Abstract

This article highlights the role of adoptee activism in raising awareness and changing policy regarding Intercountry Adoption (ICA) in The Netherlands. Through interviews with a selection of adoptees engaged in activism, this study shows that (i) adoptees became engaged in activism as a result of growing adoptee consciousness in combination with encountering irreconciliation; (ii) they employed many types of activism, sometimes with different goals and strategies; (iii) they cooperated in different constellations and with many allies such as journalists, lawyers and scholars; and (iii) their activism had significant impact on general awareness and government policy. Despite visible progress, reforms have fallen short of their needs, and implementation of government plans remains insecure. Many adoptees therefore feel compelled to continue their activism.

1. Introduction: A Brief History of ICA and Adoptee Activism in The Netherlands

In November 2024, a group of adoptees in The Netherlands—including two of the contributing authors to this article, Sarah and Shila—organised a cultural event on adoption titled VER VAN HIER (FAR FROM HERE).1 This event was created to advance critical debate around intercountry adoption (ICA) through art, culture, and dialogue.2 Performances countered the ‘fairy tale’ narrative of giving children from poor backgrounds and countries ‘a better life’ (Cheney 2014) with the dark sides of ICA, such as the systemic abuses and the challenges adoptees face in terms of loss, identity, belonging, justice, and restoration. All five days of the event were ‘sold out’ (tickets were free), and the visiting adoptees and their allies shared a sense of urgency in this critical debate. Shashitu Rahima Tarirga, one of the participants in the talk show about (in)justice, said:

“All the changes that have come about, even though it is much too little, only happened because critical adoptees have been vocal about everything that is going wrong. Critical adoptees have been vocal for years before me and have done so with heart and soul. And I think that we have the task as the next generations to stand on those critical shoulders of our predecessors. Because if we do not speak out—that is the sad thing about it—no one else will.”

Hübinette (this issue) draws a similar conclusion about adoptees’ roles in coming to terms with ICA in Sweden: they are the most outspoken group when it comes to claiming justice for victims of ICA (Hübinette 2025). Given that The Netherlands has recently placed moratoria on ICA and published plans to permanently phase it out, including enhanced support for adult adoptees, The Netherlands has played a key role in international debates about ICA. Yet little has been written about it in the academic literature. This article therefore details the role of adoptee activism in the changing debates about ICA in The Netherlands. We consider what caused Dutch adoptees to become active in the societal/political debate on ICA and how their actions as an advocacy coalition have influenced the societal/political debate to lead to The Netherlands being among the first countries that is working towards fully and permanently banning ICA. This is especially significant given that The Netherlands is the ‘home’ of the international Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption (1993).3 Ultimately, we argue that adoptee activism was crucial in bringing about the current dismantling of the Dutch ICA system.

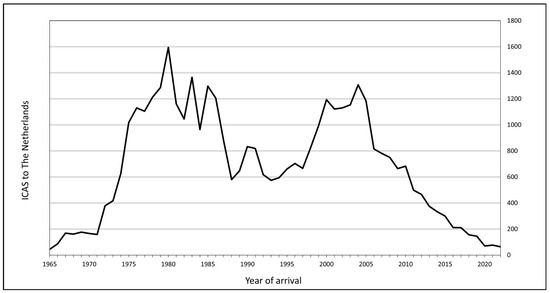

Adoption of children from abroad to The Netherlands began in the 1920s with children displaced by the First World War. This was in fact foster care, because formal/legal adoption was not possible at that time in The Netherlands. In 1956, the Adoption law was introduced to give (foster/prospective) parents more certainty about keeping the child. Under this Adoption law and the Alien Act, Dutch couples adopted hundreds of children from Greece, Austria and Germany in the late 1950s and 60s (Schrover 2023; Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie 2021). ICA in The Netherlands increased in the 1960s and 70s, when thousands of children were adopted from countries such as Indonesia, South Korea, and Colombia—and later also many from China and several European and African countries. The course of adoptions from foreign countries to The Netherlands can be seen in Figure 1. After a steep rise in the 1970s, a decline occurred caused by an economic crisis and growing criticism on ICA (Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie 2021), and again a rise occurred in the late 1990s (with a ‘country record’ of 800 children from China in 2004 (Hoksbergen 2011)). ICAs declined steadily to less than 100 a year in 2020 and 50 in 2023. Altogether, over 44,000 children have been adopted from abroad to The Netherlands.

Figure 1.

The rise and decline of ICAs to The Netherlands. Source: figures until 1971 obtained from (Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie 2021); figures from 1971–2010 obtained from (Hoksbergen 2011); figures from 2011-present obtained from FIOM (www.fiom.nl, accessed on 10 February 2025).

While infertility was initially the main reason people wanted to adopt a child (and has remained an important factor), the narrative surrounding ICA shifted to a neo-colonial language of ‘saving’ children from impoverished countries in the 1970s (Cheney 2014; De Vries et al. 2025; Schrover 2023). However, the Dutch media divulged ICA abuses, scandals, and negative effects alongside these positive narratives of ‘child rescue’ (Schrover 2023). Nevertheless, the dominant narrative that saw ICA as an altruistic act where children were saved from dire conditions in poor families and orphanages prevailed (Hübinette 2004).

Upon reaching adulthood in the 1990s-early 2000s, some of the earliest intercountry adoptees—amongst others from South Korea, Colombia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh—started to gather and form communities. In The Netherlands, this first movement mainly centred on countries of origin. Adoptees from the same country of origin gathered for support, exchanging information, celebrating their heritage, or simply having a good time together.4 Some of these groups also engaged in advocacy and/or assisting adoptees with searching for their origins. While searching for their origins, adoptees found inconsistencies in their own adoption histories. They found that adoption papers were often falsified, and when their parents were found,5 they would often attest to being lied to about—or even robbed of—their children or being forced or pressured to relinquish them.6

Although the Dutch government knew of abuses in ICA from its start in the 1950s, it continued to allow and facilitate these private activities. In 1989 the ‘law on the admission of foreign foster children’ came into effect (renamed in 1998: law on the admission of foreign children for adoption). In 1993, the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption was drafted to increase international cooperation in ICA to prevent abuses (ratified by The Netherlands in 1998).7 Nonetheless, abuses persisted (Loibl 2021; Cheney 2023; Smolin 2024).

In 2016, a critical report by the Raad voor Strafrechtstoepassing en Jeugdbescherming (Advisory Council for the Administration of Criminal Justice and Protection of Juveniles, Raad voor Strafrechtstoepassing en Jeugdbescherming 2016) concluded that, given its inherent flaws and abuses, it would be better to focus on keeping children in families and countries of origin than to perpetuate the ICA system (Raad voor Strafrechtstoepassing en Jeugdbescherming 2016). Despite criticisms from pro-ICA groups (Juffer and van IJzendoorn 2016), the RSJ report prompted a fundamental shift in the discussion on ICA and its ethical implications, challenging the ‘fairy tale narrative’ of ICA. Adoptees and allies increased awareness of the systemic problems in ICA through media, court cases and academic studies, which eventually led to the government-instated Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie (Committee Investigation Intercountry Adoption) who published their 2021 report, commonly known and hereafter referred to as the Joustra Report (Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie 2021), followed by apologies from the Dutch state. According to Smolin (2024), the Joustra Report was “a pivotal point as to recognition of the systemic nature of illegal and unethical practices in ICA”. These events ‘awakened’ even more adoptees to activism, individually or as a group, including adoptees coming of age in recent years such as those from China and Ethiopia.

