Abstract

Background: This systematic review examines the lived experiences of Black students in UK higher education (HE), focusing on their encounters with racism and racial disadvantage, and how institutional and social factors contribute to these experiences. Methods: We conducted a systematic search across seven databases (Academic Search Complete, Education Abstracts, PsycINFO, Race Relations Abstracts, Scopus, Web of Science, and SocINDEX) in April 2023, with periodic updates. The grey literature, which refers to research and information produced outside of traditional academic publishing and distribution channels, was reviewed. This includes reports, policy briefs, theses, conference proceedings, government documents, and materials from organisations, think tanks, or professional bodies that are not commercially published or peer-reviewed but can still offer valuable insights relevant to the topic. Hand searches were also included. Studies were included if they were peer-reviewed, published between 2012 and 2024, written in English, and focused on the experiences of Black students in UK higher education. Both qualitative and quantitative studies with a clear research design were eligible. Studies were excluded if they lacked methodological rigour, did not focus on the UK HE context, or did not disaggregate Black student experiences. Risk of bias was assessed using standard qualitative appraisal tools. Thematic analysis was used to synthesise findings. Results: Nineteen studies were included in the review. Two main themes emerged: (1) diverse challenges including academic barriers and difficulties with social integration, and (2) the impact of racism and institutional factors, such as microaggressions and biased assessments. These issues contributed to mental fatigue and reduced academic performance. Support systems and a sense of belonging helped mitigate some of the negative effects. Discussion: The evidence was limited by potential bias in reporting and variability in study quality. Findings reveal persistent racial inequalities in UK HE that affect Black students’ well-being and outcomes. Institutional reforms, increased representation, and equity-focused policies are needed. Future research should explore effective interventions to reduce the awarding gap and support Black student success

1. Introduction

Racial disparity in UK higher education (HE) is evident in various forms, including differences in graduation outcomes, employment prospects, the white–Black awarding gap, and high dropout rates (McCabe and Pollard 2023; Arday et al. 2022; Wong et al. 2021). This review aims to explore the lived experiences of Black students, focusing on racism and racial disadvantage. The study uses a qualitative thematic synthesis approach to provide a comprehensive understanding of these challenges. The review highlights the persistent racial inequalities in HE and emphasises the importance of addressing these disparities to improve student experiences and outcomes. The terminology debate surrounding terms like BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) and BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) is acknowledged, with the review opting for “Black” to ensure specificity. By synthesising qualitative research, this review contributes to advancing equity and inclusion in UK universities.

2. Search Strategy

This search strategy, which started in April 2023, was a continuous process, and it was repeated throughout the research and at different stages. The study developed search strategies on 7 databases: Academic Search Complete, Education Abstract, PsycINFO, Race Relations Abstracts, Web of Science, Scopus, and SocINDEX. In addition, a manual hand search of reference lists and related citations was carried out. The ‘grey literature’ was also considered, because it is often more current than published literature and is often considered to have less publication bias (Paez 2017). Endnote was used to save references, with duplications deleted. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklist (CASP) was used to assess bias. A themed approach was used to explain the findings. The following table (Table 1) presents key terms adopted in the literature search, using phrase search (putting search terms in a phrase between quotation marks) and Boolean operators (‘AND’ or ‘OR’), with the truncating symbol (*) used to narrow the search to useful hints:

Table 1.

Search strategy.

Quotation marks were used around key phrases for the exact terminology to be included in the search. The truncating symbol (*) was used to narrow the search to useful hints and to allow associating terms with different endings to be included. Terms were searched for in the titles and abstracts of the paper to ensure irrelevant articles were not included with the relevant ones.

Two searches were run:

The first search included terms 1, 2, and 3. The second search, involved hand searching, snowballing, and the grey literature.

- Selection Process

All retrieved records were initially screened for relevance based on title and abstract. Full-text articles were then reviewed to assess eligibility according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The primary reviewer (the lead author) conducted all screening and selection. To support the process and reduce potential bias, the university librarian assisted with accessing full texts and verifying inclusion criteria during full-text screening. However, the lead author made all final inclusion decisions. No automation tools were used in the selection process.

- Data Collection Process

Data were extracted from the included studies by the lead author using a structured data extraction form developed for the review. The librarian assisted in locating and retrieving full-text articles but did not participate in data extraction. No automation tools were used. Where clarification was needed, data were rechecked against the source material, but no contact with study authors was made.

- Data items

Data collected included outcomes related to Black students’ lived experiences of racism and racial disadvantage within UK higher education. This encompassed themes such as academic barriers, social integration, and institutional factors. Additional variables extracted included study design, sample size, participant demographics (e.g., level of study, home/international status), and methodological approach. When data were unclear or missing, information was excluded rather than imputed.

- Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias for each included study was assessed independently by the lead author using the CASP checklist for qualitative studies. No automation tools were used. Due to resource constraints, a second reviewer was not involved.

- Effect Measures

As this review synthesises qualitative data, effect measures such as risk ratios or mean differences were not applicable. Instead, findings were summarised thematically based on the presence and prevalence of key themes across studies.

- Synthesis methods

- Eligibility for Synthesis

All studies included in the review were assessed against the predefined inclusion criteria (see Table 2). Studies were deemed eligible for synthesis if they contained relevant qualitative data on Black students’ experiences of racism and racial disadvantage in UK higher education, even when part of a mixed-methods design. Disaggregated qualitative data from mixed-methods studies were extracted and included. A data extraction table was created to summarise study characteristics (e.g., design, participants, data collection, analysis method), ensuring comparability across included sources.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Data Preparation

To prepare for synthesis, relevant findings from each study were extracted and coded using NVivo. Data were cleaned to ensure only relevant themes aligned with the review objective were included. As the synthesis focused on qualitative themes, there were no statistical conversions or imputation of missing numeric data. Where studies lacked detail, only clearly reported findings were used.

- Tabulation and Visual Display

The characteristics of the 19 included studies were tabulated, including information such as study design, participant type (e.g., home/international), data collection methods, and theoretical frameworks. A thematic table was used to organise emergent themes and subthemes. In addition, tables were created to visually represent key findings across studies (included in the Results Section).

- Method of Synthesis and Rationale

A thematic synthesis approach, informed by Thomas and Harden (2008), was used to identify, analyse, and report patterns across the studies. This method was chosen due to its suitability for synthesising qualitative research and its ability to retain the contextual richness of primary studies while producing new conceptual insights. The process involved

- Line-by-line coding of extracted data;

- Development of descriptive codes;

- Grouping of codes into analytical themes;

- Refinement into overarching concepts.

This approach enabled the identification of both commonly reported experiences (e.g., microaggressions, social isolation) and more nuanced institutional patterns (e.g., structural disadvantage, resistance narratives).

- Exploration of Heterogeneity

Conceptual heterogeneity was explored by comparing themes across different study characteristics, such as

- Level of study (undergraduate vs. postgraduate);

- Student status (home vs. international);

- Theoretical frameworks used.

This allowed for examination of how contextual or methodological differences influenced reported experiences. However, no subgroup analyses or meta-regressions were applicable given the qualitative nature of the data.

- Sensitivity Analysis

While formal sensitivity analysis was not feasible, an internal quality check was performed. Studies with weaker methodological clarity were reviewed to assess whether their inclusion significantly altered the thematic synthesis. Their impact was minimal, and all included studies were retained. Themes supported by only one or two studies were critically appraised but still reported if conceptually significant.

