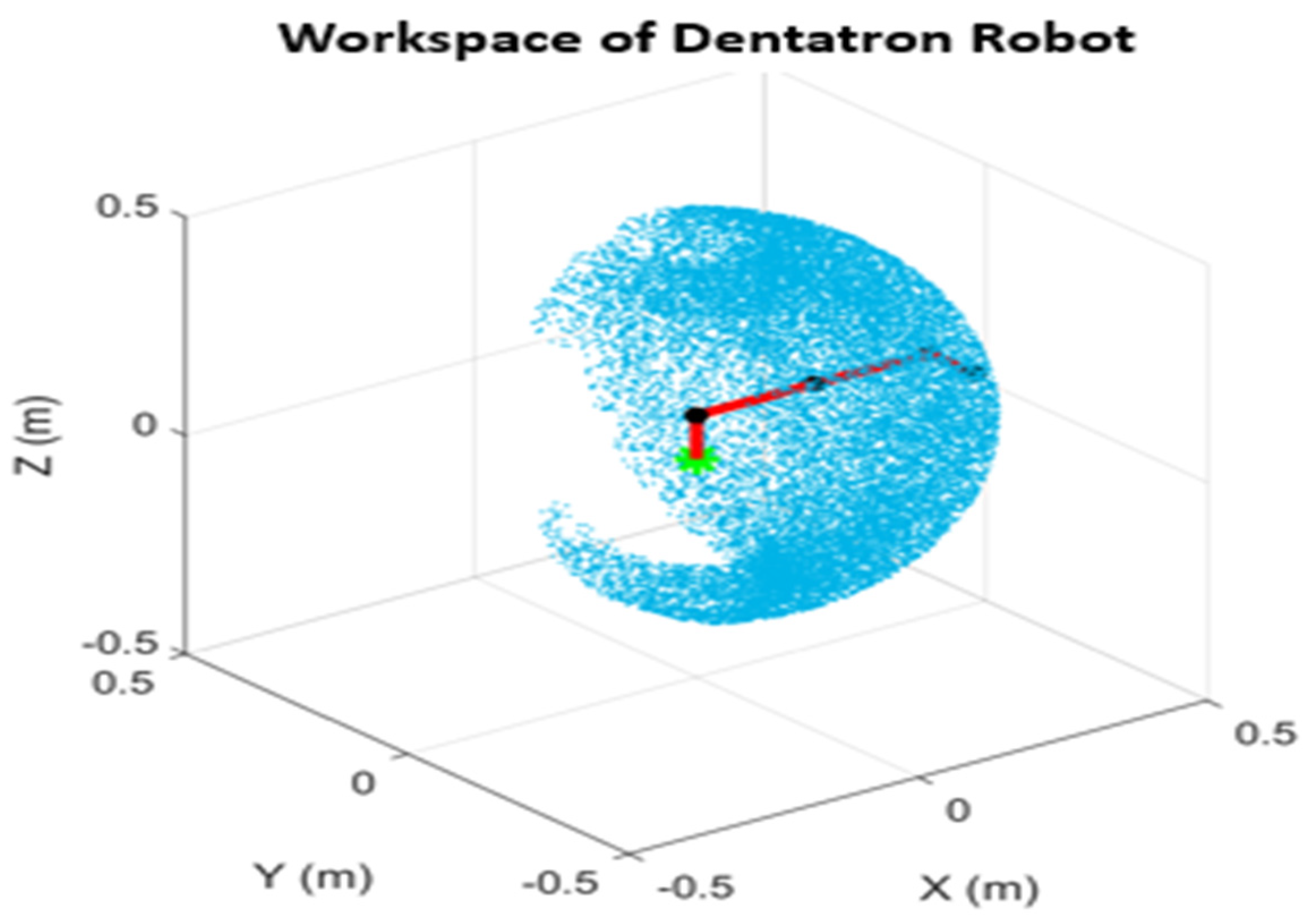

In this paper, a new robotic manipulator is presented for dental care. It is a compact, versatile robot named “Dentatron”. The robot is custom designed, manufactured, and controlled for dental applications. For position control of its joints, two robust controllers are proposed, discussed, and compared. The first one is a model-based computer torque controller, where the mathematical model is derived and an adaptive component of the controller continuously estimates unknown parameters such as payload variations or friction effects, adjusting control efforts accordingly. However, its effectiveness relies on the accuracy of the dynamic model. The model-free adaptive control approach in this paper is a Neural Network Adaptive Controller artificial (NNAC) that dynamically learns the system behavior without requiring an explicit mathematical model for the robot.

The primary aim of this study is therefore to design, model, and control Dentatron as a novel 4-DOF dental robotic manipulator specifically tailored for dental applications. Two complementary control strategies are implemented and compared: a model-based Computed Torque Controller (CTC) and a model-free Neural Network Adaptive Controller (NNAC). In addition, a Fuzzy Logic Controller (FLC) is tested as a benchmark for smooth trajectory execution. In this work, biomimetic trajectories are motion profiles designed to mimic the smooth, coordinated, and physiologically natural movements found in human motor control. These trajectories were used as a unified reference for the CTC, FLC, and NNAC controllers, ensuring that all comparisons reflected tracking ability rather than differences in input signals. By imposing smooth, human-like motion profiles, the trajectory creates a realistic and clinically appropriate test that prevents abrupt movements in the dental workspace. This setup allows the simulations to fairly evaluate how effectively each controller reproduces dentist-like kinematics in terms of tracking error, overshoot, settling time, and overall motion quality. The objectives are fourfold: (1) to develop a compact and versatile robotic arm optimized for the geometric and ergonomic constraints of the dental workspace; (2) to implement and compare three advanced controllers—Computed Torque Control (CTC), Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC), and Neural Network Adaptive Control (NNAC)—under simulated dental tasks; (3) to evaluate tracking accuracy, transient response, and robustness across step and trajectory tasks; and (4) to assess the potential of adaptive neural controllers for future clinical integration in robotic dentistry.

