Jewish Presence in the Land of Israel in the 19th Century: Insights from the Montefiore Censuses

Abstract

1. Introduction

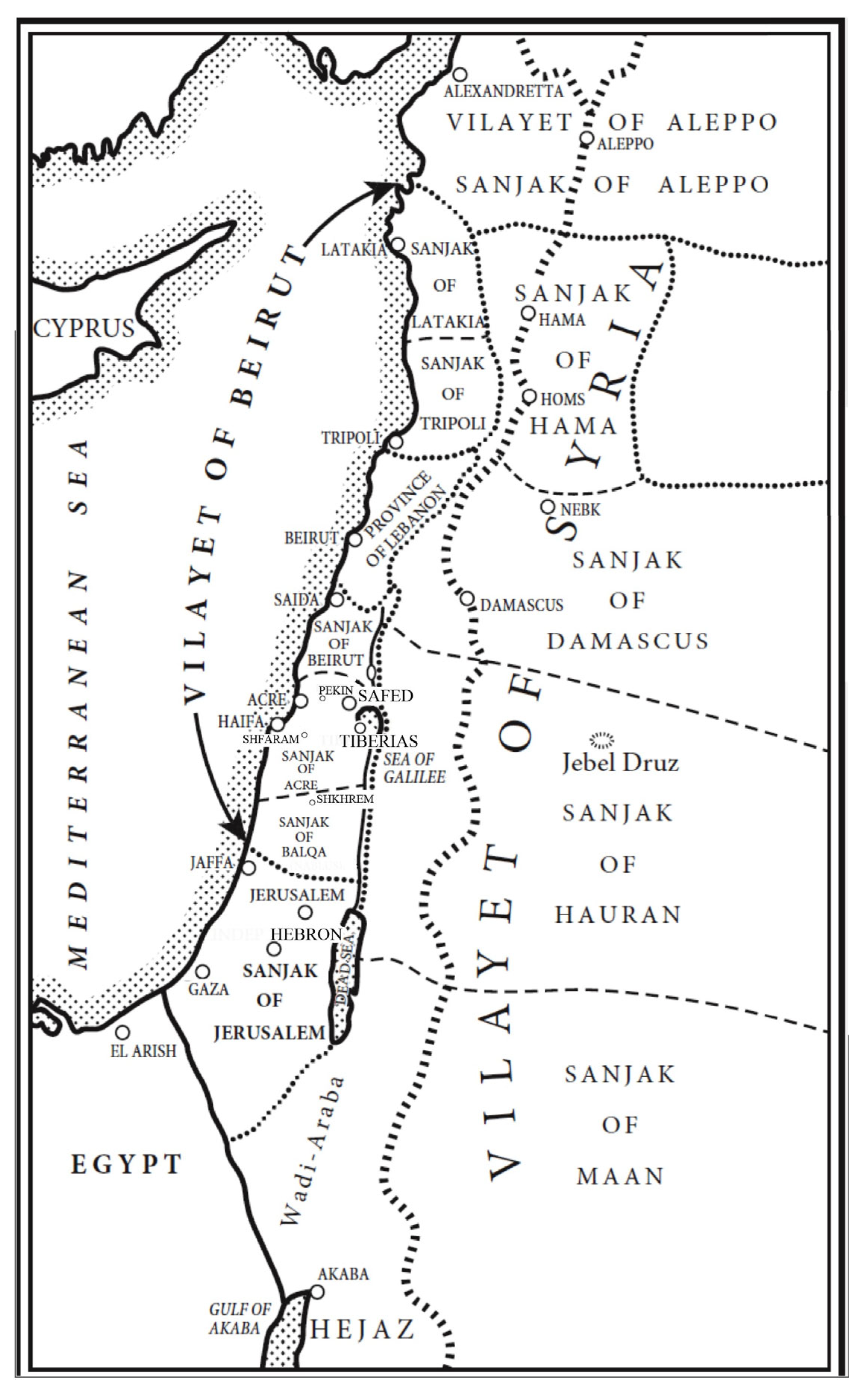

1.1. Early Population Patterns in Palestine/the Land of Israel

1.2. Sir Moses Montefiore

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Censuses

- Year of the census.

- City of residence.

- Kolel: the community in which the family lived. The type of community (i.e., Ashkenazi or Sephardi) was reported. Of note, in Montefiore censuses, all non-Ashkenazi communities were grouped under Sephardim.

- ID number of the family within a census and ID number of each individuals.

- For each individual living under the same roof, the following was reported:

- ○

- Name: given name and surname;

- ○

- Gender;

- ○

- Family status (single, married, orphan, widow, etc.);

- ○

- City and country of origin: the city reported may have been a person’s last place of residence before coming to the Land of Israel, rather than the actual place of birth (The Montefiore Endowment n.d.);

- ○

- Year of arrival in the Land of Israel: allowing for estimation of the age of arrival in the Land of Israel;

- ○

- Age: allowing for estimation of year of birth;

- Occupation: reported for the HH, rarely for other family members.

- Economic status: mainly possessions of the HH.

- Note: the censuses generally provide additional information on the socio-economic status of the HH and the family.