While adoptee activism contributed to the installation of the Joustra Committee and the conclusions and recommendations were welcomed,8 many adoptees who were engaged in activism felt that the resulting measures taken by the government fell short. For example, critical adoptees were disappointed because the Dutch government imposed a moratorium on ICAs in 2021 (to ‘protect children from abuses’), that did not apply to adoption procedures that were already initiated and that was lifted a year later. Also, the government budget allocated to compensate those who suffered adoption abuses was spent largely on an ‘expertise centre’ that has not responded to adoptees’ needs as stated by adoptees who were consulted.9 Furthermore, when Parliament urged the government to phase out the ICA system in 2024, the resulting plan still allowed 600 children to be adopted over the course of 6 years, without significant guarantees that additional abuses would not occur.10 In short, government policy still used the same tactics mentioned in the Joustra report—dismissing/minimising signs of abuses, prioritising the wishes of Dutch adoptive parents, and the idea that ‘saving children’ through adoption justified the risk of irregularities in adoptions—to argue for continuation of ICA. These developments therefore provided ample reasons for adoptee activists to continue advocating for their rights.

2. Theory and Methods: Adoptee Consciousness, Advocacy Coalitions, and Irreconciliation

To explore how Dutch adoptees got engaged in activism, we draw on Branco et al.’s (2023) adoptee consciousness model (ACM). This model comes out of Freire’s social activism literature on critical consciousness and describes the process by which marginalised people…

“…develop awareness, or consciousness, of the institutional and societal structures that maintain their oppression, and engage in activism to dismantle the status quo… critical consciousness emerges with problem identification, continues with the deep reflection that initiates motivation for change, and ultimately brings forth transformation and liberation”.(Branco et al. 2023, p. 54; see also Freire 1970; Chovanec and Lange 2007)

Branco et al. (2023) build upon critical consciousness by applying it to adoptee consciousness in the ACM. The ACM helps further explicate adoptees’ motivations for activism specifically, as it unpacks what adoptees often call ‘coming out of the fog’. This refers to the emerging awareness of the impact of adoption and its problematic, systemic aspects (Branco et al. 2023). Branco et al. (2023) explain how adoptees can reach different touchstones in their lives that move them away from the first touchstone, the ‘status quo’ (the earlier mentioned dominant fairytale narrative) by, for example, finding out that their adoptions were unethical or illegal, or when they encounter racism within or outside the adoptive family (touchstone ‘rupture’). Such a rupture can lead to the touchstone ‘dissonance’ as one deals with the tension between past beliefs and new (opposing) information. Working through that period of dissonance can lead to the touchstone ‘expansiveness’ when adoptees can see/embrace/tolerate the various paradoxes adoption entails. The model’s final touchstone, ‘agency’, is comprised of activism and forgiveness (Kim et al. 2025). However, Branco et al. (2023, p. 57) note that “Individuals can and often do move between these touchstones in non-linear ways… Most adoptees do not settle in and remain in just one period of consciousness through their lives.”

For this article, we are interested in activism rather than forgiveness, as the underlying causes for activism are forms of continued injustice—a state of ‘irreconciliation’ that is connected to (or leading to) activism, whereas forgiveness refers to a state of acceptance and resignation. This approach highlights the unresolved issues that continue to require attention, rather than prematurely emphasising reconciliation when substantial barriers remain (Smolin 2024; De Vries et al. forthcoming). According to Mookherjee (2022, p. 174):

“[irreconciliation] occurs when past historical injustices have not been addressed in spite of the issues having been raised; when historical injustices have been symbolically addressed through committees and investigations only to strengthen the status quo and resist the truth; and when the protests continue against such virtue-signaled and performative redress.”

This is precisely what Dutch adult adoptees are faced with, according to Withaeckx (2024, p. 275): “adult adoptees’ emotional pleas for reparations, care and support are met with cold rejections” by governments and adoptive parents alike. The concept of irreconciliation therefore helps to explain how adoptees arrive at the agency-activism touchstone.

We consider activism to consist of such activities as raising awareness, changing the narrative, seeking justice, and influencing politics. In light of the events described in the introduction, we consider abuses in the adoption system to entail not only what preceded the adoption, e.g., coercion of first parents, stealing of children, or fraudulent adoption papers (often referred to as illicit/illegal/unethical adoptions and considered child rights violations) and how this affected the lives of adoptees and their progeny, but also the lack of support for (adult) adoptees in searching for their roots and the restoration of their original identities, the loss of connection with unsupportive adoptive family members as well as other adoption system actors who denigrate adoptee activists in pursuit of maintaining the status quo and the continuation of adoption policy with inadequate measures to prevent the abuses.11 Adoptees‘ strategies and goals in these debates may differ, but as deliberate action aimed at societal change, it can be seen as ‘activism’ (Anderson and Herr 2007), even though not all critical adoptees would use the term for themselves.

We furthermore expect that considering adoptee activism in the context of an advocacy coalition helps to examine how and to what extent they influence ICA policy. An advocacy coalition comprises organisations/individuals who can belong to different groups, sharing specific core principles. They “share a set of normative and causal beliefs and engage in coordinated activity over time” (Koch and Burlyuk 2020, p. 1444). The coalition that has been challenging the dominant, positive narratives regarding ICA in The Netherlands is composed of adoptees, journalists, critical scholars and NGOs, amongst others. On the other hand, a pro-ICA advocacy coalition comprising adoption agencies, (prospective) adoptive parents (associations) and Dutch scholars, has been active since the 1970s, promoting ICA and defending its ‘good name’ (De Vries et al. forthcoming). A group of adoptees has joined this coalition in the past decade (Stichting Interlandelijk Geadopteerden (SIG)), who may be seen as defending the status quo touchstone of the ACM. Both the pro-adoption and the critical adoption coalitions have been active in influencing ICA debates in The Netherlands.

In this article, we focus on the coalition that is critical of Dutch ICA policy and practice, advocating for ICA abolition, children’s rights, and/or support for adult adoptees. Recent adoption scholarship discusses various remedies, reparations and reforms (e.g., Gesteira et al. 2021; Blake et al. 2023; Cawayu and Sacré 2024; Loibl and Smolin 2024), as well as ICA abolition (Cawayu 2023; Cho et al. 2025). The literature raises the political debate in The Netherlands as salient example of shifting debates, acknowledging the role of adult adoptees (Loibl and Smolin 2024). However, academic literature about this Dutch adoptee advocacy coalition and how it was involved in the changing policy/political debate in The Netherlands is lacking.

This article is therefore a first comprehensive attempt to document the activism of adult adoptees as actors within the ICA system in The Netherlands. We contend that going through the steps of ‘adoptee consciousness’ and encountering ‘irreconciliation’ are important drivers for critical adoptee activism. With these two guiding principles (adoptee consciousness and irreconciliation), we aim to better understand adoptee activism and how it has influenced Dutch ICA debates. The three main questions of this study are:

- How have the adoptees’ life trajectories led to activism, and can their activism be explained by the adoptee ACM and/or the irreconciliation model?

- What types of activism do adoptees engage in, what are their aims, strategies, and how do they cooperate?

- What is the impact of adoptee activism on the adoptee community, broader society, and politics?

