1. Introduction

In 1858, Griqua Captain (

Kaptyn) Cornelis Kok II (1778–1858) died at roughly the age of 80. His grave remained undisturbed until 1961, when a coalition of scientists, a white farmer, and a claimant to Griqua traditional leadership worked together to identify and exhume his remains.

1 After decades in storage and study at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), and shifts in the South African political landscape, the remains were ultimately returned to the Northern Cape town of Campbell, a key site in Griqua history and heritage, where they were reburied in 2007. Tracing the life history of Kok’s human remains reveals shifting regimes of memory, identity formation, and political contestation in modern South Africa.

Kok’s remains took on a trajectory that was far from typical, beginning with the 1961 exhumation. A multiracial coalition worked together during the ascendancy of grand apartheid with the intent not of racial scientific research that was fashionable at the time, but rather towards community-based historical restoration and preservation. The exhumation itself, first projected for relocation within a historical mission precinct, included the participation of additional researchers. The expertise and authority of paleoanthropologist Phillip Tobias brought new meaning and direction to the excavation, and the remains became objects of scientific research geared towards both provenance and the affirmation of identity for the Griqua participants. In short order, the research team ushered the remains purported to be Kok’s, along with 34 others presumed to be Griqua, to Wits. Contrary to the initial objectives and plans, the university retained the remains.

Reflecting the post-apartheid political dispensation and norms of the 1990s global indigenous rights movement, Griqua and Khoisan activists agitated for the return of the remains, leading to Tobias ceremonially handing them over in 1996 and their re-burial in 2007. Both in the circumstances regarding their excavation and the contestations over their repatriation, the afterlife of Cornelis Kok II’s bones provides a case study in shifting political meanings and identities projected on and enacted through human remains. This begins with an unusual and unequal multiracial coalition at the height of apartheid rule, moving towards revitalized post-apartheid claims to heritage restoration as social justice, and an embrace of an ascendant Khoisan identity,

2 ultimately towards contemporary claims for government recognition of traditional leadership. In exploring the biography of these bones, we draw upon documentary archival materials, photography, oral history, and for one of us, a regional heritage practitioner, auto-ethnography. Cornelis Kok II’s remains have injected life into political contestation well beyond the man’s natural life.

The circumstances surrounding the excavation of Kok’s remains are slippery yet instructive. While the process inevitably was shaped by the entrenched racial inequality of apartheid, it was only made possible by the participation of Griqua Captain Adam Kok IV (1889–1978). Kok IV worked alongside a white farmer and informal local power broker, Basil Humphreys, who then liaised with researchers from the McGregor Museum in Kimberley and Wits. Kok IV had his own motivations to exhume Kok II’s remains, to relocate them, and thus preserve them at a time when the original grave was under threat. Given the politics of the time, this could have also contributed towards cementing his own position as leader in the community. This dynamic was ambiguous. Kok IV required the support of a white farmer and white researchers for recognition and support in the quest for identity affirmation. This could plausibly lend itself to colonial-style distortion of traditional leadership claims. Both men, one a claimant to Griqua leadership, the other a prominent white farmer with an interest in local history, shared a commitment to the Anglican church as a core part of their identity and role in public life. Unlike many other exhumations of human remains under colonial and apartheid conditions—often constituting clear acts of theft and degradation—in this instance, the excavation and scientific tools brought to bear on Kok II’s remains offered a pathway to corroboration of Griqua identity and communal status for Kok IV.

With Adam Kok IV’s passing and the advent of democracy in the 1990s, the meanings and struggles imputed to Cornelis Kok II’s remains changed again. Kok II’s remains took on regional, national, and global valences while new actors took pressing interest in them. Griqua, Khoisan and indigenous peoples’ rights activists increasingly drew on the global zeitgeist encapsulated by the United Nations Decade of the World’s Indigenous People (1995–2004). (For literature on regional and wider African identification with and participation in the global indigenous peoples’ rights movement, see (

Hodgson 2009); (

Maruyama 2018); (

Sylvain 2014)). A wide range of actors increasingly drew upon this framework and applied it to national calls to return Saartjie Baartman and King Hintsa’s remains (e.g.,

Mkhize 2009;

Crais and Scully 2008;

Tobias 2002). In doing so, they both located Kok II’s bones within a narrative of national reckoning and postcolonial reparations while also deepening Griqua attachments to Khoikhoi, Khoisan, and indigenous identities. For their part, Tobias and other researchers accommodated these pressures and post-apartheid imperatives in releasing the remains for restitution and reburial.

Today, Adam Kok V, grandson of Adam Kok IV, an acting claimant to Griqua leadership, draws upon the remains to express twinned concerns and objectives. First, he laments the current state of Cornelis Kok II’s reburial site as a means of signalling injustice against his family and neglect of Griqua and Khoisan communities. Second, he continues to draw upon the excavation of Cornelis Kok II’s remains—and the very relationships and characters who enabled it—in his genealogical claims to Griqua leadership and thus government recognition. Indeed, while Kok II’s remains have shifted locations from the original burial site to Wits and back to Campbell once again, the meanings and contestations over them have equally transformed.

In examining the biography of Cornelis Kok II’s remains, we demonstrate how they have shaped and continue reshaping our social and cultural world. As a locus of what

Andrew Meirion Jones (

2012, pp. 196–97) characterizes as “extended sociality”, they serve as a key feature, even a “co-producer”, in the making and refining of cultural scripts into the 21st century.

Hans Ruin (

2018, p. 88) similarly treats “sociality as an ontological domain that comprises both the living and the dead”, such that the social world emerges from an interplay between the living and the dead. The latter in this instance, the bones of Cornelis Kok II, palpably continue to feature in and mould public life, first from the grave, then in their excavation, in their ceremonial repatriation, and in their ultimate reburial.