3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

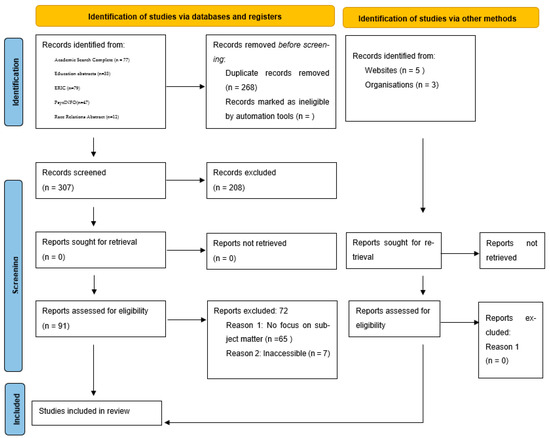

For the relevant literature to be selected for this study, the researcher applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The figure (Figure 1) below illustrates this.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram; PRISMA—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. This work is licenced under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

Data collection—All search results were saved to Endnote, and duplicates were removed.

Below is the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Prisma) Diagram.

3.1. Critical Appraisal Tool

All the included articles were critically appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP 2018) checklist for qualitative research. Each article underwent assessment using the CASP tool to evaluate its quality, with quality grades in the range of one (low), two (moderate), and three (high).

3.2. CASP Checklist

- (1)

- Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

- (2)

- Is the qualitative methodology appropriate?

- (3)

- Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

- (4)

- Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

- (5)

- Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

- (6)

- Has the relationship between the researcher and participants been adequately considered?

- (7)

- Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

- (8)

- Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

- (9)

- Is there a clear statement of findings?

- (10)

- How valuable is this research?

3.3. Ethics

As part of the quality test of the CASP, ethical consideration is important; if an article does not explicitly address ethical issues, this affects the CASP rating. Most of the included studies demonstrated ethical awareness, particularly due to

- The sensitivity of the subject matter—Many participants were asked to share personal and sometimes traumatic experiences related to racism and exclusion in higher education. Researchers often took care to ensure emotional well-being by providing participants with the option to withdraw, access support resources, or decline to answer particular questions.

- Power imbalances in the interview process—Given that many interviewers held academic or institutional positions, several studies acknowledged the potential for perceived authority to influence participant responses. Ethical practices such as building rapport, using participant-led interviews, and anonymizing responses were used to mitigate this.

- Confidentiality and anonymity—Due to the relatively small number of Black students in certain institutions or disciplines, participants could be more easily identifiable. Some studies implemented extra safeguards (e.g., removing institutional names, using pseudonyms, or generalising contextual details) to protect participant identities.

Most of the included articles had ethical considerations in mind due to (i) the sensitivity of the subject matter, particularly when participants had to recant negative experiences; and (ii) the power imbalance during the interviews.

4. Results

4.1. Included Studies

Figure 1 illustrates the progression of the review process, detailing the number of articles identified and excluded at each stage. Initially, five hundred and seventy-six references were retrieved through the search methods, resulting in three hundred and seven unique citations after duplicate removal. Subsequent title screening led to the exclusion of two hundred and eight articles due to a lack of relevance or availability. Following abstract and full-text assessment, ninety-nine articles were reviewed, with eighty ultimately excluded based on inaccessibility or insufficient alignment with the research focus. Ultimately, nineteen articles were included in the final sample.

Table 3 presents the key characteristics of the included papers.

Table 3.

Analysis of included literature.

4.2. Characteristics and Summary of the Included Articles

This systematic review and qualitative synthesis identified nineteen publications. The publications ranged from qualitative to mixed (qualitative and quantitative) techniques. Despite being a qualitative synthesis, publications with pertinent qualitative data disaggregated from the mixed-method findings were included in the study.

4.3. Methods (Data Collection)

In this review, thirteen out of the nineteen studies utilised interviews as their primary data-gathering method, while four studies employed focus groups. Among the interview types used, semi-structured interviews were the most common (n = 8), followed by interviews (n = 3), in-depth interviews (n = 1), and phenomenological interviews (n = 1). Additionally, some studies employed both interviews and focus groups.

Quality Appraisal

To assess the quality of the included studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research was used. Each study was reviewed using the CASP criteria, focusing on methodological rigour and credibility. Based on the appraisal, studies were assigned a quality rating: Level 1 (high), Level 2 (moderate), or Level 3 (low). Of the 19 included studies, 3 received a Level 2 rating, and 16 received a Level 3 rating.

4.4. Data Analysis

Out of the nineteen articles reviewed, fifteen employed various data analysis techniques. These included Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (n = 1) and thematic analysis (n = 13), for example, Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis. Among the thematic analysis studies, one explicitly mentioned its use, while the others required inference from the content. Other data analysis methods included thick description [n = 1] (Ponterotto 2006).

4.5. Theoretical Framework

Twelve out of nineteen articles included in this synthesis declared a theoretical framework. These include CRT (n = 4), self-determination theory (n = 3), the hermeneutic phenomenological approach (n = 1), the flipped classroom approach (n = 1), the Push–Pull model, and Gidden’s (2014) structuration approach (n = 1); Social Identity Perspective (including Self-Categorisation Theory (n = 1); and social constructivism (n = 1).

4.6. Theoretical Framework Synthesis

This section examined the theoretical framework synthesis, a type of qualitative synthesis that integrates and analyses the theoretical frameworks used across multiple studies within this systematic review. Its goal was to offer a comprehensive understanding of how various theories have been applied, developed, or tested in the research area, highlighting the connections, similarities, and differences among these theoretical approaches.

Studies by Marandure et al. (2024), Taylor (2021), Bunce et al. (2021), and Bunce and King (2019) employed the self-determination theory (SDT). SDT posits that optimal achievement, motivation, and well-being are achieved by fulfilling three basic psychological needs: relatedness, competence, and autonomy. Interview questions were designed to explore these themes, such as “How well do you feel that you fit in with other students on the course?” (relatedness); “Do you feel that there are any barriers for you to achieve your full potential on the course?” (competence); and “Do you think you can be yourself on the course and discuss your ideas and opinions?” (autonomy).

These studies found that meeting students’ needs in these three areas was crucial. While the studies primarily focused on BME students, the experiences of Black students were notably discernible, hence their inclusion in this synthesis. SDT posits that satisfying these needs enhances motivation, engagement, and well-being, which are crucial for educational success. These studies highlighted the role of perceived support, competence in academic tasks, and autonomy in decision-making within educational settings. They emphasised how fostering a supportive environment that acknowledges and meets these needs can positively impact BME students’ educational experiences.

In their study, Marandure et al. (2024) unlike Taylor (2021), Bunce et al. (2021), and Bunce and King (2019), took a distinct approach by adopting an inductive coding and thematic analysis method. This approach allowed them to derive themes directly from the data while maintaining a theoretically informed interpretation of the findings. Unlike Bunce et al. (2021) and Bunce and King (2019), Marandure et al. (2024) opted for a data-driven approach, enabling them to explore students’ experiences comprehensively and uncover nuanced insights. By grounding their analysis in both theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence, they aimed to make direct comparisons with previous research. Specifically, they focused on understanding students’ perceptions of the reasons behind the awarding gap, facilitating a deeper exploration of the underlying factors contributing to disparities in academic outcomes.

