1. Introduction

The Jukes: A study in crime, pauperism, disease, and heredity was originally an investigation of the influences of heredity and environment but led to one of the most well known of the eugenic family studies, cementing the infamy of the Juke family. Their true identities were hidden behind pseudonyms and the developing mythology, as the narrative of the genetically problematic family was being created. Its genesis can be found when members of the ‘Juke’ family, well known to the New York prison service, became the subject of a study published in 1877 (

Dugdale 1877). The oft-repeated facts claim R. L. Dugdale traced 1200 individuals, over a timespan of 75 years.

1 Max has often been wrongly described as the founder of the Juke family. Instead, Dugdale had noted that he was of Dutch descent, a back-woodsman type, and two of his many sons married two sisters of the Juke family (

Dugdale 1910, p. 14). The descendants proved to include an abundance of paupers, criminals, prostitutes, and sufferers of venereal diseases. He suggested that their social dysfunction was the result of heredity and environment (

Engs 2005, p. 47). Notoriety came quickly, with the eugenics movement initiator Francis Galton calling them an ‘extraordinary example’ in 1883 as he argued the connection of the criminal with the hereditary (

Galton 1883). In this way, eugenic propaganda repurposed the Jukes study as an example of inherited criminality. In the 1910s the study was revisited by the American Eugenics Review Office. Researcher Arthur H. Estabrook retraced the work and extended the family tree down to 1915. Estabrook’s work was made possible after some of Dugdale’s papers were found in the Prison Association cellar. Dr. Lewis, General Secretary of the association, gave permission to the Eugenics Record Office to copy the names and other unpublished material.

The publication of this rewriting of the Jukes story helped precipitate the spread of eugenics in North America (

Estabrook 1916). He presented the Jukes as an example of defective inheritance, where physical, mental, and emotional characteristics were passed on to the detriment of society. They were an example of the fertility of the feeble-minded and a powerful example of why they should be prevented from ‘propagating’. (

Engs 2005, p. 53). The eugenic narrative of inheritable traits was effective because it was simple. The layman was easily able to grasp the lore of heredity: ‘like begets like.’ They understood that each species produced its own kind. Eugenic educational material included pedigree charts constructed to show the heredity origins of social problems (

Lombardo 2001, p. 247). This appeared to offer a scientific solution to antisocial behavior.

Critiques of eugenics as a pseudoscience maintained public awareness of the Juke family study. Scott Christianson, an investigative journalist, wrote a

New York Times article “Bad Seed or Bad Science?” which appeared in February 2003. This followed the 2001 rediscovery of the Ulster County poorhouse graveyard and its associated records. Christianson reported that Estabrook’s code book had been located. This book identified those the researchers had hidden behind pseudonym first names and code numbers. Max, the ‘founder’ of the Juke family, was identified as Max Keyser. The woman commonly identified as ‘Ada Juke’ or ‘Margaret, the Mother of Criminals’ was ‘Margaret Robinson Sloughter.’ More recently, Robert Jarvenpa has written about how he came across Estabrook’s papers in 1986 in the M. E. Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives of the University Library at SUNY–Albany. He describes the files as including a lengthy list of people, their residences, statistics, and character profiles along with their numerical codes (

Jarvenpa 2018, pp. 19–20). However, Jarvenpa’s interest was in race rather than investigating the foundations of eugenic studies, and he did not pursue the topic.

For this study, the original code book has not been consulted, as the privacy restrictions placed on access would then preclude revealing the actual identities of the family members studied.

2 The original study took place in the 1870s, and the Juke sisters were believed to have been born between 1740 and 1770. Dugdale’s research took place at least one hundred years later, and Estabrook’s another forty beyond that. Despite this, there is an ethical responsibility in revealing the real identities of the Juke sisters. The article by Thomas Daniel Knight in 2024 draws attention to the genealogical researcher’s ethical responsibility of the genealogical researcher to be sensitive to the people studied and respect them as unique individuals (

Knight 2024, p. 78).

This study first explores how eugenic family studies have been re-evaluated. It then analyses how the Juke family was created by Dugdale and re-examined by Estabrook. This article then re-evaluates the Juke sisters by using the material in the public domain to locate their true identities. In doing so, this article contributes to the re-evaluation of family studies, finding, as others have done, that the eugenics movement utilized the developing science of genetics to support a political agenda while sometimes manipulating evidence to do so.

2. Reexamining the Family Study

To say that the Juke family study has been widely known is an understatement. Dugdale’s book has been cited in work in the fields of criminology and criminal behavior, special education, welfare policy and public health, disability, mental health, and psychology. From the 1910s, eugenicists relied on the genre of published family studies when promoting eugenic solutions to persistent social issues. The revised Juke family study described the generations of moral degenerates and criminals that emerged when the ‘feeble-minded’ were allowed to ‘propagate.’ It was part of a genre, one Nicola Hahn Rafter reviewed in her important contribution to the literature, a collection of eleven influential American family studies that included the Jukes (

Rafter 1988). Rafter demonstrated that such studies were characterized by researcher biases, stereotyping, and a rudimentary understanding of the developing science of genetics (

Rafter 1988, pp. 22–25). She analyzed the literary devices used to create the eugenic narrative, including language that enhanced an ‘us-other’ perspective. Her work was not a re-evaluation of the factual basis of any family study, although she noted study authors were not above improving the facts with a little manipulation (

Rafter 1988, p. x).

Social historian David Smith was the first to seriously challenge a family study. He looked at Henry Goddard’s 1912 family study on hereditary degeneracy in 1985, specifically Goddard’s narrative about the Kallikak family (

Smith 1985). Smith’s research revealed that the founder of the ‘bad’ Kallikak line was actually a literate, land-owning man, contradicting Goddard’s degeneracy claims (

Smith 1985, pp. 91–93). In 2009, Nathaniel Deutsch’s book revisited another family study, finding normal family histories and exposing how previous reworkings misrepresented the family’s origins to support racial arguments (

Deutsch 2009). These misrepresentations show the political use of supposed scientific research. Smith and Michael Wehmeyer’s 2012 article further debunked Goddard’s work by identifying flaws in the Kallikak family genealogy (

Smith and Wehmeyer 2012, p. 8). They showed that Goddard had relied on inaccurate accounts, and the supposed illegitimate birth central to his argument was fictional (

Smith and Wehmeyer 2012, p. 10). Instead, the family’s history revealed a more common experience of economic vulnerability, not hereditary feeblemindedness.

