Building on the global momentum generated by student-led movements such as

Rhodes Must Fall Movement1,

Why Is My Curriculum White2, and

Black Lives Matter, a wave of student-led appeals, backed by staff support, issued calls for the decolonization of Belgian higher education in six universities (

Adhikari-Sacré et al. 2020;

de Oliveira Andreotti 2015;

Begum and Saini 2019;

Mbembe 2016). Out of these initiatives, a dialogic culture developed in which students, staff, rectors, universities, inter-university councils, and federal governments all became participants in an ongoing negotiation over the meaning and practice of decolonization.

Belgium’s decolonial discourse in higher education emerges within a peculiar context of national amnesia (

Van Nieuwenhuyse 2014). Belgian scholars have argued that Belgium has made a concerted effort to actively forget its colonial presence on the African continent (

Ceuppens 2004;

Goddeeris 2015). After the Democratic Republic of the Congo gained independence in 1960, Belgium swiftly dismantled its two main colonial institutions that had mediated transnational relations with the DRC (

Ceuppens 2004). By 1963, no academic infrastructure remained to sustain, or critically examine, Belgium’s presence on the African continent (

Vansina 1994). The educational consequence of Belgium’s attempt to erase its colonial past has been the creation of a collective illiteracy among the Belgian population, impeding their ability to understand the contemporary ramifications of the nation’s colonial history (

Ceuppens 2004;

Sacré 2023;

Withaeckx 2019).

This broader intellectual landscape of decolonization builds on foundational critiques of racialization in education and knowledge production.

Fanon (

2008) demonstrated how colonial schooling internalizes racial hierarchies and shapes the psychic life of both colonizer and colonized;

Said (

1995) exposed how Western academic knowledge sustains imperial authority through epistemic othering. Extending these critiques,

Quijano and Ennis (

2000) theory of the coloniality of power and

Mignolo’s (

2011) elaboration of epistemic disobedience show how modern knowledge systems, including universities, continue to reproduce global hierarchies long after formal decolonisation. Complementing this work,

Gilroy (

2003) foregrounded diasporic and transnational formations of racial belonging that universities often fail to register, while

Hall (

2017) reconceptualised race as a “sliding signifier,” showing how its effects persist even when the term is avoided, an insight particularly relevant in Belgian- and Dutch-speaking contexts (

Kanobana 2021;

Sacré and Rutten 2023).

Wekker’s (

2017) notion of “white innocence” further illuminates how European institutions maintain racialized hierarchies through claims of moral neutrality. Scholars such as

Mbembe (

2016) and

Bhambra et al. (

2018), among others, have brought the decolonization of higher education to the forefront of academic and public debate. Their work shows how universities function as key nodes in the reproduction of colonial hierarchies and as crucial sites for rethinking citizenship, knowledge, and belonging.

Internationally, anti-racist and decolonial interventions in higher education are increasingly met with sanctions: ranging from funding cuts to U.S. universities supporting pro-Palestinian rallies to the arrest of students participating in similar protests in Europe (

Abel Woldegabriel 2025;

Della Porta 2025;

Tshishonga 2025). The sanctioning of decolonial and anti-racist interventions shows that universities are not neutral spaces: they are places where racial belonging, political voice, and legitimate knowledge are constantly negotiated. These reactions raise a central question:

which parts of the anti-racist and decolonial discourse trigger institutional defensiveness, and what does this reveal about how universities respond to demands for change?This article addresses this question by examining how decolonial actors use either dialogic or authoritative forms of discourse. This distinction matters. Authoritative discourse tends to silence alternative viewpoints and establish new “truths,” whereas dialogic discourse creates space for questioning, exchange, and mutual transformation. Understanding how these different forms of discourse operate could eventually help us to see how decolonization in higher education can be carried out in ways that do not simply replace one orthodoxy with another but instead remain grounded in dialogue.

While existing scholarship has mapped the political stakes of decolonial work, there remains a need for an analytical framework that explains how decolonial claims unsettle dominant narratives without producing new exclusions. This article takes up that task, focusing on the pedagogical dimension of decolonial discourse: how we speak, listen, and engage when imagining more equitable futures in higher education.

To explore the pedagogical question, I draw on

Bakhtin’s (

1982) framework of dialogic and authoritative discourse, further developed by

Matusov and von Duyke (

2009), to operationalize the discursive tensions within decolonial activism and institutional response. I follow recent scholarship that applies Bakhtinian dialogism to analyze colonial and decolonial discourse (

Brandist 2022;

Rule 2011;

Dimas 2017;

Blackledge and Creese 2014), not as a substitute for decolonial theory but as a tool to render its dialogic dynamics empirically visible. Given the emergence of a dialogic culture around decolonization, including students, staff, rectors, policy councils, and governments, Belgium offers a uniquely fertile context for examining how dialogic mechanisms operate within higher education reform. Drawing on Bakhtin’s framework of dialogic discourse, as adapted to educational research by

Matusov (

2007), this article distinguishes between dialogic and authoritative forms of decolonial civic engagement with racial illiteracy. Accordingly, it addresses the following research question:

How does decolonial discourse in Belgian higher education employ dialogic and authoritative forms of speech to contest racial illiteracy and unsettle racial hierarchies?This contribution is organized as follows. First, it elaborates on the research methodology ‘internally persuasive discourse (IPD)’, which Matusov & Von Duyck developed by translating Bakthin’s theory to educational work. Second, the results are discussed, exploring how decolonial discourse employs internally persuasive discourse (IPD) to critically address institutionalized forms of racial illiteracy. Finally, the discussion discusses how the insights of this research can be translated to the broader decolonial debate and manifestations of racial illiteracy elsewhere.

