The Use of Child-Centered Ecomaps to Describe Engagement, Teamwork, Conflict and Child Focus in Coparenting Networks: The International Coparenting Collaborative Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Visual Mapping Devices in Clinical Settings: A Brief Overview

1.2. Evaluating Coparenting: The ICC Approach

2. Materials and Methods

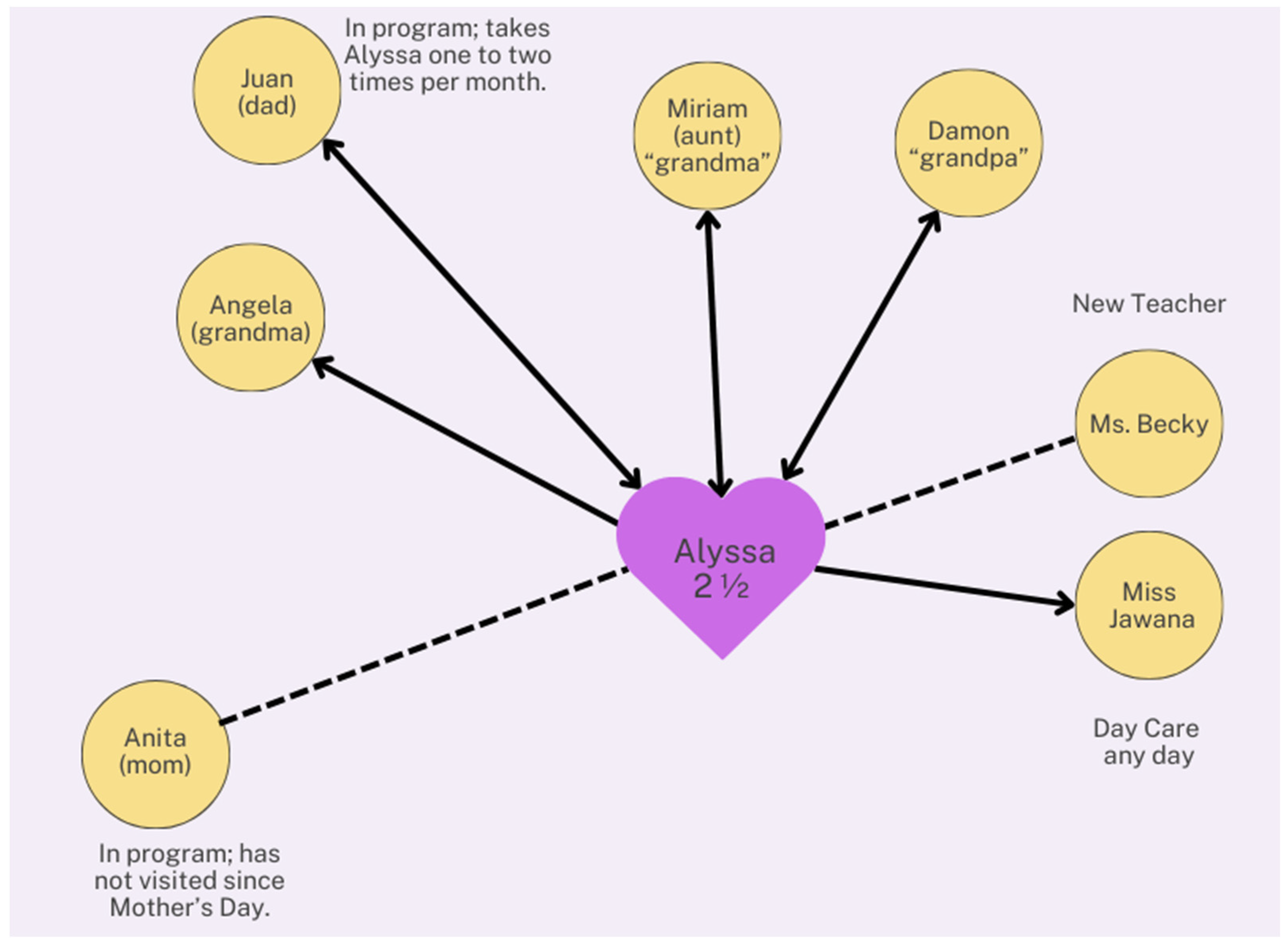

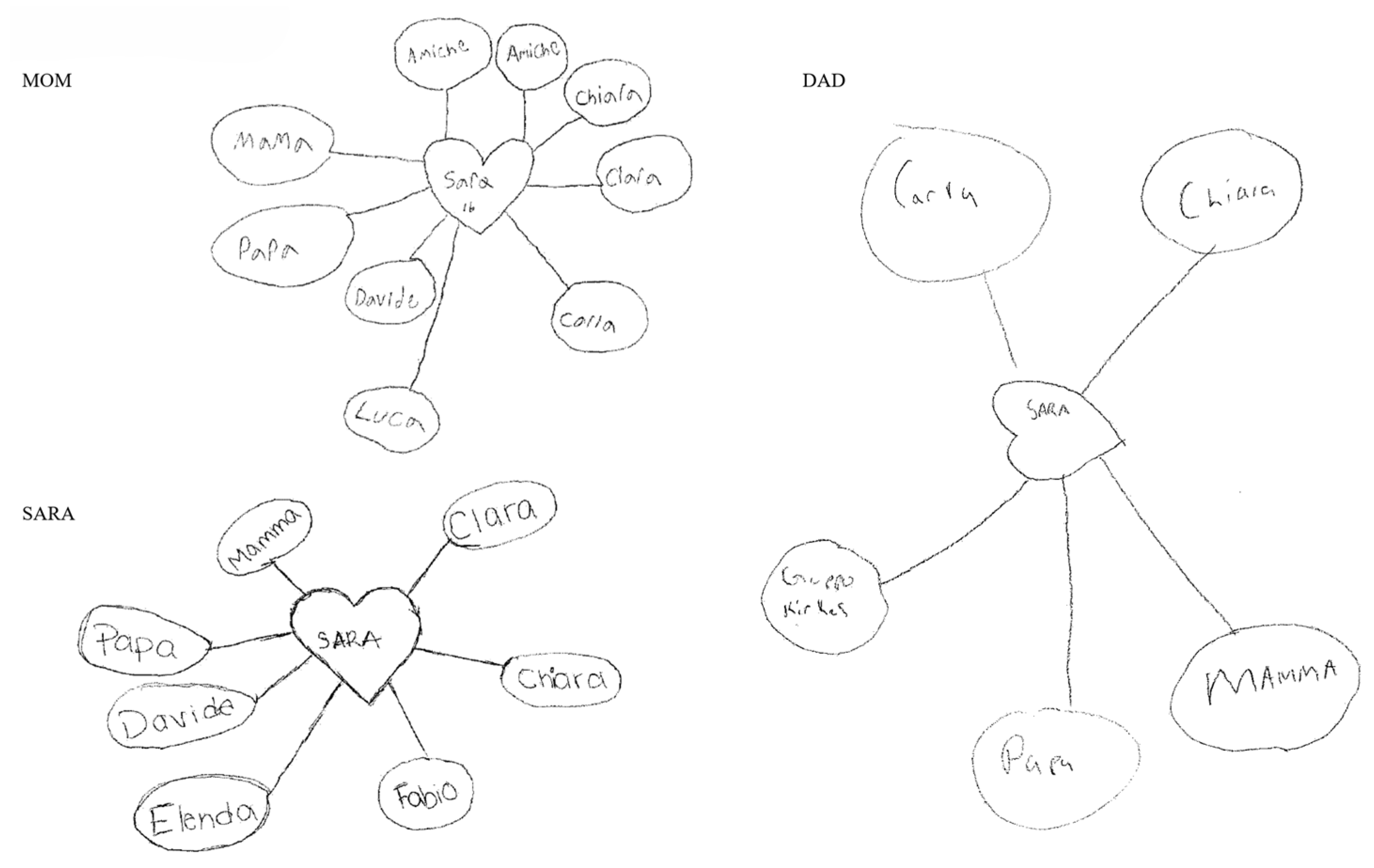

“Nearly all young children develop close bonds or “heart connections” with important others. Please put your child’s name and age in the heart below. Next, draw circles that represent each of the important people in your child’s life, putting each person’s circle close to or farther away from your child’s heart to indicate how frequently your child sees, visits, or calls that person. Then connect each circle to the heart with a solid line for especially emotionally strong bonds, and a dotted line for others who are loved, but just not quite as emotionally close”.