In addition, the methodology of eugenic family studies has been critiqued. Paul A Lombardo is one of those making general critiques, calling it ‘propaganda that reduced science to simplistic terms’. (

Lombardo 2001). Similarly, John Macnicol called the methodology ‘crude and the genetic evidence unconvincing’ (

Macnicol 1987, p. 297). Recently, Andrea Ceccon has looked at how the material on the Juke family was presented (

Ceccon 2024). She argues that the Juke family study was important in cementing the authority of the Eugenics Record Office methodology in eugenic studies.

So far, no published academic study of the real Juke family has been published. Elof Axel Carlson is the acknowledged expert on the Juke family, as, in 1980, he refuted the way Dugdale’s original assertions were reinterpreted by subsequent authors, including eugenicists (

Carlson 1980). He emphasized Dugdale’s environmental focus and arguments for social improvements to elevate the lives of the less fortunate. This was a reassessment of Dugdale’s position that had been lost in the Eugenics Record Office’s revision of the Jukes family, rather than an examination of the family behind the Juke name. Carlson also included the Juke family in the central argument of his 2001 book

The Unfit: A History of a Bad Idea. Again, he did not look at the identification of the Juke family members.

The proliferation of primary sources accessible online allows an investigation to uncover the identities of the Juke family, in particular, the women described as five of the six Juke sisters. The church and prison records upon which this type of investigation must be based are currently available online through a range of providers. The location of the Juke family in Ulster County meant that research first focused on Margaret Robinson Sloughter’s family, which was located in Marbletown. Marbletown church registers were found through Family Search (

https://www.familysearch.org/en/search/catalog/results?q.place=Marbletown%2C%20Ulster%2C%20New%20York%2C%20United%20States, accessed 3 April 2025). This site also provides access to records from other nearby towns. The Library of Congress website enables access to the book

Baptismal and Marriage Registers of the old Dutch church of Kingston, Ulster County, New York, which covers 1660–1810. This volume includes information that ‘the early Dutch were accustomed to having their children baptized a few days after birth.’ Ancestry has a source called “Dutch Reformed Church Records in Selected States,” which includes both New York and New Jersey. Ancestry also provides access to New York state prison records, which, when used in conjunction with Dugdale and Estabrook’s charts, help untangle a complex family tree.

The Juke family study, like others, has been subject to reinterpretations by authors to support their agendas. A more complete investigation helps to understand how family studies were first created to sustain the narratives of their authors.

3. The Story of the Jukes

The Juke family had its origins in the New York work of the Prison Association. Dr. Elisha Harris, a member of the Prison Association, was instrumental in dispersing the story of Margaret, the Mother of Criminals (Arizona Sentinel, 9 May 1885, p. 4). He first spoke to the New York Charities Aid Association in December 1874 (Republican Journal, 31 August 1876, p. 1). His description of Margaret was as a pauper child, left to fend for herself ninety years earlier, given some charity but never educated or given a proper home. In January 1875 he included her story in his report on prison visitations to the Legislature (Martinsburg Weekly Independent, 16 January 1875, p. 3). Then in March 1875 the report of the Charities Aid Society referenced one sister; ‘The sister of the original Margaret is known in the medical history of the county during the time of the Revolution as having been one of the most dissolute persons ever known in the region.’ (Commercial Advertiser, 18 March 1875, p. 1).

The early newspaper reports then show that Margaret was connected to two other similar girls. An 1875 account was already twisting the narrative, reporting that the three ‘were mere children themselves when they began to bear illegitimate children. Margaret was the most prolific of the three, but they were all human rabbits.’ (Grant County Herald, 8 April 1875, p. 1). The story of the ‘mother of criminals’ was used by the State Charities Aid Society to argue that the interbreeding of degenerate stock was filling the reformatories and refuges of the state. Similarly, Margaret’s story was used in a Chicago newspaper to argue for compulsory education of children, presenting her as ‘a little waif,’ orphaned or abandoned by her parents (Grant County Herald, 8 April 1875, p. 1). Exploiting and sensationalizing the lives of those on the social margins is a theme that would be repeated in this and other eugenic family studies.

Dr. Harris cited the research of Richard Dugdale. A sociologist, Dugdale started in the New York Prisons, looking for examples of multigenerational criminal careers as a volunteer inspector for the Prison Association. He appears to have found only one example. It was in Ulster County, although unnamed in his narrative, that he found six people with familial links, although they had four different family names (

Dugdale 1910, p. 7). He then proceeded to uncover their criminal relatives and to fill out an initial family tree of 100 people. In doing so, he found enough evidence to convince him that Margaret was the common link and the origin of this defective family.

Dugdale’s depiction of a group of families that did not labor consistently, and instead appeared to rely on criminal activities and charitable aid allowed them to be viewed as different and as separate from mainstream American society. The name he gave to this family grouping added to the impression of otherness. Carlson cites A.E. Winship as giving the probable origin of juke as a slang term for the haphazard manner of roosting in fowls (

Carlson 1980, p. 535). Nathaniel Deutsch’s argument about the name given to the subject of another family study, that it was intended to subtly stigmatize by playing on contemporary ideas of threat, could also apply here, as social stability was perceived as threatened by transients (

Deutsch 2009, p. 5).