1. Methodology: Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD)

This contribution utilizes Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of dialogic discourse to analyze the dialogic culture mounted by the decolonial movement around racial illiteracy in Belgian higher education. Bakhtin’s work, particularly his notion of heteroglossia, provides a theoretical framework for understanding how meaning is produced through the interaction of diverse perspectives and languages. Heteroglossia refers to the “

points of view on the world, forms for conceptualizing the world in words, specific world views, each characterized by its own objects, meanings and values” (

Bakhtin 1982, p. 291).

In contrast to heteroglossia, Bakhtin introduces the concept of monoglossia, which represents a corruption of the dialogic nature of discourse. Monoglossia occurs when “

specific languages as points of view become closed or ‘deaf’ to voices of difference,” thereby suppressing the multiplicity of perspectives that characterize heteroglossia (

Bakhtin 1982, p. 272). In a monoglossic environment, discourse is dominated by authoritative voices that claim absolute truth, limiting the potential for genuine dialogue and critical engagement. This shift from a dialogic to a monoglossic discourse can be particularly detrimental in the context of decolonial debates, where diverse perspectives are essential for addressing complex issues of race and justice (

Blackledge and Creese 2014;

Matusov 2007).

Bakhtin argues that Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD) is crucial for subverting monoglossia and restoring the dialogic potential of discourse. Unlike authoritative discourse, which imposes external authority, IPD encourages individuals to engage critically with different perspectives, leading to an internalization of ideas that are personally meaningful rather than externally imposed. Therefore IPD represents the “

intense struggle within ourselves for hegemony among various available verbal and ideological points of view” (

Bakhtin 1982, p. 271).

Bakhtin’s framework offers a valuable lens for analyzing decolonial discourse because it makes visible how meaning is continuously negotiated across asymmetrical relations of power.

Brandist (

2022) used Bakhtinian dialogism to revisit the colonial encounter, showing how colonial knowledge was shaped through the interplay of European and indigenous voices;

Dimas (

2017) applied the framework to academic literacy in Colombia, demonstrating how dialogue and ideology intersect in postcolonial educational spaces; and

Rule (

2011) and

Skaftun (

2019) adapted Bakhtin’s ideas for pedagogical contexts to explore how dialogue can sustain critique within hierarchical institutions. Similarly, studies from China, Thailand, and Turkey (

Chen et al. 2022) show how dialogic pedagogy enables teachers and students in the Global South to contest monologic, Western-centred norms of knowledge.

1.1. Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD)

Matusov (

2007) and

Morson (

2004) implemented Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD) in educational research to analyze dialogic and anti-dialogic discourse. This article draws in particular on

Matusov and von Duyke’s (

2009) framework categorizing IPD into three distinct approaches, each representing different interpretations of the “internal” aspect within dialogic education, and argue that only the one kind of discourse is truly dialogic.

The first approach, which is the most prevalent in educational settings, conceptualizes IPD as the appropriation of another’s words, ideas, approaches, and knowledge, making them one’s own. Here, the “internal” is understood as internal to the individual, reflecting a psychological and personal conviction (

Matusov and Von Duyke 2009, p. 174).

The second approach views IPD as a means for students to establish authorship within a community of practice. In this context, “internal” refers to the discourse practice itself, where persuasion facilitates the student’s integration into a community by adopting its cultural norms and values (

Matusov and von Duyke 2009, p. 174).

The third approach, which Matusov and von Duyke identify as the only truly dialogic form of IPD, treats it as a dynamic process in which participants rigorously test ideas and explore the boundaries of their personally held beliefs. Here, the “internal” is understood as internal to the dialogue itself, characterized by continuous testing and reevaluation of ideas (

Morson 2004, 319).

The methodological focus of this study is to identify and analyze discourses within the decolonial movement that maintain an open semantic structure, enabling ongoing reflection and dialogue. In accordance with Matusov and von Duyke’s framework, only IPD that transforms illiteracy into dialogic inquiry is considered to contribute to a genuine dialogic pedagogy. Identifying decolonial discourse imposing personal beliefs (IPD1) or cultural normativities (IPD2), the study examines how these may inadvertently perpetuate authoritative discourse and therefore qualify as anti-dialogic. By applying this methodological framework, the study seeks to discern the conditions under which decolonial discourse in Belgian higher education can either promote or inhibit the development of racial literacy.