Additionally, research by Ramamurthy et al. (2023), Pryce-Miller et al. (2023), Zewolde (2022), Stoll et al. (2022), and Wong et al. (2021) utilised CRT to examine systemic racism’s impact on BME students in HE. CRT critiques the structural inequalities embedded within educational institutions and society at large, highlighting how race and racism shape policies, practices, and everyday experiences. These studies explored themes such as racial microaggressions, stereotype threat, disparities in academic achievement, and institutional responses to racial discrimination. Zewolde’s study contends that CRT challenges assertions of “objectivity,” “meritocracy,” “colour-blindness,” and “race neutrality”, often propagated by institutions and dominant research paradigms, which tend to silence and disregard the perspectives of Black and ethnic minority individuals. Through a CRT-informed analysis, Black students are empowered to articulate their reality and amplify their voices, which are frequently overlooked or marginalised in the scholarly literature.

In Stoll et al. (2022), CRT-E was employed to confront and challenge racism within the framework of UK HE. However, the study argued that CRT-E overlooks the role of mental health in perpetuating racial inequality. This oversight prompted the researchers to utilise CRT-E, contending that according to the OFS (Office for students), Black students with mental health conditions exhibited some of the lowest rates of attainment, continuation, and progression. Additionally, they assert that the anti-Black racist system embedded within UK HE played a significant role in shaping the mental health experiences of these Black students. By focusing on BME students’ voices and experiences, CRT-oriented research challenges dominant narratives of meritocracy, which often overlook the systemic barriers BME students face. They advocated for anti-racist educational reforms, offering a hopeful vision for the future of HE.

Osbourne et al. (2021) applied Social Identity Theory to investigate how individuals categorise themselves based on salient social identities within educational contexts. This theory posits that individuals’ self-concept and behaviour are influenced by the social groups they identify with. This framework underscores the crucial role of inclusive educational practices in validating and supporting diverse social identities, promoting a sense of belonging and academic success among BME students.

Owusu-Kwarteng (2021) employed the Push/Pull factors model to explore BME students’ decisions to study abroad. This model examines the structural factors (push factors) that compel students to seek educational opportunities abroad and the attractive factors (pull factors) that draw students to study in other countries. It is particularly relevant in understanding how racial dynamics and global educational inequalities influence BME students’ educational choices and experiences.

The study by Miller and Nambiar-Greenwood (2022) employed a flipped classroom approach, considered a form of experiential learning (Zhai et al. 2017). This method prioritises student experiences, allowing participants to lead discussions in a safe environment. It was utilised to delve into issues of racism and cultural ‘othering’ experienced by racialised student nurses in both educational and practical settings. Specifically, the flipped classroom approach was employed during a communication seminar with a mixed group of adult and mental health students, fostering open discussions about racism that emerged during the session.

In Moula et al. (2024), the researchers utilised a social constructionism lens to investigate the perspectives and experiences of medical students from ethnically minoritised communities. This approach aimed to explore how these students conceptualise and interpret the world around them and how they articulated their understanding of their lived experiences.

The studies synthesise these perspectives comprehensively, collectively underscoring the multidimensional nature of BME students’ educational experiences. They emphasise the intersectionality of psychological factors, systemic inequalities, social identities, and global educational dynamics. This qualitative synthesis reveals the complexity of factors influencing BME students’ educational trajectories and calls for inclusive approaches that address both individual needs and structural barriers within HE. The findings of these studies have significant implications for educational practice and policy, suggesting the need for more inclusive and anti-racist approaches to education.

The preceding section provided an overview of the theoretical framework synthesis; the next section presents the identified synthesised themes.

4.7. Synthesised Findings

In the ensuing discussion, I present synthesised themes derived from the analysis of the findings of the included papers. Employing a thematic approach, I organise the evidence synthesis into two overarching themes: the range of experiences and the impact of racism and institutional factors. Within these broad themes, sub-themes are presented to encapsulate significant patterns observed across and within the included articles. This synthesis represents my critical examination of the existing literature on the experiences of Black students in HE and how race and racism influence these experiences. Throughout the presentation of these themes, I draw upon quotes from the original studies to substantiate the analysis presented. Table 4 shows number of articles associated with each theme.

Table 4.

Number of articles by theme and sub-theme.

4.8. Range of Experiences

4.8.1. Academic Competence: “Twice as Hard” or “Twice as Good”

Nine of the nineteen articles reviewed addressed how Black students grappled with perceived competence in their academic performance (Marandure et al. 2024; Pryce-Miller et al. 2023; Ramamurthy et al. 2023; Inyang and Wright 2022; Zewolde 2022; Bunce et al. 2021; Taylor 2021; Wong et al. 2021; Claridge et al. 2018). This theme explored the participants’ beliefs that overcoming obstacles required them to be “twice as good” or work “twice as hard” to counteract negative stereotypes and alter prevailing narratives.

In Inyang and Wright (2022), A Black student recounted, “I feel like I must work ten times harder to prove that I can use (this opportunity and do something). We can’t be vulnerable or express discomfort, even though we should be able to have these conversations to make work and education better” Pryce-Miller et al. (2023), documented the sentiment that working twice as hard went unacknowledged: “I have to work twice as hard, and this is not acknowledged.”

Also, Claridge et al. (2018) noted that “You have to be exceptional to be considered average”, while Marandure et al. (2024) described the overwhelming pressure of exceeding peers to meet these high expectations: “The pressure is kind of overwhelming, so like we’re trying our best to make sure that we succeed and we’re doing that better than our peers, but sometimes the pressure isn’t really good.”

Such pressures left Black students feeling compelled to over-perform compared to their white counterparts. This led to a complex of psychosocial issues where they felt they needed to constantly prove their worth against negative perceptions of their academic abilities. This overcompensation often prevented them from reaching their full potential, despite their strong work ethic and confidence.

Additionally, Black students described a pervasive sense being marked down; in other words, they believed they were given lesser scores than the work they put in, especially when compared with their white peers. The participants were disappointed in their grades and were left feeling they had not achieved their full potential. Moreover, after successful appeals, their grades were reviewed and increased. For instance, Bunce et al. (2021) reported a participant saying, “Yeah, I feel I put in a lot, that the grades that I got, they didn’t reflect on the work.” Ramamurthy et al. (2023) observed similar discrepancies: “When you did assignments and looked at your marks, you did not pass, and you go to your white friends because you want to see how to do it better. And you find that they’ve not done half the work. You’re thinking, how did that happen? They will say, ‘But yours is really good’ But I’ve got 40, and they’ve got 60/70.”

The participants tried to make sense of this experience by stating it was due to factors such as a lack of understanding of their cultural backgrounds and perspectives, framing it within their overall experience of injustice, which can translate into stereotypical perceptions of Black people lacking intellectual ability (Ramamurthy et al. 2023; Bunce et al. 2021).

Although there could be several possible causes as to why the grades differed, the participants in question perceived foul play. This is an essential reflection because it is synonymous with other participants’ experiences of feeling marked down because of their ethnicity. They may have grown to believe that because of negative societal stereotypes, their ethnicity will in some way affect their academic performance, which could lead to a lack of trust in the educational institution.

Black students often faced stereotypes when attempting to share their experiences or engage more actively, which only deepened their sense of exclusion. As Miller and Nambiar-Greenwood (2022) describe, this exclusion had significant mental health consequences. Students who spoke up were often labelled with negative stereotypes, such as “angry, loud, aggressive; they were branded as having a chip on their shoulder or playing the race card.” These labels compounded the emotional burden they faced.