We selected a purposive sample of adoptee respondents who have been particularly influential in Dutch ICA debates. We selected a diverse group of adoptees (in age, gender, and country of origin) who became active in different periods. The authors’ in-depth knowledge of the Dutch adoption community allowed us to reconstruct adoptees’ activities and contributions during key moments in the movement. Because all respondents are well-known in the (social) media, they agreed that we use their actual names. Table 1 shows a list of the respondents.

Table 1.

Respondents’ personal information.

We interviewed each respondent in Dutch for approximately 2 h in Spring/Summer 2025. They received the main questions about their involvement in activism (Appendix A) beforehand so they could prepare and reflect, allowing them to bring up additional issues. The authors had sub-questions at hand to make sure that the touchstones of adoptee consciousness were addressed, and that their activism could be related to key moments in the ICA debate in The Netherlands. A timeline of these key moments is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Timeline of key moments.

We translated the Dutch transcription into English using a combination of AI and manual transcription for improved accuracy. We analysed the transcripts thematically to reveal the patterns and themes detailed below. The respondents’ information is also complemented with our auto-ethnography and participant observation—including at the FAR FROM HERE event—to fill any gaps in the narrative. Two of the authors, Shila and Sarah, are part of the adoptee activist community. Sarah has been engaged as children’s rights expert since 2021 and Shila was active since 2017, the first couple of years with the adoptee organisation from Bangladesh, and since 2022 as critical adoption scholar. The third author, Kristen, is a critical adoption scholar who was based in The Netherlands from 2010 to 2022 and has contributed as a scholar and children’s rights advocate to critical adoption studies, as well as to the political debate in The Netherlands; her work was cited in the RSJ report, and she was interviewed by the Joustra Committee. We therefore position ourselves as critical adoption scholar-activists.

In the following four sections, we first describe the growing consciousness of adoptees (Section 3). Secondly, we discuss the different kinds of activism they were engaged in and the goals and strategies used (Section 4), followed by the way in which they formed coalitions (Section 5). Finally, we discuss the impact of adoptee activism (Section 6), before rounding off with our conclusions (Section 7).

3. Results: Growing Adoptee Consciousness

The respondents combined elements of ‘rupture’ and ‘dissonance’ in their descriptions of the departure from the status quo (Branco et al. 2023). The occurrences that respondents said caused ‘rupture’ varied. Patrick talked about fellow students in college: “a Belgian, who just returned from a yearlong exchange, learned the language and experienced the culture of Brazil. He knew an incredible amount about it—that felt painful and unfair.” And when Patrick wanted to recover/reclaim his original language by taking a language course, his adoptive parents did not support him. Most of the respondents first encountered adoption abuses individually (the ‘rupture’), thinking that inconsistencies and mistakes in their adoption stories and files were incidental. Only after hearing other adoptees’ stories (personally, through adoptee organizations, or via the media) did respondents realize that abuses are systemic, causing a ‘dissonance’ in their belief systems. For some of the respondents, such information came through adopted friends; for others, it was a 2017 nationally broadcast documentary series Adoptiebedrog (Adoption Fraud by Zembla),12 or the publication of the Joustra Report in 2021. We contend that realising this systemic nature of abuses in the ICA system constitutes ‘expansiveness’ and is an important step to arrive at the agency-activism touchstone of the ACM as it constitutes recognition of ‘the institutional and societal structures that maintain their oppression’ (Branco et al. 2023).

The respondents have been active in different periods. Hilbrand, Dewi, and Patrick are amongst the ‘trailblazers’—so logically their discoveries came from (more) personal experiences. The respondents that started their activism later (Dilani, Dong Hee, and Qian), all attest to overcoming their dissonance and achieving expansiveness (Branco et al. 2023) by learning from and being inspired by those who preceded them: they learned about the systemic aspects of abuses through the aforementioned media/reports that their predecessors played a role in (the activities of the respondents are discussed in the next section).

The Joustra Report provides a good example of how adoptees contributed to other adoptees’ growing critical consciousness (expansiveness). From 2017–2018, the Ministry of Justice and Security, responsible for adoptions, received 14 formal information requests from individual adoptees and adoptee organisations because of abused they uncovered in either their personal adoption histories or more generally in adoptions from their countries of origin. Patrick was one of them, and in dealing with his case, the Ministry found that one or more people connected to the Dutch government were involved in illegal adoptions from Brazil. That is why the Joustra Committee was installed. Many adoptees involved in activism were interviewed, as well as other experts such as Kristen, who pointed out to the Committee’s surprise that ‘wrongdoing’ in ICA was not ‘in the past’, as they had framed it, but that it was still happening.

The Joustra Report was national news, and it reached many adoptees who until then had little knowledge of (the systemic nature of) adoption abuses. Dong Hee already had doubts about her adoption story (rupture), but the Joustra Report was a tipping point for her to engage in activism. She recognised her own story in what it said about abuses (dissonance), so she started to look for others on social media and dove deeper into the matter (expansiveness). Qian, on the other hand, had just started working on her documentary in 2021. She learned a lot from interviewing adoptees like Patrick: “gradually you see me, literally in front of the camera, you see me falling out of the fog.”

While the process of ‘rupture’ from the status quo differs for each respondent, it generally occurs outside the adoptive family. Even though some respondents experienced racism within their families while growing up, they were not always able to label it as such, being in their white adoptive families and not knowing (enough) what racism and micro-aggression entails. Many respondents attest to a troubled or broken relationship with their adoptive parents once they engaged in activism. Hilbrand described this dissonance as an integral part of adoptee activism which, according to him, is a complex chess game: “[critical adoptees] should be prepared to antagonise people around them, including adoptive parents, partners, and employers”. The influence of adoptive parents can be outspoken or more subtle. An example of the latter is given by Qian, who recalls her first trip back to China at the age of 14 when her adoptive mother, while boarding the airplane, squeezed her hand and said, ‘do stay ours’. “That holiday made me feel even more Dutch, pushed deeper into the fog,” Qian said, demonstrating the non-linearity of the ACM. A notable exception was Dewi’s adoptive mother (who passed away in 2022). She was the only adoptive parent who publicly engaged in activism together with any of our respondents, facilitating Dewi’s sense of agency.

Many of the respondents started to engage in activism as a result of their personal process of going through the ACM touchstones: discovering their original identity and the impact adoption had on them, experiences with lacking information, and/or encountering injustices associated with that process, including prohibited access to information about one’s origins, discovering fraudulent adoption papers and procedures, and finding out family was coerced or misled, are all examples of dissonance that they have had to deal with. While Hilbrand pointed out that this developmental process of adoptees can sometimes lead to ambivalent behaviour, making cooperation difficult, the fact that (hardly) anybody was doing anything to overcome the injustices respondents were faced with, and finding resistance from actors in the adoption system (expansiveness), galvanised the respondents’ urge to strive for change (agency-activism). Because this lack of solutions and active resistance continue to date, respondents feel an irreconciliation that compels them to continue their activism.

4. Results: Adoptee Activism

4.1. Different Types of Activism

Most respondents started with research, because they found that knowledge about adoptions from their countries of origin, the adoption process in The Netherlands, and/or the impact of adoption was lacking. After publishing their findings, either in op-eds, social media, websites, books, podcasts or documentaries, they were interviewed by national media outlets such as talk shows, newspapers, and documentaries—both in The Netherlands and abroad. Several respondents mentioned getting and staying in touch with journalists as a strategy. By repeatedly publishing aout adoption from the adoptee perspective, some of these journalists can be considered allies. Qian is a journalist herself, who got the double traction of being both an adoptee and a journalist. Her documentary series De Afhaalchinees (the Chinese Take-away) aired on national television and generated a lot of media attention, including being nominated for several awards.13 This attests to the impact of cultural/artistic expressions.