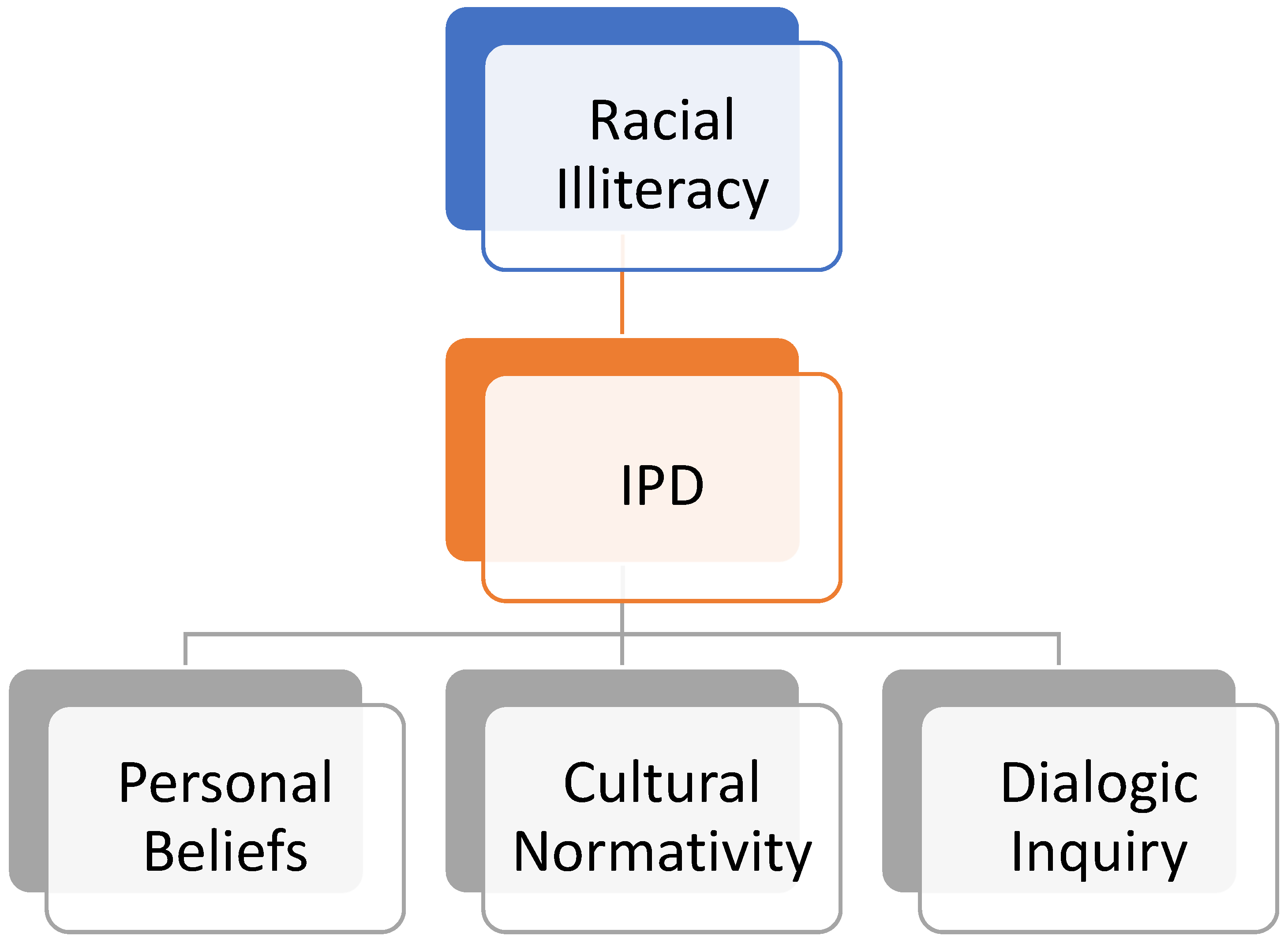

The tree coding structure illustrated in

Figure 1 delineates the three forms of Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD) as they attempt to tackle racial illiteracy within the context of higher education. This framework is central to the analysis, as it categorizes IPD into three distinct forms: Personal Beliefs, Cultural Normativity, and Dialogic Inquiry.

1.2. Analytical Frameworks, Tools and Techniques

To analyze the strategies for overcoming institutional illiteracy, the Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD) framework was employed for deductive coding. This theoretically driven approach uses

Matusov and von Duyke’s (

2009) framework of IPD to guide the identification of patterns, themes, and categories in the data (

Pearse 2019). Specifically, the coding process distinguished between actions suggesting personal beliefs, normative cultural discourse, or dialogic inquiry about the racial illiteracy. The data analysis was carried out in four steps using Nvivo ( version 12) software:

- (1)

Coding discursive instances that signified racial illiteracy within higher education institutions, with particular attention to articulated absences of knowledge, structures, and epistemic frameworks.

- (2)

Identifying and cataloguing the proposed actions and interventions advanced to address these perceived forms of racial illiteracy.

- (3)

Applying the Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD) framework to classify these actions into three analytical categories.

- (a)

Personal beliefs (IPD1):

Passages were coded as IPD1 when the language focused on individual awareness, moral conviction, or behavioural change, often framed through verbs such as realize, unlearn, reflect, become aware, or acknowledge. These formulations appealed to teachers’ or administrators’ self-transformation (e.g., “increasing diversity sensitivity,” “unlearning racism,” or “raising awareness about implicit bias”) and emphasized personal responsibility as the first step toward institutional change.

- (b)

Cultural normativity and discourse (IPD2):

Texts were categorized as IPD2 when they sought to persuade institutions to adopt new norms or policies or when the language invoked implementation, inclusion, institutionalization, policy, representation, measurement, or monitoring. These statements framed racial illiteracy as a problem of governance or institutional culture (e.g., “measuring and monitoring ethnicity,” “institutional responsibility,” or “representation across departments”). The emphasis was on establishing improved cultural standards rather than inviting reciprocal dialogue.