Although the newspaper accounts of the initial findings had only alluded to three girls, during his research Dugdale located other women that he included as sisters to Margaret (his ‘Ada’). It is apparent that Dugdale, who researched people born more than a century earlier, had not found evidence of the parentage of these ‘sisters’. It has always been clear that Dugdale did not adequately investigate the parents of the Juke sisters. He wrote the following:

Between the years 1720 and 1740 was born a man who shall herein be called Max. He was a descendant of the early Dutch settlers… He had a numerous progeny, some of them almost certainly illegitimate. Two of his sons married two out of six sisters (called “Jukes” in these pages) who were born between the year 1740 and 1770, but whose parentage has not been absolutely ascertained. The probability is they were not full sisters, that some if not all of them, were illegitimate. The family name, in two cases, is obscure, which accords with the supposition that at least two of the women were half-sisters to the other four, the legitimate daughters bearing the family name, the illegitimate keeping with the mother’s name or adopting that of the reputed father.

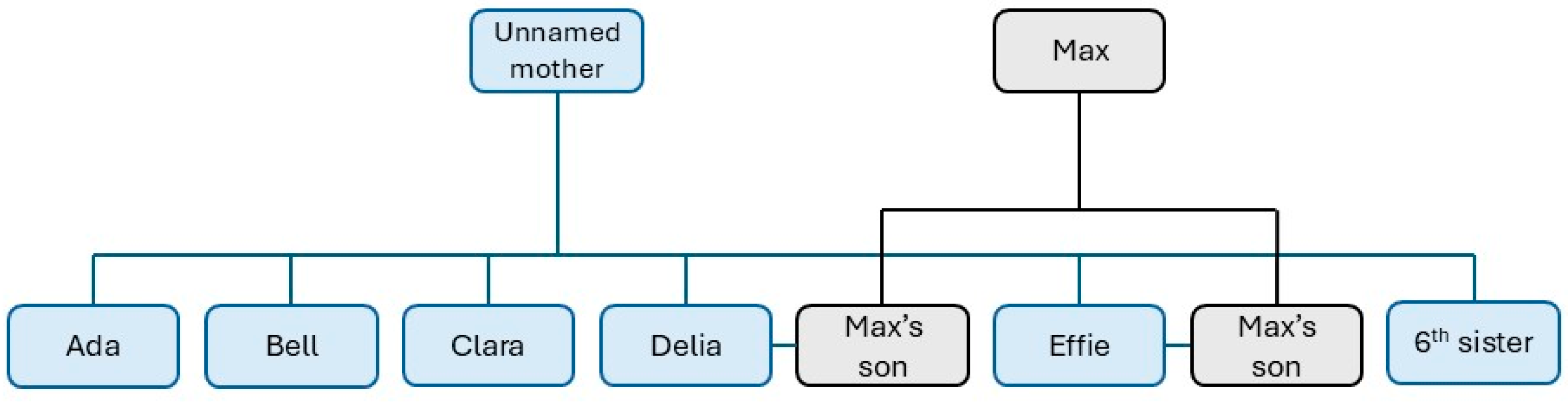

The relationships Dugdale describes can be seen in

Figure 1, with the six sisters of the unnamed woman and the marriages to Max’s sons. As a family tree, it lacks essential detail, the impact of the time elapsed since the sisters’ births and the lack of accessible records in Dugdale’s time. Both had a significant impact on Dugdale’s ability to produce accurate historical research, despite the quality of his research in his own period. He had some women linked by a common surname and two women who had another surname or surnames. His admission that he had been unable to trace one woman who had ‘moved out of the county’ demonstrates that his research was limited to the local area. His interpretation of the information received led Dugdale to assume that the Juke sisters’ surnames meant some were illegitimate. He did not consider that there might have been identity confusion, where one individual is confused with another of the same name. This is a problem well known in genealogical research circles and a problem that requires careful research to resolve (

Knight 2024). Furthermore, Ceccon noted that Dugdale used a simple shared surname link to establish the legitimate sisters’ relationship, and she concluded that they might not have been sisters at all (

Ceccon 2024, pp. 61–62). The geographical area in which Dugdale was working was an additional factor, as it was one in which local families had intermarried for generations, creating complex relationships that simple surname linkages do not adequately capture. Dugdale’s error was his assumption and the result was a pedigree built on fantasy (

Hatton 2017, p. 8).

Some have expressed concerns that Dugdale did not provide details of his sources or explain his method. His study provides a minimal description of his method of investigation: ‘The sheriff communicated the names of two gentlemen—lifelong residents of the county, one of them 84 years old and for many years town physician—who gave me the genealogies of many of the branches of this family, with details of individual biographies.’ (

Dugdale 1910, pp. 8–9). From this information, Dugdale created a preliminary family tree of 100 people which was then expanded upon. The information in his charts shows prison terms in state and county prisons, and poor-house and outdoor reliefs, suggesting the type of sources he was able to draw on. There can be little doubt that his research was thorough, exhausting all sources available to him. What appears to be missing is an examination of early church records. His chief difficulty must have been the one created by the reliability of memory over time. The people he relied on were able to provide solid evidence for their current understanding of family relationships, but reaching back in time was more difficult without ready access to church records.

Location was a key factor in Dugdale’s analysis as he pondered environment and heredity. Dugdale obscured the location of the Juke family in his publication, introducing it as ‘The ancestral breeding-spot of this family’, one that ‘nestle[d] along the forest-covered margin of five lakes, so rocky as to be at some parts inaccessible’ (

Dugdale 1910, p. 13). This concession to maintain the privacy of the families was for the benefit of the more upstanding members (

Dugdale 1910, p. 1). Ulster County had initially been named in Harris’s account of Margaret and her offspring, given to the New York State Charities Aid Society, and widely publicized (

Commercial Advertiser, 18 March 1875, p. 1). One journalist wrote that ‘In this extraordinary family on the upper Hudson, intermarriage with more vigorous ruffians and country air strengthened the corrupt stock’ (

Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, 20 January 1875, p. 3). The same writer blamed county authorities for failing to provide a foster family for ‘the little neglected waif.’ Another journalist offered a different perspective: ‘For six generations the families had lived in sparsely settled, barren districts in Ulster County and got their livelihood mostly by stealing. The females were prostitutes, and the males roughs and vagabonds. They live together as savages, without any knowledge of purity or modesty, and in the utmost poverty and misery.’ (

Independent Statesman, 7 October 1875, p. 4). Ulster County was uniformly depicted as rural, mountainous, and primitive, offering a physically healthy environment, but lacking the morally uplifting element.