Some of the respondents resorted to court cases to address the injustices faced in their adoptions. Patrick and Dilani appeared regularly in the media because of their unique legal battles against the State, adoption agencies, and/or adoptive parents.14 Their cases were connected to ongoing discussions about adoption policy, and they both aim(ed) for a broader impact: “I just wanted to know who I am, where I come from,” says Patrick, who founded an NGO centered around the human right to identity.15 “And the moment I notice something is not right, I can’t close my eyes to it.”

Art is also a form of activism, and FAR FROM HERE is a recent example in The Netherlands. Adoptee artists expressed both their personal stories and systemic aspects of adoption through visual art, music, dance, and spoken-word performances. Such events contribute to adoptee agency and public awareness. Dilani, a professional photographer, also made use of her art to show to the judge during the COVID-19 pandemic, when public attendance was prohibited, that she was not alone in her demands. Her photo series Pink Cloud Project, depicting adoptees with a baby photo or critical statement was submitted as supporting documentation in the court hearing. Dilani continued engaging others in her activism through Pink Cloud Project with a podcast series, to increase critical awareness about adoption.

Despite court rulings in favour of Patrick and Dilani, the government persisted in appealing these decisions. The State’s persistence not only reinforced their determination to continue their legal struggle, but also prompted members of Parliament and NGO’s to publicly advocate on their behalf.16 Dewi, who is a lawyer, held the state liable for insufficient action to prevent child trafficking and sought financial compensation for those who search for their families.17 Dewi explains, “The liability claim was also meant to attract attention, to open the political debate via that route.”

The respondents who initiated contact with Members of Parliament said that it was difficult to find parties willing to advocate for adoptee rights and for a more critical perspective on ICA policy. Some political parties turned out to represent and even include adoptive parents whose interests are better served by keeping the adoption fairy tale narrative alive. MP Michiel Van Nispen of the Socialistische Partij (Socialist Party) was especially responsive and consistently represented critical adoptees’ interests in Parliament. Because several respondents, along with many others, had regular contact with him, he filed numerous questions and motions in Parliament representing critical adoptees’ concerns. According to Hilbrand, Van Nispen was responsible for adoptees formally becoming part of political discussion on ICA. In 2017, together with an adoptee who represented a pro-adoption SIG, Hilbrand was invited to speak at a Parliamentary roundtable hearing discussing the RSJ report.18

Lobbying also took place directly at the Ministry of Justice and Security. While Hilbrand reported that in the 1990s, Ministry employees told him to be grateful instead of complaining, other respondents who later engaged with the Ministry felt they were at least heard, if not heeded. Dilani recounts her meeting with (then) Minister Weerwind, who wanted to talk with her ‘face to face’ but who still continued with the State’s appeal to the Supreme Court against her, making her think “You are talking shit”, reflecting a shared sentiment about the Ministry’s intentions amongst most respondents. Dong Hee currently takes part in reflection sessions with the Ministry of Justice, and though she deems it important, she considers the impact of such sessions limited. Sarah initiated several lobby statements, together with and/or co-signed by many (adoptee) scholars and other experts, child rights NGOs, and adoptee advocacy groups. She was also invited several times to discuss the ICA system with the Ministry as an expert on children’s rights. In her experience, she was listened to and taken seriously, but she also felt invited just to check the ‘critical parties consulted’ box because the Minister did not change the policy at that time in a way that addressed the concerns.

While some of the respondents performed their activism individually, others joined or founded organisations to represent adoptee interests. Many respondents either founded an NGO, or were active in one, to address structural issues.19 Hilbrand, for example, co-founded United Adoptees International (UAI) in 2006, partly because the Ministry of Justice wanted a single point of contact rather than different country-oriented adoptee organisations.20

Others contribute to activism goals through their professional skills. For example, Hilbrand is an experienced counsellor dedicated to adoptee mental health by coaching and systemic documentation of adoptee trauma, which helps adoptees navigate the touchstones of adoptee consciousness and contributes to adoptee agency (and potentially activism). There are also adoptees in academia who have become critical scholars of adoption and dedicate their research to addressing social justice in ICA (see several contributions to this issue). Shila is one of them in The Netherlands, and the number of critical adoptee scholars is growing in Europe and other parts of the world.

4.2. Goals and Strategies

The goals that the respondents pursue with their activism include: finding the truth about their adoptions (on individual and systemic levels); recognition of the right to identity and access to origins; justice for the victims of ICA; protection of children’s rights; support in the search for identity (restoration); adoptee mental health; and raising awareness about the negative impacts of adoption. Respondents strive to be heard and contribute to a narrative about ICA beyond the status quo of the adoption fairytale, dominated by adoptive parents. While all respondents thought that ICA abuses can only be prevented when the ICA is abolished, abolition was not an explicit goal for everyone in their activism. Several respondents relayed that not openly expressing an anti-adoption stance helps one get invited to political and media tables, and to gain support for adoptees. Qian said: “as soon as you start saying ‘adoption sucks, it should stop’, then no one listens anymore.” Dong Hee has been a strong advocate for ending further injustices as part of restorative justice, and she has advocated for ending ICA. To this end, many adoptee organisations, individual adoptees, and allies (including all respondents and authors of this article) have issued or signed statements supporting a permanent end to ICA in The Netherlands.21

Another difference in approaches between respondents is the use of personal stories. Some of the respondents chose not to talk about their own experiences, preferring to focus on the systemic aspects. However, some of the respondents make explicit use of their personal stories and tie them in with the broader narrative, like Dong Hee—even though she also has experience with media zooming in too much on the personal narrative at the expense of the larger narrative. Qian deliberately uses personal stories in her documentary series to gain attention—but always to illustrate a systemic pattern. Yet others allow their stories to be utilised by critical adoption scholars.

5. Results: Advocacy Coalition Building

5.1. Cooperation Among Adoptees

Cooperation between adoptees has not always been easy, which might be partly due to the different goals and strategies. When adoptees began to engage in activism in the 1990s and 2000s, the structural aspects of ICA abuses were not yet fully visible, and a common cause had not yet been formulated. Respondents like Patrick and Hilbrand therefore felt that they had to do it all on their own. Dong Hee also noted that some adoptees within the Korean adoptee community did not want to hear about abuses and the complexity of the system; they just wanted to have a good time together. Dewi, who cooperated with several organisations, felt like she was the one pulling the cart and when she stopped, none of them took over. She acknowledges that other adoptees did eventually continue, albeit a bit later, and that a discernible pattern of advocacy coalition building emerged. Adoptees have learned from each other through the news media and social media networks, and they build upon each other’s work. Individual adoptees and organisations generally knew about each other’s work and collaborated in different constellations.