- (c)

Dialogic inquiry (IPD3):

Excerpts were coded as IPD3 when they demonstrated open-ended questioning, reciprocal engagement, or collective reflection, typically marked by verbs such as listen, question, engage, investigate, converse, reflect, or inquire. These formulations treated racial illiteracy as an object of shared exploration rather than a deficit to be corrected (e.g., “listening to Central African partners,” “conversation and reflection about discrimination,” or “questioning deeply rooted structures of knowledge”).

- (4)

I conducted a thematic clustering of the coded actions to synthesize cross-cutting patterns and formulate an integrated interpretation of the findings.

1.3. Data Collection

This contribution draws on a case study of racial illiteracy, which is part of a broader investigation into cultural (il)literacy in Belgium. The dataset was compiled through a combination of document analysis and policy analysis, encompassing records published by universities, students, and journalists.

1.4. Dataset

The study draws on a corpus of thirteen public documents that critically engage with racial illiteracy and the decolonization of higher education in Belgium. The corpus includes open letters, manifestos, and institutional reports authored between 2017 and 2021 by students, lecturers, researchers, university administrators, and policy bodies. These documents articulate contestations around colonial legacies, racism, and the epistemic hierarchies embedded in Belgian higher education. All texts were publicly released as open letters or statements on institutional websites and in academic or professional journals, making them publicly accessible and therefore eligible for analysis without requiring additional ethical clearance.

This study on racial literacy in Belgian higher education is part of a doctoral dissertation on cultural literacy. Parts of this dataset have also been analyzed in a prior publication that focused on racial literacy in student-led activism (

Adhikari-Sacré and Rutten 2021). The present study extends that work by conducting a dialogic discourse analysis of how these same and related documents use internally persuasive discourse to address institutional racial illiteracy within Belgian higher education.

1.4.1. Full Dataset

KASK School of Arts (

2018a). Letter to the curriculum commission of KASK (School of Arts affiliated with Ghent University) addressing a male and Western-dominated curriculum. Ghent: KASK School of Arts (Ghent University Association).

KASK School of Arts (

2018b).

Letter to the dean of KASK addressing racial and gender equality. Ghent: KASK School of Arts (Ghent University Association).

Ghent University (

2021). Response “Decolonize UGent” by the rector and vice-rector. Ghent: Ghent University.

VLIR and CRef (

2021).

Reflection report on Belgian colonial history and the decolonization of Belgian universities. Brussels: Vlaamse Interuniversitaire Raad (VLIR) and Conseil des Recteurs (CRef).

From the full corpus of thirteen public documents, five documents were selected for in-depth qualitative analysis using criterion sampling; these are indicated in bold. The subset includes two open letters from

KASK School of Arts (

2018a;

2018b), the

Decolonize UGent (

2019) student letter, the rectoral response

Decolonize UGent (2020), and the interuniversity reflection report by

VLIR and CRef (

2021).

1.4.2. Limitations and Justifications

This study focuses on decolonial discourse within the Ghent University Association

3, including KASK, the School of Arts institutionally connected to Ghent University. Five key documents from this network were selected for their representational significance and interrelation. Ghent University serves as a microcosm of the national debate, engaging students, lecturers, and administrators across institutional levels. The selected texts were issued sequentially and in dialogue with one another, allowing the analysis to trace the evolution of dialogic and authoritative discourse over time. While decolonial initiatives also exist at other universities, their inclusion would require detailed contextualization beyond this paper’s scope. To situate the case within national developments, the CRef–VLIR reflection report, which synthesizes the decolonization efforts of all Belgian universities and includes Ghent University’s input, is used as a contextual reference. This combination enables a focused yet representative analysis of how decolonial discourse operates in Belgian higher education. Finally, all institutions named in this article (including Ghent University and the Ghent University Association) are cited exclusively through publicly accessible documents. Because the study analyses public communications authored and released by these institutions, no additional institutional consent was required under Ghent University’s ethical guidelines. The study falls under the General Ethical Protocol of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences at Ghent University, which covers research based on publicly available materials.

2. Results: Tackling Racial Illiteracy with Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD)

To capture how the open letters and institutional responses framed racial illiteracy, I conducted a thematic cluster analysis of the lack of knowledge explicitly identified in the texts. Each passage that articulated an absence of knowledge or understanding was coded and paraphrased, allowing for a nuanced interpretation of how epistemic gaps were collectively defined. As many letters and reports referenced each other, their claims were clustered into eleven recurring tropes of racial illiteracy, which appeared across multiple documents and reflected a shared critique of the epistemic hierarchies in Belgian higher education.

2.1. Eleven Identified Racial Illiteracies

These tropes concern: (1) absence of female and racialized authors in the art canon, (2) blind spots about discrimination, exclusion and inequality, (3) Eurocentrism overshadows knowledge about colonization, discrimination and racism, (4) lack of diversity and comprehensive policies to address this, (5) lack of global connectivity of academics whilst educating students in a globalizing world, (6) lack of knowledge about colonial history and globalization, (7) lack of knowledge to maximize inflow and outflow and its relationship to discrimination, (8) lack of skills to engage with students’ trauma of racial violence, (9) lack of statistics about the racial diversity of the student population, (10) little knowledge about Africa among students, and (11) a one-sided narration of colonial history.

Together, these eleven tropes delineate how racial illiteracy manifests as a systemic rather than individual phenomenon, embedded in curricula, policy, pedagogy, and institutional culture. They illustrate how decolonial actors strategically employ the notion of illiteracy to expose the structural exclusions that continue to shape Belgian higher education.