Nonetheless, positive experiences were reported, including supportive feedback from some teachers and diverse ethnic representation among supervisors (Inyang and Wright 2022; Bunce et al. 2021).

4.8.2. Mental Health/Well-Being

Five of the nineteen articles discussed how negative academic experiences affected the mental health and well-being of Black students (Stoll et al. 2022). Encounters with exclusion or ‘Othering’ often led to feelings of isolation and a lack of belonging, contributing to mental health challenges (Zewolde 2022). For instance, a student described deteriorating mental health despite being competent, attributing this to negative feedback (Pryce-Miller et al. 2023): “My mental health is poor; I know I am competent but told I am too talkative, and I have conditioned myself to fail in practice.” This quote also suggests elements of gaslighting. Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation where a person is made to doubt their reality or competence.

This statement highlighted a student’s struggle with mental health and perceived competence. Despite their self-awareness of being competent, external feedback has caused them to question their abilities and condition themselves to expect failure. The student is told they are “too talkative,” which undermines their confidence. This feedback may be unfounded or exaggerated, contributing to self-doubt. Receiving a constant barrage of negative feedback, such as being labelled as too talkative, can profoundly impact a student’s self-esteem. This criticism becomes internalised, leading to a deterioration in their mental health and academic performance.

The student’s statement, “conditioned me to fail,” is a stark indication of the deep-rooted impact of negative feedback. It shows how the student has internalised this criticism to the point where they expect failure, regardless of their actual competence. This is a critical outcome of gaslighting, where the victim’s perception of reality is distorted.

Participants reported significant emotional distress from confronting racism and navigating an oppressive environment, which sometimes resulted in physical health issues, such as high blood pressure and sleep disturbances. They were exhausted by the “tide of oppression”. Some participants described feeling “anger and acute stress”, and others felt “emotionally unsafe”, and one participant recounted the negative impact on her and what it had done to her: “I developed high blood pressure and had to go on medication because I could not sleep”. Another described experiencing some delays in completing her academic work because of the toxic environment and how it affected her mental health (Ramamurthy et al. 2023).

The stigma around mental health also exacerbated their struggles, with stereotypes influencing their experiences in seeking support. Efforts to combat stereotypes often lead to additional stress (Claridge et al. 2018). The students believed that insensitivity to ethnicity permeated into spaces of support, where students already dealing with mental health issues must also navigate a lack of cultural understanding and racial stereotyping in the process.

Black students expressed the sentiment that they were often compelled to educate practitioners on Black culture and the Black experience, including how racism and microaggressions impacted their mental health. This additional responsibility placed a burden on their mental well-being. Consequently, Black students felt more at ease with mental health practitioners who shared their racial or ethnic background or belonged to other minoritised ethnic groups (Akel 2019). For example, one student noted, ”It was a white guy [support staff], it was okay; he kind of listened, but I mean, you could see he was thinking very carefully about what he was going to say. When I came back, I started seeing a Black woman counsellor. It was vital for me to have her because I don’t have time to explain racism and stuff like that” (Akel 2019). Some other participants went to their personal tutors instead because they believed they could be relatable. Others emphasised the need for comprehensive training for all counsellors to effectively relate to students from diverse backgrounds (Ramamurthy et al. 2023; Akel 2019).

These experiences taken together highlight the significance of having ethnically diverse counsellors on campus. The students’ experiences with racism had a detrimental impact on their feeling of community at university, their desire to socialise, their interactions with white students and faculty, and their academic success and advancement, all of which contributed to increased mental distress.

4.8.3. Isolation and Sense of Belonging

This theme centred on how Black students described feeling isolated and lacking a sense of belonging. The students had mixed perceptions on what determines a sense of belonging: internal factors (adapting to one’s environment) or external factors (creating an inclusive environment). Eleven out of the nineteen articles included in this study demonstrated how Black students felt invisible (Miller and Nambiar-Greenwood 2022), isolated, unwelcome, and excluded (Pryce-Miller et al. 2023; Stoll et al. 2022; Zewolde 2022; Bunce et al. 2021; Bunce and King 2019) when engaging with non-Black peers or lecturers. At university, Black participants reported being ignored or avoided by some non-Black peers in learning, social, and living environments, leading to feelings of lack of belonging. A participant in Zewolde (2022) recounted, “My presence was not welcomed; I was made to feel different.” Similarly, in Pryce-Miller et al. (2023), a respondent said, “I often feel my presence was not welcomed and I felt degraded and not belonging in this space.”

They believed this was due to the colour of their skin, which diminished their overall well-being and elicited a range of negative emotions, including distress and frustration. The Black students expressed their frustration and distress because of feeling alienated or excluded from their peer group due to their skin colour. A student in Taylor (2021) echoed the above experiences but described how her feeling of isolation stemmed from her African accent: “I was isolated, okay, I wasn’t the only Black person in the class, but I was the only mmm like I have African accent I didn’t have anyone to turn to um This is too painful I don’t want to go back there.” Some students in Pendleton et al. (2022) questioned their sense of belonging because of the systemic nature of the Eurocentric lens through which teaching was developed: “At university. A lot of learning is all based on white people… it’s all for people that are not dark skinned, but only Black or people from different backgrounds would notice this, others wouldn’t because they don’t need to think about it.”

Conversely, some students felt a strong sense of belonging due to supportive and diverse faculty, as well as positive interactions with peers (Inyang and Wright 2022; Bunce and King 2019). For instance, a student reported a feeling of liberation and comfort in a session discussing ethnicity and identity, while others found accommodating interactions with non-BME peers: “I really enjoyed one of our sessions; we were talking about ethnicity and identity, and I really enjoyed that lecture because I felt just, like, so liberated; I felt, like, so comfortable talking about, like real things that could affect me.” Additionally, some participants felt their non-BME cohorts were accommodating, and they felt they could fit in: “In terms of fitting in I can sit and engage with anyone, I can have a conversation with anyone, to be honest, and I think once we get talking, they’re quite accommodating. In terms of the class in general, I’ve got no issues” (Akel 2019). Additionally, In Bunce et al. (2021), one student expressed, “Lecturer A understands our concerns, she gets it, she could relate to it. And I think we need people like that, where we think we’ll feel safe, to go and talk to.”

On the other hand, another viewpoint on the issue of belonging addressed feelings of isolation and self-preservation. One participant mentioned spending time away from campus to avoid potential encounters with racial discrimination. This participant feared that immersing themselves too deeply in university life would increase the likelihood of experiencing racist incidents (Osbourne et al. 2023b).

These contrasting experiences highlight the importance of supportive faculty members and an inclusive environment in fostering a sense of belonging for Black students. While positive interactions with understanding lecturers and peers can enhance feelings of safety and inclusivity, the fear of discrimination may lead some students to distance themselves from campus environments.

4.8.4. Moderating Self and Coping Skills

Experiencing racialised treatment within social settings often led Black students to present a moderated version of themselves to avoid racially charged targeting.