2. A Brief History of the Griqua and Cornelis Kok II

Griqua history evinces dynamics of political absorption and fracture. Griqua societies emerged amid the vicissitudes of 18th and 19th century settler colonialism and the expansion of the South African frontier. This was a turbulent world, akin to what

James Scott (

2009, pp. 7–8), writing in another context, identified as a “shatter zone”, in which various states mushroomed while others crumbled, entangling diverse groups of people along the edges of expanding states. Often a step ahead of the white colonialists, the Griqua emerged as a composite society absorbing communities and individuals through conquest, accommodation, and refuge. This included a spectrum of San, Khoi, Korana, whites, Batswana, and others; in form, function, and structure, Griqua settlements constituted the prototypical frontier society (

Kopytoff 1987). The emergence and composition of Griqua societies reflect what

Christopher Saunders (

1981, p. 159) noted as, “The fluidity of politics in the frontier zone…”, in which alliances and identities were malleable to shifting local political dictates. Griqua social organization and economic processes shaped, and were shaped by, contact with raiding and pastoralist Khoi clans, Trekboer insurgents, and trade with Tswana polities (

Penn 2005;

M. C. Legassick 2010). In the late 18th century, Christian conversion of Griqua settlements began through interaction with the London Missionary Society (LMS) (see

Ross 1976).

The Griqua emerged as a frontier, composite society shaped by the dynamics of what Martin Legassick (

M. C. Legassick 2010) identified as the 18th and 19th century “frontier zone”; accordingly, Griqua society has historically been quite factional. Cornelis Kok II’s leadership emerged in this context. As Captain, he broke away from the dominant Griqua leadership based in Griquatown, establishing his own lineage and grouping some 50 km away in Campbell.

3 In 1858, following his death, Kok II was buried just north of Campbell, on what later became a privately held farm. Within two decades of his passing, white settlers—both British and Trekboer—crushed Griqua power and self-determination, ultimately seizing their land (

Kurtz 1988). This turbulence was further accelerated by the diamond rush in the region from the late 1860s onwards. This led to the dismantling and disempowerment of Griqua political structures and independence, leading to the subsumption of Griqua descendants into state imposed, ill-defined Coloured identities.

In the late 19th and 20th centuries, community identities, histories, and heritage were again reconfigured by competing interests, political upheavals, and marginalization, as well as both inwards and outwards migration. As Michael Besten (

M. P. Besten 2006, p. 11) notes, the interplay between colonial and African societies, “generated composite Griqua subjectivities, opening them to a multiplicity of socio-political directions…” Just as the making and unravelling of Griqua political and social structures mirror each other in complexity, the logics of fusion and diffusion persist throughout Griqua history. Genealogical and historical confusion results from loss of land, and of status, autonomy, and memory. As Steven L. Robins (

S. L. Robins 2008, pp. 36–37) highlights, minoritized historical identities are often pieced together from fragments, precisely due to the shattering inherent in the expansion of the frontier, attended by settler colonial violence, the onset of missionary activity, and eventual colonial and apartheid rule; in a sense, the very fragmentation in political identity and historical imagination itself reflects the “shattering” caused by conquest. In this instance, following

Ruin (

2018), we trace how bones, which

Fontein (

2022, p. 40) recognizes as being imbricated with an “emotive materiality and affective presence”, serve as a fulcrum for forging kinship, anchoring historical memory, and making political claims in the aftermath of colonial and apartheid rule.

3. A Tale Told Through Bones: Considerations of Big Men, Life Histories, and Technological Reappropriation

In his study of Griqua historiography,

Edward Cavanagh (

2011, pp. 116–17) concludes, “Griqua history remains fertile ground for researchers…[yet] it is one in which tragic and gloomy narratives predominate; it is one in which the story is still told through the eyes of the ‘big men’…”. Ultimately, Cavanagh laments, Griqua historiographically continue to be “…pinned up as oddities who always compare poorly to the more successful of their neighbours.” Rather than tell a story through the eyes of “the big men” as such, we examine the assertions and counter-assertions to ownership of the contemporary legacy of one of these figures, including latter-day claims to historical “big man” or leadership status grounded in genealogical ties to the remains exhumed at Campbell in 1961. We show how different actors with various motivations and in interaction with wider phenomena draw on the remains of Cornelis Kok II to challenge the notion of Griquaness existing merely “as an anomaly…something with a strong history, but a weak presence” (

Cavanagh 2011, p. 116). In short, we bring a history of memory practices and controversies to demonstrate how Griquaness is embedded in and connected to wider local, regional, national, and global phenomena.

Human remains have long been a flashpoint in South African political culture and historiography.

Rebekah Lee (

2011, p. 226) highlights how “death figures prominently in the lives of urban Africans.” Mortuary politics have served as terrain for the negotiation of colonial and segregationist dynamics (

G. M. Dennie 2003,

2009). Yet, it is the acquisition, analysis, storage, and repatriation of human remains that often takes centre stage in post-apartheid discourse. In 2000,

Legassick and Rassool (

2000, pp. 1–2) confronted what they termed “a conspiracy of silence”, rooting often unethically acquired skeletons as central to the development of the country’s museums, underpinned by “a competitive and insatiable trade in human remains…of the newly dead, and in some cases, of the still-living”.

Samuel J. Redman (

2016, p. 36) observed in another context that, “As behind-the-scenes museum collecting expanded…[the] exhibition of human remains also became more commonplace.” Often ill-gotten remains were central to imperial productions of Africa for western audiences, particularly through museums (

Coombes 1994). Offering a different take,

Premesh Lalu (

2009) drew on King Hintsa’s colonially extracted human remains to refigure the parameters of historiography.

4 Indeed, as

Nomalanga Mkhize (

2009) demonstrates, quests for repatriation can also be attempts to reclaim the means of historical production and narration, particularly as the colonial collecting of human remains has a history in its own right (

Webb 2015).

At times collected from contexts of colonial violence, human remains carry their own multi-variegated histories, and lend themselves to different historical projects. As

Christopher Heaney (

2023) demonstrates, they often admit radically different meanings and values for different actors across time and place.

Zine Magubane (

2001, p. 827) charges that various “interested social actors” driven by their specific “social and political commitments” offer a range of interpretations of the body shaped by shifting social relations. Borrowing from

Ricardo Roque (

2011, p. 18), Cornelis Kok II’s remains are not “a thing in itself, but a composition of actual bone and historical narrative.” As seen in the burial and re-burial of Thembu King Sabata Jonguhlanga Dalindyebo (see

G. Dennie 1992), the handling of Kok II’s remains also served as fertile terrain for the articulation of competing political identities, often through contested claims to authenticity or genealogy.