3. Results, Verification, and Discussion

The robot is modeled using the equations from

Section 2 to calculate its inverse kinematics and inverse dynamics. To validate the proposed control approach, simulations were conducted using MATLAB for the Dentatron robotic arm. The robot joints were controlled using NNAC, FLC, and CTC controllers to test and evaluate its performance under two case studies. Both are displayed in the following subsections.

3.1. Joint Position Tracking

The Dentatron robot was subject to reference angles for all joints. For the first link, the desired trajectory is to 60 deg. As shown in

Figure 8, all three controllers converge to the desired position but with distinct transient behavior. NNAC (red) reaches the setpoint fastest with a very small overshoot (≈1–2°) and short settling time. FLC (magenta) shows a slower, monotonic rise with virtually zero overshoots and a smooth, critically damped profile. CTC (green) is the most aggressive: it exhibits a pronounced overshoot (peaking around ~80°), followed by an undershoot (~55°) and damped oscillations before settling near 60°. Overall, NNAC offers the quickest accurate tracking, FLC provides the smoothest/no-overshoot response, and CTC incurs the largest transient excursion.

For the second link, all controllers move the link toward the −10° target but with different transients. NNAC (red) gives a smooth, monotonic decay with no overshoot and zero steady-state error, settling close to the setpoint within a few seconds. FLC (green) exhibits a noticeable overshoot (≈10–15%, down to about −11.5°) and a lightly damped oscillation before converging; it settles around 12–15 s near the target. CTC (magenta) reacts fastest initially but shows a brief undershoot/peaking and then maintains a residual offset (~1° at 20 s), indicating steady-state error. Overall, NNAC provides the most accurate and well-damped tracking, FLC converges with moderate overshoot, and CTC is quick but the least accurate at steady state, as shown in

Figure 9.