Dugdale was a little less circumspect with the European origins of the family, at least in part. Max, father of two sons who married Juke sisters, was ‘a descendant of the early Dutch settlers, and lived much as the backwoodsmen upon our frontiers now do’ (

Dugdale 1910, p. 14). In terms of the sisters’ genetic origins, he was less descriptive: ‘These six persons belonged to a long lineage, reaching back to the early colonists, and had intermarried so slightly with the emigrant population of the old world that they may be called a strictly American family. They had lived in the same locality for generations, and were so despised by the reputable community that their family name had come to be used generically as a term of reproach.’ (

Dugdale 1910, p. 8). The Dutch origins of the original inhabitants of the New York state area would have been well known, but Dugdale does not emphasize this.

The Dutch influence is evident in that one of the primary organizing institutions in Ulster County was the Dutch Reformed Church. The first church was in Kingston, an important site for the Ulster County community, as for many years it was the only church between New York and Albany. This makes it the source of baptismal and marriage records for residents of all nationalities in the earliest period from its founding in 1660 (

Hoes 1891). The church at Marbletown was the site of many of the Juke family events and dates from 1737. From 1738 to 1749, four congregations in the locality shared the same minister, and in the following period, from 1750 to 1795, three churches employed the same minister (

Zimm 1977).

Despite the usefulness of church records in the present day, Dugdale relied more on the evidence of local witnesses. As he further investigated, he was able to find other women who shared Margaret Robinson’s surname and appeared to share similarly criminal offspring. These became the Juke sisters, the women he identified as Ada, Bell, Clara, Delia, and Effie, as well as an unidentified sixth sister (see

Figure 1). However, as he admitted, Dugdale had not proven that the women were all full sisters. Instead, he concocted a fantasy ‘family’ in a location where relationships were complex.

4. Estabrook’s Jukes

The story of the Jukes was revised for a new generation and with a political purpose that only compounded Dugdale’s errors. It was taken up by the Eugenics Record Office in the early 1910s. Charles Davenport, as the head of the Eugenics Record Office, was active in promoting eugenics as a practical solution to social problems. With influential friends and wealthy associates, he ensured that funds were available for scientific and social research projects. The Eugenics Record Office was able to bend Margaret’s story for their own purposes. Although Dugdale had argued that heredity and environment worked together to produce a criminal family, eugenicists would use Dugdale’s study to argue that heredity was the genesis of the defect and was primarily passed through the female line.

The task of creating this narrative was assigned to Arthur H. Estabrook. A recent graduate of Johns Hopkins University with a doctorate in zoology, he began work at the Eugenics Record Office in 1910. Starting with Dugdale’s work, his research extended the family tree forward another forty years, and followed descendants beyond the county and state borders. There is little doubt that Estabrook’s research was rigorous, since he noted that he had consulted the official records of prisons, sheriffs, charities, alms houses, poor houses, and the two Ulster County judges. His narrative is dense in detail, details of prison sentences, details of charitable aid received, and details of the character of the individuals. The descriptors used by both Dugdale and Estabrook were harsh, even judgmental, to our ears: ‘harlot’, ‘licentious’, ‘inefficient’, ‘pauper’, ‘ignorant’, and Estabrook added ‘mentally defective’. These reflect the eugenic argument that he was making that this family was defective and continued to produce defects in each generation.

Estabrook located the Juke family in a place in a New York county he designated as ‘Z’, writing the following:

Z refers to a city of 20,000 people near the five-lake region where the Jukes lived. Z County is the county in which Z is situated and is the present home of many of the Jukes. Y is a small village in Z County, almost one mile from the lake region.

The rural environment, instead of providing the Arcadian ideal, was seen by eugenicists as primitive, and its inhabitants were ignorant, unable to earn high wages, and lacking in property. They were both backward and inbred. Like other works in the eugenic genre, the Jukes were portrayed as degenerate people living in degenerate hovels in a primitive location (

Smith and Wehmeyer 2012, p. 174).

In elaborating the narrative, Estabrook reused Dugdale’s pseudonym ‘Ada’ for Margaret, the mother of criminals (

Estabrook 1916, p. 2). She had a ‘bastard child, Alexander’, and soon after marrying a laborer, and had ‘four legitimate children’. (

Estabrook 1916, p. 2). ‘Ada’s’ husband was ‘a man who is commonly reputed to be a lineal, although illegitimate, descendant of a Colonial Governor of New York’. (

Estabrook 1916, p. 17). ‘Ada’s’ illegitimate son was born in 1784 and married his first cousin, a daughter of ‘Bell’. According to Estabrook, ‘Alexander’ was not a criminal, he was a laborer, honest, and temperate, as was his wife (

Estabrook 1916, p. 3). It was the next generation in which the defect reemerged, tied back to the promiscuous behavior of ‘Ada’ in falling pregnant before marriage. Estabrook stated ‘Alexander’ and his wife were ‘the ancestors of the distinctly criminal branch of the Juke family.’ (

Estabrook 1916, p. 31). This argument tied a defective genetic inheritance to the female line.

Estabrook made a significant alteration to Dugdale’s findings with respect to the grandchildren of ‘Ada’s’ illegitimate son. Dugdale showed that the eldest son had nine legitimate children on Chart I (

Dugdale 1910, pp. 14–15). In Estabrook’s account, this man had an illegitimate daughter first, the details of which are related to the legitimate second child of Dugdale’s research. Estabrook did not provide any evidence for this change and did not comment on it in his narrative. However, this change provided another example of promiscuity in the family.