2.2. Discerning Dialogic from Anti-Dialogic Discourse in Dealing with Racial Illiteracy

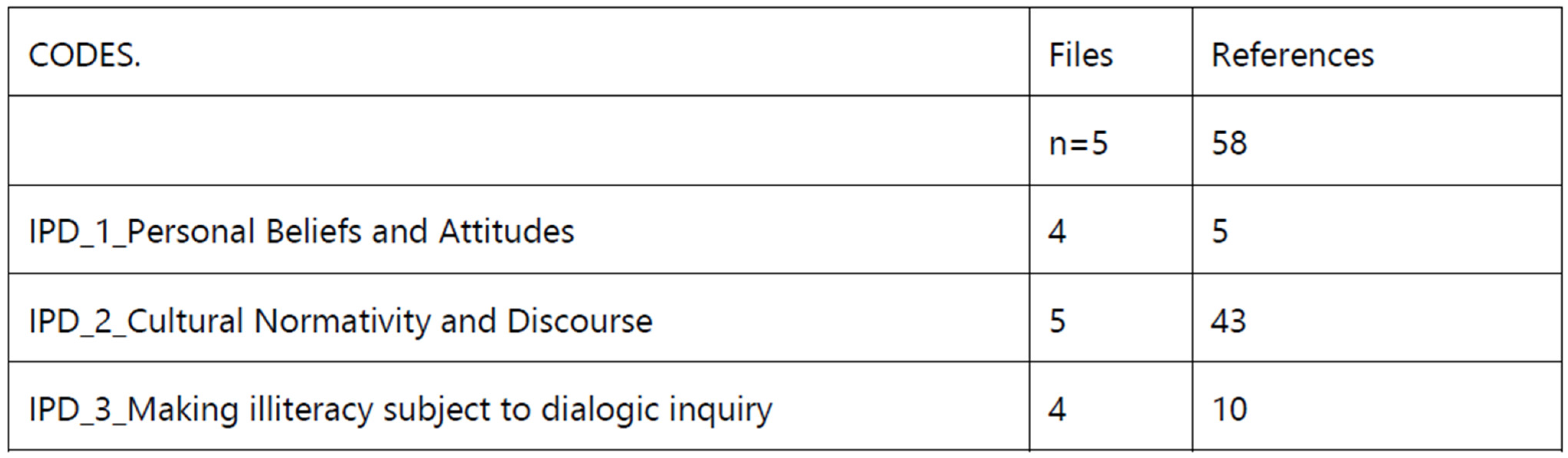

Deductive coding of the five documents related to higher education in Ghent resulted in the following chart.

Deductive coding of the five documents related to higher education in Ghent resulted in three dominant clusters, visualized in

Figure 2. The analysis identified IPD1 (personal beliefs and attitudes), IPD2 (cultural normativity and discourse), and IPD3 (making illiteracy subject to dialogic inquiry), which together account for fifty-eight coded references across the dataset. IPD2 emerged most prominently, appearing in all five documents, while IPD3 occurred less frequently but carried substantial interpretive weight. The prevalence of IPD2—defined as persuading others or oneself to adopt a particular cultural normativity or discourse—suggests that much of the examined material frames racial illiteracy through normative appeals. Instances of IPD3, by contrast, indicate moments where illiteracy itself becomes a topic of dialogic reflection, pointing to the potential for deeper engagement with difference. This distribution illustrates how decolonial discourse within the Ghent University Association navigates the tension between advocacy and dialogue in its pursuit of racial literacy.

2.2.1. IPD1: Personal Beliefs and Attitudes

The first cluster of Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD1) reveals how decolonial discourse in Belgian higher education frames change primarily as a matter of personal conviction and moral awareness among educators. These statements conceptualize transformation as beginning within the individual teacher; the teacher as the ethical agent who must unlearn inherited biases and take responsibility for rewriting history. In this sense, the decolonial project becomes internalized as an exercise in personal awakening rather than an institutional process of reform.

One of the clearest articulations of this belief appears in the KASK letter, which calls upon teachers to assume personal responsibility for reconstructing the curriculum:

“It is up to the teacher to compose the curriculum, to seize the opportunity to rewrite history and ensure balance.”

—Letter to the curriculum commission of KASK

Here, the teacher’s agency is positioned as the central mechanism through which epistemic transformation can occur. The call to “rewrite history” is both symbolic and literal: it signals an expectation that educators take active ownership of decolonial revision. This formulation personalizes institutional illiteracy by transferring the burden of change from structures to individuals, a shift that foregrounds ethical agency but risks reducing systemic reform to a matter of good will.

The same moral framing recurs in the rectoral response from Ghent University, which links anti-racism to individual awareness and sensitivity:

“Racism, discrimination and intolerance have no place and will never be tolerated at our university. At the same time, we are aware that condemning discrimination is not enough to create a safe and inclusive university. We need more awareness and actions to achieve the necessary changes. We do this through active bystander training and implicit bias training.”

—UGent Rectoral Response to “Decolonize UGent” (2020)

While the statement acknowledges the structural nature of exclusion, it ultimately locates the solution in consciousness-raising and behavioural training. The discourse thus reaffirms the moral and psychological dimensions of change, diversity becomes a matter of attitude, cultivated through training and reflection, rather than of epistemic restructuring.