For the third link, all controllers reach the setpoint but with different transients. NNAC (red) rises fastest and settles near 60° within ~1–1.5 s with negligible overshoot. CTC (magenta) is aggressive: it produces a large overshoot to ≈85° (~40% over), then an undershoot to ≈50°, followed by lightly damped oscillations that decay and settle around 10–12 s. FLC (green) is the smoothest but slowest, exhibiting a monotonic, no-overshoot rise that converges to 60° after ~7–9 s. Overall, NNAC delivers the quickest well-damped tracking, FLC prioritizes smoothness, and CTC incurs the largest transient excursions, as shown in

Figure 10.

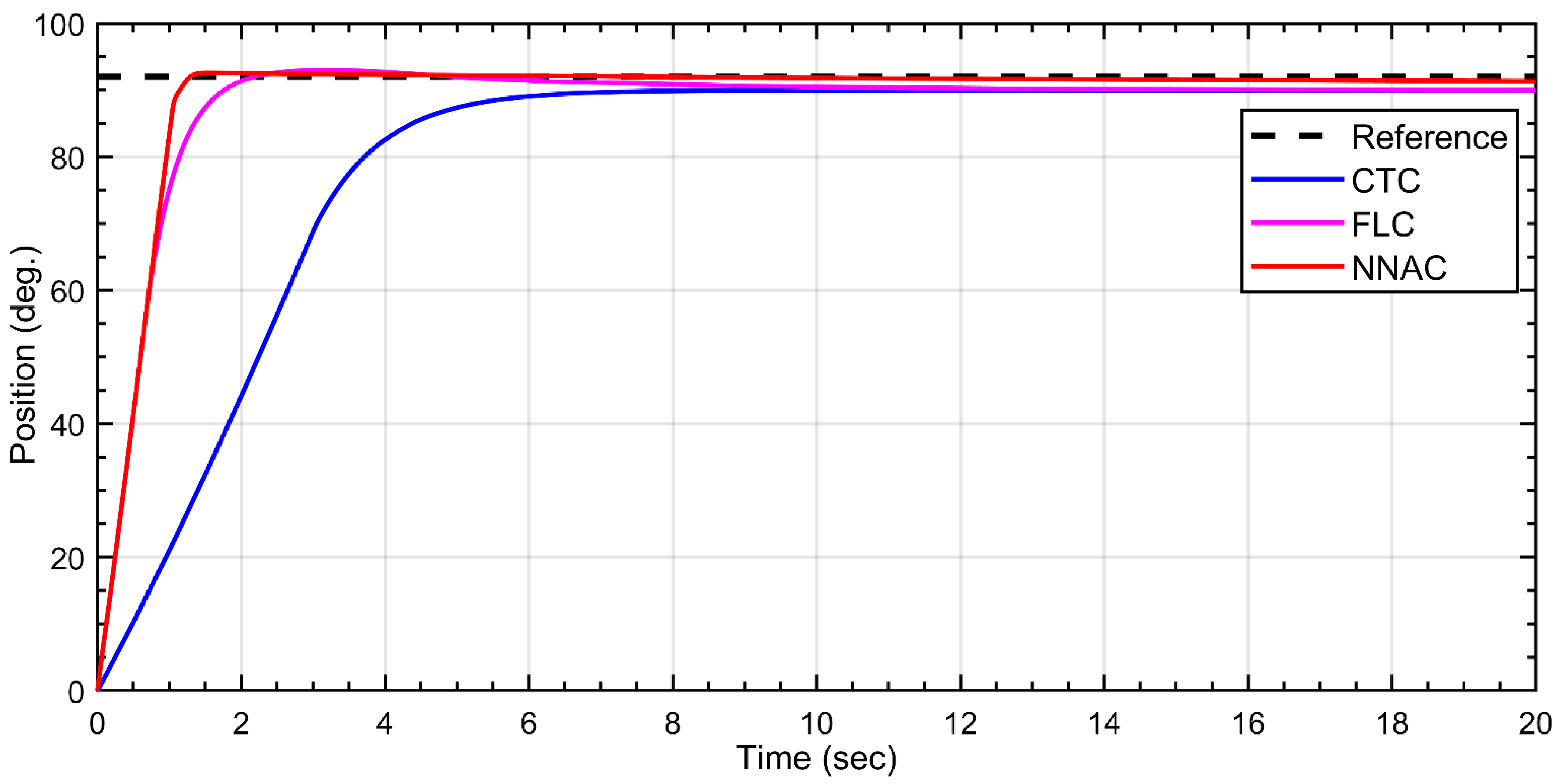

For the fourth link, all controllers reach the target angle with negligible steady-state error but differ in transient speed as shown in

Figure 11. NNAC (red) achieves the fastest rise and settles in ≈2 s with only a very small overshoot (<~1–2°). FLC (green) is slightly slower, showing a minor overshoot followed by a short decay, settling in ≈3 s. CTC (magenta) is the slowest: it follows a near-linear ramp and reaches the neighborhood of the setpoint only after ≈6–8 s with no overshoot but the longest settling time. Overall, NNAC provides the quickest well-damped tracking, FLC is close with mild overshoot, and CTC is the most sluggish.

3.2. Robot Trajectory Tracking

To evaluate the performance of the dental robot arm in executing a predefined 3D trajectory, a sequence of five waypoints was programmed to guide the end effector through a path in Cartesian space. The trajectory was designed to simulate controlled motion. The waypoints, defined by their X, Y, and Z coordinates (in meters) at discrete time steps, are presented in

Table 3.

The trajectory consists of three unique positions: the initial and final point P1, an intermediate point P2, and a lowest point P3. The path follows the sequence P1 → P2 → P3 → P2 → P1, forming a V-shaped trajectory confined to a single plane in 3D space. The plane’s equation, derived from the waypoints, is approximately

For the X-position, as shown in