‘Bell’, like her sister, seems to have had children before marriage; however, some were of ‘mixed blood.’ Estabrook wrote, she ‘had three children by various negroes. So some negro and, doubtless, some Indian blood became in time disseminated through the whole population of the valley.’ (

Estabrook 1916, p. iii) She is the only sister Estabrook gives an occupation for, a farm laborer and ‘a harlot before marriage’, mother of three ‘mulatto’ children and one ‘white’ child before she married a laborer and ‘revolutionary soldier’ (

Estabrook 1916, p. 28). Both ‘Bell’ and her husband were temperate and ‘not criminal’ (

Estabrook 1916, p. 28). There were four children from this marriage, and ‘Bell’ died in 1832 (

Estabrook 1916, p. 28).

Neither Dugdale nor Estabrook had much information about the other sisters. ‘Clara’ was ‘reputed chaste’ having no children before marriage, but married a man ‘who was licentious and had shot a man’. (

Estabrook 1916, p. 3). ‘Delia’ was apparently a prostitute, and had two illegitimate children and five legitimate children. She was one of the sisters who married a son of ‘Max’. ‘Effie’ was the other woman who married one of ‘Max’s’ sons, ‘who was probably a thief.’ They were the parents of four children. The sixth sister was only mentioned once in passing.

Estabrook had a greater range of resources, with the financial backing of the Eugenics Record Office and the ability to search for family members outside Ulster County and New York State, yet he does not appear to have tried to follow up this sixth sister. Dugdale stated that she had left the county, while Estabrook wrote that one of the six ‘left the country [sic] and nothing is known of her.’ (

Estabrook 1916, p. 2). It is unclear whether there was any further detail in Dugdale’s original notes, but it would seem a significant oversight for Estabrook not to have tried to follow up with the sixth sister.

None of Estabrook’s research shed any further light on the origins of the Juke sisters. Despite this, he was adamant that all ‘six sisters were children of the same mother and four bore the same family name, while the name of two seems to be obscure, and these are for this reason assumed to be illegitimate.’ (

Estabrook 1916, p. 2).

He went into further detail than Dugdale in some respects, as Estabrook supplied birthdates for three of the Juke sisters. Although Dugdale had given a range between 1740 and 1770 which was an extreme range for the children of one woman, Estabrook dated ‘Ada’ between 1755 and 1760, ‘Bell’ about 1760, and ‘Clara’ to 1776, and the implication is that the other sisters were born after these dates (

Estabrook 1916, p. 3). The assumption was that defective genes passed through the female line, yet Estabrook was unable to extend the research back to the mother of the sisters. It should have been her that was the origin of the defect.

A detailed investigation of Estabrook’s narrative demonstrates how the information was altered and interpreted to emphasize both inheritance through the female line and female promiscuity as the cause of genetic defectiveness. His findings were shaped by the agenda of the eugenics movement for political purposes.

5. The Robinson, Sluyter, and Keyser Families

The Juke family was Dugdale’s invention, one reimagined by Estabrook. The story of the Robinson, Sluyter, and Keyser families, on whom this fiction was created, was more complicated. Margaret, the mother of criminals, of Ulster County had become ‘Ada Juke’ in Dugdale’s account. Her real identity, revealed by Scott Christianson, was ‘Margaret Robinson Sloughter’. In the correct period, one Margaret Robinson married Jacob Sluyter.

4 She was the daughter of Isaiah or Jessaia Robinson and his wife Margaret Windfield.

5 She was baptized at Shawangunk on 1 April 1768, without a birth date recorded. Margaret’s mother died aged about 48 in 1786. Margaret’s father, known as Siah, was a soldier during the American Revolution, rising to the rank of Brigadier-General in the Ulster County Militia in the years afterward. His will, written in 1820, was offered for auction and the description stated the following: ‘Siah Robinson was a prominent man in early Ulster County history. He accomplished a great deal in his lifetime and spent much of it in service of his country.’ (

https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/original-1820-last-testament-general-440937826, accessed 11 February 2025). He appears to have remained at Shawangunk, but did not include Margaret in his will.

Margaret must have moved from the family home, as in 1781 she was nearly 23 miles north in Marbletown. She had a child baptized on 23 September 1781 at the Marbletown Dutch Reformed Church, when she must have been in her early teens. His name was William and she was listed as the only parent. The child was probably raised with the assistance of her parents as he retained the Robinson surname. Margaret apparently married Jabob Sluyter, although I could not locate any record. They had more than the four children Dugdale recorded, with baptisms for five well-spaced children found. Some online family trees include up to eight children, but these could not be verified.

To uncover the identities of the Robinson women behind the Juke sister pseudonym required a detailed investigation of Dugdale’s charts, which showed first, second, and third cousin marriages, while exploiting the resources of genealogical websites. Dugdale showed that the illegitimate William Robinson married his first cousin, daughter of ‘Bell’. By 1801, William was the father of a son, John, with Geertje Ploeg. Born in 1786, she was the daughter of Teunis Ploeg and his wife Geertje Robinson. This union between William and Geertje reveals the identity of Geertje Robinson. It is possible that she was Margaret’s sister, although Margaret’s is the only baptism found for any child of her parents. Another, more likely, possibility is that she was the daughter of another couple, William Robinson and his wife Maria Sluyter. This girl was baptized in Kingston in August 1752.