2.2. Analysis of the Data

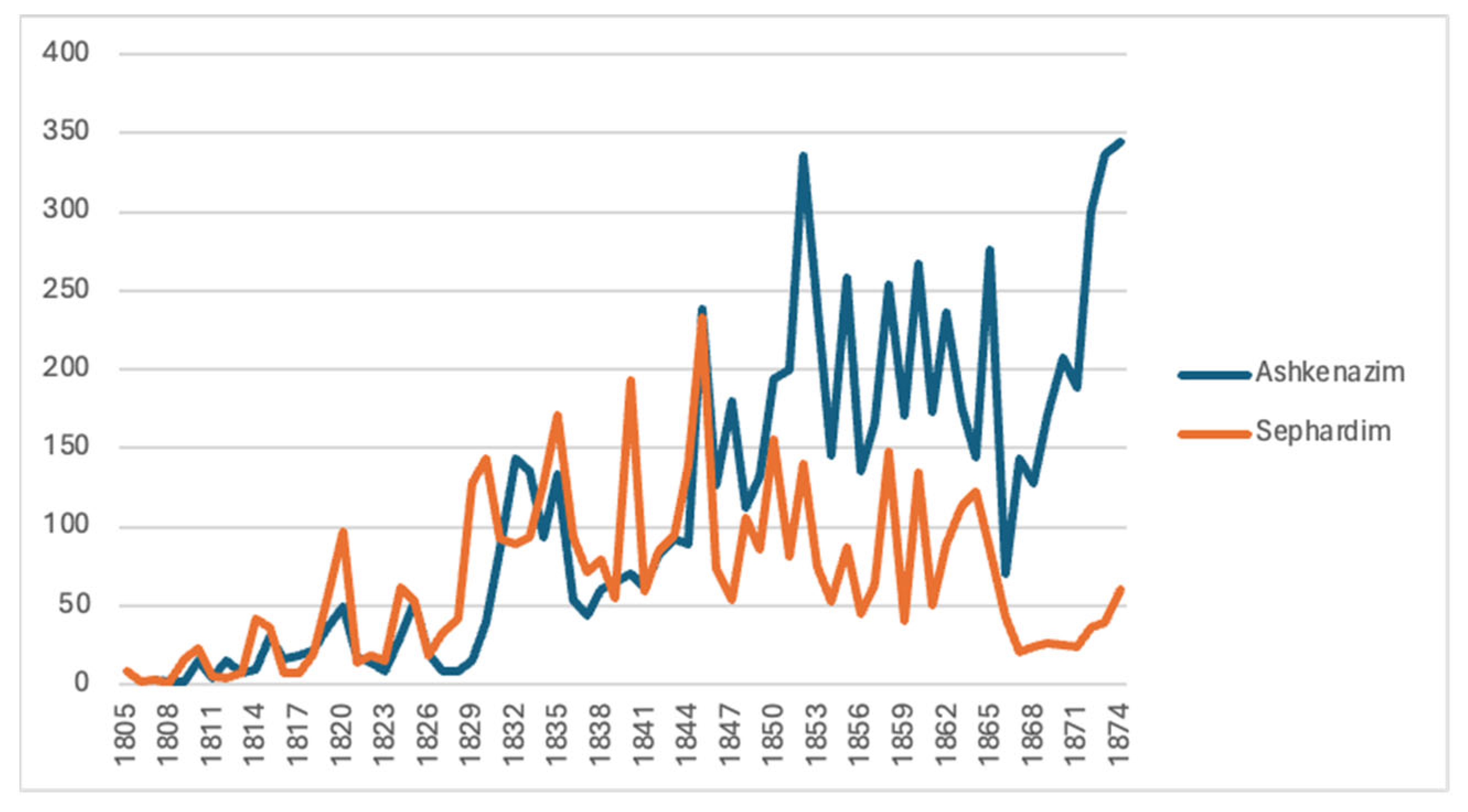

2.2.1. Ashkenazi and Sephardi Communities

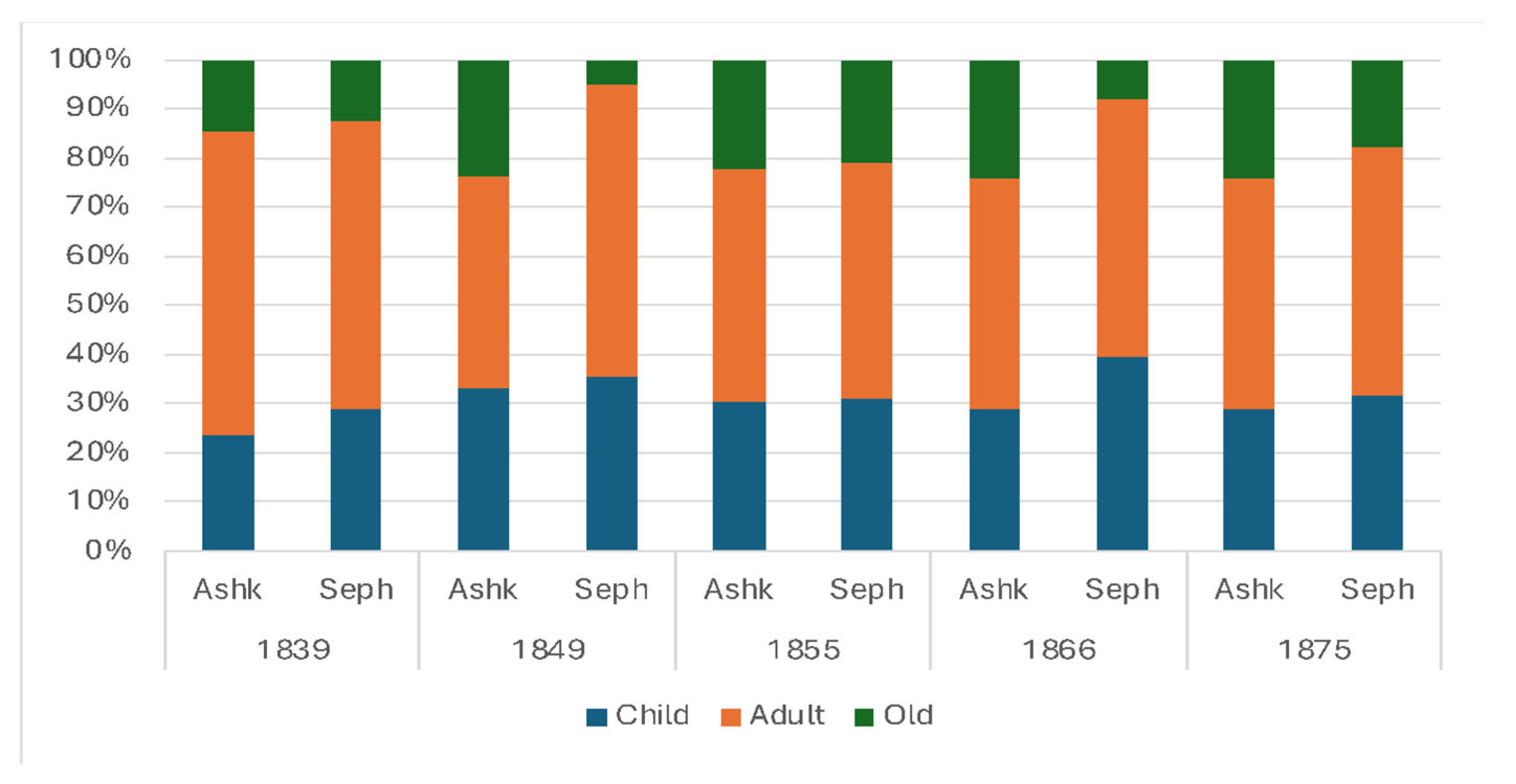

2.2.2. Age

- Child: individuals aged less than 15 years old or listed as “child” in the censuses;

- Adult: individuals aged between 15 and 49 years old or listed as “single” “married” or “widow”, when age was not reported;

- Old: individuals aged more than 50 years old or when “date of arrival” or a mention in “note” gave an indication that age was more than 50 years old.

2.2.3. Occupations

- Intellectual occupation: religious occupation, students, clerical work, education, community service, health and medicine, public officials, art and other liberal professions;

- Physical occupation: domestic services, craftsmen and small jobs, transport and communication (donkey drivers), other industries (workers);

- Business: building industry, commerce, mechanical industry, wood manufacture, printing and stationery industries, financial services;

- Clothing: clothing and millinery industries, leather and textile industries;

- Food industry;

- Persons with no occupation and dependents.

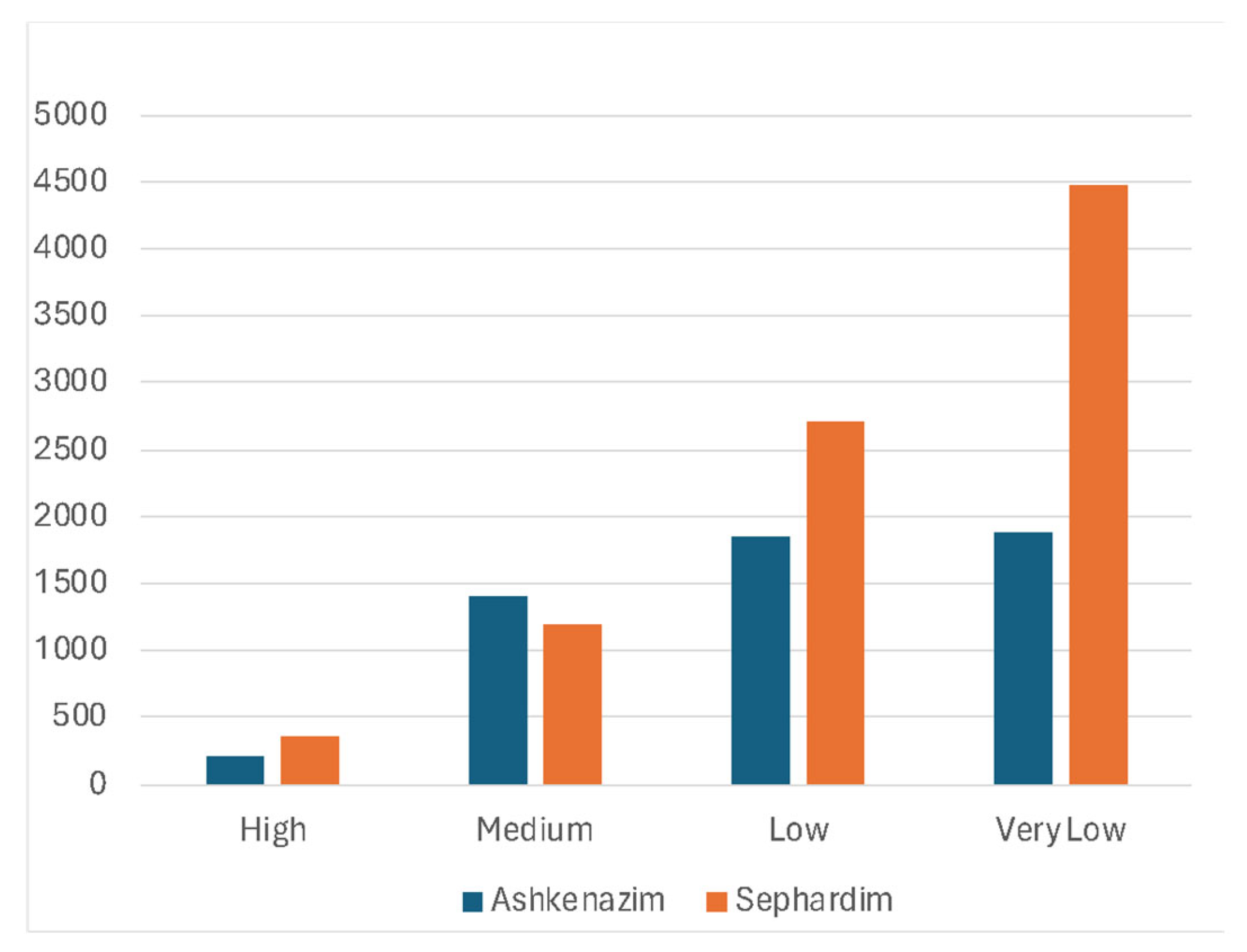

2.2.4. Socio-Economic Status

- High: income or possessions of HH more than 10,000 Grushs;

- Medium: income or possessions of HH from 3000 to 10,000 Grushs;

- Low: income or possessions of HH between 2000 and 3000 Grushs or when it is mentioned in the note that the family is needy despite apparent correct income;

- Very low: income or possessions of HH below 2000 Grushs or when “very poor” or “destitute” is mentioned in “notes”.