Figure 12, the three controllers follow the desired X-trajectory over 0–4 s, including two peaks (≈1 s and ≈3 s) and a valley (≈2 s). The zoomed area highlights the sharp direction changes. NNAC (red, dashed) achieves the closest match to the reference with the smallest corner error and fastest decay of the small residual oscillations (errors on the order of a few millimeters). FLC (green, dotted) tracks well with slightly rounded corners and modest ripple. CTC (magenta) shows the largest overshoot/undershoot and oscillatory ripple at the corners, though it remains close to the reference elsewhere. Overall, NNAC provides the highest tracking accuracy, followed by FLC, while CTC exhibits the most transient oscillations.

Figure 13 shows that the three controllers follow the triangular Y-trajectory over 0–4 s; zoomed insets highlight the three sharp corner transitions. NNAC (red, dashed) gives the closest match to the reference with the smallest corner error and fastest decay of the small ripples after each turn. FLC (green, dotted) tracks well with slightly larger corner rounding and mild residual ripple. CTC (magenta) shows the largest overshoot/undershoot at the corners and the most noticeable post-corner oscillations before reconverging. Overall, NNAC achieves the highest Y-tracking fidelity, FLC is a close second, and CTC exhibits the most transient oscillations.

The three controllers track the triangular Z-trajectory over 0–4 s, where the three corner transitions (~0.95 s, ~2.25 s, and ~3.7 s) were magnified. NNAC (red, dashed) follows the reference most closely with the smallest corner error and fastest decay of the millimeter-scale ripples after slope changes. FLC (green, dotted) is a close second—good accuracy with slightly larger corner spikes and mild ringing. CTC (magenta) exhibits the largest overshoot/undershoot at the corners and the most persistent post-corner oscillations before reconverging. Overall ranking in Z is as follows: NNAC ≳ FLC > CTC for corner handling and ripple suppression. The tracking along the

Z-axis is shown in

Figure 14.