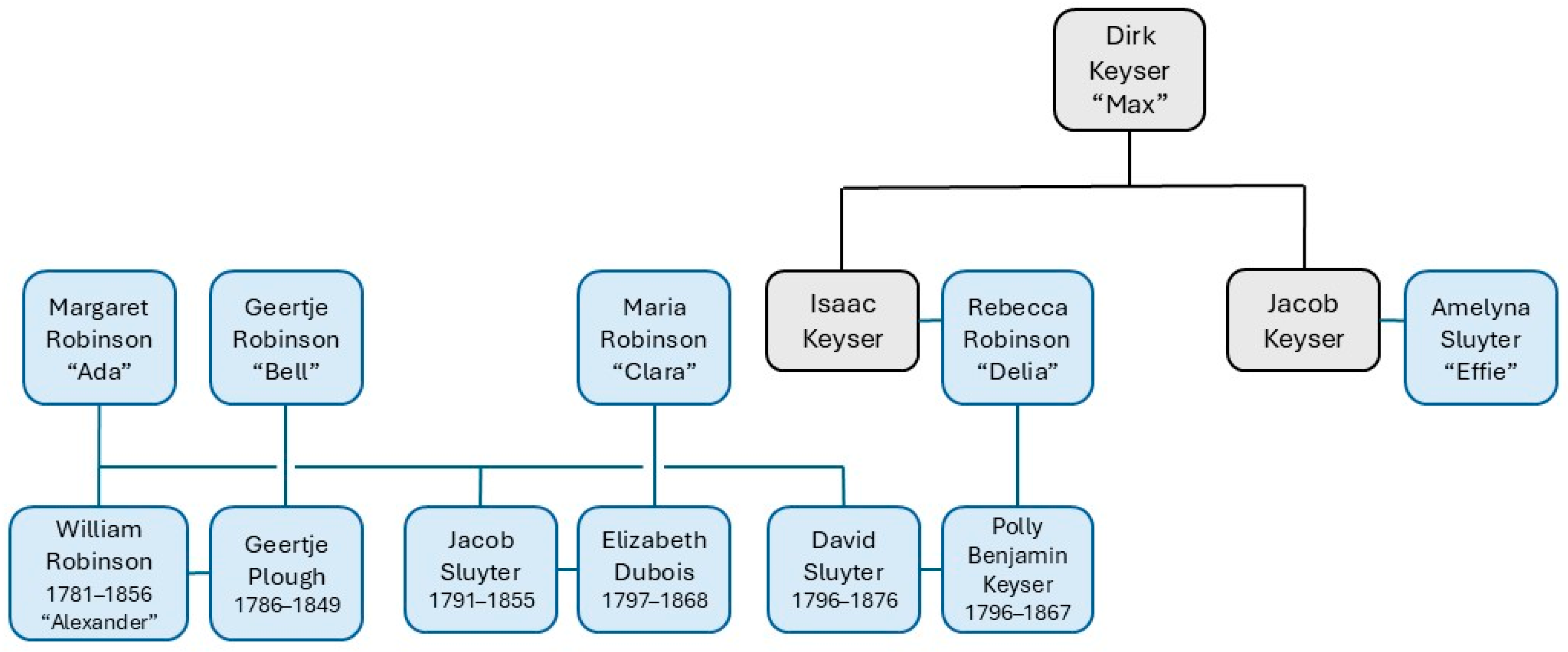

A similar deduction can be made about the identities of ‘Clara’ and ‘Delia’, given that Dugdale identified their daughters as marrying into the legitimate family of Margaret. Thus, Margaret’s son Jacob Sluyter married Elizabeth Dubois, the daughter of Maria Robinson and her husband Samuel. Another son, David Sluyter, married Polly Benjamin Keyser, the daughter of Rebecca Robinson and her husband, Isaac Keyser. These relationships are shown in

Figure 2. The baptism records show that Maria and Rebecca were daughters of William Robinson and Maria Sluyter, making it possible that Geertje was their sister, rather than Margaret’s. William and Maria had married in Kingston in 1849. Their second daughter, Cornelia, born in 1754, married Willem Wiler or Wheeler. The lack of information currently able to be found about her family means that she could be the missing one of Dugdale’s Juke sisters.

The fifth sister was more difficult to identify. Dugdale’s narrative had ‘Effie’ married to one of ‘Max’s’ sons, therefore, it appears likely that the union would be between a Keyser son and a woman with a surname other than Robinson, but one that could appear to be an illegitimate sister. It was likely that the surname would be Windfield, like Margaret’s mother, or Sluyter, like Maria and Rebecca’s mother. The person most likely to be Dugdale’s ‘Max’ is Dirk Keyser who was born in Stone Ridge, one mile from Marbletown in 1710. He and his wife Sara De Lang appear to have had four sons and four daughters. In addition to the marriage ties to the Robinson and Sluyter families, his other children married Davis, Personius, Muller, and Shoudy spouses. In 1771, Dirk and Sara’s son Jacob Keyser married Amelyna or Amelia Sluyter in Kingston. If the Juke sisters were thought to be the daughters of Maria Sluyter, with the majority the product of her union with William Robinson, then Dugdale might have assumed that Amelyna Sluyter was an illegitimate child of Maria. In the present, her uncommon first name means that she was easily found on genealogical websites to be the daughter of Jacob Sluyter and his wife Lydia Keyser, with a baptismal record in nearby New Paltz in 1750. The union of Amelyna and Jacob Keyser produced not four children, as Dugdale and Estabrook noted, but four sons and three daughters.

6. Layers of Complexity and Prejudices

For Dugdale, consanguinity was one of the features of the Juke family (

Dugdale 1910, p. 13). He drew a tentative conclusion that ‘Pauperism preponderates in the consanguineous lines’. (