Hilbrand tried to set up several ‘umbrella organisations’ for political impact. Since the Ministry of Justice had explicitly asked for one point of contact, Hilbrand tried to realise this with UAI, which was a strong public voice in the late 2010s. Several other sub-coalitions formed, such as the one Dewi was involved in, with adoptee representative organisations from Indonesia, Bangladesh and Colombia. Dong Hee mentioned regular interaction with adoptees in WhatsApp groups, and Qian not only interviewed adoptees for their personal stories but also involved many adoptees as experts in her documentary. The aforementioned lobby statements by human rights NGOs are a testimony to the success of coalition building as is a letter to the Dutch Parliament committee responsible for adoption written by Dong Hee together with another adoptee and two anti-discrimination organisations. The letter, containing 62 signatures, asked for reparations and justice for adoptees. Again, they build upon earlier activism: in 2017, UAI sent a similar letter to Parliament signed by 21 organisations and individuals.22

The organising team of the above-mentioned cultural event FAR FROM HERE consisted of a couple of adoptees working in the arts sector, an adoptee scholar, an adoptee children’s rights expert, and representatives of adoptee organisations. Another successful cooperation is the Dutch-language book titled Voorbij Transnationale Adoptie: Een Kritische en Meerstemmige Dialoog (Beyond Transnational Adoption: A Critical and Pluri-Vocal Dialogue) containing 27 contributions in the form of personal reflections, essays, and academic articles—over 60% of which are (co-)authored by critical adoptees. Many of the respondents also interacted with adoptees in other countries of destination, to learn from each other’s experiences.

5.2. Gaining Allies

Some of the examples in the previous section (e.g., the lobby letters and the book) involved individuals and organisations without an adoption background and who can be considered allies. Among them are critical adoption scholars like Kristen and human rights organisations. Some respondents specifically mentioned Defence for Children (DCI), International Child Development Initiatives (ICDI), and Comensha. Respondents also expressed that some journalists and documentary filmmakers proved to be important allies in bringing their stories to the broader public. Both Patrick and Dilani were represented by human rights lawyers who also made more general statements in the media about adoptee rights. The Nederlands Juristen Comité voor de Mensenrechten (Dutch Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights) proved to be a key ally for Dewi, publishing in national newspapers and writing lobby letters together.

Adoptees also paired up with other social movements. Dong Hee actively co-operates with Verleden in Zicht (Past in Sight), an organisation representing domestic adoptees in The Netherlands, another organisation representing donor-conceived children, and Asian Raisins, an anti-Asian-racism organisation. The broadcast company Zwart (Black) supported Qian to explore her identity and make the documentary series, but it also supported the broader adoptee community through the appearance of many adoptee experts in the second season of The Chinese Take-away and by publishing additional in-depth interviews with four of them on their website.23

5.3. Confronting Adversaries

Respondents also talk about people they interacted with who proved to be uncooperative or even countered adoptee activism. The above-mentioned pro-adoption adoptee group SIG and organisations of adoptive parents and adoption agencies also expressed counter-narratives in the media (De Vries et al. forthcoming). Moreover, adoptive parents exercise influence in different organisations such as the Parliament, editorial teams of news outlets, and academia. Hilbrand noted that, especially in the earlier years of adoptee activism, it took a lot of effort to counterbalance the dominant voices of adoptive parents. Today we still observe that adoptive parents’ organisations attempt to minimise the voice of critical adoptees by framing them as a small group of adoptees with traumas related to wrongdoings in the past.24

Lobbying with Parliament and the Ministry of Justice and Security, as mentioned in Section 4.1, resulted in a ‘mixed bag’ when it comes to gaining allies or adversaries, but employees and ministers of the Ministry of Justice and Security, responsible for adoptions, are generally considered less of an ally and more of an adversary by the respondents. According to Patrick, employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs also initially showed empathy but ended up actively barricading doors, for example, by not sharing information relevant to Patrick in the search for his identity. Patrick acknowledges the rationale of balancing interests in decision-making, yet he perceives the resulting outcome as inequitable. Moreover, the turnover of employees and ministers alike has considerable consequences: Dewi says she dealt with two different ministers and felt she had to start over again each time to show them her point of view. She decided to quit her activism in 2024 upon hearing that the ruling government coalition collapsed, because she did not want to start all over again. While the authors held the interviews for this article, the ruling government coalition collapsed again in June 2025. New elections at the end of 2025 will lead to yet more new members of Parliament and responsible Ministers. It remains to be seen whether new allies or adversaries will emerge.

6. Results: Adoptee Activism’s Impact

6.1. Impact on Popular Debates

Respondents agree they made an impact by creating awareness amongst the adoptee community—a valuable outcome of their activism. Dewi said, “For many adoptees, it is important that the Joustra Report confirmed what is going on and that there is recognition. That was enough for a lot of them.” Patrick stated that “Adoptees are finally informed. [They] dare to speak out, that is a breakthrough. A network has been built, also internationally, but it still depends on people”.25 Dong Hee says about the impact of her work that “It is satisfying. I see that I set things in motion. That I help others”. Patrick mentioned that the positive atmosphere at the launch of Qian’s second season of The Chinese Take-away, especially for adoptees, was evidence of the growing adoptee community in The Netherlands. Sarah and Shila have experienced the same atmosphere of solidarity at FAR FROM HERE and other community events.26

Some of the respondents also interacted with adoptees in other countries of destination, mainly in Europe, to learn from one another’s experiences. For example, Dewi connected with other adoptees from Indonesia in Germany and Scandinavia, and Dilani was contacted by several people from abroad who were interested in her approach, and she has been in touch with a group of Swiss adoptees from Sri Lanka to exchange information. She wishes such networks would grow to become worldwide networks.

Respondents’ opinions differ regarding their impact on the broader society in terms of changing the narrative of adoption. The Dutch news media’s growing attention to the subject of ICA from the perspective of adoptees is an indicator of more general/public awareness. Dewi said, “We really opened the social debate. Social media also plays a part, which was much less [prevalent] ten years ago.” One of the FAR FROM HERE attendees, Shila’s PhD supervisor and a development studies scholar Dirk-Jan Koch, described the impact of art performances:

“It really struck me. Of course, I knew about the disadvantages of adoption, but when you hear and see music and dance performances about missing your first family and culture, it really comes to life”.

Nonetheless, respondents indicate that they still struggle to be heard, especially regarding the systemic abuses of ICA, instead of only the personal/anecdotal. Hilbrand, while pointing towards the interviewers and himself, said, “I think we are in a bubble. If you hit the streets and ask people what they think about adoption, you find that hardly anything has changed.”

6.2. Impact on Political Debates and Adoption Policy

As for the impact of adoptee activism on the Dutch political debate on ICA, the most salient evidence is the installment of the 2019 Joustra Committee, the apologies by the Dutch government after publication of the Joustra Report, and—after going back and forth—the 2024 government’s decision to phase out ICA in The Netherlands. The conclusions and recommendations of the Committee were in line with what adoptees had been addressing with their activism for years. The report confirmed that their stories were not isolated incidents but a pattern of systemic abuse. Still, some respondents felt that a Parliamentary inquiry where people have to speak under oath would have yielded better results. Other visible results are that Ministers and Parliamentarians explicitly mention the influence of adoptees on their decisions and motions.27

Respondents also felt that the government’s actions following the February 2021 apologies fell short, in part because the initial moratorium on ICA was lifted, and the government (through appointed commercial advisory bureaus) repeatedly inventoried adoptees’ needs, without properly addressing them. According to Hilbrand, these advisors stated they did not use existing knowledge such as input given earlier by adoptees, because they wanted an ‘objective approach’. Most of the respondents find that the Expertisecentrum Interlandelijke Adoptie (Intercountry Adoption Expertise Centre (INEA)), established to meet adoptees’ needs, does not deliver on the promises made by the government. Dong Hee said she tried to cooperate with INEA at first, but she felt rejected and humiliated when addressing critical issues in a group of adoptees. Dewi says, “there was a subsidy scheme for group roots travels where you would travel to a country [of origin] to taste the culture,” which does little to support her main goal of finding the truth about adoptions. Overall, the main criticism from the respondents is that INEA lacks independence from the government, and that individual (financial or other) support for adoptees is still absent. In that regard, oppressive systems prevail, despite formal investigations, apologies, and adjustments to the system, indicating an irreconcilable state.