Posel and Gupta (

2009, p. 308) effectively capture this wider dynamic: “The control of corpses is always simultaneously about the social production of life…”

While human remains are the variously disintegrating material traces of deceased individuals, typically buried or otherwise placed out of everyday circulation, their continued existence is often manifest in diverse living, social worlds. In some instances, their exhumations may serve to entrench state power (

Jamar and Major 2022). Likewise, their collection, classification, analysis, and exhibition were central to the development of physical anthropology and scientific racism (

Redman 2016). Yet they can also become part of democratic discourse and discussion. As

Ciraj Rassool (

2015a, p. 155) highlighted, human remains have “featured in debates about the constitution of the new nation of South Africa”, bringing together scientists, transitional justice actors, civil society, and heritage practitioners, amongst others, in processes such as return, reburial, and rehumanization (

Rassool 2015b). Human remains continue to evoke controversy in the post-apartheid era (

Morris 2014, pp. 189–97).

In our analysis, rather than focus on human remains as a pivot point solely in one era and context, we consider how various actors ascribed meaning and drew upon Cornelis Kok II’s bones across a wider period of time, stretching from the ascendancy of grand apartheid in 1961, through to the present day. Rebecca Mancuso and Jeremiah Garsha provide comparable cases from which we take our cue.

Mancuso’s (

2018) offering is a public historical and museological meditation on the preserved fingers of a 19th century murder victim located in a museum in Bowling Green, Ohio. She traces the remains from the lead up to the victim’s murder through to the present day, outlining shifts in political and civic dictates, most directly tied to public historical and curatorial practice. Likewise,

Garsha’s (

2019) microhistorical scholarship on Chief Mkwawa’s skull offers a compelling study of meaning- and myth-making across German and British colonial rule through to contemporary Tanzania.

Garsha (

2019, p. 6) notes that “The journey the skull has undergone, geographic and transformative, is also linked to the long history of reparation and repatriation.” At a much more modest geographic scale, our study similarly traces the “life” of Cornelis Kok II’s bones to show the changing meanings and historical narratives invested in them by various and successive actors, shaped by differing historical moments from the height of apartheid rule in rural South Africa through to post-apartheid advocacy and identity reclamation up to contemporary feelings of postcolonial malaise.

Our work also considers historical shifts in the relationship between technology and society, for as

Stephen Jay Gould (

[1981] 1996, p. 53) notes, “Science, since people must do it, is a socially embedded activity.” There is extensive literature on the history of science and technology in Africa (e.g.,

Hecht 2012;

Mavhunga 2014;

Mavhunga 2018;

Dubow 2006;

McCann 2007). We have found

Giacomo Macola’s (

2016) scholarship on arms in precolonial central Africa particularly apt in the articulation of our approach. Specifically, Macola considers how Africans re-fashioned for their own purposes (or equally importantly, eschewed) an exogenous technology, in this instance, guns, which were reappropriated materially, symbolically, culturally, and politically. Following Macola, we engage with constructivist approaches to technology to recognize how users may repurpose or even innovate a given tool in a way that is independent of its inventor, as well as with material cultural studies to acknowledge the ontological place and role of objects in our social worlds (consider:

Macola 2016, pp. 4–7). We consider how African actors reappropriated an exogenous technology, in this case, paleoanthropological excavation, measurement, and interpretation—a discipline and practice historically tarnished by scientific racism and the racial politics of apartheid (see

Kuljian 2016).

5 At Campbell in 1961, Adam Kok IV reappropriated this technology to solidify his lineage and position, while his grandson, Adam Kok V, continues to draw upon the excavation and its findings for his own political legitimacy. However, Cornelis Kok II’s remains continue to prompt different meanings for various actors depending on their interests and the dynamics of a given historical moment. While some have sought to establish the provenance of Kok II’s remains and, relatedly, Griqua genealogy, to make political claims, we are not so much interested in tracing the debates over social or biological inheritance but rather the nuances in the biography of the bones.

4. Coalition Building, Identification, and Exhumation at the Height of Apartheid Power

In a rural community already deeply shaped by colonial dispossession and as apartheid architects progressively drafted and implemented their racist agendas, a multiracial (though unequal) coalition unearthed Cornelis Kok II’s remains. In 1961, the apartheid state and its ethnonationalist project were in full swing; the economy was humming, and the state was confident and self-assured. The oft-credited architect of apartheid social engineering, Hendrik Verwoerd, assumed the Prime Minister position in 1958 while decolonization and the armed struggle had yet to threaten southern African settler colonial states. In this context, farmer Basil Humphreys, Griqua leader Adam Kok IV, and McGregor Museum archaeologist Gerhard Fock all drew in support and resources from Phillip Tobias and researchers from Wits for the exhumation. But why and how did this team come to be? We first consider the context and possible motivations of the key actors.

Cornelis Kok II’s remains were not the first nor the only ones to be excavated during this time. As the state sought to classify and sort South Africans into immutable racial and tribal categories, much of the contemporary paleoanthropological, and more widely social scientific scholarship, also aimed to trace or establish primordial racial and ethnic origins. Scholars of this era were often trained in a tradition steeped in scientific racism and essentialism (

Dubow 2015).

6 This had political resonance because

volkekunde, a cultural anthropological approach founded on static and essentialist understandings of racial and cultural difference, underpinned state policy and practice (

Sharp 1981;

Gordon 2021). An emerging scholar at the time, Phillip Tobias was beginning to step away from this paradigm towards an understanding of palaeoanthropology grounded in evolution and change over time. While Tobias would later launch a critique of the dominant strain of physical anthropology—a discipline which largely remained in service of apartheid dictates over essentialized racial difference—this was still incubating in the early 1960s.

7 Christa Kuljian (

2016, p. 135) captures this effectively, identifying “…an extreme contradiction between Tobias’s opposition to apartheid in support of human rights and his scientific practices…” Meanwhile,

Saul Dubow (

2006, p. 272) highlights, “Tobias…took some time to reconcile fully his uncompromising liberal political views with the racialized methodology of comparative anatomy within which he was trained.” This dissonance affected his practice.