2.2.5. Continuity of Residence and Duration of Stay

2.2.6. Waves of Immigration

3. Results

3.1. Number of Entries and Quality of the Data

3.2. Population and Demography

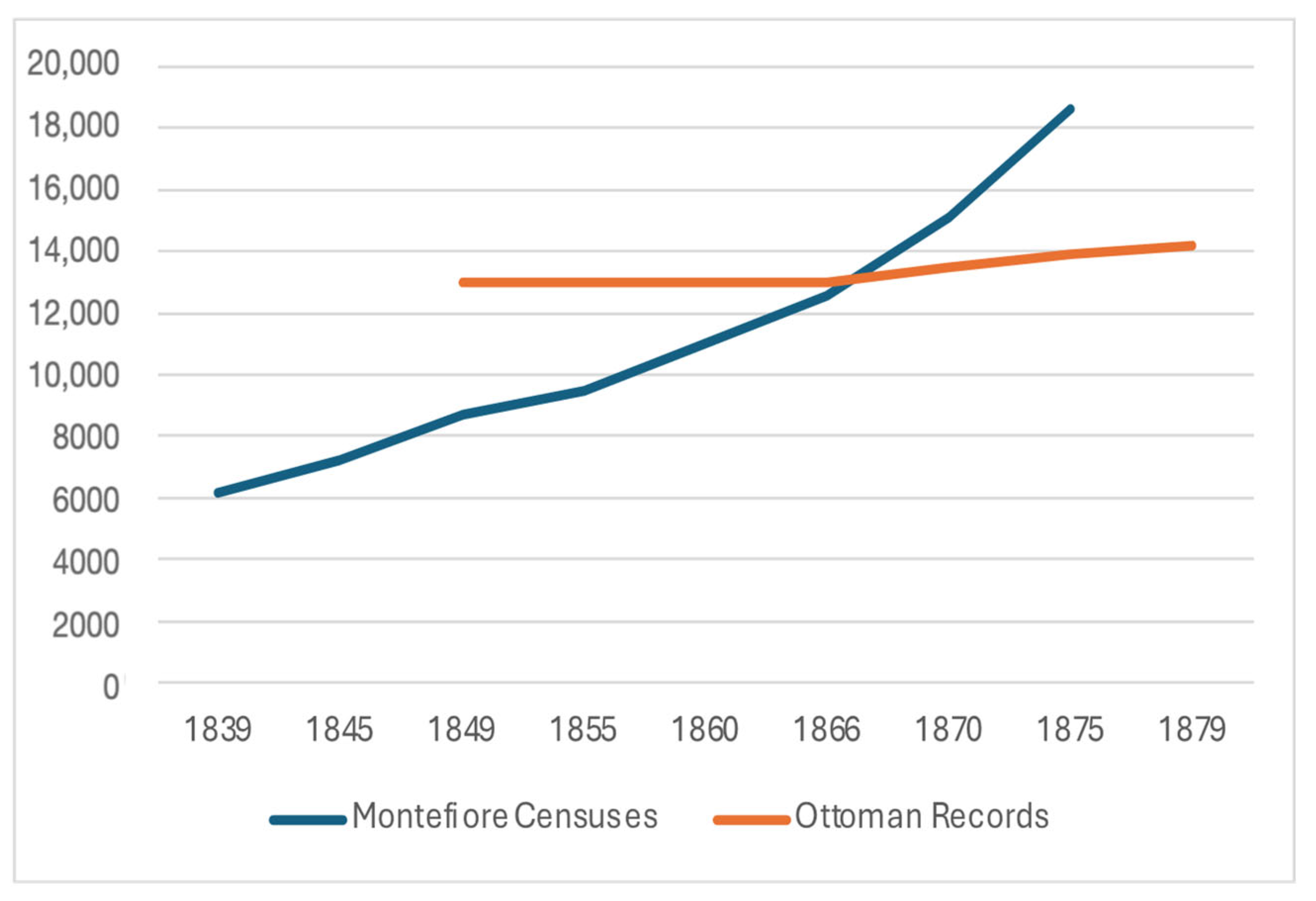

3.2.1. Population Reported in Montefiore Censuses

3.2.2. Comparison with Previous Records and Censuses

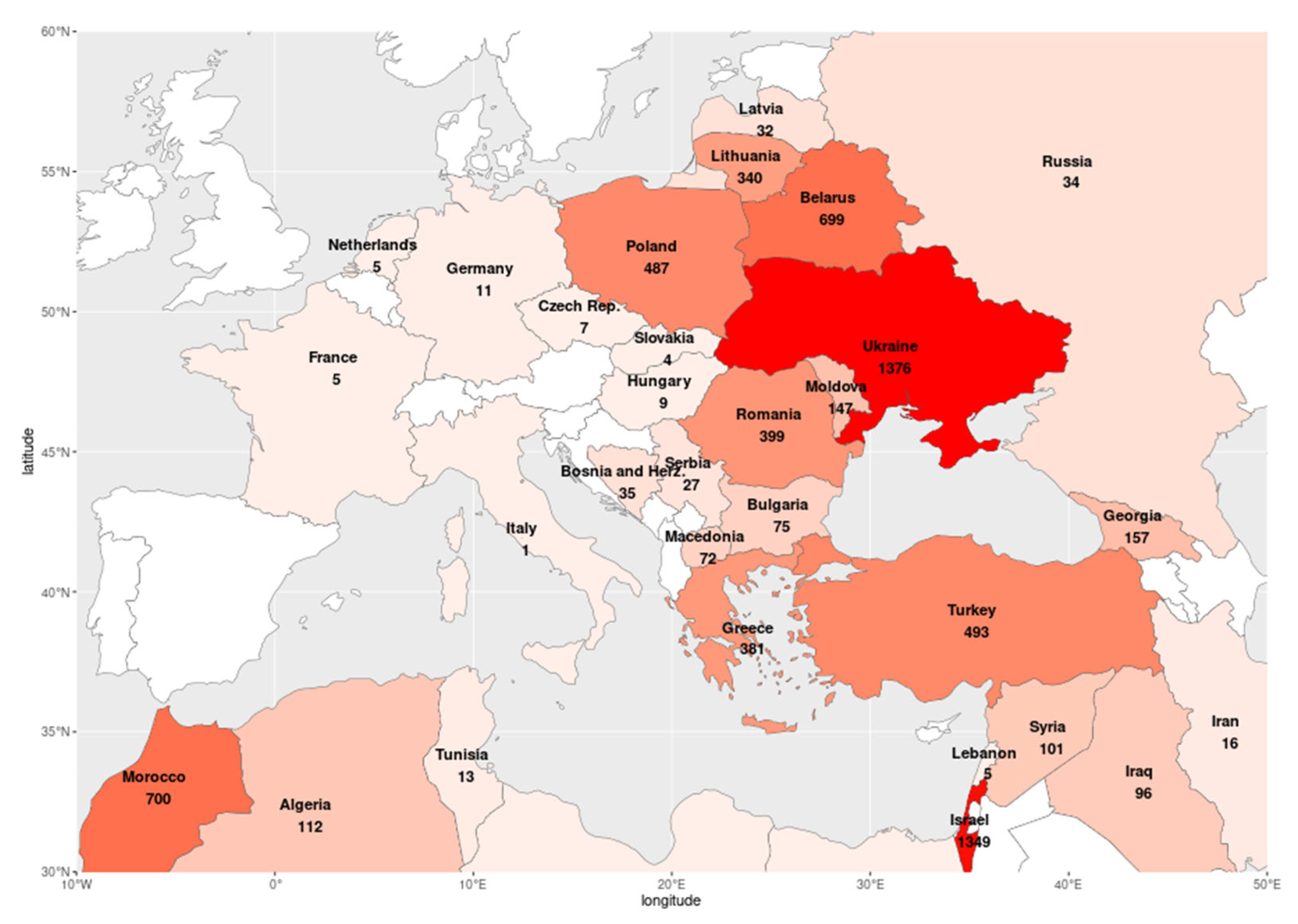

3.2.3. Geographic Distribution of Places of Birth