- Promoting Engagement for All

- Supporting and Teaming with One Another

- Containing and Minimizing Child-Related Conflict

- Assuring the Child is Seen and Heard

3. Results

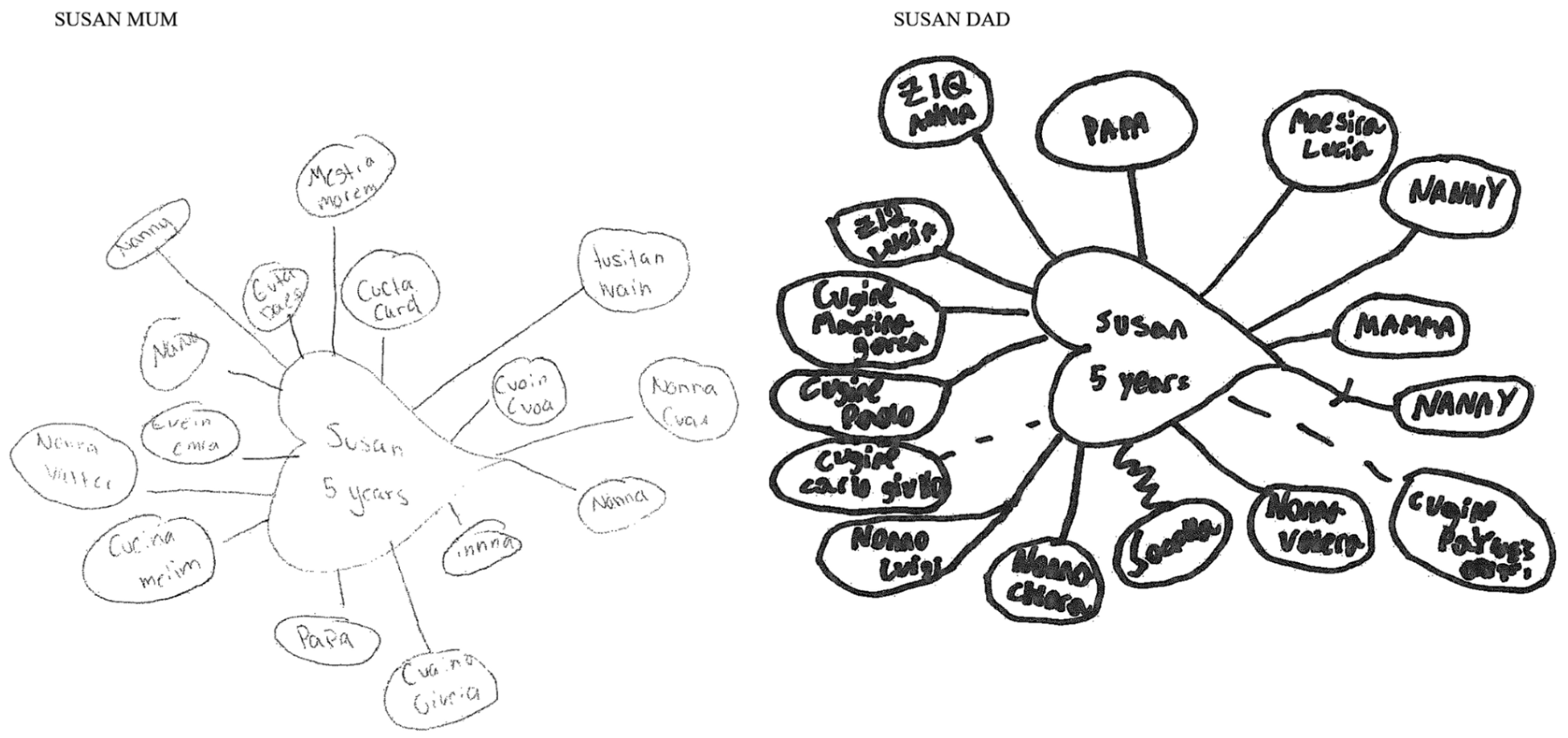

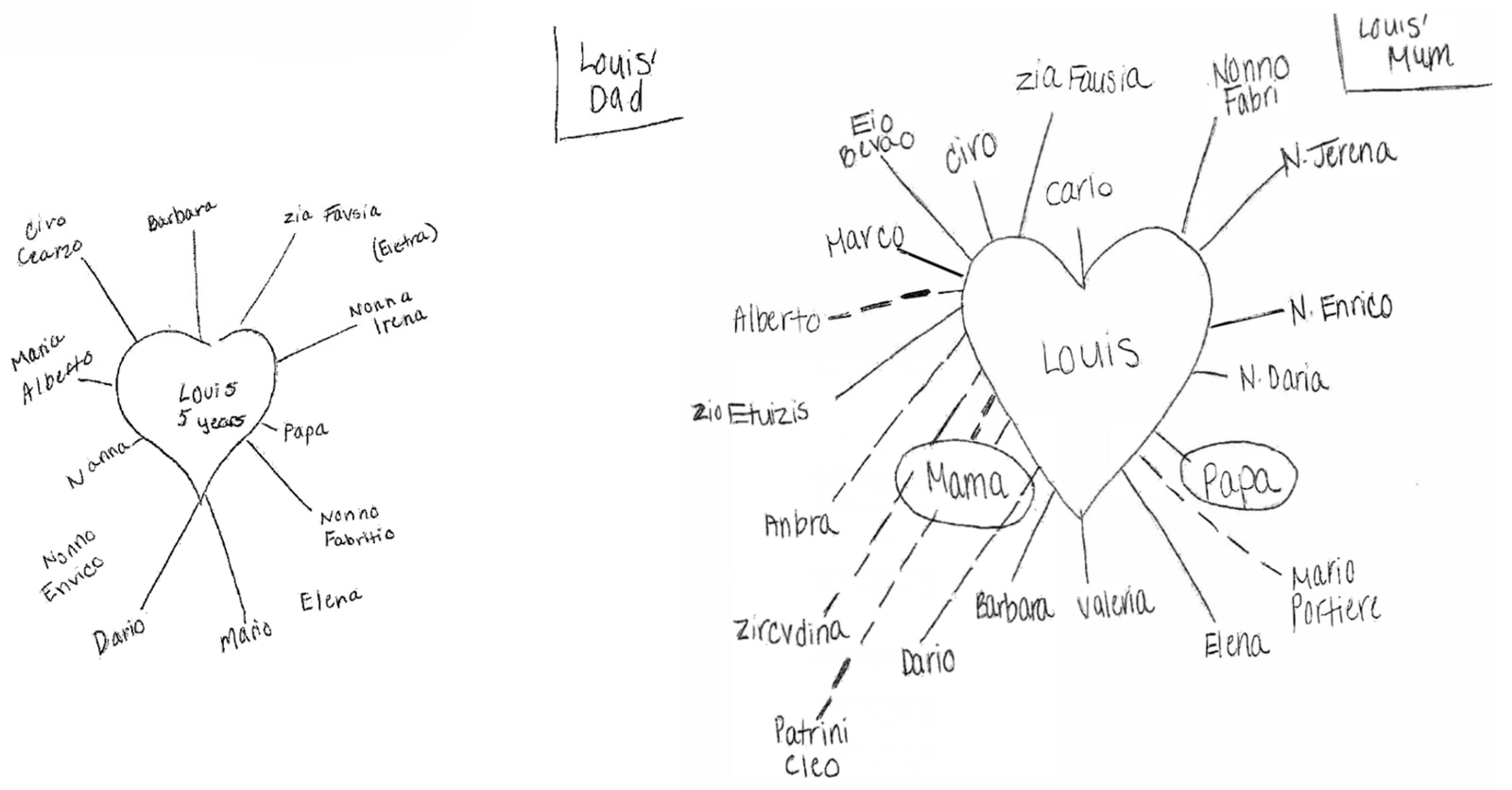

3.1. Application of the ICC Model with Families of Young Children: Four Cases from Rome, Italy