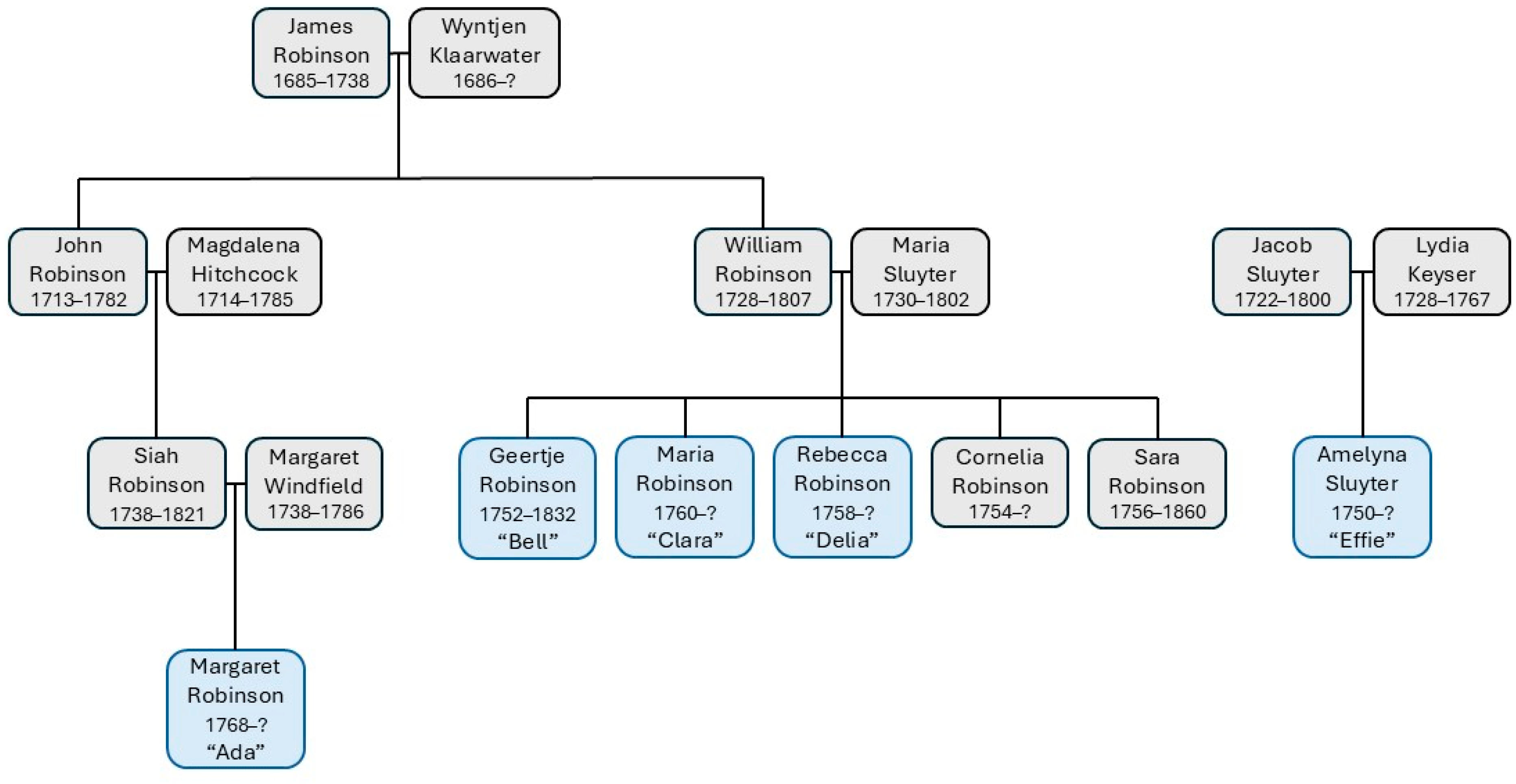

Dugdale 1910, p. 16). Cousin marriages were common in Ulster County, and it is obvious from my description of the women’s identities that there were numerous links between families with the Robinson, Keyser, and Sluyter surnames. Marbletown church records date from 1746, and one of the baptisms from that year was for Nicolaas, son of Nicolaas Sluiter and Jannetje Keiser. (Family Search, Marbletown Church Records 1746–1871, Film #007903303). As shown in

Figure 3, the investigation of the baptismal records shows that Geertje (‘Bell’), Maria (‘Clara’), and Rebecca (‘Delia’) Robinson were first cousins of Margaret’s father, Siah Robinson. The relationship between Amelyna’s (‘Effie’) father, Jacob Sluyter, and Margaret’s husband, another Jacob Sluyter, is more difficult to tease out. However, they were not father and son.

Much of Dugdale and Estabrook’s Juke family research is based on the production of illegitimate children by the sisters. Even now, these children are particularly difficult to investigate, as it is conceivable that such children may not have been baptized, which is the only record available to confirm a birth for this time. We might note that the morals of the late eighteenth century were being judged by researchers in the late nineteenth century, reevaluated in the early twentieth, and now being reassessed in the early twenty-first. According to Daniel Scott Smith and Michael S. Hindus, later eighteenth-century America experienced a peak of about 30 percent for premarital pregnancies (

Smith and Hindus 1975, p. 537). Such pregnancies were measured by locating conceptions that occurred before the marriage of the first postmaritally born child. This suggests that premarital sex was not uncommon at the time.

In contrast to Estabrook’s assertions and the implication in Dugdale’s study, Margaret (‘Ada’) was not the eldest of the Juke ‘sisters’. Instead, Amelyna (‘Effie’) was the eldest of the women identified as the Juke sisters, born in 1750, while Geertje (‘Bell’) was most likely born in 1752, Rebecca (‘Delia’) in 1758, and Maria (‘Clara’) in 1760. Margaret (‘Ada’) was the youngest, being baptized in 1768. Although Dugdale had some excuse for his focus on Margaret as ‘Ada’, as she was his chief progenitor, Estabrook further amplified that she was the oldest of the ‘sisters’. Eugenic studies tended to use data in ways that served their purposes; therefore, it is not surprising that Estabrook appeared to strengthen the study by adding dates for the sisters. This implies that he had found an additional source of information, yet the dates he gave appear without foundation.

This article has found that Margaret was quite likely only thirteen when her son was born.

6 In Dugdale’s era, the 1870s, this was not considered evidence of possible sexual assault but of her personal immorality. Forty years later, the families associated with the Jukes were described as producing ‘girls and young women …very comely in appearance and loose in morals.’ (

Estabrook 1916, p. 2). Estabrook suggests that ‘immorality’ was entirely the fault of those he describes as desirable young women. We can also note that Estabrook’s reworking ages Margaret or ‘Ada’ and emphasizes her as the eldest Juke sister. To achieve this, he placed her birth between 1755 and 1760. As a result, her illegitimate son, who both Dugdale and Estabrook incorrectly dated as being born in 1784, was born when she was between 24 and 29 years old. Instead of being a young teenager, ‘Ada’ is a mature woman, thus a narrative was created with more blame placed on her than might have been the case.