3.2.4. Continuity of Residence in the Land of Israel

3.2.5. Duration of Stay in the Land of Israel

3.2.6. Retrospective Insights on Jewish Population Size

3.3. Demographics

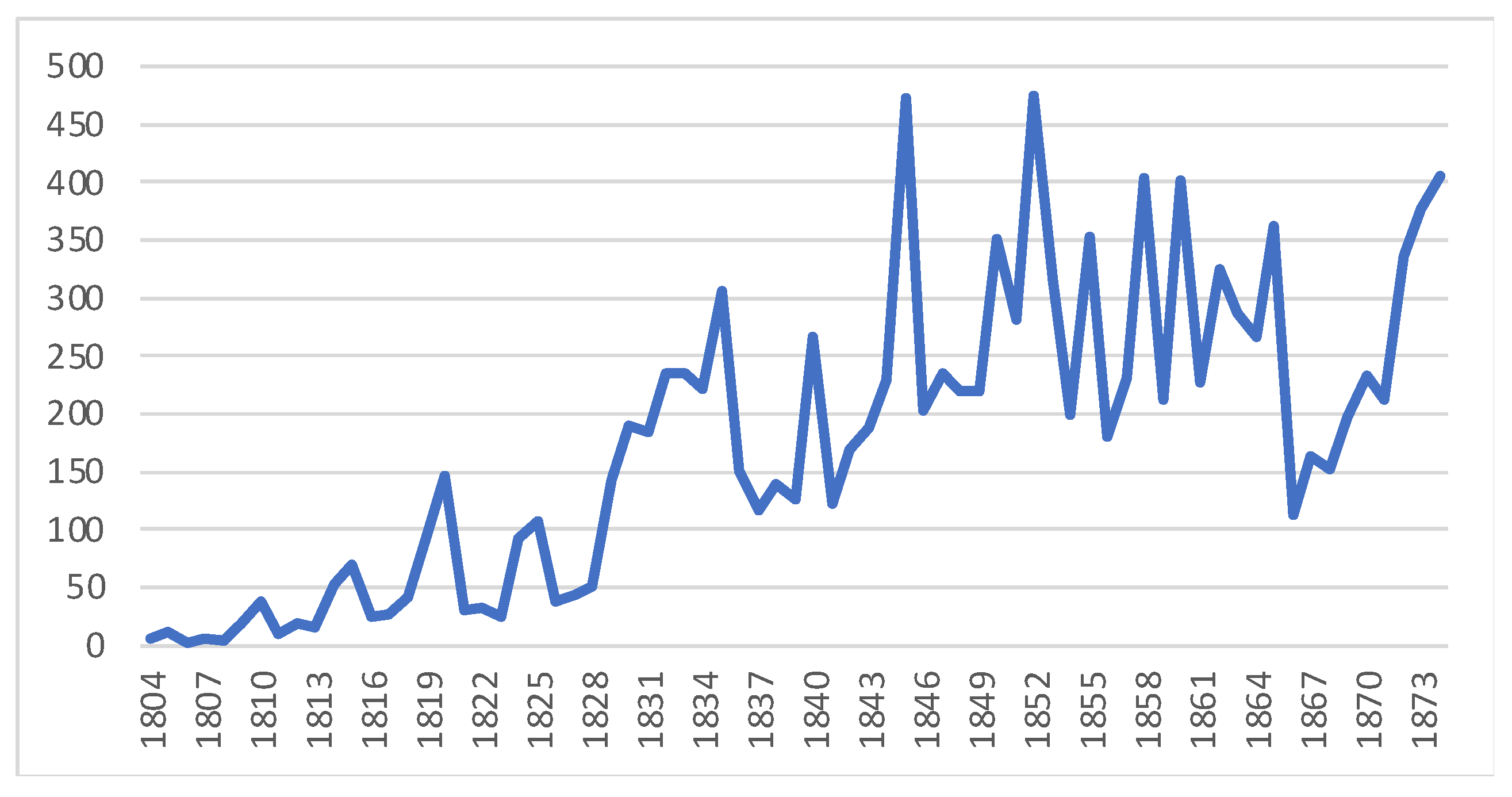

3.3.1. Jewish Population Size

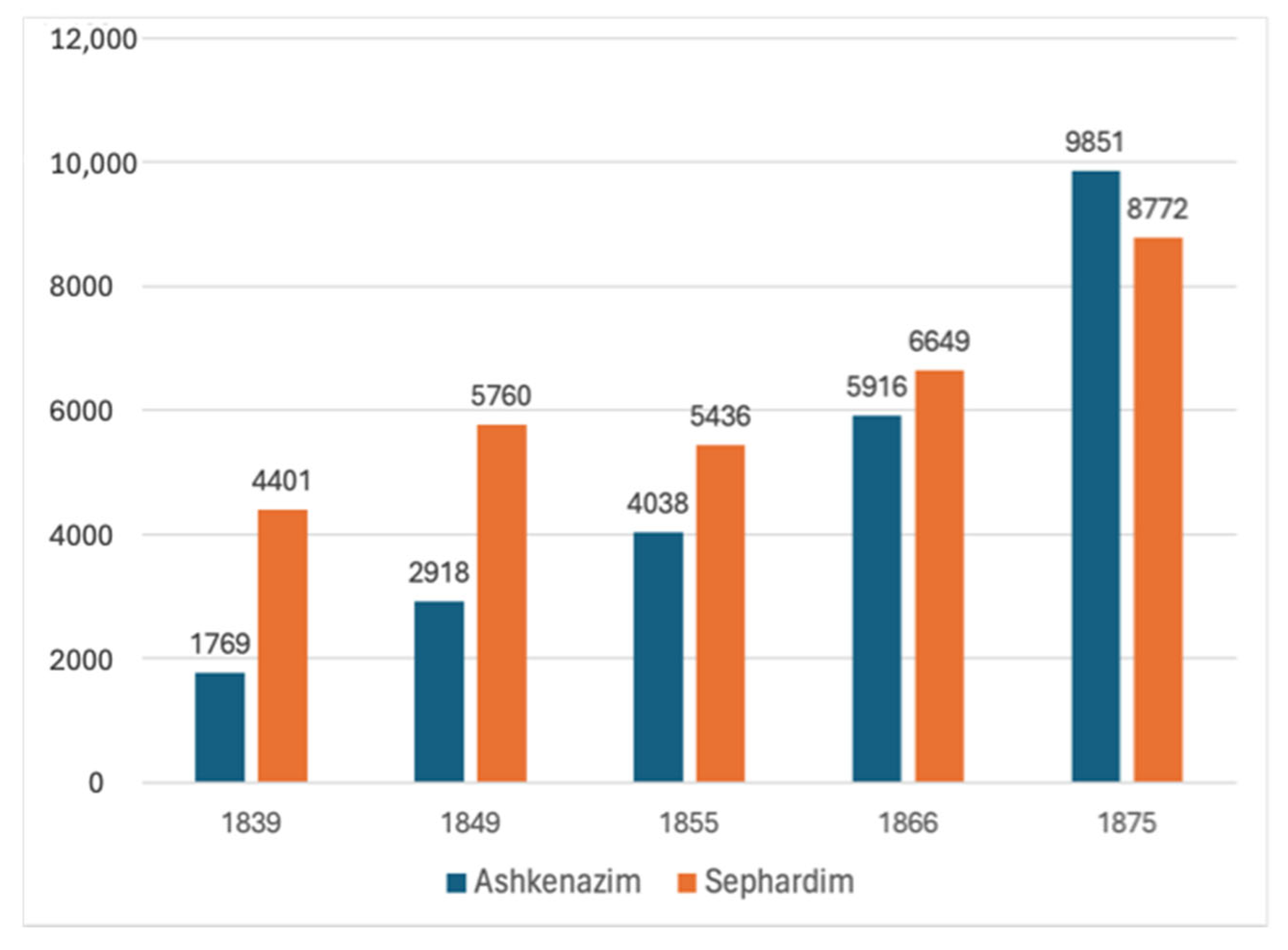

3.3.2. Number of Ashkenazim and Sephardim per Census Year

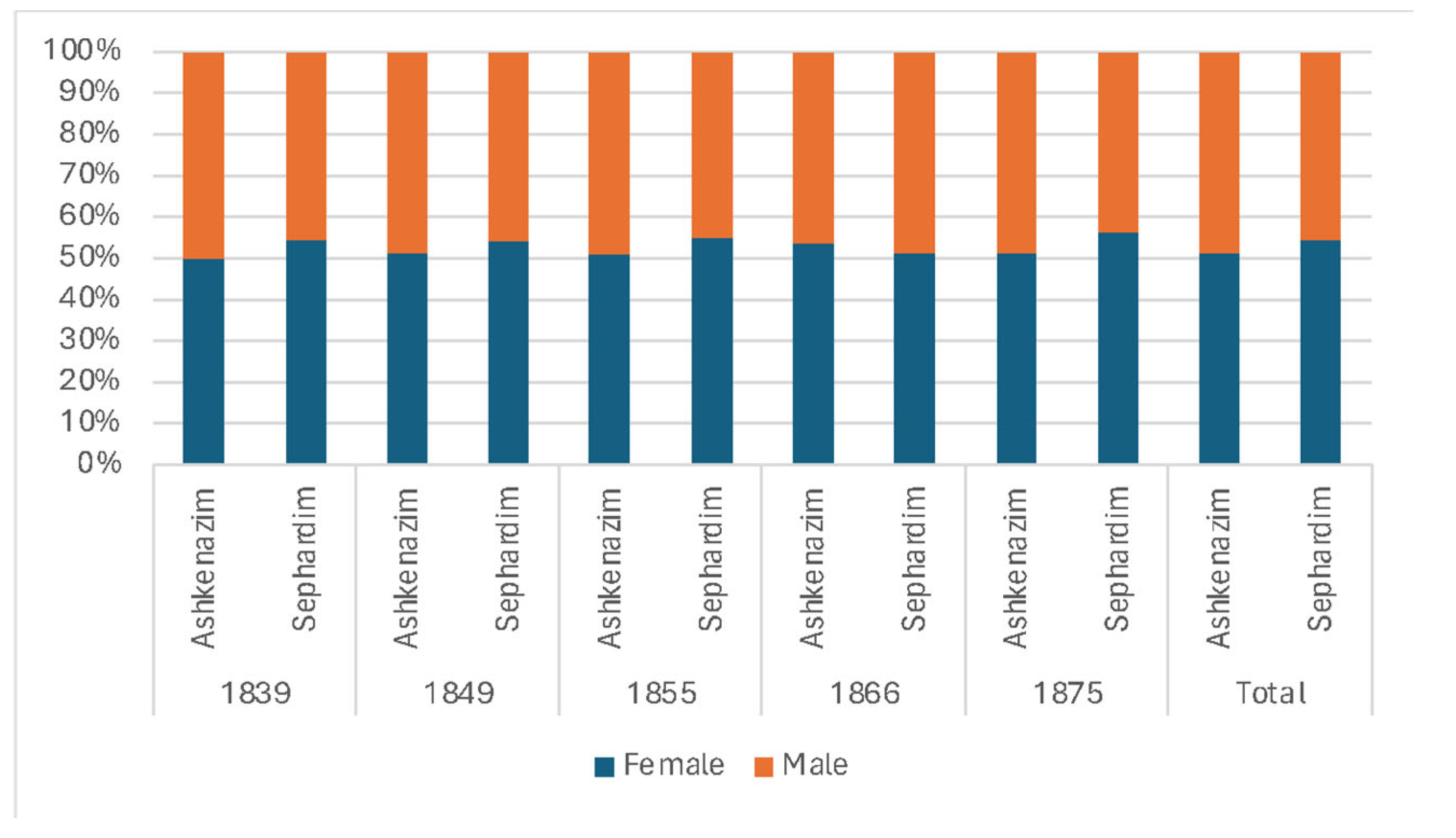

3.3.3. Gender