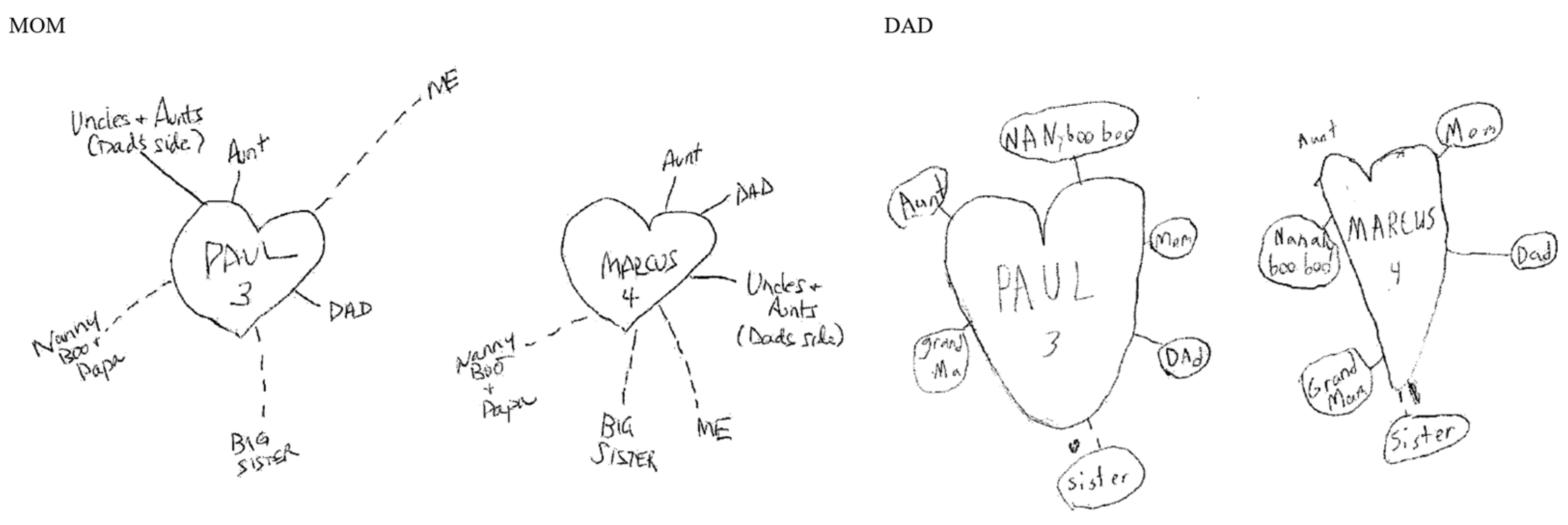

3.2. Application of the ICC Model with a Child Welfare-Involved Case with Extended Family Coparents

3.3. ICC Ecomapping by Both Coparents and Their Adolescent Children: Two Cases from Pavia, Italy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This content is excluded from all forms of open access license, including Creative Commons, and the content may not be reused without the permission of Oxford University Press—details of how to obtain permission can be found at https://global.oup.com/academic/rights/permissions/?cc=gb&lang=en& (accessed on 12 August 2025). |