A third illustration expands the locus of awareness from the self to the pedagogical act, arguing that biases and racist legacies should themselves be examined within teaching content:

“Such biases should be given a place within the course content, so that the student is aware of the problematic biases within their discipline. In addition, the problematic and possibly racist background of a researcher must have a place within the course content, all the more so if it had an influence on his theories and research.”

This statement shifts the emphasis from the personal to the curricular, yet it remains framed through individual ethical responsibility; the teacher must recognize, disclose, and correct bias through personal initiative. It reinforces the idea that racial literacy begins with confession, awareness, and pedagogical transparency rather than structural accountability.

Finally, a fourth quote extends this logic to experiential learning, emphasizing the transformative potential of direct engagement with non-Western contexts:

“It is through confrontation with reality on the ground that one truly decentralizes one’s own gaze, questions dominant narratives, and pauses to reflect on one’s own privileges. It is striking that many academics have little connection with non-Western regions, despite training generations for life in a globalized world and being expected to broaden students’ worldview.”

This perspective situates racial literacy as a practice of self-decentering achieved through contact and exchange with the “distant other.” It links decolonial pedagogy to movement, exposure, and humility, an ethics of travel rather than of institutional restructuring. While this mode of engagement may cultivate reflexivity, it remains predicated on individual experience rather than collective or dialogic transformation. Decolonization here appears as a moral encounter with difference, not as a sustained institutional dialogue about epistemic hierarchies.

Across these four examples, IPD1 discourse positions decolonization as a conversion narrative of educators. The teacher becomes both the problem and the solution: the site of illiteracy and its correction. Such discourse reflects an early stage of dialogic engagement, one that focuses on self-examination and moral conviction but seldom opens to collective reflection or institutional dialogue. While this personal dimension is crucial for ethical transformation, its dominance suggests that decolonial reform is still largely imagined through the idiom of individual virtue rather than dialogic inquiry into systemic illiteracy.

2.2.2. IPD2: Cultural Normativity and Discourse

The second cluster of Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD2) encompasses 43 coded passages in which decolonial discourse attempts to persuade universities to adopt new institutional norms, values, and practices. These statements articulate decolonization as a matter of institutional responsibility rather than personal conviction. They seek to reform the moral and cultural infrastructure of higher education by prescribing what universities should become: inclusive, reflexive, and historically accountable. However, while these initiatives express genuine ethical commitment, their form is often prescriptive rather than dialogic, they instruct the institution on how to behave, rather than inviting it to collectively explore the conditions of its illiteracy.

The 43 statements can be grouped into three overlapping normativities that define how institutional change is imagined: (1) accountability and policy reform, (2) curricular and epistemic renewal, and (3) reflexivity and critical awareness as institutional norms.This section briefly discusses each group of normativities.

Reflexivity and Critical Awareness as Institutional Norm

A third normative cluster treats critical self-awareness as an institutional obligation. Reflexivity is no longer a personal virtue but a procedural expectation, to be fostered through training, guidelines, and communicative protocols. Racial literacy is framed as the cultivation of institutional sensitivity, the capacity to name and respond to discrimination through structured reflection.

The rectoral response from Ghent University illustrates this transformation:

“We want to provide space for meaningful conversations about conscious and unconscious discriminatory behaviour such as bullying, intimidation, and micro-aggressions. [...] It is important that we clearly agree, communicate and indicate who should do what when an incident occurs. We need to walk the talk.”

The commitment to “agree, communicate and indicate who should do what” exemplifies the bureaucratization of reflexivity. Listening and self-critique become codified actions, governed by protocols and responsibilities. While this formalization marks an institutional acknowledgment of racial illiteracy, it also risks substituting procedural correctness for dialogic engagement. Reflexivity becomes standardized, an institutional virtue performed through policy.

Across these three normativities, IPD2 discourse reveals how the decolonial agenda seeks to overwrite racial illiteracy through institutionalization. Diversity is operationalized, reflexivity is routinized, and epistemic inclusion becomes a curricular requirement. These interventions are vital steps in addressing structural exclusion, yet they remain framed through an authoritative mode of persuasion. The result is a paradoxical moral governance: the university is asked to decolonize itself through the very bureaucratic mechanisms that have historically sustained exclusion. In this sense, IPD2 represents both the progress and the limitation of institutional engagement, a reformist rhetoric that enacts change through normativity rather than through dialogue.

2.2.3. IPD3: Making Illiteracy Subject to Dialogic Inquiry

The codes grouped under IPD3 centre on listening, questioning, and co-investigating as change-making discourse. These excerpts emphasize inquiry into the institutional conditions of illiteracy itself, foregrounding themes such as accessibility, historical accountability, and epistemic inclusion. Although fewer in number than IPD1 and IPD2, they stand out for their dialogic quality and their potential to transform the decolonial debate from one of advocacy to one of shared exploration. The following section discusses these dialogic strands more thoroughly, tracing how each theme advances a distinct mode of inquiry within the decolonial discourse.

IPD Accessibility to, Well-Being in and Relevance of Higher Education

The first IPD centres on the role of higher education in enhancing accessibility to knowledge, improving student well-being, and increasing the research relevance of higher education. The Decolonize UGent letter suggests initiating a conversation with secondary education to identify the obstacles faced by racialized students in pursuing higher education (code 4). Similarly, the report by VLIR/CREF advocates for investing in audience engagement to learn from and listen to activists (code 1), minorities, and children about how higher education could enhance its accessibility. The report emphasizes that “audience engagement is not only about speaking and teaching but also about listening and adjusting.” Here, the racial illiteracy signifying a lack of representation and awareness about discrimination against racialized minorities is transformed into a dialogic strategy aimed at acknowledging this reality and fostering exchanges to improve accessibility and well-being.