Cautious optimism prevails amongst the respondents regarding the 2024 plan to phase out ICAs to The Netherlands by 2030,28 after Parliament voted in favour of Van Nispen’s motion to that end.29 Dong Hee said “we explained to him on numerous occasions that a precondition for restoration is that the injustices stop, that we stop creating new situations of injustice.” Patrick is of the opinion that political will to uncover and acknowledge the darker truths about ICA is lacking: “We may be one step ahead, but with exactly the same structural problems.” Regarding the plan to phase out ICA, Hilbrand does not believe it until he sees it, mainly because of the many actors who are in favor of maintaining the status quo. Dong Hee considers the period in which she is operating currently as an advantage, because progress is visible.

6.3. Personal Impact

Respondents note that activism requires a lot of time and energy. Despite the visible progress discussed in the previous section and the respondents’ strong feelings of responsibility and solidarity in the face of social injustice that cause adoptees to remain engaged in activism, all respondents also attest to the personal toll, leaving them exhausted. Some respondents have received insulting and discriminating comments from strangers online, and some respondents attest to being insulted and threatened by adoptive parents.30 Adoptees may temporarily or permanently withdraw from activism as a result of its impact on their mental health. Indeed, burnout is common amongst social justice activists (Chen and Gorski 2015). Contributing factors include the stress associated with sustained activism and the experience of frustration and ‘fatigue’ when significant efforts yield limited measurable outcomes, persistent resistance from actors in the field, and insufficient support within the adoptee community itself.

Some of the respondents are withdrawing from activism, but they all remain committed to adoptee justice and wellbeing in some form. At each new step in the legal process, Dilani reconsiders whether to quit or move on, because of the energy it takes. But she continues, basically “because it’s unfair” and “it kind of feels like a duty to continue.” Despite the toll, respondents spoke of the personal gains of their activism, such as the feeling of autonomy, ownership over one’s own story, and solidarity amongst adoptees. As Dong Hee said, “I determine my own narrative. And that gives me strength.”

7. Conclusions: Adult Adoptees as Vested Actors in ICA Debates

This study contributes to the academic literature by giving in-depth insight into the role of adult adoptees in ICA debates in The Netherlands. It suggests that adult adoptees are a growing and influential voice in the debate. While adoptees who were active in the 1990s felt like they were fighting an uphill battle, today, adoptees see the impact of their activism, acknowledging that the current successes (e.g., in media and politics) could not have happened without their predecessors’ ground-breaking work.

This article documents how adoptee activism contributed to a shift in the popular perception of ICA and to bringing about the changes in ICA practice and policy in The Netherlands. The study sheds light on critical adoptee consciousness in general by applying the ACM and, more specifically, provides a first account of the role of adult adoptees and their advocacy coalition in the ICA debate in The Netherlands. Therewith, it provides a basis for further research exploring these topics—for example, by investigating other advocacy coalitions active in ICA debates, or by engaging with adoptee activism across different contexts.

Adoptees engaged in activism went through every touchstone of the ACM in various ways. Although adoptee consciousness follows similar paths to other social consciousness models, adoptees face the added complication that their adoptive parents, as well as other vested actors in the ICA system, can consciously or unconsciously reinforce the status quo. This can block adoptees’ path towards agency. We can see that effect in (un)subtle remarks by adoptive parents and in political decision making.

A common and important development leading adoptees towards activism is that at some point they found out that irregularities in their own and/or other people’s adoption stories are not incidental but systemic, which motivated them to strive for change (Freire 1970; Branco et al. 2023; Kim et al. 2025). Although change is gradually occurring, the desired transformation (ICA abolition, children’s rights, and/or support for adult adoptees) has yet to be fully achieved. Hence, while the ACM explains how adoptees come ‘out of the fog’, expand their knowledge about the ICA system, and take agency to change it, the concept of irreconciliation (Mookherjee 2022) helps us understand why adoptees feel compelled to be engaged in and continue their activism. The adoptees interviewed acknowledge and celebrate that progress has been made towards greater recognition of the impact of adoption and abuses, enhanced support for adult adoptees and/or abolition of ICA in The Netherlands. Still, they feel compelled to continue because the measures fall short of their needs—despite critical research reports and apologies by the state.

How adoptees operate as agents in the popular and political debate on ICA are diverse and varied in The Netherlands and elsewhere. A common aim is to change the fairytale narrative of ICA that maintains the status quo (Branco et al. 2023), working towards recognition of the darker sides of adoption, including identity issues and systemic abuses, support, and preventing future child rights violations by ending ICA altogether. Activists worked individually but also often as a coalition. There are formalised organisations that represent a broad group of adoptees, foundations related to countries of origin, as well as many informal cooperative projects such as FAR FROM HERE, the edited book Beyond Transnational Adoption, and the joint lobby statements. Besides the activities mentioned in this article, many other adoptees are active in The Netherlands in different categories, such as the arts (e.g., theatre, documentaries), media such as podcasts, and adoptee mental health. Adoptees also expressed that it can be difficult to cooperate with one another. Reasons can be that their goals are not aligned or that preferred strategies differ. Sometimes adoptees simply follow their own strengths, resulting in different choices such as legal paths, artistic expressions, or lobbying.

Many allies are part of the critical adoptee advocacy coalition, and journalists, lawyers, child rights organizations and scholars have made especially important contributions. Without the platforms they provide, and the multiplier effect of their advocacy efforts, the adoptee advocacy coalition probably would not have been so successful. However, adoptees also experienced the resistance of pro-adoption actors. This group generated the ‘adoption fairy tale’ narrative in the first place, and they try to keep it alive, sometimes by minimizing the dark side of adoption and negative adoptee experiences, and even by actively insulting or threatening critical adoptees. Moreover, ICA has become an ‘industry’ in which substantial amounts of money and emotion are invested in the name of ‘child rescue’—and lucrative schemes are not easily dismantled (Cheney 2014; Withaeckx 2024). Adopters also try to frame critical adoptees as a small (dissatisfied, traumatized) group, while the various joint efforts of the critical adoptee coalition points towards a significant, growing group of critical adoptees.

Especially since the last decade, awareness of the darker sides of ICA grew as a result of media portraying more and more adoptees’ stories, highlighting their individual experiences as well as systemic abuses. Additionally, adoptees’ political lobbying and court cases (Patrick’s in particular) culminated in the instalment of the Joustra Committee. The publication of the Joustra Report in February 2021 was a huge accelerator in both awareness of the systemic nature of ICA abuses and shifting government policy. While the ICA moratorium of 2021 was quickly lifted and real change seemed elusive at first, the Joustra Report led to many new critical adoptee coalitions, and their combined efforts contributed to the 2024 Parliament vote to gradually phase out ICAs to The Netherlands and to improve support for adoptees. The Joustra Report also inspired other countries in Europe such as France, Switzerland, Norway and Sweden to conduct their own investigations into ICA, and in various countries adoptee activism also played a role in changing policy (Blake et al. 2023; Kruijsse-Brugge 2024; Hübinette 2025). The Dutch government collapsed in June 2025,31 so it remains to be seen how this plan unfolds, but adoptees are cautiously optimistic. They will remain vigilant and involved in the debates concerning ICA because the resistance by the pro-adoption lobby continues.32 Adoptees will also continue the fight for government support for their search for origins and identity restoration. The government issues letters with plans regarding support for adoptees. However, the proposals still fall short of what is needed to reach justice for them, their families who lost them, and for children and families in similar conditions who are at risk of being separated and displaced.