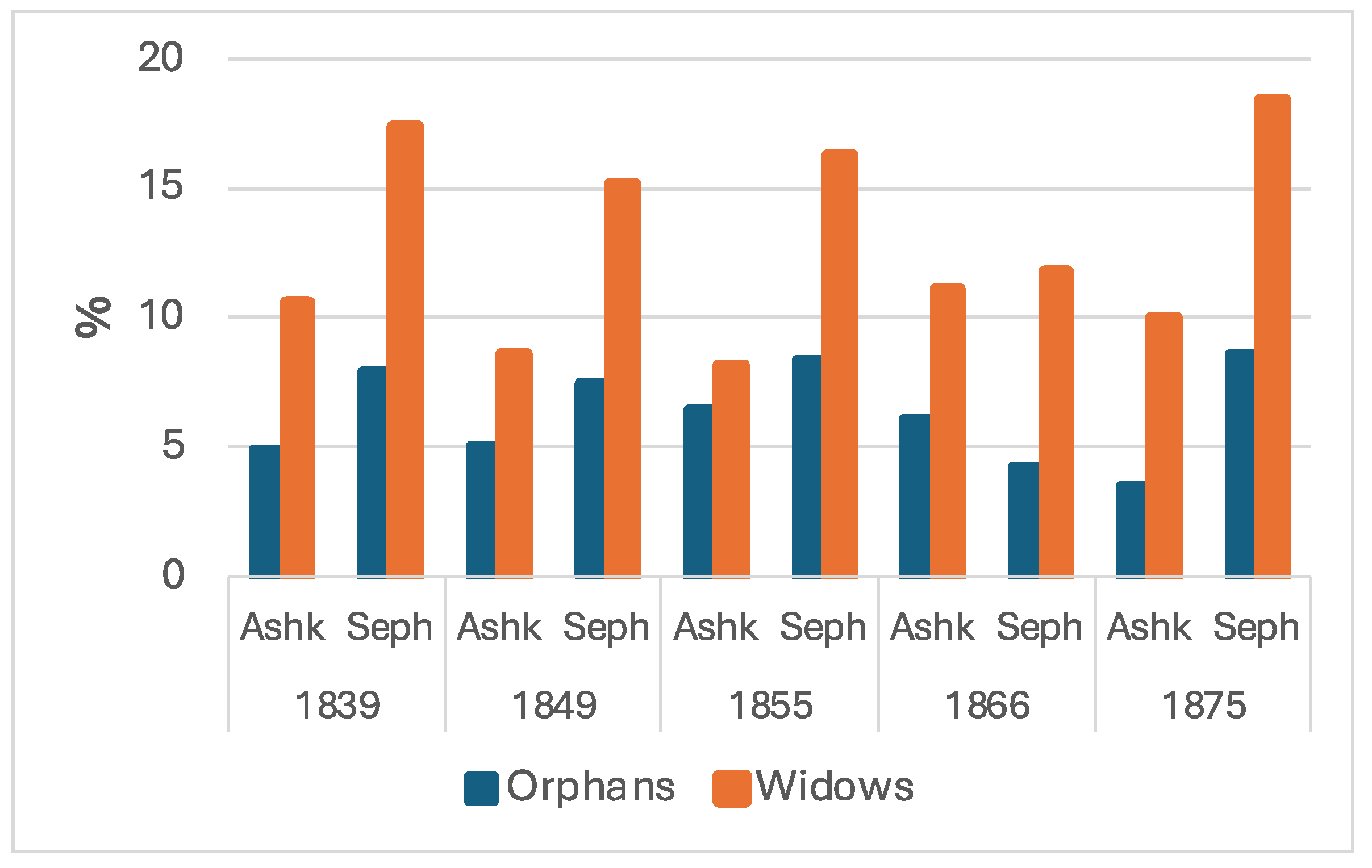

3.3.4. Marriage and Marital Status

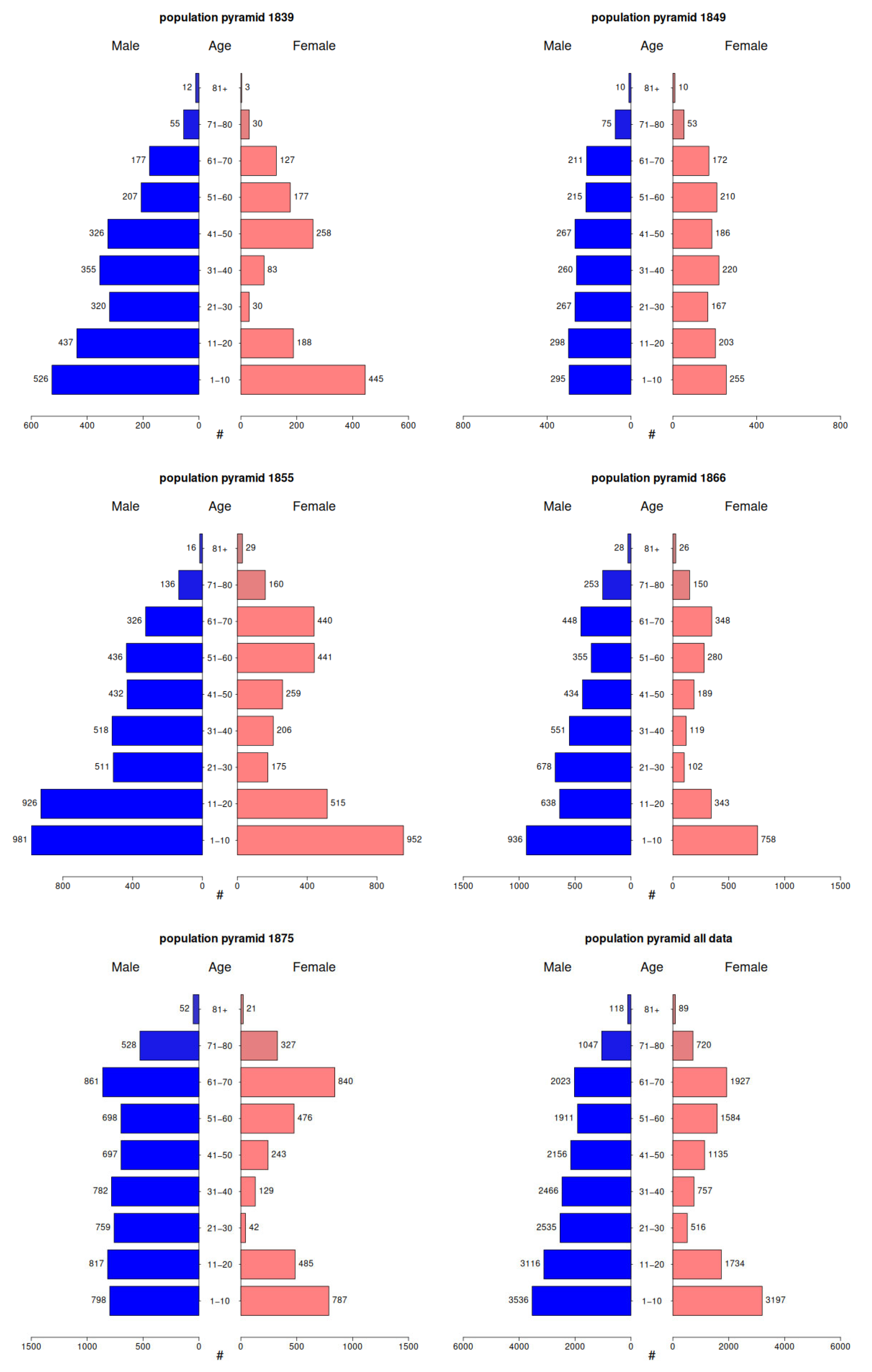

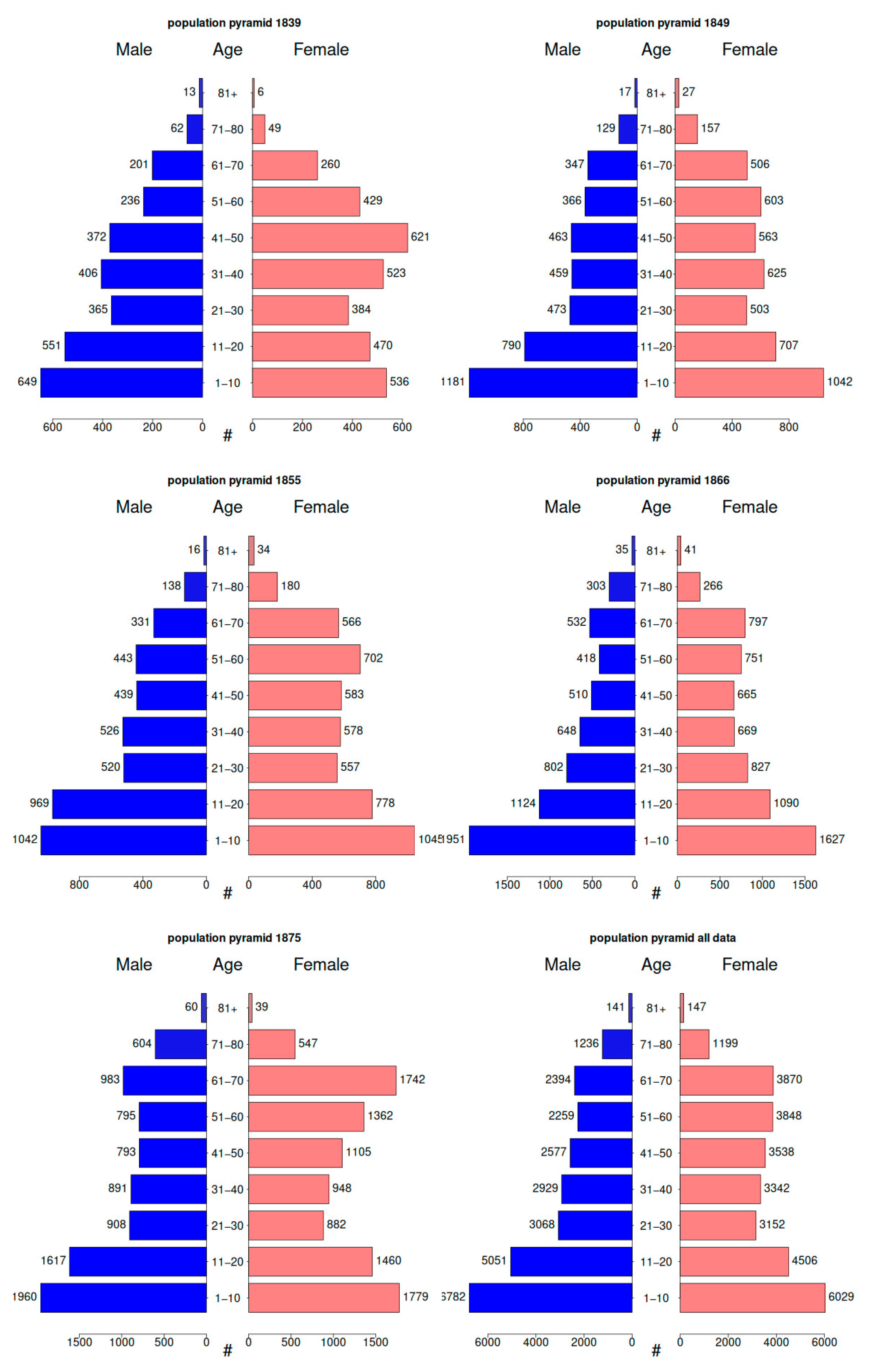

3.3.5. Age Composition

- For each typological category of family status such as child, orphan, single, and widowed, but with the exception of married adults, the cases with missing ages were assumed to distribute like those of the same category in the same census.