Kuljian (

2016, p. 150) notes that while Tobias’ personal political beliefs may have been at odds with apartheid race laws, he nonetheless “…offered assistance to various institutions regarding racial classification.” Although liberal in outlook as a citizen, as a scientist Tobias remained bound to the racist norms of his field, scholarly training, and hegemonic professional obligations under apartheid rule.

In the early 1960s, much of rural South Africa remained governed through dynamics of patronage. In the Campbell area, white farmers such as Basil Humphreys served as central power brokers. As employers and landlords, Humphreys and other white farmers wielded wealth and racial privilege in their relationships with the landless, disenfranchised Black and Coloured populace. In some instances, this reached extremes of paternalism such as

baasskap; in others, the relationships could be more complex. Humphreys, an anglophile, distinguished himself from burgeoning Afrikaner nationalist rule, anchoring himself within the preexisting tradition of Cape liberalism (for more on the Cape liberal tradition, see

Keegan 1996). Relatedly, he took great interest in local and regional Griqua and mission history. This was likely linked to his family lineage as a descendant of John Melvill, an agent and missionary associated with the London Missionary Society at Griquatown in the 1820s and later at Philippolis (

Cavanagh 2012). Humphreys conducted research using LMS documents, specifically establishing the authenticity of the Bartlett Church in Campbell, and was keen to promote history locally, having proposed the declaration of the church building as a national monument. This effort is reflected in archival materials and publications (e.g.,

Oberholster and Humphreys 1961) but also in recollections from one of the authors whose family was friends with the Humphreys and who conducted his PhD under the supervision of Basil’s son, Anthony. In short, Basil Humphreys had both the means and the interest to pursue local historical projects. Likewise, as a devout Anglican advancing church work in Campbell (

B. Humphreys 1960), Humphreys engaged personally with and promoted Kok IV, who was also the local Anglican catechist in Campbell’s Griqua community. This took on valences beyond the exhumation, including a monthly donation of a sheep to Kok IV (

Kok 2024, Campbell, Northern Cape, interview by the authors). Humphreys’ relationship with Kok IV and his associated interest in Kok II’s exhumation likely had intersecting personal, historical, and religious motivations.

Humphreys, being a third-generation owner of Bartlett’s lot in Campbell, invested in partial rebuilding and maintenance of what at one time was a run-down skin store on the property, the shell of a 19th century LMS church central to Campbell Griqua history. Brought back into service as an Anglican church in 1947, Humphreys continued the restoration and internal furnishing, and worked with Kok IV who ministered weekly service to his flock at the church.

8 This took on further meaning as with the possible destruction of the existing Griqua burial grounds, which were held on another white farmer’s land, the site of the church became the designated place for reburial. In an unpublished work, Basil Humphreys’ son, archaeologist Anthony Humphreys (

A. Humphreys 2010a, pp. 3, 6), labelled it his father’s attempt to “create a centralised ‘shrine’ to the Griqua community and its history.” Elsewhere, he describes Adam Kok IV as “his [father’s] friend”, with whom he “beautified” the site (

A. Humphreys 2010b, p. 9). While Basil Humphreys’ plans did not fully materialize, the proposed relocation of the graves as well as the designation of the historic church on his property offered a twin motivation to build a hub for Griqua heritage and religious life.

For his part, Adam Kok IV had multiple motivations to support and guide the exhumation of Cornelis Kok II. As described above, he may simply have wanted to salvage what he viewed as his ancestor’s remains from destruction while also wishing to promote the creation of a new site for Griqua history and faith practice. Given his relationship with Basil Humphreys—who could be described as Kok IV’s patron—the exhumation and relocation of Cornelis Kok II also offered Kok IV a further opportunity: he likely, as his grandson does today, viewed the exhumation as a means of securing recognition for his identity and claim to Griqua leadership. Personal, religious, or familial reasons likely motivated him, while the excavation afforded an opportunity to pursue a degree of social mobility in an apartheid society that relegated him as a subject rather than citizen. The excavation also offered a means to provide certainty to his lineage and legacy; knowingly or unknowingly pursuing a path to historical recognition that, given the dynamics of rural patronage, could lend itself to distortion. We cannot know definitively. He may simply have viewed the exhumation and proposed relocation as a means to construct an enhanced place of worship for his flock.

There may have been another political factor at play for Kok IV and his followers. According to Anthony Humphreys (

A. Humphreys 2010a, p. 5), “Griqua identity was held in high esteem in Campbell; they regarded themselves as being ‘higher’ in the social order than ‘ordinary Coloured people.’” This was possibly emphasized in Kok IV’s relationship with Basil Humphreys. The exhumation offered a tool to reject the apartheid imposition of simply a Coloured identity and as a means to restore a frontier heritage cast aside by the white supremacist regime. As in the case of earlier 20th century Griqua leaders, Griqua and Coloured identities could coexist (

Cavanagh 2011, pp. 10–11), though starting from the 1970s, some sought to distinguish the two identities; this dynamic shifted again with post-apartheid assertions of Khoisan heritage as the Coloured political designation “lost much of the…[relative] value it previously conferred…” (

M. P. Besten 2006, p. 11). In 1961, for Kok IV and his followers, the desire to uphold a Griqua identity likely reflected a feeling that the disenfranchised community felt unmoored from their place, history, and heritage.

The exhumation then was something of a paradox; while contoured by the dynamics of apartheid policy and logic, in practice, it demanded a multiracial coalition. Quite simply, it would not have been possible to pursue without Kok IV’s stewarding the research teams. However, there is an ambiguity in the actual identification process, as one contemporary report claims that Kok IV misidentified Kok II’s headstone when compared with the testimony of multiple elders (

B.F.B. 1961a, June 3). Regardless of Kok IV’s immediate motivations or accuracy in locating Kok II’s headstone, by playing a key role in the exhumation, his actions show that it offered him an opportunity to affirm identity and status for both himself and the Campbell Griqua. Today his grandson, Adam Kok V, continues to draw on this event for his own recognition as a Griqua leader, noting that it offered “certainty” about his ancestry (

Kok 2024, Campbell, Northern Cape, interview by the authors). In this instance, for Kok IV, the event constitutes a reappropriation of technology (archaeological excavation and physical anthropological analysis) towards identity affirmation and cultural meaning within his own context. As Adam Kok V relates, the excavation, for Kok IV, “allowed him [Kok IV] to see how he was related…” (

Kok 2024, Campbell, Northern Cape, interview by the authors). It offered Kok IV a means to situate himself to the land of his claimed ancestors as well as to his followers and to outsiders as the rightful heir of Griqua cultural memory and leadership.