The reviewed articles elaborated on racially charged targeting, defining it as instances where individuals faced discriminatory or prejudiced treatment based on their race or ethnicity. This targeting encompassed a spectrum of behaviours, ranging from verbal harassment and physical violence to exclusion, marginalisation, or microaggressions. Such mistreatment often originates from entrenched biases, stereotypes, or prejudices harboured by individuals or groups toward individuals of a specific racial or ethnic background. Importantly, this discriminatory behaviour can manifest in both overt and covert ways, making it pervasive and insidious. Its effects extend beyond immediate harm, leading to feelings of fear, alienation, frustration, and a diminished sense of self-worth among those subjected to it.

Black students disclosed that they felt compelled to censor themselves in academic environments to be perceived as acceptable and agreeable by white students and staff, rather than being labelled as loud, disruptive, or confrontational. This issue was addressed in eleven out of the nineteen articles included in the analysis.

Furthermore, they described how they could not be themselves on university campuses to avoid being perceived through the prism of unfavourable racial stereotypes; they strived to exhibit counter-stereotypic behaviour on campus. The term that best described this was supplied by Osbourne et al. (2023a) as “two versions of self”. Black students were more observant of their accent and often felt the need to change their accent on university grounds and or when relating to those who were non-Black or minority ethnic because they felt they would fit in more. For example, one narrated, “Oftentimes I’d modify the words I use or my accent to my ‘white voice’ to make people feel more comfortable” Another stated ‘there’s a lack of representation of my culture being shown, and so I feel the need to change to ‘fit’ in” (Akel 2019). A student in Marandure et al. (2024) recounts a similar experience: “I act presentable, I change my tone, like try to use bigger words when I’m talking so it’s like I just change everything cos if I act the way I act like around my normal people, automatically they stereotype me and look at me down by automatically looking at me they stereotype, but once I open my mouth that’s when they take a step back like oh I wasn’t expecting that kind of thing.”

A similar experience was shared in Bunce and King’s (2019) study: “I feel like an imposter, put in an act, my accent changes.” The white voice was also familiar in Osbourne et al. (2023a), and even though this theme seemed to affect international students more because they did not have British accents, home students shared having to put up a white voice too: “My white voice, oh it’s like (puts on voice) oh hi xxx, I’m ok, erm oh yeah I’ll do that for you later…. whereas like my normal voice, I’ll probably throw in a bit of slang in there just subconsciously without even trying”. Thus, it applied to both because they share the superordinate category of ‘Black student.’

As a result, Black students devise strategies, tactics, and approaches to avoid or deal with circumstances in which they are subjected to racism or expect a potential for this. They believed that to be accepted, they needed to conform to the standards of behaviour typically associated with non-Black Minority Ethnic (BME) groups. Essentially, this meant having to change their appearance and actions. For instance, they felt compelled to straighten their hair: “I had to straighten my hair to appear less Black because my natural hair was deemed unprofessional” (Akel 2019). ”Some of us have changed our hair to get involved in the sport” (Inyang and Wright 2022). Other Black students were seen to change their names to English ones (Bunce et al. 2021; Bunce and King 2019).

Furthermore, some Black students felt they had to regulate their Blackness on campus to fit in (Osbourne et al. 2023a) and to dress smartly to dispel perceived scruffy stereotypes (Claridge et al. 2018). Even Black British students who were born and bred in the UK report having their Britishness questioned by their peers. There is suspicion about their nationality (Akel 2019). The Black students were asked questions such as, “How long have you been in this country?” and “Your English is really good” (Akel 2019). In other words, there were questions about whether they were genuinely British: “You’re literally on constant regulation you’re trying to regulate your Blackness and again, like when people are insulting you or whatever, even if it’s on accident or on purpose like you’re still tryna not look like this angry, vivacious person or whatever. Like it’s just constantly down-regulating yourself to make people feel comfortable” (Osbourne et al. 2023b)

A female Black student, realising that other students had to present a moderated version of themselves, chose to be as “Black as she can be” and did not attempt to tone down her Blackness. It made sense to her as a coping mechanism, whereas for others, embracing their Blackness came after other strategies had been attempted. Nonetheless, in Osbourne et al. (2023a), a female student believed that because people like her were not well represented on campus, “it was important to embrace my cultural identity and not take it for granted.”

The experience of adopting white behaviours as a coping mechanism is also noted; for instance in Claridge et al. (2018), some Black male students had to adopt the behaviour of white male students as a coping mechanism. Meanwhile, others, particularly Black women, might consciously become quieter to avoid the “angry Black woman” stereotype, despite legitimate feelings of frustration. This student shared her experience by narrating, ‘‘That angry Black woman stereotype… it really, really annoys me because it’s like sometimes I have a legitimate reason to be upset or angry with what you’re saying and it’s like, oh, there she goes again! And it’s so dismissive of the feelings, and it’s like, what’s the point then?” Also, in Pendleton et al. (2022), a female student shared, “I find that if you don’t come across smiley and happy you come across angry and that angry Black girl stereotype comes out.”

In clinical settings, a Black male student observed that his large stature was useful for physical presence but was counterproductive when he spoke, as his communication was labelled aggressive and poor despite his intentions: “Being male, Black of big stature was useful when male presence was needed in confrontation situations on the ward. It did not work for me when I opened my mouth and was asking questions, I was told I was aggressive, too loud, that my communication and interpersonal skills were poor” (Miller and Nambiar-Greenwood 2022).

Overall, these findings illustrate the various strategies Black students used to navigate and mitigate the impact of racialised treatment in their academic and social environments.

4.8.5. Contribution of Racism/Institutional Factors

Direct/Indirect Racism

Fourteen out of the nineteen articles reviewed highlighted that Black students frequently experience both direct and indirect racism from fellow students and staff. Everyday racism described by Ramamurthy et al. (2023) as “part of the culture,” often goes unchallenged. Those who address such racism are sometimes dismissed as “probably being oversensitive,” reflecting a broader dismissive attitude towards their concerns. In Wong et al. (2021), a participant said, “A lot of other people from white backgrounds just have no idea and would never experience the everyday realities of racial inequalities as lived by minority ethnic people.”

Racism can manifest as overt or covert. For example, racial slurs and discriminatory assumptions about academic abilities are common. Some Black students believed that swear words were glamorised. Participants had experienced racism from students and staff. The constant stress of being confronted with racism (including racial microaggressions), discrimination, and having to survive hostile racist environments at university led to poor academic performance.

Pryce-Miller et al. (2023) documented a student’s frustration with being questioned about their nationality: “Although I was born in the UK, I am always asked how long I have been in the country and the remark that my English is good. They are racist and make so many assumptions.” Osbourne et al. (2021) described how another student faced stereotypes about being “less cerebral,” with others expressing surprise at their academic success, reflecting prejudiced expectations: “It is a thing where people actually expect me to be dumb and so If I get something right, I get ‘oh you’re so much smarter than I thought you were’ and I’m like I don’t know what that means I got into university just like you did.”

Both Black home and international students reported experiencing racism, though their coping strategies differed. Osbourne et al. (2023a) found that Black home students believed that even though they experienced racism like the Black international students, the difference was that they had insider knowledge of how to navigate racism in the UK, for example, “laugh things off”; “ find a more tactful way of saying ok that’s not cool”, unlike the Black international students who were perceived to have greater social freedom and be confrontational about racism. Ramamurthy et al. (2023) recounted a Black student being advised to “grow a thick skin because racism has happened throughout their training” and another participant recanted a harrowing experience of being told they were “overly sensitive” when they challenged the racist acts. Even when participants recounted many incidents of direct and indirect racism, both in learning environments and work placements, they found it difficult to report and challenge such incidents; they described it as a “taboo subject” (Bunce et al. 2021).