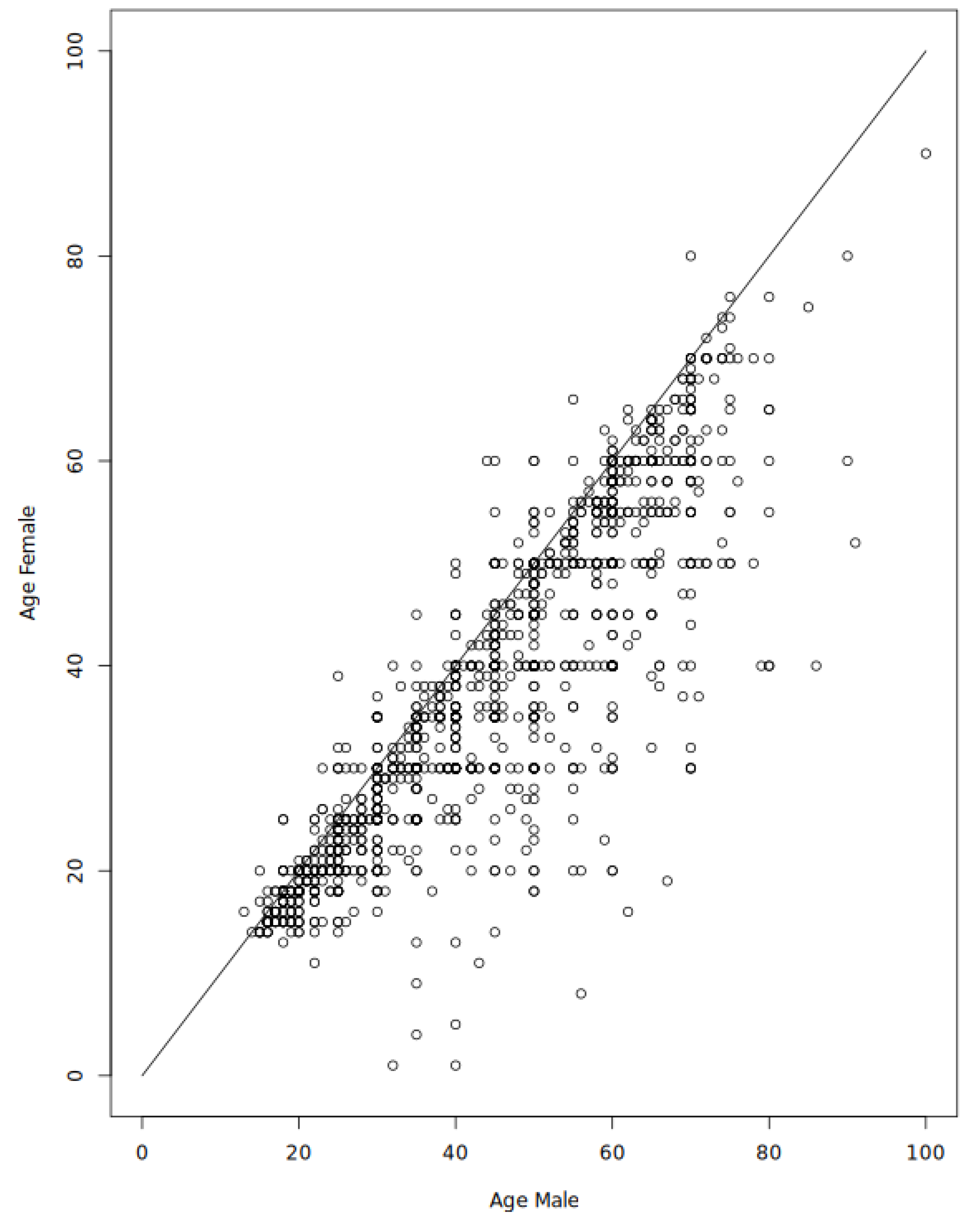

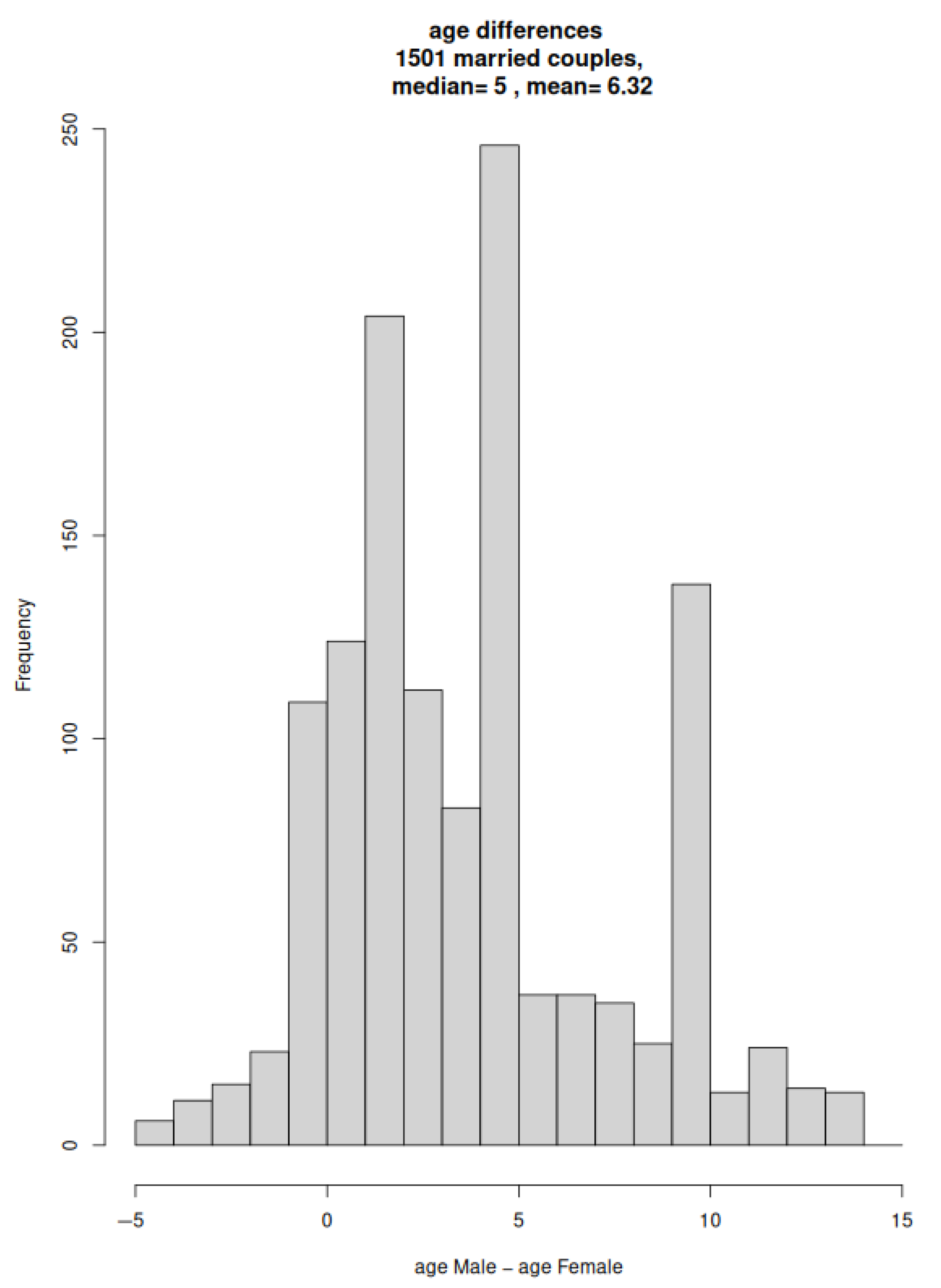

- For married individuals with missing age but the age of whose spouse was known, the woman was assumed to be younger by five years, in conformity with the average age-gap of married adults when the age of both was reported. The imputation was carried out for each census separately.

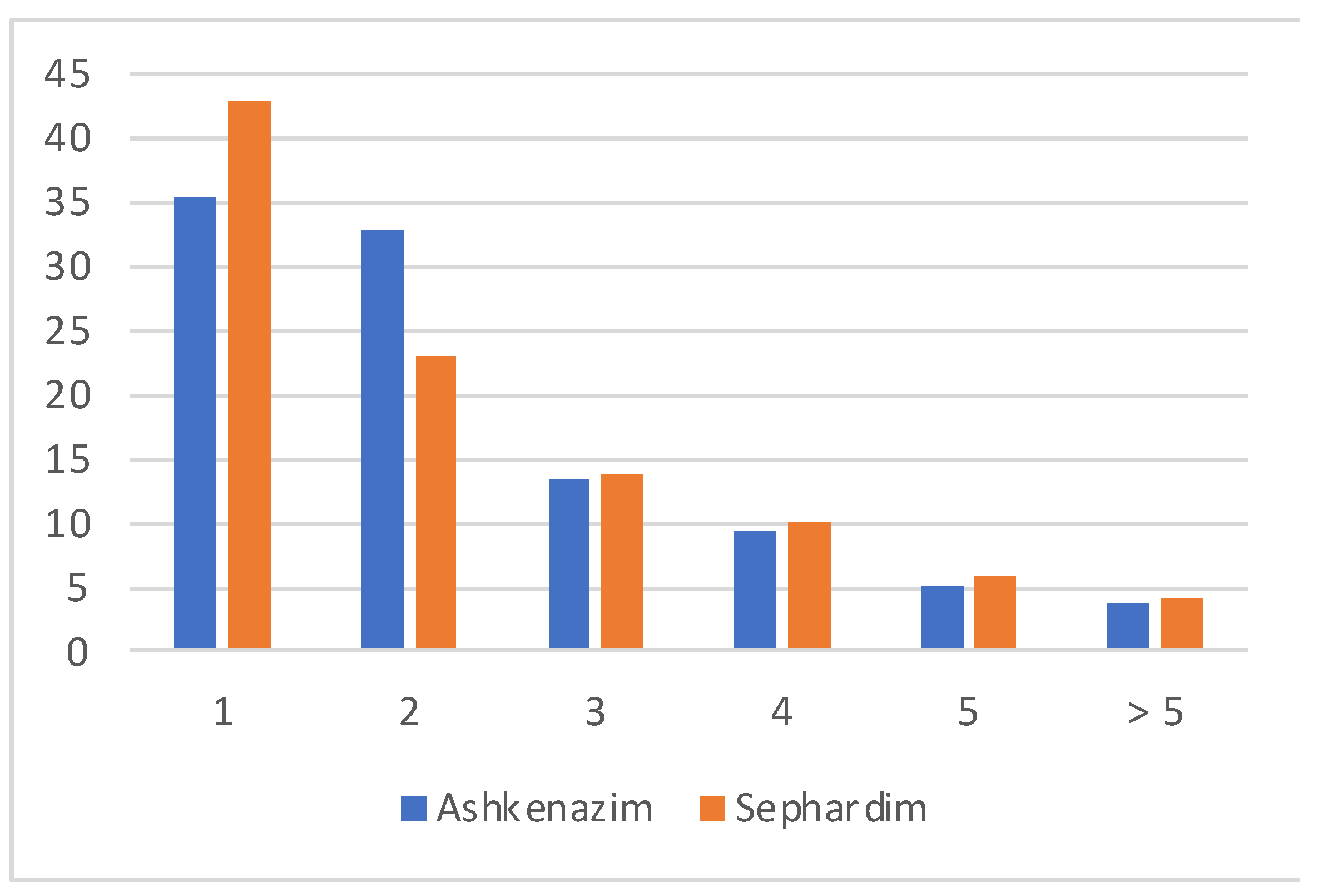

3.3.6. Family Composition

3.3.7. Immigration Waves

3.3.8. Occupation and Socio-Economic Status

Occupation

Socio-Economic Status

3.3.9. Surnames

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Methodological Details

Appendix A.1. Census Locations

- 1839: Acre, Haifa, Hebron, Jaffa, Jarmak (Djermek), Jerusalem, Safed, Saida (Lebanon), Shfaram, Shkhem, Tiberias;

- 1840: Alexandria (Egypt);

- 1849: Acre, Beirut (Lebanon), Haifa, Hebron, Jaffa, Jerusalem, Ramla, Safed (includes Safed and amp; Tiberias and Safed and amp; Upper Galilee), Shfaram, Shkhem, Pekiin, Tiberias;

- 1855: Acre, Haifa, Hebron (Hebron and amp; Jerusalem), Jaffa (includes Jaffa/Ramla), Jerusalem, Safed, Saida (Lebanon), Shfaram, Shkhem, Pekiin, Tiberias;

- 1866: Haifa, Hebron, Jaffa, Jerusalem, Safed, Saida (Lebanon), Shkhem, Pekiin, Tiberias;

- 1875: Haifa, Hebron, Jaffa, Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias.

Appendix A.2. Classification of Occupations

- Agriculture (dung carrier);

- Extraction of minerals;

- Manufacturing industries:

- ○

- Textile industries (blankets and pillow maker);

- ○

- Chemical industries;

- ○

- Wood manufacture (carpenter);

- ○

- Metal and mechanical industries (silversmith, jewel, watchmaker);

- ○

- Building industries (house painter);

- ○

- Printing and stationery industries (book binder and book seller);

- ○

- Food manufacture, fisherman (all food jobs and ritual slaughters);

- ○

- Clothing and millinery industries (hosiery, seamstress);

- ○

- Leather industries (shoemaker, cobbler);

- ○

- Other industries;

- ○

- Undefined industries;

- Transport and communication (donkey driver);

- Domestic service (servant, barber, bleacher);

- Financial service (added; charity collection, emissaries);

- Community service (added; charity distribution, good deeds doers, bath attendant);

- Commerce (all buy and sell jobs, including food stores);

- Clerical work (clerk, scribe, translator);

- Public officials, police, army;

- Craftsman and small jobs (grave digger, journeyman)

- Professions and liberal arts:

- ○

- Medicine (health professional, bloodletting, pharmacist);

- ○

- Engineering;

- ○

- Education;

- ○

- Arts;

- ○

- Other liberal professions (homeowner, hostel, real estate);

- ○

- Religious occupations (rabbis, Torah scholar having no other occupations, mezuzot and Torah scribes, persons involved in the preparation of kosher meat, worshippers);

- Students (any individuals who studied Torah not being a Torah scholar and having no other occupation);

- Persons of no occupation and dependents (including “batlanim” for minyan and unemployed);

- Unknown (including “agent” with no other precision).

Appendix A.3. Tables of Currency Conversion

- 1 Turkish Lira = 100 Grush.

- 1 French Franc = 10 Grush.

- 1 British Pound = 250 Grush.

- 1 Ducat = 3000 Grush.

- 1 Russian Rouble = 25 Grush.

- 1 Austrian Gulden = 2500 Grush.

- 1 French Napoleon = 2000 Grush.

- 1 Thaler = 400 Grush.