Leveraging this technology towards Kok IV’s ambitions demanded an interracial collaboration brokered by his patron, Basil Humphreys. While the exhumation could not have occurred without Kok IV, it was also a process far from his control. During the excavation itself, Humphreys appears to have been the major power broker. Phillip Tobias was keen to conduct the exhumation as he was reportedly interested in the burial site of Kok II and other Griqua notables for broadly anthropological reasons; the geological features of the site lent themselves to uniquely optimal preservation of 19th century human remains (

B.F.B. 1961a, June 3). While Tobias and his team of Wits researchers went on to disinter 34 other Griqua remains between 1961 and 1971 (

A. Humphreys 2010a), the unearthing of Cornelis Kok II’s remains fell principally to McGregor Museum archaeologist Gerhard Fock and Basil Humphreys, with Tobias lending a hand. It is likely that Humphreys’ role was largely in organizing, observing, and contextualizing the excavation.

A local newspaper report indicates that Adam Kok IV’s son, Abraham Kok as well as community member Neels Watermond assisted in the exhumation, while Kok IV himself observed the proceedings. Upon identifying the grave as likely that of Kok II’s, the local newspaper report claims Kok IV

…rose from the large drum of plaster-of-paris on which he had sat most of the afternoon and in company with amateur and professional photographers and seemingly half the population of Campbell, stood at the grave edge to see the first sight of his illustrious forebear who had been buried almost exactly 103 years before.

At this stage, Phillip Tobias is alleged to have confirmed that the skeleton matched the characteristics of a roughly 80 year old man, thus affirming the remains as Kok II’s, and equally important, Kok IV as his descendant (

B.F.B. 1961b, June 4).

9 Consensus was quickly reached that this was indeed likely Cornelis Kok II’s grave and human remains. Gerhard Fock noted that this grave was “distinctly different from the others. It seems to be a Christian burial in a coffin and the coffin indicated that it was a person of great importance” (

Fock 1961).

According to contemporary newspaper reports, Kok II’s remains were intended to undergo “up to two years…[of] experiments, tests, and investigations…[before being] reinterred in Campbell” (

B.F.B. 1961b, June 4). This is reinforced by the fact that Cornelis Kok II’s exhumation was intended for relocation and reburial rather than research, as indicated by the grave relocation permit (

B.F.B. 1961a, June 3). However, as it would turn out, Kok IV, and more broadly, the Campbell Griqua community, lost all control over the fate of Kok II’s remains until after the election of a new post-apartheid government more than three decades later in 1994. In the interim, Phillip Tobias and Wits had taken effective ownership of the assemblage. While some later claimed that these remains were relegated to “secret” or racially segregated holdings—what one activist called a “‘Whites Only’ closet”—this remains contested (

Diamond Fields Advertiser 1996;

Engelbrecht 2002, p. 243;

Morris 2022, p. 237;

A. Humphreys 2010a, p. 5). Regardless, the remains stayed domiciled at Wits until a 1996 ceremonial handover and later a reburial in 2007; these events were also shaped by contemporary political dynamics that drew on shifting contours of historical and cultural memory as well as global and national civil society.

5. Post-Apartheid Contestations over Kok II’s Remains

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Cornelis Kok II’s remains lay at Wits without public challenges or calls for their return. While the continued stay of the remains likely was a sore point for the family and community, it is unclear why this controversy lay dormant through this period; it is possible that quite simply, particularly following Adam Kok IV’s 1978 passing, the community had more immediate, pressing issues. However, this changed in the 1990s with the advent of post-apartheid democracy and a new constitutional order, of Griqua interaction with global civil society, as well as the emergence of Khoisan identities. Accordingly, Griqua and Khoisan identities quickly became entangled, and often conflated, with representatives of the former emphasizing heritage from the latter. Cornelis Kok II’s remains became a fulcrum for claiming these identities and related positioning in post-apartheid South Africa as indigenous peoples.

Indeed, in 1997

Bank and Minkley (

1997, p. 3) noted what was then a recent shift “towards interpreting Khoisan history…primarily in terms of a project of cultural retrieval.”

Linda Waldman (

2007) suggests that the adoption of indigenous identities was driven by a perception of marginalization at the hands of the post-apartheid government. Michael Besten (

M. Besten 2009, p. 134) notes this broader “shift was largely motivated by an attempt at finding identity terms” in support of “broader coloured social and political concerns rather than those of people who had historically espoused Khoe-San identities.” Griqua identity was central to this. As Coloured identity became destabilized in the democratic era, embracing a Khoisan identity, in some instances alongside claiming Griqua-ness, offered a means to re-fashion one’s self and collectively in order to “outdo Bantu-speaking Africans in claims to indigeneity and entitlement to resources in South Africa” (

M. Besten 2009, p. 167; also see

Msimang 2021, pp. 250–51). Nonetheless, this constituted a major shift from earlier decades; for instance, in the 1970s, one scholar identified only two families in Campbell who “acknowledged San (Bushmen) descent” (

Nurse 1976, p. 280).