It was interesting to see that in some instances, Black Africans suggested a racial hierarchy between themselves (Black Africans) and Black British individuals, those who were born and raised in Britain. Even though they were both Black, the participants believed that they experienced greater marginalisation and oppression as opposed to their Black British African peers.

Moula et al. (2024) highlighted the expectation for Black students to suppress reactions to discrimination to avoid being labelled as “angry Black males.” One student shared, “When you feel discriminated against, you feel like you have to ignore it or laugh it off, but you can’t react because the next thing is, ‘you reacted like every other angry Black male.” This highlights the pressure Black students often face to suppress their reactions to racism, as they fear being stereotyped or judged based on racial biases.

Lack of Black Representation of Staff Member

Black students frequently noted the scarcity of Black role models and staff who resembled them. Inyang and Wright (2022) reported that one student observed the low number of Black staff in institutions serving a diverse student body, and another lamented, “I’m trying to think of Black women I’ve seen in education or as an academic; it’s terrible, isn’t it? I think I met one, 10 years ago.” Akel (2019) noted that many Black students seek support from staff who share their background, believing they would better understand their experiences. Bunce et al. (2021) found that most staff members were non-BME, which contributed to a lack of representation. Wong et al. (2021) emphasised the importance of staff diversity for fostering a sense of belonging, with one participant noting, “If all I see is white male (staff) middle to old-aged, I wouldn’t be encouraged to pursue that degree.”

Moula et al. (2024) further emphasised the need for diverse representation in academia. One student remarked, “It’s not OK to only have Black people in EDI roles. If I don’t see myself as a professor, I’m not going into academia. How am I supposed to know that I am allowed to be a professor?” Another participant shared the impact of seeing a Black tutor: “I went to a tutorial and the person leading it was Black. I was so engaged sitting and listening to someone that looks like me. I realised, all of a sudden, this is what my white counterparts feel like every single day.”

Seemingly Acceptable Racism

This testimony underscores the significance of representation in fostering a sense of belonging and engagement among Black students, as they see themselves reflected in the academic environment.

A culture of racism that goes unchallenged can render it seemingly acceptable within certain environments. Five of the nineteen articles documented how racist language and behaviour became normalised. Participants felt that racist language went from something they did not often hear to something they perceived as being commonplace and part of everyday life (Osbourne et al. 2021, 2023a; Taylor 2021; Akel 2019).

In Osbourne et al. (2023b), a student described their experience with flatmates who used the ‘N word’ in casual contexts, often under the guise of quoting or referencing: “They tried to, one of them as an insult, the others would just say it like in songs, say it in reference to stuff. But it’s always like a quotation mark thing like ‘oh I’m not saying it; I’m just referencing that he said it’ or ‘oh it was in a song.’”

Unfortunately, this sort of thing was not an isolated circumstance. Several examples were presented of the glamorisation and the unrestrained desire of their white peers to be allowed to make use of the ‘N’ word. Some Black students in the analysed articles described white participants calling each other the ‘N’ word as a form of greeting, while others openly debated who should have permission to use the word. This placed Black students in an unusually uncomfortable position. Black students felt they were entering a racially charged environment and faced some discomfort. When they confronted those using racist racial language, they played down experiences of racism as light-hearted jokes and ‘banter’ (Akel 2019). This term, as well as other racist and abusive sobriquets, is hugely triggering for many who hear it. As part of the visible majority, white students arguably have the power to decide what is appropriate and acceptable (Shelton et al. 2006), hence why they downplayed these acts and relegated them to ‘banter’. This issue extended to broader social environments where Black students faced discomfort and the burden of challenging casual racism. In one account from Akel (2019), a student witnessed a white peer yelling the ‘N word’ in a public space, with bystanders showing little reaction: “There was a white guy who was yelling the N word at the top of his lungs and this white girl was right next to him and was just like, had a very tortured expression. But he’s really going at it, just like in the middle of a hall, and there’s tons of people walking around. It’s really awful, actually.” This illustrated how pervasive and unrestrained racism can create a hostile environment, where racist acts are minimised or ignored by those not directly affected.

5. Discussion

This systematic review evaluated the educational experiences of Black students in UK HEIs, highlighting key challenges such as academic scrutiny, mental health issues, institutional racism, and lack of representation while acknowledging shared and distinct experiences among Black international and British students. A lack of autonomy (survival strategy) and other contributions of institutional factors, including direct and indirect racism, a lack of representation among staff members, and seemingly acceptable racism, were also included.

The review highlights that Black students often face heightened scrutiny regarding their academic abilities. Despite their competence, they encounter stereotypes and lower expectations, leading to experiences of being underestimated. As Osbourne et al. (2021) noted, Black students are sometimes met with surprise and condescension when they excel academically, reflecting the pervasive “twice as hard” rule, which demands that Black students work significantly harder to prove their competence.

The findings demonstrated that Black international students had to acclimatise to a new society, modify their accents, dress differently, and straighten their afro hair. Interestingly, some reported adopting a white voice (Osbourne et al. 2023a; Akel 2019; Bunce and King 2019). This change influenced more international students than home students. This distinction is vital because CRT posits various levels of racism that a Black person may confront that are based on accent, immigration status, surname, and phenotype. In other words, such modifications are coping strategies in response to systemic racism.

However, the caveat is that Black international students were not the only ones who had to straighten their afro hair or adopt a white voice despite already possessing a British accent. Thus, despite being British, their shared ethnicity and superordinate category of “Black students” did not wholly exclude them from any racial discrimination or from having to conform (Osbourne et al. 2023a).

The impact of racism on mental health is significant. The trauma of discrimination led to mental fatigue, characterised by heightened anxiety, and diminished cognitive capacities, which can adversely affect academic performance.

The impact of racism on mental health among Black students is profound, often leading to trauma, heightened anxiety, and mental fatigue, which collectively impair cognitive capacities and academic performance (Andrews 2016). These psychological effects create a vicious cycle, as the stress and emotional toll of discrimination reduce students’ ability to engage effectively in their studies, further compromising their academic outcomes. Addressing these systemic issues is crucial to supporting the mental well-being and educational success of Black students.

Racism, whether direct or indirect, has a profound impact on Black students. The systematic review identified instances of both overt racism, such as racial slurs, and covert microaggressions. The concept of “seemingly acceptable racism” is particularly concerning, as it illustrates how racist behaviours can become normalised and dismissed as “banter” (Osbourne et al. 2021, 2023a, 2023b; Akel 2019). This normalisation of racism in academic settings creates a hostile environment for Black students.

Black students also often narrated feeling that their experiences had been dismissed, a troubling trend that reflects broader patterns of racial inequality. This dismissal of Black students’ experiences aligns with Bell’s analysis of racial standing, noting that not only are Black individuals’ complaints discounted, but they are also perceived as fewer effective witnesses compared to their white counterparts, who belong to the oppressor class. This dismissal may also serve to silence Black voices, further marginalising them within academic spaces.

Additionally, when some students talked about their racist experiences, they were urged to “toughen up because racism had occurred throughout their training,” effectively locating problems in individuals’ responses rather than the actual anomalous experience. This serves to highlight one of the tenets of CRT, which is the notion of ordinariness, which asserts that racism is a part of Black people’s daily lives (Delgado et al. 2023). Moreover, because it is so ingrained in our societal order, it appears normal and natural to people (Ladson-Billings 1998). Some students felt they received lesser marks than they felt their work was worth, especially when compared with their white peers, because of their ethnicity, and often, after successful appeals, their grades were reviewed and increased.