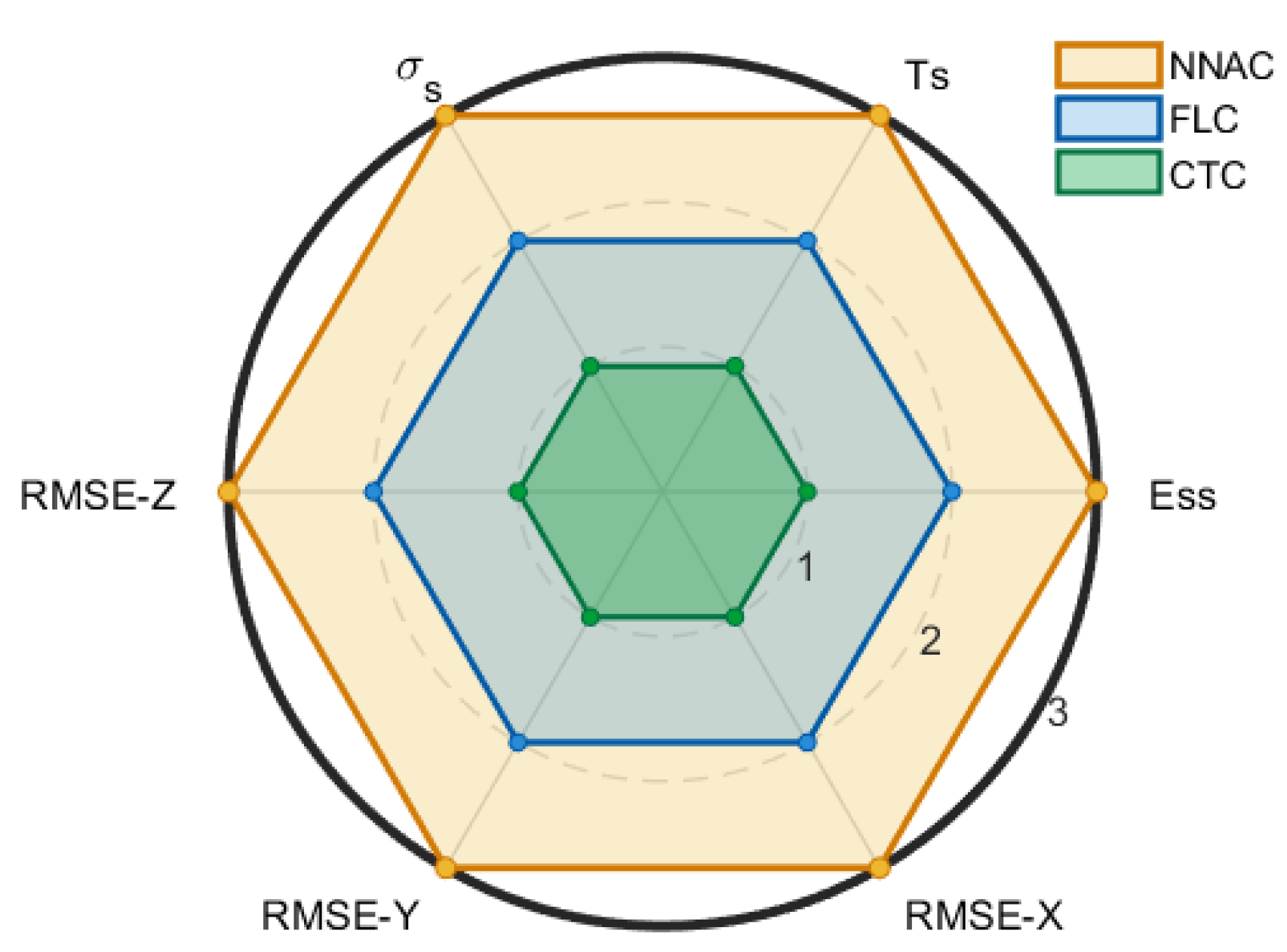

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The performance of the three controllers—Neural Network Adaptive Control (NNAC), Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC), and Computed Torque Control (CTC) was evaluated using a common set of accuracy and transient response metrics. For the step responses of links 1–4, percentage overshoot (OS), settling time (Ts, defined within a ±2% band), and steady-state error (Ess) were measured. For trajectory tracking, the root mean-square error (RMSE) in the X, Y, and Z directions was calculated.