10 While members of the community may have had their own reasons for not claiming this lineage in the 1970s, nonetheless, in the post-apartheid era, Cornelis Kok II’s remains quickly became a flashpoint for claims of belonging that drew upon and produced cultural memory in service of an emergent indigenous peoples’ political identity. Quite simply, activists repurposed human remains in the first decades of a democratic dispensation forged by political compromise, which both promoted individual rights while giving credence to group rights and group self-determination operating at a sub-national level within a unitary state (

Oomen 1999, pp. 73–103). Authority over the bones offered purported ownership of a deeper memory in service of often “totalizing” contemporary ethnic and cultural identities (

S. Robins 1998).

Activists made calls for the return and reburial of Kok II’s remains grounded in a claim to Griqua dignity developed alongside overlapping, emergent, more encompassing identities as “Khoisan” and “First Nations”. These were often predicated on a notion of having been silenced under colonialism and apartheid as well as fears of marginalization in the new dispensation. These identities were often grounded in biological or historical claims to autochthony, to antedating the rest of South African society (

S. Robins 1998). This dynamic simultaneously took the form of political fragmentation and politicking, both reflecting the dispersed nature of Griqua communities and identity but also the new civic space for interest-based advocacy and claims to representation. For instance, in April 1996, the Griqua National Conference of South Africa (GNCSA)

11, itself with roots deeper into the 20th century (

Cavanagh 2011, p. 11), responded to a major exhibition by Pippa Skotnes entitled

Miscast, which sought to shed light on Khoi and San history and heritage. GNCSA quickly lambasted Skotnes, claiming that

Although alerted by the GRIQUA to the indigenous people’s rights movement…she has failed to include this vital dimension…Ignoring the universal quest by indigenous peoples worldwide (known as the FOURTH WORLD) for their democratic accommodation and re-empowerment…following centuries of colonially-engineered genocide.

This cross-identification as indigenous peoples took a stronger valence over human remains, particularly after the 1996 symbolic return of Kok II’s remains to Kok V. Expressing outrage, the Conference released another statement: “We will never relinquish our rights to exist as GRIQUA and descendants of the KHOISAN” (capitalization in original (

Griekwa Nasionale Konferensie van Suid-Afrika 1996a)). The GNCSA further claimed credit for the return of Kok II’s remains while also “…demanding the return for burial of the GRIQUA remains of the late Miss Saartjie Baartman and the ending of all dehumanised portrayals of the KHOISAN ancestors of the GRIQUA…” Labelling themselves as an “indigenous

First Nation of South Africa”, they demanded to participate in constitutional negotiations “as

equal partners with the

nation-state government” (underlining, capitalization, and italics in original (

Griekwa Nasionale Konferensie van Suid-Afrika 1996a)).

The GNCSA directly connected their own appeal to representation of the Griqua, and by extension, a wider, “uninterrupted” Khoisan heritage and community. In 1997, Alan Morris (p. 117) noted that this intensely elevated “one aspect of origin at the expense of the other cultural and biological sources…the Griqua better represent a union of diversity rather than a repository of cultural purity.” The homogenization of Griqua identity or the GNCSA’s move to “seriously overemphasize” Khoikhoi origins may also reflect the projecting back in time of colonially constructed identities that while legible and indeed, usable, in the present, may not accurately reflect historical realities (

Morris 1997, p. 117;

A. J. B. Humphreys 1998). Indeed, borrowing from

Zadie Smith (

2020), this may constitute an instance of “‘over-writing’…[when] one story [is] overlaid and thus obscuring another…” In short, the homogenization of Griqua history lends itself to mystifying the past; this can be politically productive, offering a clearly legible ethnic identity (and story) to be wielded in and recognized by the marketplace (

Vail 1989;

Comaroff and Comaroff 2009;

Schweitzer 2015). The GNCSA levelled their appeal and claimed the capacity to represent Griqua communities against their chief rival: Adam Kok V. The return of Cornelis Kok II’s remains served as fertile grounds for factionalism.

The GNCSA derided Kok V as “the self-styled ‘

chief’ Adam Kok V”, and part of a cohort of “

Johnny-come-lately fifth columnists, agent provocateurs, and cuckoo nest-operators” who they claimed “are not, and never will be, recognized by the majority of GRIQUA” and thus should not have been granted the remains (italics and capitalization in original (

Griekwa Nasionale Konferensie van Suid-Afrika 1996a)). Simultaneously, the organization used the event of the symbolic return to identify as participants in the global indigenous rights movement in the “14th session of the United Nations

Working Group on Indigenous Populations” (italics in original (

Griekwa Nasionale Konferensie van Suid-Afrika 1996a)) to stake out overlapping identities as Griqua, Khoisan, and indigenous peoples, while also assuming a gatekeeper role against Adam Kok V. Cornelis Kok II’s remains served as a touchstone for political factionalism, indigenous peoples’ mobilization, diverse assertions of identity, and multiple claims of representation.

For his part, Kok V also used the symbolic return of the remains to position himself in post-apartheid parlance of social justice and recompense. A newspaper report (

Diamond Fields Advertiser 1996) following the return frames Kok V as having “lambasted Wits University for taking him [Cornelis Kok II] in the first place” while also calling for a “middle ground…to allow for research without the humiliation of our ancestors.” Citing the material conditions of his followers, Kok V reportedly called for land restitution and financial compensation: “I will not allow the continued humiliation of our people at Campbell.” Finally, he included a reconciliatory note, stating, “We appreciate the positive spirit with which Wits University agreed to the return of the remains of our ancestor” while condemning the initial “humiliating and blasphemous act” of the excavation (

Diamond Fields Advertiser 1996). In this instance, Kok V positioned himself as the rightful heir in both magnanimously accepting Kok II’s remains while casting the initial excavation as part of apartheid exploitation and indignities, an expression that was newly enabled and encouraged in the immediate post-apartheid moment. In doing so, he affirmed his position tracing himself to the human remains using the political and cultural imperatives of the moment.

For his part, Phillip Tobias positioned himself and the symbolic return of Kok II’s remains as something of a closure. This framing both aligned with wider dictates of post-apartheid reconciliatory sensibilities and closed what may have been an awkward, even shameful chapter in his own professional life.

Christa Kuljian (

2016, p. 139) notes the striking absence of Tobias’ time in Campbell from his later retrospective work; he may have embraced these proceedings to bookend an initiative that, both with hindsight and shifts in his political and scientific approaches as well as the political moment, sat awkwardly. As

Kuljian (

2016, p. 226) notes, during the 1990s, Tobias “had the opportunity…to reshape his reputation” to meet the new political moment yet he also remained protective of the scientific tradition that he both came from and historically operated within. The event may have allowed him also to settle or at least put away a lingering source of discomfort.