The lack of representation of Black lecturers at the highest levels of academia, particularly in research-intensive universities, has an epistemic impact on future generations of scholars who do not see themselves represented in academia (Fox Tree and Vaid 2022). However, because there is a dearth of representation of Black staff members in positions of authority, they face added emotional labour and pressure to be the only support system available, especially in situations when they have no influence (Akel 2019).

Belonging means feeling included and validated as an individual in a group. Belonging promotes mental well-being, academic success, and student retention (Inyang and Wright 2022). Some students felt like they belonged in HE, while others did not. Students’ ideas of what creates a sense of belonging could influence their feelings, and based on the studies examined, two categories that influence a sense of belonging were internal factors (adapting to one’s environment) and external factors (forming an inclusive atmosphere). The OFS (2019) asserts that institutions must acknowledge the lived realities of Black and other minority ethnic students and strive to comprehend the cultural barriers that they encounter continuously.

The phrase ‘awarding gap’ acknowledges a diversity of factors that affect student performances and how institutional structures and racism can impact them (Jankowski 2020). The research predominantly highlighted the adverse experiences faced by Black students. These studies consistently found that students who experienced racism or racist acts tended to perform worse compared to their white peers, who did not encounter similar experiences. Many of these experiences were cumulative and impacted their academic performance both directly and indirectly. These negative experiences were often compounded over time, affecting students’ academic outcomes through various mechanisms. Additionally, the findings identified potential protective factors that could mitigate the effects of adversity. For example, fostering a sense of belonging and enhancing students’ self-esteem as capable learners are crucial strategies that can help buffer against the negative impact of racial adversity.

Therefore, it is essential to develop strategies that not only address the adverse experiences but also bolster the protective factors. This holistic approach is key to supporting Black students in overcoming barriers and achieving academic success.

A critical finding across the reviewed literature was the strong correlation between experiences of racism and poorer academic performance among Black and minority ethnic students (Osbourne et al. 2021; Pryce-Miller et al. 2023; Wong et al. 2021). Although the Black awarding gap was not always explicitly mentioned, this systematic review suggested that findings can aggregate together to help explain the awarding gap. Although being differently configured for each student, they contribute to a persuasive multi-factorial explanation overall.

The findings revealed predominantly adverse experiences, many of which were cumulative and affected academic performance both directly and indirectly. These negative experiences, often linked to racism, biassed assessments, and a Eurocentric curriculum, contribute significantly to the sense of exclusion felt by these students. However, the review also identified protective factors, such as fostering a sense of belonging and enhancing students’ self-esteem, which can mitigate the negative impacts and support academic success. Taken together, the findings suggest a multi-factorial set of experiences and institutional barriers that may contribute to the awarding gap, offering insight into the challenges faced by Black students and pointing to potential strategies for promoting more equitable academic outcomes.

Furthermore, this systematic review highlighted the institutional challenges that shaped the participants’ experiences. Many participants believed their African or Caribbean descent caused them to receive lower marks than they deserved. While multiple factors could have explained these grade discrepancies, the students suspected racial bias. This finding was critical, as it aligned with other reports of students feeling marked down because of their ethnicity. The perception that their ethnic background influenced how they were assessed academically led some students to lose faith in the educational system, believing it impacted how their intelligence and abilities were perceived within the learning environment. This loss of trust further exacerbated the already existing gaps in academic achievement.

Additionally, students often felt that the curriculum was Eurocentric, presenting predominantly Western perspectives and knowledge while excluding contributions from non-white cultures. Black and Brown students were particularly sensitive to this, noting that their white peers seemed unaware of these biases. This awareness of a Eurocentric curriculum further alienated minority students, as they felt marginalised in an academic environment that failed to recognise or validate their cultural backgrounds. The narrow focus on Western perspectives heightened their sense of exclusion and made them perceive the institution as unsupportive and unreflective of their identities or experiences. This and concerns about biassed marking deepened their disillusionment with the educational system.

Additionally, they believed that because of the institutional racism that perpetuates negative stereotypes, they had to shed some of their Black identity. For example, they thought that their ethnic background carried a lot of negative connotations, so even though they wanted to be vocal and energetic, they had to be quiet and not be perceived as loud and aggressive. Also, they felt they had to change their accent or straighten their afro hair to avoid the perception of unprofessionalism. In summary, all their experiences at university and during work placements impacted their academic achievement.

Not all the experiences, though, were terrifying and unpleasant. A few participants shared their positive experiences, believing they could blend in at university without hiding their Black identity or changing anything about themselves because they felt they belonged at university and that their non-BME peers understood them. They were also happy that their non-Black professors made them feel at ease (Osbourne et al. 2023a; Inyang and Wright 2022; Bunce et al. 2021; Bunce and King 2019).

Addressing Inequalities: Potential Strategies and Interventions

While much of the literature focused on the systemic barriers and racialized experiences of Black students in UK higher education, several studies also proposed tangible strategies to address these inequalities. Key interventions included the implementation of anti-racist and decolonised curricula, the recruitment and retention of Black academic staff to improve representation, and the establishment of culturally responsive mentorship programmes. Additionally, staff training on racial literacy and unconscious bias was frequently recommended to challenge deficit-based thinking and institutional complacency. Some papers highlighted the importance of creating safe spaces and peer-led networks to foster belonging and psychological safety for Black students. These strategies demonstrate not only the challenges identified through critical race research but also the possibilities for resistance, transformation, and systemic change within the higher education sector.

6. Materials and Methods

The systematic review was conducted using seven comprehensive databases, Academic Search Complete, Education Abstracts, PsycINFO, Race Relations Abstracts, Web of Science, Scopus, and SocINDEX, as outlined in Table 1. The search strategy focused on studies published between 2012 and 2024, with additional filters for peer-reviewed, qualitative research.

For inclusion and exclusion criteria, refer to Table 2 as before.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to determine study eligibility are summarised in Table 2.

7. Conclusions

Understanding the experiences of Black students in HE requires a close examination of institutional variables. The evidence presented underscored that Black students frequently encountered a range of negative experiences, including racism, discrimination, and microaggressions, which significantly impacted their mental health and academic performance.

The documented link between racism and mental health issues among Black students highlighted a pressing concern. Studies consistently revealed that experiences of racism and discrimination contributed significantly to heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among Black students. These detrimental encounters not only impacted their overall well-being but also hindered their academic progress, thereby exacerbating the Black awarding gap.

It is advised that university staff members should receive training to effectively support students and signpost to staff capable of addressing the counselling needs of Black students. Additionally, educational institutions, including practice placements, must acknowledge and address the hostile experiences faced by Black students. These institutions have a responsibility and the authority to combat all forms of racial discrimination.

A critical examination of institutional practices is necessary to ensure that Black students are not neglected, marginalised, or silenced. More research is warranted, particularly concerning the various survival or adaptation strategies adopted by Black students. It is essential to determine whether these strategies involve genuine adaptation or merely assimilation within the university environment.

The Ph.D. research enriches the existing literature by delving deeper into the factors influencing Black students as they navigate their HE journeys within the overarching framework of the perceived Black awarding gap. Through these narratives, the study provided valuable insights that informed a critical assessment of the appropriateness and effectiveness of interventions to address this gap.