Despite the personal toll that activism takes, most adoptees—like other social justice activists—find fulfilment in fighting for their cause and changing the narrative to the reality of their shared experience and knowledge about the system. That is also why the respondents all agreed to be interviewed for this study, even though the topics stirred up emotions. The respondents felt comfortable sharing their stories with fellow adoptees, hoping that this article contributes to their cause. On the final day of the FAR FROM HERE event, team member Charlie Paauwe shared these inspirational words on behalf of the critical adoptee coalition:

“We’re not there yet—far from it—but I invite you to continue together. From every corner of the world, we raise our voices. We translate for those who don’t understand us, we devour the lies of our pasts, and we reclaim our stories so that they are never forgotten. Cut our roots, relocate, and repot us in foreign soil, but our branches will never perish, and our blossoms will never wither. We continue.”33

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.d.V., S.J.P.d.V. and K.E.C.; methodology, S.K.d.V., S.J.P.d.V. and K.E.C.; formal analysis, S.K.d.V., S.J.P.d.V. and K.E.C.; investigation, S.K.d.V. and S.J.P.d.V.; resources, S.K.d.V. and S.J.P.d.V.; data curation, S.K.d.V. and S.J.P.d.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.d.V.; writing—review and editing, S.K.d.V., S.J.P.d.V. and K.E.C.; visualization, S.K.d.V.; project administration, S.K.d.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Light Track of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences (protocol code ECSW-LT-2025-9-29-15869 and 2025-09-29 of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all adoptees that engage(d) in activism, in the Netherlands and beyond, as well as their allies, for paving the way for and/or cooperating with the authors in their academic and activism work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The three main questions and sub questions (or prompts) used in the interviews are:

- How/when did your life trajectory as adoptee lead to activism?

- Explaining the touchstones of the ACM to kick off the interview

- Considering the touchstones, what happened to make you decide to engage in activism?

- In which ways did you engage in activism, which type(s) of activism did you engage in and with what purpose?

- Explaining what we consider to be activism (broad spectrum).

- With whom did you cooperate, within and outside the adoptee community?

- What did it bring you (positive/negative)?

- Which effects/impact did you see/experience?

- Making sure all (relevant) key moments in the ICA debate were addressed.

- Did you lobby with ministries/civil servants, ministers, members of parliament, and what effects did you see?

- Did you reach the public (adoptee community/broader public), and what effects did you see?

- Did you appear in the media?

- Did you experience resistance and if yes, from whom (personal circle, public, pro-adoption lobby)?

Notes

| 1 | https://www.studiodebakkerij.nl/ver-van-hier/ (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 2 | Music, dance, film, performance art, visual arts, talks, rituals and workshops. |

| 3 | https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/specialised-sections/intercountry-adoption (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 4 | The first author was an active member of the adoptee organisation from Bangladesh, also knowing about the other organisations. Hoksbergen (2011) includes a list of these organisations in his book. |

| 5 | The authors deliberately chose not to use the word ‘biological’ referring to the (first/original) parents of adoptees as it diminishes their role and puts their existence in the shadow of the adoptive parents. |

| 6 | Example from Colombia: https://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/met-dna-kit-en-wat-wangslijm-op-zoek-naar-kind-in-holland~b7d4fbfb/ (accessed on 1 November 2025); and from Bangladesh: https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2176446-adoptiekinderen-bangladesh-zonder-medeweten-van-ouders-naar-nederland-gebracht (accessed on 1 November 2025). |

| 7 | Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie 2021, Appendix C: Legal framework intercountry adoption. |

| 8 | Others were also instrumental in shifting the narrative, such as Roelie Post (Post 2007) and Ina Hut (Hut 2023). |

| 9 | E.g., to this day, there is no individual financial support available for adoptees for family searches, DNA tests, legal costs, or psychological support (https://www.defenceforchildren.nl/media/6171/input-ao-interlandelijke-adoptie-dci-comensha-icdi.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025); https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2582288-geld-voor-zoektocht-na-adoptie-komt-maar-bij-handjevol-geadopteerden-terecht (accessed on 14 September 2025)). |

| 10 | https://defenceforchildren.nl/media/7009/statement-interlandelijke-adoptie-24-06-24.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 11 | Source: statement by Shila during the VER VAN HIER talk show. |

| 12 | https://www.bnnvara.nl/zembla/artikelen/dit-is-ons-dossier-over-adoptiebedrog-1 (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 13 | Part 1: https://omroepzwart.nl/programmering/de-afhaalchinees (accessed on 14 September 2025), nominated for the Nipkowschijf and the Dutch Directors Guild Award and selected for the debut competition of the Dutch Film Festival (Source: https://www.oneworld.nl/identiteit/kelly-qian-van-binsbergen-als-ik-buikpijn-krijg-van-een-idee-weet-ik-dat-ik-goed-zit/ (accessed on 14 September 2025)) and part 2 https://omroepzwart.nl/programmering/de-afhaalchinees-thuisbezorgd (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 14 | Dilani: https://nos.nl/artikel/2517378-sri-lankaanse-adoptiezaak-tegen-de-staat-moet-over (accessed on 14 September 2025); Patrick: https://www.ad.nl/binnenland/hof-diplomaat-betrokken-bij-babyroof-uit-brazilie-maar-toch-is-nederlandse-staat-niet-aansprakelijk (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 15 | www.brazilbabyaffair.org (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 16 | https://wnl.tv/2022/10/12/de-staat-gaat-naar-hoge-raad-in-zaak-onrechtmatige-adoptie-verbijsterd (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 17 | www.ojau.nl (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 18 | https://www.tweedekamer.nl/debat_en_vergadering/commissievergaderingen/details?id=2017A01091 (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 19 | https://www.stichtingaran.nl/ (accessed on 14 September 2025); www.brazilbabyaffair.org (accessed on 14 September 2025); www.rootsindonesie.nl (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 20 | https://www.unitedadoptees.org/nl/ (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 21 | https://www.linkedin.com/posts/icdichilddevelopment_satement-interlandelijke-adoptie-activity-7210944881869930498-6LRJ?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAAM_DrEBkt1z1w8WOfTA7109CdHR4lKubuM (accessed on 14 September 2025); https://www.defenceforchildren.nl/media/6171/input-ao-interlandelijke-adoptie-dci-comensha-icdi.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 22 | https://www.unitedadoptees.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Brief-Vaste-Kamer-Commissie-Justitie-2017.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 23 | https://omroepzwart.nl/artikelen?page=1&f=interview (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 24 | |

| 25 | Referring a.o. to InterCountry Adoptee Voices (ICAV), led by Lynelle Long. |

| 26 | E.g., adoptee session at national anti-racism event and events organised by Flemish/Dutch adoptee advocacy organization Critical Adoptees Fron Europe, or podcast LaVida. |

| 27 | E.g., (former) Minister Dekker mentioned the influence of adoptees in his speech upon receipt of the Joustra Report (https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/toespraken/2021/02/08/toespraak-door-minister-dekker-bij-de-in-ontvangstneming-van-het-rapport-van-de-commissie-joustra (accessed on 14 September 2025)), and (former) State Secretary Struycken in his letter to Parliament about the plan to phase out ICA (https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2024/12/09/tk-afbouwplan-interlandelijke-adoptie) (accessed on 1 November 2025). Also Parliamentarians often refer to adoptees (and/or their organisations, statements, etc.) in debates. |