References

- Baradel, Giorgia, Livio Provenzi, Matteo Chiappedi, Marika Orlandi, Arianna Vecchio, Renato Borgatti, and Martina Maria Mensi. 2023. The Family Caregiving Environment Associates with Adolescent Patients’ Severity of Eating Disorder and Interpersonal Problems: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 10: 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bein, Victoria, Damián Javier Ursino, and María Daniela Pérez Chada. 2022. Parenting Alliance Measure: Factor Structure in an Argentinian Sample. Psychological Thought 15: 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradt, Jack O. 1980. The Family Diagram: Method, Technique and Use in Family Therapy. Washington, DC: Groome Center. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, John F. 2008. The family diagram and genogram: Comparisons and contrasts. The American Journal of Family Therapy 36: 169–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, Larry L. 1978. Family Sculpture and Relationship Mapping Techniques. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 4: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corboz-Warnery, Antoinette, Elisabeth Fivaz-Depeursinge, Christine Gertsch Bettens, and Nicolas Favez. 1993. Systemic analysis of father-mother-baby interactions: The Lausanne triadic play. Infant Mental Health Journal: Infancy and Early Childhood 14: 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockenberg, Susan C., Esther M. Leerkes, and Shamila K. Lekka. 2007. Pathways from marital aggression to infant emotion regulation: The development of withdrawal in infancy. Infant Behavior and Development 30: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartas Arias, Jorge Mauricio. 2017. Genogram: Tool for exploring and improving biomedical and psychological research. International Journal of Psychological Research 10: 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- DeMaria, Rita, Gerald R. Weeks, and Larry Hof. 2013. Focused Genograms: Intergenerational Assessment of Individuals, Couples, and Families. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliston, Donna, James McHale, Jean Talbot, Meagan Parmley, and Regina Kuersten-Hogan. 2008. Withdrawal from coparenting interactions during early infancy. Family Process 47: 481–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge, Elisabeth, and Antoinette Corboz-Warnery. 1999. The Primary Triangle: A Developmental Systems View of Mothers, Fathers, and Infants. New York: Basicbooks. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarolo, France, Nevena Dimitrova, Grégoire Zimmermann, Nicolas Favez, Regina Kuersten-Hogan, and Jason Baker. 2009. Presentation of the French adaptation of McHale’s coparenting scale. Neuropsychiatrie de L’enfance et de L’adolescence 57: 221–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennari, Marialuisa, Caterina F. Gozzoli, and Giancarlo Tamanza. 2024. Assessing family relationships through drawing: The Family Life Space. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1347381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Alice M., Philip A. Fisher, and Jennifer H. Pfeifer. 2013. What sleeping babies hear: An fMRI study of interparental conflict and infants’ emotion processing. Psychological Science 24: 782–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, Paul J., Laura F. Fay, Stephen L. Burden, and James G. Kautto. 1987. The Evaluation and Treatment of Marital Conflict. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Ann. 1978. Diagrammatic assessment of family relationships. Social Casework 59: 465–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, Ann. 1995. Eco-maps and eco-grams. In Family-Centered Practice: A Framework for Social Work Assessment. Edited by Joseph Mattaini. New York: Haworth Press, pp. 165–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Kent T., Robert S. Marvin, Glen Cooper, and Bert Powell. 2006. Changing toddlers’ and preschoolers’ attachment classifications: The Circle of Security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 74: 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Bindu, Sarah Dickenson, Allira McCall, and Erin Roga. 2023. Exploring the therapeutic effectiveness of genograms in family therapy: A literature review. The Family Journal 31: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, Michael E., and Murray Bowen. 1988. Family Evaluation: An Approach Based on Bowen Theory. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Konold, Timothy R., and Richard R. Abidin. 2001. Parenting alliance: A multifactor perspective. Assessment 8: 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefevre, Michelle. 2018. Communicating and Engaging with Children and Young People: Making a Difference. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Libbon, Randi, Jenna Triana, Alison Heru, and Ellen Berman. 2019. Family skills for the resident toolbox: The 10-min genogram, ecomap, and prescribing homework. Academic Psychiatry 43: 435–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangelsdorf, Sarah C., Daniel J. Laxman, and Allison Jessee. 2011. Coparenting in two-parent nuclear families. In Coparenting: A Conceptual and Clinical Examination of Family Systems. Edited by James P. McHale and Kristin M. Lindahl. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, Melanie C., and Patricia K. Kerig. 2002. Assessing coparenting in families of school-age children: Validation of the Coparenting and Family Rating System. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science 34: 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoldrick, Monica, Randy Gerson, and Sueli Petry. 2020. Genograms: Assessment and Treatment. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393714043. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, James P. 1997. Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process 36: 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHale, James P., and Kristin M. Lindahl. 2011. Coparenting: A Conceptual and Clinical Examination of Family Systems. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. xii–314. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, James P., and Susan Dickstein. 2019. The interpersonal context of early childhood development: A systemic approach to infant-family assessment. In Oxford Handbook of Infant, Toddler, and Preschool Mental Health Assessment, 2nd ed. Edited by Rebecca DelCarmen-Wiggins and Alice Carter. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, James P., Dannie Johnson, and Robert Sinclair. 1999. Family-level dynamics, preschoolers’ family representations, and playground adjustment. Early Education and Development 10: 373–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, James P., Erica E. Coates, Russia Collins, and Vicky Phares. 2024a. Coparenting theory, research, and practice: Toward a universal infant–family mental health paradigm. In WAIMH Handbook of Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health. Edited by Joy D. Osofsky, Hiram E. Fitzgerald, Miri Keren and Kaija Puura. Cham: Springer, pp. 329–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, James P., Herve Tissot, Silvia Mazzoni, Monica Hedenbro, Selin Salman-Engin, Diane A. Philipp, Joëlle Darwiche, Miri Keren, Russia Collins, Erica Coates, and et al. 2023. Framing the work: A coparenting model for guiding infant mental health engagement with families. Infant Mental Health Journal 44: 638–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, James P., Herve Tissot, Silvia Mazzoni, Monica Hedenbro, Selin Salman-Engin, Diane A. Philipp, Joëlle Darwiche, Miri Keren, Russia Collins, Erica Coates, and et al. 2024b. Framing the Work: A Coparenting Model for Guiding Infant Mental Health Engagement with Families. Practitioner’s Manual. Available online: https://osf.io/b4rn7/overview (accessed on 12 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mensi, Martina M., Marika Orlandi, Chiara Rogantini, Livio Provenzi, Matteo Chiappedi, Michela Criscuolo, Maria C. Castiglioni, Valeria Zanna, and Renato Borgatti. 2021. Assessing Family Functioning Before and After an Integrated Multidisciplinary Family Treatment for Adolescents with Restrictive Eating Disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 653047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moore, Ginger A. 2010. Parent conflict predicts infants’ vagal regulation in social interaction. Development and Psychopathology 22: 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostwin, Danuta. 1982. Ecological Therapy. The Life Space Approach. Baltimore: Loyola College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Opie, Jessica E., James P. McHale, Peter Fonagy, Alicia Lieberman, Robbie Duschinsky, Miri Keren, and Campbell Paul. 2023. Including the infant in family therapy and systemic practice: Charting a new frontier. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy 44: 554–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, David. 1989. The represented and practicing family: Contrasting visions of family continuity. In Relationship Disturbances in Early Childhood: A Developmental Approach. Edited by Arnold J. Sameroff and Robert N. Emde. New York: Basic Books, pp. 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Satir, Virginia M. 1972. Peoplemaking. Palo Alto: Science and Behavior Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shellenberger, Sylvia. 2007. Use of the Genogram with Families for Assessment and Treatment. In Handbook of EMDR and Family Therapy Processes. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Elizabeth R., Madeleine Clement, and Ginger Ledet. 2013. Postmodern and alternative approaches in genogram use with children and adolescents. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 8: 278–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Karen. 2010. The perspectives of young children in care about their circumstances and implications for social work practice. Child & Family Social Work 15: 186–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McHale, J.P.; Mazzoni, S.; Mensi, M.M.; Collins, R.; Busca, A.; Vecchio, A.; Riso, M. The Use of Child-Centered Ecomaps to Describe Engagement, Teamwork, Conflict and Child Focus in Coparenting Networks: The International Coparenting Collaborative Approach. Genealogy 2025, 9, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040119

McHale JP, Mazzoni S, Mensi MM, Collins R, Busca A, Vecchio A, Riso M. The Use of Child-Centered Ecomaps to Describe Engagement, Teamwork, Conflict and Child Focus in Coparenting Networks: The International Coparenting Collaborative Approach. Genealogy. 2025; 9(4):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040119

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcHale, James P., Silvia Mazzoni, Martina Maria Mensi, Russia Collins, Alice Busca, Arianna Vecchio, and Marina Riso. 2025. "The Use of Child-Centered Ecomaps to Describe Engagement, Teamwork, Conflict and Child Focus in Coparenting Networks: The International Coparenting Collaborative Approach" Genealogy 9, no. 4: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040119

APA StyleMcHale, J. P., Mazzoni, S., Mensi, M. M., Collins, R., Busca, A., Vecchio, A., & Riso, M. (2025). The Use of Child-Centered Ecomaps to Describe Engagement, Teamwork, Conflict and Child Focus in Coparenting Networks: The International Coparenting Collaborative Approach. Genealogy, 9(4), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040119