A decolonization of the academic world involves a thorough reflection on the role that universities played in the colonial past. This ought to be based on historical research and should take place in collaboration with colleagues from non-Belgian universities, primarily from the regions involved. However, this reflection cannot be limited to the past, and should also include the contemporary impact of the colonial past (including on educational programs) and visions about the relationship with the former Belgian colonies.

While much of the IPD2 discourse suggests that decolonizing the university can be achieved by implementing an anti-racist cultural normativity, this IPD3 positions decolonization as a learning process that involves dialogue with the distant other. The focus is on engaging academics from non-Belgian universities as the starting point for such conversations.

The VLIR/CREF report compiles an extensive list of initiatives currently being implemented at Belgian universities. While IPD2 discourse advocates for the further implementation of these actions—assuming they effectively contribute to reducing racism—the interuniversity team subjected this list to dialogic inquiry with international experts affiliated with universities in Central Africa and beyond. Although the experts expressed positive surprise at the quantity of actions, they also voiced reservations about the quality and relevance of certain initiatives, noting that similar actions in other contexts did not yield the expected outcomes. As a result, while these actions may initially seem desirable, their desirability may diminish in dialogue with the distant other.

IPD Learning to Reconnect with Central Africa

In this renewed cooperation, the Central African partners must, of course, be listened to first and foremost. It is important to take into account their needs and perspectives, and to realize that they put other problems first.

6 (VLIR/CREF)

The interuniversity report emphasizes the importance of reconnecting with partners and institutions in Central Africa as a crucial element in the decolonization of Belgian higher education. Although Belgian universities were more actively engaged with scholarship on the DRC during the latter half of the 20th century, the report notes that younger academics often feel disconnected, grappling with postcolonial guilt or a reluctance to engage with what they perceive as neocolonial dynamics (ibid. 10). Nevertheless, the report identifies reestablishing connections with Central African universities as essential for revisiting Belgian colonial history from a fresh perspective. Importantly, the report suggests that engaging in dialogue with Central African institutions should include a willingness to reassess and potentially revise our own decolonization goals for higher education.

While a well-balanced curriculum focused on representation politics in Belgium may seem desirable, some consulted experts highlight that issues such as visa and scholarship regulations might be of greater importance to students in Central Africa. Consequently, the report recommends investing in the mobility of Central African students to study at Belgian universities, fostering a deeper understanding of their aspirations, realities, and expectations.

IPD Researching the Contribution of Gendered and Racialized Authors to the Curriculum

Although the students mainly addressed the issue of representation in the curriculum—often advocating for the inclusion of gendered and racialized authors—an intriguing line of thought emerges in an open letter issued by students at KASK School of Arts.

It is certainly true that men are more numerous in the canon because women were simply silenced in the past. It will, therefore, probably require more research to include them, but this is part of the teacher’s task.

7(Student Letter at KASK School of Arts)

Rather than simply assuming that gendered and racialized authors are absent from the curriculum, the letter subtly suggests that these voices may already be present but remain unintelligible because their contributions have not been acknowledged. The students argue that uncovering and recognizing these contributions will require further research. This approach exemplifies Bakhtin’s dialectic thinking where dialogic discourse decentralizes hegemonic claims not by adding a foreign discourse but by interacting with a dimension already embedded within the hegemonic narrative (

Bakhtin 1982, p. 279).

Building on Bakhtin’s thinking, dialogic education does not necessarily disrupt by merely adding or including a foreign discourse; rather, it engages with a dimension concealed by hegemonic discourse, bringing it to light. The students assert that gendered and racialized authors were not absent from history but have been erased from the hegemonic art canon. They further suggest that women have significantly contributed to what we now recognize as the art canon, yet understanding the extent of their contributions—and how the hegemonic canon has silenced them, requires further research (

Bala 2017;

Taylor 2003).

3. Discussion: The Racial Illiteracy Paradox

The analysis of the racial illiteracy identified within the decolonial discourse at Ghent University reveals a complex landscape where different forms of Internally Persuasive Discourse (IPD) interact. The dominant IPD2 discourse, which advocates for adopting new cultural norms and institutional policies, underscores the prevalence of efforts to address the lack of diversity and Eurocentrism in university curricula. However, the predominance of IPD2, along with the more personal belief-oriented IPD1, risks entrenching an anti-dialogic culture that prioritizes surface-level solutions over deeper, reflective engagement. This dominance potentially perpetuates what can be termed an “illiteracy paradox,” where attempts to correct racial illiteracy within a historically racially illiterate institution may inadvertently reproduce the very illiteracy they seek to overcome.

The focus on IPD1 (personal beliefs and attitudes) and IPD2 (cultural normativity) in the decolonial discourse often results in surface-level changes that do not engage with the deeper structural issues at play. For example, increasing diversity sensitivity among professors or implementing quotas for racialized minorities might change the appearance of inclusivity but fail to address the more profound issue of how knowledge is produced and validated within the university. This has implications beyond pedagogy: it mirrors broader processes of racialized citizenship, where recognition is given symbolically through representation while deeper exclusions remain intact.