| 28 | https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2024/12/09/zorgvuldige-afbouw-interlandelijke-adoptie-in-zes-jaar-tijd (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 29 | Motion dated 11 April 2024—Motion of member Van Nispen about a new plan to carefully phase out intercountry adoption. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/debat_en_vergadering/plenaire_vergaderingen/details/activiteit?id=2024A02882 (accessed on 14 September 2025). |

| 30 | Not their own. |

| 31 | https://ecre.org/op-ed-the-fall-of-the-dutch-government-that-took-longer-than-expected/ (accessed on 1 November 2025). |

| 32 | Prospective adoptive parents filed a complaint about starting a new adoption procedure and won (https://www.nederlandseadoptiestichting.nl/nieuws/adoptieouders-winnen-bezwaarprocedure/) (accessed on 1 November 2025). |

| 33 | Abbreviated version of Charlie Paauwe’s opening speech on the final day of FAR FROM HERE, introducing the theme of that day: ‘FURTHER’. |

References

- Anderson, Gary, and Kathryn Herr. 2007. Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, Denise, Annabel Ahuriri-Driscoll, and Barbara Sumner. 2023. Adoptee Activism: I Am Not Your ‘Child for All Purposes’. Counterfutures 14: 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, Susan F., JaeRan Kim, Grace Newton, Stephanie Kripa Cooper-Lewter, and Paula O’Loughlin. 2023. Out of the Fog and into Consciousness: A Model of Adoptee Awareness. International Body Psychotherapy Journal 22: 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cawayu, Atamhi. 2023. Searching for Restoration: An Ethnographic Study of Transnational Adoption from Bolivia. Ghent: Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte. [Google Scholar]

- Cawayu, Atamhi, and Hari Prasad Sacré. 2024. Can first parents speak? A Spivakean Reading of first parents’ agency and resistance in transnational adoption. Genealogy 8: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Cher Weixia, and Paul C. Gorski. 2015. Burnout in Social Justice and Human Rights Activists: Symptoms, Causes and Implications. Journal of Human Rights Practice 7: 366–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, Kristen. 2014. “Giving Children a Better Life?” Reconsidering Social Reproduction, Humanitarianism and Development in Intercountry Adoption. The European Journal of Development Research 26: 247–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, Kristen E. 2023. Why The Hague Convention Is Not Enough: Addressing Enabling Environments for Criminality in Intercountry Adoption. In Organized Crime in the 21st Century. Edited by Hans Nelen and Dina Siegel. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Seungmi, Linda Banda, and Christine Velez. 2025. Affirming Korean Adoptee Anti-Adoption Self-Expressions as Anti-Racist, Abolitionist Articulations: Blog Comment Reactions to Adopter Savior Syndrome. Abolitionist Perspectives in Social Work 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chovanec, Donna M., and Elizabeth A. Lange. 2007. Formative, Restorative and Transformative Learning: Insights into Formative, Restorative and Transformative Learning: Insights into the Critical Consciousness of Social Activists. Paper presented at Adult Education Research Conference, Halifax, NS, Canada, June 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie. 2021. Rapport Commissie Onderzoek Interlandelijke Adoptie [Report Committee Investigation Intercountry Adoption]. The Hague: Rijksoverheid. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, Shila Khuki, Sara Kinsbergen, and Dirk-Jan Koch. 2025. Towards a Critical Development Perspective on Intercountry Adoptions. Oxford Development Studies 53: 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, Shila Khuki, Sara Kinsbergen, and Dirk-Jan Koch. forthcoming. Adoption Agencies and the Market for Inter-nationally Adoptable Children.

- Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Gesteira, Soledad, Irene Salvo Agoglia, Carla Villalta, and Karen Alfaro Monsalve. 2021. Child appropriations and irregular adoptions: Activism for the “right to identity,” justice, and reparation in Argentina and Chile. Childhood 28: 585–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoksbergen, René. 2011. Kinderen Die Niet Konden Blijven; Zestig Jaar Adoptie in Beeld. Soesterberg: ASPEKt. [Google Scholar]

- Hübinette, Tobias. 2004. Adopted Koreans and the Development of Identity in the “Third Space”. Adoption & Fostering 28: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübinette, Tobias. 2025. The Swedish Adoption World and the Process of Coming to Terms with Transnational Adoption. Genealogy 9: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hut, Ina. 2023. Vraag Creëert Aanbod: Interlandelijke Adoptie Is Verworden Tot Een Verziekt Systeem van Marktwerking. In Voorbij Transnationale Adoptie: Een Kritische En Meerstemmige Dialoog. Edited by Sophie Withaeckx, Atamhi Cawayu and Chiara Candaele. Brussels: Academic & Scientific Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Juffer, Femmie, and Rien van IJzendoorn. 2016. Adoptie-advies RSJ is slecht onderbouwd. de Volkskrant. December 2. Available online: https://www.volkskrant.nl/columns-opinie/adoptie-advies-rsj-is-slecht-onderbouwd~b62ffae5/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Kim, JaeRan, Susan F. Branco, and Grace Newton. 2025. Exploring Transracial Adoptees’ Experiences of Developing Adoption Consciousness. Adoption Quarterly, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Dirk-Jan, and Olga Burlyuk. 2020. Bounded Policy Learning? EU Efforts to Anticipate Unintended Consequences in Conflict Minerals Legislation. Journal of European Public Policy 27: 1441–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruijsse-Brugge, Joe Lize. 2024. Is the end coming for intercountry adoption in Europe? Christian Network Europe. January 26. Available online: https://cne.news/article/4079-is-the-end-coming-for-intercountry-adoption-in-europe (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Loibl, Elvira C. 2021. The Aftermath of Transnational Illegal Adoptions: Redressing Human Rights Violations in the Intercountry Adoption System with Instruments of Transitional Justice. Childhood 28: 477–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, Elvira C., and David Smolin, eds. 2024. Facing the Past: Policies and Good Practices for Responses to Illegal Intercountry Adoptions. The Hague: Eleven Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mookherjee, Nayanika. 2022. Irreconcilable Times. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 28: 153–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, Roelie. 2007. Romania: For Export Only: The Untold Story of the Romanian ‘Orphans’. St. Annaparochie: Hoekstra. [Google Scholar]

- Raad voor Strafrechtstoepassing en Jeugdbescherming. 2016. Bezinning Op Interlandelijke Adoptie. The Hague: Raad voor Strafrechtstoepassing en Jeugdbescherming. [Google Scholar]

- Schrover, Marlou. 2023. “Al Red Je Er Maar Één”. Interlandelijke Adoptie in Nederland (1880–2022). In Voorbij Transnationale Adoptie: Een Kritische En Meerstemmige Dialoog. Edited by Sophie Withaeckx, Atamhi Cawayu and Chiara Candaele. Brussels: Academic & Scientific Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, David. 2024. Introduction. In Facing the Past: Policies and Good Practices for Responses to Illegal Intercountry Adoptions. The Hague: Eleven Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Withaeckx, Sophie. 2024. The Baby and the Bathwater: Resisting Adoption Reform. In Facing the Past: Policies and Good Practices for Responses to Illegal Intercountry Adoptions. The Hague: Eleven Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).