A subject design was adopted within, whereby each trial was assessed under all three controllers. Tests of normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and sphericity (Mauchly) were performed prior to statistical analysis. When the assumptions were met, a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was applied, with Greenhouse–Geisser correction where necessary, followed by Holm-adjusted post hoc comparisons. When the assumptions were not satisfied, the Friedman test with Conover–Holm pairwise comparisons were employed. Effect sizes were expressed as partial η2 for ANOVA and Kendall’s W for Friedman tests. A two-sided significance level of α = 0.05 was used throughout.

Figure 15 presents the results in the form of a radar (spider) chart with six spokes (OS, Ts, Ess, RMSE-X, RMSE-Y, and RMSE-Z). On each spoke, qualitative scores were assigned based on controller ranking: rank 1 was mapped to a score of 3, rank 2 to a score of 2, and rank 3 to a score of 1 (i.e., score = 4 − rank). Consequently, a larger radius on the chart corresponds to superior performance.

The outer polygon was consistently traced by NNAC, reflecting minimal overshoot, the shortest settling times, near-zero steady-state error, and the lowest RMSE values in X, Y, and Z, with rapid error decay around the corners. The intermediate polygon was formed by FLC, which generally produced smooth responses without overshoot but exhibited slower settling and slightly higher RMSE than NNAC. The inner polygon was occupied by CTC, characterized by larger overshoot or undershoot and more persistent oscillations after corners.

The clear and uniform separation between polygons across all spokes suggests that practically meaningful differences exist, with NNAC outperforming CTC substantially and FLC to a moderate degree. Once numerical time-series data are formally analyzed, these patterns are expected to yield statistically significant results—especially for OS and Ts (partial η2 > 0.14 or Kendall’s W > 0.5)—as well as moderate to large improvements in RMSE after Holm correction. From an operational perspective, NNAC provides faster and tighter tracking with reduced transient excursions, FLC ensures smooth non-overshooting motion but at the expense of speed, while CTC requires precise tuning to mitigate large excursions and residual oscillations.

In summary, the results showed that Neural Network Adaptive Control (NNAC) consistently provided superior performance compared with Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC) and Computed Torque Control (CTC). In step tracking tasks across four joints, NNAC achieved the fastest convergence (1–2 s), minimal overshoot (~1–2°), and negligible steady-state error. FLC responses were smoother and nearly overshoot-free but slower (3–9 s), while CTC exhibited aggressive transients with overshoot up to 40% and persistent oscillations. For 3D trajectory tracking, NNAC reduced root mean square errors (RMSE) to <3 mm in X/Y/Z, outperforming FLC (≈4–5 mm) and CTC (6–8 mm). Qualitative ranking indicated consistent performance differences, with NNAC ranking highest across overshoot, settling time, and RMSE metrics. These results highlight NNAC as the most robust and accurate controller for the Dentatron platform.

These results, when compared to other dental clinical systems, show that the acceptable positional error depends on the task. For implant placement robots such as Yomi, the reported accuracy is 1.0–1.5 mm at the drill tip. For navigation templates and optical scanning tools, errors in the range of 2–4 mm are commonly tolerated. Since Dentatron is designed for positioning and scanning rather than drilling, an RMSE below 3 mm falls within clinically acceptable limits. This supports the claim that the NNAC controller, when applied to the Dentatron robot model, provides clinically adaptable motion accuracy.