Nonetheless, in the speech he delivered at the 1996 handover ceremony, Tobias outlined the basic contours of the exhumation and his relationship with Kok IV. He concluded it by returning to a language of obligation, maintaining that he had Kok IV’s “very warm support in all of this work and it was with his full blessing and approval that we undertook it.” He adds that he too made a promise to Kok IV: “I said when we had finished, we shall return the bones of Cornelius Kok II [sic] to Adam Kok IV and the time has come for me to honour my promise. It wasn’t in writing, it was a by word-of-mouth promise from me to the captain” (

Tobias 1996).

12 In doing so, he captured the zeitgeist of the immediate post-apartheid moment: an individual relationship, an intimate episode, a shared obligation finally made right. By this time, Tobias had projected himself as an icon of white liberalism, with scholarship challenging apartheid orthodoxy on race (e.g.,

Tobias 1972). In fact, in 1999, he would be recognized as an emblem of the new South Africa when Nelson Mandela awarded him the Order of the Southern Cross—one of the final recipients of a recognition previously tarnished by apartheid.

At the 1996 repatriation ceremony, while not his focus, Tobias further aligned with the post-apartheid proliferation of assertions to Khoisan identity. During his speech, he lamented the “lack [of] major works about the Khoisan in general and the Griqua people in particular, by representatives of the people themselves so that the history may be seen from the viewpoint of the communities themselves” (

Tobias 1996). His statement reflects the rise in interest in Khoisan identity and history, alongside the imprint of social history and community archive projects that characterized late apartheid South Africa and the first years of democracy (consider

Legassick and Minkley 1998;

Witz 2019). However, indirectly, he affirmed his role in cementing who constitutes the “representatives of the people” as a scientific authority.

The symbolic 1996 handover ceremony became a reflection of the moment with two competing Griqua representatives’ self-positioning, using idioms forged both in national and global cultures, while the celebrity white scientist took the opportunity to largely bow out and anchor the return in reconciliatory language. Largely due to conflict between Wits and Adam Kok V over who would foot the bill for relocation and reburial (

Kuljian 2016, pp. 225–26), Cornelis Kok II’s remains continued to stay at Wits until the 2007 reburial when they again evoked controversy and political contestation.

6. Contested Closure: The 2007 Reburial of Cornelis Kok II

On 23 September 2007, Cornelis Kok II’s remains, along with the remains of 34 others were, for the second time, laid to rest.

13 However, this was not without controversy. Following the initial 1961 reburial plan, the remains were interred at the Mission Church Precinct, where the Campbell Griqua church is located. The formal programme included faith leaders, politicians, as well as members of Adam Kok V’s Campbell Griqua community (

Reburial Service of the Late Kaptein Cornelius Kok II 2007). Phillip Tobias was unable to attend (

Tobias 2007). Unplanned interventions also marked the occasion, when Johannes Younger, a competing claimant to Griqua leadership dramatically staged a protest.

Armed with a rival Griqua organization’s flag, Younger disrupted the ceremony before being forced to withdraw (

onttrek). Newspaper reports from the time frame him as then moving to the entrance of the event where he “staged a peaceful protest” (

Younger het ‘n vreedsame betoging by die ingangshek gehou). Visibly aggrieved (

Beswaarde), Younger became upset that, in his rendering, the flag was forbidden. In describing the symbolic meaning of the flag’s aloe iconography and colours, Younger attempted to explain the richness and diversity of Griqua history and heritage both within and beyond the Northern Cape. In so doing, he offered an indictment and protest at the exclusion of wider Griqua networks from consultation and participation in the reburial proceedings (

Coetzee 2007). In this instance, Younger’s protest offers another highlight of Griqua factionalism, albeit contoured by Griqua nationalism rather than wider appeals to identities as indigenous peoples or Khoisan.

Unable to attend the reburial (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), in a letter to Adam Kok V, Phillip Tobias reaffirmed both the merit of the initial excavation as well as the Griqua’s increasingly important claim to Khoisan identity. In the first instance, Tobias wrote that Kok V’s grandfather, Adam Kok IV, “had asked me” to prove the provenance of Cornelis Kok II’s grave, as well as to “throw light on the history and make-up of the Griqua nation, which at that time was something of a mystery…even to the Griqua people themselves” (

Tobias 2007, pp. 1–2). He further celebrated a study conducted by his former PhD student, Alan Morris, which was enabled by the initial excavation—and implicitly, by keeping the remains at Wits.

Tobias (

2007, p. 2) noted that his former pupil’s study demonstrated, that “…this [the Campbell] Griqua population was largely KhoeSan [sic] in its genetic make-up…confirmed by human genetical [sic] studies on blood samples from the living peoples of Campbell.” However, the findings also implicitly harken to the frontier past and subsequent histories of migration. As

Tobias (

2007, p. 2) noted, “…there were [also] some strong indications of genes from white and black individuals.” Nonetheless, the emphasis on highlighting the Khoisan heritage and genetic makeup of the community provided a degree of legitimacy for Adam Kok V and a scientistic resource, which, as we will see, continues to suffuse his claims for recognition and material standing. It turns out, the reburial itself left much to be desired.

7. Not at Rest, Again: Continued Unease, Anxieties, and Utilities of Cornelis Kok II’s Remains

In November 2024, we paid a visit to Adam Kok V. He and his family welcomed us into their home. He was quick to highlight a few interlocking claims. He brought out a copy of the speech made by Tobias at the 1996 handover ceremony and expounded on his grandfather’s role in the initial exhumation, mentioning specifically that Kok IV had “asked them to dig up the grave”. Kok V added that the excavation and scientific inquiry continues to offer an affirmation of his lineage as a Griqua leader. He similarly criticized other competing claimants to the title, reflecting the persistence of factional divisions amongst Griqua communities, charging that others “make assumptions that they are the rightful heirs”, and slamming his competitors’ motives, that for them, “…it’s all about kingship.” Similarly, he lamented what he felt was the continued marginalization and lack of recognition of both Griqua and Khoisan peoples and leadership structures: “all the other groupings are getting what they need…but we never get it” (

Kok 2024, Campbell, Northern Cape, interview by the authors). However, many of his concerns also fell on something much closer to home: the state of Cornelis Kok II’s reburial site.