The dominance of IPD2, which encourages the adoption of new cultural norms without necessarily interrogating the underlying power dynamics, further exacerbates this paradox. By promoting a superficial engagement with decolonial ideas—where representation is seen as an end rather than a means—the university risks perpetuating an anti-dialogic culture. This culture, in turn, stifles the potential for transformative learning, as it frames decolonial efforts as merely a matter of policy rather than a profound rethinking of how knowledge is structured and disseminated. Such surface-level gestures echo how minorities may be granted formal equality as citizens yet continue to experience marginalization, illustrating how racial illiteracy in universities intersects with the lived experience of second-class citizenship.

Interestingly, students’ discourse uses the rhetoric of colonial history in the DRC, without acknowledging the colonial presence still affecting the DRC. On the one hand, students criticize the institution for its lack of knowledge about colonial history, using the DRC as a reference point to emphasize the absence of critical race theory in the curriculum. On the other hand, these same students perpetuate a form of illiteracy by ignoring the current realities and challenges faced by the DRC. In essence, the student-led decolonial discourse reconstructs the history of the DRC while simultaneously silencing contemporary issues. This national focus of the decolonial discourse is incongruent with the transnational nature of colonial history itself and illustrates the risks of imposing representation without fostering the necessary dialogic space for critical inquiry.

To understand the illiteracy paradox fully, it is crucial to recognize that the very institutions attempting to “solve” racial illiteracy are themselves products of a system that has historically marginalized non-Western perspectives. This creates a situation where the tools and frameworks available to address illiteracy are, by their nature, limited by the same biases they seek to overcome. As such, efforts to decolonize education can sometimes reinforce the structures they aim to dismantle, especially when these efforts are not accompanied by a genuine willingness to engage in critical, open-ended dialogue.

The research question this contributed explored is as follows: How does decolonial discourse in Belgian higher education use dialogic and authoritative forms of speech to contest racial illiteracy and unsettle racial hierarchies? The analysis reveals that the discourse operates within a continuum of internally persuasive forms rather than through a single orientation. IPD1 and IPD2 demonstrate that much of the current decolonial debate relies on personal conviction and normative persuasion, whereas IPD3 signals a smaller but crucial movement toward dialogic inquiry. This distribution suggests that decolonial discourse is still negotiating the balance between advocacy and dialogue, between the urgency to act and the patience to listen. It also shows that racial illiteracy is not only the object of critique but a structural condition shaping the very language through which critique is articulated.

Rhetorical Listening and Racial Illiteracy?

Having observed and analyzed the decolonial debate in Belgian higher education, I propose the practice of listening as a project of ongoing inquiry into how knowledge, power, and history intertwine in racial illiteracies and their implications for racial civic engagement and citizenship. Within this framework, the act of listening becomes a pedagogical, ethical, and institutional orientation (

De Clerck and Rutten 2024). It acknowledges that those involved in university education—students, professors, administrators—are themselves shaped by the racial illiteracies they seek to unlearn, and that this process demands not immediate resolution but a sustained attentiveness to partial knowing. Building on

Ratcliffe’s (

2005) conception of rhetorical listening as “standing under” the discourses of others, this approach reframes decolonial work as an opportunity to listen to the cultural logics of when, how and why certain knowledge becomes normative and why, when and how other knowledge does not. It asks not only

what is being said, but

how histories of power shape who can speak, who is heard, and whose knowledge is recognized as legitimate, thus linking acts of academic listening to the broader conditions of racial citizenship and civic literacy.

Powell (

2008), a scholar of Native American rhetoric, advances rhetorical listening toward decolonial storytelling and relational accountability, emphasizing that genuine listening must attend to land, ancestry, and the embodied presence of Indigenous voices. Her work situates listening as an ethical relation grounded in place and community, rather than as an abstract cognitive skill. Similarly,

Inoue (

2015) applies rhetorical listening to the field of writing assessment and race, foregrounding the racial dimensions of linguistic inequality. For Inoue, listening entails institutional accountability: it is a commitment to transforming the standards, evaluative practices, and power relations that sustain racial hierarchies in academic communication, and thereby reimagining the university as a site of racial civic learning and dialogic citizenship.

4. Conclusions

This study examined how decolonial discourse in Belgian higher education uses dialogic and authoritative forms of speech to contest racial illiteracy and unsettle racial hierarchies. Student-led movements and staff-coalitions have emerged as key agents of racial civic engagement, challenging universities as both producers and regulators of racial literacy. Yet these movements and coalitions act within institutions historically shaped by racialized citizenship, where participation and belonging remain uneven. Drawing on Bakhtin’s framework of internally persuasive discourse (IPD), the analysis revealed how decolonial speech oscillates between personal conviction (IPD1), normative persuasion (IPD2), and dialogic inquiry (IPD3). While most initiatives rely on normative and policy-driven strategies, a smaller but significant dialogic strand reimagines the university as a civic space of learning and unlearning.

The findings expose a paradox: in seeking to correct racial illiteracy, institutions and activists often reproduce its discursive forms. Diversity and inclusion policies tend to treat literacy as managerial rather than relational, replacing dialogue with compliance. Rhetorical listening offers an ethical response, an invitation to engage the unfinished colonial question through sustained dialogue, including with partners on the African continent as exemplified by the CRef–VLIR report. Anti-racist civic engagement becomes truly dialogic only when universities listen through decolonization itself, treating illiteracy as a shared inquiry and opportunity to learn rather than a deficit requiring a quick fix.