Moreover, by shedding light on the experiences of Black students, this research empowers students to navigate the complex social systems inherent in the HE landscapes. Ultimately, the study enhances Black students’ experiences within the HE system.

The findings of this review underscore how university environments can often be experienced as hostile by Black students—for example, being perceived as “loud” for expressing themselves or feeling pressure to alter their identity to fit dominant norms. By bringing attention to these everyday racialised experiences, this review not only highlights the depth of the problem but also contributes to a broader understanding of how systemic inequality is reproduced in higher education settings. Such insights are essential for developing effective, anti-racist interventions and informing institutional policy and practice. These findings align with broader UK efforts to address racial inequalities in higher education, such as initiatives by the Office for Students and Advance HE’s Race Equality Charter, which aim to reduce awarding gaps and improve institutional equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation V.I., M.M., J.P.W. and A.C.; Methodology V.I., M.M., J.P.W. and A.C.; Formal analysis V.I. and M.M.; Data curation V.I.; writing original draft preparation V.I.; writing review and editing V.I., M.M., J.P.W. and A.C.; supervision M.M., J.P.W. and A.C.; funding acquisition J.P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Central Lancashire.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Lancashire Ethics Committee BAHSS2 0275.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This is a systematic literature review as such there is no data from participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BAME | Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic |

| BME | Black and Minority Ethnic |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| CRT | Critical Race Theory |

| HE | Higher Education |

| OFS | Office For Students |

| UCLAN | University of Central Lancashire |

References

- Akel, Sofia. 2019. Insider-Outsider: The Role of Race in Shaping the Experiences of Black and Minority Ethnic Students. London: Goldsmiths, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Kehinde. 2016. Resisting Racism: Race, Inequality, and the Black Supplementary School Movement. London: Trentham Books. [Google Scholar]

- Arday, Jason, Charlotte Branchu, and Vikki Boliver. 2022. What do we know about Black and minority ethnic (BME) participation in UK higher education? Social Policy and Society 21: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, Louise, and Naomi King. 2019. Experiences of autonomy support in learning and teaching among black and minority ethnic students at university. Psychology of Education Review 43: 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, Louise, Naomi King, Sinitta Saran, and Nabeela Talib. 2021. Experiences of black and minority ethnic (BME) students in higher education: Applying self-determination theory to understand the BME attainment gap. Studies in Higher Education 46: 534–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, Hugh, Khadija Stone, and Michael Ussher. 2018. The ethnicity attainment gap among medical and biomedical science students: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education 18: 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2018. CASP Qualitative Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/qualitative-studies-checklist/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Delgado, Richard, Jean Stefancic, and A. Harris. 2023. Critical Race Theory, 4th ed. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox Tree, Jean E., and Jyotsna Vaid. 2022. Why so Few, Still? Challenges to Attracting, Advancing, and Keeping Women Faculty of Colour in Academia. Frontiers in Sociology 6: 792198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inyang, Deborah, and Jacob Wright. 2022. Lived experiences of Black women pursuing STEM in UK higher education. The Biochemist 44: 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, G. S. 2020. The ‘Race’ Awarding Gap: What can be done? Psychology of Women Section Review 3. Available online: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/6782/1/TheRaceAwardingGapAM-JANKOWSKI.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1998. Just what is critical race theory and what is it doing in a nice field like education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 11: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marandure, Blessing N., Jess Hall, and Saima Noreen. 2024. ‘… They’re talking to you as if they’re kind of dumbing it down’: A thematic analysis of Black students’ perceived reasons for the university awarding gap. British Educational Research Journal 50: 1172–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, Orlagh, and Eileen Pollard. 2023. ‘To teach in varied communities not only our paradigms must shift but also the way we think, write, speak’ (hooks, 1994): Creating Resources to Address the BAME Awarding Gap. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. Available online: https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/926/710 (accessed on 12 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Miller, Eula, and Gayatri Nambiar-Greenwood. 2022. Exploring the lived experience of student nurses’ perspective of racism within education and clinical practice: Utilising the flipped classroom. Nurse Education Today 119: 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moula, Zoe, Albertine Zanting, and Sonia Kumar. 2024. ‘I sound different, I look different, I am different’: Protecting and promoting the sense of authenticity of ethnically minoritised medical students. Clinical Teacher 21: e13750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, Lorelli S., Jill M. Norris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules. 2017. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OFS. 2019. Understanding and Overcoming the Challenges of Targeting Students from Under-Represented and Disadvantaged Ethnic Backgrounds. Available online: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/d21cb263-526d-401c-bc74-299c748e9ecd/ethnicity-targeting-research-report.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Osbourne, Lateesha, Amena Amer, Leda Blackwood, and Julie Barnett. 2023a. ‘I’m Going Home to Breathe and I’m Coming Back Here to Just Hold My Head Above the Water’: Black Students’ Strategies for Navigating a Predominantly White UK University. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 11: 501–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osbourne, Lateesha, Julie Barnett, and Leda Blackwood. 2021. You never feel so Black as when you’re contrasted against a White background”: Black students’ experiences at a predominantly White institution in the UK. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 31: 383–95. [Google Scholar]

- Osbourne, Lateesha, Julie Barnett, and Leda Blackwood. 2023b. Black students’ experiences of “acceptable” racism at a UK university. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 33: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Kwarteng, Louise. 2021. ‘Studying in this England is wahala (trouble)’: Analysing the experiences of West African students in a UK higher education institution. Studies in Higher Education 46: 2405–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, Arsenio. 2017. Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 10: 233–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, John, Claire Clews, and Aimee Cecile. 2022. The experiences of black, Asian and minority ethnic student midwives at a UK university. British Journal of Midwifery 30: 270–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponterotto, Joseph G. 2006. Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept thick description. The Qualitative Report 11: 538–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce-Miller, Maxine, E. Bliss, A. Airey, A. Garvey, and C. R. Pennington. 2023. The lived experiences of racial bias for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic students in practice: A hermeneutic phenomenological study. Nurse Education in Practice 66: 103532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, Anandi, Sadiq Bhanbhro, Faye Bruce, and Freya Collier-Sewell. 2023. Racialised experiences of Black and Brown nurses and midwives in UK health education: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today 126: 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, J. Nichole, Jennifer A. Richeson, Jessica Salvatore, and Diana M. Hill. 2006. Silence is not golden: The intrapersonal consequences of not confronting prejudice. In Stigma and Group Inequality. Hove: Psychology Press, pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, Nkasi, Y. Yalipende, N. C. Byrom, S. L. Hatch, and H. Lempp. 2022. Mental health and mental well-being of Black students at UK universities: A review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 12: e050720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Louise. 2021. Seeking Equality of Educational Outcomes for Black Students: A Personal Account. Psychology of Education Review 45: 4–16. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1316951&site=ehost-live (accessed on 20 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, James, and Angela Harden. 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Billy, R. Elmorally, M. Copsey-Blake, E. Highwood, and J. Singarayer. 2021. Is race still relevant? Student perceptions and experiences of racism in higher education. Cambridge Journal of Education 51: 359–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewolde, Solomon. 2022. ‘Race’ and Academic Performance in International Higher Education: Black Africans in the U.K. Journal of Comparative and International Higher Education 14: 211–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]