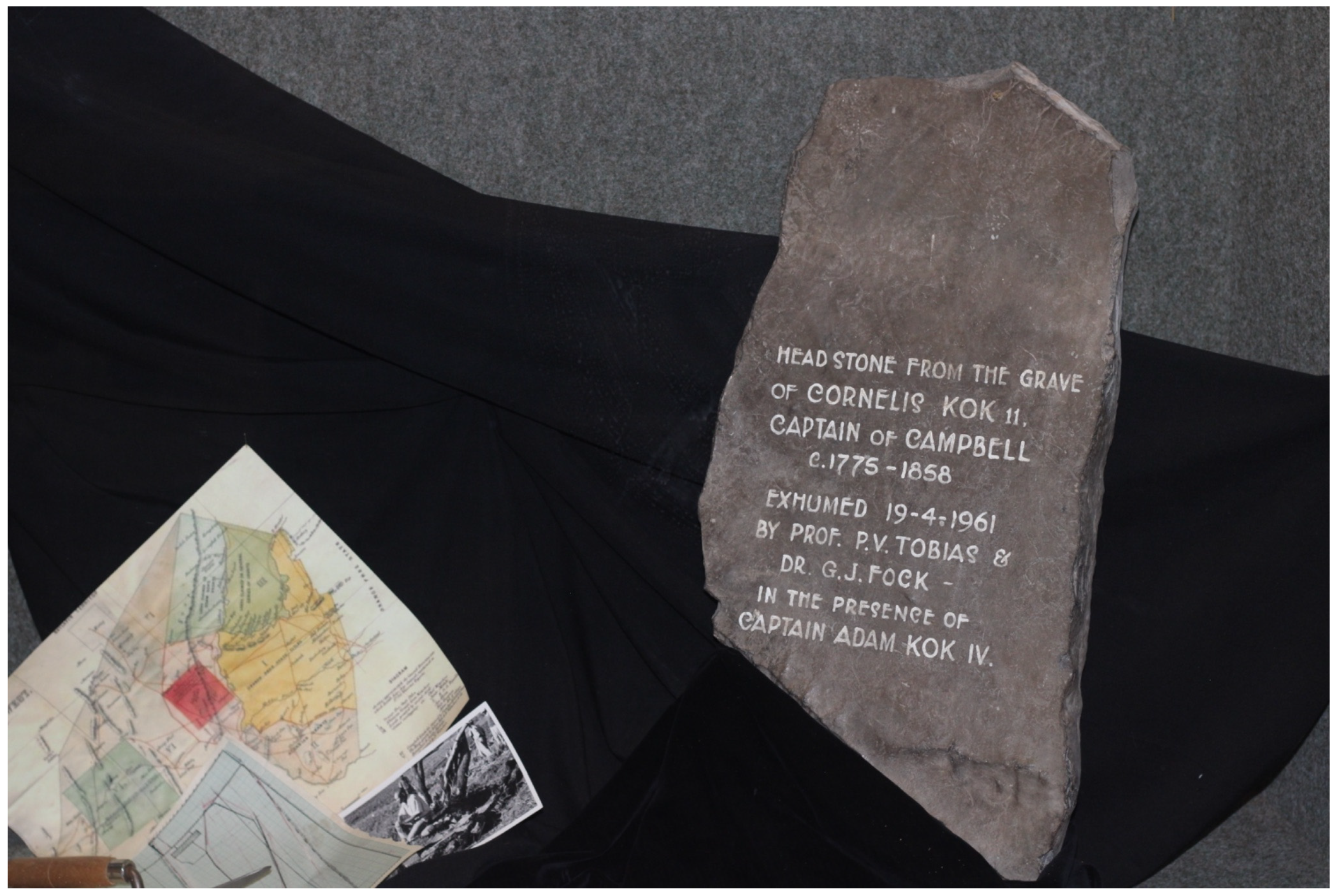

As Kok V noted, the reburial was conducted, “with dignity, but the dignity stops there…there was silence after that.” He further laments that the Griqua community does not have control over the property where the gravesite rests, as well as the poor state of the graves. There is no tombstone. He suggested one possibility to replace the tombstone is to return a previous one now hosted by the McGregor Museum (

Figure 3). Further noting the disrepair, he suggests that the government must meet with him, particularly the newly minted Minister of Arts and Culture Gayton McKenzie.

14 Insisting on the debt owed to his community, “the Khoisan people”, he anchors his claim in post-apartheid political culture (

Kok 2024, Campbell, Northern Cape, interview by the authors). For Kok V, the “silence” after the reburial reflects the failures of government, a common feeling amongst many denizens three decades into South African democracy. Meanwhile Kok V’s claim remains contoured by an ethnicized appeal, fitting within a wider dynamic where in the ashes of the promises of social democracy claims to a marginalized group identity dominate as a means to access resources (

Neocosmos 2016, pp. 428–29). Indeed, ethnic identities inherited from the colonial and apartheid eras continue to hold social relevance and at times, command economic resources and degrees of subnational political sovereignty. Some activists brand government policies that promote hierarchical conceptions of traditional governance and ethnic belonging as “Bantustan Bills” in reference to apartheid-constructed tribalism (see

Alliance for Rural Democracy 2024).

For our part, upon visiting the graves, each of us was struck by the state of the site. This is both a function of the insensitively planned layout and failure to maintain upkeep. For instance, the toilets built for church-goers and visitors are directly adjacent to the grave (

Figure 4). We also noticed the lack of signage and commemorative materials. Moreover, the church itself lacks electricity after the theft of its electrical fittings and its roof begs rethatching. There appears to be little to no state support for the site. While it is unlikely that the state aims to “silence” this history, the condition of Cornelis Kok II’s grave and surrounding heritage site reflects the failed promises of democracy where commitments have been made, but not necessarily sustained with dignity. This is likely exacerbated by factionalism amongst organized Griqua entities which undermines effective political mobilization. Nonetheless, the neglect of Kok II’s grave stands in for the anxieties and fears of exclusion from post-apartheid public culture and a place in the democratic political order felt by many Griqua leaders during the country’s political transition, and expressed by Adam Kok V today.