Appendix B. Supplementary Data

| Ashkenazim | Sephardim | |

|---|---|---|

| Surname | 95% | 3% |

| Place of birth | 9% | 24% |

| Age | 5% | 32% |

| Date of arrival (for HH not born in the Land of Israel) | 32% | 60% |

| Occupation | 44% | 50% |

| Economic status | 75% | 62% |

| Economic status as deduced from occupation and comments | 55% | 42% |

| Country | 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukraine | |||||

| Berdychiv | 2 | 35 | 82 | 63 | 91 |

| Khotin | 2 | 15 | 33 | 33 | 15 |

| Kolomyya | 4 | 13 | 18 | 29 | 50 |

| Total (including other places) | 88 | 375 | 697 | 825 | 1376 |

| Land of Israel | |||||

| Jerusalem | 478 | 87 | 368 | 296 | 726 |

| Safed | 52 | 110 | 117 | 253 | 212 |

| Tiberias | 30 | 65 | 60 | 162 | 158 |

| Hebron | 69 | 96 | 73 | 76 | 69 |

| Total (including other places) | 769 | 483 | 843 | 907 | 1349 |

| Belarus | |||||

| Shklow | 44 | 33 | 44 | 38 | 32 |

| Pinsk | 12 | 9 | 41 | 31 | 117 |

| Minsk | 11 | 10 | 25 | 44 | 56 |

| Total (including other places) | 193 | 160 | 341 | 414 | 699 |

| Morocco | |||||

| Meknes | 0 | 72 | 65 | 211 | 140 |

| Rabat | 6 | 17 | 41 | 105 | 141 |

| Marrakech | 8 | 48 | 56 | 51 | 8 |

| Total (including other places) | 31 | 184 | 224 | 710 | 558 |

| Turkey | |||||

| Istanbul | 177 | 51 | 148 | 28 | 246 |

| Izmir | 72 | 38 | 66 | 22 | 71 |

| Edirne | 47 | 18 | 33 | 6 | 61 |

| Total (including other places) | 355 | 132 | 306 | 86 | 493 |

| Poland | |||||

| Kalisz | 1 | 18 | 18 | 25 | 20 |

| Warszawa | 0 | 9 | 10 | 21 | 33 |

| Total (including other places) | 30 | 83 | 141 | 269 | 487 |

| Romania | |||||

| Iasi | 19 | 31 | 71 | 88 | 119 |

| Botosani | 9 | 13 | 18 | 32 | 71 |

| Total (including other places) | 51 | 89 | 169 | 235 | 399 |

| Greece | |||||

| Thessaloniki | 188 | 49 | 216 | 64 | 254 |

| Rhodos | 38 | 12 | 57 | 17 | 80 |

| Total (including other places) | 259 | 73 | 300 | 100 | 381 |

| Lithuania (mostly Vilnius) | 44 | 42 | 62 | 170 | 340 |

| North Africa (not else specified) | 67 | 53 | 46 | 58 | 169 |

| Georgia | 0 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 157 |

| Moldova (mostly Chisinau) | 5 | 55 | 85 | 133 | 147 |

| Syria | |||||

| Aleppo | 64 | 32 | 77 | 20 | 60 |

| Damascus | 15 | 35 | 63 | 45 | 41 |

| Total (including other places) | 79 | 67 | 142 | 65 | 101 |

| Algeria (mostly Oran) | 211 | 146 | 230 | 125 | 90 |

| Bulgaria (mostly Sofia) | 96 | 23 | 94 | 16 | 75 |

| North Macedonia (mostly Bitola) | 29 | 13 | 42 | 13 | 72 |

| Iraq | 19 | 18 | 28 | 30 | 70 |

| Bosnia | 27 | 18 | 37 | 11 | 35 |

| Russia | 7 | 9 | 3 | 20 | 34 |

| Latvia | 1 | 3 | 6 | 15 | 32 |

| Serbia (mostly Beograd) | 17 | 3 | 26 | 6 | 27 |

| Kurdistan | 4 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 26 |

| Iran | 6 | 20 | 34 | 14 | 16 |

| Germany | 4 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 11 |

| Tunisia (mostly Djerba) | 12 | 12 | 46 | 24 | 11 |

| Uzbekistan (all in Bukhara) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Hungary | 2 | 4 | 10 | 33 | 9 |

| Czechia | 0 | 6 | 13 | 16 | 7 |

| Cuba | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Lebanon | 0 | 11 | 15 | 17 | 5 |

| Libya (mostly Tripoli) | 0 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 5 |

| Netherlands | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| France | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Slovakia | 5 | 10 | 9 | 20 | 4 |

| India | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Yemen | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Italy (mostly Tuscany) | 16 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Portugal | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Saudia Arabia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Estonia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| USA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Austria | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Gibraltar | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Croatia | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| England | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown country | 628 | 1778 | 69 | 901 | 1014 |

| Census | 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 | All Censuses Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total individuals with known place of birth | 2531 | 2556 | 4349 | 4590 | 7423 | 21,364 |

| Individuals born in the Land of Israel | 805 | 732 | 1096 | 967 | 1417 | 5012 |

| Censuses | Number of Individuals | HH |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous stay | ||

| 1839, 1849 | 281 | 118 |

| 1839, 1849, 1855 | 357 | 123 |

| 1839, 1849, 1855, 1866 | 125 | 41 |

| 1839, 1849, 1855, 1866, 1875 | 241 | 59 |

| 1849, 1855 | 725 | 301 |

| 1849, 1855, 1866 | 295 | 95 |

| 1849, 1855, 1866, 1875 | 321 | 94 |

| 1855, 1866 | 211 | 81 |

| 1855, 1866, 1875 | 157 | 49 |

| 1866, 1875 | 891 | 302 |

| Total continuous stay | 3604 | 1263 |

| Discontinuous stay | ||

| 1839, 1855 | 120 | 42 |

| 1839, 1866 | 16 | 6 |

| 1839, 1875 | 20 | 6 |

| 1839, 1849, 1866, | 22 | 9 |

| 1839, 1849, 1855, 1875 | 40 | 12 |

| 1839, 1849, 1866, 1875 | 12 | 3 |

| 1839, 1855, 1866 | 25 | 8 |

| 1839, 1855, 1866, 1875 | 22 | 7 |

| 1839, 1855, 1875 | 16 | 7 |

| 1839, 1866, 1875 | 4 | 2 |

| 1849, 1866 | 78 | 29 |

| 1849, 1875 | 30 | 12 |

| 1849, 1855, 1875 | 61 | 23 |

| 1849, 1866, 1875 | 37 | 11 |

| 1855, 1875 | 150 | 53 |

| Total discontinuous stay | 653 | 230 |

| Duration of Stay | Census Dates | Individuals | HH |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 y | 1839, 1849 | 281 | 118 |

| 15 y | 1839, 1849, 1855 | 357 | 123 |

| 25 y | 1839, 1849, 1855, 1866 | 125 | 41 |

| 35 y | 1839, 1849, 1855, 1866, 1875 | 241 | 59 |

| 5 y | 1849, 1855 | 725 | 301 |

| 15 y | 1849, 1855, 1866 | 295 | 95 |

| 25 y | 1849, 1855, 1866, 1875 | 321 | 94 |

| 10 y | 1855, 1866 | 211 | 81 |

| 20 y | 1855, 1866, 1875 | 157 | 49 |

| 10 y | 1866, 1875 | 891 | 302 |

| 15 y | 1839, 1855 | 120 | 42 |

| 25 y | 1839, 1866 | 16 | 6 |

| 35 y | 1839, 1875 | 20 | 6 |

| 25 y | 1839, 1849, 1866, | 22 | 9 |

| 35 y | 1839, 1849, 1855, 1875 | 40 | 12 |

| 35 y | 1839, 1849, 1866, 1875 | 12 | 3 |

| 25 y | 1839, 1855, 1866 | 25 | 8 |

| 35 y | 1839, 1855, 1866, 1875 | 22 | 7 |

| 35 y | 1839, 1855, 1875 | 16 | 7 |

| 35 y | 1839, 1866, 1875 | 4 | 2 |

| 15 y | 1849, 1866 | 78 | 29 |

| 25 y | 1849, 1875 | 30 | 12 |

| 25 y | 1849, 1855, 1875 | 61 | 23 |

| 25 y | 1849, 1866, 1875 | 37 | 11 |

| 20 y | 1855, 1875 | 150 | 53 |

| 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | |

| Child | 418 | 1273 | 962 | 2039 | 1204 | 1672 | 1694 | 2572 | 2797 | 2749 |

| Adult | 1090 | 2548 | 1259 | 3400 | 1887 | 2567 | 2743 | 3437 | 4559 | 4340 |

| Old | 254 | 534 | 682 | 274 | 879 | 1112 | 1388 | 499 | 2301 | 1506 |

| Census | 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 | Old | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Total * | 1422 | 2216 | 1878 | 2752 | 1912 | 2523 | 2440 | 3722 | 3267 | 5628 | 5101 | 4324 |

| Unmarried | 203 | 20 | 255 | 28 | 420 | 109 | 341 | 98 | 520 | 243 | 627 | 5 |

| 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | ||

| Acre | 248 | 275 | 187 | 710 | |||||||

| Haifa | 16 | 123 | 152 | 14 | 531 | 836 | |||||

| Hebron | 172 | 246 | 115 | 231 | 270 | 249 | 228 | 280 | 489 | 450 | 2730 |

| Jaffa | 86 | 3 | 237 | 351 | 1 | 518 | 16 | 643 | 1855 | ||

| Jerusalem | 491 | 2424 | 1171 | 3351 | 1652 | 2882 | 2282 | 3486 | 5202 | 5987 | 28,928 |

| Pekiin | 76 | 63 | 60 | 199 | |||||||

| Ramla | 8 | 8 | |||||||||

| Safed | 616 | 770 | 1018 | 840 | 1341 | 717 | 2337 | 1212 | 3753 | 12,604 | |

| Shfaram | 106 | 118 | 114 | 338 | |||||||

| Shkhem | 75 | 70 | 59 | 4 | 60 | 268 | |||||

| Tiberias | 474 | 323 | 611 | 554 | 775 | 661 | 1050 | 1033 | 391 | 1161 | 7033 |

| Total | 1769 | 4401 | 2918 | 5760 | 4038 | 5435 | 5916 | 6649 | 9851 | 8772 | 55,509 |

| 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | |

| Orphans | 87 | 348 | 147 | 429 | 261 | 456 | 362 | 284 | 343 | 756 |

| Others * | 1494 | 3288 | 2521 | 4415 | 3447 | 4098 | 4899 | 5580 | 8521 | 6405 |

| Widows | 187 | 765 | 250 | 866 | 330 | 882 | 655 | 783 | 987 | 1611 |

| Total | 1768 | 4401 | 2918 | 5710 | 4038 | 5436 | 5916 | 6647 | 9851 | 8772 |

| 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | ||

| Agriculture | 2 | 17 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 55 | ||

| Art | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 24 | ||

| Building industry | 2 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 26 | 9 | 89 |

| Clerical work | 19 | 16 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 19 | 13 | 13 | 38 | 12 | 171 |

| Clothing and millinery industries | 22 | 58 | 34 | 78 | 56 | 116 | 46 | 54 | 140 | 29 | 633 |

| Commerce | 46 | 188 | 28 | 183 | 57 | 266 | 149 | 327 | 390 | 309 | 1943 |

| Community service | 4 | 2 | 2 | 24 | 14 | 19 | 6 | 17 | 5 | 93 | |

| Craftsman and small jobs | 34 | 8 | 60 | 20 | 129 | 12 | 58 | 86 | 55 | 462 | |

| Domestic service | 3 | 62 | 1 | 93 | 1 | 210 | 3 | 120 | 48 | 225 | 766 |

| Education | 25 | 21 | 39 | 18 | 58 | 46 | 91 | 34 | 177 | 33 | 542 |

| Financial service | 5 | 24 | 12 | 15 | 2 | 16 | 4 | 26 | 16 | 32 | 152 |

| Food manufacture | 10 | 59 | 21 | 66 | 38 | 143 | 60 | 119 | 82 | 58 | 656 |

| Health and medicine | 4 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 24 | 21 | 11 | 36 | 7 | 137 |

| Leather industries | 4 | 33 | 9 | 32 | 24 | 68 | 28 | 111 | 68 | 45 | 422 |

| Metal and mechanical industries | 18 | 43 | 21 | 44 | 37 | 62 | 44 | 79 | 88 | 48 | 484 |

| Other liberal profession | 4 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 38 | ||

| Persons of no occupation and dependents | 3 | 64 | 1 | 245 | 18 | 141 | 31 | 195 | 316 | 68 | 1082 |

| Printing and stationery industries | 7 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 18 | 3 | 22 | 48 | 6 | 116 | |

| Public official, police, army | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 17 | |

| Religious occupation | 77 | 162 | 221 | 281 | 171 | 176 | 341 | 101 | 488 | 154 | 2172 |

| Students | 155 | 192 | 45 | 91 | 276 | 129 | 346 | 364 | 590 | 192 | 2380 |

| Textile industries | 1 | 5 | 14 | 1 | 46 | 4 | 7 | 20 | 4 | 102 | |

| Transport and communication | 3 | 23 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 18 | 35 | 11 | 34 | 138 | |