Another troubling aspect of Estabrook’s reworking is also date-related. Although Dugdale did not give dates for ‘Bell Juke’, merely stating she died in 1832, Estabrook had her born about 1760. This creates a conflict with the calculated dates of her eldest illegitimate son. Dugdale described him as dying aged 60 in about 1820, and thus born about 1760 (

Dugdale 1910, pp. 64–65). Estabrook copies Dugdale’s 1820 date but ignores the age at death, perhaps recognizing that it is impossible that the dates he had given could be correct if Dugdale’s information was correct. The real ‘Bell’, Geertje Robinson, was most likely born in 1752 and therefore could not have had children before about 1765. It appears that either Geertje was not the mother of at least some of the attributed illegitimate children or their date details were given incorrectly. This points to the fallibility of the original data. Unfortunately, this is one of the areas this researcher was unable to investigate without the original code books, as no illegitimate children were baptized with Geertje Robinson as their mother.

Those who investigated problematic families, such as Dugdale and Estabrook, collected instances of undesirable behavior. Every event in which an individual needed help or violated social norms was counted against him or her. As such, the lack of records in the early years, when there was no alms house or other organized charity for the needy, must have restricted the cataloging of objectionable actions. During the time being researched, both men and women took advantage of out-relief from charitable aid societies when in serious need and occasionally had to resort to entering the poor house. The original researchers did not account for the effect of the economy on these Ulster Counties. There was no allowance made for accident, injury, or illness in the social condemnation of the pauper. The pauper was regarded as an individual moral failure, rather than a victim of economic circumstances. Even those in military service seem to have been seen negatively. Many of the men on Dugdale’s charts were noted as soldiers, some even collecting pensions. Instead of attracting admiration for their contribution, attitudes perhaps reflect an antimilitary view in the wake of the civil war.

The mixing of the bad blood of the Juke family with that of other ‘better’ families was noted in both Dugdale and Estabrook’s accounts. One example was one of Margaret’s granddaughters, Ann, who cohabited with a man named Joseph Delamater. Dugdale records him as a mason, an excellent workman but a thief and drunkard; a man who had deserted his wife to live with Ann. Joseph’s father came from a good family and was well off, but his brother had swindled him out of his property. This suggests descent from a fairly respectable but possibly criminal family. However, with their focus on transmission through the female line, both Dugdale and Estabrook ignore the potential of a male criminal element in a ‘better’ family.

The political agenda of eugenics overrode developing scientific knowledge of genetics and ignored the poor quality of the original data. This has been observed in reevaluations of other family studies. David Smith and Michael Wehmeyer revealed not only inaccuracies in the Kallikak study, but similar fundamental errors in identification. Nathaniel Deutsch found that the Tribe of Ismael origin family had a normal family history, but when reworked by authors with a particular agenda, the study was used to make racial arguments. Elof Axel Carlson has defended Dugdale’s Juke study as presenting an environmental interpretation rather than the hereditary view that the eugenicists preferred. However, the eugenic argument was strongly made by Estabrook and widely publicized. Both Dugdale and Estabrook conducted extensive research and were thorough in their investigations, particularly in sources in their own time periods. This was then interpreted in ways that advanced their arguments. Therefore, their conclusions reflected their personal beliefs and were based on unsubstantiated assumptions about relationships.

7. Conclusions

The aim of this article is to examine the real people behind the fictional personas created by Dugdale and extrapolated by Estabrook in their studies of the Juke family. It is important to look at the real identities of people anonymized in their narratives. Only by doing so can we see the errors and biases of the original researchers and challenge the simplified account of the inherited defect that was reimagined as an inevitable and inescapable outcome. Dugdale produced a false pedigree based on false assumptions. The field research seems to have produced accurate results, despite the obvious predisposition to find unfavorable outcomes. We might also note the irony that Margaret, the mother of criminals, did not have any criminal sons or daughters. Instead, it was among her grandchildren and great grandchildren that some had encounters with the law. It was an irony that neither researcher commented on. Both Dugdale and Estabrook found what they were looking for: instances of need in times of deprivation, of illness, and of crime. They were both good researchers who communicated their results in ways that reflected their belief systems and appealed to the wider public. They produced a simple narrative that does not capture the complexities or attempt to explain them, merely to provide a rallying cry and, by the early twentieth century, to promote a moral panic.

The analysis of the Juke family research carried out here has extended our knowledge of the flawed assumptions hidden in eugenic studies. Writing before the popularity of eugenics, Dugdale attempted to evaluate the importance of heredity and the environment on life outcomes, while Estabrook used the resources of the eugenic movement to focus on evidence of inheritable defects. Failure to establish the identity of the parents undermines some of their deductions. For example, Margaret was found to be the daughter of a respectable couple. Locating the identities of the real ‘sisters’ shows that Dugdale made incorrect connections, some of the sisters had more distant relationships, and other relationships cannot be proven. This current study had several limitations, including the inability to use the original code book. The current reexamination is only possible by using the information found in the charts Dugdale included in his book, alongside the information in the public domain that ‘Ada Juke’ was Margaret Robinson Sloughter. Another limitation has been that I have used online family trees, which we must acknowledge are not necessarily accurate, complete, or linked to primary sources. However, they do provide valuable clues that can be verified in primary sources.

The findings presented here suggest that further research into Dugdale’s charts is possible. Furthermore, future researchers might find it profitable to challenge the privacy restrictions currently in place. In the case of the Juke family, a family was created when overly simplistic identifications were relied upon. The errors were compounded in subsequent studies, undermining the pretense that Estabrook’s was a serious scientific investigation into genetics. In that vein, future researchers may be able to utilize DNA to refute some of the erroneous assumptions.