| Undefined industry | 40 | 78 | 19 | 27 | 16 | 20 | 200 | ||||

| Wood manufacture | 6 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 27 | 16 | 64 | 9 | 156 |

| Unknown | 426 | 1131 | 780 | 1295 | 881 | 688 | 1329 | 926 | 1431 | 2658 | 11,512 |

| Total | 882 | 2193 | 1263 | 2615 | 1729 | 2357 | 2619 | 2648 | 4213 | 4023 | 24,542 |

| 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | Ashk | Seph | |

| High | 30 | 7 | 14 | 34 | 17 | 52 | 45 | 36 | 107 | 242 |

| Medium | 89 | 214 | 229 | 213 | 233 | 196 | 342 | 246 | 524 | 338 |

| Low | 21 | 429 | 66 | 462 | 230 | 360 | 313 | 579 | 1230 | 21 |

| Very Low | 460 | 1079 | 135 | 545 | 80 | 1542 | 174 | 701 | 1041 | 623 |

| ND | 259 | 462 | 766 | 1361 | 1167 | 207 | 1741 | 1085 | 1311 | 1925 |

| Total | 859 | 2191 | 1210 | 2615 | 1727 | 2357 | 2615 | 2647 | 4213 | 4017 |

References

- Aaronsohn, Ron. 1995. The Beginnings of Modern Jewish Agriculture in Palestine: “Indigenous” versus “Imported”. Agricultural History 69: 438–53. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Cyrus, and Judah Eisenstein. 1901–1906. Ḥaluḳḳah. In The Jewish Encyclopedia. Edited by Isidore Singer. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Available online: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7115-halukkah (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Alroey, Gur. 2014. An unpromising land: Jewish migration to Palestine in the early twentieth century. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bachi, Roberto. 1977. The Population of Israel. Jewish Population Studies 11. Paris: CICRED. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. [Google Scholar]

- Beider, Alexander. 2023. Surnames of Jewish People in the Land of Israel from the Sixteenth Century to the Beginning of the Twentieth Century. Genealogy 7: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Arieh, Yehoshua. 1984. Jerusalem in the 19th Century: The Old City. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ya’akov, Michal. 1994. The immigration of North African Jews to Nineteenth-century Eretz Israel: Origin and Destination. Proceedings of the Eleventh World Congress of Jewish Studies 3: 208–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ya’akov, Michal. 2001. The Montefiore Census: The First Modern Census of Jews in Erez Israel. In Papers in Jewish Demography, 1997 ed. Edited by Sergio DellaPergola and Judith Even. Jewish Population Studies 29. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Institute of Contemporary Jewry, pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ya’akov, Michal. 2004. Aliyah in the Lives of North African Jewish Widows: Realization of a Dream or Solution to a Problem? Nashim, a Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues 8: 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ya’akov, Michal. 2006. Widows in the North African Jewish Communities of Late Ottoman Palestine. Encyclopedia of Jewish Women’s Archive. Available online: https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/widows-in-north-african-jewish-communities-of-late-ottoman-palestine (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Ben Ya’akov, Michal. 2012. Space and Place: North African Jewish Widows in Late-Ottoman Palestine. Journal of Women of the Middle East and the Islamic World 10: 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 1983. La trasformazione demografica della diaspora ebraica. Torino: Loescher. [Google Scholar]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 1992. Review of: Population of Palestine: Population History and Statistics of the Late Ottoman Period and the Mandate, by J. McCarthy. Studies in Zionism 13: 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2012. Some Reflections on Migration in Israel: Comparative Aspects. Hagira–Israel Journal of Migration 1: 5–31. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2020. Diaspora vs. Homeland: Development, Unemployment and Ethnic Migration to Israel, 1991–2019. Jewish Population Studies 31. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, The Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry. [Google Scholar]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2021. A Minimal Demographic History of Israel. In The Oxford Handbook of Israeli Politics and Society. Edited by Reuven Y. Hazan, Alan Dowty, Menachem Hofnung and Gideon Rahat. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2024a. Notes toward a Demographic History of the Jews. Genealogy 8: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2024b. Demography of the Jewish family: Continuities and discontinuities. In The Jewish Family in Global Perspective. Edited by Harriet Hartman. Cham: Springer, pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dulska, Anna Katarzyna. 2015. Diaspora żydowska na Bliskim Wschodzie oczami sefardyjskiego podróżnika Beniamina z Tudeli. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. [Google Scholar]

- Dulska, Anna Katarzyna. 2017. Abrahamic coexistence in the twelfth-century Middle East? Jews among Christians and Muslims in a travel account by a Navarrese Jew, Benjamin of Tudela. Journal of Beliefs & Values 38: 257–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, James. 1868. Byeways in Palestine. London: James Nisbet & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, Jonathan. 1997. The Damascus Affair: “Ritual Murder”, Politics and the Jews in 1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gelber, Yoav. 2007. The History of Jewish Historiography: From Apology to Denial. In Making Israel. Edited by Benny Morris. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, Joseph B., and Ruth Kark. 1991. Sephardi entrepreneurs in Eretz Israel. The Amzalak Family 1816–1918. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guérin, Honoré Victor. 1868. Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine. Paris: L’Imprimerie impériale, vol. 1: Judée, pt. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kark, Ruth. 1994. American Consuls in the Holy Land. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Daniel. 2016. The Jewish community in nineteenth century Palestine: Evidence from the Montefiore censuses. Middle Eastern Studies 52: 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestschinsky, Jacob. 1929. Die Umsiedlund und Umschichtung des jüdischen Volkes im Laufe des letzten Jahrhuderts. Weltwirtschaftsliches Archiv 20: 123–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lestschinsky, Jacob. 1960. Jewish migrations, 1840–1956. In The Jews: Their History, Culture and Religion, 3rd ed. Edited by Louis Finkelstein. New York: Harper, vol. 2, pp. 1536–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Bernard. 1952. Notes and Documents from the Turkish Archives: A Contribution to the History of the Jews in the Ottoman Empire. Jerusalem: The Israel Oriental Society, Oriental Notes and Studies, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Linfield, Harry S. 1939. The Jews of the United States number and distribution: Preliminary figures for 1937. The American Jewish Year Book 41: 181–86. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1854. Declaration of War. On the History of the Eastern Question. New York Daily Tribune, April 15. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Justin. 1990. The Population of Palestine. Population History and Statistics of the Late Ottoman Period and the Mandate. New York and Oxford: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McEvedy, Colin, and Richard Jones. 1978. Atlas of World Population History. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Montefiore, Moses, and Judith Cohen Montefiore. 1890. Diaries of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore: Comprising Their Life and Work as Recorded in their Diaries from 1812 to 1883. Edited by Louis Loewe. Chicago: Belford-Clark Co. [Google Scholar]

- Palestine Office of the World Zionist Organization. 1918–1919. Sephirat Yehudey Eretz Israel [Enumeration of the Jews in Palestine]. Jaffa: Palestine Office of the World Zionist Organization. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, U. O. 1971. Infant and Early Childhood Mortality Among the Jews of the Diaspora. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, Institute of Contemporary Jewry. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, U. O. 1985. The Place of the Montefiore Censuses in the History of the Jewish Population in Palestine. Tel Aviv: Montefiore Congress. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, U. O. 1987. Modern Jerusalem’s Demographic Evolution. Jerusalem: The Institute of Contemporary Jewry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, U. O. 1990. Population Characteristics of Jerusalem and Hebron Regions according to Ottoman Census of 1905. In Ottoman Palestine 1800–1914: Studies in Economic and Social History. Edited by Gad Gilbar. Leiden: Brill, pp. 15–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, U. O. 1992. Review of: Population of Palestine: Population History and Statistics of the Late Ottoman Period and the Mandate, by J. McCarthy. Middle Eastern Studies 28: 803–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz, U. O., and Sergio DellaPergola. 2006. Migration. In Encyclopedia Judaica, 2nd ed. Edited by Fred Skolnik. Farmington Hills: Thomson Gale, vol. 14, pp. 207–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, Norman A. 1979a. Jews of the Maghreb in the Late Modern Era. In International Journal of Middle East Studies 11: 481–512. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, Norman A. 1979b. The Jews of Arab Lands. A History and Source Book. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 0-8276-0116-6. [Google Scholar]

- The Montefiore Endowment. n.d. Available online: https://www.montefioreendowment.org.uk/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Weinryb, Bernard. 1972. The Jewish Population in Eastern Europe Between the Wars: Demographic and Social Trends. Jewish Social Studies 34: 139–60. [Google Scholar]

| City | 1839 | 1849 | 1855 | 1866 | 1875 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 248 | 281 | 187 | ||

| Haifa | 139 | 152 | 14 | 531 | |

| Hebron | 418 | 346 | 519 | 508 | 939 |

| Jaffa | 86 | 264 | 254 | 538 | 660 |

| Jerusalem | 2915 | 4522 | 4534 | 5768 | 11,189 |

| Pekiin | 76 | 63 | 60 | ||

| Ramla | 8 | 97 | |||

| Safed | 1391 | 1858 | 2059 * | 3549 | 3753 |

| Shfaram | 106 | 118 | 114 | ||

| Shkhem | 75 | 84 | 59 | 64 | |

| Tiberias | 800 | 1165 | 1436 | 2083 | 1552 |

| Total | 6178 | 8722 | 9474 | 12,584 | 18,624 |

| City | Jewish Households in 1866 Montefiore Census | Jewish Households in 1868–1869 Ottoman Statistics | Total Households in 1868–1869 Ottoman Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | - | 6 | 763 |

| Gaza | - | - | 2755 |

| Haifa | 7 | 8 | 452 |

| Hebron | 197 | 200 | 3000 |

| Jaffa | 181 | - | 1141 |

| Jerusalem | 2520 | 630 | 2347 |

| Nazareth | - | - | 1368 |

| Pekiin | 24 | - | |

| Ramla | 925 | ||

| Safed | 1463 | 1197 | 2495 |

| Shkhem (Nablus) | 21 | - | 1466 |

| Tiberias | 863 | 400 | 625 |

| Total | 5296 | 2435 | 17,337 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levy-Toledano, R.; Penninx, W.; DellaPergola, S. Jewish Presence in the Land of Israel in the 19th Century: Insights from the Montefiore Censuses. Genealogy 2025, 9, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9030072

Levy-Toledano R, Penninx W, DellaPergola S. Jewish Presence in the Land of Israel in the 19th Century: Insights from the Montefiore Censuses. Genealogy. 2025; 9(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevy-Toledano, Raquel, Wim Penninx, and Sergio DellaPergola. 2025. "Jewish Presence in the Land of Israel in the 19th Century: Insights from the Montefiore Censuses" Genealogy 9, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9030072

APA StyleLevy-Toledano, R., Penninx, W., & DellaPergola, S. (2025). Jewish Presence in the Land of Israel in the 19th Century: Insights from the Montefiore Censuses. Genealogy, 9(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9030072